John Elder Robison's Blog

March 4, 2025

I can never forget I'm different, no matter how I try . . .

This morning I was at the gym as part of my twice-weekly effort to halt my inevitable decline. As I lay on the floor, twisting myself in knots, two people were talking about their respective travels. One was just back from Virginia and Arizona after touring two schools with her son. The other had been to Louisiana and Pennsylvania for the same thing, and they compared their journeys and the t-shirts and other swag they returned home with.

One asked the other how her kid felt going across the country for college. The other talked about how she felt with all the traveling back and forth. On my back, on the floor, I considered that I had no experience whatever like theirs.

I’ve been to all those states and more, visiting their universities to talk about neurodiversity and autism. But I never had the student experience. I never left home for a dorm, never experienced class as a student, and when I got older and had a kid, he never did those things either.

It’s not that we are uneducated; it’s just that neither of us needed a college to get there. The idea of spending four, six, or eight years studying something I want to do is somewhat unfathomable. I have never been described as incompetent or unskilled at anything I’ve done, even as I taught myself what I needed to know on the fly.

I realized that is one more example of how my different brain sets me apart from others, that I never had those college experiences either as a student or as a parent. Perhaps it was my social disability – which was significant early in my life – that kept me out of school. There was also the small matter of flunking out of high school – which I now attribute to the school’s focus on “doing things the way they teach” and requiring me to “show my work.” Correct answers alone were never enough.

Whatever it was – probably a combination of things – I abandoned the school track for training myself on the fly. Time has proven that to have been a winning strategy for me. But it also isolates me, at times like this morning. I had nothing to add to that conversation; all I could do is listen and ponder how different that was from my life.

No matter how successful I am; no matter how many people like me or love me, I am reminded at moments like those that I am always different, and it makes me feel a bit sad.

I didn’t choose to be how I am; it’s the only life I know.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder RobisonNovember 12, 2023

The Future of Trades

Prior to the rise of the Internet, people found things through advertising, or referrals from trusted individuals. The more important the thing, the more likely someone was to seek a trusted referral. A prospective homebuyer might follow advice from a friend or acquaintance who recently bought a home. That might lead to the selection of a realtor, who in turn would suggest a home inspector. When they identified needed work, contractors recommended by the realtor or inspector would perform it.

Recommendations for a dentist, a restaurant, or a car mechanic all came through similar channels. In most instances, no compensation was offered or expected for the referral. People felt comfortable following the advice of others they’d come to trust.

During the 20th century the rise of cities and increased mobility led to a breakdown of personal connections. Someone in a small town might know people to advise them on most anything they could want or need in town. The same person, transplanted to Manhattan or Chicago, would not have such a network. Where would they turn?

The Internet evolved to provide an answer. Today, anything we want is offered online. But how do you know who to trust? The internet has existed long enough to replace “community trust” with “good online reviews” for a whole generation. That shift has created great opportunity for a small group of web-based entrepreneurs and their private equity backers, at the expense of much of the general population.

The replacement of trusted personal recommendations with online reviews has led to the proliferation of junk at every level of commerce. Cars are a good example. In any community, sellers exist to provide cars at all levels. New car dealers provide the best cars to affluent people, and they also sell used cars to slightly less affluent folks. Other used car dealers provided progressively more worn cars, at progressively lower prices, to less prosperous people with lower expectations.

While the customers of a Cadillac dealership and a discount car lot might be totally different, both dealers were aware of their place in a community, on whose goodwill their livelihood depended. Today, most car dealers offer their cars online and a significant number of sales are made to people out of their local areas. Dealers don’t feel as accountable to distant online buyers, many of whom they never meet. Warranty laws make buyers responsible for returning a defective car to the dealer for repair, and when the dealer is far away, that may be impractical so in effect cars are sold without as is, and with no ties to the community.

Knowing this, dealers are able to sell cars they would not have been comfortable selling to a local customer, and the overall quality of goods they sell is diminished by the internet. In person car buyers always ran the engines and looked at flaws. Online buyers participate in a fantasy market where every car is nearly perfect on the website, no matter how it might appear in real life.

The same is true for a million other products – it is impossible to tell the gems from the junk online and many items are less than what people hope for. This problem extends to the purchasing of services which are a growth area for internet marketers.

When home inspectors depended on the goodwill of realtors to refer clients to them, they tended to be responsive to the folks who sent them work. They had to do a good job, in order to keep getting referrals. In a small community, the feedback loop between the home buyer, the realtor, and the inspector was a tight one, and it fostered a strong level of trust. It also created a trustworthy world for many people. A homebuyer coming into the market could have a reasonable assurance that a realtor they engaged would look out for them, and give them good recommendations, because they lived in the community they served, and bad news can travel fast.

By that means, in the pre-Internet world, a person who was new to an area could still seek and find good referrals for things they needed to establish a good life. Today, that model has largely been supplanted by a faceless Internet. One overlooked result of that change is the effect on the upward mobility of aspirant small business people who provide the services.

In the community based model, business was driven by referrals, and the referrers and referrers were part of a mutually supportive network. Each member needs the others, and while there is some competition, there is also a recognition that their success is mutual. In the local model, an individual home inspector or handyman works hard, does a good job, and gets more and more referrals. At some point they respond by hiring an assistant, then another. At that point they have made the move from individual tradesperson to contractors.

Some of those new contractors may keep their same positions in the network, or they may seek larger jobs that require more resources, which they now control. The larger jobs tend to have fewer competitors and higher profits, which facilitates their scaling up even farther. Contractors can move from successful to wealthy.

