Corey Robin's Blog, page 104

March 13, 2013

I am not a racist. I just hate democracy.

So here’s a fascinating moment of right-wing self-revelation.

Last month, Sam Tanenhaus wrote a piece in The New Republic saying that American conservatives since the Fifties have been in thrall to John C. Calhoun. According to Tanenhaus, the southern slaveholder and inspiration of the Confederate cause is the founding theoretician of the postwar conservative movement.

When the intellectual authors of the modern right created its doctrines in the 1950s, they drew on nineteenth-century political thought, borrowing explicitly from the great apologists for slavery, above all, the intellectually fierce South Carolinian John C. Calhoun.

Progress, if you ask me: Tanenhaus never even mentioned Calhoun in his last book on American conservatism, which came out in 2009—though I do know of another book on conservatism that came out since then that makes a great deal of Calhoun’s ideas and their structuring presence on the right. That book, just out in paperback, got panned by the New York Times Book Review, of which Tanenhaus is the editor. Thus advanceth the dialectic. But I digress.

Writing in the National Review, Jonah Goldberg and Ramesh Ponnuru naturally take great umbrage at being tarred with the Calhoun brush. No one wants to be connected, by however many degrees of separation (Tanenhaus counts two, maybe three, I couldn’t quite tell), with a slaveholder and a racist.

But notice how they take umbrage:

Now Tanenhaus doesn’t want you to think he is saying that today’s conservatives are just a bunch of racists. Certainly not. He is up to something much more subtle than that. “This is not to say conservatives today share Calhoun’s ideas about race. It is to say instead that the Calhoun revival, based on his complex theories of constitutional democracy, became the justification for conservative politicians to resist, ignore, or even overturn the will of the electoral majority.” With that to-be-sure throat-clearing out of the way, Tanenhaus continues with an essay that makes sense only as an attempt to identify racism as the core of conservatism.

In the worldview of the contemporary American right it is a grievous charge—or at least bad PR—to be called a racist. But the accusation that you wish “to resist, ignore, or even overturn the will of the electoral majority”—that is, that you are resolutely opposed, if not downright hostile, to the basic norms of democracy—can be passed over as if it were a grocery store circular. Hating democracy, apparently, is so anodyne a passion that it hardly needs to be addressed, much less explained. Indeed, Goldberg and Ponnuru think the charge is Tanenhaus’s way of covering his ass, a form of exculpatory “throat-clearing” designed to make it seem as if he’s not making the truly heinous accusation of racism that he is indeed making.

So, that’s where we are. It’s 2013, and the American right thinks racism is bad, and contempt for democracy is…what? Okay, not worthy of remark, perhaps mitigating?

March 12, 2013

The US Senate: Where Democracy Goes to Die

Every once in a while I teach constitutional law, and when I do, I pose to my students the following question: What if the Senate apportioned votes not on the basis of states but on the basis of race? That is, rather than each state getting two votes in the Senate, what if each racial or ethnic group listed in the US Census got two votes instead?

Regardless of race, almost all of the students freak out at the suggestion. It’s undemocratic, they cry! When I point out that the Senate is already undemocratic—the vote of any Wyomian is worth vastly more than the vote of each New Yorker—they say, yeah, but that’s different: small states need protection from large states. And what about historically subjugated or oppressed minorities, I ask? Or what about the fact that one of the major intellectual moves, if not completely successful coups, of Madison and some of the Framers was to disaggregate or disassemble the interests of a state into the interests of its individual citizens. As Ben Franklin said at the Constitutional Convention, “The Interest of a State is made up of the interests of its individual members. If they are not injured, the State is not injured.” The students are seldom moved.

Then I point out that the very opposition they’re drawing—between representation on the basis of race versus representation on the basis of states—is itself confounded by the history of the ratification debate over the Constitution and the development of slavery and white supremacy in this country.

