Rod Dreher's Blog, page 662

September 28, 2015

The Untidiness of Freedom

Another triumph for US policy in the Mideast:

Syrian rebels trained by the United States gave some of their equipment to the al Qaeda-linked Nusra Front in exchange for safe passage, a U.S. military spokesman said on Friday, the latest blow to a troubled U.S. effort to train local partners to fight Islamic State militants.

The rebels surrendered six pick-up trucks and some ammunition, or about one-quarter of their issued equipment, to a suspected Nusra intermediary on Sept. 21-22 in exchange for safe passage, said Colonel Patrick Ryder, a spokesman for U.S. Central Command, in a statement.

“If accurate, the report of NSF members providing equipment to al Nusra Front is very concerning and a violation of Syria train and equip program guidelines,” Ryder said, using an acronym for the rebels, called the New Syrian Forces.

It’s almost like we don’t know who is trustworthy and/or capable in that region. Imagine that.

In more Mission Accomplished news:

Even as the U.S. military denies reports that American troops were told to ignore Afghan child abusers, an 11-year Green Beret who was ordered discharged after he confronted an alleged rapist was informed Tuesday that the Army has denied his appeal.

Sgt. 1st Class Charles Martland earlier this year was ordered discharged by Nov. 1. He has been fighting to stay in, but in an initial decision, the U.S. Army Human Resources Command told Martland that his appeal “does not meet the criteria” for an appeal.

“Consequently, your request for an appeal and continued service is disapproved,” the office wrote in a memo to Martland.

The memo was shared with FoxNews.com by the office of Rep. Duncan Hunter, R-Calif., who has advocated for Martland’s case. According to Hunter’s office, Martland learned of the decision Tuesday.

Sgt. Martland is a mensch.

Why, it was only yesterday that the then-Commander in Chief was promising a geopolitical utopia:

A liberated Iraq can show the power of freedom to transform that vital region, by bringing hope and progress into the lives of millions. America’s interests in security, and America’s belief in liberty, both lead in the same direction: to a free and peaceful Iraq.

September 27, 2015

Benedict Option as a Way of Life

Molly Worthen writes about “the rise of the moral minority,” her term for conservative Christians who rebel against the culture-wars-as-usual strategy. Excerpts:

Yet some evangelical elites … have not shifted leftward, but they disown both the legacy of the Moral Majority and the populist demagogy of Mr. Trump in favor of a softer, more sophisticated approach to activism. They note the shrinking ranks of American Christianity but say that evangelicals shouldn’t kick and scream. They should embrace their new role as a moral minority instead.

“We don’t see ourselves as a cultural majority,” Russell Moore, the president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, told me. “Change doesn’t come from a position of power, but a position of witness.” Dr. Moore assured me that when he brings this message to churches around the country, “most are responding well because they see what’s happening in the culture.” But he is disappointed that so many evangelicals favor Mr. Trump.

How do you convince evangelicals to temper their political ambitions? You teach them to rethink their own identity. “Our end goal is not a Christian America, either of the made-up past or the hoped-for future,” Dr. Moore writes in “Onward,” his manifesto for the moral minority. “Our end goal is the kingdom of Christ.”

Worthen highlights the work of my friends Gabe Lyons and Eric Metaxas, and the way their circles favor the word “winsome” to describe the kind of temperament they think Christians should bring to cultural engagement. I love Gabe and Eric, and I much prefer their way of being Christian — they love Jesus, but they’re not pissed off about it — than that of the more aggressive culture warriors on our side. But something rubs me the wrong way about the word “winsome” in this context. It’s not that winsomeness is a bad thing, but I fear that too many Christians think that being nice is going to make the other side like them. As I told the Q Ideas gathering this spring, in a speech that many of them did not like, you can be as winsome as you like as a conservative Christian who holds to traditional Christian teaching on sexuality, and they’re still going to hate you, because they think you are the moral equivalent of a racist. We should be firm but kind in our dealings with the world, not because it will improve our standing, but because it is the right thing to do.

