Brad Taylor's Blog, page 2

January 2, 2020

Let’s Play Iran’s Game, Not our Own.

The world woke up yesterday to a bunch of maniacs chanting “Death to America” outside the US Embassy in Iraq, and given what I’ve seen on TV, with references to Benghazi and the seizure of the US embassy in Iran in 1979, I’m pretty sure that the average American has no hope of knowing what’s actually happening. Watching the news, you’d think that Iraq is either hell bent on kicking us out or killing us, but that’s not the case. Unfortunately, the problem set is more complex, involving more than just Iraq, and it starts in 2011 (Okay, it REALLY starts in 1991 with the original Gulf War, but for today’s crisis, it’s 2011. Yes, I know that if we hadn’t invaded in 2003, we wouldn’t be here, but we have to start somewhere, and it is what it is.) Buckle up. It’s a little bit of a story, but it’s really not that hard to understand, which makes me wonder what all the talking heads do for a living, because they’re sure as shit missing the narrative. In a nutshell: We want to deter Iran without losing our allies in Iraq – and from what I can see –we’re making some mistakes.

In 2011 Barrack Obama ceased all combat activities in Iraq, pulling out United States troops and leaving a giant vacuum of power that Iran rushed to fill. The Shia block in the government, under the sway of Iran, became very heavy handed and crushed Sunni protests over petty grievances in the Al Anbar province. The Sunni protests grew, and the Shia-dominated government became more oppressive. Enter ISIS, a Sunni extremist group. The Sunnis in Al Anbar didn’t necessarily side with ISIS, but they were more than willing to let them run amok because they were targeting the Shia government. The enemy of my enemy, and all that. ISIS became an absolute monster which took over Mosul, the second largest city in Iraq, and there were fears it was going to take Baghdad. While the United States dithered about what to do, Iran saw an opportunity and stepped into the breach, training and equipping militias to fight ISIS. Militias that to this day are completely beholden to Iran for their very existence.

During the ISIS campaign we sided with the militias because, yet again, the enemy of my enemy… The militias fought well, but there was always tension because of Iran’s control. After ISIS was defeated, the Iraqi government had a problem, namely, what to do with the militias Iran had formed, trained, and equipped? They weren’t part of the national security structure of the Iraqi state, and they were most definitely under the sway of Iran. The Iraqi government decided to try and coopt them, putting the militias officially under the national security structure, which is ostensibly where they remain today – but they don’t listen to the Iraqi security establishment. Most listen to Iran, but not all. There is a faction of Iraqi nationalists who have their own militia and who don’t like Iran calling the shots, which is a fracture that could cause the collapse of the entire Iraqi government.

Fast forward to today, and our maximum pressure campaign on Iran through sanctions. We’re basically slowly squeezing the life out of Iran, which has caused strife in Iran and sparked protests on its home turf. As I explained in another blog, though, Iran is not impotent. It’s struck the oil fields of Saudi Arabia, put mines on tankers in the straits of Hormuz, and shot down a US Global Hawk drone. Iran has plenty of options available to it to cause mischief, and it’s using them in Iraq.

The regime has had a malign influence on Iraqi politics since we left in 2011, and because of it, the grass roots of the Iraqi population are sick of Iran. They have started to protest about Iranian influence in Iraqi politics, to the point that it’s making noise on the world stage. Iran cannot tolerate this. It cannot be the “bad guy”. At first, it directed the PMU militias to attack the protestors – using the strong-arm tactics it executed in it’s own country – which it did, but that only exacerbated the anti-Iranian sentiment. Iran decided that it needed something else, and it turned to America to provide it. Using the Hezbollah militias in Iraq, it has attacked U.S. bases more than eleven times in the past few months—all of the attacks designed for one thing: A kinetic response.

Finally, Iran managed to kill an American contractor and wound four other service members, and sure enough, we launched airstrikes against the militias inside Iraq, which was an incredible unforced error. Now, the same protesters who were in Tahir Square denouncing Iran yesterday, are denouncing American imperialism today. In no way did our airstrikes deter any Iranian attacks against our bases, but they most likely turned the average Iraqi against us. We opine on the news about using airstrikes as a just response to the proxy force’s rocket attacks, and in a vacuum, it is, but in the greater scope of the political environment, it is a potential disaster in the making.

To put it in context, we had a Saudi national pull out a pistol and kill several people in pilot training at Pensacola, Florida a couple of months ago. The outcry was tremendous about canceling all foreign training and getting rid of all Saudi nationals. Now imagine if that same Saudi national got in an F 15 and flew across the United States blowing things up?

That’s what Iraq saw.

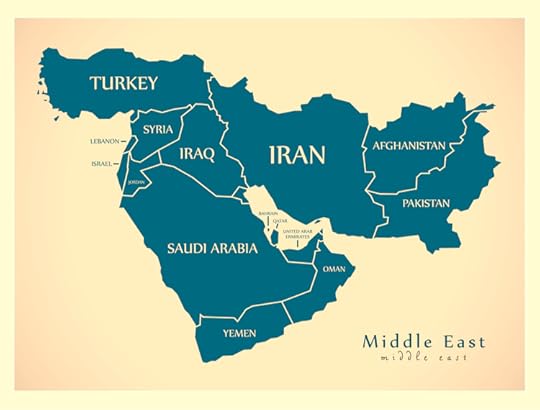

Make no mistake, Iran wants us out of Iraq. We are the one thing stopping them from attaining complete hegemonic control from their borders to the levant. The regime wants a land bridge from Iran to Syria, whereby it can reinforce Hezbollah in Lebanon and own the entire arc of the Middle East, and the only thing preventing that is United States influence inside Iraq. It can’t defeat us force-on-force militarily, but the regime most certainly can asymmetrically. If it can get the Iraqi population to hate us – to demand we leave – it wins, which is exactly its strategy.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of leverage in this fight. The PMU’s can attack us with impunity, but if we strike back in Iraq, we engender the very hatred we want to avoid. We have a dilemma of getting punched in the face repeatedly or getting vilified for defending ourselves. It’s a Hobson’s choice that is too narrow in scope. Iran is attacking us asymmetrically, and we choose to fight back in its chosen arena, which is a mistake. We’re looking at the wrong problem set.

Iran is behind the Hezbollah militia attacks, but we went after the direct cause of the attack – the Hezbollah militia in both Iraq and Syria, which played right into Iran’s hands.

As I’ve said before in other blogs, deterrence theory isn’t that complicated. You must threaten something the enemy holds more valuable than the action you’re trying to deter. Threatening the Hezbollah Iraqi militia doesn’t do a damn thing against Iran. It could care less how many of them we kill, because we’re playing into its “imperialist American” narrative. Far from deterring them, we’re helping Iran’s cause. If they want to play the proxy game, then so should we.

We need to threaten what they hold dear, and we don’t need to do it in an overt way. No huge proclamations on twitter, no grand bluster of fire and fury. This is a back-door war, and we should fight it just like Iran. If it conducts rocket attacks against our bases, injuring Americans – which will happen again –what should we do? Strike more militia targets? No. We should attack the leadership in Iran. I don’t mean actually assassinate anyone, because the protests there are doing exactly what we want and a strike such as this could be counter-productive if we cheer about it, but something close – in baseball terms, give them some chin music from the pitcher. Let them know we aren’t messing around, but do it like Israel – without saying a word.

They’ll get the message. You attack us in Iraq through your proxies, and we aren’t coming after the militias. We’re coming after YOU. The next missile is coming through the roof, and we don’t need to get on the news to do that. Let the strike speak for itself. In fact, don’t even acknowledge the strike. Use Iran’s own playbook against it. Was it Israel? Saudi Arabia? The United States? Who knows? But IRAN will know. Turn the whole problem set upside down, like they’re doing to us. Rockets hit our bases in Iraq? Iran says, “That’s not us…I don’t know why the US is so mad. Maybe it’s just because they’re the evil empire.” Really? Turnabout is fair play. Cruise missiles hit the center of Tehran and we say, “What happened? That wasn’t us. Maybe it’s somebody who doesn’t like what Iran is doing. Maybe…just maybe…whoever it is is serious about Iran’s malfeasance.”

