The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Hard Times

Hard Times

>

Book 1 Chp. 1-3

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

The second Chapter has the ominous title “Murdering the Innocents”, and it picks up the action where the preceding chapter left it. We are introduced by a rather sneering omniscient narrator to the schoolmaster Mr. Gradgrind, who is a man of facts, not only square in his views on life but also square of forefinger and square in the rest of his outward appearance – in a way the caricature of a utilitarian. He quizzes a new pupil, Sissy Jupe, the daughter of a carney, and finds her extremely deficient with regard to possessing the knowledge of facts. He even finds fault with her name, saying that Sissy is not a proper name and that she and her father ought to call her Cecilia instead. One of the other pupils, a boy named Bitzer, then gives the wished-for, encyclopedical definition of a horse.

His definition of a horse reminded me of Socrates and Plato’s well-structured way of defining all sorts of things, but also of Diogenes, who, on hearing that Plato rendered Socrates’s definition of man as “a featherless biped”, he brought a plucked chicken into the Academy and said, “Behold, I have brought you a man!”

Some consequences of Mr. Gradgrind’s education can already be seen in Bitzer, who is described as follows:

”His cold eyes would hardly have been eyes, but for the short ends of lashes which, by bringing them into immediate contrast with something paler than themselves, expressed their form. His short-cropped hair might have been a mere continuation of the sandy freckles on his forehead and face. His skin was so unwholesomely deficient in the natural tinge, that he looked as though, if he were cut, he would bleed white.”

It is probably also quite telling that the narrator makes a point of mentioning that the sunlight falling in through the windows first falls on Sissy Jupe and then, after passing a line of other pupils, comes last to Bitzer, who is apparently Mr. Gradgrind’s model student. At least, he calls him by his name, as opposed to Sissy, whom he calls Number Twenty. At this point, the second adult, a government official, takes up the interrogation, trying to prove that it is not proper to decorate houses with wallpapers showing horses or carpets that have pictures of flowers on them as in real life horses are never seen to walk on walls and people never tread on flowers. Later, the new teacher is going to take over the class, and his name is, quite characteristically, Mr. M’Choakumchild. He is described as the typical specimen of a teacher at common schools at that time: Full of undigested factual knowledge and prone to stifling children’s imagination.

His definition of a horse reminded me of Socrates and Plato’s well-structured way of defining all sorts of things, but also of Diogenes, who, on hearing that Plato rendered Socrates’s definition of man as “a featherless biped”, he brought a plucked chicken into the Academy and said, “Behold, I have brought you a man!”

Some consequences of Mr. Gradgrind’s education can already be seen in Bitzer, who is described as follows:

”His cold eyes would hardly have been eyes, but for the short ends of lashes which, by bringing them into immediate contrast with something paler than themselves, expressed their form. His short-cropped hair might have been a mere continuation of the sandy freckles on his forehead and face. His skin was so unwholesomely deficient in the natural tinge, that he looked as though, if he were cut, he would bleed white.”

It is probably also quite telling that the narrator makes a point of mentioning that the sunlight falling in through the windows first falls on Sissy Jupe and then, after passing a line of other pupils, comes last to Bitzer, who is apparently Mr. Gradgrind’s model student. At least, he calls him by his name, as opposed to Sissy, whom he calls Number Twenty. At this point, the second adult, a government official, takes up the interrogation, trying to prove that it is not proper to decorate houses with wallpapers showing horses or carpets that have pictures of flowers on them as in real life horses are never seen to walk on walls and people never tread on flowers. Later, the new teacher is going to take over the class, and his name is, quite characteristically, Mr. M’Choakumchild. He is described as the typical specimen of a teacher at common schools at that time: Full of undigested factual knowledge and prone to stifling children’s imagination.

Chapter 3, „A Loophole“, sees Mr. Gradgrind on his way home. We learn that Mr. Gradgrind used to be in the wholesale hardware trade before he founded a school and that his ambition is to be a Member of Parliament one day. He lives in a house called Stone Lodge and looking like that:

”A very regular feature on the face of the country, Stone Lodge was. Not the least disguise toned down or shaded off that uncompromising fact in the landscape. A great square house, with a heavy portico darkening the principal windows, as its master’s heavy brows overshadowed his eyes. A calculated, cast up, balanced, and proved house. Six windows on this side of the door, six on that side; a total of twelve in this wing, a total of twelve in the other wing; four-and-twenty carried over to the back wings. A lawn and garden and an infant avenue, all ruled straight like a botanical account-book. Gas and ventilation, drainage and water-service, all of the primest quality. Iron clamps and girders, fire-proof from top to bottom; mechanical lifts for the housemaids, with all their brushes and brooms; everything that heart could desire.”

We further learn that Mr. Gradgrind has five children and that these children are brought up entirely on a diet of facts, facts, facts, and that fancy and imagination have no place in their everyday lives:

”There were five young Gradgrinds, and they were models every one. They had been lectured at, from their tenderest years; coursed, like little hares. Almost as soon as they could run alone, they had been made to run to the lecture-room. The first object with which they had an association, or of which they had a remembrance, was a large black board with a dry Ogre chalking ghastly white figures on it.

Not that they knew, by name or nature, anything about an Ogre Fact forbid! I only use the word to express a monster in a lecturing castle, with Heaven knows how many heads manipulated into one, taking childhood captive, and dragging it into gloomy statistical dens by the hair.

No little Gradgrind had ever seen a face in the moon; it was up in the moon before it could speak distinctly. No little Gradgrind had ever learnt the silly jingle, Twinkle, twinkle, little star; how I wonder what you are! No little Gradgrind had ever known wonder on the subject, each little Gradgrind having at five years old dissected the Great Bear like a Professor Owen, and driven Charles’s Wain like a locomotive engine-driver. No little Gradgrind had ever associated a cow in a field with that famous cow with the crumpled horn who tossed the dog who worried the cat who killed the rat who ate the malt, or with that yet more famous cow who swallowed Tom Thumb: it had never heard of those celebrities, and had only been introduced to a cow as a graminivorous ruminating quadruped with several stomachs.”

On his way home, Mr. Gradgrind passes the “Sleary’s Horse-riding” pavilion and is dismayed to find some of his pupils spying on the show from the back of the booth. Having a closer look at the culprits dismays him even more because he finds that two of his own children, his mathematical son Thomas and his metallurgical daughter Louise of fifteen or sixteen years, are amongst them. He collars them and tells them off, whereupon Louisa confesses to having lured Thomas into coming with her. The children clearly show signs of their gloomy upbringing:

”There was an air of jaded sullenness in them both, and particularly in the girl: yet, struggling through the dissatisfaction of her face, there was a light with nothing to rest upon, a fire with nothing to burn, a starved imagination keeping life in itself somehow, which brightened its expression. Not with the brightness natural to cheerful youth, but with uncertain, eager, doubtful flashes, which had something painful in them, analogous to the changes on a blind face groping its way.”

His daughter tells him that she is tired – of everything, but he waves her words away and indignantly asks what Mr. Bounderby would say to all this. And here the chapter stops.

”A very regular feature on the face of the country, Stone Lodge was. Not the least disguise toned down or shaded off that uncompromising fact in the landscape. A great square house, with a heavy portico darkening the principal windows, as its master’s heavy brows overshadowed his eyes. A calculated, cast up, balanced, and proved house. Six windows on this side of the door, six on that side; a total of twelve in this wing, a total of twelve in the other wing; four-and-twenty carried over to the back wings. A lawn and garden and an infant avenue, all ruled straight like a botanical account-book. Gas and ventilation, drainage and water-service, all of the primest quality. Iron clamps and girders, fire-proof from top to bottom; mechanical lifts for the housemaids, with all their brushes and brooms; everything that heart could desire.”