On this same general topic, Laura Turner writes in The Atlantic about the Moral Minority — and considers the Benedict Option. Excerpts:

This call for societal withdrawal marks a new turn for American evangelical Christianity, which for several decades had been mostly aligned with the political right. Increasing support for gay marriage, the declining rates of marriage, and the rise of the “nones,” all seem to indicate waning evangelical influence on American culture. In the fight-or-flight response to feeling threatened, more and more Christians are taking (or at least talking about) the road out of Rome [Note: She’s not talking about Catholicism, but about Benedict of Nursia’s leaving post-imperial Rome to head to the forest to pray — RD]. They want to regroup, immerse themselves in communities that share their values, develop more robust theology, and emerge, in a sense, stronger than before.

In this way, the Benedict Option could be just the thing evangelicals need. With their public influence waning, withdrawing from the political conversation, at least in part, and adopting a strategy of re-entrenchment could help both fortify Christianity and engage the public. Certainly, things are starting to look bleak for evangelicals who remain in the public square. Recent efforts to defund Planned Parenthood via a Senate vote failed, and some evangelical leaders are disavowing the culture wars altogether.

On the other hand, it is difficult to influence society from a position of defeat. Those who follow the Benedict Option and create sealed-off Christian communities will find themselves frustrated in their attempts to influence not only politics but also art, literature, media, science—any areas shaped by meaningful public conversation. There may be room for lament, like there was around Obergefell, but the ability for the larger church to offer its prophetic voice to the culture would be damaged.

I appreciate the opportunity to clarify, once again, that I’m not in favor of creating “sealed-off Christian communities.” I don’t think that’s either possible or desirable. Rather, when I think of the Benedict Option, I think of creating stronger, thicker communities within which traditional Christian life can thrive. That will require some separation from the wider world, and the creation of de facto barriers. A Catholic school, for example, that wanted to form Catholic children according to orthodox Catholic teaching may want to exclude non-Catholic students, and to expect parents to participate more directly in their children’s education than is usual with parochial schools. But the way I see it, if we Christians are to be salt and light to the world, we have to first learn to be real Christians, not Moralistic Therapeutic Deists with a Christian-ish gloss.

That will require rebuilding a thick Christian culture in which we and future generations can be formed. To the extent that secular modernity dissolves and assimilates Christian belief and practice, we must stand against it, creating the institutions within which we can build resilience, and developing the personal and communal habits that build resilience. Ken Myers sends me these excerpts from sociologist of religion Steve Bruce’s 2002 book God Is Dead: Secularization in the West; they illuminate the kind of mindset we have to fight:

In brief, I see secularization as a social condition manifest in (a) the declining importance of religion for the operation of non-religious roles and institutions such as those of the state and the economy; (b) a decline in the social standing of religious roles and institutions; and (c) a decline in the extent to which people engage in religious practices, display beliefs of a religious kind, and conduct other aspects of their lives in a manner informed by such beliefs.

More Bruce:

Following Durkheim, [sociologist Bryan] Wilson argues that religion has its source in, and draws its strength from, the community. As the society rather than the community has increasingly become the locus of the individual’s life, so religion has been shorn of its functions. The church of the Middle Ages baptized, christened and confirmed children, married young adults, and buried the dead. Its calendar of services mapped onto the temporal order of the seasons. It celebrated and legitimated local life. In turn, it drew considerable plausibility from being frequently reaffirmed through the participation of the local community in its activities. In 1898 almost the entire population of my local village celebrated the successful end of the harvest by bringing tokens of their produce into the church. In 1998 a very small number of people in my village (only one of them a farmer) celebrated the Harvest festival by bringing to the church vegetables and tinned goods (many of foreign provenance) bought in the local branches of an international supermarket chain. In the first case the church provided a religious interpretation of an event of vital significance to the entire community. In the second, a small self-selecting group of Christians engaged in an act of dubious symbolic value. Instead of celebrating the harvest, the service thanked God for all his creation. In listing things for which we should be grateful, one hymn mentioned ‘jet planes refuelling in the sky’! By broadening the symbolism, the service solved the problem of relevance but at the cost of losing direct connection with the lives of those involved. When the total, all-embracing community of like-situated people working and playing together gives way to the dormitory town or suburb, there is little held in common left to celebrate.