That model still exists in many places in America, but it is facing competition from Internet-based alternatives who are increasingly the choice of young adults who grew up in an online world, with little to no reliance on trusted local connections.

Some internet service providers are also local. Community businesses market themselves online, often with website as simple as “lawn care in Anytown, USA.” Those people don’t always see the Internet as competition. But in today’s “pay to play” internet, well capitalized online competitors are at the top of search rankings, skimming the cream of all manner of local service opportunities.

The best known online service model is typified by companies like Uber, from whom contract workers receives a stream of jobs from the website, encouraged by promises of “more work, more pay.” But there is no upward mobility; the jobs are dead ends and the majority of the profit in the transactions goes to Uber’s managers and financiers.

There is no place for a local delivery service when Door Dash comes to town. The well-capitalized online firm lures drivers from the local service with the promise of better pay, and when the local service disappears, they charge the local businesses higher and higher delivery rates while cutting back on what they give their drivers. The result is a transfer of wealth at every level. Local delivery businesses fail. The drivers are paid the same or less. The restaurants and others whose goods are delivered are squeezed more, and the public bears the burden.

In trades like home inspection or plumbing, national operators evolved, many operating through local franchisees. In that model, the national company has the scale to manage an effective online presence, making them formidable competitors, especially for an individual aspiring to enter the trade. While a franchisee may do well under this system, there is little opportunity for the workers to become owners. In a traditional workplace, most workers have a expectation of higher wages with seniority, but that does not apply in most online models, where the value of a work assignment is fixed by the website, and everyone doing the job is paid the same.

In a traditional trade business the higher paid workers are put on more challenging jobs. With the Internet model, where there is no local evaluation and pricing, all the jobs are equal. Control is shifted to the machine, along with most profits of the endeavor.

The people who establish these online ventures call themselves disruptors and allege they are providing better service at lower prices. While few would disagree with their disruptive nature, their low price promise seems to dissipate, and few if any of the workers in these enterprises makes a substantial living.

The big winners are the creators of the online businesses and the private equity that finances them. The losers are the workers, who are pushed into more marginal situations with virtually no upward mobility.

Aspiring tradespeople can still participate in local referral networks, whatever line of work the choose. But most of those networks are seeing competition from online businesses that have no connection to the area, or a tenuous connection through a franchisee. The result is diminished opportunity for people who see the trades as a path to security and prosperity, and creation of vast wealth for the small number of people who create online replacements for local trade networks.

While the idea of “tech billionaires” is a well-worn trope, the idea that they are created at the expense of working people in the trades is relatively unrecognized. Local business has been the source of most wealth creation in America, and that system is now threatened by highly capitalized internet-based startups in the same way that Walmart and other big-box retailers decimated America’s town storefronts.

Every year, millions of people come of age, aspiring to success and security, with skills positioning them for work in trades or services. What should they do? That is the subject of my next essay.

(C) 2023 John Elder Robison

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder RobisonOctober 26, 2022

Getting Older With Autism - presentation to Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee Oct 26, 2022

I have been involved with autism advocacy for 25 years. Throughout that time, particularly during my 15 years of government service, I mostly advocated for autistic people younger than I. But at age 65, I am here to ask: What about the older autistic population? We have unanswered questions, and we also need support. I’d like to share some of the things I’ve experienced.

All autistic people have some degree of blindness to the unspoken messages of others. It’s part of the diagnostic criteria. What about blindness to ourselves? That is less studied but equally real. I don’t have a good sense of when I am hurt. I don’t know I’m too cold till I see the frostbite. I don’t know when to stop or when to back down. I don’t know how to read my own body.

When I was 50, that didn’t seem to matter much. If I miss medications now, I may die. If I overstress myself now, I may suffer injuries I can’t recover from. Every year the stakes for “failing to read my body” grow higher. Isolation is a recognized problem for autistic people and it’s worse in old age. How many people like me die alone because they are out of touch with their bodies and their needs, and no one is there looking out for them? No one knows.

Growing older, I feel I have gotten more autistic in some ways. The same is true for many autistic friends. We are more inclined to be alone; we are more isolated. Tics and mannerisms long lost, have resurfaced. I seem less mindful of the need to look at other people; my social skills have slipped.

That is contrary to my observations from a decade ago, and the findings of some studies, which say people with good cognitive ability tend to see their disabilities diminish with age. Ten years ago, I observed how much more successful I was in social situations than, say, at age 20. I saw how much benefit I’d gained from learning what my autistic strengths are, and how to use them to the best advantage – something that comes with life experience.

Those things are still true today, but they are less meaningful. I’m not as inclined to be social. I am more at home alone. My autistic technical abilities brought me success in many domains – engineering, music, photography, and writing . . . but I doubt I could replicate those successes with my current cognitive abilities. I’m not as flexible. Not as patient. Not as full of new ideas.

All those same feelings might well be expressed by any aging person. We hear of senior moments, slowing down. Are autistic people different in that regard? I don’t think anyone knows.

An old friend with autism had part of the answer. He said, “when I hit 55, it’s like my ADHD fueled energy just ran out.” That is very much how it feels for me. Ten years ago I served on this committee. I served on INSAR’s board. I held two teaching appointments and did 25 speaking engagements every year. All while running my automobile complex here in Massachusetts.

Looking back, it was surely ADHD-fueled energy that kept me going, and it isn’t there now. In terms of accomplishment, or my ability to accomplish things, that is a great loss. I cannot do what I used to take for granted. If I look at the diverse range of things I did in 2017 – five years ago – and the range of things I can do today, it is much more limited. That is not by choice. I cannot do it all anymore. My ability to juggle disparate cognitive-intensive tasks and get them all done was considerably better than average. That is no longer true.