In the end, we make a mistake trying to fight force-on-force in an asymmetric battle. It’s not the militias we’re fighting, it’s Iran – and if we want to send a message to them, we need to send it to THEM, not their proxies in Iraq.

The post Let’s Play Iran’s Game, Not our Own. appeared first on Brad Taylor.

June 27, 2019

War with Iran…Three Differences and One Similarity

Iran has come to the forefront of political and military discourse in the last few weeks, and lost in the shuffle of hyperbolic political statements is exactly what a war with Iran would mean and what would be required from the American public and the military. Too often – as I have learned from personal experience – elected officials promise a quick and easy war when it most decidedly will not be either quick or easy.

Make no mistake, Iran is a malignant actor on the world stage and I fully believe it was both responsible for the planting of bombs on two cargo ships in the Hormuz strait and shooting down our drone in international airspace, luring the US closer to a war. To that end, I thought it would be instructive to show just how different this war would be from any of the near-term conflicts the U.S. has conducted. I heard Senator Tom Cotton say that it would be over in two strikes, causing my jaw to literally fall open. I’m not sure what Kool Aid he was drinking, but I was shocked to see a former army soldier, who participated in both the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, reduce a war in Iran to a platitude. Quite simply, his rosy prediction is woefully inadequate.

Beyond the politics, here are three differences and one similarity in an Iran war vs. our past recent wars:

Number One: Iran is a homogenous country. They are Persian, and devoutly proud of that fact. In both Iraq and Afghanistan, at the most we had ambivalence to the power structure, and at the worst, outright hatred. Iraq was a predominately Shia country ruled by an iron fist from a Sunni minority under Saddam Hussein. Thrown on top of that was a Kurdish population who had been literally gassed in an attempt at genocide. Despite all those fractures, we saw how Iraq played out. None of that will come into play in Iran. They will rally around the Iranian flag like there is no tomorrow, using the entire country to fight our advance. Anyone who says there is some subset of the population who would welcome our invasion has not studied this problem set. Yes, they have had protests, like the Green Revolution, but that doesn’t mean they want a foreign country to invade. While many in the country despise the mullahs, that doesn’t translate into open arms for the United States to conduct regime change. To put it in plain language, we had the “pussy hat” protests when Trump was inaugurated. Do you believe that all of those women would cheer on a North Korean invasion a la “Red Dawn”? (Just go with it) No. As much as they hate Trump, they wouldn’t welcome a North Korean takeover to get rid of him. They wouldn’t, because at the end of the day, they’re American more than they’re a political party, and it’s the same with Iran. Nobody is going to welcome us in this fight.

Number Two: This would be the first war where cyber would play a significant role. Against the Taliban it was a non-starter. They didn’t want anyone to read, much less work a computer. What about Iraq? Saddam would have liked to use it, but it was in the early days of the internet and he hadn’t built the groundwork. Iran has. We’ve already seen tit-for-tat cyber attacks from both sides. If we were to invade Iran, and regime change were on the line for the ruling class, the gloves will come off, and cyber will become a whole new front. The U.S. should expect everything from gas station outages to complete power failures to hospital ransomware attacks to corrupted Wallstreet banking transactions. Iran has learned a great deal about cyber since our own attack on them using the STUXNET virus, and has dedicated significant resources to developing a reciprocal capability. If we go to war with Iran, expect cyber to be unleashed in a wholesale manner for the first time in modern warfare.

Number Three: This will be a multi-front war. While both Iraq and Afghanistan had hints of a greater theater—from Syrian rat lines for foreign fighters entering Iraq to Taliban/Al Qaeda fighters hiding out in the FATA frontier lands of Pakistan—neither of those governments could count on any allies to help them in their fight, nor could they project force outside of their own borders.

The Taliban is basically a cult, and everyone in the Middle East hated Saddam Hussein. That is not true with Iran. It has a devoted base that stretches from South America to the Gaza Strip. We have arrested multiple Hezbollah “sleeper cells” in the United States, and the IRGC Qods force controls Hamas in Palestine, Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, and almost all of the Popular Mobilization Forces in Iraq. Asserting that the U.S. could attack Iran in isolation – destroying it in two strikes according to Senator Cotton – is delusional. While I don’t believe Iran will unleash worldwide mischief based on a limited U.S. attack, make no mistake, if it feels its regime is threatened – and thus they have nothing left to lose – it most certainly will retaliate.

Besides the United States, its two biggest opponents – and the two cheering on a U.S. intervention – are the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Israel. Iran would attack both countries on two separate fronts for each. For KSA, Iran will unleash the Houthis in Yemen, encroaching inside Saudi Arabia proper from its southern border and tying down its forces to protect a southern flank. At the same time, it’ll instigate a destabilizing effort in Bahrain – another Sunni controlled country with a Shia majority. KSA has already invaded that country once to ensure the Sunnis remained in control, and it doesn’t require a crystal ball to see that Iran will leverage that unrest again. And, by the way, Bahrain is the home of our own Fifth Fleet, a tempting target

In Israel it’s easier. Iran will use Hezbollah in Syria and Lebanon to the north, and Hamas in the west from the Gaza Strip, to pin down the Israeli Defense Forces and force them to focus on their own survival versus helping us against Iran. At the same time, Iran will cause havoc with shipping in the Hormuz Straight, to inflict maximum pain on our European allies to pressure us to quit fighting.

U.S. troops in the region would provide another front, which Iran will attack. Without belaboring the point, while the US seeks to force its will on Iran, our forces will be attacked in Iraq through the PMF militias owned by Iran, which will give us a choice: Either start another war there, or simply leave Iraq, giving Iran full influence. We won’t want to do the former, but we can’t do the latter because we will need the bases in Iraq to conduct a campaign against Iran. This would lead to fighting in two different theaters against two different opponents.

Expect Iran to also open an “eastern front” inside Afghanistan when we try to use that country as a lily pad for force projection, sabotaging our fragile quest for a peace deal in that country and forcing us to use three-to-one manpower simply to protect our bases. Worst case, when the Iranian regime feels truly threatened, they’ll conduct overt attacks in our own heartland. Imagine three suicide bombers in three different states setting themselves off at a middle school, slaughtering eight year olds. The panic would be unprecedented – and all of the above would be without overt Iranian fingerprints. Neither Iraq nor Afghanistan had that capability, but make no mistake – Iran does. The bottom line is the United States has had a monopoly on violence for decades, but we haven’t attempted a kinetic operation since World War II where the opponent has multiple options to counter us.

Finally, the one similarity for both Iran and our other recent wars: At the end of the day, we would prevail in a conflict with the theocratic regime. It might be costly, but despite all of its asymmetric advantages, Iran would fall to our military might. When that occurs, we’ll be back where we were in 2002 in Afghanistan and 2004 in Iraq. Namely, what do we do now? Assuming we can bomb Iran into submission and then leave will not give us the solution we are attempting to accomplish. As the failed policy in Libya has starkly shown, getting rid of a regime is only half of the equation. The other half is what comes after, and this is where we’re really in a quandary. We have absolutely no capacity to install a new government that is more in line with our goals, and absolutely no allies who could help. There isn’t a Thomas Jefferson waiting in the wings to take the reins and start a democracy. Who’s going to do it? KSA? Israel? No, we’ll end up with the IRGC hiding in the population. If we’ve learned anything from our recent conflicts it’s precisely that we’re really good at breaking things, but challenged when rebuilding. But as I said about Libya in multiple blogs while that fiasco was occurring, that is precisely what will need to occur. Libya is now a terrorist mecca, where the armories were looted, which caused the downward spiral of Mali and directly led to the deaths of four US SOF in Niger. If we aren’t thinking about an endgame in Iran, we’ll get the same result.