The consequence of differentiation and societalization is that the plausibility of any single overarching moral and religious system declined, to be displaced by competing conceptions that, while they may have had much to say to privatized, individual experience, could have little connection to the performance of social roles or the operation of social systems. Religion retained subjective plausibility for some people, but lost its objective taken-for-grantedness. It was no longer a matter of necessity; it was a preference.

In sixteenth-century England, every significant event in the life cycle of the individual and the community was celebrated in church and given a religious gloss. Birth, marriage and death, and the passage of the agricultural seasons, because they were managed by the church, all reaffirmed the essentially Christian worldview of the people. The church’s techniques were used to bless the sick, sweeten the soil and increase animal productivity. Every significant act of testimony, every contract and every promise was reinforced by oaths sworn on the Bible and before God. But beyond the special events that saw the majority of the people in the parish troop into the church, a huge amount of credibility was given to the religious worldview simply through everyday social interaction. People commented on the weather by saying God be praised and on parting wished each other ‘God speed’ or ‘Goodbye’ (which we often forget is an abbreviation for ‘God be with you’).

The consequences of increasing diversity for the place of religion in the life of the state or even the local community are fairly obvious. Equally important but less often considered is the social-psychological consequence of increasing diversity: it calls into question the certainty that believers can accord their religion.

One more Bruce quote:

The clash of ideas between science and religion is less significant than the more subtle impact of naturalistic ways of thinking about the world. Science and technology have not made us atheists. Rather, the fundamental assumptions that underlie them, which we can summarily describe as ‘rationality’ — the material world as an amoral series of invariant relationships of cause and effect, the componentiality of objects, the reproducibility of actions, the expectation of constant change in our exploitation of the material world, the insistence on innovation — make us less likely than our forebears to entertain the notion of the divine.

It’s not that people cease to believe in God under secular modernity, Bruce maintains. Rather, religion ceases to be prominent in informing the social consciousness and cultural milieu of a people. It becomes a privatized thing, with diminishing force in shaping the lives of individuals and of the collective. Can anybody seriously claim that we aren’t there now?

I don’t believe the Benedict Option requires us to withdraw entirely from the public square (though I believe we will be steadily pushed out). But I do believe it requires us to abandon thinking that the point of being Christian is to “influence society” for the good. Consider again this passage from Worthen’s column:

“Our end goal is not a Christian America, either of the made-up past or the hoped-for future,” Dr. Moore writes in “Onward,” his manifesto for the moral minority. “Our end goal is the kingdom of Christ.”

Yes, this a thousand times. As an Orthodox priest and reader of this blog reminded me the other day, St. Benedict did not leave Rome for the forest with the goal of saving what was left of Roman civilization. He left because he needed to be in a place of quiet where he could hear the voice of God, and pray, and worship as he was called to do. All that followed — the founding of the Benedictine order, the writing of the Rule, and in the subsequent centuries, the spread of monasticism and the evangelization of western Europe — came because that one monk, Benedict of Nursia, put the kingdom of God first. Remember what Alasdair MacIntyre said:

A crucial turning point in that earlier history occurred when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium. What they set themselves to achieve instead—often not recognising fully what they were doing—was the construction of new forms of community within which the moral life could be sustained so that both morality and civility might survive the coming ages of barbarism and darkness.

It’s like this: I would like my children and my children’s children to grow up in a free, prosperous, democratic country. But it matters infinitely more to me that they hold on to the Christian faith. Better that they live in an unfree, poor, undemocratic country, but one in which their faith is strong, than a rich one that has forgotten God. The Benedict Option is not ultimately about saving civilization. It is about saving our faith, and cultivating it so that it can live robustly in future generations, despite what I am firmly convinced will be the coming ages of barbarism and darkness.

For us traditionally-inclined Christians, it is time for a Great Relearning of what we have forgotten in modernity. And for that, we are going to have to revisit the Fathers of the Church, and learn from the experience of how the early church formed disciples within a hostile culture. Here’s a 1998 interview with church historian Robert Louis Wilken, in which he talks about this very thing. Excerpts:

What are some of the lessons we can learn from the early church about evangelizing our culture today? For example, should we do apologetics today as the early church did?