Ten years ago, I was confident and full of energy. Now I am anxious, worried, and tired. There is no question that my anxiety has increased these past few years. Is that autism and aging? Or a side effect of covid? I don’t know, but before covid, I knew older autistics who became more anxious. At INSAR conferences, I saw older autistic friends become paralyzed by anxiety. That is a serious and overlooked problem in autistic people with otherwise good cognitive function, and I feel it worsens with age.

I have just enumerated some ways in which it feels like I’ve diminished with age. Luckily, I am surrounded by people who care about me and look out for me. Without that, in isolation, I can well imagine that I would come to the rational decision that suicide is my best option, as there would be nothing but pain to look forward to. As someone who has lived with depression and anxiety all my life, and who has been in that place more than once, I urge you to take that seriously. If I – seemingly well connected to society, articulate, and capable – can get to that place, how many of my fellow autistics who do not have my advantages, choose that way out?

The problem to solve is a societal one, not an individual issue. In earlier IACC meetings, we discussed the emerging realization that intellectually disabled and non-speaking autistic people might have as much or more suicidal ideation as non-intellectually disabled autistics. Suicide is a lifelong risk for us, no matter where we fall on the spectrum.

A recent Labor Dept study found 7% of Americans were self-employed. A Dartmouth study of desire found 70% wanted to be. I’ve been self-employed most of my life because I had no choice. Being autistic, I did not have the social skills to navigate work life in large organizations. That’s a side of life the stats don’t capture. There is a way we can see it, though. The prevalence of autism and neurodevelopmental disorders among the homeless and incarcerated is well above the prevalence in the general population. Brugha and later studies show older autistics, as a group, end up worse off than the general population. Given the contributions we make to the world, that’s wrong.

At 55, I felt like I could keep working forever. At 65, I feel I have no choice but to work forever. Those are very different perspectives. I – and most older autistics – have absolutely no government, academic, or corporate retirement plan. In saying that, I am not counting social security and disability. I am talking about retirement funding that provides a decent standard of living in retirement.

The only retirement I have is what I make, by investing and building assets. It’s easy for any older person to say “that’s just the same as me,” but it’s not. Those of you with government, tenured academic, or corporate jobs get your retirement security by being part of a social system where you are employed. As long as you remain in the social system for the duration, it takes care of you. I know of no statistics on this, but I suspect the number of autistic adults who successfully run that social skills gauntlet is small.

Reflecting on that, I realized the issue is not the money. Now, don’t get me wrong – money for retirement security is very important. But I think the social network afforded us by employment is actually even more important. That is something I could not see when I was young but I see it very clearly now. Work is the place where so many people make friends, find life partners, discover new interests, and join a social web that nurtures and protects them in times of stress. In that respect, the workplace is far more than just a job.

Years ago, when I tried to fit into a large company without success, I sneered at the people standing around the photocopier, gossiping. Why weren’t they working? They were just wasting time. Now, I realize that gossip I thought was a waste of time actually nurtured those people and represented valuable social support for many. Reflecting on my attitudes at the time, it’s fair to ask: Did they exclude me? Or did I exclude myself?

To help autistic people fit into workplaces and become more socially connected, I would start with this suggestion, which I suspect every autistic person listening will agree with: Fix the ugliness in our schools. That’s a tall order, but that ugliness not only leaves millions like me with psychic injuries – and the resultant disabilities - that last a lifetime; it is the breeding ground for today’s bumper crop of school shooters and others who pose a far greater threat to society than people like me. Our mistreatment in school throws up barriers to success at work.

That stigma of childhood rejection follows us into adulthood, where it joins with our autistic social disabilities to cause endless missteps in our efforts for social engagement. Many autistics respond by withdrawing. Others turn to drink. Some succeed in connecting, either with one person (and that may be enough) or with many. Many of us succeed at some level, but we live with more sadness, anxiety, and isolation than anyone would want.

There is a whole generation of 40+ autistic people who grew up with no diagnosis. Many of us are just going along, aware that we are different from others, and often feeling we are “less.” With no understanding of our neurological differences, how could we see things differently?

Having talked with many such undiagnosed people, I believe the last thing they want is for someone to say, “Hey! You act autistic! You must have undiagnosed autism.” When presented with a potential paradigm shift like that, they reject it because of autism’s stigma. That was certainly my first reaction. But in my case, the therapist handed me Tony Attwood’s original book (Asperger’s Syndrome – a guide for parents and professionals), and he said, “No, really, it’s not what you think. Read about it”. He had highlighted passages that did indeed match me.

But the autism stigma was still a hard thing to overcome. At first, I saw a disease with no cure. I thought it was why I’d failed, and I’ll never get better. That’s not how discovery has to be for us. This is where neurodiversity comes in.

If we are presented with the neurodiversity paradigm instead of a medical diagnosis there’s a chance for a better outcome to those conversations. Hearing that we have a different kind of brain is fundamentally different from hearing we are “disordered.” We are stronger in some ways and weaker in others. We start by talking about balance, not a list of deficits. We start with diversity, not disorder.

The place I really see this happen is in workplaces with many neurodivergent people. I can give you one example. Some of you may know I am the neurodiversity advisor at the Lawrence Livermore National Lab. The lab is one of the world’s premier scientific institutions. Engineers and scientists at the Lab work on some of the most difficult scientific and technical challenges known to mankind. Success often requires extraordinary cognitive gifts. Often, those gifts are accompanied by diminished abilities in other domains. So many brilliant scientists and engineers have terrible trouble with human relationships. As an autistic person, I see neurodiversity at the root of that. Not autism.