As Jack Rakove argued in Original Meanings, one of the reasons some delegates from large states ultimately came around to the idea of protecting the interests of small states was that they realized that an equal, if not more powerful, interest than mere population size bound delegate to delegate, state to state: slavery. Virginia had far more in common with South Carolina than it did with Massachussets, a fact that later events would go onto confirm. In Rakove’s words:

The more the delegates examined the apportionment of the lower house [which resulted in the infamous 3/5 clause], the more weight they gave to considerations of regional security. Rather than treat sectional differences as an alternative and superior description of the real interests at play in American politics, the delegates saw them instead as an additional conflict that had to be accommodated in order for the Union to endure. The apportionment issue confirmed the claims that the small states had made all along. It called attention not to the way in which an extended republic could protect all interests but to the need to safeguard the conspicuous interest of North and South. This defensive orientation in turn enabled even some large-state delegates to find merit in an equal-state vote.

As Madison, a firm opponent of representation by states, would argue at the Convention:

It seemed now to be pretty well understood that the real difference of interests lay, not between large and small but between the Northern and Southern States. The institution of slavery and its consequences formed the line of discrimination.”

True, Madison made this claim in the service of his argument against representation by states, but for others, his claim pushed in the opposite direction: a pluralism of interests in an extensive republic was not, as Madison claimed in Federalist 10, enough to protect the interests of a wealthy propertied minority. Something more—the protection of group interests in the Senate—was required. (Which is why, incidentally, I’m always amused by conservatives’ at the notion of group rights: what do they think the Senate is all about if not the protection of group rights? This is not to say that there aren’t principled reasons to oppose group rights; I’m commenting merely on the scandalized tone of the opposition.)

And when one considers how critical the Senate has been to the protection of both slavery and Jim Crow—measures against both institutions repeatedly passed the House, only to be stymied in the Senate, where the interests of certain types of minorities are more protected than others—the distinction between race and state size becomes even harder to sustain. Though the Senate often gets held up as the institution for the protection of minority rights against majoritarian tyranny, the minorities it protects are often not the powerless or the dissenters of yore and lore.

Indeed, for all the justified disgust with Emory University President James Wagner’s recent celebration of the 3/5 Clause, virtually no one ever criticizes the Senate, even though its contribution to the maintenance of white supremacy, over the long course of American history, has been far greater than the 3/5 Clause, which was nullified by the 14th Amendment.

This is all by way of a long introduction to a terrific article in the New York Times by Adam Liptak on just this issue of the undemocratic nature of the Senate, and some of the racial dimensions of that un-democracy. Just a few excerpts:

Vermont’s 625,000 residents have two United States senators, and so do New York’s 19 million. That means that a Vermonter has 30 times the voting power in the Senate of a New Yorker just over the state line — the biggest inequality between two adjacent states. The nation’s largest gap, between Wyoming and California, is more than double that.

The difference in the fortunes of Rutland and Washington Counties reflects the growing disparity in their citizens’ voting power, and it is not an anomaly. The Constitution has always given residents of states with small populations a lift, but the size and importance of the gap has grown markedly in recent decades, in ways the framers probably never anticipated. It affects the political dynamic of issues as varied as gun control, immigration and campaign finance.

In response, lawmakers, lawyers and watchdog groups have begun pushing for change. A lawsuit to curb the small-state advantage in the Senate’s rules is moving through the courts. The Senate has already made modest changes to rules concerning the filibuster, which has particularly benefited senators from small states. And eight states and the District of Columbia have endorsed a proposal to reduce the chances that the small-state advantage in the Electoral College will allow a loser of the popular vote to win the presidency.

…

What is certain is that the power of the smaller states is large and growing. Political scientists call it a striking exception to the democratic principle of “one person, one vote.” Indeed, they say, the Senate may be the least democratic legislative chamber in any developed nation.

…

Behind the growth of the advantage is an increase in population gap between large and small states, with large states adding many more people than small ones in the last half-century. There is a widening demographic split, too, with the larger states becoming more urban and liberal, and the smaller ones remaining rural and conservative, which lends a new significance to the disparity in their political power.

