What do you think?

Rate this book

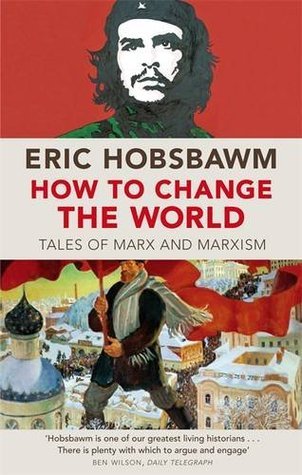

480 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2011

We cannot foresee the solutions of the problems facing the world in the twenty-first century, but if they are to have a chance of success they must ask Marx's questions, even if they do not wish to accept his various disciples' answers.

A generation of intellectuals came to Marxism in and mainly through the slump and the struggle against fascism, in times of falling darkness. Those who survived have oftend been disappointed. They have delved into their past to discover whether they were mistaken, what their errors might have been or what went wrong with their high hopes. Many have ceased to be Marxists. But it is safe to say that very few, if any of them, reject their participation in the fight against and defeat of fascism.

Then, after the 1970s, everything changed : both Lenin and Bernstein lost their hopes {ie, both revolution and reform}. Everyone knows that the Soviet system collapsed, while the non-state communist parties faded. What is less familiar is that Bernsteinian social democracy was also swept away.

The Iranian revolution of 1979 was the first major revolution since Cromwell's time that was not inspired by a secular ideology but appealed to the masses in the language of religion

The state and other public authorities remain the only institutions capable of distributing the social product among its people, in human terms, and to meet human needs that cannot be satisfied by the market. Politics therefore has remained and remains a necessary struggle for social improvement. Indeed, the great economic crisis that began in 2008 as a sort of right-wing equivalent to the fall of the Berlin Wall brought an immediate realisation that the state was essential to an economy in trouble, as it had been essential to the triumph of neo-liberalism when governments had laid its foundations by systematic privatisation and deregulation.