What do you think?

Rate this book

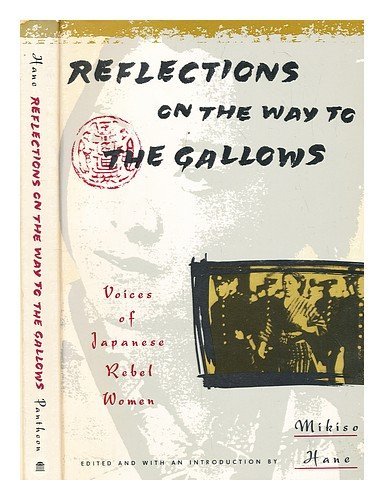

274 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1988

"During that time, we were all under the impression that we would get promoted if we killed some socialists. I almost got myself in trouble."Disclaimer: if my writing seems somewhat wired in this review, I just got an especially sugary boba drink after a participating in a rather exacting interview. So, there you have it.

-A would be assassin of Yamakawa Kikue, realist social critic, communist, and women's rights advocate

"I was afraid that the supporters of the emperor and champions of patriotism might dig up my corpse and hack it to bits. I did not want to look too shabby when this happened."P.S. The more I read about anarchist/communist/socialist work outside of the US/Europe, the more I'm rather fed up with how little attention Emma Goldman paid to such in her autobiography, but that doesn't mean I can't make use of her material when it is highly appropriate to do so.

-Kanno Sugako, written six days before she was executed for plotting to assassinate the emperor

[T]here had never been an ideal, however humane and peaceful, which in its time had been considered "within the law."