What do you think?

Rate this book

256 pages, Hardcover

First published September 9, 2021

‘The front door and windows rattle. Maybe it isn’t the wind. Maybe someone’s actually there. Maybe they’ve come to drag out whoever’s inside. To slash and burn To fit with target vests and tie up against trees. Against that black tree as it brandishes its saw-blade arms.’

‘I wanted to ask what it is that makes human beings harm others so brutally, and how we ought to understand those who never lose hold of their humanity in the face of violence.’

‘Images of suffering can arouse our horror, simulating an illusive identification between us and the victim or “a fantasy of witness” before we are conveniently deposited back into our lives so that someone else’s trauma becomes our personalized catharsis.’

‘Rather than an act of rememberance, the recitation of “Death Fugue” turned into a mantra to ward off difficult engagement with the past. But this is how it is when a poem becomes commemorative. It becomes all pious gesture and drained of meaning. When a poem becomes commemorative, it dies.’

I remembered... everyone who's ever suffered similar fates regardless of place...

Hit with bullets.

Hit with cudgels.

Lives severed by blades.

How agonizing it must have been

”Después de una década de llevarlos en silencio en nuestros corazones, pronto llegará el día en el que los deudos de las víctimas podamos reencontrarnos con nuestros añorados difuntos y estos alcancen por fin el descanso eterno”

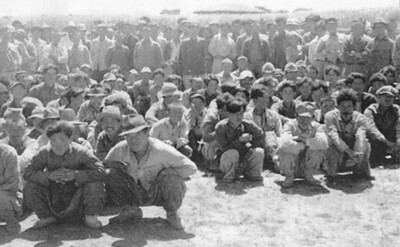

“No es casualidad que aquel invierno fueran asesinadas treinta mil personas en esta isla, y en el verano del año siguiente, otras doscientas mil en el resto del país. El gobierno militar estadounidense ordenó poner fin al comunismo a toda costa, masacrando de ser preciso a los trescientos mil habitantes que componían por aquel entonces la población de Jeju… No solo se autorizó, sino que se recompensó la atrocidad de disparar a los bebés en la cabeza, lo que hizo que ascendieran a mil quinientos los niños menores de diez amos muertos por heridas de bala”

“Esas pesadillas me robaron la vida. No dejaron que quedara a mi lado ni un solo ser vivo”

“… un cuerpo despojado de su caparazón que se arrastra despacio como una babosa sobre el filo de un cuchillo. Un cuerpo que desea vivir. Un cuerpo hendido y cortado. Un cuerpo que se escabulle, se abraza y se aferra. Un cuerpo que se arrodilla. Un cuerpo que ruega. Un cuerpo del que no para de supurar algo como sangre, pus o lágrimas”

‘That is how death avoided me. Like an asteroid thought to be on a collision course avoids Earth by a hair’s breadth, hurtling past at a furious velocity that knows neither regret nor hesitation. I had not reconciled with life, but I had to resume living.’

‘It was early November and the tall maple trees were ablaze and glimmering in the sunlight. Beauty—but the wiring inside me that would sense beauty was dead or failing. One morning, the first frost of the season covered the half-frozen earth—Brittle autumn leaves as big as young faces tumbled past me, and the limbs of the suddenly denuded plane trees, as their Korean name of buhzeum—flaking skin—suggests, resembled grey-white flesh stripped raw.’

‘—in the areas where the conifers and subtropical broadleaf trees grew together, the wind created an indescribable harmony as it passed through the branches and leaves, its speed and rhythm varying by the type of tree. Sunlight reflected off the lustrous camellia leaves, whose angles shifted from moment to moment. Vines of maple-leaf mountain yam wound around the cryptomeria trunks and climbed them to distant heights, swaying like swing ropes.’

‘Since that evening, Inseon and I have been friends. We went through all our life milestones together, right up until she moved back to the island—messaging me at odd moments to tell me she was dropping by. Just do one thing for me? Let me in. And when I did, she would bring her arms around my shoulders, along with a rush of cold wind and the smell of cigarettes—It feels as though invisible snowflakes fill the space between us. As though the words we’ve swallowed are being sealed in between their myriad melded arms.’

‘On the black screen, sporadic points of radiance appeared like ghosts and briefly shimmered: flashes emitted by distant ocean creatures. Occasionally these bioluminescent organisms came into full view on camera, only to emerge back into obscurity. The vertical stretch of sea where the points of light gleamed grew increasingly short. The solid opaque expanse that intersected with it grew overwhelmingly vast. After a while I wondered if the dark was all that remained, but then the camera captured the translucent glow of a giant phantom jellyfish amid what looked like.'

‘—pine-nut juk—I took my time with the unduly hot bowl of rice porridge—people walked past the window in bodies that looked fragile enough to shatter. Life was exceedingly vulnerable, I realised. The flesh, organs, bones, breaths passing before my eyes all held within them the potential to snap, to cease—.’

‘The twilight pouring into the woods—darkness grew, the more vividly the vents in the wood-burning stove glowed red. I don’t know why he hid his illness from me—Inseon started at the bright holes, as if staring hard enough at those gleaming eyes would make words flow out of the stove like molten iron.

We haven’t parted ways, not yet.’