What do you think?

Rate this book

611 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1558

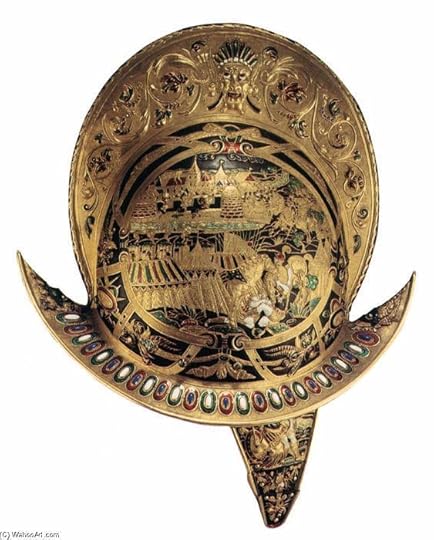

LIFE AMONGST METALS

.. Without further provocation he retorted that I was a donkey; whereupon I said that he was not speaking the truth; that I was a better man than he in every respect, but that if he kept on irritating me I would give him harder kicks than any donkey could.

All men of whatsoever quality they be, who have done anything of excellence, or which may properly resemble excellence, ought, if they be persons of truth and honesty, to describe their life with their own hand

I drew a little dagger with a sharpened edge, and breaking the line of his defenders, laid my hand upon his breast so quickly and coolly, that none of them were able to prevent me. Then I aimed to strike him in the face; but fright made him turn his head round; and I stabbed him just beneath the ear. I only gave two blows, for he fell stone dead by the second. I had not meant to kill him; but as the saying goes, knocks are not dealt by measure.