What do you think?

Rate this book

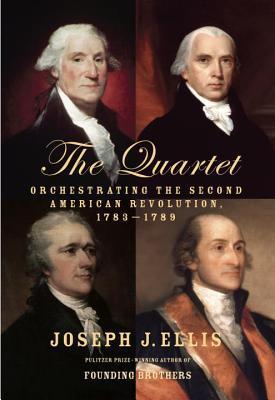

320 pages, Hardcover

First published May 5, 2015

I confess that I do not entirely approve this constitution at present, but sir, I am not sure that I shall never approve it: For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged, by better information or by fuller consideration, to change opinions on important subjects, which I once felt right, but found to be otherwise.In summary, Joseph Ellis contends that the 1776 Revolution did not create a nation or a republic, something that was not in fact fully achieved until 1865 and that a quartet of 4 prominent political figures in 1787-88 set an agenda for intended nationhood vs. the individual "nation states" as envisioned with the original Articles of Confederation. Also, the American Constitution would never have been approved had slavery been outlawed.

It is therefore that the older I grow the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others. I doubt too whether any other convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better constitution. Thus I consent sir, to this constitution because I expect no better and am not sure that it is not the best.