We further learn that Mr. Gradgrind has five children and that these children are brought up entirely on a diet of facts, facts, facts, and that fancy and imagination have no place in their everyday lives:

”There were five young Gradgrinds, and they were models every one. They had been lectured at, from their tenderest years; coursed, like little hares. Almost as soon as they could run alone, they had been made to run to the lecture-room. The first object with which they had an association, or of which they had a remembrance, was a large black board with a dry Ogre chalking ghastly white figures on it.

Not that they knew, by name or nature, anything about an Ogre Fact forbid! I only use the word to express a monster in a lecturing castle, with Heaven knows how many heads manipulated into one, taking childhood captive, and dragging it into gloomy statistical dens by the hair.

No little Gradgrind had ever seen a face in the moon; it was up in the moon before it could speak distinctly. No little Gradgrind had ever learnt the silly jingle, Twinkle, twinkle, little star; how I wonder what you are! No little Gradgrind had ever known wonder on the subject, each little Gradgrind having at five years old dissected the Great Bear like a Professor Owen, and driven Charles’s Wain like a locomotive engine-driver. No little Gradgrind had ever associated a cow in a field with that famous cow with the crumpled horn who tossed the dog who worried the cat who killed the rat who ate the malt, or with that yet more famous cow who swallowed Tom Thumb: it had never heard of those celebrities, and had only been introduced to a cow as a graminivorous ruminating quadruped with several stomachs.”

On his way home, Mr. Gradgrind passes the “Sleary’s Horse-riding” pavilion and is dismayed to find some of his pupils spying on the show from the back of the booth. Having a closer look at the culprits dismays him even more because he finds that two of his own children, his mathematical son Thomas and his metallurgical daughter Louise of fifteen or sixteen years, are amongst them. He collars them and tells them off, whereupon Louisa confesses to having lured Thomas into coming with her. The children clearly show signs of their gloomy upbringing:

”There was an air of jaded sullenness in them both, and particularly in the girl: yet, struggling through the dissatisfaction of her face, there was a light with nothing to rest upon, a fire with nothing to burn, a starved imagination keeping life in itself somehow, which brightened its expression. Not with the brightness natural to cheerful youth, but with uncertain, eager, doubtful flashes, which had something painful in them, analogous to the changes on a blind face groping its way.”

His daughter tells him that she is tired – of everything, but he waves her words away and indignantly asks what Mr. Bounderby would say to all this. And here the chapter stops.

This book coming right after Bleak House, I see a certain overlap in the Gradgrind children and Mrs. Pardiggle's boys. We all know that children will not comply with their parents' obsessions, in the case of Gradgrind the obsession with facts, at least not voluntarily and wholeheartedly, and so does Dickens.

Apart from Sissy and Bitzer being on two separate ends of the beam of light, they were also described as very unlike each other. You could say Sissy is full of colour, with her dark hair and eyes, just as she is full of 'fancy'. Bitzer indeed has already had his fancy seeped out of him, and it shows, because the colour left with it.

Apart from Sissy and Bitzer being on two separate ends of the beam of light, they were also described as very unlike each other. You could say Sissy is full of colour, with her dark hair and eyes, just as she is full of 'fancy'. Bitzer indeed has already had his fancy seeped out of him, and it shows, because the colour left with it.

I really enjoyed the repetition of "facts" at the beginning. It established the teacher's character and the mood of the scene quite well.

I really enjoyed the repetition of "facts" at the beginning. It established the teacher's character and the mood of the scene quite well.The names cracked me up. Gradgrind (gradually grinds you down?) and Choakumchild (chokes children?). Imagine sending your kids to these people. Lol.

The boy and girl on opposite sides of the light beam was an interesting image. It seems to suggest they're connected in some otherworldly way.

Tristram wrote: "the beginning of the chapter with its repetition of the word “facts” is, to me, one of the beginnings of Dickens’s books I remember best ..."

Tristram wrote: "the beginning of the chapter with its repetition of the word “facts” is, to me, one of the beginnings of Dickens’s books I remember best ..."The opening of Hard Times is memorable for me because it was the first Dickens book I picked up to read on my own (i.e. it wasn't assigned by a teacher), and I think I was still in school - certainly not far beyond it - so I immediately identified with the classroom setting, and poor Sissy being put on the spot. Much more meaningful to me than the list of contradictions that open A Tale of Two Cities. By the way -- I'm sure the reason I decided to read it was its comparatively short length.

Alissa wrote: "The names cracked me up. Gradgrind (gradually grinds you down?) and Choakumchild (chokes children?). Imagine sending your kids to these people...."

Alissa wrote: "The names cracked me up. Gradgrind (gradually grinds you down?) and Choakumchild (chokes children?). Imagine sending your kids to these people...."M'Choakumchild is, perhaps, the least subtle of Dickens' character names, and that's saying something. It brings me to something that stood out to me as I read. I wonder if any of you had the same thought...

This is the first Dickens novel in which I felt as though Dickens was very self-aware. Do you know what I mean? Think of kids -- when they're babies and toddlers, they are genuine; every expression is pure and honest. But the day finally comes when they're laughing, not with pure joy, but because they know they should, or they're trying to manipulate a laugh from you. Or you take their picture and suddenly they're shy, or mugging for the camera. It's natural, but kind of sad to see them become self-aware that way.

In Dickens' case, I felt as if he was intentionally looking for that laugh line or quotable wisdom, particularly from the narrator. It didn't seem to be flowing naturally. The narrator seems to me to be less a passive observer, and more of a storyteller, interjecting remarks like the guy on Mystery Science Theater.

"If he had only learnt a little less, how infinitely better he might have taught much more!"

"If the greedy little Gradgrinds grasped at more than this, what was it for good gracious goodness' sake, that the greedy little Gradgrinds grasped it!"

And the mention of Grandgrind's squareness, for lack of a better word, was far from subtle. (By the way, what was Dickens' obsession with fingers?!)

I don't know... as I read it, it just seemed like Dickens was trying too hard compared to his other novels. Had this been his first book, I would have attributed it to inexperience. As it is, I wonder if he's just getting tired. After Copperfield and Bleak House one could hardly blame him for being a bit burned out.

Let's talk about the relationship between Louisa and Thomas Gradgrind, shall we?

Let's talk about the relationship between Louisa and Thomas Gradgrind, shall we? "Louisa looked at her father with more boldness than Thomas did. Indeed, Thomas did not look at him, but gave himself up to be taken home like a machine."

and this:

"‘Thomas, though I have the fact before me, I find it difficult to believe that you, with your education and resources, should have brought your sister to a scene like this.’

‘I brought _him_, father,’ said Louisa, quickly. ‘I asked him to come.’

‘I am sorry to hear it. I am very sorry indeed to hear it. It makes Thomas no better, and it makes you worse, Louisa.’

Louisa is very protective of her brother, and much bolder than he seems to be. In fact, we don't hear a word from Thomas during the entire exchange, though Gradgrind is expressing his displeasure mostly to the boy. The only thing we really hear about him is that he "gave himself up to be taken home like a machine", which is very sad. We know Louisa is 15 or 16. How old is Thomas, I wonder?

I had to look up Mrs. Grundy again ...

... a figurative name for an extremely conventional or priggish person, a personification of the tyranny of conventional propriety. A tendency to be overly fearful of what others might think is sometimes referred to as grundyism.

Makes me not very anxious to meet Mr. Bounderby, and feeling some anticipatory dread on behalf of poor Louisa.

No coincidence that the teacher in the Archie comic books was named Miss Grundy:

No coincidence that the teacher in the Archie comic books was named Miss Grundy:In the comics, she is the homeroom teacher at Riverdale High School, occasionally teaching English and math as well... Her name is derived from Mrs Grundy, a name that has been used to refer to a prudish woman since the early nineteenth century...

Despite occasional grumblings from her students, they seem to genuinely like and admire her. She, in return, tends to drive them hard... but remains quite fond of her students."

