Devdutt Pattanaik's Blog, page 3

April 1, 2019

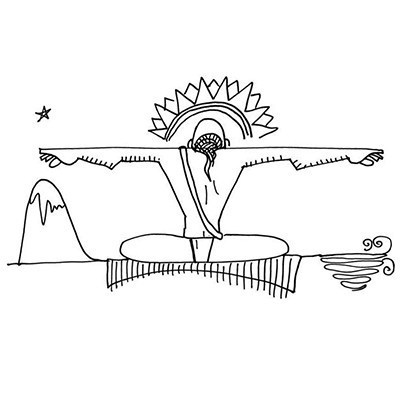

Left is north, right is south

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 31st March, 2019, in Mid-day

When one faces the rising sun, the back faces the west, the left hand represents the northern side and the right hand represents the southern side. In Hindu mythology, the left hand is called the Vama-patha or the path of the left hand, which is associated with Tantra. However, the right hand is not called the path of the right hand, but is called the southern path: Dakshina-patha, which is the right-handed path or the orthodox Vedic path. In politics, right stands for those who value traditional hierarchy (much like Vedanta) and left stands for those who overturn structures (much like Tantra).

The northern direction is associated with Shiva, but the northern path or the left hand is associated with the goddess Shakti. The southern direction is associated with death, but the southern path is associated with Vedanta, which talks about immortality. Why is north associated with Shiva and immortality and why is south associated with Shakti and death? That is a question to ask.

The north is marked by the still Pole Star. It is also the direction of the eternal Himalayas. Mountains have long been seen as symbols of permanence. And so, the still and permanent north best symbolises the north. The rivers flow south and lose their identity as they mingle with the sea, which makes south the direction best suited to represent death. In villages across India, the crematorium is usually placed in the south. Directions are thus turned into metaphors. They are not to be taken literally.

In the Ramayana, Ravan, who lives in the south in the middle of the sea, embodies the idea of death; his home is not the literal south. He goes to the North to Shiva and tries to bring Shiva to the south, but fails. The Shiva-linga now rests at Gokarna, in Karnataka. In his compassion, Shiva allows his son Kartikeya, and his student Agastya, to move south, where they are worshipped as the primary deity Murugan and the primal teacher of the Siddhas. Ram makes his journey south and then returns north; Ravan’s brother Vibhishan tries to get the image of Vishnu, from Ram himself, to the south; he, too, fails. The image now rests at Srirangam in Tamil Nadu. Shiva, who faces south, is called Dakshinamurti, the hermit-teacher. He faces Dakshina-kali, his beloved Shakti, who comes to him from the south to transform him into a householder.

If north, by virtue of Pole Star, is linked to permanence, east by virtue of the rising sun is linked to growth. So, the morning begins by facing the rising sun. In Vedic times, the priest sat facing the rising sun and placed the fire in the east. But when temples were built, the image of the deity was placed to face the rising sun and so the devotee faced the west to see the deity lit by rays of the glorious rising sun. The rising sun has always been an awe-inspiring deity to be worshipped. The setting sun is a tourist attraction, a metaphor for life. We celebrate those whose careers are on the rise and watch vicariously those whose careers are on a downward spiral.

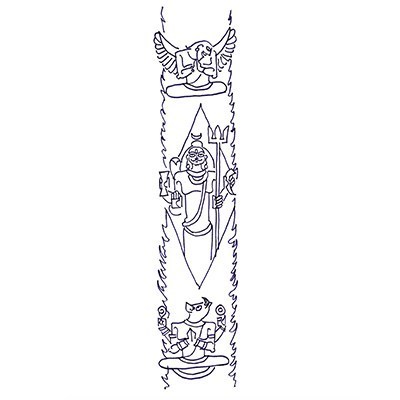

The pillars of gods and kings

Published on 31st March, 2019, in Mumbai Mirror

Published on 31st March, 2019, in Mumbai Mirror

The Rig Veda refers to giant houses with many pillars. However, we have no archaeological evidence of them, because the material used was probably wood. In the Atharva Veda, we hear of the stambha, or pillar, that separates Heaven and Earth. Even today in traditional Hindu temples, a pillar stands in front of the temple, either for the flag, or for lamps, or to simply assert divine authority.

Pillars have played a very important role in cultures around the world to reflect both religious as well as political ideas. Some of the earliest pillars of the world are found in Egypt, where they are known as obelisks. They are clearly of religious significance as they are placed before temples. They embodied virility of the God-king that ensured prosperity of the land. The earliest political pillars are found in the Middle East; they were set up by Persians kings.

