What do you think?

Rate this book

240 pages, Paperback

First published October 27, 1992

“—Tanto dolor y sufrimiento. Pero…, pero… — Pero ¿qué? — Pero… hermoso. Igual que besar lágrimas”El título es muy representativo de lo que aquí pueden encontrar, un hermoso libro sobre jazz y acerca de un puñado de grandes artistas de la era dorada de esta música maravillosa (mi edición es además un precioso ejemplar que publicó Círculo de lectores). Bien es cierto que lo disfrutarán mucho más aquellos que amen el jazz (entre los que me encuentro), pero el libro tiene valor literario en sí mismo, fue Premio Somerset Maugham en 1992.

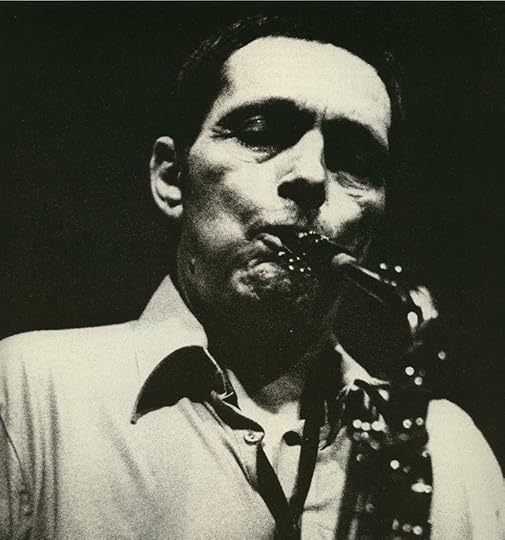

“… estaba el ritmo, detrás del ritmo el blues, detrás del blues, ese grito, el grito de aliento de los esclavos”Algo que llama poderosamente la atención en estos textos sobre episodios de la vida, reales o imaginados, de algunos grandes músicos (Lester Young, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Ben Webster, Charlie Mingus, Chet Baker y Art Pepper), con el hilo conductor de un viaje por carretera de Duke Ellington con Harry Carney, son unas circunstancias que comenta el autor en su epílogo:

“A cualquiera que se interese por el jazz, enseguida le llama la atención la alta tasa de víctimas entre quienes lo practican… Prácticamente todos los músicos negros de jazz fueron objeto de la discriminación racial y los malos tratos (Art Blakey, Miles Davis y Bud Powell recibieron palizas de la policía). Mientras que los contemporáneos de Coleman Hawkins y Lester Young, que dominaron el jazz en los años treinta, acabaron alcohólicos, la generación de músicos que forjó la revolución del bebop de los cuarenta y se consolidó en los cincuenta fue víctima, casi como epidemia, de adición a la heroína… La drogodependencia llevaba directamente… a la cárcel. El camino a las salas psiquiátricas de los hospitales, aunque más tortuoso, estaba igual de concurrido"En función de ello, el autor se pregunta si esta música no exige un tributo terrible a sus creadores. Si su extraordinario y rápido desarrollo a lo largo de las décadas de los 40, 50 y 60 no está en la base de tanta desgracia. Sin duda, el hecho de que esta música no se interprete nunca de la misma forma dos veces, que se cree música en el momento, exige unas mentes muy especiales y quizás proclives a excesos.

“… melodías que florecen y se marchitan como flores, el impulso que nunca pierde fuerza y sin esfuerzo se convierte en balada, las teclas se te ofrecen, compitiendo entre ellas por ser tocadas, como si el piano llevara esperando cien años la oportunidad de saber lo que se siente al ser una trompeta o un saxofón en manos de un negro” (del texto dedicado a Bud Powell)

- The fields on either side of the road were as dark as the night sky. The land was so flat that if you stood on a barn you could see the light of a car like stars on the horizon, pulling toward you for an hour before the red taillights ghosted slowly to the east. Except for the steady drone of the car there was no noise.

- He had written more hours of music than any other American and most of it began like this, scrawled on anything that came to hand: serviettes, envelopes, postcards, cardboard ripped from cereal packets.

- Hardly any of his music came to him as music. Everything started with a mood, an impression, something he’d seen or heard which he then translated into music.

- All the time he’d been travelling by train he’d stored up memories like that, searching later for a tone that corresponded to things he’d seen: colors like the baked red of evening in Santa Fe or flames licking yellow in the Ohio night, the whole sky flooded with the rust-color heat of furnaces…. Long train, said Harry at last

- It was not yet light but the darkness of night had given way to the predawn grayness when lights appear in houses and trees wait like thin cattle on the horizon.

- Yawning, Duke ordered the meal he had been living off for God knows how many years: steak and grapefruit, coffee. Harry asked for eggs and watched Duke slowly stir his coffee… The bags under his eyes suggested a backlog of missed sleep that would probably take ten years to clear.