A lot of early apologetics was not defense but simple explanation. In his First Apology, Justin Martyr gave an account of Christian worship. He also talked about baptism. He didn’t try only to establish a link to the larger culture or prove Christianity true. He also tried to tell people what Christians actually did in worship and what they believed.

Today I believe the most significant apologetic task is simply to tell people what we believe and do. We need to familiarize people with the stories in the Bible and to talk about the things that make Christianity distinctive. Many people are simply unaware of the basics of Christianity. They’re rejecting something they don’t know that much about.

But apologetics then and now has a limited role. We must speak what is true, but finally the appeal must be made to the heart, not the mind. We’re really leading people to change their love. To love something different. Love is what draws and holds people.

What about the tightly knit early Christian community—what can we learn from that?

I think that should be a main strategy of Christians today—build strong communities. The early church didn’t try to transform its culture by getting into arguments about whether the government should do this or that. As a small minority, it knew it would lose that battle; there were too many other forces at work. Instead it focused on building its own sense of community, and it let these communities be the leaven that would gradually transform culture.

How did the early church build their community?

It built a way of life. The church was not something that spoke to its culture; it was itself a culture and created a new Christian culture. There were appointed times when the community came together. There was a distinctive calendar, and each year the community rehearsed key Christian beliefs at certain times. There was church-wide charity to the surrounding community. There was clarity, and church discipline, regarding moral issues. All these things made up a wholesome community.

Did the church strive to be “user-friendly”?

Not at all—in fact, just the opposite.

One thing that made early Christian community especially strong was its stress on ritual. That there was something unique about Christian liturgy, especially the Eucharist. It was different from anything pagans had experienced.

The worship was architecturally different. The altar at a Greek temple was in front of the temple and represented that worship was a public event open to all. In Christian churches, the altar was inside. Worship was something the church gave one the right to enter into.

Furthermore, in Christian worship there was no bloody sacrifice. Prayers and hymns were taken out of the Bible, a book foreign to pagans. And then there was a sermon, an unusual feature in itself, with historically grounded talk of a dying and rising God.

Pagans entered a wholly different world than they were used to. Furthermore, it was difficult to join the early church, besides the social and cultural hurdles: the process for becoming a member took two years.

Do you think we ought to adopt this strategy today?

Yes. I think seeker-sensitive churches use a completely wrong strategy. A person who comes into a Christian church for the first time should feel out of place. He should feel this community engages in practices so important they take time to learn. The best thing we can do for “seekers” is to create an environment where newcomers feel they are missing something vital, that one has to be inculcated into this, and that it’s a discipline.

Few people grasp that today. But the early church grasped it very well.

Read the whole thing. For Christians who create within their own tradition — Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox — a Benedict Option, it will be above all a way of life that is about initiation into the kingdom of God, and a life of constant discipleship and formation in love, mercy, repentance, and traditional Christian living. If this means fewer of us get to participate in public life in late imperial America, well, so it does. That is not the most important thing.

After I explained to him what the Benedict Option was, Father Cassian Folsom, the prior of the Benedictine monastery in Norcia, told me that he thinks in the years to come, Christians who don’t take some form of the Benedict Option aren’t going to make it through the long darkness now upon the West. He’s right. It is a time for choosing, a time for preparation, and a time for un-learning and re-learning. After all, the real battle is not political, but spiritual.

I’ll end with these photos of the kind of Christians I hope we in the spiritually dessicated West can be. Here is a photo of my friend Father Silouan Thompson, a missionary Russian Orthodox priest in the Philippines. He is chrismating a new Filipino Christian, who was just baptized in the ocean:

Fr. Silouan writes on Facebook:

By our count 187 people were baptized in the ocean this morning [Saturday Sept 26] at Kiamba, Sarangani province. Fr Stanislav Rasputin and I baptized despite unusually boisterous waves. At times it felt like playing with a kennel full of 200-pound mastiffs: You get knocked down repeatedly :). One particularly strong wave took Fr Stanislav’s epitrahil (stole) right off his neck and washed it out to sea; we think it’s halfway to Malaysia by now.

Kiamba is in an area where the Moro Nationalist Liberation Front (Islamic secessionist group) is quite active, and a number of foreigners have been abducted this week by various groups of evildoers; so we were grateful for the escort the Philippine National Police provided for our sacrament and our procession from the church to the beach and back (even if their machine guns were a little strange to American eyes.)