Mary Lou wrote: "I don't know... as I read it, it just seemed like Dickens was trying too hard compared to his other novels. Had this been his first book, I would have attributed it to inexperience. As it is, I wonder if he's just getting tired. After Copperfield and Bleak House one could hardly blame him for being a bit burned out."

Mary Lou wrote: "I don't know... as I read it, it just seemed like Dickens was trying too hard compared to his other novels. Had this been his first book, I would have attributed it to inexperience. As it is, I wonder if he's just getting tired. After Copperfield and Bleak House one could hardly blame him for being a bit burned out."I am maybe unsubtle but M'Choakumchild is one of my favorite Dickens names. :)

I agree, Mary Lou, that Dickens must have been primed for some burnout, but I don't know--I like the cleanness and efficiency of Hard Times compared to some of his more wandering earlier novels. I don't mind that it's packed with quotables--in fact I like that.

I do think it has more of a modern feel because it's so packed, as opposed to the lush drifty world-sketching that you get in the opening chapters of David Copperfield and Bleak House. But I see it as just a different kind of novel on that score, rather than inferior in its style.

I certainly enjoyed the name M'Choakumchild but as a non-native English speaker, I always feel some sort of happiness when I manage to work out the meaning of a pun. Apart from that, I really love puns, even bad ones, in both English and German.

I also noticed the frequency of quotable lines that Mary Lou pointed out and wondered whether there were any like that - apart from the characters' well-known catchphrases, such as "Barkis is willin'" - in Dickens's earlier novels. Maybe, this has also something to do with the novel's shortness? Dickens was used to writing very long novels, and Hard Times, coming after a real behemoth of a book, is his shortest novel. Maybe, Dickens was under the impression that it would be clever to put some of his central ideas into clever little sentences? He was just not used to writing a short novel, was he?

As to Louisa, I was intrigued by her tone of mild defiance towards her father. After Nell, Florence and all those other gentle sufferers, maybe we are finally getting a more truculent daughter figure here? I am afraid, though, that Dickens won't let it go too far because that kind of behaviour simply does not agree with his ideal picture of a young lady - but let's see. Plus, I would not be surprised to find some revenant of Rob the Grinder in young Thomas, who is too much of a product of his father's training.

I also noticed the frequency of quotable lines that Mary Lou pointed out and wondered whether there were any like that - apart from the characters' well-known catchphrases, such as "Barkis is willin'" - in Dickens's earlier novels. Maybe, this has also something to do with the novel's shortness? Dickens was used to writing very long novels, and Hard Times, coming after a real behemoth of a book, is his shortest novel. Maybe, Dickens was under the impression that it would be clever to put some of his central ideas into clever little sentences? He was just not used to writing a short novel, was he?

As to Louisa, I was intrigued by her tone of mild defiance towards her father. After Nell, Florence and all those other gentle sufferers, maybe we are finally getting a more truculent daughter figure here? I am afraid, though, that Dickens won't let it go too far because that kind of behaviour simply does not agree with his ideal picture of a young lady - but let's see. Plus, I would not be surprised to find some revenant of Rob the Grinder in young Thomas, who is too much of a product of his father's training.

After the door stoppers of D&S, DC, and BH I agree. Dickens may have been frayed at the edges. But then, is it more pressure to write shorter chapters on a weekly basis or lengthly chapters once a month? Candidly, I’m not sure. I remember once in my distant past I thought it would be an interesting experiment to write a chapter of Dickens but simply copying it out. In that way, partially at least, I could experience a chapter’s length in writing albeit without any thought or insight. I never followed through. A wise decision.

The shorter chapters bring fewer characters, fewer settings, much less sub-plot and the distinct possibility of fewer coincidences and back stories. All in all, a radical but exciting new direction.

The shorter chapters bring fewer characters, fewer settings, much less sub-plot and the distinct possibility of fewer coincidences and back stories. All in all, a radical but exciting new direction.

Mary Lou wrote: "Alissa wrote: "The names cracked me up. Gradgrind (gradually grinds you down?) and Choakumchild (chokes children?). Imagine sending your kids to these people...."

M'Choakumchild is, perhaps, the l..."

Mary Lou

I’ve never thought about the concept of self-awareness in this novel. It makes sense. I will follow the idea through the novel.

Fingers and Dickens, or, Dickens and Fingers. Surely there must be a Dickens article or book of criticism somewhere in the world. :-)

So many square objects. I found references to square fingers, walls, coats, legs, and shoulders. And that list is only from the first page of chapter one in my edition of the novel. Could it be the image of a square represents bluntness while blended to the fact that four sharp corners exist in a square? A square is a perfectly equal object. It offers no variety, no creativity, no curvature or subtlety. A square is the perfect shape of conformity. And that’s a fact.

And thank you for the link to popular culture. I had totally forgotten that Miss Grundy was the name of the homeroom/ Math/English teacher at Riverdale High. Pop culture linked to a Victorian staple. I can see the writers’ glee as they placed the name Grundy in a comic and wondered who would get the reference.

M'Choakumchild is, perhaps, the l..."

Mary Lou

I’ve never thought about the concept of self-awareness in this novel. It makes sense. I will follow the idea through the novel.

Fingers and Dickens, or, Dickens and Fingers. Surely there must be a Dickens article or book of criticism somewhere in the world. :-)

So many square objects. I found references to square fingers, walls, coats, legs, and shoulders. And that list is only from the first page of chapter one in my edition of the novel. Could it be the image of a square represents bluntness while blended to the fact that four sharp corners exist in a square? A square is a perfectly equal object. It offers no variety, no creativity, no curvature or subtlety. A square is the perfect shape of conformity. And that’s a fact.

And thank you for the link to popular culture. I had totally forgotten that Miss Grundy was the name of the homeroom/ Math/English teacher at Riverdale High. Pop culture linked to a Victorian staple. I can see the writers’ glee as they placed the name Grundy in a comic and wondered who would get the reference.

Fingers and Dickens is like noses and Tristram ;-)

As to squares, I like the idea of conformity in this context, Peter. Plus, the square suggests the idea of conventional wisdom readily packed up in neat little boxes. Not much room for creativity, is there?

As to the length of novels, or, in the case i am going to refer to, letters, they say this of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, viz. that he wrote in one of his letters that he did not have the time to write a short letter, and that's why, he said, he wrote a long one instead. This suggests that expressing things in brevity must require more forethought. By the way, this anecdote is not only ascribed to Goethe but to Mark Twain and other eminent people-of-letters as well. I can imagine that someone like Dickens, i.e. a person who has grown used to lengthy novels and monthly instalments might have felt out of his depth when suddenly faced with the task of writing in weekly instalments and having less room to develop his plot in.

As to squares, I like the idea of conformity in this context, Peter. Plus, the square suggests the idea of conventional wisdom readily packed up in neat little boxes. Not much room for creativity, is there?

As to the length of novels, or, in the case i am going to refer to, letters, they say this of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, viz. that he wrote in one of his letters that he did not have the time to write a short letter, and that's why, he said, he wrote a long one instead. This suggests that expressing things in brevity must require more forethought. By the way, this anecdote is not only ascribed to Goethe but to Mark Twain and other eminent people-of-letters as well. I can imagine that someone like Dickens, i.e. a person who has grown used to lengthy novels and monthly instalments might have felt out of his depth when suddenly faced with the task of writing in weekly instalments and having less room to develop his plot in.

From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:

"I wish you would look" (20th of January 1854) "at the enclosed titles for the H. W. story, between this and two o'clock or so, when I will call. It is my usual day, you observe, on which I have jotted them down—Friday! It seems to me that there are three very good ones among them. I should like to know whether you hit upon the same."

On the paper enclosed was written:

1. According to Cocker.

2. Prove it.

3. Stubborn Things.

4. Mr. Gradgrind's Facts.

5. The Grindstone.

6. Hard Times.

7. Two and Two are Four.

8. Something Tangible.

9. Our Hard-headed Friend.

10. Rust and Dust.

11. Simple Arithmetic.

12. A Matter of Calculation.

13. A Mere Question of Figures.

14. The Gradgrind Philosophy.

The three selected by me were 2, 6, and 11; the three that were his own favourites were 6, 13, and 14; and as 6 had been chosen by both, that title was taken.