- A thin attendant with bad teeth and a baseball cap limped out toward the pumps … He filled up the talk, grinning, and asked Harry if that was who he thought it was in the car. Harry nodded and Duke got out of the car, shook the guy’s thin fingers, and watched the happiness spread over his features like dawn over a dilapidated town.

- They drove on past billboards and tenements, railroad tracks and the dark entrances of thirstless bars.. It was a run-down town, smelling of dust and sad factories… Harry pulled up at a silver-fronted diner and went in to ask… he saw Harry, smiling, emerging from the diner and heading to the car… - Wrong town completely, Duke…

It seemed like he’d been here at the Alvin for ten years or more, ever since he got out of the stockade and out of the army … Gradually he’d stopped hanging out with the guys he played with, had taken to eating food in his room. Then he had stopped eating altogether, seeing practically no one and hardly leaving his room unless he had to. With every word addressed to him he shrank from the world a little further until the isolation went from being circumstantial to something he had internalized – but once that happened he realized it had always been there, the loneliness thing: in his playing it had always been there.

///

… was in 1957. He remembered the date but that got him nowhere. The problem was remembering how long ago 1957 was. Anyway, it was all very simple really: there was life before the army, which was sweet, then there was the army, a nightmare from which he’d never woken up.

///

He waited for the phone to ring, expecting to hear someone break the news to him that he had died in his sleep. He woke with a jolt and snatched up the silent phone. The receiver swallowed his words in two gulps like a snake. The sheets were wet as seaweed, the room full of the ocean mist of green neon.

When someone else was soloing he got up and did his dance… His dancing was a way of conducting, finding a way into the music. He had to get inside a piece … work himself into it like a drill biting into wood. Once he had buried himself in the song, knew it inside out, then he would play all around it, never inside it …

His body was his instrument and the piano was just a means of getting the sound out of his body at the rate and in the quantities he wanted …

He could do anything and it seemed right. He’d reach into his pocket for a handkerchief, grab it, and play with just that hand, holding the handkerchief, mopping up notes that have spilled from the keyboard, wipe his face while keeping the melody with the other hand as though playing the piano came as easy to him as blowing his nose.

///

- Once I complained that the runs he had asked for were impossible.

- You mean they don’t give you a chance to breath?

- No, but …

- Then you can play ‘em.

People were always telling him they couldn’t play things, but once he gave them a choice – You got an instrument? Well, you wanna play it or throw it away? – they found they could play. He made it seem stupid to be a musician and not be able to do things…

- Stop playing all this bullshit, man. Swing, if you can’t play anything else play the melody. Keep the beat all the time. Just because you’re not a drummer doesn’t mean you don’t gotta swing.

- Which of these notes should I hit?

- Hit any of ‘em, he said at last, his voice a gargle-murmur.

- And here, is that C sharp or C natural?

- Yeah, one a them

///

Nellie. If he had been a janitor she would have looked after him just the same as she did when they were jetting first class all over the world. Monk was helpless without her … She was so integral to his creative well-being that she may as well be credited as co-composer for most of his pieces.

///

- Yes, I would say there was a lot of sadness in him. The things that happened to him, most of it stayed in him. He let a little of that out in music … “Round Midnight,” that’s a sad song.

His rage never left him. Even when he was calm the pilot light of his anger was blinking away.

People said he was larger than life – as if life was a tiny feeble thing, a jacket several sizes too small, about to rip every time he moved.

Mingus Mingus Mingus – not a name but a verb, even thought was a form of action, internalized momentum.

Gradually he assumed the weight and dimensions of his instrument. He got so heavy that the bass was something he just slung over his shoulder like a duffel bag, hardly noticing the weight. The bigger he got, the smaller the bass became. He could bully it into doing what he wanted.

///

He picked up The New York Times and unfolded it roughly, flattened it out in the what-is-this-shit? way he reserved for newspapers… read with impatience, clutching it as if he were grabbing it by the lapels …

Sacked from Duke’s band for chasing Juan Tizol across the stage with a fire ax and splitting Tizol’s chair in two just as Duke was setting up “Take the A Train”. Smiling, Duke asked him later why he hadn’t let him know what was going to happen so he could have cued a few chords, written something into the score.

Nobody could put up with Mingus and Mingus refused to put up with anybody or anything… If he had been a ship the ocean would have been in his way.

///

Onstage he’d be yelling instructions, cussing out the rhythm section, calling out “Hold it, hold it” halfway through a piece because he didn’t like the way it was going, explaining to the audience that Jaki Byard couldn’t play shit and he was sacking him on the spot, starting the piece over again and rehiring the pianist half an hour later.