One hundred and eighty-seven Filipinos received baptism in a single day — and they risked their lives at the hands of Islamic terrorists to do so! The Holy Spirit goes where He is wanted.

#LouisianaForTheWin

Part of my weekend travel: in the parking lot of the Best Stop in Scott, La., in the bright sunshine eating smoked boudin I just bought there. Love the look on the BVM’s face; she’s presiding over the parking lot. South Louisiana, man!

A Benedictine’s Life

Imagine my delight to see Father Cassian Folsom, the prior of the Benedictine monastery in Norcia, interviewed in today’s New York Times. Excerpt:

Imagine my delight to see Father Cassian Folsom, the prior of the Benedictine monastery in Norcia, interviewed in today’s New York Times. Excerpt:

READING Between liturgical prayer, Scripture reading, daily work and community activities, my time is very limited. The last time I read a novel was when I had to have a stem cell transplant in 2012 for multiple myeloma and had to be in isolation for four weeks. It’s too bad that it takes that much to get me to read a novel, but I read “The Red Horse,” by Eugenio Conti, a wonderful and moving story about Italian involvement in World War II told through the lives of people living in a small town in northern Italy.

LISTENING As monks, we live in the silence like fish live in water. But our liturgical prayer is all song, mostly chanting together. It’s usually alternating from one side of the choir to the other, so it’s kind of a dialogue. It’s for the glory of God, so you feel it’s something larger than yourself that you are caught up into. It’s a quite remarkable experience, in fact.

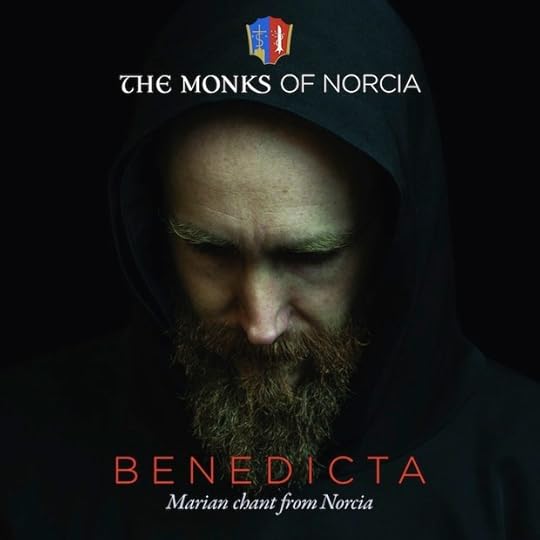

If you take a look at the article, you’ll see that they photographed him at the crypt altar that was part of St. Benedict’s fifth-century house. I’ve prayed in that very spot. It was incredibly moving. It really is hard for me to find enough superlatives to describe that monastery and its joyful, young, light-filled monks, who earlier this year released their first album of chant. Father Cassian is in his 60s, and he is much the oldest member of the community; he says in the NYT piece that the average age among them is 33. The Spirit is working powerfully among those men. Again and again I say unto you: if you are an unmarried Catholic man who sense a possible calling to the monastic life, get to Norcia as fast as you can and see if it’s for you. That’s a Benedict Option that some of you should consider.

Say, New Yorkers, on October 7, Ross Douthat will be speaking at a Manhattan event to benefit the monks of Norcia. Information here. They will also be serving beer brewed by the Norcia monks. You don’t want to miss this. Father Cassian will also be there to talk about the work they’re doing in the monastery. If you want to see the face of hope for the future, go meet Father Cassian and any of the brothers he will have brought with him.

The Sexy Pope Francis

Ross Douthat observes that Pope Francis has had a great trip to the US, and says it’s not an altogether bad thing if Francis revives the Religious Left:

A revitalized religious left, a Christianity that doesn’t feel like the province of a single political faction, would be a sign of religious vitality writ large. And I would far rather debate politics with Cornel West or the editors of Commonweal than with a liberalism that thinks it can impose meaning on a cosmos whose sound and fury signifies nothing on its own.