In the end, bravado-laden comments from our elected leaders may play well on twitter, but somebody is going to have to pick up a rifle and execute, and before that happens, we should make a clear-eyed assessment of what we’re facing. We didn’t do that in Iraq or Libya, and the world is worse off because of it. If attacking Iran is necessary, then by all means, let’s do it, but let’s be honest with the American people about what that would entail. We should at least use our historical knowledge to avoid the myopia of the past, and not lead with rosy predictions of two strikes and we’re done.

The post War with Iran…Three Differences and One Similarity appeared first on Brad Taylor.

April 17, 2019

Designating the IRGC a terrorist organization? Not a good idea.

Last week, the Trump administration designated the entire Iranian Revolutionary Guard’s Corps (IRGC) as a terrorist group, which finally took effect yesterday. I’d hoped that saner heads would prevail in the meantime. While on the surface that seems like the right move, it’s replete with negative ancillary effects that far outweigh any positive ones.

Right up front, I’ll say that this idea didn’t arise from just the Trump administration. I remember writing The Widow’s Strike in 2013, where Pike goes against a Qods Force IRGC officer and he’s stymied because the Taskforce didn’t have authority to target him, as he wasn’t part of an organization designated a FTO – a Foreign Terrorist Organization. In the story, the Oversight Council acquiesced to the adventure because the designation was coming – and it was, by news reports. Both George Bush and Barrack Obama considered changing its designation, and both pulled back from the brink based on sound reasoning.

The word “Terrorism” has a finite meaning, and by designating them as such, we dilute what we want to achieve. Terrorism is a sub-state phenomenon. In our own United States Code, state actors cannot, by definition, be terrorists. That doesn’t mean they are good or just, but words have meaning. There’s a reason we don’t arrest a bank robber who killed someone in a robbery, and then charge him with terrorism. Did he terrorize the people in the bank? Yes. But he isn’t a terrorist. There’s another word for him in our judicial system: Murderer.

In the same vein, the IRGC isn’t conducting terrorist attacks. Does it support terrorism? Yes. Does it fund terrorism? Yes. But, it’s also a state organ. And, conveniently, we have a designation for that, and Iran has been included in it for decades: State Sponsor of Terrorism.

That is what the IRGC is doing, and by designating it as a terrorist group instead of a sponsor of terrorism, we’ve diluted the meaning of the term, which ultimately will benefit our enemies. For example, we are currently, training and advising a Kurdish force in Syria to wrap up operations against ISIS – a true terrorist group. The Kurds we’re helping have been designated a terrorist organization by Turkey. By advising them, much like the IRGC does with Hezbollah, we’ve now given Turkey every right to claim that we are terrorists. I know that is far-fetched, but just yesterday, Iran did a tit-for-tat and its parliament designated everyone working with US CENTCOM as terrorists.

Beyond the sparring over words, there’s a reason we’ve always relegated the term to sub-state groups, and it’s precisely to prevent unscrupulous actors at the UN, screaming about “terrorism” from the US – or from Israel. It’s going to be difficult to defend Israeli actions when it’s attacked by partisans in the UN by saying, “terrorists aren’t states” when we just designated a state as terrorists. Even greater, how do we defend ourselves against unjust accusations of “terrorism” when we’ve given up the very meaning of the word?

The Qods force – the IRGC external branch that conducts support for terrorism – has already been designated a terrorist group. Iran itself has been designated a State Sponsor of Terrorism for decades, and all of those designations have repercussions in the form of sanctions. Designating the Iranian Army as a terrorist group does not increase the existing sanctions. All it’s accomplished is to make it easier for the word “terrorist” to be used by others, and hamper our ability to operate around the globe.

By federal law, because the IRGC is now designated as a terrorist group, nobody in our government can interact with anyone who tangentially associates with the IRGC. On the margins, there are some benefits – for instance, Instagram and other social media have dropped all IRGC related accounts to keep out of federal crosshairs – but on the main, it makes it harder to operate.

A perfect example is Hezbollah. Whether we like it or not, Hezbollah, which controls 40% of Lebanon’s parliament, is a legitimate political party in Lebanon. Hezbollah deals directly with the IRGC. Will we now break off all contact with Lebanon because its government has a political party that works with the IRGC?

More concretely, we’re still fighting ISIS in Iraq. The Iraqi military is working hand in glove with both the IRGC and us. Should our US military not coordinate with the Iraqi military since the Iraqis are working with the IRGC too? Actually, it’s not a “should” question. They literally can’t now. The end result is the US will lose moreinfluence in Iraq to Iran, a self-defeating event for negligible gains. I could continue with one example after another of international ties that could now be threatened as an ancillary affect of this new designation.

It just makes no sense.

In the end, while it may make some people happy to finally get the designation they’ve been pushing for years, putting the IRGC on the foreign terrorist organization list will do nothing more than muddy the waters of international designations and make our work fighting true non-state terrorists that much harder. Words have meaning, and while designating IRGC as a terrorist organization may sound good, it’s not likely to help our security.

The post Designating the IRGC a terrorist organization? Not a good idea. appeared first on Brad Taylor.

January 30, 2019

No, We Aren’t Invading Venezuela with 5,000 Troops

At a recent press conference, National Security Advisor John Bolton was photographed holding a notepad. Inquisitive people zoomed in on the writing, and saw, “5,000 troops to Colombia”. At that point, the original curiosity disappeared, and every news agency in the world proclaimed that the United States was preparing to invade Venezuela to oust the current president. I kept waiting for someone –anyone- to discuss the statement logically, but so far, I haven’t seen it. Every headline refers to “all options on the table” and the fact that the administration isn’t discussing the note at all.

Up front, I’ll state that I’m not read-on to any planning SOUTHCOM or the DOD is undertaking for Venezuela, but analyzing the available facts, I’m fairly certain what the note indicates.

First, if you haven’t been keeping up with the news, Venezuela is falling apart. It’s experiencing massive protests, and has a president that the United States (and a host of other countries around the globe) states is illegitimate. Second, because of our spat with President Maduro, he has demanded that all of our diplomats leave the country. In turn, we said, “Nope. Not happening. You can’t make us leave.” So where does that leave us?

Militarily effecting change in Venezuela would require significantly greater manpower than 5,000 troops. The thought is ludicrous. We invaded Iraq with nearly 200,000 troops. No, 5,000 isn’t enough to effect regime change, but it IS enough to conduct a forcible entry and create a lodgment inside Venezuela for a Noncombatant Evacuation Operation – or NEO – and that’s what the note most likely indicates. DOD and SOUTHCOM are simply planning for an eventuality that the United States may need to evacuate our embassy and any other AMCITS caught in the crossfire if Venezuela completely falls apart.

Such operations are an inherent task, and have been conducted multiple times over the years. I myself staged in Utapao, Thailand in 1997 because of a coup in Cambodia. Called Operation Bevel Edge, our mission wasn’t to intervene in the regime’s troubles, but to evacuate AMCITS under threat. We never executed.

Given the troubles occurring in Venezuela – and given our complete inability to evacuate anyone from Benghazi, Libya – DOD sees it as only prudent to prepare for such a contingency. You can be damn sure they don’t want a repeat of Benghazi. As for Colombia, a staging place close to the crisis site provides flexibility, allowing, among other things, immediate medical care, contingency planning for unforeseen events, and the processing of evacuees within the footprint of the operational area for orderly flights back to the United States. It’s precisely why Bevel Edge staged in Thailand.

Why won’t anyone just come out and say that? Because it sends a signal that can be read a myriad of different ways – and we don’t want to signal anything. All we want to do is prepare. Announcing that we’re sending 5,000 troops to Colombia because we’re sure that the end is near for Venezuela may start a chain reaction. Other countries may take our planning as fact, and rush to evacuate their own people and create a self-fulfilling prophecy that causes unnecessary chaos. It could also be inadvertently viewed by the Venezuelan government as camouflage for the very thing the press is breathlessly predicting. Either endstate is not something the US wants to project, so the administration is falling back on, “Nothing to see here. Move along. Sorry that picture was taken.”

I have no idea why John Bolton allowed that note to be seen, but one thing is for sure: We aren’t invading Venezuela from Colombia with only 5,000 troops.

The post No, We Aren’t Invading Venezuela with 5,000 Troops appeared first on Brad Taylor.