It is believed that under Persian influence, Ashoka set up India’s first pillar commemorating his kingship. Legend has it that Ashoka built 84,000 pillars to mark the 84,000 relics of Buddha in different parts of India. Only a few of these survived with his edicts. These functioned both in a religious as well as a political capacity. These were free-standing pillars, unlike pillars that hold up the ceiling of a house. They were topped by images of royal symbols such as the lion, the bull, the horse or the wheel.

India’s first purely religious pillar is around 1,900 years old. Called the Garuda Pillar, it is in Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh, and was built by a man called Heliodorus, who was the Greek ambassador to the Shunga kings. Then there is the delightfully brilliant Iron Pillar, built by Chandragupta I, of the Gupta Dynasty, nearly 1,600 years ago. It stands in Delhi. What is unique about it is that, although it is made of iron, it has not rusted over time.

There are temples in India, especially in the south, like the Madurai Meenakshi, which have thousandpillared halls. Besides being exquisitely carved, many of these pillars also make various musical sounds. Every temple today has a Dhwaja Stambha in front of the sanctum sanctorum or the Kirti Stambha. These are also found in Jain temples, often topped by images of gods who salute the Jain Tirthankaras.

It is important to mention how the idea of the pillar as a symbol of power was exploited in Puranic stories. Pillars establish the idea that God is greater than any king. They also connect kingship with divinity, for in ancient architectural manuals, it is clear that the house of God is also the house of the king. Early temples were not distinguished from royal palaces. As Puranic Hinduism established itself in India over the last 2,000 years, the story of Shiva’s pillar and Vishnu’s pillar was retold.

Shiva’s pillar is made of fire. Its beginning and end cannot be seen. Brahma took the form of a swan to find its top and Vishnu took the form of a boar to find its base. Both were unsuccessful. The pillar becomes the ultimate axis mundi, or the centre of the world, connecting the three worlds together. Every Shiva linga is considered a diminutive double of this cosmic, infinite pillar. In many Shiva temples such as those in Ujjain and Trimbakeshwar in central India, we find Deepa Stambha, or the Pillar of Fire, where a thousand lamps are lit to recreate the primal pillar of fire that was first seen by Brahma and Vishnu.

In the Vishnu Purana, the arrogant asura king, Hiranyakashipu, refuses to believe that God is everywhere. Hiranyakashipu smites a pillar of his palace. Vishnu emerges from the broken pillar, in the form of a man-lion, Narasimha, and kills Hiranyakashipu. In this story, the power over kingship is clearly established. God is greater than an earthly king, being able to break the pillars that kings set up to declare their royal authority.

In modern times, we see pillars being replaced by statues to establish political power across the country. When we see these statues, it is time to remember the story of Shiva and Vishnu and humbly realise that, no matter how powerful human beings may be, there is, always, a power above them that can stretch to infinity and shatter any proud pillar to smithereens.

March 25, 2019

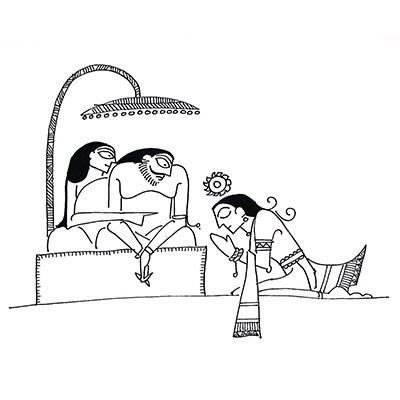

What came first: the world or life?

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 24th March, 2019, in Mid-day

As per scientists, the world began 13 billion years ago with the Big Bang. Earth came into being about 5 billion years ago. And about 4 billion years ago, life emerged on Earth. What we mean by ‘life’ is the appearance of sentience, the appearance of organisms, who can ‘sense’ the world around them. In other words, the appearance of a mind. So, from a scientific point of view, matter comes first, then mind; the world comes first, then life; the world of physics precedes the world of biology.

In Puranic metaphor, mind is male and matter is female. The world begins when Vishnu ‘wakes’ up. Thus, creation does not mean the creation of material world, but the awareness of the material world by the mind. This Hindu story of creation is very different from the biblical concept of creation, in which god creates the world in six days, with life on the third day. Creation in Hinduism is psychological, not physical; it is about awareness of matter not appearance of matter.