Me too. But Douthat says that religious liberalism is flagging in this country for serious reasons, among them its discomfort with supernaturalism, and the other “is religious liberalism’s urge to follow secular liberalism in embracing the sexual revolution and all its works — a move that promises renewal but rarely delivers, because it sells out far too much of scripture and tradition along the way.”

More:

The second tendency, though, is one that Francis has tacitly encouraged, by empowering clerics and theologians who seem to believe that Rome’s future lies in imitating the moribund Episcopal Church’s approach to sex, marriage and divorce.

How far to go with them is the question that awaits the pope in Rome this fall, and that hangs over the springtime for liberal Christianity his pontificate has nurtured.

How it’s answered, and what follows, will determine whether we’re watching something genuinely new and fresh emerge — or whether, after the cheering ends, the same winter that enveloped liberal Protestantism after the 1960s will claim Franciscan Catholicism as well.

Read the whole thing. That last paragraph brings to lines a few lines from the diary of the Orthodox priest Alexander Schmemann. A reader sent me this bit in which Fr. Schmemann mused on Pope John Paul II’s visit to NYC in 1979:

The Pope’s days in New York are accompanied by extreme excitement and rapture. What remains is that one can see something quite genuine (man’s longing for goodness) and something obviously connected with our civilization: television, “media,” etc. What worries me is this: this popularity will recede as soon as the pope concretely expresses his faith. Then the euphoria will end… And then will begin: “crucify him” and “we have no King, but Caesar…” — i.e., a return to the present. (Mark 15:13-14, John 19:15)

We’ll see what happens with Francis. Have to say I think his big Philadelphia speech about religious liberty was disappointing. Religious liberty is at serious risk in the emerging American order, but his speech was bland and safe. It was like, “America is a land of religious liberty. Religious liberty is important. You Americans should treasure it. Don’t forget the immigrants! Adios.” He didn’t say anything wrong, but he didn’t say much of anything at all. The religious liberty cause could have used a more forceful, direct, and specific speech from this popular Pope.

Anyway, back to Douthat’s point. Michael Pakaluk, a philosopher at Ave Maria University, has a piece up at First Things condemning what he calls “lifestyle ecumenism,” which he defines as “the view that Catholics should practice today a kind of ‘ecumenism’ towards persons in living arrangements other than marriage, such as cohabitation, common law marriage, and same-sex relationships.” This approach, which has been advocated by cardinals close to Francis, and which will be at issue in the October Synod, violates Catholic teaching, says Pakaluk. He makes his case, then concludes:

As a father of a large family, raising children in the difficult circumstances of the present culture in the US and Europe, I find the Cardinal’s [Christoph Schönborn’s] approach particularly dismaying. I want clear teaching from bishops, to back up my efforts with young persons; I want an unfashionable but needed reminder, in our time, of the imperilment of the soul and the reality of sin. In contrast, Lifestyle Evangelism looks like the rationalization of a bad outcome. The main task of the bishops, I conceive, is to teach the faith clearly and protect the flock from the trepidations of the Evil One. Our bishops in the 50 years since Humanae vitae have generally failed at these tasks in the area of sexual morality. Cohabitation and the hook-up culture do not “just happen.” Two generations of Catholic children who might have grown up living chastity and modesty have been lost, taken away by faulty Catholic school systems, inadequate catechesis, cowardly preaching, and an absence of a protective spirit by our pastors. The True Pastor goes so far to keep out the wolves that he lays down his life if necessary. Lifestyle Ecumenism strikes me as a shrug of the shoulders which says it’s a fact of life that wolves take the sheep.

Nobody can doubt that Pope Francis has had a spectacular trip here to the US. Even my Catholic friends who tend to be skeptical of his papacy and its priorities have been inspired by this papal pilgrimage. And why not? Francis is a rock star. But so was John Paul II, and that fact did not bring his flock back to the traditionalist Catholic teaching on sex and the family, which he never hesitated to preach. Now Francis is trying something different. We’ll see what happens. The experience of the Episcopalians and other Mainline Protestants doesn’t give much reason to hope.