November 26, 2018

A Realpolitik Look at a Moral Conundrum

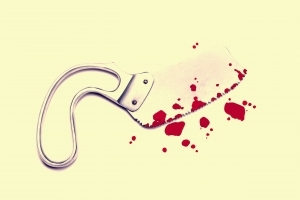

The savage murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in a Saudi consulate located in Turkey, followed by his dismemberment by bone saw, has generated worldwide horror and headlines, mostly centered on whether the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed bin Salman (known as MBS for short), had directly ordered his killing.

The argument in the United States has split along moralistic and realistic lines, with the moral side stating that a state-sanctioned murder must be confronted, no matter how powerful the man who ordered it. The realist side states that confronting an ally as important as KSA would be like punching ourselves in the face. In effect, one man’s life – no matter how despicable and heinous the demise – is not worth the risk to our geopolitical interests.

In the words of Eric Trump, President Donald Trump’s son, “You cannot be executing journalists or anybody else,” Trump said. “[But] what are you going to do? You’re going to take [America’s history of trade and agreements with Saudi Arabia] and you’re going to throw all of that away?”

President Trump agrees. In a remarkable statement, he projects that it is irrelevant whether MBS had a hand in the killing or not – our relationship with KSA is simply too big to fail.

It is realpolitik at its most extreme. According to Trump, the Kingdom’s purchase of American-made weapons, its alliance against Iran, and its outsized control of the global oil markets take precedence over any death or transgression KSA may execute.

The statement made the morally driven side of the debate howl, but I will submit that the two are not diametrically opposed. Realpolitik is politics based on practical objectives vice any ideological or ethical considerations – and President Trump’s “America First” is direct reflection of that, but his considerations are ephemeral and short-term. True realpolitik would look at the long-term implications of the current engagement with KSA, and in so doing, would see that turning a blind eye to the murder is not in our national interest, regardless of current arms sales or an alliance against Iran.

This is not the first time the Unites States has ignored its own moral code in the Middle East for what was perceived as strategic national interests. We gave one country a blank check for armaments, selling it more arms than any other country as a bulwark against the Soviet Union in the region even as its ruler was a brutal, sadistic dictator. No matter how heinous the ruler acted, we propped him up, generating enormous hatred. The country was Iran, and the ruler, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was overthrown by his own people in 1979, forming the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The first paragraph of President Trump’s statement has nothing to do with KSA, instead it details the crimes of the Islamic Republic of Iran, ending with this quote:

“Iran states openly, and with great force, “Death to America!” and “Death to Israel!” Iran is considered “the world’s leading sponsor of terror.”

Am I the only one who finds it ironic that we are now turning a blind eye to Saudi Arabia’s vicious transgressions so that it can help us confront Iran when it was exactly that sort of policy which led to the current animosity between the US and Iran? This isn’t the only example of such a policy eventually leading to disaster. Once Iran became a threat, after the fall of the Shah, we began to arm and help another dictator, ignoring his blatant savagery, because of his willingness to confront the Persian regime.

This time it was Saddam Hussein, and we continued to help him even after he used chemical weapons, shipping arms and providing intelligence during the Iran/Iraq war. He became so emboldened with our willingness to look away that he miscalculated and invaded Kuwait – using weapons we’d facilitated – leading to the first Gulf War and the current intractable mess.

This isn’t the first indication that MBS is a thug, it’s just the most blatant. He’s arrested anyone who opposes him in KSA, practically kidnapped the prime minister of Lebanon, holding him hostage until he agreed to resign, instigated a blockade of Qatar, continues a devastating war in Yemen – creating the greatest humanitarian crisis since WW II – and has generally acted as a despot as he’s consolidated the levers of power in the kingdom. Yes, he’s an ally now, but continuing to ignore his savagery will embolden not only him, but others on the world stage, and will likely end in failure. Hopefully, not with the entire country of Saudi Arabia spilling into the streets chanting “Death to America”.

Throughout our history, whenever we ignore the words in our own declaration of independence for short-term gains, we have ended up with long-term pain. Beyond the moral imperatives inherent in stopping brutal behavior, there is a reason we should strive to be, in President Reagan’s words, the “shining city on the hill” for the world. It’s because it’s in the best interest of the United States of America.

That’s true realpolitik.

The post A Realpolitik Look at a Moral Conundrum appeared first on Brad Taylor.

June 12, 2018

Five Fast Facts from the Singapore Summit

The summit in Singapore between the United States and the DPRK is over, and there is a lot of discussion in the press, to say the least. Here are five takeaways that I saw:

The word “historic” has been used quite a bit about the meeting between Kim Jung Un and President Trump, but truly, the only thing historic about it was that the president of the United States attended. Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama all had a standing invitation to meet with their respective counterpart in the DPRK and all refused because they didn’t want to legitimize the regime. Trump decided it was time for something different. He may be right, but the results of this meeting were neither historic nor groundbreaking. Everything stated has been said before, stretching back decades. The first bilateral meeting between the United States and North Korea occurred in 1993, and the statement produced after that meeting reads pretty much like the statement from last night, substituting the words “nuclear-free Korean peninsula” for “denuclearization”. The 2005 six-party talks discussed “security assurances” for the DPRK along with a much stronger wording of denuclearization. Saying more was gained at this meeting than ever before is simply not true. In the end, the fact remains that we’ve been here before. This fact doesn’t make the effort futile – and I applaud the attempt – but we shouldn’t be hyperbolic about what was accomplished. Right now, Kim Jung Un finally achieved the legitimacy that both his father and grandfather failed to earn while they were in charge. It remains to be seen if Trump’s gamble will pay off.

Trump has declared that all sanctions will remain in place, which is a good thing, but the ink hadn’t dried on the page of the joint statement before China began crowing that it was unprecedented and that the United Nations needs to begin removing sanctions as a show of good will toward the DPRK’s agreement to abide by UN resolutions.That is something to watch, because the United States can declare sanctions will remain in place, but if China disagrees, the sanctions are toothless. We don’t do business with the DPRK – but China does, and if they allow goods and services to flow, the sanctions are just words on a page. My analysis is that China and the DPRK talked about this in advance, and had already agreed to state that – no matter what happened – it was a huge success and it was time for sanctions to end.

Surprising everyone – to include US Forces Korea and South Korea – Trump stated he was ending joint war-games on the peninsula because they were too expensive and provocative. In effect, he’s given up security for some unnamed concession in the future. Yes, they are expensive, but so is Bright Star in Egypt, Cobra Gold in Thailand, Flintlock in Africa, and the Black Sea Rotational Force in Poland. We don’t conduct exercises for show, we do them for interoperability, and we just gave that away for little in return. The truth is the money spent has a much bigger impact for the DPRK, because every time we have an exercise, they duplicate it in a show of force, which is something they can’t afford. It drains the DPRK piggy bank much more than ours, and looking at this as some individual transactional approach is misguided. If Reagan had looked at costs alone, the SDI initiative would never have come about, and with it, the bankruptcy of the Soviet Union as they tried to match it. Now, if we attempt to bring the exercises back, the DPRK will scream that we were dishonest, and we’ll end up right back where we were with twitter tirades and DPRK “dotard” statements. Worst case, we should have at least held something as hostage for the pausing of the exercises. This one really puzzles me on multiple levels. How can a president tout spending billions on rebuilding the military as an accomplishment, then say a single exercise designed to ensure our ability to fight and win is too expensive? And what happened to coordinating with our allies? Just two weeks ago, Secretary Pompeo said there was “no daylight”between the US and South Korea with respect to the summit. Tell that to the South Korean Minister of Defense, who, upon hearing Trump’s statement, said , “At this current point, there is a need to discern the exact meaning and intent of President Trump’s comments.”

The joint statement signed at the end of the conference said nothing about formally ending the Korean War. This is surprising to me because that was a central premise to the Panmunjom declaration in April, 2018, and this joint statement goes out of its way to mention repatriation of war dead. Formal discussions for ending declared hostilities is a natural extension, and would seem to be an easy win for both sides, and something to work toward in a show of good faith. It’s puzzling that this was dropped completely from initial discussions, as both parties had mentioned it prior to the meeting.