The threat of the filibuster in the Senate, which has become far more common than in past decades, plays a role, too. Research by two political scientists, Lauren C. Bell and L. Marvin Overby, has found that small-state senators, often in leadership positions, have amplified their power by using the filibuster more often than their large-state counterparts.

Beyond influencing government spending, these shifts generally benefit conservative causes and hurt liberal ones. When small states block or shape legislation backed by senators representing a majority of Americans, most of the senators on the winning side tend to be Republicans, because Republicans disproportionately live in small states and Democrats, especially African-Americans and Latinos, are more likely to live in large states like California, New York, Florida and Illinois. Among the nation’s five smallest states, only Vermont tilts liberal, while Alaska, Wyoming and the Dakotas have each voted Republican in every presidential election since 1968.

The article is long, but it’s worth the entire read. A model of how good journalism can incorporate the insights of historical and institutionalist political science (and not just the number-crunching kind).

Update (12 pm)

A commenter at Crooked Timber reminded me of this great review by Hendrik Hertzberg of Robert Dahl’s book on the Constitution. Hertzberg quotes this line from Alexander Hamilton at the Convention that I wish I had remembered and quoted in my post:

As states are a collection of individual men, which ought we to respect most, the rights of the people composing them, or of the artificial beings resulting from the composition? Nothing could be more preposterous or absurd than to sacrifice the former to the latter. It has been said that if the smaller states renounce their equality, they renounce at the same time their liberty. The truth is it is a contest for power, not for liberty. Will the men composing the small states be less free than those composing the larger?

Update (12:30 pm)

Nathan Newman just posted the following comment on my FB page. I thought it was worth sharing:

Ran the numbers a few years ago and found that states representing just 11% of the population could elect the 41 Senators needed to block any legislation the other 89% of the population wanted to pass. It’s actually worse than that since you only need a majority in each of those states to elect those Senators– so the right 6% of the population could theoretically block any legislation they wanted. Just a crazy anti-democratic institution. The Constitution kick of sucks– yeah, I said it.

Nathan also co-wrote a great article a few years back on the relationship between slavery, the Constitution, and the Reconstruction amendments. Worth a look.

March 11, 2013

Wendy Kopp, Princeton Tory

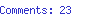

Going through some old files, I found copies of the Princeton Tory, which was Princeton University’s right-wing undergraduate magazine in the 1980s.

Today it bills itself as “a journal of conservative and moderate political thought.” Back in the day, the Tory ran articles in praise of abstinence and against the campus divestment movement (“Although Jerry Falwell’s claim that [Archbishop Desmond] Tutu is a ‘phony’ is exaggerated, it is true that he has little support within South Africa. The image of Tutu as a prominent figure is a creation of the international community”). It staged reenactments of Washington’s crossing of the Delaware. Nothing outlandish or outré; just a slightly fustier version of the campus right of the 1980s.

Most of the staffers were smart. Some, like the magazine’s founders Dan Polisar and Yoram Hazony, were scary: hardcore Zionists, Polisar and Hazony went onto storied if peculiar careers on the Israeli right; Hazony, once a close aide to Netanyahu, wrote a eulogy for Meir Kahane.

But what caught my eye as I was leafing through the magazine’s pages was a name on the masthead.

Wendy Kopp, in case you haven’t heard of her, is the founder and recently retired head of Teach for America (TFA), the controversial organization at the center of the country’s education wars. Diane Ravitch has been tangling with her for years.

Kopp came up with the idea for TFA while she was an undergrad at Princeton, and though its do-gooder image can seem at odds with the selfishness of the market, from the beginning Kopp has seen TFA as an emblem and instrument of capitalism and its hierarchies. With seed money from Mobil and Union Carbide (the public relations disaster of Bhopal still in its rear view mirror), Kopp announced in 1989 that “we really want to get the cream of the crop.”

Since I couldn’t find anything she wrote for the Tory, and their archive doesn’t go back beyond 2001, I have no idea what she was thinking when she joined it. She and I were in the same class at Princeton, and I met her in the first weeks of our freshman year (are you noticing a pattern to my past?) We worked together as stringers for newspapers and wire services across the country. But beyond her telling me, proudly and repeatedly, that she was a “corporate tool” (the phrase, I think, was just coming into vogue), I have no idea what her political views were.

