What do you think?

Rate this book

279 pages, Hardcover

First published February 1, 2011

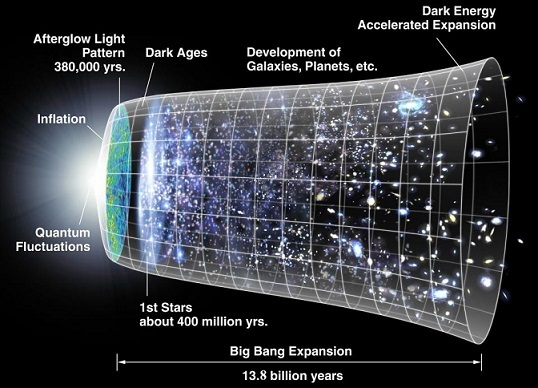

“Not the least!…Quantum theory is too parochial to address the question of existence. When you talk about a particle and an antiparticle appearing in the vacuum, that’s not at all like coming into existence out of nothing. The quantum vacuum is a highly structured thing that obeys deep and complex laws of physics. It’s not ‘nothingness’ in the philosophical sense at all. It’s not even as little as the kind of nothing you have in your bank account when there’s no money in it. I mean, there’s still the bank account! A quantum vacuum is much more even than an empty bank account, because it’s got structure. There’s stuff happening in it.” (p. 128)

“Indeed, such a unified theory might turn out to be the closest we can come to giving a complete physical explanation of why the world is the way it is. But the final theory of physics would still leave a residue of mystery—why this force, why this law? It would not contain within itself an answer to the question of why it was the final theory. So it would not live up to the principle that every fact must have an explanation—the Principle of Sufficient Reason.” (p. 78)

“[God] is a fitting ontological foundation for a contingent world. Yet he himself has no ontological foundation. His essence does not include existence. His being is not logically necessary. He might not have existed. There might have been no God, nothing at all.” (p. 119)