What do you think?

Rate this book

464 pages, Hardcover

First published December 27, 2012

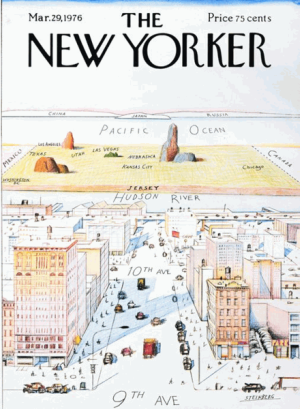

“The parody has been parodied many times, but the best modern parallel, and certainly the rudest, is to be found in the work of the much travelled Bulgarian graphic designer Yanko Tsvetkov. Tsvetkov, who works under the name Alphadesigner, may well have constructed the most offensive and cynical atlas in the world, all of it stereotypical, some of it funny. His Mercator projection entitled The World According to Americans showed a Russia labelled simply ‘Commies’, and a Canada labelled ‘Vegetarians’. He has also produced the Ultimate Bigot’s Supersize Calendar of the World, which includes Europe According to the Greeks. In this one, the bulk of European citizens live in the ‘Union of Stingy Workaholics’, while the UK is categorised as ‘George Michael’.”

BOTW

BOTW