What do you think?

Rate this book

286 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2010

A pram pushed along a sidewalk as narrow as Main Street must navigate a frightening corridor of death and danger. On one side, inches away from its wheels, are rose bushes, each thorn of which can rip tender flesh open like a meat hook. Every bush may have dozens of roses, each with several thorns, and Main Street was lined with dozens of bushes. One false step, and unprotected skin could become lacerated with wounds so badly it would resemble a packet of Red Vines in a hurricane.

But that's the safe part. Only two or three feet to the left lay the open macadam of Main Street itself, a pulsating river of deadly metal. Consider that the top speed of a sprinter is somewhere around 20 to 23 miles per hour. Yet on Main Street, cars and buses weighing up to several tons flashed by at speeds close to twice that--any one of which could flatten a human being instantly, or crush it underneath its indifferent wheels. After the indescribable agony of a bus-on-carriage accident, death would be a pleasure.

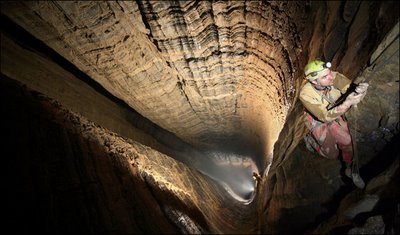

He wormed his way in and was digging out the floor to enlarge the passage when he spotted a mass of daddy longlegs hanging from the ceiling inches above his face. Seen from a distance, a daddy longlegs colony looked like a giant black beard growing on the rock. Seen from inches, the insects looked like big, hairy spiders. For the life of him, Clemmer could not remember whether they had a venomous bite. As long as he did not breathe or move, the colony was quiet. When he did either, the black beard burst into frantic motion. It could have been a scene straight from a Stephen King novel.It was interesting to learn that in terms of safety deep cave exploration has a lot more in common with extra-terrestrial exploration than it does with, say, mountain climbing. In case of injury, rescuers would have to not only complete the descent the explorer had already done, which could include having to scuba through extended underwater passages with only a few feet of visibility, but then bring the injured party back the way they came, possibly through passages that are so small that one must squeeze through inchworm-style. It is comparable to being stranded with an injury on Mars. A severe injury at great depths constitutes a death sentence.

"In fact, the subterranean world remains the greatest geographic unknown on this planet—called “the eighth continent” by some. Mountains, ocean depths, the moon, and even Martian scapes can be—and have been— revealed and explored by humans or our robotic surrogates. Not so caves.

They are the sole remaining realm that can be experienced only firsthand, by direct human presence..."

"As the new millennium dawned, the stage was thus set for an exploration drama unlike any since Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott competed, head-to-head, with results both horrible and historic, for the South Pole.

This book is the story of the race to make the last great discovery, and of the men and women who won and lost it."

"Supercaves create inner dangers as well, warping the mind with claustrophobia, anxiety, insomnia, hallucinations, personality disorders.

There is also a particularly insidious derangement unique to caves called The Rapture, which is like a panic attack on meth. It can strike anywhere in a cave, at any time, but usually assaults a caver deep underground.

And, of course, there is one more that, like getting lost, tends to be overlooked because it’s omnipresent: absolute, eternal darkness. Darkness so dark, without a single photon of light, that it is the luminal equivalent of absolute zero..."

"...It was not unusual for a digger to be wedged head-down in a vertical hole so tight that he could neither wear a helmet nor turn his head. To dig, he extended one arm down in front of his face, clawed and scraped material from the front of the hole, and ferried it backward, using his other hand to push the dirt out behind. Working this way, the digger resembled a swimmer doing the sidestroke.

Behind the digger came an assistant, who filled a bucket or pan and passed it back. And so on. Inverted in the hole, a digger was showered continually with dislodged dirt that worked its way into nose, mouth, ears, and eyes. Because carbon dioxide is heavier than air, the hole’s atmosphere became increasingly foul, requiring breaks to avoid blackout. Charco diggers spent many long hours like this..."