It was the first story written by him for Household Words; and in the course of it the old troubles of the Clock came back, with the difference that the greater brevity of the weekly portions made it easier to write them up to time, but much more difficult to get sufficient interest into each.

"The difficulty of the space," he wrote after a few weeks' trial, "is crushing. Nobody can have an idea of it who has not had an experience of patient fiction-writing with some elbow-room always, and open places in perspective. In this form, with any kind of regard to the current number, there is absolutely no such thing."

He went on, however; and, of the two designs he started with, accomplished one very perfectly and the other at least partially. He more than doubled the circulation of his journal; and he wrote a story which, though not among his best, contains things as characteristic as any he has written.

"I wish you would look" (20th of January 1854) "at the enclosed titles for the H. W. story, between this and two o'clock or so, when I will call. It is my usual day, you observe, on which I have jotted them down—Friday! It seems to me that there are three very good ones among them. I should like to know whether you hit upon the same."

On the paper enclosed was written:

1. According to Cocker.

2. Prove it.

3. Stubborn Things.

4. Mr. Gradgrind's Facts.

5. The Grindstone.

6. Hard Times.

7. Two and Two are Four.

8. Something Tangible.

9. Our Hard-headed Friend.

10. Rust and Dust.

11. Simple Arithmetic.

12. A Matter of Calculation.

13. A Mere Question of Figures.

14. The Gradgrind Philosophy.

The three selected by me were 2, 6, and 11; the three that were his own favourites were 6, 13, and 14; and as 6 had been chosen by both, that title was taken.

It was the first story written by him for Household Words; and in the course of it the old troubles of the Clock came back, with the difference that the greater brevity of the weekly portions made it easier to write them up to time, but much more difficult to get sufficient interest into each.

"The difficulty of the space," he wrote after a few weeks' trial, "is crushing. Nobody can have an idea of it who has not had an experience of patient fiction-writing with some elbow-room always, and open places in perspective. In this form, with any kind of regard to the current number, there is absolutely no such thing."

He went on, however; and, of the two designs he started with, accomplished one very perfectly and the other at least partially. He more than doubled the circulation of his journal; and he wrote a story which, though not among his best, contains things as characteristic as any he has written.

Could one of you who is a teacher (you know who you are) please ask your class if they would put wallpaper with horses on it on their walls and flower carpets on their floors and let me know what they say?

The only artist to work on plates for the novel during Dickens's lifetime was the celebrated painter and magazine-illustrator Fred Walker, who began his career as an illustrator at Once a Week alongside the legendary George Du Maurier in 1860. For the 1868 Library Edition of Dickens works he contributed four illustrations to accompany Hard Times-- all signed with the initials "F. W. None of them are from this section though, so I guess I'll wait until we get there.

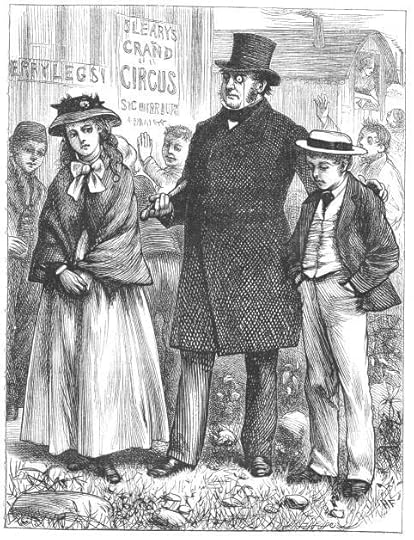

The next significant artist to illustrate the short novel was Harry French, who provided a comprehensive program of a frontispiece and nineteen full-size plates for the Household Edition published by Chapman and Hall in the 1870s. Here is the title page:

Thomas Gradgrind Apprehends His Children Louisa and Tom at the Circus

Book One, Chapter Three

Henry French

Text Illustrated:

Dumb with amazement, Mr. Gradgrind crossed to the spot where his family was thus disgraced, laid his hand upon each erring child, and said:

"Louisa!! Thomas!!"

Both rose, red and disconcerted. But, Louisa looked at her father with more boldness than Thomas did. Indeed, Thomas did not look at him, but gave himself up to be taken home like a machine.

Thomas Gradgrind Apprehends His Children Louisa and Tom at the Circus

Book One, Chapter Three

Henry French

Text Illustrated:

Dumb with amazement, Mr. Gradgrind crossed to the spot where his family was thus disgraced, laid his hand upon each erring child, and said:

"Louisa!! Thomas!!"

Both rose, red and disconcerted. But, Louisa looked at her father with more boldness than Thomas did. Indeed, Thomas did not look at him, but gave himself up to be taken home like a machine.

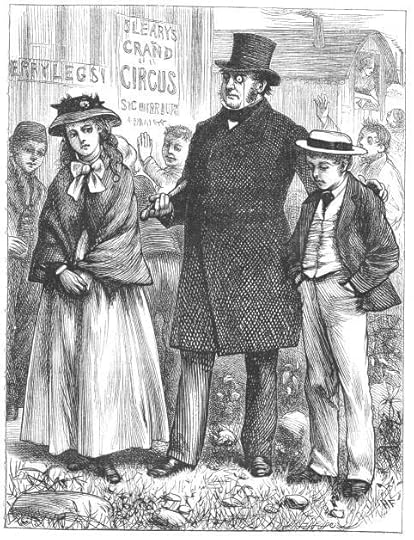

American-born but European-trained artist C. S. [Charles Stanley] Reinhart illustrated sixteen plates for Charles Dickens's Hard Times. They appeared in the single-volume, American version of the Household Edition published in 1876 by Harper & Brothers." Here is the first:

Book One, Chapter Three

C. S. Reinhart

Text Illustrated:

"Thomas Gradgrind took no heed of these trivialities of course, but passed on as a practical man ought to pass on, either brushing the noisy insects from his thoughts, or consigning them to the House of Correction. But, the turning of the road took him by the back of the booth, and at the back of the booth a number of children were congregated in a number of stealthy attitudes, striving to peep in at the hidden glories of the place.

This brought him to a stop. "Now, to think of these vagabonds," said he, "attracting the young rabble from a model school."

A space of stunted grass and dry rubbish being between him and the young rabble, he took his eyeglass out of his waistcoat to look for any child he knew by name, and might order off. Phenomenon almost incredible though distinctly seen, what did he then behold but his own metallurgical Louisa, peeping with all her might through a hole in a deal board, and his own mathematical Thomas abasing himself on the ground to catch but a hoof of the graceful equestrian Tyrolean flower-act!

Dumb with amazement, Mr. Gradgrind crossed to the spot where his family was thus disgraced, laid his hand upon each erring child, and said:

"Louisa!! Thomas!!"

Both rose, red and disconcerted. But, Louisa looked at her father with more boldness than Thomas did. Indeed, Thomas did not look at him, but gave himself up to be taken home like a machine.

Commentary:

Although the publisher, Harper and Brothers, has placed the second illustration immediately above the opening of the book, the moment illustrated comes in the third chapter, "A Loop-hole," when Thomas Gradgrind on his way home from his model school catches his two eldest children, Tom and Louisa, peeping "through a hole in a deal board" to watch the Tyrolean flower-act of the horse-riders. He has taken his eyeglass out of his waistcoat pocket to examine a number of children at the back of the booth, but Reinhart indicates just the two; as in the plate, in the text Louisa is standing and Tom is on the ground. In the background, Reinhart shows several circus wagons on the stubbly grass of "the neutral ground upon the outskirts of the town," and, on the horizon, the smoke-stacks of Coketown's satanic mills. Since, however, Gradgrind crosses the intervening ground to confront the malefactors in the text, one presumes he has already put his eyeglass back in his waistcoat pocket by the time we reach the moment Reinhart has chosen to depict. Furthermore, Louisa in Reinhart's picture seems a little younger than the pretty fifteen- or sixteen-year-old of the text — a not particularly fetching, in contrast to the Louisa whom Harry French has given the British reading public in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition.

