What do you think?

Rate this book

320 pages, Hardcover

First published March 2, 2023

"Whereas sensory information was often considered to be the starting point of experience, the emerging science of the predictive brain suggests a rather different role. Now, the current sensory signal is used to refine and correct the process of informed guessing (the attempts at prediction) already taking place. It is now the predictions that do much of the heavy lifting. According to this new picture, experience—of the world, ourselves, and even our own bodies—is never a simple reflection of external or internal facts. Instead, all human experience arises at the meeting point of informed predictions and sensory stimulations.

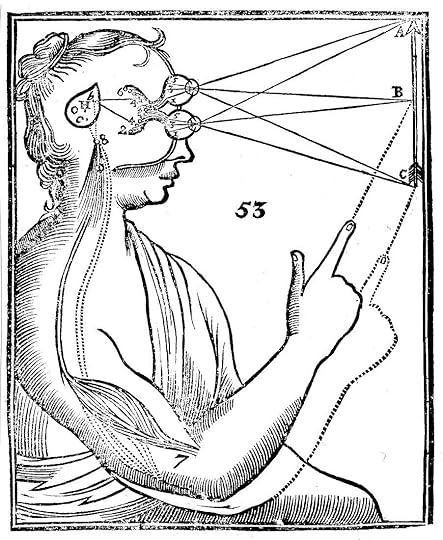

This is a profound change in our understanding of the mind that fundamentally alters how we should think about perception and the construction of human reality. For much of human history, scientists and philosophers saw perception as a process that worked mostly “from the outside in,” as light, sound, touch, and chemical odors activate receptors in eyes, ears, nose, and skin, progressively being refined into a richer picture of the wider world. Even well into the twenty-first century, leading models in both neuroscience and artificial intelligence retained core elements of that view.

The new science of predictive processing flips that traditional story on its head. Perception is now heavily shaped from the opposite direction, as predictions formed deep in the brain reach down to alter responses all the way down to areas closer to the skin, eyes, nose, and ears—the sensory organs that take in signals from the outside world. Incoming sensory signals help correct errors in prediction, but the predictions are in the driver’s seat now. This means that what we perceive today is deeply rooted in what we experienced yesterday, and all the days before that. Every aspect of our daily experience comes to us filtered by hidden webs of prediction—the brain’s best expectations rooted in our own past histories."

"...In this book, I draw on paradigm-shifting research to confront these crucial questions and ask what these insights mean for neuroscience, psychology, psychiatry, medicine, and how we live our lives. We’ll look hard at experiences of the body and self, from chronic pain to psychosis, and see how work on the predictive brain helps explain a wide spectrum of human behaviors and neurodiversity. We’ll reassess our own experiences of the world, from social anxiety and emotional feedback loops to the many forms of bias that can creep into our judgments. We’ll also explore some ways that predictive brains might support “extended minds,” blurring the boundaries between ourselves and our best-fitted tools and environments."

"This new understanding of the process of perceiving has real importance for our lives. It alters how we should think about the evidence of our own senses. It impacts how we should think about the way we experience our own bodily states—of pain, hunger, and other experiences such as feeling anxious or depressed. For the way our bodily states feel to us likewise reflects a complex mixture of what our brains predict and what the current bodily signals suggest. This means that we can, at times, change how we feel by changing what we (consciously or unconsciously) predict.

This does not mean we can simply “predict ourselves better,” nor does it mean we can alter our own experiences of pain or hunger in any way we choose. But it does suggest some principled and perhaps unexpected wiggle room—room that, with care and training, we might turn to our advantage.

Handled carefully, a better appreciation of the power of prediction could improve the way we think about our own medical symptoms and suggest new ways of understanding mental health, mental illness, and neurodiversity."