If I were to say, “you act autistic” to an accomplished scientist, he would very likely reject the notion, because autism is a medical term for disability. Any conversation about autism starts with deficits. Deficits imply failure, and most people working at a place like Livermore would not be characterized as failures, no matter how they see themselves inside.

If, on the other hand, I explain how the neurotype that makes them so successful in the technical arena might hamper them in social settings . . . we have the basis of a conversation that leads to understanding. At the Lab, enlightenment has been as transformational for some of them as it was for me, years before.

So who might initiate these conversations? I think neurodiversity at work programs are going to move in that direction. One thing Livermore is doing in their neurodiversity work is directing the focus onto neurodivergent people who are already employed there. That’s where companies will get real benefits. Make a few thousand existing workers happier and more productive, and you win big; more so than anything you’ll get from a dozen token “ND at Work interns.”

Companies that believe in neurodiversity should see that the neurodivergent population they need to reach is not out on the street waiting to be recruited. It’s on the job right now.

Outside the workplace, once you are dealing with people who have aged out of the public school’s special ed supports, I suggest medical and counseling professionals begin to replace their autism language with neurodiversity language. Less stigma. More connection. We will need a lot of training to get medical and counseling professionals into this new space.

Here’s a final thought on neurodiversity in this space. You know me as an autistic person. But my multitasking was always in the ADHD arena. My errors in reading are dyslexia, just like my son. My tremors are hints of epilepsy and possibly Tourette’s. Saying I have a number of “comorbid conditions” verges on insulting, and it has no meaning to me. Saying I am neurodivergent . . . that feels like the right thing to say. That’s me. Others feel different. We should respect all our personal choices in that regard.

Before I ask for questions or comments, I’d like to offer these thoughts:

I served two terms on this committee, and I am proud of most of what I said and did. There is one thing I regret. I regret the times I criticized or mocked people who attacked me or said things I thought were ridiculous. To those of you hurt by my words, I apologize.

Serving on the IACC comes with a duty to advocate for ALL autistic people, no matter who they are or how they feel about autism, themselves, or this committee. Our job, in representing the autism community before the Federal government, is to do our best for all autistics, without favoritism. Today, you are here to guide tomorrow's scientific research as you are guided by today’s knowledge. Every person who comes before the committee went to some trouble to do so, and they deserve attention and respect. In the last years of my service on the IACC, I came to believe those words apply most of all to the people who oppose us or hold views we think are wrong or even dangerous. We are their representatives too.

It's up to you on today’s IACC to carry this advocacy forward, and I urge you to do so with kindness, respect, and wisdom.

John Elder Robison

October 26, 2022

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder RobisonJune 25, 2022

Scenes from the Big E 2021 Fair

If you like photographing people and action, it's hard to think of a better venue than the Big E - the Eastern States Exposition Fair, which happens in West Springfield, MA over 17 days, encompassing the last two weekends of September and the first weekend of October.

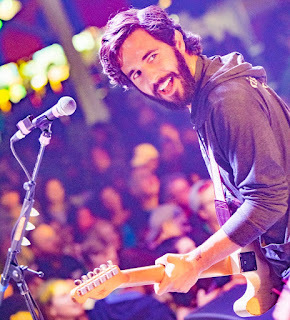

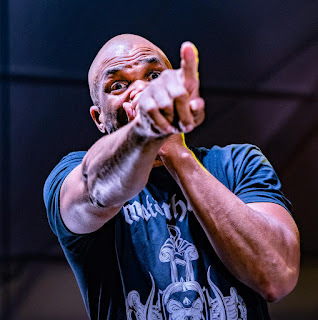

I have photographed the Fair for 25 years, and in that time I've see the transition from black and white to color, from film to digital, and then from one generation of digital system to another. 2021 marked the first year I shot the fair with mirrorless digital cameras, with most of these images shot with a Nikon Z7II. Others were shot with the legacy system, the still-capable D5.

Join me on the grounds again this September 16 weekend.

Who do you recognize?

What's your favorite?

All images copyright 2021 John Elder Robison - all rights reserved

March 21, 2022

Thoughts on Writing

It has been 45 years since I first got the idea of writing things people would notice. The first things I wrote were descriptions of electronic circuits I had designed – how they worked and what they would do. I did not have the literary skills of an author, but I had technical competence and a decent command of language. Most of all, I had a gift for explaining things in ways others could understand.

I did not realize it at the time, but those first missives were instrumental to success in my career in electronics. No one paid me for my writing, but it was my written words that brought me the work that sustained me. Even when my work spoke for itself I still had to write notes and proposals to get more.

In the mid 1980s I had moved into “executive” jobs where I was a manager, not a technical person, and it seemed like much of what I did was write and attend meetings, where things I had written about were discussed. In hindsight, I see the ability to write clearly was very important. Writing kept me employed, even though my job title was engineering manager, not writer.

When I quit electronics to fix cars, I set aside the Parker pen and the IBM Selectric typewriter. Now, I would be another kind of tradesman, picking up Snap-On wrenches instead. But the need to write was still there. I had to promote my fledgling business fixing cars. I had to establish my expertise. To do that, I began writing articles and submitting them to enthusiast magazines. I knew I could never buy a full page ad in a Land Rover magazine, but I was able to publish a full page article at no cost at all. The same was true for Rolls-Royce, Jaguar, Mercedes and other car magazines. I sent stories to all of them and most were accepted.

My business prospered and I saw links between my writings and people who brought work to the shop. “I read your article about . . . “ was the start of countless interactions.

