What do you think?

Rate this book

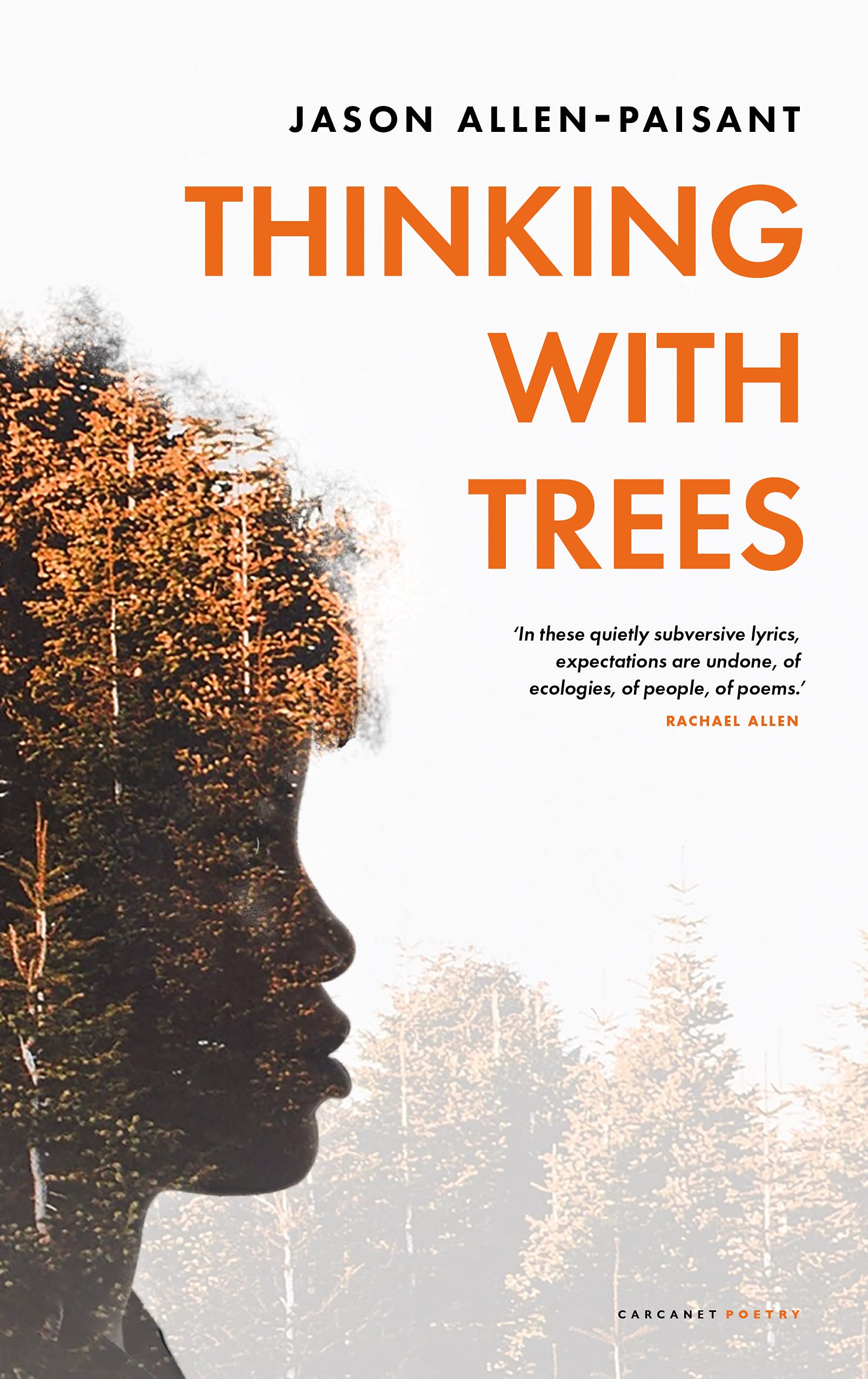

128 pages, Paperback

First published June 24, 2021

In Porus life was un-

pastoral

The woodland was there

not for living in going for walks

or thinking

Trees were answers to our needs

not objects of desire

woodfire

beware of spring

believe you are

a sprout of grass

and love all you see

but come out of the woods

before the white boys

with pitbulls

come