The biggest challenge to denuclearization may possibly be on OUR side, as the DPRK has seen what a different administration can do to a previous nuclear deal (Iran). President Trump pulled out of the JCPOA ostensibly because it didn’t address ballistic missiles and Iran’s meddling in other country’s affairs, and only dealt with the nuclear issue. Kim will (rightly) think that if he makes a deal on nuclear weapons with the executive branch, what’s to stop the next administration from saying it was a horrible deal because it didn’t address his chemical/biological weapons, artillery fan in range of Seoul, human rights abuses, etc, etc. Thus, if he’s smart, he’ll demand a treaty instead of an agreement, and that may be a long sell in our polarized Congress – just as the Iran deal would have been – with some demanding the treaty should address chem/bio, conventional threats, and human rights abuses. That would be a non-starter to the DPRK. In the end, it may not be Kim that declares it must be a treaty, but the president’s own party. One of the reasons given for pulling out of the Iran deal was precisely that it wasn’t a treaty – with Senator Tom Cotton going so far as to mail a letter to the Mullahs of Iran giving them a lecture on how congress works. It’s going to be hard to say with a straight face that a deal codified solely by the executive branch is the way to go after all of the rhetoric in the past from the Iran deal, but a treaty may be a bridge too far.

The post Five Fast Facts from the Singapore Summit appeared first on Brad Taylor.

April 15, 2018

The Syrian Conundrum Part Four – Rinse and Repeat

After the latest strikes in Syria, President Donald Trump tweeted, “Mission Accomplished!” Besides the obvious subliminal baggage of using the same term that President George W. Bush used early on in a war in which we’re still embroiled fifteen years later, what, exactly does that mean? What “mission” was accomplished? And I mean beyond the partisan divide. Beyond the left shouting that President Trump was “wagging the dog” to detract from his lawyer’s office raid and FBI Director Comey’s upcoming blistering memoir, and the right shouting that the strike was a stroke of strategic genius that reset every element in the Middle East.

Speaking of wagging the dog, let’s just put that to bed right up front. Yes, President Trump has had a string of bad press, but he didn’t use chemical weapons in Syria. Assad did. And the very fact that both Britain and France were willing to strike unilaterally should completely lay to rest the idea that President Trump was executing solely for personal benefit. To do so stretches the bounds of credibility.

Even given the strike was done because of the heinous actions of the Assad regime, what, exactly, did it accomplish? The answer, unfortunately, is very little. The strike was designed for one thing, and one thing only: to deter Assad from using chemical weapons in the future. The administration has stated repeatedly that it has no interest in regime change, and in fact stated it was withdrawing all US troops in the very near future just one week before the strikes occurred. If there is one lever to deter Assad from doing anything, including using chemical weapons, it is to threaten his survival – and we’ve already given up that card.

Understand, I’m not saying we should conduct regime change, because that answer would entail a wholesale invasion of the country with ground forces, and follow on stability and support operations just like we did in Iraq. Those saying we can just kill Assad with missiles are making the same mistake Obama made in Libya – namely turning the country into a terrorist mecca – only this time, all of the armories that would be looted contain WMD, and we most certainly don’t want Sarin nerve gas to fall into Jihadists hands. Thus, if we want to conduct regime change, it will require securing those chemical sites and stabilizing the country. Very few in the United States would think that was in our best interests, but the fact remains that Assad’s existence is the only lever that will prevent him from using chemical weapons in the future.

In April of 2017, after a Sarin nerve gas attack, we struck an airfield precisely to deter him from further chemical weapon’s use. At that time, I wrote a blog saying that the strike would succeed, and that Assad would be insane to use chemical weapons again. I was wrong. By the administration’s own statement on the current strikes, less than a week after that attack, he used chlorine gas. We did nothing. Since then, he’s used chlorine gas multiple other times, with no response from the international community. Why are we so surprised he used chemical weapons again? In fact, I’m pretty sure it was he who was surprised at the response. After all, we’d let him get away with it on multiple other occasions. What he learned from our 2017 strike was not to use Sarin, but that using lesser chemical agents, like chlorine, was okay, because those garner no response. And even after this latest strike, all we’ve taught him is that he’s safe. Make no mistake; if a situation occurs – like the problem he had in Douma – where chemical weapons will prove decisive, he’ll use them again. The tradeoff is something he’s willing to make.

Douma was the last rebel holdout in the suburbs of Damascus. Assad, with Russian help, had bombed that place with conventional munitions until it was a shell. Hospitals, schools, homes, it didn’t matter what he did, the rebels remained defiant. Until he used chlorine. Shortly after that attack, they were loading up buses and evacuating. He achieved his objective, and all he got in return was a few missiles lobbed his way against targets that were specifically chosen not to affect his hold on power or involve any danger to his allies like Russia or Hezbollah (Iran). A tradeoff he’s more than willing to make in the future.

One of the fears from this strike is that it will escalate into World War Three because Russia will now retaliate in defense of Assad, but that’s absurd. Yes, there’s most definitely a risk if we’d harmed any Russian elements, but we made sure that the targets were clear of such things. Because of it, there is absolutely no reason for Russia to do anything – and they won’t, because they’ve won. Assad is in power, and anything they did against us would jeopardize his ability to remain so, because it would bring us deeper into the conflict. Why would they respond when the administration has publicly stated its desire to completely withdraw? Retaliating against us goes against their best interest, and if anything, Putin is a chess player. The most Russia will do is yell during UN meetings, but even that is a weak jab, given its use of nerve agent in the United Kingdom to kill a double agent. Currently, the world is not very tolerant of Russian statements against retaliation for chemical weapons use, and Putin knows it.

So what can we do if/when Assad uses chemical weapons again? Another airstrike? Rinse and repeat what we did before? We struck three chemical weapons related sites during the latest attack, but by the Pentagon’s own assessment, Assad still has the ability and the stockpiles to use chemical weapons again. Even if we hit them all, chlorine gas isn’t that hard to manufacture. It’s not like Sarin, and it’s a dual-use chemical. Basically, it’s concentrated, weaponized bleach. So what’s the point of striking more suspected chemical facilities? It would only make us look ineffectual and weak to supporters of the Syrian regime–which I personally believe we do to a certain extent inside Syria. But there is something we could hit. It’s something that would mean a great deal to the Assad regime, and would touch upon the regime change theme in a way that would resonate with him. We could strike his means of delivery – meaning absolutely destroy every airfield and air asset he owns.

Assad doesn’t really have an edge when fighting on the ground. Force on force, he’s not much better than the various rebel groups – especially now, after years of conflict honing the battle edges of his enemies. It’s the very reason he used chemicals in Douma. He couldn’t win a conventional fight in that suburb. His only edge is air power – the vaunted barrel bombs – and he uses them with impunity. It’s also the means by which he’s delivered the last few chemical strikes, including the two that caused our retaliation. If we threatened to destroy that, using the chemical weapons rubric as our rationale, it would also threaten his regime, because he cannot win without air power. I believe that would alter his calculus.

This strategy is not without risk, however. Russia has placed elements at every airbase in Syria, precisely as a hedge to get us to hesitate against striking them, so the escalation calculus would be high, but not as high as everyone thinks if Putin believed we were serious about the threat. He doesn’t want to go to war with the United States anymore than we want to go to war with him, and if he believed our resolve was iron clad, he’d pull his men before an imminent strike. Hell, we could call Putin on the phone and tell him we’re about to strike to mitigate the risk – just like we did before the April strike of 2017. It’s not like Assad can hide an airfield, no matter what the Russians told him. The most he could do would be to evacuate his men – which is fine, because that’s not the target.

The key, though, is to telegraph that threat. Our purpose is not to attack, but to deter future chemical weapons use. Thus, we’d have to be specific. The UN ambassador, Nikki Haley, stated that President Trump told her that the US was “locked and loaded” if they used another chemical weapon. This is meaningless. We should be specific on the threat. Telling Assad we are prepared for another round just signals that we’re going to repeat strikes one and two, which Assad would be more than willing to absorb. Deterrence is based on a credible threat against something the targeted country holds dear, along with the will to execute that action. Which means stating the threat up front and projecting the resolve to execute.