September 26, 2015

The 2015 Mustard Greens Queen

Mrs. Sue Powell cooks better than you

I am genuinely thrilled to say that Mrs. Sue Powell is the Mustard Greens Queen of West Feliciana Parish for the fourth year in a row. I just learned this at midnight, and now I’m dying for a mess of mustards. Congratulations to Miss Sue!

I wonder if you have to come from the South to like greens. You have to soak cornbread in the pot liquor to get the full effect. I’m making myself really, really hungry right now…

UPDATE: Well, I couldn’t stand it. Midnight snack below: thawed-out jambalaya with habanero sauce and Tony Chachere’s. #LouisianaWinsAgain

Baby Irene’s Baptism

You readers who have followed the story of Baby Irene Harrington and her family will be pleased to learn that she became a Christian this morning. Her father baptized her. Many of you contributed to the GoFundMe account for the Harrington family, for which I once again thank you. Thanksgiving for generous contributions also goes to the congregation of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Catholic Church in St. Francisville, as well as to Father Frank Bass and his parishioners at St. Isidore Catholic parish and St. Pius X parish. No doubt many more people gave quietly, and their names are known only to the Harringtons, or to God alone. Whatever the case: thank you.

Irene was born with severe birth defects, and will require many surgeries and constant care. Her mother nearly died giving birth, requiring 31 units of blood during surgery. The hardships that this family are facing and will face are severe, but there was nothing today among us but joy and gratitude for new life. That, and Chantilly cake. Glory to God for all things!

‘A Traveler Unstuck From Place And Time’

This is so good, so good. But you have to know Herzog’s documentaries and his narration style to fully get the joke, but it’s enough to know that he is an angsty Teuton full of maximum existential heaviosity.

September 25, 2015

The Anti-Benedict Conspiracy

Catholic journalist Edward Pentin got his hands on a copy of the authorized — repeat, authorized — biography of retired Belgian cardinal Godfried Danneels. Blockbuster stuff in it, according to Pentin’s report. Excerpts:

At the launch of the book in Brussels this week, the cardinal said he was part of a secret club of cardinals opposed to Pope Benedict XVI.

He called it a “mafia” club that bore the name of St. Gallen. The group wanted a drastic reform of the Church, to make it “much more modern”, and for Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio to head it. The group, which also comprised Cardinal Walter Kasper and the late Jesuit Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, has been documented in Austen Ivereigh’s biography of Pope Francis, The Great Reformer.

Danneels has been bad news for a long time. Pentin again:

It was also revealed this week that he once wrote a letter to the Belgium government favoring same-sex “marriage” legislation because it ended discrimination against LGBT groups.

The cardinal is already known for having once advised the king of Belgium to sign an abortion law in 1990, for telling a victim of clerical sex abuse to keep quiet, and for refusing to forbid pornographic, “educational” materials being used in Belgian Catholic schools.

He also once said same-sex “marriage” was a “positive development,” although he has sought to distinguish such a union from the Church’s understanding of marriage.

The Italian Vaticanist Marco Tosatti writes (in Italian; I’ve modified the Google translation:

The election of Jorge Bergoglio was the result of secret meetings that cardinals and bishops, organized by Carlo Maria Martini, held for years in St. Gallen, Switzerland. This, according to Jürgen Mettepenningen et Karim Schelkens, authors of a newly published biography of the Belgian Cardinal Godfried Danneels, who calls the group of cardinals and bishops a “Mafia club”.

Danneels according to the authors, worked for years to prepare for the election of Pope Francis, which took place in 2013. Danneels, moreover, in a video recorded during the presentation of the book in Brussels, admits that he was part of a secret club of cardinals who opposed Joseph Ratzinger. Laughing, he calls it “a Mafia club that bore the name of St. Gallen”.

The group wanted a drastic reform of the Church, much more modern and current, with Jorge Bergoglio, Pope Francis, as its head. They got what they wanted. Besides Danneels and Martini, the group according to the book were part of the Dutch bishop Adriaan Van Luyn, the German cardinal Walter Kasper and Karl Lehman, the Italian Cardinal Achille Silvestrini and British Basil Hume, among others.

I underscore that this is not some secretly sourced claim, but it’s from an advance copy of Cardinal Danneels’ official biography, approved by himself.