While Tom and Louisa have both the natural curiosity and flexibility of youth, their father in his correct frockcoat, leather gloves, and top-hat (possibly a beaver) seems a wooden, black column — shades of Charlotte Brontë's description of the Reverend Mr. Brocklehurst as "a black pillar" in the Gateshead and Lowood sections of Jane Eyre (1847).

We are about to encounter a scene of submission and indoctrination in Coketown's schoolhouse in Chapter 2, "Murdering the Innocents." However, here the brother and sister, Tom and Louisa Gradgrind, the novel's central figures, are defying the Utilitarian precepts of their mentally inflexible parent. And yet, the philanthropist funding the other educational venture (if one accepts Dickens's notion that the circus, too, is intellectually as well as emotionally "improving"), the retired industrialist Thomas Gradgrind, is not the vicious disciplinarian that the Reverend Mr. Brocklehurst is at Lowood School. Thomas Gradgrind is well-meaning, but misguided — and Therefore faintly ridiculous.

However, as ensuing scenes make clear, Gradgrind like the black pillar master of Lowood suffers from a lack of human sympathy at the outset of the story, undervaluing emotion and "fancy." In Reinhart's plate for the third chapter, Gradgrind's eyeglass suggests that he cannot see what is immediately before him (his children peeping through a hole in the circus tent), and his cane may be poised to offer chastisement. Reinhart's Sixties' style style is in marked contrast to the careful detail (i. e., convincing the viewer of the verisimilitude of the illustration by painstaking details in the setting and costumes, in particular) of the previous generation of illustrators such as Phiz and Cruikshank, as his poster of the horse-riding acrobat (upper left) indicates.

A drawing of a prancing horse serves as an interesting headnote for the early chapters since in the second chapter Sissy Jupe fails to "define" a horse according to Gradgrind's formula, as exemplified by Bitzer's rote-memory definition. Reinhart accentuates the figures with fine cross-hatching, and gives an impression of such elements of setting as the tent, the grass, the waggons of Slearly's company indicative of the itinerant life-style, and the polluting smoke from the Coketown mills in the distance that spreads out across the cloudy skies above. In this modern perspective of the city, what dominates the distant skyline is not the belfries, steeples, and towers of places of worship, but the smoke-stacks and chimneys of Mammon, sponsoring deity of commerce and industry."

Book One, Chapter Three

C. S. Reinhart

Text Illustrated:

"Thomas Gradgrind took no heed of these trivialities of course, but passed on as a practical man ought to pass on, either brushing the noisy insects from his thoughts, or consigning them to the House of Correction. But, the turning of the road took him by the back of the booth, and at the back of the booth a number of children were congregated in a number of stealthy attitudes, striving to peep in at the hidden glories of the place.

This brought him to a stop. "Now, to think of these vagabonds," said he, "attracting the young rabble from a model school."

A space of stunted grass and dry rubbish being between him and the young rabble, he took his eyeglass out of his waistcoat to look for any child he knew by name, and might order off. Phenomenon almost incredible though distinctly seen, what did he then behold but his own metallurgical Louisa, peeping with all her might through a hole in a deal board, and his own mathematical Thomas abasing himself on the ground to catch but a hoof of the graceful equestrian Tyrolean flower-act!

Dumb with amazement, Mr. Gradgrind crossed to the spot where his family was thus disgraced, laid his hand upon each erring child, and said:

"Louisa!! Thomas!!"

Both rose, red and disconcerted. But, Louisa looked at her father with more boldness than Thomas did. Indeed, Thomas did not look at him, but gave himself up to be taken home like a machine.

Commentary:

Although the publisher, Harper and Brothers, has placed the second illustration immediately above the opening of the book, the moment illustrated comes in the third chapter, "A Loop-hole," when Thomas Gradgrind on his way home from his model school catches his two eldest children, Tom and Louisa, peeping "through a hole in a deal board" to watch the Tyrolean flower-act of the horse-riders. He has taken his eyeglass out of his waistcoat pocket to examine a number of children at the back of the booth, but Reinhart indicates just the two; as in the plate, in the text Louisa is standing and Tom is on the ground. In the background, Reinhart shows several circus wagons on the stubbly grass of "the neutral ground upon the outskirts of the town," and, on the horizon, the smoke-stacks of Coketown's satanic mills. Since, however, Gradgrind crosses the intervening ground to confront the malefactors in the text, one presumes he has already put his eyeglass back in his waistcoat pocket by the time we reach the moment Reinhart has chosen to depict. Furthermore, Louisa in Reinhart's picture seems a little younger than the pretty fifteen- or sixteen-year-old of the text — a not particularly fetching, in contrast to the Louisa whom Harry French has given the British reading public in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition.

While Tom and Louisa have both the natural curiosity and flexibility of youth, their father in his correct frockcoat, leather gloves, and top-hat (possibly a beaver) seems a wooden, black column — shades of Charlotte Brontë's description of the Reverend Mr. Brocklehurst as "a black pillar" in the Gateshead and Lowood sections of Jane Eyre (1847).

We are about to encounter a scene of submission and indoctrination in Coketown's schoolhouse in Chapter 2, "Murdering the Innocents." However, here the brother and sister, Tom and Louisa Gradgrind, the novel's central figures, are defying the Utilitarian precepts of their mentally inflexible parent. And yet, the philanthropist funding the other educational venture (if one accepts Dickens's notion that the circus, too, is intellectually as well as emotionally "improving"), the retired industrialist Thomas Gradgrind, is not the vicious disciplinarian that the Reverend Mr. Brocklehurst is at Lowood School. Thomas Gradgrind is well-meaning, but misguided — and Therefore faintly ridiculous.

However, as ensuing scenes make clear, Gradgrind like the black pillar master of Lowood suffers from a lack of human sympathy at the outset of the story, undervaluing emotion and "fancy." In Reinhart's plate for the third chapter, Gradgrind's eyeglass suggests that he cannot see what is immediately before him (his children peeping through a hole in the circus tent), and his cane may be poised to offer chastisement. Reinhart's Sixties' style style is in marked contrast to the careful detail (i. e., convincing the viewer of the verisimilitude of the illustration by painstaking details in the setting and costumes, in particular) of the previous generation of illustrators such as Phiz and Cruikshank, as his poster of the horse-riding acrobat (upper left) indicates.

A drawing of a prancing horse serves as an interesting headnote for the early chapters since in the second chapter Sissy Jupe fails to "define" a horse according to Gradgrind's formula, as exemplified by Bitzer's rote-memory definition. Reinhart accentuates the figures with fine cross-hatching, and gives an impression of such elements of setting as the tent, the grass, the waggons of Slearly's company indicative of the itinerant life-style, and the polluting smoke from the Coketown mills in the distance that spreads out across the cloudy skies above. In this modern perspective of the city, what dominates the distant skyline is not the belfries, steeples, and towers of places of worship, but the smoke-stacks and chimneys of Mammon, sponsoring deity of commerce and industry."