In the end, these limited strikes do nothing to justify the phrase “mission accomplished”, but they could, if we threatened something Assad valued in a future strike. The administration’s shown a willingness to use force, which is half the equation. The other half is to target something Assad values – and his air power is a direct line to his ability to maintain his regime. In the same way chlorine is a dual-use chemical – something that’s used for legitimate purposes as well as a weapon – so is his air power. We could threaten that because of his use of air platforms to deliver chemical weapons, and in so doing threaten his regime without overtly stating that is our goal.

Let him figure it out – I’m willing to bet he does.

The post The Syrian Conundrum Part Four – Rinse and Repeat appeared first on Brad Taylor.

February 16, 2018

Another tragic shooting, and the same tired arguments. Why is that?

After the Las Vegas Massacre, I wrote a blog for FoxNews.com. After the tragic events in Florida, I thought it was appropriate to post it again here, on my website. Not to start a debate, but to show where the debate now stands and why nothing gets done. There are sensible gun safety regulations I would support, but honestly, because of the partisan world we live in, I have no faith in the opposition to offer anything that would prevent the tragedy that occurred, instead using the tragedy to attack law-abiding gun owners. From October 7th, 2017:

Gun control is the hot topic of the day, and as usual it’s devolved into entrenched positions where many people supporting the Second Amendment will not give an inch, no matter the proposal. Why is that?

Do people who own firearms really believe that everyone should have the right to legally modify an AR platform so that it nearly duplicates the cyclic rate of a military assault weapon?

I had this conversation recently with a friend of mine, a former special operations soldier, who now makes a living providing firearms instruction to police SWAT units. As for me, I own two AR platforms, several pistols, shotguns and other rifles. I’m also a former special operations soldier, a member of the National Rifle Association, and support and defend the Second Amendment. We both agreed that bump stocks should be illegal.

Previously, bump stocks were simply toys that allowed recreational shooters to pretend they were firing an automatic weapon on the range. Because of the bump stock’s firing system, it isn’t inherently accurate, and the wasting of ammo using it relegated it to a gimmick. That was before the massacre in Las Vegas.

Bump stocks are no longer a gimmick. Accuracy became irrelevant when the target set was a crowd of 22,000 concert-goers in an open field in Las Vegas, where 58 people were shot dead and nearly 500 were hospitalized when a gunman opened fire last Sunday in the worst mass shooting in modern U.S. history.

Fully automatic weapons are currently prohibited without an enormous expenditure of time, effort and money. Any mechanical device that is designed to enhance the cyclic rate of fire of a semiautomatic weapon to duplicate that capability should be illegal – and should include devices separate from the bump stock, such as hand cranks.

I imagine the majority of gun owners would feel the same way, although I’m sure I’ll get hate mail from some.

After some vacillating from members of Congress about studies and research, the NRA finally issued a statement Thursday that called on the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives “to immediately review whether these devices (bump stocks) comply with federal laws.” The statement added: “The NRA believes that devices designed to allow semi-automatic rifles to function like fully-automatic rifles should be subject to additional regulations.”

Why did the NRA and staunch Second Amendment defenders in Congress not immediately call for making bump stocks illegal after the deadly rampage in Las Vegas Sunday? Why the equivocating when the issue is pretty clear-cut?

The answer is that gun owners see the fight in zero-sum terms, believing that the other side doesn’t care about preventing another Las Vegas, but instead wants to attack firearms ownership however it can. There is no faith in the intentions of gun control advocates, and for good reason.

The blood hadn’t even dried in the streets of Las Vegas before the de facto leader of the left, Hillary Clinton, tweeted about a suppressor bill currently in Congress. Immediately, the Twittersphere took up the charge, proclaiming that if the killer had used a “silencer,” the death toll would have been exponentially worse.

This is absolute hogwash, as everyone who has a modicum of knowledge about guns knows. To us, it’s a window into the true agenda. Hollywood would have you believe that a suppressor renders the bullet whisper quiet. That is simply untrue.

The shooter was four football fields away from his victims, and the sound everyone hears on the videos is not the explosion of the gunpowder, it’s the noise of the bullets breaking the sound barrier, something the suppressor does nothing to muffle.

In fact, the average suppressor simply lowers the gunfire to hearing-safe levels, but it’s certainly still loud (full disclosure: one of my AR rifles is suppressed). The fact is that suppressors would not have increased the death toll in Las Vegas, and Clinton knows it or should know it – even if her minions do not.

And yet Clinton used the tragedy of Las Vegas to further her agenda of attacking anything pertaining to firearms instead of working toward a solution to prevent a future mass casualty event. Gun owners see this, and instead of encouraging dialogue across the divide, it simply stiffens their will to resist.

Make no mistake, among ourselves gun owners are the first to decry the heinous use of a firearm. But when faced with the clearly partisan and cynical use of every event to further an overarching agenda, we close ranks reflexively – even over something as simple as the bump stock.

Gun owners are not evil. But we do fear the hidden machinations of the people espousing “common sense solutions” – especially when the proposal in question is anything but. If we as a nation truly want to work together to prevent tragedies like Las Vegas, the first requirement is trust in the good faith of the other side, and as Clinton just illustrated, that trust isn’t there.

The post Another tragic shooting, and the same tired arguments. Why is that? appeared first on Brad Taylor.

July 29, 2017

Transgenders in the Military? Please stop the Hyperbole – It’s Not About Equality.

President Trump’s tweet on transgender personnel serving in the military has generated enormous controversy, but – besides the incredibly idiotic way it was announced (I’m sure PACOM now has a staff duty officer whose sole function is to look at Trump’s twitter feed for “I’m going to war with North Korea”) – the actual issue is being buried in the weeds of emotion.

First off, even though I’ll be tarred and feathered with the following slurs, let me say upfront I’m not homophobic. I’m not transphobic. I don’t wish any ill will to the LGBT community at all, but I agree with a prohibition against transgender personnel enlisting in the military, and it’s solely based on the purpose for which the military is designed: To fight and win our nation’s wars, period.

Before I’m castigated as a bigot, my issue is a simple one: The transgender enlistee requires medical care after enlistment. Gender dysphoria is a medical condition. Plain and simple. It doesn’t make one any less of a human than someone diagnosed with high blood pressure or a curved spine, but it does require medical care. Beyond the hyperventilating about discrimination or hate, that fact – like the above-mentioned maladies – is a reason for disqualification.

In the past, the US military had one purpose: To defend our nation. The individual voluntarily succumbed to the greater national good. If the individual benefitted, it was secondary to the cause of the nation. Now, certain individuals have eclipsed the purpose for serving, and the military has assumed a secondary role of some cultural touchstone whereby serving is an individual right.

Why should someone be allowed to enlist, knowing that the enlistment will entail medical costs due to mental health management, hormone treatments, and other procedures up to and including gender reassignment surgery – not to mention the lost work productivity for all of the above? Why is that fair to the millions of others who wish to serve who also have a medical condition? Or even a non-medical condition, such as being a single parent or having a wrong tattoo? Why is it fair to allow a transgender to enlist – knowing the medical costs on the other side from the time of enlistment – when someone with high blood pressure cannot? That’s treatable. If he or she is otherwise fit to serve, why not enlist him or her, and begin treatment?

In an extreme example, why not let someone in with cancer? Why couldn’t John McCain, in an earlier life, have shown up to Annapolis with a brain tumor? After all, in hindsight, we know what he’s capable of. Why not treat it, and let him serve? Going further, as the military is looking for the best and the brightest, what if Lance Armstrong had enlisted right after winning the Tour de France? He takes his entrance physical and finds he has testicular cancer. Why should that be disqualifying? We know on the face that he’s capable of serving. Let him in, treat the cancer, and let him serve. That’s hyperbole, of course, but it makes my point. There is no overwhelming reason to incur the costs of medical care for any individual, and because of it, the military has a cut-line of medical restrictions for enlistment. In the words of Spock – the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. Unless, of course, you have a vocal lobby in congress. Then the military mission becomes secondary an individual’s “right” to serve.