March 9, 2013

The Smartest Guy in the Room

The current issue of Vanity Fair has a profile of William Ackman, the billionaire hedge fund manager who’s trying to bring down Herbalife. Ackman’s friends and enemies call him Bill; I know him as Billy.

You see, Billy Ackman and I grew up together in Chappaqua, New York. He was a year ahead of me in school. Our families went to the same synagogue. I knew his parents, and his older sister and my sister were in the same class. We weren’t friends, and he never made much of an impression on me. He was smart, but in the way many kids in Chappaqua were smart: he got good grades, obsessed about college, went to Harvard.

What I didn’t know was this:

In 1984, when he was a junior at Horace Greeley High School, in affluent Chappaqua, New York, he wagered his father $2,000 that he would score a perfect 800 on the verbal section of the S.A.T. The gamble was everything Ackman had saved up from his Bar Mitzvah gift money and his allowance for doing household chores. “I was a little bit of a cocky kid,” he admits, with uncharacteristic understatement.

Tall, athletic, handsome with cerulean eyes, he was the kind of hyper-ambitious kid other kids loved to hate and just the type to make a big wager with no margin for error. But on the night before the S.A.T., his father took pity on him and canceled the bet. “I would’ve lost it,” Ackman concedes. He got a 780 on the verbal and a 750 on the math. “One wrong on the verbal, three wrong on the math,” he muses. “I’m still convinced some of the questions were wrong.”

Ackman has made billions of dollars since 1984. According to Vanity Fair, he owns a $22 million mansion in the Hamptons, an estate in upstate New York, a co-op in a “historic” building on Central Park West, and a private Gulfstream 550 jet. He started his own hedge fund with a quarter-million dollars from Marty Peretz, who was his professor at Harvard (the only reason I could possibly imagine for taking a course with Peretz is that you think he might some day help you in just this way). He goes bone-fishing (whatever that is) in Argentina. He likes to say things like “Tennis, I practice. Presentations, I don’t.”— which I gather is hedge fund for “shaken, not stirred”—and “You know what? It’s time for me to do something for cancer.”

But with all that, he still remembers his SAT scores—and the number of questions he got wrong—as if he took them yesterday.

You see, Ackman is one of those guys for whom phrases like “smartest guy in the room” mean something. That’s a phrase I’ve been thinking about of late. I know smart people, but their minds are so various and incommensurate, it’d be impossible to rank them according to intelligence. They’re all smart, but in different ways: one sees deeply, one sees quickly, one sees things no one else sees.

But Ackman operates in a world—and it’s not just Wall Street; you can also find it in DC, the media, the law, and some parts of academia—where rankings of this sort mean something. They have to: no matter what the endeavor, someone always has to come out on top or in first. Whether it’s the most money, the biggest house, or the fastest cyclist.

It happened last summer when Ackman decided to join a group of a half-dozen dedicated cyclists, including [billionaire hedge-fund dude Daniel] Loeb, who take long bike rides together in the Hamptons. The plan was for Loeb, who is extremely serious about fitness and has done sprint triathlons, a half-Ironman, and a New York City Marathon, to pick up Ackman…The two would cycle the 20 or so miles to Montauk, where they would meet up with the rest of the group and ride out the additional 6 miles to the lighthouse, at the tip of the island. “I had done no biking all summer,” Ackman now admits. Still, he went out at a very fast clip, his hypercompetitive instincts kicking in. As he and Loeb approached Montauk, Loeb texted his friends, who rode out to meet them from the opposite direction. The etiquette would have been for Ackman and Loeb to slow down and greet the other riders, but Ackman just blew by at top speed. The others fell in behind, at first struggling to keep up with the alpha leader. But soon enough Ackman faltered—at Mile 32, Ackman recalls—and fell way behind the others. He was clearly “bonking,” as they say in the cycling world, which is what happens when a rider is dehydrated and his energy stores are depleted.