Later on, when I looked on Internet writing forums, I saw how critical people were of that practice. Magazines who published the work of people like me without compensation were said to be taking advantage of us. I stopped giving people my articles for free. I began publishing them on my own websites, and licensing words and photos to groups who were willing to pay.

At some point in that journey I learned I am autistic and decided to write about that, in order to help young people like me see they could grow up to have good lives. That was the first “altruistic” writing I did. Seventeen years ago, my father died, and I wrote a story about that. My brother put it on his website, from which it was picked up by NPR and hundreds of thousands of people saw it. I was shocked. At the same time, my younger brother had written a book about our childhood that had become a bestseller, and I found some of his readers suggesting I write my story.

I did that, and when Look Me in the Eye came out, it and the writing that followed put me in front of millions. That book was the right story at the right time, and the success of the first book led me to write a second, a third, and a fourth. I wrote a dozen chapters for academic books and hundreds of articles. So many people read them that I became known not as an engineer, or a fixer of cars, but as an author. Despite that, I have always felt like a tradesman who uses words in furtherance of the trade.

While I was writing on autism and neurodiversity I continued working on cars. Or rather, I continued running a business that worked on cars. While the car company still does a lot of service, I found a more creative outlet in the restoration side of the business which has grown from nothing to most of what I do in the past decade. Writing is absolutely essential to that.

In the automotive sphere there are many large companies. An individual like me can never compete with them for ad space. The only way to build a reputation as a restorer was how I started in the 1980s – by writing stories about fixing cars and offering them to magazines. Sure, I read how magazines took advantage of “poor writers” like me, when they printed my stories. And I understand, the market may seem limited. If you were a publisher, how much would you pay for a 2,500 word article on rebuilding convertible tops on Bentley Azures? With fewer than 1,000 such cars in North America that is a pretty niche market, compared to writing about growing up with autism – something that affects one in thirty American families.

Let me share a secret. The “free” articles I have written about those arcane topics have brought a ton of work into our shop. They established our company as top experts and were instrumental to the success we enjoy today. Don’t think for a second I was taken advantage of by letting those magazines print my stories.

If I look at the return, per word, for the specialized car articles versus my bestselling books, the return per word on car articles is much greater than anything else I have written. Now, plenty of people would argue that the social value of my writing on autism and neurodiversity has brought far more to the world. I agree, and I’m proud of that, but it does not change the fact there would never have been a Look Me in the Eye if I had not first built a business that gave me the freedom to take the time to write on autism.

If you are someone who dreams of making money from writing, there is an important lesson here. It is incredibly hard to write a book, get an agent to read it, and get a publisher to buy and publish it. Once it comes out the odds of having a bestseller are tiny. Real financial success is so rare.

Writing those “free” stories – as I have done for 45 years – and using them to advance in business, build a reputation, or gain work for yourself or your company – that is surprisingly easy to do. If you do it right, you don’t need a bestseller to make a living from your words.

It’s just like when I got into engineering rock and roll music. Millions of kids dream of being a hit singer, and the competition is intense. Who dreams of being the sound engineer? I was able to walk in and go right to work keeping the shows running. So what if I didn’t sing.

Many people believe you get a job in academia by going to college, getting a doctorate, and then applying for work. In my case, my academic appointments at William & Mary and then at Landmark College were a direct result of the power of my written words. No doctorate was involved. That may seem unusual today but 100 years ago it was common. Words have a power that transcends more ephemeral things like a college degree. A degree cannot convey your powers of reason the way your words can.

People ask what my next book will be. I expect I have more to say, but at this time I don’t have a topic. I do have ideas. Whatever I end up doing, know this: Any book I write will be made possible by the money and security I have derived from writing seemingly pedestrian things all my life. If you want to be a writer, that is the path to success. Don’t try to write a bestseller. Be a tradesman with your words, and write what is useful and build a life around it.

Sometimes success in writing isn’t what you think it is. Writing is what got me where I am, but not in most direct manner.

John Elder Robison

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder RobisonDecember 13, 2020

Reflections on 2020

December 13 - It’s hard to believe 2020 is coming to an end. In Decembers past I sometimes assembled photos of places I’d visited. Prior to the pandemic, I spent a dozen years on the road, sometimes traveling 120,000 air miles in a year. This January started like many others. We spoke at some events in Florida, and Cubby came along to visit the alligators at Wakulla and my aunt and uncle from Cairo, GA:

This year, it all came to a stop.

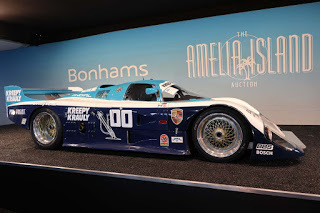

It was early March when I took my last trip. Covid was in the news every day, and borders were closing. But there was no sense of trouble when I flew to Florida for the Amelia Island car show. I had a job to do – @RobisonService had a Ferrari and a Corvette entered in the Bonham’s auction, and I went to represent them.

In the few days before the show, everything changed. Amelia is a big show and a lot of people fly in to attend it. Our borders closed, and Europe was already locked down. Hotel rooms were suddenly empty. At the show field, some people eyed each other warily, wondering who might carry a deadly infection. Others were happy to see their friends. Here I am with Ferrari expert Marcel Massini:

The front rows of seats at the auction are generally reserved for the big bidders, and many of the seats lay empty. You could sense the uncertainty in the air as the auction started. Bids for most cars were far below projections. Many people walked out with the sense that markets were in free fall. The stock market certainly gave that impression.