The earliest organisms to appear are focused on survival and do not ‘see’ the world as it is, but only as opportunity (food, mate) or as threat (predator, rival). Even plants and animals do not reflect on the nature of world. This starts only with humans. In Hindu mythology, this is explained as Brahma emerging from the lotus flower, frightened, lonely, unable to make sense of the world. He ‘sees’ a woman, who he claims to be his creation, so his daughter, and seeks to possess and control her, an act for which he is beheaded by Shiva. Brahma’s desire thus sets forth in motion the cycle of life: he becomes creator, and Shiva, who stops his desire, becomes destroyer. This again is not creation or destruction of the world, but creation and destruction of ‘desire’ or ‘hunger’, the forces that propel life. Brahma creates life, not world, by submitting to desire; Shiva destroys life by destroying desire. Brahma is bhogi, Shiva is yogi.

Vishnu is preserver. From his navel rises the lotus that gives birth to Brahma. He understands Brahma’s ignorance. He maintains life by restraining Brahma’s desire as well as Shiva’s rejection of desire. If Brahma is a householder who seeks a wife, and Shiva is hermit who rejects marriage, then Vishnu is the hermit-householder, living in a household without getting attached to anything. Again, this is a psychological state, not physical.

The goddess embodies the physical side of the universe. She is matter. She is the world that exists before life comes and even after life goes. In other words, she exists before Vishnu wakes up and even after Vishnu goes to sleep. She is mother from whose womb life is created and daughter who is created in the mind of humans. As mother she is objective reality; as daughter she is subjective reality. Thus, Brahma’s incest is not to be taken literally; it is a metaphor for our attachment to the world we imagine.

This complexity of Hindu Puranas was dismissed as gobbledegook by colonial translators in the 19th century. Hindus also could not explain the metaphorical nature of their scriptures, why metaphor (rupak in Hindi) is needed for mind and all things psychological that has no form (rupa in Hindi). For Orientalists, the natives of India were too inferior to think in metaphorical terms, a contemptuous attitude seen even today among scientists, who dismiss knowledge systems of traditional and tribal societies. Our ego stops us from appreciating other people’s language. We behave as Brahma, assuming the goddess is our dominion, and that is a tragedy.

March 22, 2019

How India lost its rich maritime tradition to Europeans

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 22nd March, 2019, in Economic Times

Sea travel is mentioned in the Buddhist Jataka tales but not in the great epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, perhaps because the former was patronised by mercantile communities (vaishyas) and the latter by landed gentry (kshatriyas).

Sailors from India travelled along the monsoon winds to Southeast Asia and to Arab countries to trade on fabrics and spices in exchange for gold. We do know that Indian sea trade was widespread even during the Harappan Era. The sea was used to trade with the Arab coast. India was then known as Meluha.

2000-year old Tamil literature refers to merchants who travelled far and wide and brought back great riches including Roman coins, Roman wine and even Roman women. In Southeast Asia, sea merchants travelled to countries like Indonesia, Cambodia and Vietnam. They carried with them not just trading goods, but stories, which is why in these regions we find the retelling of the great epics, Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

Along the sea coasts of India and SouthEast Asia, one finds shadow-puppetry, telling the stories of Ramayana and Mahabharata. These were supposed to have been invented on ships, sailing to Southeast Asia, with the light of the flames, casting shadows on the sails of the ships.

Hero stones found in Goa dating between 10th and 11th centuries do show seafaring boats. But in the grand temples of the South, boats are conspicuous by their absence, even though the Chola kings had a great navy. One does see images of kings and gods taking boat rides in the terracotta temples of Bishnupur in Bengal dating 17th century; but most of these boats are usually on ponds and rivers and lagoons, not the kind of great boats that travel across the sea.

In Gujarat, near Khambat, we hear of Vahanvati Sikotar Mata also known as Harsiddhi Mata, a goddess who protects sailors from shipwrecks. In Odisha, there is the famous folktale of Topoi whose seven brothers sailed to Bali for business. Baliyatra in Odisha involves floating toy boats in temple ponds, to remind people of the great seafaring merchants of Odisha.

Thus, we do see a coastal maritime tradition both in the eastern and western regions of India. However, the traditions changed about a thousand years ago. The sailing, which was done by Indian merchants, was outsourced to the Arabs.

Later, the Arabs were defeated by the Portuguese who took over the sea trade. Then the Portuguese were defeated by the Dutch and the British and we see the great conquest of the world, through the maritime tradition of Europe. And India’s maritime tradition is all but forgotten.

