What do you think?

Rate this book

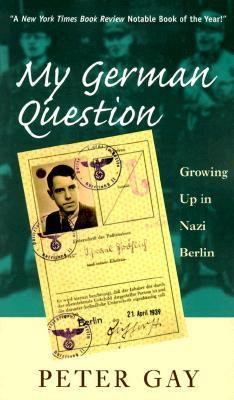

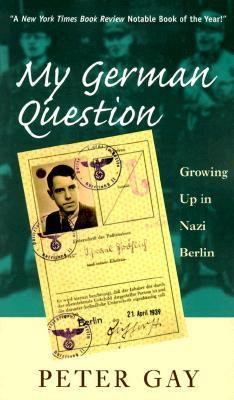

224 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1998

Much of this record was enriched and elaborated to the world in the war crimes trials of Nürnberg, launched soon after the surrender of the Germans. Some of the verdicts were hard to understand: Franz von Papen, who more than any politician in the dying Weimar Republic had maneuvered Hitler into power, was acquitted. Others received more appropriate sentences; Goring cheated the executioner by taking poison, but Joachim von Ribbentrop, the former champagne salesman risen to foreign minister; Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Hitler’s man in the armed forces; Alfred Rosenberg, the party’s most influential racial theorist; Hans Frank, who governed occupied Poland with exemplary brutality; Wilhelm Frick, one of Hitler’s most devoted supporters and, as minister of the interior, responsible for enforcing the racial laws; Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the Austrian Nazi who managed his country’s Anschluss to Germany and distinguished himself in his own way as governor of the occupied Netherlands; Ernst Kaltenbrunner, another Austrian who rose to high posts in “internal security”; General Alfred Jodl, one of Hitler’s closest advisers; Fritz Sauckel, who after a long career in the party was responsible for slave labor; and last but by no means least, Julius Streicher—I have mentioned him before but I don’t mind mentioning him again in this context—were hanged. All this gave me much satisfaction then, as it gives me satisfaction now to type these names. I visualized, and visualize, the noose tightening, tightening. Other leading Nazis were condemned to death in later trials, and the Russians, with few legal scruples to delay them, proved exceptionally efficient if not always very discriminating.