In a matter of days, airports all over America fell silent. The crowds vanished and planes sat idle or flew empty. We were consumed by worry and fear for the future. Two weeks later, the governor of Massachusetts ordered a statewide shutdown and our company’s parking lot emptied out, almost as quickly as the airports. Almost as an aside, the phones stopped ringing and our stock portfolios were down almost 40%.

Anyone who was around in 2008-9 has seen this play out before. Over 33 years in business we’ve seen a few downturns. One thing I’d learned is that most of us don’t live or die by the markets or the auctions. It does not matter what your assets are worth as long as they continue making you a living. I wasn’t planning to sell my stock or my company; what mattered was getting through a down time.

As a seller's agent it felt like the spring auctions were awful, but there are always two sides. Other clients have been buyers, and they have been sending a stream of jobs our way.

I write about the unusual cars we restore and take to shows because those are what interest me, but we do other things at my workplace. Robison Service is part of the Springfield Automotive Complex, which is home to a state inspection facility, a general car repair shop, a detailing shop, an undercar and alignment shop, and an ambulance garage for Springfield and surrounding towns.

With all those activities we were one of the businesses designated essential, and we never closed. We did furlough some workers, and I worked from home for a time, but we were lucky. By summer businesses were re-opening and work returned to the complex.

It has still been a hard year. Quite a few of our clients got sick, and a few died. Several workers in our complex became ill, but all recovered. My neighbor at work was diagnosed on a Wednesday, and died the following Monday. With 5,000 new cases being called every day in Massachusetts, we are in the thick of it.

Every day I am grateful for our staff, who have stuck together and kept the place going. I am grateful for our clients, some of whom saw we were slow, and sent more work to keep going. I am grateful for our bankers and our suppliers who ensured a flow of funds and materials to keep operations running as smoothly as possible. The work photos are from better days, when we didn't have masks, social distancing, and more . . .

It has been a year of many challenges, but we are still standing as we near the end.

One thing this pandemic has shown me is that a part of me will always be here at the car complex. I’ve had the great honor of traveling the world to speak about autism and neurodiversity, and I have been able to play a role in establishing policies to help our community. I’ve even followed in my parent’s footsteps teaching neurodiversity in college.

But in what seems like the blink of an eye, beginning in March, all those activities shut down or transformed. A dozen speaking engagements just evaporated. Autism conferences like INSAR were all cancelled. College went online, and I found myself struggling with Zoom to engage with students. I am forever grateful to the Arnow and Olitsky foundations for keeping neurodiversity programs going in this challenging time.

My college teaching appointments are something I am proud of, but they don’t pay enough to live on. It is the car complex that has sustained me – and everyone else who works there – through this most challenging of years.

I’m doing some online neurodiversity work, and I hope to travel again in 2021, but this pandemic has shown me the great value of being right here in Springfield with the cars and the people that have been part of my life, since long before I knew anything of autism.

2020 has certainly made me rethink my priorities. I’m sure many of you feel the same

As we go into the holidays I wish all of you well and hope for a better years for us in 2021.

Meanwhile, here are some photos that show 2020 through my eyes.

Best wishes

John Elder Robison

Sights from Wakulla:

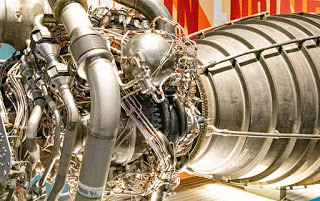

An engine

This Continental SC will be in the spring issue of the Flying Lady - look for it there

Rocket engine

With Stephen Olitsky and Ernie Els . . . in the last weeks of pre-pandemic freedom

A Rolls Royce Phantom at work

Welding a frame for a 60s Maserati V8 - we have three here for overhaul now

The woods at home

There are probably not 100 Alfa Romeo Montreals in the USA

We were proud to send this NAS Land Rover Defender 110 home to upstate New York this summer

A rare Peugeot 404 convertible at @RobisonService

Night moves - a Bentley on the transport trailer

April 8, 2020

Possible Autistic Vulnerability to COVID-19

Over the past 20 years we have made some progress understanding the biological underpinnings of autism, and by extension, ADHD and other related neurodevelopmental conditions. We have long known of links between autism and dysregulation of the immune system. One marker of that is abnormal cytokine levels found in some autistic people.We don’t know if the immune dysregulation leads to development of different brain wiring, or if our different brain wiring leads to immune dysregulation. It’s also possible there is some factor common to both, making immune dysregulation and autism (in some people) both by-products of some lower level difference. One reason I advocate for basic research is to answer questions like that. While autism itself if not physically life threatening, immune dysregulation is. When the two are intertwined as they are in many autistics, it presents a medical threat we need to address.

As further evidence of immune dysregulation in autistics, we know many of us have co-occurring medical problems that are also tied to immune dysfunction. Those conditions range from allergies and sensitivities to asthma to diabetes. GI problems – one of the most widely discussed co-occurring problems for autistics – also have an immune dysfunction connection. While we don’t know how those conditions are intertwined, the fact that they are – for many people – is undeniably real.

One thing we’ve learned is that autism is a very heterogeneous condition. In other words, at a biological level, there is no one “key to autism.” Rather, there are thousands of things that interact in complex ways to produce the behaviors we call autism. Therefore, while immune dysregulation may be a big issue for some autistic people it may have zero impact for others. We do not know why, or who’s in one group and not the other.