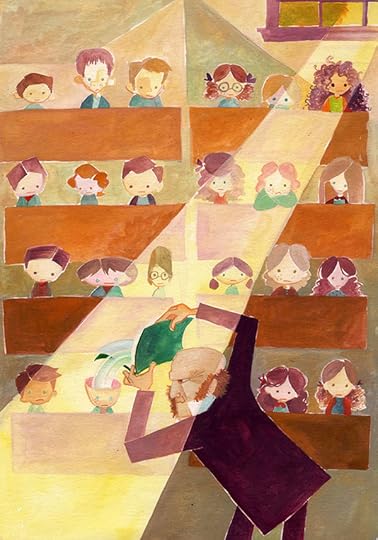

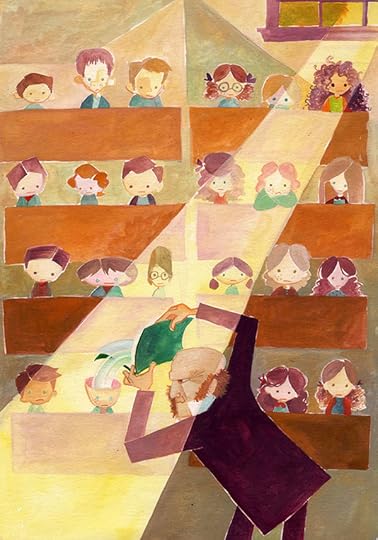

I also found this illustration, but I'm having trouble finding the artist:

"Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else."

That sunlight is giving me a migraine it's so bright. Of course having my head split open would also be like having a migraine. I'll let you know if I find the artist.

"Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else."

That sunlight is giving me a migraine it's so bright. Of course having my head split open would also be like having a migraine. I'll let you know if I find the artist.

Kim wrote: ""

Kim

The images are rather overwhelming. I’m going to suggest that horses and flowers need to be banned from HGTV shows.

Kim

The images are rather overwhelming. I’m going to suggest that horses and flowers need to be banned from HGTV shows.

Kim wrote: "The next significant artist to illustrate the short novel was Harry French, who provided a comprehensive program of a frontispiece and nineteen full-size plates for the Household Edition published ..."

Wow. A frontispiece and nineteen full illustrations. For a text of HT’s length the illustrations must have been tripping over each other.

As I look at this week’s illustrations I am reminded how much detail and iconography exists in those done by Phiz.

Wow. A frontispiece and nineteen full illustrations. For a text of HT’s length the illustrations must have been tripping over each other.

As I look at this week’s illustrations I am reminded how much detail and iconography exists in those done by Phiz.

Wow, I love the illustration with the sunbeam. It captures the imagery and metaphors from the story, a nice change of pace from the "realistic" drawings. In this one, Gradgrind has a square coat, rectangular arms, and is literally pouring facts in a child's head. Sissy is well-defined (with lots of curly hair!) and Bitzer is washed out by the light beam. Bitzer's open head reminds me of those monks who shave the top of their heads, leaving a ring of hair, supposedly so the "light of God" can enter.

Wow, I love the illustration with the sunbeam. It captures the imagery and metaphors from the story, a nice change of pace from the "realistic" drawings. In this one, Gradgrind has a square coat, rectangular arms, and is literally pouring facts in a child's head. Sissy is well-defined (with lots of curly hair!) and Bitzer is washed out by the light beam. Bitzer's open head reminds me of those monks who shave the top of their heads, leaving a ring of hair, supposedly so the "light of God" can enter.Edit: I just noticed, too, that the book is an extension of Gradgrind's head, as if he's pouring his own knowledge into the child. Also, there is a girl in the sunbeam with her elbows on the desk. She's the only one in the class doing that. Hmmm... The class is split down the middle, as well.

Alissa wrote: "I really enjoyed the repetition of "facts" at the beginning. It established the teacher's character and the mood of the scene quite well.

Alissa wrote: "I really enjoyed the repetition of "facts" at the beginning. It established the teacher's character and the mood of the scene quite well.The names cracked me up. Gradgrind (gradually grinds you d..."

I had not thought, with regard to Gradgrind, that it could signal a gradual grinding down. I like how this works, though. My initial reaction, when introduced to the name and imploring of facts from students, was that the “grad” part of the name was for graduates.

John wrote: "My initial reaction, when introduced to the name and imploring of facts from students, was that the “grad” part of the name was for graduates."

John wrote: "My initial reaction, when introduced to the name and imploring of facts from students, was that the “grad” part of the name was for graduates."I thought of graduate too, and the square hats.

I love the name "Stubborn Things" which works both for facts and people.

I love the name "Stubborn Things" which works both for facts and people. Reinhart's Louisa looks like a middle-aged woman.

I, too, enjoy the illustration with the facts being poured directly into the child's head.

As for the horse wallpaper and the example of floral carpet Kim chose, allow me to refer you to a facebook page I recently discovered called Nightmare on Zillow Street. Go there when you need to feel good about your housekeeping, decorating style, or even just your sanity. Kim's selections would surely fit right in with some of the other decor featured there. :-)

https://www.facebook.com/groups/22813...

Alissa wrote: "Wow, I love the illustration with the sunbeam. It captures the imagery and metaphors from the story, a nice change of pace from the "realistic" drawings. In this one, Gradgrind has a square coat, r..."

Alissa wrote: "Wow, I love the illustration with the sunbeam. It captures the imagery and metaphors from the story, a nice change of pace from the "realistic" drawings. In this one, Gradgrind has a square coat, r..."Yes. I enjoyed that one, too. It's so fun to see all the original illustrations, but also intriguing to see this illustration reaching across history. Thanks, Kim!

Kim wrote: ""The difficulty of the space," he wrote after a few weeks' trial, "is crushing. Nobody can have an idea of it who has not had an experience of patient fiction-writing with some elbow-room always, and open places in perspective."

Kim wrote: ""The difficulty of the space," he wrote after a few weeks' trial, "is crushing. Nobody can have an idea of it who has not had an experience of patient fiction-writing with some elbow-room always, and open places in perspective."Love this quote. Doesn't sound like Dickens was one of those writers afraid of the blank page.

Kim wrote: "The only artist to work on plates for the novel during Dickens's lifetime was the celebrated painter and magazine-illustrator Fred Walker, who began his career as an illustrator at Once a Week alon..."

I hardly dare asking my students a question like that because I can well imagine that the entire lesson would be done for once I got my 6th graders started on this. They can talk for hours on any topic not related with the lesson.

I hardly dare asking my students a question like that because I can well imagine that the entire lesson would be done for once I got my 6th graders started on this. They can talk for hours on any topic not related with the lesson.

Kim wrote: "I also found this illustration, but I'm having trouble finding the artist:

"Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing..."

I love that picture, Kim! I wonder who the "Cocker" referred to in the first title suggestion might be. My first Google inquiry landed me with spaniels, which did not surprise me ;-)

"Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing..."

I love that picture, Kim! I wonder who the "Cocker" referred to in the first title suggestion might be. My first Google inquiry landed me with spaniels, which did not surprise me ;-)

Tristram wrote: "I wonder who the "Cocker" referred to in the first title suggestion might be. My first Google inquiry landed me with spaniels, which did not surprise me..."

Tristram wrote: "I wonder who the "Cocker" referred to in the first title suggestion might be. My first Google inquiry landed me with spaniels, which did not surprise me..."Perhaps that solves the mystery of what breed Merrylegs is, though I still contend (from our last time reading this book) that he's a terrier of some kind. But now that I have a x-dachshund, maybe I should start picturing Merrylegs as looking like my Pip. :-)

Tristram wrote: "The second Chapter has the ominous title “Murdering the Innocents”, and it picks up the action where the preceding chapter left it. We are introduced by a rather sneering omniscient narrator to the..."

Here is a section of a speech by Dickens he gave in 1857 telling the listeners of the schools he "did not like".

SPEECH: LONDON, NOVEMBER 5, 1857.

Speech given by Charles Dickens at the fourth anniversary dinner of the Warehousemen and Clerks Schools

Thursday evening, Nov. 5th, 1857,

The London Tavern

On the subject which had brought the company together Mr. Dickens spoke as follows:

"I must now solicit your attention for a few minutes to the cause of your assembling together — the main and real object of this evening’s gathering; for I suppose we are all agreed that the motto of these tables is not “Let us eat and drink, for to-morrow we die;” but, “Let us eat and drink, for to-morrow we live.” It is because a great and good work is to live to-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow, and to live a greater and better life with every succeeding to-morrow, that we eat and drink here at all. Conspicuous on the card of admission to this dinner is the word “Schools.”