There were many reasons attributed to why India’s maritime trade declined. One reason was the tension between the Brahmins and the Buddhists. The sea traders patronised Buddhism and the Brahmins patronised the feudal land owners, the Kshatriyas who controlled the ‘kshetra’ or land. In every culture there has been tension between the landowning rich and the trading rich.

Over time a belief spread that when you cross the sea, you lose caste. Once the idea became popular, people avoided travelling over water, which, in turn, led to the decline of Indians travelling over the sea; they restricted their trading activities to the ports; communities in Kerala and Gujarat that insisted on travelling converted to Islam and forged marital relations with Arabs.

This also led to the decline of Hinduism spreading in South East Asia. Buddhists who had already migrated to Cambodia and Vietnam, created monasteries and taught local people Buddhism. Therefore, Buddhism thrived, in those countries.

Hinduism failed to flourish as Hindu priesthood was based on bloodline and castes, and since people could not travel across the sea or take their brides, across the sea, the Hindu tradition gradually waned.

This idea of people, travelling across the sea, becoming “polluted” and the taking away of caste came to be known as Kalapani. We know that even during World War I, soldiers who were sent by the British to fight in other parts of the world and returned home thereafter, faced great discrimination in their villages.

The one community that continued with shipping was the Chettiar community of Tamil Nadu. The Chettiars did travel, right from the time of Chola kings, establishing temples as far as China. The Chettiar community, it is said, worshipped Murugan, in his celibate form. Young sailor boys were told to maintain celibacy, when they travelled across the sea and only marry women of the community, otherwise they risked excommunication.

That the Chettiar community knew how to manage culture in the pursuit of economics is perhaps the reason of their business success.

March 17, 2019

Dharma is not a game of thrones

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 17th March, 2019, in Mumbai Mirror

King Nriga was cursed to be a lizard because he, without realising it, stole from one of his subjects. Nriga was known for donating cows to the sages of his kingdom. One of the donated cows slipped out of her master’s cowshed and returned to the royal cowshed. Since the royal cowshed had thousands of cows none of the royal servants noticed her return. Nriga then gave the same cow to another sage. When this sage was returning to his hermitage with Nriga’s gift, the first sage recognised his cow, claimed ownership over her, and accused the second sage of theft. When the second sage clarified that he had received it from Nriga himself, the first sage accused the king of theft.

“That cow was given to me. She is mine. Not the king’s. How then can the king gift her to another? This means the king stole my cow and gave the stolen cow to another sage. I accuse the king of stealing from his own subjects.” Investigations revealed what had happened. Nriga apologised to the first sage and offered to compensate him with a hundred cows. The sage refused. He wanted his cow back. Nriga then went to the second sage and offered to compensate him with a hundred cows. But the second sage refused to return his gift. For this act of hurting his subjects, albeit committed unintentionally, and quite accidentally, Nriga was cursed to turn into a lizard, and stay in this form until he met Krishna. Nriga accepted his punishment with grace.

This story is told by Bhisma to the Pandavas in the Anushasana Parva of the Mahabharata as he gives them lessons on raj-dharma, what makes a great king. A king is responsible for the happiness of his subjects. He is responsible for all the hurt he causes them, even without meaning to. This story is significant as Nriga is an ancestor of Ram, and from the much venerated Ikshavaku clan of the solar dynasty, which gave birth to many great kings, including several Jain Tirthankaras.

We live in times where politicians talk of Ram and Ram-rajya, but take no lessons on what raj-dharma meant to Ram and his Ikshavaku clan. They refuse to take responsibility for failures of their own governance. Quite unlike Ram, who, as per one oral narrative, despite being from the solar dynasty, called himself Ram-chandra, eclipsing his name with the moon to acknowledge his unfair treatment of his innocent wife Sita, who had been banished to protect royal reputation from public gossip.

We are told that the legendary king, Vikramaditya, renowned for his bravery, generosity and governance, also belonged to the solar dynasty. Many years after his reign, Bhoja wanted to sit on his famous throne, which had been discovered in the fields around his ancient kingdom. But when he was about to sit on this throne, the 32 statues of 32 yoginis who formed the base of the throne asked Bhoja if he had 32 qualities that made him as good a king as Vikramaditya. Bhoja cultivated these 32 qualities and only then sat on Vikramaditya’s throne. We live in times when no noble quality is required to be a king. Kingship is based on votes, and votes are won through emotional rhetoric, fanciful storytelling and false promises. More Natya-shastra and less Dharma-shastra.