While everyone else rode back to Loeb’s East Hampton mansion, one of Loeb’s friends, David “Tiger” Williams, a respected cyclist and trader, painstakingly guided Ackman, who by then could barely pedal and was letting out primal screams of pain from the cramps in his legs, back to Bridgehampton. “I was in unbelievable pain,” Ackman recalls. As the other riders noted, it was really rather ridiculous for him to have gone out so fast, trying to lead the pack, considering his lack of training. Why not acknowledge your limits and set a pace you could maintain? As one rider notes, “I’ve never had an experience where someone has gone from being so aggressive on a bike to being so hopelessly unable to even turn the pedals…. His mind wrote a check that his body couldn’t cash.”

Apparently this story “is so widely known in the hedge-fund eco-system that it has practically achieved urban-legend status.” You might think people who make and break economies over breakfast would have something else to talk about. But when every last activity in life is a race, and someone must always win or lose, a weekend ride becomes just as much a revelation of the whole as a morning trade.

What’s odd in Ackman’s case is how loathed he is by his colleagues. So much so that they’ve banded together to take him down in this Herbalife deal.

Ackman says he suspected, when he “shorted” (i.e., bet against) Herbalife, that other hedge-fund investors would likely see the move as an opportunity to make money by taking the other side of his bet. What he hadn’t counted on, though, was that there would be a personal tinge to it. It was as if his colleagues had finally found a way to express publicly how irritating they have found Ackman all these years. Here finally was a chance to get back at him and make some money at the same time. The perfect trade. These days the Schadenfreude in the rarefied hedge-fund world in Midtown Manhattan is so thick it’s intoxicating.

So why is Ackman the object of such hate?

It’s Ackman’s perceived arrogance that gets to his critics. “The story I hear from everybody is that one can’t help but be intrigued by the guy, just because he’s somewhat larger than life, but then one realizes he’s just pompous and arrogant and seems to have been born without the gene that perceives and measures risk,” says [Robert] Chapman. “He seems to look at other members of society, even legends such as Carl Icahn, as some kind of sub-species. The disgusted, annoyed look on his face when confronted by the masses beneath him is like one you’d expect to see [from someone] confronted by a homeless person who hadn’t showered in weeks. You can almost see him puckering his nostrils so he doesn’t have to smell these inferior creatures.

Notice what Chapman says: Ackman treats his colleagues as if they were the homeless. In other words, it’s fine, even expected, to treat the homeless—and all the other little people—that way. As Ludwig von Mises wrote to Ayn Rand: “You have the courage to tell the masses what no politician told them: you are inferior and all the improvements in your conditions which you simply take for granted you owe to the effort of men who are better than you.” What’s not fine is to treat the big people that way.

Ackman’s mistake is that he takes the “smartest guy in the room” business too seriously. He really thinks he’s that dude. So much so that he’s willing to treat the other guys in the room as if they weren’t. That’s a no-no, and now they’re going to take him down for it.

Nietzsche understood this dynamic all too well. In an essay from 1872, “Homer’s Contest,” he remarked upon the centrality of competition to the Greek state. Not economic competition but other forms of contest: military, athletic, aesthetic, and so on. The idea was that “every talent must develop through a struggle” with one’s peers, but the point of that struggle was to serve the good of the state.

From childhood, every Greek felt the burning desire within him to be an instrument of bringing salvation to his city in the contest between cities: in this, his selfishness was lit, as well as curbed and restricted.

But when a competitor’s ambition is so unhinged, when he not only tries but actually manages to make his way to the top, and stay there, he must be removed. For the good of the state. That, says, Nietzsche, is the origins of the practice of ostracism. And if his competitors can’t do it, the gods will: they step in and take him out.

Why should nobody be the best? Because with that, the contest would dry up and the permanent basis of life in the Hellenic state would be endangered….the preeminent individual is removed so that a new contest of powers can be awakened: a thought which is hostile to the “exclusivity” of genius in the modern sense, but which assumes that there are always several geniuses to incite each other to action, just as they keep each other within certain limits, too.