///

Mingus happy – nothing could beat the thrill, the rush of that. At full tilt the band felt like sprinting cheetahs, cheetahs chased by an elephant that always looked as though it might trample them underfoot.

///

In Germany he went on a rampage, smashing doors, microphones, recording equipment … His solos got heavier, swung with the movement of a gravedigger’s shovel, weighed down by damp earth… In Bellevue smells were the first thing he noticed… All through the night someone was screaming… the stiffness in his fingers never left now, some days they felt not simply stiff but numb… difficult to find the notes on the bass, knew where they were but unable to make the fingers grip… Now record companies were eager for everything he came up with, just the germ of an idea enough… talking was becoming difficult, his tongue lay in his mouth like an old man’s dick. Forming words like talking through a mouthful of wool… Than at the White House, an all-star concert and party. He in a wheelchair, trapped inside himself. When they called for a round of applause for the greatest living composer in jazz and everyone rose at once he broke down, tears streaming down his face, his body convulsed with great heaving sobs – the President running up to comfort him.

///

Mexico. When he was very weak he saw a bird hovering high in the sky, even its wings perfectly still. Its shadow lay in his lap; summoning all his energy he found the strength to stroke it, to ruffle its feathers.

- Hey, it’s good to see you Art..

- You too man … Hey, listen, can I cop from you?

- Man, you don’t change. How long you been out? Are we talking days, hours, or what?

- We’re talking minutes, man, said Art, smiling; Egg laughed out loud. So can I cop?

- You been out twenty minutes and you already looking to go straight back, said Egg, shaking his head. Whassamatter with you, man …

///

In San Quentin the grey prison fatigues make him feel like an actor performing scenes from the life of Art Pepper…

The black guy talks to a thin guy with an Afro and frightened eyes who trots off across the yard, returns with a dull-looking alto…

- Take us on a trip

- I haven’t touched a horn in a year.

- So now’s the time.

- I don’t know if I can still play.

- You can play.

… For a couple minutes he plays nothing but the melody, then begins to move away from it, cautiously …

After a flurry of twisted notes it seems there is nowhere for the solo to go. No one moves, the cons stand where they are, surrounding him like a fighter who has been beaten to the canvas…

Then, summoning everything, he searches for the highest note, reaches it – just – and soars clear…

When he finishes he is sweating. He nods his head so slightly it is like a twitch slowed right down. All around him is the silence of the prisoners listening…

No applause… Everyone aware now of the silence in the yard… Aware too that this silence is in appreciation of the music, an act of collective will, that there is always an inescapable dignity about silence… No one moves because in order for there to be silence in a place like this, time has to stop…

So they wait. The silence smolders; the longer it stews, the more violent will be its eventual eruption into noise… The silence is like a slowly expanding horizon, a view of distance…

The prisoners form a map, the contours of their gaze defining the pale figure who is breathing quietly, cradling the rusty alto in his arms, raising a hand to his mouth as he clears his throat.

///

1977. His first gig at the Vanguard in New York.

He is fifty-two, plays through a swamp of pain that leaves him clutching the horn like a crutch...he used to think about what he was playing, and while this distracted it also reassured because it meant that in between these spasms of self-consciousness he had simply been playing- and he played best when least conscious of what he was doing. At a certain point playing was a wild amnesia of technique"

///

In June, Laurie arranges an interview with the head psychiatrist of the hospital whose methadone program Art is enrolled in…

The doctor scribbles a few things in his notebook, among them, in handwriting deliberately more knotted than usual, a note reminding himself to track down some of the records this man has apparently made.

When I began writing this book I was unsure of the form it should take. This was a great advantage since it meant I had to improvise and so, from the start, the writing was animated by the defining characteristic of its subject.

Before long I found I had moved away from anything like conventional criticism. The metaphors and similes on which I relied to evoke what I thought was happening in the music came to seem increasingly inadequate. Moreover, since even the briefest simile introduces a hint of the fictive, it wasn't long before these metaphors were expanding themselves into episodes and scenes. As I invented dialogue and action, what was emerging came more and more to resemble fiction. At the same time, though, these scenes were still intended as commentary either on a piece of music or on the particular qualities of a musician. What follows, then, is as much imaginative criticism as fiction.

Many scenes have their origin in well-known or even legendary episodes: Chet Baker getting his teeth knocked out, for example. These episodes are part of a common repertory of anecdote and information -- “standards,” in other words, and I do my own versions of them, stating the identifying facts more or less briefly and then improvising around them, departing from them completely in some cases. This may mean being less than faithful to the truth but, once again, it keeps faith with the improvisational prerogatives of the form. Some episodes do not have their origins in fact: these wholly invented scenes can be seen as original compositions). […] Throughout, my purpose was to present the musicians not as they were but as they appear to me.