This is the first confirmation of rumors that had been going around for years about Benedict being thwarted by a liberal conspiracy, one that eventually forced him out. These men — Danneels, Van Luyn, Kasper, Lehman, and Hume, at least — all preside over dying churches. And they killed the Benedict papacy. Danneels, you will note, was given by Francis a prominent place at next month’s Synod on the Family.

I am glad this came out now. The orthodox bishops and others going to the Synod now know what a nest of snakes they are working with, and how high up the corruption goes. Poor Pope Benedict. My heart breaks for that good man.

UPDATE: Apparently there has been a lot of talk i some circles about the “Team Bergoglio” affair since Austen Ivereigh’s book about Francis, The Great Reformer, came out late last year. Br. Alexis Bugnolo writes about it here, and again here.

Moralistic Therapeutic Papism?

Denny Burk, a Southern Baptist, was disappointed by Pope Francis’s speech to Congress. Excerpt:

The Pope didn’t speak prophetically but politically. The Pope spoke clearly and at length in support of liberal political priorities—climate change, immigration, abolishing the death penalty. He spoke vaguely and briefly (if at all) about the most contested social issues of our time—abortion, marriage, and religious liberty.

Well, I don’t see climate change or the death penalty as liberal theological priorities, certainly not within Catholicism. Immigration is also an important priority to Catholics, though I am less convinced than many Catholics are that there is a clearly Catholic theological mandate in favor of mass immigration. I am neither surprised nor bothered that the Pope spoke on these things. But I agree with Burk that it is shocking that the Pope barely talked about these other things.

On abortion, given the Planned Parenthood undercover videos, and given that defunding Planned Parenthood is about to come up in front of the Congress, and especially given that there are many Catholic Democrats who are planning to vote against removing government funding from the very organization that slaughters these children and sells their body parts, it is bizarre that Francis didn’t speak more explicitly about abortion.

Burk also notes that Francis didn’t get into the same-sex marriage issue explicitly, or religious liberty, beyond vague statements. This too is mystifying, given the recent changes in US culture, and given how the freedom of the Church he leads to run its own institutions according to what Catholics believe to be the truth is very much at issue in our country. There he was speaking before the United States Congress, and barely mentioned this. Again, it’s inexplicable, given the forum, and given the very real attacks, current and future, on Catholic teaching and religious liberty coming from US courts and political liberals.

The conservative Catholic Robert Royal is much happier with what Francis said than the Southern Baptist Burk is, but there is this:

Inexplicably, at the same time, the Holy Father – in his address to the bishops – warned them about being harsh, about failing to offer the people of God that attractive light that is the Gospel of Jesus Himself. Situations around the world differ, to be sure, and the pope may have some concrete experience of his own in mind. But those of us who consider ourselves unshakeable friends, and supporters, of the papacy – and who have knocked about in various corners of the world – have a fair bit of difficulty in identifying who, exactly, the Holy Father thinks he is speaking to, when he frets about harshness and rigidity, especially when Catholicism is under assault, even in the developed nations of the world.

Far more people, in our experience anno Domini 2015, in many parts of the world, are less troubled about a Church that is too judgmental than a Church that has lost its way – and has nothing distinctive to say to the secular world. If the pope wants to say something truly revolutionary in America, he might propose to us that Christianity might be something more than openness, tolerance, kindness. The secular world doesn’t need Christianity to appreciate that. So exactly who do we think we are speaking to?

I love how Francis confounds both the American left and the American right. In that he is being Catholic, given that Catholicism does not line up squarely with either political ideology. And unlike my Evangelical friend Denny Burk, I don’t mind that the Pope gave a political speech in a political forum. What I find hard to explain is why the Pope barely paid attention to the most important political issue facing his American flock: the way the Sexual Revolution is beginning to impact religious liberty for those individuals and institutions which, like the Catholic Church (at least officially), oppose it.

If one draws the impression that Pope Francis doesn’t really care about these things, one could hardly be blamed. I am thinking right now about the Catholic high school religion teacher who wrote to me after Francis’s famous “Who am I to judge?” remark regarding homosexuality. He said that even though the pope wasn’t turning away from Catholic teaching, that’s how it was received by his students, who said, “Hey, the Pope has no problem with it.” So there’s that.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 502 followers