Back to Wall Street: If the “smartest guy in the room” is going to serve the purpose for which it was coined—to spur little Billy Ackman’s to work hard, get into Harvard, and make lots of money—it has to remain an elusive prize. Something to strive for, never to be claimed.

No one, it turns out, can ever really be the smartest guy in the room. For two reasons. First, to make sure that everyone keeps fighting to get in, and stay in. Second, to make sure that everyone who doesn’t get in is kept out.

March 7, 2013

Guess How Much I Love You

We live in a country where, depending on which party is in control of the White House, some not insignificant portion of the population thinks it’s okay for the president to have the power to order extrajudicial killings simply because…they trust him. They like him. They can imagine having a beer with him. They like his wife. Her bangs. Their daughters. Or any one of a number of possible reasons of the republic.

And yet, writes Alma Guillermoprieto in the New York Review of Books, it is the Venezuelan people who are children, in thrall to a regressive fantasy of their dearly departed leader.

Perhaps in trying to evaluate the astonishing rule of Hugo Chávez the question to ask is this: whether the people he leaves behind regressed into a kind of childhood faith and dependency under his spell and what the price of such regression might be. Perhaps this is the state brought forth by those rulers we call caudillos—willful chieftans who rule by force of personality—of which Hugo Chávez Frías may have been the greatest of all. “There is no chavismo without Chavez,” he proclaimed repeatedly. Who now will dry Venezuela’s tears?

March 5, 2013

I Debate a Reagan Administration Official about Freedom and the Workplace

Last Tuesday, February 26, I debated Mark Blitz, a professor of political science at Claremont McKenna College and the Associate Director of the United States Information Agency under Ronald Reagan. Our topic: the politics of freedom. Our venue: lovely Linfield College in Oregon, where they have wonderful food and excellent conversation. Our host: Nick Buccola, who’s got a relatively new book out about the political theory of Frederick Douglass. Buy it!

Anyway, the debate got into some of the thornier questions of freedom in the workplace. Heated at some points, it was interesting throughout. With great questions from our audience.

March 4, 2013

The Wizard of Oz

Long before she became the doyenne of all thing social media, Laura Brahm wrote lovely, crisp prose on an array of topics: Arthur Koestler, memory and the Holocaust, the cultural Cold War, and more. And then, mysteriously, she stopped. Well, I’m glad to say she’s back. This time in the Nation, writing about Amos Oz’s and Fania Oz-Salzberger’s new book Jews and Words. Sadly, the article’s behind the paywall. Happily, I climb walls. Here are some excerpts:

Two millennia ago, some rabbis were having a debate. The details—involving dead snakes, a broken oven, a flying carob tree—were convoluted. Downright Talmudic, you might say, were the argument not already in the Talmud. God himself intervened, siding with one of the rabbis by performing a series of miracles. But divine intervention isn’t why the episode was remarkable. Rather, it was how the other rabbis responded. “When scholars are engaged in a halakhic dispute,” one said to God, “what have ye to interfere?” In other words: What business is it of yours? The Torah had already been given to Moses at Mount Sinai, he explained, and thereafter “we pay no attention to a Heavenly Voice.” The text and its human readers trumped God. God’s response? He laughed, saying, “My sons have defeated Me, My sons have defeated Me.” Well played, Babylonian sages, well played.

…

Jews, they claim, have a unique collective identity that is not religious, not biological, but rather textual. From the very beginning, they argue, the Jewish people shared the Hebrew Bible and its laws orally from one generation to the next. But after the destruction of the Second Temple in the year 70 and the subsequent exile of the Jews into the Diaspora, the Jewish people existed only insofar as their texts existed. They possessed no geographical or other unifying identity outside the Torah, rabbinical texts, poetry, and women’s and children’s books. For Jews, literacy and community have gone hand in hand, from ancient and medieval times to today.

