What do you think?

Rate this book

227 pages, Paperback

First published April 15, 2012

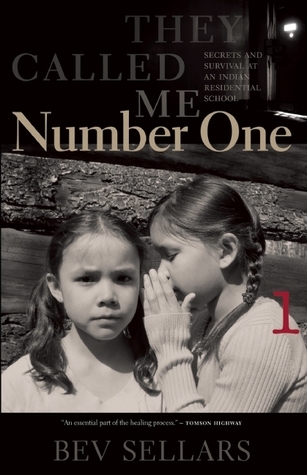

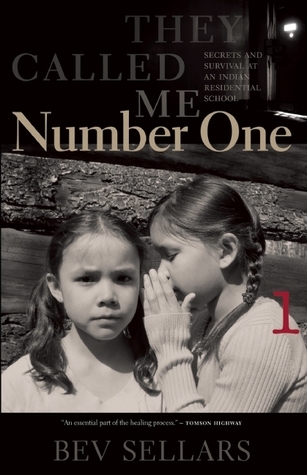

Another thing that happened soon after we arrived at residential school is that we were given a number that would become our identity throughout our years at school. I became Number 1 on the girls' side. Although the other kids all continued to call me by name, "Bev Sellars" ceased to exist for most of the nuns and priests. Instead they would say, "Number 1, come here" or "I want these girls in my office, Numbers 3, 14, 72, and 105" or "Number 1, say the second decade of the rosary". Ninety or more years after she left St. Joseph's Mission, my grandmother still remembered her number - 27 - and - 28 - the number assigned to her sister Annie. My mom remembers her number was 71.

It was normal to find out that community members were serving time in jail. The funny thing was that no one ever asked, "What crime did he or she commit?" Guilt or innocence was irrelevant because, if an Indian was accused of a crime, they pleaded guilty just like at the Mission. The residential schools taught us to take our punishment even if we were innocent. The schools taught us that we had no rights and that trying to complain or reveal the truth only made things worse. We learned not to complain. We learned that no one cared whether we were innocent or guilty. We learned that we were totally at the mercy of White authority.

When I grew up, if anyone asked me about my childhood I would always say, "I had a great childhood." This probably surprised some people who knew of my history at residential school but, when I thought of my childhood, I only included my life at Deep Creek and Soda Creek. I did not want others to know about my years at the Mission. Those lazy, carefree days of summer were my childhood until I was reminded of the other childhood I didn't want to tell anyone about.