Who do people turn to today, when kings are busy fighting enemies, real and imagined, or blaming corrupt kings of yore for all governance failures, and when tongues of even well-meaning vidushakas (court jesters who were also critics) are swiftly severed?

In the jungle, the strong feed on the weak. This is matsya nyaya (law of fishes), acceptable for animals, not humans. When humans behave so, it is adharma. In human culture, the strong have to take care of the weak. As per Manusmriti, gods created kings to establish dharma: to create an ecosystem where the weak can also thrive. In raj-dharma, the kingdom is more important than the throne. In rajniti, it is only the game of thrones; people don’t matter except for votes and taxes. Today raj-dharma is seen as idealistic and raj-niti (politics) is seen as more realistic.

For all the talk of Hindu revival, politicians refuse to accept this definition of raj-dharma. Insisting that the ‘system’ is the problem as the ‘system’ is designed for the strong. And so they spend time in raj-niti, helping the rich, who in turn help political parties accumulate funds secretly, so that they can sit on the throne, enjoying power without any responsibility or accountability, letting roads rot, and bridges collapse, knowing there is always someone else to blame. If today’s politicians lived in Nriga’s time, they would change the media narrative and declare the sages to be thieves and claim the cows for themselves.

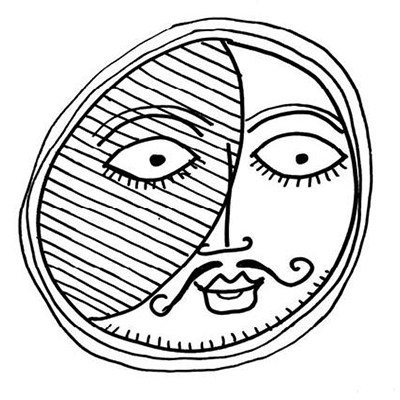

For the love of the moon

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 17th March, 2019, in Mid-day

In Hindu astronomy, the sky is divided into 28 parts, or nakshatras, based on 28 different constellations, one of which is supposed to have disappeared so effectively that there remain only 27. These constellations or houses are visualised as goddesses. It is said that the moon god was married to all of them, but he preferred only one of his wives, which is the reason the 28th wife disappeared. The remaining 26 complained to their father, who got so angry with the moon god for preferring one wife over the others, that he cursed the moon god with tuberculosis, kshyayrog or wasting disease.

The moon started to wane and he kept waning. When he was about to disappear, he prayed to the great god, Shiva, who, through the practice of yoga, created energy within him. He then could energise the moon, who started waxing again. Therefore, Ardhachandra, the half moon or the crescent shape of the waning phase of the moon, represents the moment between death and rebirth, and plays an important visual symbol in Hindu mythology. It represents Shiva’s power, who is often described as the god with the crescent moon on his locks. Oftentimes, Shiva is equated with the moon, its shifting phases reflecting his moodiness, its glow representing his beauty.

Another story of the moon god is that he fell in love with the wife of the planet, Jupiter. Jupiter is called Brihaspati in Hinduism. He is the guru of the gods of the sky or the devas. Brihaspati is an old man, serious and rational. He lacks the passion found in Chandra, who is the most handsome of all gods and is associated with emotions, romantic desires and moodiness. Brihaspati’s wife, Tara, which also means star, grew bored of Brihaspati, and eventually eloped with Chandra.

This led to a crisis in the heavenly kingdoms, because Brihaspati went to Indra, the king of the sky, and demanded his wife be brought back. If Brihaspati did not perform any rituals for the devas, they were doomed to face defeat in battle. Indra had to fight Chandra and force him to let Tara go, who returned home pregnant, and everybody wondered whose child it was.

Tara refused to say anything. When asked, the child in the womb revealed he was a love child, born of the moon god. This angered Brihaspati so much that he cursed the child to be born as an androgynous being. At birth, this androgynous being was called Mercury or Budh, the child of the star goddess and the moon god. And therefore, Mercury is changeable, neither this nor that, both male and female.

This makes for an interesting story in Hindu mythology. We have a mercurial god, who is androgynous. We have a moon god, who is romantic and emotional, and who is punished for favouritism. We have planet Jupiter, who is associated with rationality and who is hurt that women prefer the heart over the mind. Thus, the stars, planets and celestial bodies were used to map the human mind by ancient poets and seers of India.