This set me thinking this morning what are the sorts of schools that I don’t like. I found them on consideration, to be rather numerous. I don’t like to begin with, and to begin as charity does at home — I don’t like the sort of school to which I once went myself — the respected proprietor of which was by far the most ignorant man I have ever had the pleasure to know; one of the worst-tempered men perhaps that ever lived, whose business it was to make as much out of us and put as little into us as possible, and who sold us at a figure which I remember we used to delight to estimate, as amounting to exactly 2 pounds 4s. 6d. per head. I don’t like that sort of school, because I don’t see what business the master had to be at the top of it instead of the bottom, and because I never could understand the wholesomeness of the moral preached by the abject appearance and degraded condition of the teachers who plainly said to us by their looks every day of their lives, “Boys, never be learned; whatever you are, above all things be warned from that in time by our sunken cheeks, by our poor pimply noses, by our meagre diet, by our acid-beer, and by our extraordinary suits of clothes, of which no human being can say whether they are snuff-coloured turned black, or black turned snuff-coloured, a point upon which we ourselves are perfectly unable to offer any ray of enlightenment, it is so very long since they were undarned and new.” I do not like that sort of school, because I have never yet lost my ancient suspicion touching that curious coincidence that the boy with four brothers to come always got the prizes. In fact, and short, I do not like that sort of school, which is a pernicious and abominable humbug, altogether.

Again, ladies and gentlemen, I don’t like that sort of school — a ladies’ school — with which the other school used to dance on Wednesdays, where the young ladies, as I look back upon them now, seem to me always to have been in new stays and disgrace — the latter concerning a place of which I know nothing at this day, that bounds Timbuctoo on the north-east — and where memory always depicts the youthful enthraller of my first affection as for ever standing against a wall, in a curious machine of wood, which confined her innocent feet in the first dancing position, while those arms, which should have encircled my jacket, those precious arms, I say, were pinioned behind her by an instrument of torture called a backboard, fixed in the manner of a double direction post.

Again, I don’t like that sort of school, of which we have a notable example in Kent, which was established ages ago by worthy scholars and good men long deceased, whose munificent endowments have been monstrously perverted from their original purpose, and which, in their distorted condition, are struggled for and fought over with the most indecent pertinacity.

Again, I don’t like that sort of school — and I have seen a great many such in these latter times — where the bright childish imagination is utterly discouraged, and where those bright childish faces, which it is so very good for the wisest among us to remember in after life — when the world is too much with us, early and late 22 — are gloomily and grimly scared out of countenance; where I have never seen among the pupils, whether boys or girls, anything but little parrots and small calculating machines.

Again, I don’t by any means like schools in leather breeches, and with mortified straw baskets for bonnets, which file along the streets in long melancholy rows under the escort of that surprising British monster — a beadle, whose system of instruction, I am afraid, too often presents that happy union of sound with sense, of which a very remarkable instance is given in a grave report of a trustworthy school inspector, to the effect that a boy in great repute at school for his learning, presented on his slate, as one of the ten commandments, the perplexing prohibition, “Thou shalt not commit doldrum.”

Ladies and gentlemen, I confess, also, that I don’t like those schools, even though the instruction given in them be gratuitous, where those sweet little voices which ought to be heard speaking in very different accents, anathematise by rote any human being who does not hold what is taught there.

Lastly, I do not like, and I did not like some years ago, cheap distant schools, where neglected children pine from year to year under an amount of neglect, want, and youthful misery far too sad even to be glanced at in this cheerful assembly."

Here is a section of a speech by Dickens he gave in 1857 telling the listeners of the schools he "did not like".

SPEECH: LONDON, NOVEMBER 5, 1857.

Speech given by Charles Dickens at the fourth anniversary dinner of the Warehousemen and Clerks Schools

Thursday evening, Nov. 5th, 1857,

The London Tavern

On the subject which had brought the company together Mr. Dickens spoke as follows:

"I must now solicit your attention for a few minutes to the cause of your assembling together — the main and real object of this evening’s gathering; for I suppose we are all agreed that the motto of these tables is not “Let us eat and drink, for to-morrow we die;” but, “Let us eat and drink, for to-morrow we live.” It is because a great and good work is to live to-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow, and to live a greater and better life with every succeeding to-morrow, that we eat and drink here at all. Conspicuous on the card of admission to this dinner is the word “Schools.”

This set me thinking this morning what are the sorts of schools that I don’t like. I found them on consideration, to be rather numerous. I don’t like to begin with, and to begin as charity does at home — I don’t like the sort of school to which I once went myself — the respected proprietor of which was by far the most ignorant man I have ever had the pleasure to know; one of the worst-tempered men perhaps that ever lived, whose business it was to make as much out of us and put as little into us as possible, and who sold us at a figure which I remember we used to delight to estimate, as amounting to exactly 2 pounds 4s. 6d. per head. I don’t like that sort of school, because I don’t see what business the master had to be at the top of it instead of the bottom, and because I never could understand the wholesomeness of the moral preached by the abject appearance and degraded condition of the teachers who plainly said to us by their looks every day of their lives, “Boys, never be learned; whatever you are, above all things be warned from that in time by our sunken cheeks, by our poor pimply noses, by our meagre diet, by our acid-beer, and by our extraordinary suits of clothes, of which no human being can say whether they are snuff-coloured turned black, or black turned snuff-coloured, a point upon which we ourselves are perfectly unable to offer any ray of enlightenment, it is so very long since they were undarned and new.” I do not like that sort of school, because I have never yet lost my ancient suspicion touching that curious coincidence that the boy with four brothers to come always got the prizes. In fact, and short, I do not like that sort of school, which is a pernicious and abominable humbug, altogether.

Again, ladies and gentlemen, I don’t like that sort of school — a ladies’ school — with which the other school used to dance on Wednesdays, where the young ladies, as I look back upon them now, seem to me always to have been in new stays and disgrace — the latter concerning a place of which I know nothing at this day, that bounds Timbuctoo on the north-east — and where memory always depicts the youthful enthraller of my first affection as for ever standing against a wall, in a curious machine of wood, which confined her innocent feet in the first dancing position, while those arms, which should have encircled my jacket, those precious arms, I say, were pinioned behind her by an instrument of torture called a backboard, fixed in the manner of a double direction post.

Again, I don’t like that sort of school, of which we have a notable example in Kent, which was established ages ago by worthy scholars and good men long deceased, whose munificent endowments have been monstrously perverted from their original purpose, and which, in their distorted condition, are struggled for and fought over with the most indecent pertinacity.

Again, I don’t like that sort of school — and I have seen a great many such in these latter times — where the bright childish imagination is utterly discouraged, and where those bright childish faces, which it is so very good for the wisest among us to remember in after life — when the world is too much with us, early and late 22 — are gloomily and grimly scared out of countenance; where I have never seen among the pupils, whether boys or girls, anything but little parrots and small calculating machines.

Again, I don’t by any means like schools in leather breeches, and with mortified straw baskets for bonnets, which file along the streets in long melancholy rows under the escort of that surprising British monster — a beadle, whose system of instruction, I am afraid, too often presents that happy union of sound with sense, of which a very remarkable instance is given in a grave report of a trustworthy school inspector, to the effect that a boy in great repute at school for his learning, presented on his slate, as one of the ten commandments, the perplexing prohibition, “Thou shalt not commit doldrum.”

Ladies and gentlemen, I confess, also, that I don’t like those schools, even though the instruction given in them be gratuitous, where those sweet little voices which ought to be heard speaking in very different accents, anathematise by rote any human being who does not hold what is taught there.

Lastly, I do not like, and I did not like some years ago, cheap distant schools, where neglected children pine from year to year under an amount of neglect, want, and youthful misery far too sad even to be glanced at in this cheerful assembly."

