What do you think?

Rate this book

Leather Bound

First published January 1, 2011

Ah, but as economists and Friedman and Mandelbaum in this book say: "this time it's different." Sure, the U.S.'s China envy over their manufacturing prowess, explosive economic growth and increasing influence has morphed into study of China's management and educational practices (Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother) just like before. Sure, U.S. business students minor in Mandarin just like they use to study Japanese back then. Sure, China's near double-digit sustained GDP growth threatens to make it the world's premiere place to do business just as Japan's did in the late 80's. And sure, the U.S. worries about reliance on continuing Chinese investments to pull the economy out of its doldrums just as it looked to the east during the '90 to '92 recession. However, this time it's different.

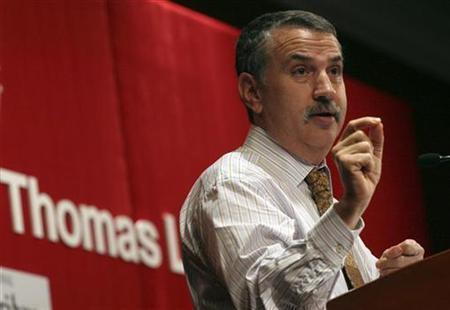

Friedman and Mandelbaum may indeed have a point. Get passed some of the hand-wringing about broken escalators and aging airports and the pair do present worrisome trends in declining educational investments and, particularly, a political system that does very much resemble World Wrestling Federation more than the impassioned but respectful debate Washington, Jefferson, Adams and the other founding fathers used to get the place started. The authors, New York Time political commentators by trade, are most in their element when talking about this political system and their best points grow out of the admission that the 24/7 news cycle created to cover the 9-11 attacks are massively counter-productive when reporting on nuanced matters of public policy. On this poisoned ground, nothing much is going to grow and some cause for concern over continued American single-superpower-dom is credible.

Friedman and Mandelbaum tie many of their solutions to the old bug-a-boo of recasting the U.S. educational system. They cite the old familiar world rankings showing the U.S. trailing Latvia in math and they point east to the educational prowess of Chinese and other Asian-country students in comparison. The authors miss some cultural context in their prescription. As Dennis Miller pointed out in his rants from early 90's, America was never what you would call highbrow. Eastern education practices work well partially because their basic culture holds education in high-esteem. In the U.S. being called an "Einstein" is not necessarily a compliment. Thus putting all of the eggs in the education basket may not be "...how we come back" as the subtitle puts it.

As NY Times writers, little complaint can be made of the book's style. As foreign policy wonks, however, complaint can be made of a fair amount of digressiveness, arcania and, frankly, droning on. The book contains some unnecessarily filler; the most humorous example is the recitation of nearly all the lyrics from T Bone Burnett's Fallin' and Flyin'. It's a good song but does a political book really need a musical interlude? The authors adopt the hugely irritating habit normally reserved for business books of consultant-ese. We learn about "Creative Creators", and how they differ from "Creative Servers" in a spiral of consultant speak that culminates in the revelation that "Uncreative Creators" actually exist. Also borrowed from the latest Franklin-Covey publication is practice of holding up the behavior of a single once-in-a-generation success as a model. In this case the boys talk about how(has he been officially sainted yet?) Steve Jobs dropped out of Reed College, studied calligraphy and parlayed these experiences to build a half-trillion dollar company. Better practical career advance you are unlikely to receive.

In short, the old democrats are right to despair that the American empire may be following the natural arc that diminished the British empire and took out the Romans, Macedonians and Egyptians before her. Whether solutions can be found east of Mongolia and west of Formosia is to be determined.

We want [America] to be the place where innovators and entrepreneurs the world over come to locate all or part of their operations because our workforce is so productive; our infrastructure and Internet bandwidth are so advanced; our openness to talent from anywhere is second to none; our funding for basic research is so generous; our rule of law, patent protection, and investment- and manufacturing-friendly tax code is superior to what can be found in any other country; and our openness to collaboration is unparalleled--all because we have updated and expanded our formula for success. We want America to be the place where people dream something, design something, start something, collaborate with others on something, and manufacture something--in an age in which every link in that chain can now be added in so many places. (p. 335)