In recent years scientists have worked to understand the connections. One area of focus has been abnormal cytokine response. Cytokines are small proteins used by the immune system. In a 2018 article from Frontiers in Neuroscience, several scientists from the UC Davis MIND Institute describe the connections.Most lay people had never heard of cytokine responses when that article was published. Anyone who reads about the ways COVID-19 can turn deadly can’t miss the term now. Doctors ascribe deadly lung and organ damage to “cytokine storms” that occur when a patient’s immune system goes wild in response to infection and the body attacks itself.Early in the pandemic doctors observed poorer outcomes in hospitalized people with cognitive disabilities. Most doctors attribute this to the many known reasonsIn the progression of COVID-19 there seems to be a window during which disease is mild, and then it comes roaring on with respiratory failure (possibly attributed to the body’s immune response). Some doctors have tested for elevated levels of IL-6 prior to onset of respiratory failure, and when it was high, treated with suppressant drugs with very good results.

Are autistic people a group that should be particularly focused on this issue? No one knows, because there has not yet been time to study the issue. Given the uncertainty, and the high risk of death after COVID-19 respiratory failure, autistic people in that position would be wise to ask the question of their doctors. IL-6 levels can be tested in most hospital settings and suppressant drugs are widely available.

There is more and more emerging evidence that sharply elevated IL-6 levels foretell respiratory failure in COVID, but so far no one has speculated who might be prone to this, or why.

There is other evidence that autistic people may be more vulnerable in a general sense. The Adverse Child Experiences studyAny autistic person who is hospitalized with COVID-19 would be wise to inform doctors that they have autism, and autism may be tied to immune dysfunction, and they may be vulnerable to abnormal cytokine responses as revealed by a test of IL-6 levels. The relationship between other neurodivergent diagnoses (ADHD, for example) and immune dysfunction is less clear but remains a possibility. You should also advise doctors that autistic people may not sense things in their own bodies and may be less aware of deterioration; closer monitoring is advisable.

In this article, I am not proposing treatments. There is no home remedy for this, and nothing you can do today to protect yourself beyond the social distancing steps we are all taking. Instead, I am offering very specific advice about tests and monitoring you can request for a hospitalized autistic person suffering from COVID-19. You should discuss the test results and possible actions with the doctors. I offer this advice because performing such tests may be far from the minds of most admitting physicians yet for some of us it may be a lifesaver.

I wish there were time to test these hypotheses better, but for some of us, the wolf is at the door right now. For others, he will spring tomorrow, or the next day. If we – as a group – are vulnerable to cytokine storms in this situation, the advance knowledge can be critical. The downside – the possibility of wasted tests – seems small.

There is always a risk when suppressing the immune system in a sick person. But the efficacy of that is currently being explored by many doctors treating COVID today; it is not a new suggestion I am advancing. I have written elsewhere about the psychological threat the COVID-19 pandemic presents for autistic people. This possible medical threat is one more thing to consider.

My best wishes to everyone in this difficult time

John Elder Robison

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

March 22, 2020

Thoughts on #Coronavirus risk

As an autistic person the best thing I can offer by way of calming is some logic and reason, based on good facts.Our country's failure to expand testing has created the perception that there may be thousands or millions of undiagnosed, non symptomatic cases lurking. The evidence isn't bearing that out. Massachusetts is ramping up testing fast, from 50 tests a day two weeks ago to 1,000 tests a day now. Currently the tests are only done on people that doctors suspect may be infected. But 90% of the tests are coming back negative. Consider what that says: Most of the people who think the have coronavirus, or are suspected of having the virus by doctors, don't. No matter where you are, you are likely to suspect virus is lurking unseen within you or the next person you will see. The current odds to not bear that out. At this time, the fear is worse than the reality.We say air travel carried the virus around the globe. But look at who got sick - passengers in adjacent seats. Not flight attendants. Not whole planeloads of people. That strongly suggests that the virus is mostly transmissible over short distances - 2-3 feet. There is no surge of cases among airline stall, all of whom walk the aisles. So that argues that social distancing works.News stories focus on the total number of cases, without considering that most people recover, and the number of ACTIVE cases is much lower and growing slower that the scarier total number some reporters like to present. While reporters tend to focus on the rate new infections are reported, that number may grow faster as we ramp up testing efforts. A more significant number is the daily death rate. When that slows and begins to decline we will be topping the curve even if that's not apparent in the new infection statistics.In Boston we had a big bunch of cases that emerged from the Biogen conference where large groups were packed for hours in conference rooms with a few infected people. We have learned from that. For many of us, we are not that close to people now and we are not next to them for hours.Even in families when one member gets sick it is not a foregone conclusion everyone else gets it. That rate is actually under 40%. That gives hope also that this virus is not so incredibly contagious that we are all destined to get it in a matter of weeks, as some alarmists predict. If our social distancing slows the spread, hospitals will not be overwhelmed, and care will be there for the population who really need it. Finally, with all the focus on deaths, the fact is, more than 96% of the people diagnosed with coronavirus recover fine. Since we know there are some folks who get mild cases and never get tested, the survival rate is probably higher. Therefore, if you do get it, odds are still on your side.Sure, you may have risk factors like age, diabetes, heart issues . . . but you can also take steps to reduce risk, like the social distancing and staying home and out of physical contact. Given the number of people who don't take protective measures your own actions may well more than offset risks from age and other conditions. As always, we have options to influence what happens. Our individual outcomes are not preordained. Risk factors do not equal "being doomed." There are always two sides to these things. Those are some facts to consider and discuss.

Best wishes in a trying timeJohn Elder Robison(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

March 1, 2020

The Limits of Neurodiversity

Human diversity emerges as a result of genetics and environment. There is a large heritable component to some neurotypes, just as body shape tends to run in families. But it’s not all genetics. Environmental factors also influence human development. Diversity is also driven by evolution as many traits confer situational advantages, but it’s always a balance as “too much” or “too little” shades from difference into disability.