An impressive speech, Kim, and I think that of most of these schools Dickens gave us an example in one of his novels.

Kim wrote: "1. According to Cocker."

You may remember that earlier on in this thread I wondered who this Cocker was and that I could not really understand the meaning behind this title.

I am reading an earlier Penguin edition of this novel, with annotations by David Craig, and in one note to Chapter 8 he gave some information on Cocker (not Joe, unluckily), which I am going to quote here:

Another short Internet search taught me that the man's Christian name was Edward.

You may remember that earlier on in this thread I wondered who this Cocker was and that I could not really understand the meaning behind this title.

I am reading an earlier Penguin edition of this novel, with annotations by David Craig, and in one note to Chapter 8 he gave some information on Cocker (not Joe, unluckily), which I am going to quote here:

"a seventeenth-century mathematician whose book on arithmetic ran into so many editions (c.60) that from about 1760 the phrase 'according to Cocker' became proverbial, meaning 'perfectly correct factually' or 'precisely according to the rules'. The phrase was on Dickens's short-list of titles for Hard Times."

Another short Internet search taught me that the man's Christian name was Edward.

I found this looking for illustrations, there are no spoilers:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j0Mqy...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j0Mqy...

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "The second Chapter has the ominous title “Murdering the Innocents”, and it picks up the action where the preceding chapter left it. We are introduced by a rather sneering omniscien..."

The last paragraph of Dickens’s speech resonated to my core. The continuing revelations about what happened in Canada's residential schools mirror almost exactly what Dickens writes.

The last paragraph of Dickens’s speech resonated to my core. The continuing revelations about what happened in Canada's residential schools mirror almost exactly what Dickens writes.

Peter, can you link an article as to what is happening at Canadian schools? Canada is not often covered on the German news.

Tristram

Here you are. What has been occurring in Canada recently is the discovery of many hundreds of unmarked graves on the premises of multiple residential schools.

As a nation Canada has been blindly aware of how the colonists and then our nation right up to the 1970’s treated Canada’s indigenous population. We are now learning (and seeing) in real time elements of our nation’s history.

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.c...

Here you are. What has been occurring in Canada recently is the discovery of many hundreds of unmarked graves on the premises of multiple residential schools.

As a nation Canada has been blindly aware of how the colonists and then our nation right up to the 1970’s treated Canada’s indigenous population. We are now learning (and seeing) in real time elements of our nation’s history.

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.c...

Kim wrote: "

"Louisa!! Thomas!!"

Ron Embleton

Chapter 3"

I have been drawn back to this illustration a few times in our reading. I couldn’t put my finger on exactly why until I reread the introduction to the Penguin edition of Hard Times written by David Craig. Then the lightning bolt (or was it the hoof of Pegasus) struck.

Embleton’s illustration has many children peering into the world of Sleary’s circus. The poster displays the name of Merrylegs. Three of the six children in the picture are barefoot. The youngest of the children is being restrained from peering into the world of the circus by her mother.

Hovering over the children is the impeccably dressed Mr Gradgrind. He represents the repressive school system. Behind him, we see the clear outline of a factory. Together, Gradgrind and the mill are the emblems of repression that are hard at work trying to grind out any degree of fascination, joy, wonder, or imagination from the obviously already physically impoverished children. Soon, under Gradgrind and Bounderby, these children will be intellectually starved and their imaginations destroyed.

Merrylegs versus Gradgrind and Bounderby.

What a powerful illustration.

"Louisa!! Thomas!!"

Ron Embleton

Chapter 3"

I have been drawn back to this illustration a few times in our reading. I couldn’t put my finger on exactly why until I reread the introduction to the Penguin edition of Hard Times written by David Craig. Then the lightning bolt (or was it the hoof of Pegasus) struck.

Embleton’s illustration has many children peering into the world of Sleary’s circus. The poster displays the name of Merrylegs. Three of the six children in the picture are barefoot. The youngest of the children is being restrained from peering into the world of the circus by her mother.

Hovering over the children is the impeccably dressed Mr Gradgrind. He represents the repressive school system. Behind him, we see the clear outline of a factory. Together, Gradgrind and the mill are the emblems of repression that are hard at work trying to grind out any degree of fascination, joy, wonder, or imagination from the obviously already physically impoverished children. Soon, under Gradgrind and Bounderby, these children will be intellectually starved and their imaginations destroyed.

Merrylegs versus Gradgrind and Bounderby.

What a powerful illustration.

Thanks for sharing the youtube video, Kim. I enjoyed the animation.

Thanks for sharing the youtube video, Kim. I enjoyed the animation. Awful about the schools. Thank goodness it's come to light.

I was told about this documentary by a friend of mine who knows I love Dickens and thought I might find it interesting. You might, too. Thankfully, the orphans at this school seem to have fared better than the indigenous children in Canada. My library carried the DVD:

https://www.visionvideo.com/dvd/50093...

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "

"Louisa!! Thomas!!"

Ron Embleton

Chapter 3"

I have been drawn back to this illustration a few times in our reading. I couldn’t put my finger on exactly why until I reread the intro..."

Brilliant interpretation, Peter!

"Louisa!! Thomas!!"

Ron Embleton

Chapter 3"

I have been drawn back to this illustration a few times in our reading. I couldn’t put my finger on exactly why until I reread the intro..."

Brilliant interpretation, Peter!

Peter wrote: "Tristram

Here you are. What has been occurring in Canada recently is the discovery of many hundreds of unmarked graves on the premises of multiple residential schools.

As a nation Canada has been..."

That is a very shocking report, Peter. When I read it yesterday, it reminded me a bit of what happened in Australia, but I did not know that a similar thing happened in Canada.

Here you are. What has been occurring in Canada recently is the discovery of many hundreds of unmarked graves on the premises of multiple residential schools.

As a nation Canada has been..."

That is a very shocking report, Peter. When I read it yesterday, it reminded me a bit of what happened in Australia, but I did not know that a similar thing happened in Canada.

I don’t know about you but for me time seemed to stand still or at least to move more slowly than usual without our weekly Dickens discussions. I must confess that I don’t have too great expectations in Hard Times – but then I did not have particularly hard times reading Great Expectations – because it is such a short book, and I really like Dickens’s characters accompanying me for a longer time. On the other hand, reading the first part as it was read by contemporary readers makes up for that shortness to some degree.

The first Chapter, however, which is called “The One Thing Needful”, is extremely short, so short even that I cannot by any means quote from it but could instead copy the whole chapter. Which I won’t do. It introduces us into the scene of a schoolroom without giving any names. Instead, all we learn is that there are three adult people in it and a lot of pupils – and one of the adults is giving a short lecture on the importance of teaching facts – and facts only – to young children. By the way, the beginning of the chapter with its repetition of the word “facts” is, to me, one of the beginnings of Dickens’s books I remember best – along with the beginnings of David Copperfield, Bleak House, Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities.

It might also be added here that the three Parts of Hard Times bear the titles “Sowing”, “Reaping” and “Garnering”, which, at first sight, is quite odd since these terms clearly refer to agriculture whereas the novel is set in an industrial town and deals with trade unionism and the plights of workers. However, when one looks at the first words of Mr. Gradgrind, i.e. at his encomium on facts, one will find that he uses metaphors of “planting” facts and “rooting out” everything else and that he says that not only does he use this principle when teaching his pupils but that he also brings up his own children this way. Maybe the novel will give us some insight into what Mr. Gradgrind will harvest in the end?

A note on the language: I could not help laughing at finding that the heavy use of metaphor in the description of Mr. Gradgrind, and later in commenting on the matter-of-fact outlook on life adopted by that eminent gentleman runs counter to the spirit Mr. Gradgrind tries to instill into the young people entrusted to his care. May this just be a coincidence, or does Dickens do this on purpose – and to what end?