I hear a lot of talking heads saying “we need whoever can best serve. We’re cutting our recruitment base when we discriminate”, but that misses a banal truth: The military is built on medical discrimination, and that discrimination is based on its mission. There is a reason you don’t see any soldiers taking the oath of enlistment from a wheel chair, and it’s not because the military hates handicapped persons. It’s because the military is not a social construct. It is a war machine, and it is designed to close with and kill the enemy, period. There are hundreds of different medical conditions that prevent one from serving, and saying we’re losing out on recruits by banning transgender personnel is a red herring. Why not say the same about flat feet, like they did in 1941?

At the start of World War Two, the United States had a population of 133 million people. At the end of World War Two the Army was about eight million strong. Today, the US population is over 300 million, and the Army has fewer than 500 thousand soldiers. The recruitment argument holds no weight. The bottom line is that emotion has taken sway over common sense. It is not the military’s job to create a position for the individual to self-actualize – especially if that self-actualization entails medical treatment at taxpayer expense. I feel for the transgender community, but no more than I do for the person with a hyperthyroid disorder or asthma. Neither can enter the military, but one has a political lobby that treats this as a civil rights issue. It is not.

Yes, there are transgender personnel who have served honorably while hiding their condition, just as there are thousands of soldiers who hide other medical conditions to serve, but that is not an argument to alter the enlistment standards. I know of a soldier who wanted to be a pilot, but found out he was color blind, which was a disqualifying condition for pilot training. He joined the Army instead of the Air Force, and then, after joining Special Forces, he learned that color blindness was also disqualifying for becoming a free-fall parachutist. He decided to hide it, ripping out any reference to colorblindness from his medical records and going to extraordinary lengths to pass the color vision tests over and over again. He succeeded for over a twenty-five year military career, but he would be the first to tell you that we shouldn’t drop color vision as a discriminator for HALO status. It’s there for a reason, as he discovered on a harrowing night jump.

The fact remains that gender dysphoria is a medical condition, and that diagnosis requires medical treatment the same as a host of other disqualifying medical ailments. A recent RAND study is routinely held up as showing that the medical costs incurred by transgender enlistments is negligible – a veritable drop in the bucket to the overall defense budget – and that may be true, but it’s also irrelevant. The same could be said of the majority of ailments currently proscribing one from serving. (Which also begs the question, if it’s so negligible, it’s proof that so few transgender are serving that the recruitment argument is meaningless. Why are we pole-vaulting over mouse turds for such a small minority?) Should we now simply drop all medical discriminators? Or is it just the LGBT community that gets the benefit? Why can’t someone with high cholesterol get in? Sure, they’re at risk for heart disease, but it’s treatable – and the cost would be negligible when compared to the overall defense budget. What about vision tests? A person disqualified from serving due to poor eyesight that could be fixed simply by a Lasik procedure? Why don’t we let all of them in, and give them the procedure – something that’s a hell of a lot cheaper than gender reassignment surgery? That, too, would be a drop in the bucket when compared to the overall defense budget, but do we really want the military to be in the business of fixing every problematic medical condition so that every single person who wishes to serve gets the ability to do so? Sooner or later, it’s no longer a drop in the bucket, and it’s a Pandora’s box that doesn’t need to be opened for the simple fact that it is unnecessary. A single day lost or a single dollar spent due to gender dysphoria is one too many, and it’s patently unfair to others who wish to serve but are denied that ability due to a medical condition outside of their control.

At the end of the day, we need to remember the mission of the military. The LGBT community has turned this into a crusade, but it doesn’t alter the facts. The military is not built to serve the individual, but the other way around. The individual serves the military – and by extension, the nation. It is a shame that an accident of genetics caused someone to be transgender, and thus disqualified, but no more so than my friend’s genetic abnormality with color vision. His desire to be a pilot in no way translates to our nation’s obligation to let him become one.

The transgender community is estimated at 0.6 percent of the US population. The rate of disqualifying high blood pressure in the typical age for enlistment, per the American Heart Association, is 9 percent. Where is the outrage over the nine percent with hypertension? A completely treatable condition? Why does the fraction of a percentage of the transgender community have a cudgel to pound, as if that population somehow holds greater sway than the millions of others with treatable medical conditions?

Take away the emotion, take away the tweets, take away the hyperbole on both sides of the aisle, and you’re still left with one immutable fact: A transgender individual has a medical condition that requires treatment, and that, in and of itself, is disqualifying. It has nothing to do with gender, bigotry, or intolerance, and everything to do with the mission of the US Armed Forces. The mission is what it is, and bending the security of the nation’s defense to placate a vocal minority is not enhancing our ability to prosecute it.

Postscript:

Before I get the question: If transgender personnel are currently serving in good standing based on a prior decision by the Secretary of Defense, then they remain, getting whatever medical treatment was promised by that decision. It is not their fault they came out based on a promise by the SECDEF, and a promise is a promise. This blog is solely focused on future enlistments for the reasons I described. For the uninitiated – In 2016, Secretary of Defense Carter stated that transgender personnel could now openly serve, but future enlistments would be on hold until a study could determine the impact. That study is currently underway, and this blog is solely input into the future enlistment question, not retroactively rescinding a decision – and thus punishing – those already serving.

The post Transgenders in the Military? Please stop the Hyperbole – It’s Not About Equality. appeared first on Brad Taylor, Author.

April 9, 2017

The Syrian Conundrum Part III: Crossing the red line…Again

To say the least, the Tomahawk strike on Syria has caused a great amount of chatter throughout the world, but most of it is misplaced and some is outright outlandish. I thought I’d weigh in, not in a partisan way, with an agenda, but simply to clear the air a bit. So here, in no order of precedence, are the primary questions being asked:

Who did the chemical strike in Syria?

The minute I heard that chemical weapons had been used in Idlib, the first thing I thought was, “That makes no sense whatsoever. It has to be the rebels.” Assad, for all his faults as a dictator and a murderous thug, is nothing if not a survivor. Two days before the attack, President Trump acknowledged this. Both his secretary of state and his ambassador to the UN said that his removal was no longer a goal of US policy. For Assad, this is a win-win. Through Russian and Iranian help, he is slowly but surely winning the civil war in Syria, and without outside interference, the endstate is preordained. What, on the surface, would cause outside interference? A horrific act, such as the use of chemical weapons.

So why on earth would Assad do such a thing? It doesn’t make sense. For one, chemical weapons are designed for a specific reason. Yes, they kill, but they do more than that. They deny terrain, block approaches, generally make areas uninhabitable, or instill terror that forces the other side to capitulate. Unlike a bomb that just explodes, they present a problem that has to be resolved long after the strike. It’s why they were invented. In this case, the weapon used did none of that. It wasn’t even in an area with a concentration of rebels. A conventional bomb could just as easily have been used. But it wasn’t. So why on God’s green earth would Assad choose to use it, knowing the outcry that would be engendered, and knowing President Trump’s chosen policy position?

