What do you think?

Rate this book

128 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1969

“La vida monótona y protegida de la familia resulta aburrida, y todo está permitido con tal de mantener la emoción. La vida, sin la desgracia es insoportable”Puede que si su madre no hubiera sido tan egoísta y distante, o su endiosado padre, ausente y decepcionante, o ambos menos liberales en sus relaciones, o su hermano no… pudiera ser que las cosas hubieran sido de otro modo. Puede que sí. Yo no lo creo, la niña protagonista de esta triste y perturbadora historia nació con esa semilla que hubiera germinado igualmente par hacer de su vida algo insoportablemente pequeño para la intensidad de sus deseos.

“… el sol luce estúpidamente en un cielo siempre azul”Imaginativa, creativa, apasionada, el sexo apareció en su vida cuando apenas tenía cinco o seis años, y lo hace con un ardor brutal. Un sexo siempre ligado al dolor, que ella busca con placer. Sus juegos preferidos son peligrosos y brutales. La monótona vida diaria es tan insuficiente que tiene que refugiarse constantemente en fantasías llenas de riesgos y horrores que sufre y goza con gran intensidad.

“El miedo es muy importante para ella. Ella ama el miedo y el horror”Obviamente, estas fantasías no bastan, la vida sigue siendo muy pequeña, el sexo es incapaz de aplacar su fuego, se siente vacía y triste, y el amor, único salvavidas posible, lo intuye insatisfactorio.

“… si él le diera un beso, se habría acabado el juego. Ella desea vivir siempre en la espera. Con el beso terminaría todo ¿Qué puede venir después? Al segundo beso, todo se hace costumbre”“Primavera sombría” es una novela cortísima, de apenas 60 páginas, escrita a base de frases esqueléticas, como si la autora tuviera unas ganas apremiantes de soltarlo todo y poder descansar. Parece buscar más la potencia de una imagen que la poesía de las palabras.

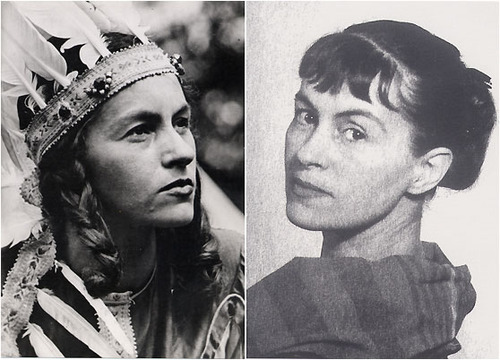

“La posibilidad de amar siempre con la misma intensidad sólo la tiene el que ama sin esperanza”Dicen que la novela tiene un fuerte carácter autobiográfico. Si es así, supongo que su escritura perseguía algún fin terapéutico, una catarsis con la que aliviar sus demonios, un escape a la tensión insoportable que tuvo que ser no poder salir de sí misma.

“They invent a howling theatrical language through which it becomes possible to express the grief of the whole world, a language understood by no one but the two of them.”

Now her room is almost dark. Only a distant street lamp glows faintly through the window. Now she no longer cares whether she dies on "foreign soil" or in her own garden. She steps onto the windowsill, holds herself fast to the cord of the shutter, and examines her shadowlike reflection in the mirror one last time. She finds herself lovely. A trace of regret mingles with her determination. "It's over," she says, quietly, and feels dead already, even before her feet leave the windowsill.

“How can we linger over books to which their authors have manifestly not been driven?”

Georges Bataille

The first man in her life is her father...