What do you think?

Rate this book

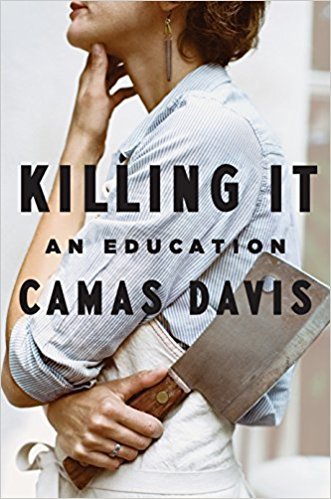

352 pages, Hardcover

First published July 24, 2018

A lot of people, a lot of our listeners, including meat eaters, will be revolted by the idea that you wanted to study butchery and that you teach it to students as part of what you teach them. Explain why you want people to know more about not only the provenance of their meat but also how it's butchered.

I wrote the book to explore where that revulsion comes from and what purpose it serves. In the process of going to France and learning how to turn an animal into food, I had to really confront my own moments of cringing or turning away or not wanting to see or know. And I came to think over time about how that might support our current system of meat production and consumption, how being revolted is a way to make us feel we don't have responsibility or we're not a part of that system, and so, therefore, either there's nothing we can do, or we just allow that system to continue unchecked.

In my own education, I've found the more I went into those processes - be it slaughter or whole-animal butchery or turning a pig head into pate de tete - the more I thought - more deeply I thought about why I eat meat, how much of it I eat, where it comes from, and the more I was able to assess how comfortable I felt with certain parts of those production methods and which kinds of production methods felt right and which felt wrong - and so it's my theory - or it's a theory that I've developed over time through my own education - that the further in we go, the better choices we make and the more agency we have in changing that system that brings food to our table.

There are a lot of books out there — and documentaries and articles and every form of content you can think of — explaining all the problems with animal farming, whether that’s environmental or animal or health or workers’ rights. We’ve got that down, I think, as a society. I think people don’t internalize the information, but at least it’s out there.

What we don’t have as much about is how we get to the solution. Psychologically, I think that’s a really important part of how people understand the problem and kind of take it to heart and see it as an important movement. You know they need to see a path forward, not just a gaping problem.

People have what psychologists call a collapse of compassion when they see an insurmountable problem — a million deaths is a statistic; a single death is a tragedy. And they don’t appreciate that scale because they don’t see a concrete possibility. How do we actually go about solving this? I was able to look from a perspective of psychology, sociology, history, economics, etc., and really ask, How do we pave the path forward? …

[C]ollapse of compassion … is the apathy that happens when we see a large problem that doesn’t have a clear solution. If people choose to feel compassion and feel empathy toward farmed animals, it’s a pretty significant commitment because then they start to recognize what a moral atrocity animal farming is. And if they don’t see that that problem can be solved, then at some level, I think they understand that they’re going to be stuck in this cycle of sadness, of anger, of whatever negative emotions they feel about the issue.

An emissions cut of a couple of percentage points is nothing to sneer at, but it is certainly not what will ‘save the planet’. The inconvenient truth is that few individual actions can transform the battle against climate change. One action that could make a genuine difference is campaigning for far more spending on global investment in green-energy research and development. This technology needs to be massively developed if we are ever to bring forward the day when alternatives can outcompete fossil fuels.

More R&D also is needed to reduce the carbon impact of farming, as well as to develop and produce at scale artificial meat, which could cut greenhouse-gas emissions by up to 96%, relative to conventionally produced meat.