What do you think?

Rate this book

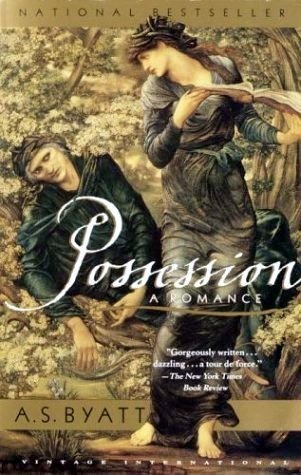

555 pages, Paperback

First published September 1, 1990

Gloves lie together

Limp and calm

Finger to finger

Palm to palm

With whitest tissue

To embalm

In these quiet cases

White hands creep

With supple stretchings

Out of sleep

Fingers clasp fingers

Troth to kee

- C. LaMotte

“Siento que esto me tiene dominada. Quiero saber qué pasó, y quiero ser yo quien lo averigüe… No es codicia profesional. Es algo más primitivo”

“… las palabras son toda mi vida, toda mi vida; es una necesidad como la de la Araña que lleva delante un enorme Fardo de Seda que tiene que ir hilando: la seda es su vida, su casa, su seguridad, su comida y su bebida; y si se la atacan o se la deshacen, qué otra cosa puede hacer sino fabricar más, hilar de nuevo, diseñar otra vez. Dirá usted que es paciente, y lo es; puede que también sea salvaje; es su naturaleza, tiene que hacerlo o morirse de empacho, ¿me comprende?”

“Sabemos que nos empuja el deseo, pero no lo podemos ver como lo veían ellos, ¿no es cierto? Nosotros no pronunciamos nunca la palabra Amor; sabemos que es un constructo ideológico sospechoso, sobre todo el Amor Romántico; así que tenemos que hacer un verdadero esfuerzo de imaginación para sentir lo que sentirían ellos, aquí, creyendo en esas cosas..., en el Amor..., en sí mismos..., creyendo que lo que hacían era importante"

“La verdad es, mi querida señorita LaMotte, que vivimos en un mundo viejo: un mundo cansado, un mundo que ha ido apilando especulaciones y observaciones hasta que verdades que habrían podido ser aprehensibles al sol primaveral de la mañana de los hombres, por el joven Plotino o el extático Juan de Patmos, ahora están oscurecidas por palimpsesto sobre palimpsesto, por excrecencias córneas y espesas sobre esa clara visión; como la serpiente que muda, antes de irrumpir con su nueva piel flexible y brillante, se encuentra cegada por las costras de la antigua; o, podríamos decir, como las bellas líneas de fe que se alzaban en las animosas torres de las antiguas catedrales y abadías son a la vez roídas por el tiempo y la suciedad y blandamente amortajadas por las negras acreciones de nuestras ciudades industriales, nuestra riqueza, nuestros descubrimientos mismos, nuestro Progreso”

“ya que hemos llegado al final feliz, no hay para qué seguir”