…

Given the title and the book’s focus on survival, its scope is surprisingly narrow. Anyone expecting a more expansive historical or literary survey of the relationship of Jews to words, from King David to Larry David, will be disappointed. European and American luminaries like Spinoza, Sholem Aleichem and Philip Roth are discussed, but the focus skews toward the Hebrew Bible, with a leap to modern Hebrew writers (including, on occasion, Amos Oz quoting himself). What of the huge legacy of Yiddish literature? Where is the footprint of American Jewish culture? The book presumes that exile has necessitated and nurtured a text-based tradition, yet it breezes past large chunks of Diaspora history and culture.

…

Israelis and Hebrew would have been a more apt title: the open and porous notion of Jewish identity and culture that the authors champion ultimately appears more parochial than they intended.

“This book is not about current affairs,” they write. “We are not bringing our take on Jewish history and continuity to bear on the present Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But we cannot ignore the political meaning of our claim to a Jewish textline, and our belief in the superiority of books over material remains.” However, when you make an eloquent case (as the authors do) that “ours is not a bloodline but a textline,” what does it mean if you live in a state whose citizenship laws are in fact based on bloodline? For all the luftmensch talk about a heritage that is “paved with words,” that rhetoric reveals itself to be a tactic in a struggle over actual physical space: between secular and Orthodox Jews within the state of Israel, and between Israelis and Palestinians over the land itself. Those struggles may be why the authors fail to address a question their book fairly demands: If the relationship of Jews to books is largely a product of the Diaspora, what happens when that exile comes to an end in the form of a Jewish state? In a book that extols the virtues of a textual tradition rooted in the asking of questions, this is one that should not be overlooked.

March 3, 2013

Israel v. Palestine, Plessy v. Ferguson

Haaretz (3/13/13):

Starting on Monday, certain buses running from the West Bank into central Israel will have separate lines for Jews and Arabs.

The Afikim bus company will begin operating Palestinian-only bus lines from the checkpoints to Gush Dan to prevent Palestinians from boarding buses with Jewish passengers. Palestinians are not allowed to enter settlements, and instead board buses from several bus stops on the Trans-Samaria highway.

Last November, Haaretz reported that the Transportation Ministry was looking into such a plan due to pressure from the late mayor of Ariel, Ron Nahman, and the head of the Karnei Shomron Local Council. They said residents had complained that Palestinians on their buses were a security risk.

The buses will begin operating Monday morning at the Eyal crossing to take the Palestinians to work in Israel. Transportation Ministry officials are not officially calling them segregated buses, but rather bus lines intended to relieve the distress of the Palestinian workers.

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896):

Laws permitting, and even requiring, their separation in places where they are liable to be brought into contact do not necessarily imply the inferiority of either race to the other, and have been generally, if not universally, recognized as within the competency of the state legislatures in the exercise of their police power.

…

…Every exercise of the police power must be reasonable, and extend only to such laws as are enacted in good faith for the promotion for the public good, and not for the annoyance or oppression of a particular class.

…

In determining the question of reasonableness, it is at liberty to act with reference to the established usages, customs, and traditions of the people, and with a view to the promotion of their comfort and the preservation of the public peace and good order. Gauged by this standard, we cannot say that a law which authorizes or even requires the separation of the two races in public conveyances is unreasonable…

…

We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff’s argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.

March 1, 2013

Lucille Dickess (1934-2013): American Radical

On February 21, Lucille Dickess died at the age of 79. Lucille worked as the registrar of the geology department at Yale University and served as the president of the clerical and technical workers union, Local 34. (This photo of Lucille was taken by Virginia Blaisdell.)

On February 21, Lucille Dickess died at the age of 79. Lucille worked as the registrar of the geology department at Yale University and served as the president of the clerical and technical workers union, Local 34. (This photo of Lucille was taken by Virginia Blaisdell.)

I can still remember the first time I saw and heard Lucille speak. It was at a rally on Beinecke Plaza, I think in the spring of 1991. She had white hair, looked like a suburban grandmother, and breathed fire. I had always thought of union workers as burly white guys. I never thought that again. She was, to me, what the labor movement at its best is about: transcending easy and lazy stereotypes of who we are, forging the most unexpected solidarity among men and women who are so different from each other in so many way. And she was very funny. I’ll miss her.