One possibility is he didn’t do the strike, but someone inside his orbit did. Someone who was now antithetical to his desires, and knew the strike would cause massive repercussions that might cause his downfall. I thought about this for a bit, but found it far fetched. Assad officially turned over all of his WMD after the 2013 Obama fake “red line”, which means any he kept behind would have been under serious lock and key. A dissident regime member would need a significant number of like-minded men to load, arm, and use a WMD from an aircraft. The weapons would be kept separate from the usual ordinance, with significant restrictions on their withdrawal, and even more on having them loaded on an aircraft. So, you’d have to have an enormous conspiracy of high level members of the regime who a) knew where the weapons were secretly stored, b) had the ability to get them out to use secretly, and c) hide such a thing from an entire strike package of pilots and planners. It’s much more than a single aircraft, and it just doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

Another possibility is it was a rebel strike (or a strike on a rebel chemical facility, which is what Russia is claiming). Initially, this held water with me. It’s the only thing that makes sense, given the state of play and the fact that the weapons’ use held no extra value to the regime. A conventional bomb would work just as well, and the downsides to chemical far outweigh any upside. Two things overcame my doubt: One, every intelligence service on the earth (outside of Russia and Wikileaks) states it was the regime. Admittedly, I’ve heard this over an over for the last few days, but still thought, “That doesn’t make sense. Am I falling for a narrative to uphold a strike?” In fact, the alt-right conspiracy theorists are saying just this thing – that it was a “false flag” attack perpetrated by the “deep state” (so American “cuckservatives” did the attack? I can’t keep up…) to engender a response. For them, the term “false flag” is a catch all that’s been used for everything from the Murrow Federal building to Sandy Hook, with 9/11 in between, so I had a little cognitive dissonance when I found myself agreeing with them. But as the saying goes, just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean someone isn’t out to get you. So what’s the proof that it was the regime?

This strike held something different: It was Sarin nerve gas, and that is not easy to manufacture, and even harder to stabilize and weaponize. The only other time Sarin was used was also by the regime, in 2013. Since then there have been several more chemical attacks in both Syria and Iraq, but they were of a lesser variety, using chlorine or mustard gas, both of which are far easier to manufacture than Sarin. Sarin is a killer of the first order, and is something that requires a state capability to produce and weaponize. You can’t make it in a bathroom, unlike mustard gas.

The fact that Sarin was used implicitly implicates the regime. But maybe it wasn’t Sarin? Maybe anti-Assad forces are just calling it that because they know the repercussions. I’d believe that but for two reasons: 1) As I said above, there have been multiple chemical attacks in this war since the 2013 attack, and none of them have been called Sarin. They’ve all been called chlorine or mustard, so it doesn’t make sense that everyone in Syria would suddenly start calling THIS attack Sarin. 2) Multiple autopsies, both from inside Syria and outside, have stated that the gas used was Sarin. This leads to the conclusion that it was, in fact, Sarin, which leads to the ultimate conclusion that it was the regime. No two-bit rebel group – not even ISIS – would have the capability to manufacture the weapon in question. Which means it was from the regime.

At the end of the day, as idiotic as it appears, it has to be the regime. It’s Occum’s razor here. So why do it? My thoughts: As I said in a blog from 2013, after watching what happened to Qaddafi when he turned over his WMD, Assad would be stupid to do the same, and I didn’t think he would back then. From that blog:

If anything, Assad has looked at the past and realized one of the few things keeping him in power are precisely his chemical weapons. One of the primary – and smart – reasons we haven’t conducted “regime change” with him like we did with Qaddafi is because we’re afraid of those weapons ending up with a bunch of fanatical jihadists. If he relinquishes his weapons, he loses that edge, and as I said before, his survival is the only thing he holds dear. In fact, I’m sure he’s looking at recent past history. Under President Bush, we convinced Qaddafi to give up all of his WMD capability, verified by international inspectors. Fast forward ten years, and President Obama is launching airstrikes to remove him, regardless of the jihadist rebels and regional chaos that would follow his fall. Assad knows full well that if Qaddafi had kept his WMD, there would never have been any NATO airstrikes because the west would have feared the consequences. With the WMD out of play, the west could pretend to be humanitarian by dismantling Qaddafi’s regime, and then allow the country to fall into chaos without worrying about the aftermath. After all, it’s way, way over there and not something that can affect us. Throw WMD in the mix though, and we’d spend a little more time debating the outcome before slinging missiles. No, if Assad’s learned anything, it’s keeping his weapons (and using them), only garners a potential pinprick, but giving them up guarantees his eventual fall.

Turns out, I was right, but having the weapons hidden does him no good. He needs to let folks know he has them, as that is the one thing that will give us pause on his overthrow. He needed a small strike to show that he did, in fact, have such weapons even after he said he’d given them up, and with the early assurances of the new administration saying he was not a priority, he decided to let the secret slip. He was putting the world on notice that he does have WMD, and if we overthrow him they will fall into the hands of the chaos left behind. The only counter-balance to Russian and Iranian attempts to prop up the Assad regime was/is the United States, and Assad had a moment in time when the administration stated that he was no longer a target. Given that pause, he wanted the world to know he HADN’T given up his WMD, and his downfall would cause those to be unleashed in terrorist hands. For him, it was a bulwark to protect his regime, and he read the backlash for what it would be – a limited strike – but also knew the back-room chatter in places that matter for his survival would completely change. Now, removing him would involve significant repercussions beyond just quibbling over who would be in charge after his fall. It would involve containing a clear and present danger to us, and in this gambit, Assad more than likely succeeded. Violent overthrow of his regime is not something we’ll likely pursue now, so as loony as it seems on the surface, there is some strategic logic in Assad’s strike.

Or, maybe he’s just batshit crazy. Either way, the above will play out.

What did our retaliatory strike gain?

On the surface, the strike did little to the Assad regime, so little, in fact, that aircraft were taking off from the same airfield we hit less than 24 hours later, but this is shortsighted. The strike did two things – and both of them are game changers. One, it showed that the US is willing and able to use military force for a transgression involving chemical weapons. I said this in 2013, namely that you can’t create a redline and not enforce it. Chemical weapons are unlike others. Some say that it’s ridiculous to go haywire over chemical and then sit back while conventional munitions slaughter – and there is some credence to that – but allowing chemical munitions to be used without repercussions is allowing an expansion of sanctioned violence that is antithetical to the world order. To the layman, it may make little sense that we care whether someone is killed with a bullet or suffocates to death by neurotoxin, but there is a difference, just as there is between dying in battle and getting burned alive on video by ISIS. The fact remains that there is a world order, and that order is predicated on precedence. Allowing these attacks to continue sets precedence for any other two-bit dictator out there. This strike put a much-needed marker down.

Two, on a bigger geopolitical scale, it showed that the United States is willing to use force, period. That, on the surface, should be a given, but with Obama’s missed redline in 2013, it’s most certainly not. Telling someone in a bar that if they bump you one more time, you’ll hit them, is a hell of a lot different than actually getting bumped and making a choice. At that point, you have two responses: Hit them, or not. When you don’t, you tell everyone else in the bar that your bluff was just that – a bluff. Whack them in the head and everyone else sees the blow – and that everyone else is North Korea, Iran, Russia, and every other state that wants to bump us. Trump just put them all on notice that the bump WILL engender a response, and the response of the US arsenal is a pretty heavy thing to go against. Make no mistake, the strike was limited, but the calculations now going on in every seat of government – both friendly and enemy – is wildly different from three days ago. All of Trump’s isolationist rhetoric on the campaign trail just went flying out the window, and the world took notice.

What does this mean for the outcome of the civil war in Syria?

Very little. I hear the pundits on TV breathlessly claiming that the strike has altered the calculus of Russia/Iran/Assad, but that’s not the case. The goal, pure and simple, was to prevent Assad from using chemical weapons in the future, and in that, it will succeed. Assad would be a lunatic to use them again – but if I’m correct, he got what he wanted out of the strike. The world now knows that he DIDN’T give up his WMD, and if he falls, so do the chemical weapons stockpiles. The strike will in no way bring him to any negotiation table – especially if he still has the support of Iran and Russia – and will not lead to more involvement by the United States. It’s not, as some have stated, mission creep whereby we’re now obligated to put boots on the ground to get rid of him. Three days later, Trump’s primary policy remains – defeat ISIS – and I don’t see that changing with the dynamics in play involving two other state systems. At most, we did what we set out to do – namely, we won’t tolerate the use of chemical munitions – but the slaughter will continue with little substantive changes to our strategy. This strike was a one-off, unless Assad does something heinous – and he’s not that stupid.

Was the strike legal?

Yes, it was. Quit your damn bitching, Tim Kaine. Where were you when we went into Somalia, Bosnia, Kosovo, Sudan, or Libya? Oh wait, those were under democratic administrations. That must be why they were legal.

What could happen that we didn’t anticipate? What’s the second or third order effect?