What do you think?

Rate this book

153 pages, Paperback

First published May 1, 1965

At one time, according to Sir George H. Darwin, the Moon was very close to the Earth. Then the tides gradually pushed her far away: the tides that the Moon herself causes in the Earth's waters, where the Earth slowly loses energy.And in the next page:

How well I know! -- old Qfwfq cried,-- the rest of you can't remember, but I can. We had her on top of us all the time, that enormous Moon: when she was full -- nights as bright as day, but with a butter-colored light -- it looked as if she were going to crush us...

There were nights when the Moon was full and very, very low, and the tide was so high that the Moon missed a ducking in the sea by a hair's-breadth; well, let's say a few yards anyway. Climb up on the Moon? Of course we did. All you had to do was row out to it in a boat and, when you were underneath, prop a ladder against her and scramble up.Climbed up on the moon like this-

Now, you will ask me what in the world we went up on the Moon for; I'll explain it to you. We went to collect the...In simple words, Calvino leaves no stone unturned.

But the others also had wronged the Z'zus, to begin with, by calling them "immigrants," on the pretext that, since the others had been there first, the Z'zus had come later. This was mere unfounded prejudice -- that seems obvious to me -- because neither before nor after existed, nor any place to immigrate from, but there were those who insisted that the concept of "immigrant" could be understood in the abstract, outside of space and time.

There were three of them: an aunt and two uncles, all three very tall and practically identical; we never really understood which uncle was the husband and which the brother, or exactly how they were related to us: in those days there were many things that were left vague.

“Robbe-Grillet came out with a bitter attack on anthropomorphism, against the writer who still humanized the landscape. . . It is not that Robbe-Grillet’s argument didn’t convince me. It is just that in the course of writing I have come to take the oppostire route in stories that are a positive delirium of anthropomorphism, of the impossibility of thinking about the world except in terms of human figures. . . [I] multiplied his eyes and his nose in every direction until he no longer knows who he is.”The point of each story is to simultaneously laugh at how ridiculous it is to compare evolution to human social interaction, yet at the same time indulge, because how else do we know about the world around us? In Cosmicomics there is a particular sadness in each story, a loss and tragedy of understanding. Even the signs which we take to be words begins to break down, as the meanings of words proliferate and destabilize.

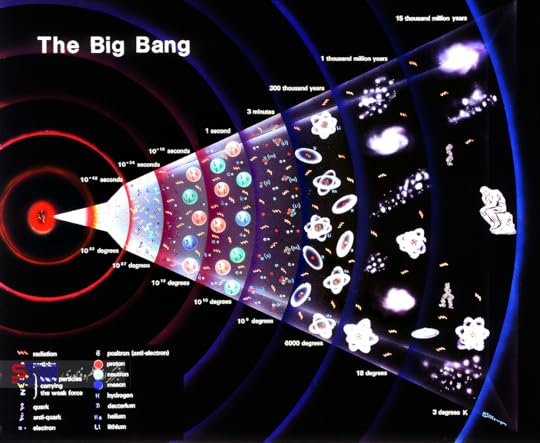

"I realized that with what seemed a casual jumple of words I had hit on an infinite reserve of new combinations among the signs which compact, opaque, uniform reality would use to disguise its monotony, and I realized that perhaps the race toward the future, the race I had been the first to foresee and desire, tended only—through time and space—toward a crumbling into alternatives like this, until it would dissolve in a geometry of invisible triangles and ricochets like the course of a football among the white lines of a field as I tried to imagine them, drawn at the bottom of the luminous vortex of the planetary systems, deciphering the numbers marked on the chests and backs of the players at night, unrecognizable in the distance."He takes anthropocentrism to its logical extreme. By applying human characteristic to even the most absurd of things—subatomic particles and the original point of matter from which the big bang sprung—he exposes it this "humanizing" for the absurdity it is.

“In the universe now there was no longer a container and a thing contained, but only a general thickness of signs superimposed and coagulated, occupying the whole volume of space; it was constantly being dotted, minutely, a network of lines and scratches and reliefs and engravings; the universe was scrawled over on all sides, along all its dimensions. There was no longer any way to establish a point of reference.”

“I first read Cosmicomics in my early 20s, and it's a book I've gone back to again and again. It is possibly the most enjoyable story collection ever written, a book that will frequently make you laugh out loud at its mischievous mastery, capricious ingenuity and nerve.”My favorite among the 12 stories is the first one: The Distance of the Moon where the moon and earth are still closed to each other and men can put up a ladder to climb to the moon. The close proximity of the moon and earth reminded me of the local legend told to us by our teachers here in the Philippines: that there was a man who had to use a wooden mortar and pestle to remove husk from the palay and produce rice. That every time he did that the sky became high and high until it became as far and high as it appears now.