The New Haven Independent (h/t Zach Schwartz-Weinstein) has published some excerpts from an interview with Lucille. If you want a sense of how radicalizing an experience joining a union can be, you should read all of it. (And keep in mind that Lucille had been a scab before she joined the union.) Here are some highlights:

I had totally rejected the UAW because they told us they were going to do it, and not to worry about anything. “Sign the card, we’ll take care of everything.” When HERE [Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees union] came in, it was different. With HERE it came down to, “This will be your union, and you’ll have to make of it what you will.” Now, none of us knew anything about unions, really, so this was an amazing step we took, just to say, “The worst thing here are job descriptions and salaries.” But how in the world do you fix that? Where do you begin to fix that?

Well, the HERE organizers said, “You have to talk to everybody,” and that made sense to me.

I loved the structure. Loved it. I just loved it. I’m responsible for sixty-one people. I know who’s got trouble at home, who’s got trouble at work, who’s being threatened. This was so satisfying, mathematically, and physically, and emotionally, and practically. A lot of people were very afraid to get involved. I was hearing from people, “I’m afraid I’ll get fired.” “I don’t know anything about unions.” “You have to pay union dues.” “I’ll get in trouble.” “Nobody else here is interested, it’s only me.” There were probably as many reasons as there were people, when you got right down to it.

…

Right after I became president of Local 34, I was invited to a Local 35 membership meeting so people would get to meet me. I told them that I had scabbed. Because I’d been asked to work in dining halls when one of the strikes was on. I was just divorced, there was no sign of any child support coming in, and also my husband had signed bankruptcy, so everybody in the world was coming after me for all of these bills he hadn’t paid, and I still had one child at home. So I didn’t give a thought to the fact that people were out on strike – all I thought was, I can make some extra money. And I went into dining halls and I scabbed, I told them.

I just wanted them to know: don’t ever write anybody off, because I changed. I came all that way from non-thinking, not knowing, and I learned, and so here’s where I am now. So a lot of people were not too thrilled to hear me say this, but afterwards Tom (Gaudioso) said to me, “I’ve got to give it to you: you had a lot of balls to say that to them.” And I said, “Well, I wanted them to understand somehow that when we were crossing their lines, we weren’t thinking, we weren’t conscious of what was going on, and shame on us that we didn’t find out about it. But once we did, we learned: here’s how you do.”

35 was always a model to me. They really were. To accept us, who had crossed their lines for so many years – to accept us as their partners, to work together and never mind our differences, to put aside all that resentment and hurt and join together so closely that we were really brothers and sisters.

…

Years later, I bumped into (a woman from the picket line) and she said, “You know, that was the most wonderful thing I ever did in my entire life.” And I would bet, if you went around and asked everybody who was out on the line in that strike, you’d have 95% of them say the same thing. Absolutely. Because you were taking the power yourself.

Update (March 2, 7:30 pm)

David Sanders, with whom I organized at Yale and who is now a union organizer up in Canada, posted a reminiscence of Lucille on my FB page. I wanted to share part of it here:

I have two memories in particular of Lucille. One was her retirement speech where she said: “First I was a daughter, then a wife, then a mother but I didn’t become a woman until I became a sister in the union.”

February 27, 2013

What do Glenn Greenwald, Alan Dershowitz, and the Israeli UN Ambassador have in common?

Glenn Greenwald will be delivering the Brooklyn College political science department’s 39th annual Samuel J. Konefsky Memorial Lecture this year. The topic of the lecture: “Civil Liberties and Endless War in the Age of Obama.” The lecture will be held on Monday, March 4, at 1 pm. In the Gold Room (6th Floor) of SUBO, which is the student center building, located at Campus Road and 27th Street. The lecture is open to the public.

Like Alan Dershowitz, a previous Konefsky Lecturer, Greenwald will be speaking alone. Like the Israeli Ambassador to the UN, Greenwald will balance himself.

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 155 followers