The continuum of neurological function includes people with many different cognitive traits. Memory, emotional sensitivity, ability to focus on a task, mathematical ability . . . all those things vary, as does general intelligence. Emotional intelligence has long been recognized and we are now seeing it is on a continuum with logical intelligence at the other end. In other words, some people are governed by emotions while others, in the manner of Star Trek’s Spock, are logical.

During the twentieth century psychiatrists gave diagnostic labels to cognitive traits that had been observed for a long time, but not pathologized with a diagnostic label. Happy or sad were long-recognized states of mind; psychiatrists recognized extremes of these behaviors with terms like manic or depressed, and they created formal labels like “major depressive disorder.”

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) became the medical term for something parents called “bouncing off the walls.” Being withdrawn into oneself, having a limited range of interests, and having an impaired ability to connect with and engage others became autism, or autism spectrum disorder. The extreme logical thinker may exhibit traits of autism while the extremely emotional person can manifest traits of schizophrenia.

For several decades following their introduction, terms like ADHD or autism were only used to describe people with severe, profound impairments. Those labels were bestowed on children whose behavior was far different from that exemplified by most kids. Since differences existed on a continuum it was up to the trained professional to determine when simple difference became pathology.

Whatever one calls it, the range of neurological function, encompassing both typical and abnormal behavior, observed across a number of domains, describes human neurological diversity. That is neurodiversity, but neurodiversity is also more. . .

Neurodiversity has also become an identity; when individuals who had received psychiatric diagnoses wanted to identify themselves in non-medical terms. They felt they were “more than a diagnosis,” and believed medical labels pathologized them or carried stigma. Soon the word neurodiversity was adopted by others who lacked a formal diagnosis but still felt “different.” For them, the term was not assertion of a medical condition, or an attempt to claim disability supports, but rather a way to center themselves in the world.

In the neurodiversity worldview people whose neurology is “average” are called neurotypical. People whose neurology differs from average; i.e., having traits of autism, dyslexia, or ADHD, are neurodivergent. Neurodiversity is the term for the continuum, and the population may be called neurodiverse. While that seems straightforward, it implies “one way or the other” that does not exist in real life. Psychologists agree there is no such thing as “typical” – we are all individuals.

Therefore, thought leaders now question the use of the terms neurodivergent and neurotypical. They argue that neurotypicality is an invalid concept since there are no people who have been tested and found to be “midrange” in all cognitive dimensions. Instead, each of us has a mix of strengths and weaknesses, and since we are not generally tested, our abilities are only guessed at. Therefore, neurotypical is merely a rough approximation even as the population is undeniably neurodiverse. No one word defines us; individuals are best described by their specific traits or even by support needs.

Neurodiversity is therefore a biological fact and also a term of identity. When someone identifies as having autistic traits in the context of neurodiversity, they are not generally seeking medical supports or disability accommodation though they may also seek those things through formal diagnosis. Rather, they seek a sense of community by identifying with what they believe is a like-minded group.

Self-diagnosis of autism or ADHD is controversial but anyone is free to embrace the neurodiversity paradigm and say they are “different” because they are not assuming a formal medical label.

In terms of identity, most who identify with the neurodiversity paradigm see themselves as different, not disordered. They may also feel disabled, or disabled and exceptional. They generally perceive their neurological diversity as part of healthy human diversity. However, not all people feel this way about neurodiversity. Some feel so disabled, or suffer to such an extent, that they reject the neurodiversity paradigm for themselves. They describe themselves as sick, damaged, or injured.

That difference in views may be expressed thusly: At its extremes, difference becomes disability. While the point of transition varies from one person to another, there is always a point where healthy difference becomes pathology or disorder.

Studies have shown that most people judge themselves to be less disabled, even as observers think they are more disabled. In most cases disability is in the eye of the beholder. An exception would be in the world of work, where a person might not think of themselves as disabled, but they might not be able to complete certain work tasks on time or at all.

Neurodiversity as a biological fact applies to everyone. Neurodiversity as a term of identity applies to many people, but a significant number who feel disabled reject the neurodiversity paradigm. That is one limit of neurodiversity.

Schools and workplaces are fast developing neurodiversity programs, with a view to accommodating a wider range of people in schools and in jobs. That is a laudable goal, and an array of supports will no doubt allow people who have been excluded from work or school in recent years, to participate. Neurodiversity programs with intensive supports and a social welfare model – like Project Search – will help a number of people who are too disabled for other programs.

Beyond that there remains a portion of the population whose cognitive differences limit engagement in school and preclude transition to work. They may not be able to communicate effectively, or they may have significant cognitive impairments. They may have medical complications like epilepsy that compromise quality of life. Critics of neurodiversity express the fear that broad adoption of the neurodiversity paradigm renders such people invisible.

In this writer’s view, that need not happen. Programs to support less disabled people should come at the expense of programs for the more disabled. Disability support is not a zero-sum game. Neurodiversity – whether as neurological fact or social identity – should not be perceived as denial of profound cognitive disability in its many forms. Neurodiversity is a way for people to identify themselves, but some people are so disabled they cannot do that, and they cannot rightly be called anything but seriously disabled.

John Elder RobisonMarch 2020

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

September 4, 2019

Neurodiversity, Disability, and Exceptionality

This six minute video of my convocation talk at Landmark College really encapsulates my thinking on neurodiversity.

We can have disability diagnoses, but we do not have to live as disabled people, thereby internalizing the idea we are "less" than others. We can choose to live as neurodivergent people - using a term that springs from our own community - and recognize each of us has a mix of disability and exceptionality.

Watch the video and tell me what you think:

John Elder Robison(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison