Corey Robin's Blog, page 99

June 25, 2013

The Hayek-Pinochet Connection: A Second Reply to My Critics

In my last post, I responded to three objections to my article “Nietzsche’s Marginal Children.” In this post I respond to a fourth regarding the connection between Friedrich von Hayek and Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet.

Though my comments on that connection took up a mere three sentences in my article, they’ve consumed an extraordinary amount of bandwidth among my libertarian critics. At Bleeding Hearts Libertarians, Kevin Vallier repeatedly accuses me of “smearing” Hayek with the Pinochet connection:

When Hayek was eighty he said that Pinochet was an improvement on Allende. This was a serious mistake in judgment, but it is not significant for Hayek’s body of work in any way. Why would it be?

Libertarian journalist Julian Sanchez says, “I don’t think anyone denies that was a grotesque mistake but…what? Hayek isn’t Jesus? Unsure why we’re supposed to care.” And again: “I mean, maybe Hayek was a shit human being. Let’s suppose. Still. Why do I care?”

While Sanchez and Vallier concede that Hayek was wrong on Pinochet, much of the libertarian commentariat at Bleeding Hearts do not. Here’s a representative remark:

I am now going to utter what some have been thinking: perhaps Hayek was right. 190 units of evil is better than 191 units of evil (if there were any such thing)….Let me affirm it loud and clear: Pinochet was better than Allende.

The claims of my libertarian critics boil down to these: The Pinochet connection is little more than Hayek saying Pinochet was better than Allende. That was a bad call (though some of these professors of liberty aren’t sure), but Hayek was 80 when he made it. His political judgment was clouded not by ideology but age. (Last summer, Vallier even broached the issue, in this context, of Hayek’s “important mental decline.”) So who cares? To raise the Pinochet connection is a smear, a smear so low I should be banned from Crooked Timber.

Let’s take these one at a time.

Hayek only said that Pinochet was better than Allende

This is absurd. The Hayek-Pinochet file is so extensive that I could only give it the barest mention in my Nation piece. Here’s the brief version of the story; all supporting evidence can be found in these five posts and the links therein.

Hayek first visited Pinochet’s Chile in 1977, when he was 78. Amnesty International had already provided him with ample evidence of Pinochet’s crimes—much to his annoyance—but he went anyway. He met with Pinochet and other government officials, who he described as “educated, reasonable, and insightful men.” According to the Chilean newspaper El Mercurio, Hayek

told reporters that he talked to Pinochet about the issue of limited democracy and representative government….He said that in his writings he showed that unlimited democracy does not work because it creates forces that in the end destroy democracy. He said that the head of state listened carefully and that he had asked him to provide him with the documents he had written on this issue.

Hayek complied with the dictator’s request. He had his secretary send a draft of what eventually became chapter 17—“A Model Constitution”—of the third volume of Law, Legislation and Liberty. That chapter includes a section on “Emergency Powers,” which defends temporary dictatorships when “the long-run preservation” of a free society is threatened. “Long run” is an elastic phrase, and by free society Hayek doesn’t mean liberal democracy. He has something more particular and peculiar in mind: “that the coercive powers of government are restricted to the enforcement of universal rules of just conduct, and cannot be used for the achievement of particular purposes.” That last phrase is doing a lot of the work here: Hayek believed, for example, that the effort to secure a specific distribution of wealth constituted the pursuit of a particular purpose. So the threats to a free society might not simply come from international or civil war. Nor must they be imminent. As other parts of the text make clear, those threats could just as likely come from creeping social democracy at home. If the visions of Gunnar Myrdal and John Kenneth Galbraith were realized, Hayek writes, it would produce “a wholly rigid economic structure which…only the force of some dictatorial power could break.”

Hayek came away from Chile convinced that an international propaganda campaign had been unfairly waged against the Pinochet regime (and made explicit comparison to the campaign being waged against South Africa’s apartheid regime). He set about to counter that campaign.

He immediately wrote a report lambasting human rights critics of the regime and sought to have it published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. The editor of this market-friendly newspaper refused, fearing that it would brand Hayek as “a second Chile-Strauss.” (Franz Josef Strauss was a right-wing German politician who had visited Chile in 1977 and met with Pinochet. His views were roundly repudiated by both the Social Democrats and the Christian Democrats in Germany.) Hayek was incensed. He broke off all relations with the paper, explaining that if Strauss had indeed been “attacked for his support for Chile he deserves to be congratulated for his courage.”

The following year, Hayek wrote to the London Times, “I have not been able to find a single person even in much maligned Chile who did not agree that personal freedom was much greater under Pinochet than it had been under Allende.” (This is the statement that Vallier believes exhausts the contents of Hayek’s Pinochet file.)

In 1981, Hayek returned to Chile. The Pinochet regime had recently adopted a new constitution, which it named after The Constitution of Liberty. During this visit, El Mercurio interviewed him again and asked him what “opinion, in your view, should we have of dictatorships?” Demonstrating that he was fully aware of the dictatorial nature of the Pinochet regime, Hayek replied:

As long-term institutions, I am totally against dictatorships. But a dictatorship may be a necessary system for a transitional period. At times it is necessary for a country to have, for a time, some form or other of dictatorial power. As you will understand, it is possible for a dictator to govern in a liberal way. And it is also possible for a democracy to govern with a total lack of liberalism. Personally, I prefer a liberal dictator to democratic government lacking in liberalism. My personal impression…is that in Chile…we will witness a transition from a dictatorial government to a liberal government….during this transition it may be necessary to maintain certain dictatorial powers.

(The transition Hayek imagines here would not occur for another seven to eight years, over and against the wishes of the “liberal dictator” Pinochet.)

In a second interview with El Mercurio, Hayek again praised temporary dictatorships “as a means of establishing a stable democracy and liberty, clean of impurities” and defended the “Chilean miracle” for having broken, among other things, “trade union privileges of any kind.” In a separate interview not long after, he said the only totalitarian government in Latin America he could think of was “Chile under Allende.”

But Hayek’s greatest contribution to the Pinochet regime may well have been his effort to organize the 1981 convention of the Mont Pelerin Society that was held in Viña del Mar, the Chilean city where the coup against Allende had been planned. Hayek was in on the convention plan from the beginning. As early as 1978, he was working with Carlos Cáceres—a member of Pinochet’s Council of State and soon to be a high-ranking minister in the regime—on the schedule and financing of the conference. It turned out to be a spectacular propaganda coup for the regime. The backdrop of the conference, explained its official rapporteur, was the bad rap “the often maligned land of Chile” was getting in the international media. The conference made a point of providing its participants with an opportunity “for becoming better acquainted with the land which has had such consistently bad and misrepresenting press coverage.” Two hundred and thirty men and women—including James Buchanan, Gordon Tullock, and Milton and Rose Friedman—from 23 countries attended. Like pilgrims to the Soviet Union, they were treated to lavish displays of the wonders of their host country and were happily trotted out for interviews with the media.

After the convention, Hayek milked it for all that it was worth. When the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, for example, published a cartoon comparing Pinochet’s Chile to Jaruzelski’s Poland, he fired off an angry letter to the editor:

I cannot help but protest in the strongest possible terms against the cartoon on page 3 of your publication of the 30th of December equating the present governments of Poland and Chile. It can only be explained by complete ignorance of the facts or by the systematically promoted socialist calumnies of the present situation in Chile, which I had not expected the F.A.Z. to fall for. I believe that all the participants in the Mont Pelerin Society conference held a few weeks ago in Chile would agree with me that you owe the Chilean government a humble apology for such twisting of the facts. Any Pole lucky enough to escape to Chile could consider himself fortunate.

These were just some of Hayek’s actions and statements on behalf of Pinochet’s Chile over a five-year period. As the Hayek archives reveal, the regime was more than grateful for his efforts and repeatedly conveyed their thanks to him. As Cáceres wrote Hayek: “The press has given wide coverage to your opinions and I feel no doubt that your thoughts will be a clarifying stimmulous [sic] in the achievements of our purposes as a free country.”

This old man

Let’s assume, for the sake of the argument, that the whole of Hayek’s contribution to the regime can be found in that letter to the Times, where he favorably compares Pinochet to Allende. That was in 1978, a mere two years after the publication of volume 2 of Law, Legislation and Liberty and a full year before the publication of volume 3. These books are generally recognized to be among Hayek’s greatest contributions to political theory. The notion that Hayek was sufficiently compos mentis to write these classics but not to understand what he was saying about Pinochet is risible.

The Pinochet connection has nothing to do with Hayek’s ideas

As Andrew Farrant, Edward McPhail, and Sebastian Berger document in their exhaustive treatment of the Pinochet connection, Hayek had a long-standing interest, pre-dating his engagement with Pinochet, in the idea of temporary dictators and strongmen. It is a running thread throughout his work, and more than a decade before his dance with Pinochet, Hayek took a turn with the Portuguese dictator Antonio Salazar.

Even in Constitution of Liberty, which makes a powerful case for the evolutionary nature of rule formation, we get a glimpse of a Schmittian-type legislator stepping forth “to create conditions in which an orderly arrangement [of rules] can establish and ever renew itself.” That, Hayek says, is “the task of the lawgiver.” (Hayek sent the text to Salazar, perhaps with that very passage in mind.)

Again, Hayek did not imagine the dictator as simply a response to foreign attack or domestic insurrection; he was the antidote to the discretionary free-fall of a socialist state run amok. When a “government is in a situation of rupture,” Hayek told his Mercurio interviewer in 1981, “and there are no recognized rules, rules have to be created.”

But it is precisely on this notion of the dictator as a creator of rules that Hayek’s theory falters, for nothing in his notion of evolutionary rule formation seems to allow—or, more precisely, to account—for it. Though Hayek frequently speaks of this dictator, the strongman seems to be, almost literally, a miracle: an appearance from nowhere, with no background or context to explain it. Not unlike Schmitt’s notion of the decision or the exception—or, as Henry Farrell points out, the notion of innovation in standard economic models of equilibrium that Hayek, Schumpeter, and the other Austrians so chafed at.

One might say, I suppose, that Hayek failed to develop or account for this idea because it meant so little to him. But Farrant et al show that’s not the case. The more likely explanation is that it meant a great deal to him but that he wanted it to remain a miracle out of the whirlwind, or simply didn’t know how to reconcile it with his ideas about evolutionary rule formation. In either case, it was a circle he couldn’t square.

Hayek’s failure to grapple with what he was doing with dictators theoretical and actual is symptomatic of a larger problem: not his personal flaws—as libertarian Jesse Walker points out, Hayek was not the only libertarian to embrace Pinochet; Austrian economist and libertarian George Reisman called Pinochet “one of the most extraordinary dictators in history, a dictator who stood for major limits on the power of the state”—but the vexed relationship between capitalism and coercion, a relationship, as we’ve seen, libertarians have a difficult time coming to terms with.

Whether we call it primitive accumulation or the great transformation, we know that the creation of markets often require or are accompanied by a high degree of coercion. This is especially true of markets in labor. Men and women are not born wage laborers ready to contract with capital. Nor do they simply evolve into these positions over time. Wage laborers are often made—and remade—through violence, coercion, and force. Like the labor wars of the Gilded Age or the enclosure riots, Pinochet’s Chile was about the forcible creation, at lightning speed, of new markets in land and labor.

Hayek’s failure to fully come to terms with this reality—his idea of a good “liberal dictator” shows that he was more than aware of it; the fact that so little in his work on rule formation gives warrant to such an idea demonstrates the theoretical impasse in which he found himself—is why his engagement with Pinochet is so important. Not because it shows him to be a bad person but because it reveals the “steel frame,” as Schumpeter called it, of the market order, the unacknowledged relationship between operatic violence and doux commerce.

In his excellent post, Walker suggests that Hayek didn’t have to respond to Pinochet as he did. If that’s the case, the burden is on my critics to explain why he did—without resorting to “he was an old man” foolishness. But I wonder if Walker is right: not about markets but about the man. And here I circle back to the question of Hayek the theorist.

Given everything we know about Hayek—his horror of creeping socialism, his sense of the civilizational challenge it posed; his belief that great men impose their will upon society (“The conservative peasant, as much as anybody else, owes his way of life to a different type of person, to men who were innovators in their time and who by their innovations forced a new manner of living on people belonging to an earlier state of culture”); his notion of elite legislators (“If the majority were asked their opinion of all the changes involved in progress, they would probably want to prevent many of its necessary conditions and consequences and thus ultimately stop progress itself. I have yet to learn of an instance when the deliberate vote of the majority (as distinguished from the decision of some governing elite) has decided on such sacrifices in the interest of a better future”); and his sense of political theory and politics as an epic confrontation between the real and the yet-to-be-realized—perhaps the Pinochet question needs to be reframed. The issue is not “How could he have done what he did?” but “How could he not?”

So what? Who cares? Stop the smearing!

My response to the above claims should answer the “So what? Who cares?” question and set to rest the notion that I was smearing an old man. If anything I let him off easy.

June 24, 2013

Nietzsche, Hayek, and the Austrians: A Reply to My Critics

My article “Nietzsche’s Marginal Children” has provoked much criticism, some of it quite hostile. (Here’s a complete list of the responses I’ve received.)

The criticism focuses on four issues: the connection between Nietzsche and Austrian economists such as Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek; the question of Hayek’s elitism; the relationship between economic and non-economic value; and the relationship between Hayek and Pinochet.

I address three of these criticisms here—a separate post on Hayek and Pinochet will follow—but first let me restate the argument of the piece and explain why I wrote it.

“Nietzsche’s Marginal Children” juxtaposes Nietzsche’s critique of the idea of objective value with the turn to subjective theories of value in economics, first among the early marginalists of the 1870s and later, and more important for my purposes, in the Austrian School coming out of the work of Carl Menger. Describing the relationship between Nietzsche’s philosophy and Austrian economics as one of elective affinity, I draw out deep structural similarities between two ways of thinking (about value, elitism, and the role of struggle and sacrifice in the creation or definition of value) that are seldom put in dialogue with each other. The reason I bring together Nietzsche and the Austrians (as opposed to other figures) is that a similar project animates their thinking: the effort to repulse the socialist challenge of the late 19th and 20th centuries and, behind socialism, the elevation of labor and the laborer as the centerpiece of modern civilization. The idea that the worker drives not only the economy but culture and society as well–and the concomitant notion that an alternative formulation of value might help repel that idea and the politics it inspires—is the polemical context that unites these figures.

Rather than treat the Austrians as the inheritors of classical liberalism, I see in this theory an attempt to recreate what Nietzsche called grosse Politick in the economy. Most treatments of the Austrians fail to capture their agonistic romance of the market, a romance that makes capitalism exciting rather than merely efficient. Far from departing from the canons of conservatism, then, Austrian economics is a classic form of counterrevolution, a la Burke. It seeks to defeat a challenge from below—in this case, the ongoing threat from the worker’s world, whether that world be found in a grain of sand (a trade union, say) or in the surrounding sea of international socialism—by transforming and reinvigorating the old regime. “If we want things to stay as they are,” as the classic formulation in The Leopard puts it, “things will have to change.”

I wrote the piece mainly in pursuit of an idea coming out of my encounter with Carl Schorske’s Fin-de-Siècle Vienna. Situating the rise of modernism in the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, this classic study hears the drumbeat of Viennese politics—a flailing ancien régime, a bourgeoisie struggling to extract a liberal order from “the feudals,” and a vicious street fight of right and left— in Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, Klimt’s Athena portraits, and other touchstones of high culture.

Schorske’s book spawned an entire literature devoted to the Viennese origins of logical positivism, psychoanalysis, atonal music, and more. Yet there has always been a conspicuous absence in that literature: the Austrian School of economics. Even though the Austrian School was forged in the same Schorskean crucible of a regnant aristocracy, weak liberalism, and anti-socialism, even though the Austrian economists offer an appreciation of the subjective, non-rational, and unconscious elements of life rivaling that of Freud, Klimt, and Kokoschka, the Austrians make no appearance in Schorskean histories of Vienna and Schorske’s Vienna makes no appearance in studies of the Austrians. It’s as if there is a tacit vow of silence among two sets of scholars: historians and leftists who do not want to concede any cultural status or philosophical depth to (in their view) vulgarians of the market like Mises and Hayek, and libertarians and economists who do not want to see their inspirations tainted by the politics of Vienna.

The text that comes closest to apprehending the swirling presence of Vienna in Austrian economics is John Gray’s Hayek on Liberty. Not only does Gray emphasize the subterranean quasi-rational currents of Viennese subjectivism in Hayek’s theories but he also captures the distinctively counterrevolutionary—as I have explained the term—character of Hayek’s enterprise, which entails “a radical revision both of current and ancient morality.”

In pursuing the re-evaluation of values that are necessary to the stability of the market order…Hayek’s doctrine issues in judgments critical of large segments of moral practice. Hayek’s example suggests that radicalism and conservatism in intellectual and moral life may not be in conflict at all….It has the paradoxical result that a contemporary conservative who values private property and individual liberty cannot avoid being an intellectual and moral radical.

Gray’s book doesn’t get too much play anymore, but at the time of its publication in 1984 one reader claimed that it was “the first survey of [Hayek’s] work which not only fully understands but is able to carry on [his] ideas beyond the point at which [he] left off.”

That reader was Friedrich von Hayek.

What is the connection between Nietzsche and the Austrians?

The most common criticism of my piece that I’ve received is that my linking of Nietzsche and the Austrians fails because many other philosophers and economists held similarly subjectivist views of value. Unless I want to make the case that Nietzsche influenced the Austrians, which I don’t, I’m either saying something trivial (i.e., like many thinkers across the centuries, Nietzsche and the Austrians held a particular view of value) or trying to smuggle lurid contraband (freedom-loving Austrians = fascist-leaning Nietzsche) inside my suitcase.

My critics are certainly correct that many other writers held subjectivist theories of value and that many of them were socialists and leftists. What’s puzzling is that I make that very point in my article, repeatedly in fact. So why do these critics believe it is so fatal? Because they ignore the argument I do make in favor of an argument I don’t make.

Notice how these critics set up my argument. At The American Conservative, Samuel Goldman writes:

According to Robin, both Nietzsche and the Austrians saw value as a subjective commitment under conditions of constraint rather than an objective contribution by labor. For this reason, they endorsed agonistic social relations in which individuals struggle to express and impose valuations to the limits of their differential strength, while rejecting egalitarian arrangements that attempt to give producers a fair share of the value they have generated.

Bleeding Heart Libertarians’s Kevin Vallier writes:

Robin roughly claims that the move to the subjective theory of economic value in economics was a move towards a form of objective value nihilism. Objective value nihilism in turn allows Austrian economists in particular to argue that markets are an expression of morality because markets are expressions of subjective value.

In both formulations, value subjectivism (I don’t know where Vallier gets value nihilism from) is doing the work of leading Nietzsche and the Austrians to their dark end, whether in politics or the market. That makes an easy target for both critics because it allows them to point to other subjectivists who did not take the path of anti-socialism or elitism and thereby to dismiss the Nietzsche Hayek connection. (“If even Mises’s chief [ideological] opponent shared his theory of value,” claims Vallier, “how can there be an interesting, illuminating connection between Nietzsche and the Austrians?”)

But that’s not how elective affinities work. It’s not that one argument or tradition logically entails another—marching its proponent down the road, forcing him to take a right at the intersection—or that the two arguments are found together and only together. There clearly is an elective affinity between liberalism and contractarianism, for example, even though there are liberals who are not contractarians (Montesquieu, Constant, Tocqueville, Hegel, and Dewey) and contractarians who are not liberals (Hobbes).

The point of an elective affinity is that there’s something in the two traditions—a deep structure of thought common to both that might not be immediately visible in each or arguments peculiar to each that are nevertheless congenial to both—that draws their proponents to each other. Or that explains why proponents of the one, once they have abandoned it, may subsequently be drawn to the other. Or why a culture—or political movement—may comfortably birth or house both at the same time. In the case of a political movement, where power and interests and ideas mix and mingle in ways that don’t always logically fit or follow, elective affinities can be especially potent.

For all their peculiar insistence on the need for me to demonstrate uniqueness—to establish a connection between Nietzsche and the Austrians, Vallier says, I must show they “were unique in sharing these views” about value, a stipulation so eccentric it would render unintelligible such classics of intellectual history as Richard Hofstadter on Calhoun (“The Marx of the Master Class”), Louis Menand on pragmatism and the Civil War, or Schorske on Vienna and modernism—my critics overlook what is in fact unique to Nietzsche and the Austrians as well as some of their followers: not their subjectivism but the fact that they saw in their subjectivism a comprehensive vision of politics, morals, and culture, a renovation of the human estate so complete as to rival that of the left. More than a simple theory of economics or metaethics, subjectivism offered these writers a glimpse of counterrevolutionary eternity,

Like Nietzsche, the Austrians were political theorists, men who sought to set the world ablaze. They understood that the battle against socialism would not be won by a dry recitation of economic facts or a dull roster of normative arguments. A truly political theory had to seize our sense and our sensibility. “I do not think the cause of liberty will prevail unless our emotions are aroused,” Hayek announces in the opening pages of The Constitution of Liberty. “If politics is the art of the possible,” he adds, “political philosophy is the art of making politically possible the seemingly impossible.”

That is why this particular objection from Goldman is so off base.

Robin generally ignores the technical mathematical background of the marginal revolution, which he presents primarily as debate in moral philosophy. That decision obscures the most important cause of the transformation of economic thought in the 19th century: the demand that economics become a science on the model of physics.

Goldman is wrong, of course, about Menger, one of the three founders of marginalism who was notoriously hostile to mathematical and scientific models of economics. He’s also wrong about Menger’s successors, who are the main topic of my article: Mises was contemptuous of “mathematical modes of representation” and the “drawing of such curves” as well as of the effort to model economics on the example of physics or chemistry. In one of his seminal articles, Hayek states that the problem of economics has “been obscured rather than illuminated by many of the recent refinements of economic theory, particularly by many of the uses made of mathematics.” That “misconception,” he goes onto say, “is due to an erroneous transfer to social phenomena of the habits of thought we have developed in dealing with the phenomena of nature.”

But more important, Goldman misses the entire point of the Austrian enterprise: to transcend the narrow confines of economics (as well as the natural sciences) and to fashion a genuinely political theory of markets and morals. In Hayek’s words, “I have come to feel more and more that the answers to many of the pressing social questions of our time are to be found ultimately in the recognition of principles that lie outside the scope of technical economics or of any other single discipline.” That was the music of these marginalists’ morals.

What distinguishes the Austrians and Nietzsche, then, from other subjective theorists (indeed, from practically all the names that have been raised in response to me: Oskar Lange, Karl Marx, Carlyle, Dostoevsky, Burckhardt, Tocqueville, Mill, Hobbes) is: a) the polemical target and context of their subjectivism—the threat of socialism and the labor question more generally; b) the connection they draw and that can be drawn between their subjectivism and their anti-socialism and elitism (a connection, it bears repeating, that is neither necessary nor inherent but contingent and peculiar to this moment and to the subsequent development of the right); and c) the cultural scope and political ambition of their subjectivism.

Übermenschen/Untermenschen

A second criticism I’ve received is that I offer virtually no evidence to support my claim that Nietzsche and the Austrians share a belief in great men as the creators and legislators of new forms of value, not just economic goods but also political, moral and cultural norms. Here is Vallier (if I cite him more than my other critics it is simply because his post has served as the touchstone for so many of the rest):

But suppose we scrutinize one of Robin’s most well-developed and specific claims, namely that there is an interesting and illuminating connection between Nietzsche’s and Hayek’s view about the importance of great men setting out new forms of valuation for social development. Even here the argument fails. The only passages from Hayek that can even be construed out of context to support this argument is Hayek’s claim in The Constitution of Liberty that synchronic (simultaneous) inequalities of wealth can work to the benefit of the least-advantaged over time because the luxury consumption of the rich paves the way for manufacturers to create cheaper versions of the same goods and market them to the masses.

This is ludicrous.

Immediately after he makes this narrow point about luxury goods, Hayek insists that the trickle-down effects of great wealth and inequality far outstrip the simple creation of mass consumption items.

The important point is not merely that we gradually learn to make cheaply on a large scale what we already know how to make expensively in small quantities but that only from an advanced position does the next range of desires and possibilities become visible, so that the selection of new goals and the effort toward their achievement will begin long before the majority can strive for them. If what they will want after their present goals are realized is soon to be made available, it is necessary that the developments that will bear fruit for the masses in twenty or fifty years’ time should be guided by the views of people who are already in the position of enjoying them.

The role of the wealthy it is to “guide” the development of the “range of desires,” the “selection of new goals,” of “the masses.” These elite effects are not merely economic but also cultural and moral. Far from saying this only once, Hayek says it a great many times.

However important the independent owner of property may be for the economic order of a free society, his importance is perhaps even greater in the fields of thought and opinion, of tastes and beliefs.

…

The importance of the private owner of substantial property, however, does not rest simply on the fact that his existence is an essential condition for the preservation of the structure of competitive enterprise. The man of independent means is an even more important figure in a free society when he is not occupied with using his capital in the pursuit of material gain but uses it in the service of aims which bring no material return.

…

What little leadership can be expected from the majority is shown by their inadequate support of the arts wherever they have replaced the wealthy patron. And this is even more true of those philanthropic or idealistic movements by which the moral values of the majority are changed.

…

The leadership of individuals or groups who can back their beliefs financially is particularly essential in the field of cultural amenities, in the fine arts, in education and research, in the preservation of natural beauty and historic treasures, and, above all, in the propagation of new ideas in politics, morals, and religion.

…

It is only natural that the development of the art of living and of the non-materialistic values should have profited most from the activities of those who had no material worries.

Beyond being wrong, this particular criticism fails because of the implicit separation it draws between economic and cultural development, moral and material progress, patterns of consumption and a broader way of life. That way of thinking is utterly foreign to Hayek.

Here again some acquaintance with the Viennese context, particularly the aristocratic context, might be useful. In the course of defending familial inheritance, for example, Hayek repeatedly makes the point that the transmission of elite values, tastes, and beliefs is predicated on the transmission of wealth. The “external forms of life” condition and support the inner forms of life.

Many people who agree that the family is desirable as an instrument for the transmission of morals, tastes, and knowledge still question the desirability of the transmission of material property. Yet there can be little doubt that, in order that the former may be possible, some continuity of standards, of the external forms of life, is essential, and that this will be achieved only if it is possible to transmit not only the immaterial but also material advantages.

…

The family’s function of passing on standards and traditions is closely tied up with the possibility of transmitting material goods.

Elsewhere, after claiming that “the freedom that will be used by only one man in a million may be more important to society and more beneficial to the majority than any freedom that we all use”—a statement taken by my critics to mean that any random individual may make economic contributions to the society as a whole—Hayek favorably cites this statement of support from a nineteenth-century philosopher:

The plea for liberty is not sufficiently met by insisting…upon the absurdity of supposing that the propertyless labourer under the ordinary capitalistic regime enjoys any liberty of which Socialism would deprive him. For it may be of extreme importance that some should enjoy liberty—that it should be possible for some few men to be able to dispose of their time in their own way—although such liberty may be neither possible nor desirable for the great majority. That culture requires a considerable differentiation in social conditions is also a principle of unquestionable importance.

There’s no wisdom of crowds here. Not only is Hayek speaking of the wealthy, but he is also claiming that their wealth, and the inequality it generates, will have cultural benefits for the masses.

But more generally, if the claim of Austrian elitism is as outlandish as my critics seem to believe, would Mises have praised Ayn Rand—whose economic Nietzscheanism (though not subjectivism) is not in doubt—thus?

You have the courage to tell the masses what no politician told them: you are inferior and all the improvements in your conditions which you simply take for granted you owe to the effort of men who are better than you.

Or characterized the popularity and appeal of Marxism thus?

The incomparable success of Marxism is due to the prospect it offers of fulfilling those dream-aspirations and dreams of vengeance which have been so deeply embedded in the human soul from time immemorial. It promises a Paradise on earth, a Land of Heart’s Desire full of happiness and enjoyment, and—sweeter still to the losers in life’s game—humiliation of all who are stronger and better than the multitude.

Non-elitists tend not to speak this way.

Value(s)

A third criticism of my piece is that I make a muddle of the question of value by failing to distinguish between economic and moral value, use-value and exchange-value—“between any particular form of value and ‘value’ itself,” as Vallier puts it. I also misfire when I claim that Mises and Hayek “made the market the very expression of morality.” Neither man, Vallier says, “makes market relations ‘the very expression’ of morality.”

There’s no question that my piece mixes different notions of value, blurring distinctions that philosophers like to keep separate. But far from haplessly misconstruing one mode of value for another, I intentionally pressed these definitions and usages together. And for a simple reason: that’s what the Austrians did. This was a critical part of their project, which I was trying to capture.

Let’s recall the political and intellectual context in—and against—which the Austrians were writing. For nearly a half-century, leftists had been arguing that economic questions should be subordinate to moral questions. More technocratic types argued that the government could solve the economic problem in an apolitical fashion, freeing men and women to pursue their visions of the good life with the resources they needed. What made these arguments possible was the notion that economics and morals occupied distinct spheres.

Hayek understood this threat all too well. (Some libertarians still do.) Economic planners, he said, believe their actions “will apply ‘only’ to economic matters.”

Such assurances are usually accompanied by the suggestion that, by giving up freedom in what are, or ought to be, the less important aspects of our lives, we shall obtain greater freedom in the pursuit of higher values.

It was as if, in the minds of the planners, “economic activities really concerned only the inferior or even more sordid sides of life.” But that vision, Hayek insisted, “is altogether unwarranted. It is largely a consequence of the erroneous belief that there are purely economic ends separate from the other ends of life.”

Mises was equally clear on the matter:

Unless Ethics and “Economy” are regarded as two systems of objectivization which have nothing to do with each other, then ethical and economic valuation and judgment cannot appear as mutually independent factors….The conception of absolute ethical values, which might be opposed to economic values, cannot therefore be maintained.

Instead of separating economic and moral values, the Austrians sought to join and mix them. They further argued that moral values are best revealed, or most likely to be revealed, in the marketplace because it is in the marketplace that we are forced to give something up for them. Deep inside their conception of moral action was a notion of sacrifice—“Moral behavior is the name we give to the temporary sacrifices made in the interests of social co-operation,” declared Mises; “to behave morally, means to sacrifice the less important to the more important”—which was most tangibly demonstrated and viscerally experienced in acts of market exchange.

According to Hayek, morals “can exist only in the sphere in which the individual…is called upon voluntarily to sacrifice personal advantage to the observance of a moral rule.” One must prove “one’s conviction by sacrificing one’s desires to what one thinks right.” In the economy we are constantly forced to give up something of ourselves, something material, in order to honor our notions of what is right or good. What Hayek calls the “economic problem”—the fact that “all our ends compete for the same means,” which are limited and scarce—provides the best, indeed the only, habitat for that kind of moral action.

Contra Vallier—who claims that Hayek believes that “morality can be expressed in all sorts of ways” and “can be promoted outside of the market”—Hayek states quite clearly that

freedom to order our own conduct in the sphere where material circumstances force a choice upon us…is the air in which alone moral sense grows and in which moral values are daily re-created.

The fact that “almost everything can be had at a price” in the market, that “the higher values of life” are “brought into the ‘cash nexus,’” is not to be regretted, says Hayek, but celebrated. By honoring the notion “that life and health, beauty and virtue, honor and peace of mind, can often be preserved only at considerable material cost,” the economy elevates those values, reminding us that they cannot be had on the cheap. By forcing us “to make the material sacrifices necessary to protect those higher values against all injury,” the economy also serves as divining rod of our morality, revealing to us what we truly believe and value.

What makes electoral politics, by contrast, such a dismal measure of moral value is that politicians promise their constituents everything without asking them to sacrifice anything.

The periodical election of representatives, to which the moral choice of the individual tends to be more and more reduced, is not an occasion on which his moral values are tested or where he has constantly to reassert and prove the order of his values and to testify to the sincerity of his profession by the sacrifice of those of his values he rates lower to those he puts higher.

In this polysemous discourse of value, we see that mix of elements—moral and economic, material and philosophical—that the labor question had galvanized and that the Austrians and Nietzsche in response sought to reorder and rearrange. What divides me from my critics is that they either don’t know or don’t care about that context and the project it provoked. They wish to assimilate the Austrians to a more circumspect tradition, which has little interest in this nexus of moral and economic power and the cultural politics of which it is a part. That’s not an illegitimate enterprise—action intellectuals construct usable pasts for themselves all the time—but it comes at a cost: It cannot account for much of what the Austrians wrote. My critics can hold onto their beliefs by ignoring inconvenient parts of the text, but they run the risk of repeating the mistakes of an earlier generation of Hayek readers. “People still tend to go off half-cocked about it,” Hayek’s editor wrote about critics of The Road Serfdom in 1945. “Why don’t they read it and find out what Hayek actually says?” Indeed.

Conclusion

I’m a historically oriented political theorist who has argued that there’s a surprising unity on the right across time and space. This is a controversial thesis, no more so than when it comes to Mises and Hayek and the followers they’ve inspired on the right. Though I didn’t initially approach conservative defenders of the market with that thesis in mind—for many years, I thought the opposite—I now believe the evidence upholds rather than refutes that thesis.

I recognize the heterodoxy of this reading of the Austrians as well as the perils and pitfalls, which John Holbo has described so well, of my argument about elective affinities. Even so, I’m surprised by the personal nature of some of the criticism I have received. It’s not simply that these critics think I’m wrong. They go further, claiming my alleged errors are signs of my questionable character and second-rate mind. Matt Zwolinski, for example, accuses me (falsely and unfairly, as I pointed out to him in an email) of deliberately misrepresenting data to fit my thesis, an offense “indicative” of more general shortcomings. Goldman accuses me of trying to “dazzle readers who know little intellectual history with a flurry of impressive names.” Like Zwolinski, he sees my article as a symptom of larger failings: “As in The Reactionary Mind, Robin assigns guilt by association (or insinuation).” Vallier agrees with that claim, and chalks it and other supposed lapses up to my “career-long attempt to shoehorn every non-leftist into a single group of people who hate equality.” Jason Brennan has publicly urged Chris Bertram to have me kicked off the Crooked Timber blog because I’m “intellectual corrupt” and my work—a term Brennan surrounds in scare quotes—is “bad in the way that first-year undergraduate essays aren’t up to snuff.”

It’s jarring to hear this kind of talk from accomplished academics rather than mindless trolls. Particularly when their case against me is so flimsy. It would be one thing if I had made errors of the sort that can only be ascribed to epic malfeasance or malpractice. But as I’ve shown, there’s much evidence to support my interpretations. If anything it seems to be my critics who are insufficiently acquainted with the material about which they so confidently pronounce. Even if one disagrees with me about Nietzsche and the Austrians, it’s difficult to see how one could see in the disagreement anything more than an academic dispute: we simply read the texts differently. That my critics would leap so quickly over that interpretation of our disagreement is telling. But of what?

One possibility is that my work unsettles the boundaries so many libertarians have drawn around themselves. (The liberal-ish conservative Goldman is a different matter; in his case, I think the problem is simply a lack of familiarity and experience with these texts.) Like some of their counterparts outside the academy, at Reason and elsewhere, academic libertarians often like to describe themselves as neither right nor left—a political space, incidentally, with some rather unwholesome precedents—or as one-half of a dialogue on the left, where the other half is Rawlsian liberalism or analytical Marxism. What they don’t want to hear is that theirs is a voice on and of the right. Not because they derive psychic or personal gratification from how they position themselves but because theirs is a political project, in which they borrow from the left in order to oppose—or all the while opposing—the main projects of the left.

That kind of politics has a name. It’s called conservatism.

June 18, 2013

Edward Snowden’s Retail Psychoanalysts in the Media

As soon as the Edward Snowden story broke, retail psychoanalysts in the media began to psychologize the whistle-blower, identifying in his actions a tangled pathology of motives. Luckily, there’s been a welcome push-back from other journalists and bloggers.

The rush to psychologize people whose politics you dislike, particularly when those people commit acts of violence, has long been a concern of mine. I wrote about it just after 9/11, when the media put Mohamed Atta on the couch.

I also wrote about it in this review of the New Yorker writer Jane Kramer’s Lone Patriot, her profile of the militia movement.

In October 1953, literary critic Leslie Fiedler delivered an exceptionally nasty eulogy for Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in the pages of the London-based magazine Encounter. Though the Rosenbergs had been executed for conspiring to commit espionage, their real betrayal, claimed Fiedler, was of themselves. Committed Communists, the Rosenbergs did more than mouth the party line; they walked, talked, ate, drank, breathed and slept it. Nothing they said or did was peculiarly their own. “Their relationship to everything,” Fiedler wrote, “including themselves, was false.” Their execution was regrettable, but not particularly notable. Once they turned into marionettes, “what was there left to die?”

Fiedler’s performance stands out in the annals of literary cruelty, not for its heartlessness but for its pitch-perfect rendition of the liberal mind at bay. For whenever liberal intellectuals are confronted with political extremism, the knotty social intelligence that normally informs their work unravels. The radical is reduced to a true believer, his beliefs a litany of crazy proverbs, his personality an inscrutable paranoia. Whether the cause is communism or the Black Panthers, feminism or the abolitionists, the liberal resorts to a familiar ghost story—of the self, evacuated for the sake of an incoming ideology—where, as is true of all such tales, the main character is never the ghost but always the teller.

…

Kramer hunts for clues to these touchy forest warriors in the dank wood of individual psychology. She writes that John Pitner, the militia’s not so fearless leader, “hated to have to answer to other people.” His father was an off-balance disciplinarian. One of Pitner’s devotees never “had friends, or even a date, in high school.” Right-wing politics provide a stage for the insufficiently evolved to act out their personal, often adolescent afflictions. As Kramer writes of Pitner, “I sometimes wondered if the Washington State Militia wasn’t, at least in part, a way for him to rewrite the history of the Pitner family.” Reminiscent of Fiedler, she concludes that Pitner “didn’t have a life in any sense I recognized.”

…

She seems to find quaint and absurd Pitner’s belief that in the early days of the United States “the townspeople got together [and] if they wanted a new road, they all contributed money and they built a new road, if they wanted a new library, they all contributed money and built a new library,” unaware, apparently, that intellectuals from Tocqueville to Robert Putnam have believed much the same thing. That’s not to say that such statements are true (they’re not), but they scarcely denote some strange woodland mishegas.

…

Tromping through this political wilderness, Kramer falls prey to a New York strain of Tourette’s syndrome, ceaselessly remarking on the strangeness and ignorance of the Northwest, the provincialism and prejudice of the forest. Her sole field guide on such expeditions, which she frequently consults, contains familiar entries on the paranoid style of American politics and the authoritarian personality. The problem with such psychological arguments, of course, is that millions of men and women fit the profile but never join the militia. There are probably more than a few leaders of the Democratic Party who never had a date in high school. And need we even launch an inventory of the editorial staff at The New Yorker?

Lastly, I wrote about it at much greater length in “On Language and Violence: From Pathology to Politics,” a piece I did for Raritan in 2006. There, I wrote more generally about how intellectuals deal with violence committed by the radical right and left. But the same strictures apply to the journalistic response to Snowden.

Why is it that when confronted with extremist violence and its defenders, whether on the right or the left, analysts resort to the categories of psychology as opposed to politics, economics, or ideology? [Journalist William] Pfaff is certainly not alone in his approach: merely consider the recent round of psychoanalysis to which Al Qaeda has been subjected or Robert Lindner’s Cold War classic, The Fifty-Minute Hour, which featured an extended chapter on “Mac” the Communist. Psychological factors, of course, may influence anyone’s decision to take up arms or to speak on behalf of those who do. But those who invoke these factors tend to ignore the central tenet of their most subtle and acute analyst: that the normal person is merely a hysteric in disguise, that the rational is often irrationality congealed. If we are to go down the road of psychoanalyzing violence, why not put Henry Kissinger or the RAND Corporation on the couch too?

There is more than a question of consistency at stake here, for the choice of psychology as the preferred mode of explanation often reflects little more than our own political prejudices. Violence we favor is deemed strategic and realistic, a response to genuine political exigencies. Violence we reject is dismissed as fanatic and lunatic, the outward manifestation of some inner drama. What gets overlooked in such designations is that violence is a deeply human activity, reflecting a full range of concerns and considerations, requiring an empathic, though critical, attention to mind and world.

…

Every culture has its martyred heroes—from the first wave of soldiers at Omaha Beach, whose only goal was to wash ashore, dead but with their guns intact so that the next wave could use them, to Samson declaring that he would die with the Philistines—and its demonized enemies, its rational use of force and its psychopathic cult of violence. And in every culture it has been the job of intellectuals to keep people clear about the difference between the two. Mill did it for imperial Europe. Why should imperial America expect anything less (or more) from William Pfaff, let alone David Denby?

But perhaps we should expect our writers to do more than simply mirror the larger culture. After all, few intellectuals today divide the sexual world into regions of the normal and abnormal. Why can’t they throw away that map for violence too? Why not accept that people take up arms for a variety of reasons—some just, others unjust—and that while the choice of violence, as well as the means, may be immoral or illegitimate, it hardly takes a psychopath to make it?

In the same way that journalists call high-level leakers in the executive branch “White House officials” and low-level guys like Snowden “narcissists” or “losers,” so do they dole out accolades like “Secretary of State” to mass murderers like Henry Kissinger while holding the Snowden-like epithets in reserve for Al Qaeda, Communists, the Militia Movement, and the Weather Underground.

June 17, 2013

Rights of Labor v. Tyranny of Capital

Remember that National Labor Relations Board regulation instructing employers to post notices in their workplaces informing workers of their right to organize under the law? I described this regulation last year:

This is just a requirement that employees be informed of their rights. It doesn’t impose costs on employers, restrict their profits, regulate their operations: it just requires that working men and women be informed of their rights.

The business lobby, led by the Chamber of Commerce, has been challenging this regulation in court. Last year, it persuaded a Republican-appointed federal judge to strike it down. Last week, it had more success, persuading an even higher level of the judiciary—a three-judge panel of the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals—to strike down the regulation as an unconstitutional infringement on the liberty of employers. (It It turns out that last month another court of appeals ruled the same way.) even more expansively, claiming that the regulation violated employer free speech rights as they are said to be embodied in Section 8c of the National Labor Relations Act. (That opinion is here in pdf.)

Here are some highlights from an AP report in last week’s Washington Post:

A second federal appeals court has struck down a rule that would have required millions of businesses to put up posters informing workers of their right to form a union.

A three-judge panel of the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond ruled Friday that the National Labor Relations Board exceeded its authority when it ordered businesses to display an 11-by-17-inch notice in a prominent location explaining the rights of workers to join a union and bargain collectively to improve wages and working conditions. The posters also made clear that workers have a right not to join a union or be coerced by union officials.

More than 6 million businesses would have been subject to the rule.

The ruling was another blow to the nation’s dwindling labor unions. Last month, another federal appeals court ruled last month that the poster rule violated businesses’ free speech rights.

In that case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit sided with the National Association of Manufacturers, U.S. Chamber of Commerce and other business groups who complained that the regulation violated free speech rights by forcing employers to display labor laws in a way that some believed was too skewed in favor of unionization.

There you have it. The government requiring an employer to hang a poster informing workers of their rights is a violation of the employer’s liberty. Employers requiring employees to attend a rally in support of Mitt Romney—or otherwise instructing employees how to vote in an election—is an exercise of the employer’s liberty.

Seems like someone’s liberty is being left out.

Update (11:45 pm)

Thanks to a commenter over at Crooked Timber, I have corrected some errors I made in this post. I hadn’t read the entire two opinions before commenting here, which I should have. Instead I relied on the Post report and also wrongly conflated the 4th Circuit Court opinion of last week with the DC Circuit Court opinion from last month. My apologies.

June 14, 2013

Bob Fitch on Left v. Right

I’m not the biggest fan of Bob Fitch’s work, but this passage from an essay he wrote in New Politics—which Bhaskar Sunkara just forwarded me—is just splendid.

The aim of the Right is always to restrict the scope of class conflict — to bring it down to as low a level as possible. The smaller and more local the political unit, the easier it is to run it oligarchically. Frank Capra’s picture in A Wonderful Life of Bedford Falls under the domination of Mr. Potter illustrates the way small town politics usually works. The aim of conservative urban politics is to create small towns in the big city: the local patronage machines run by the Floyd Flakes and the Pedro Espadas.

The genuine Left, of course, seeks exactly the opposite. Not to democratize the machines from within but to defeat them by extending scope of conflict: breaking down local boundaries; nationalizing and even internationalizing class action and union representation. As political scientist E.E. Schattschneider wrote a generation ago: “The scope of labor conflict is close to the essence of the controversy.” What were the battles about industrial and craft unionism; industry wide bargaining sympathy strikes, he asked, but efforts to determine “Who can get into the fight and who is excluded?”

Think you have nothing to hide from surveillance? Think again.

People often say that they don’t think government surveillance is such a big deal because they have nothing to hide. They post on Facebook or Twitter, their life is an open book.

What they don’t realize, as this excellent article points out (h/t Chase Madar), is that they might very well have something to hide. And the reason they don’t realize that is that they—like all of us—have no clue as to just how extensive the federal criminal code is.

The US criminal code is scattered across 27,000 pages. And that doesn’t include the roughly 10,000 additional administration regulations the government has promulgated. So extensive and sprawling are these laws and regulations that the Congressional Research Service cannot even count how many federal crimes there are.

This can have grave consequences: not for your privacy but for your immunity from government harassment and coercion.

As Justice Breyer puts it:

The complexity of modern federal criminal law, codified in several thousand sections of the United States Code and the virtually infinite variety of factual circumstances that might trigger an investigation into a possible violation of the law, make it difficult for anyone to know, in advance, just when a particular set of statements might later appear (to a prosecutor) to be relevant to some such investigation.

And as the author of the piece goes onto comment:

For instance, did you know that it is a federal crime to be in possession of a lobster under a certain size? It doesn’t matter if you bought it at a grocery store, if someone else gave it to you, if it’s dead or alive, if you found it after it died of natural causes, or even if you killed it while acting in self defense. You can go to jail because of a lobster.

If the federal government had access to every email you’ve ever written and every phone call you’ve ever made, it’s almost certain that they could find something you’ve done which violates a provision in the 27,000 pages of federal statues or 10,000 administrative regulations. You probably do have something to hide, you just don’t know it yet.

The selective invocation and application of criminal prosecutions and penalties is one of the oldest tools of repressive government. (Anyone wanting a refresher should consult Otto Kirchheimer’s classic discussion of “patterns of prosecution” in his Political Justice: The Use of Legal Procedures for Political Ends. As Kirchheimer writes, “Modern administrative practices create infinite ways to become liable to criminal prosecution.”) The sheer sprawl of federal (and don’t forget state and local) law—and the surveillance of men and women that now accompanies that sprawl—only enables this furhter.

June 13, 2013

Theory and Practice at NYU

New York University’s mission is to be an international center of scholarship, teaching and research defined by a culture of academic excellence and innovation. That mission involves retaining and attracting outstanding faculty, encouraging them to create programs that draw the best students, having students learn from faculty who are leaders in their fields, and shaping an intellectually rich environment for faculty and students both inside and outside the classroom. In reaching for excellence, NYU seeks to take academic and cultural advantage of its location in New York City and to embrace diversity among faculty, staff and students to ensure the widest possible range of perspectives, including international perspectives, in the educational experience.

It is ironic that at a time when sustaining the university as sanctuary is so important to society at large, society itself has unleashed forces which threaten the vitality if not the existence of that sacred space….

Forces outside our gates threaten the sanctity of the dialogue on campus. Begin with an obvious example. Every university president, and most deans, at some point have to face sometimes enormous external pressure because a controversial speaker is coming to campus. Inviting speakers from the right or from the left, from the fringes or even from the majority, often attracts varying degrees of protest and accompanying demands that the speaker be banned.

…

Frequently the external pressure is not reserved for protesting visiting speakers. Once unleashed, those who would exclude or punish certain views are more than willing to apply their muscle in an attempt to silence members of the university’s faculty or other members of the community.

…

At the same time, again in the name of security, we see an increasing official intolerance toward foreign professors and students, with new immigration restrictions which bear no apparent relation to genuine security concerns but which certainly hamper the capacity of America’s universities to bring into the conversation on campus those who are most talented, regardless of their country of origin. Foreign nationals interested in coming to our universities face longer application periods, extensive background checks, and constant monitoring; and many perfectly innocent professors and students effectively have been denied entry through burdensome and lengthy application procedures—and, astonishingly, some simply have been seeking to return after brief visits home to universities where they already have spent months or even years. The result: the Institute of International Education now reports that the number of foreign nationals coming to teach and study in the United States has all but stagnated, reversing a fifty-year trend of increased enrollment and thereby depleting our capacity to understand other cultures and diminishing our chance to have them understand us.

Today’s New York Post:

NYU isn’t letting a pesky thing like human rights stand in the way of its expansion in China.

The university has booted a blind Chinese political dissident from its campus under pressure from the Communist government as it builds a coveted branch in Shanghai, sources told The Post.

Chen Guangcheng has been at NYU since May 2012, when he made a dramatic escape from his oppressive homeland with the help of Hillary Rodham Clinton.

But school brass has told him to get out by the end of this month, the sources said.

Chen’s presence at the school didn’t sit well with the Chinese bureaucrats who signed off on the permits for NYU’s expansion there, the sources said.

June 11, 2013

David Brooks: The Last Stalinist

David Brooks disapproves of NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden.

Snowden’s actions, Brooks says, are a betrayal of virtually every commitment and connection Snowden has ever made: his oath to his country, his promise to his employer, his loyalty to his friends, and more.

But in one of those precious pirouettes of paradox that only he can perform, Brooks sees those betrayals as a symptom of a deeper pathology: Snowden’s inability to make commitments and connections.

According to The Washington Post, he has not been a regular presence around his mother’s house for years. When a neighbor in Hawaii tried to introduce himself, Snowden cut him off and made it clear he wanted no neighborly relationships. He went to work for Booz Allen Hamilton and the C.I.A., but he has separated himself from them, too.

Though thoughtful, morally engaged and deeply committed to his beliefs, he appears to be a product of one of the more unfortunate trends of the age: the atomization of society, the loosening of social bonds, the apparently growing share of young men in their 20s who are living technological existences in the fuzzy land between their childhood institutions and adult family commitments.

If you live a life unshaped by the mediating institutions of civil society, perhaps it makes sense to see the world a certain way: Life is not embedded in a series of gently gradated authoritative structures: family, neighborhood, religious group, state, nation and world. Instead, it’s just the solitary naked individual and the gigantic and menacing state.

This lens makes you more likely to share the distinct strands of libertarianism that are blossoming in this fragmenting age: the deep suspicion of authority, the strong belief that hierarchies and organizations are suspect, the fervent devotion to transparency, the assumption that individual preference should be supreme.

This is an old argument on the communitarian right and left: the loss of social bonds and connections turns men and women into the flotsam and jetsam of modern society, ready for any reckless adventure, no matter how malignant: treason, serial murder, totalitarianism.

It’s mostly bullshit, but there’s a certain logic to what Brooks is saying, albeit one he might not care to face up to.

In the long history of state tyranny, it is often those who are bound by close ties of personal connection to family and friends that are most likely to cooperate with the government: that is, not to “betray” their oaths to a repressive regime, not to oppose or challenge authoritarian rule. Precisely because those ties are levers that the regime can pull in order to engineer an individual’s collaboration and consent.

Take the Soviet Union under Stalin. Though there’s a venerable tradition in social thought that sees Soviet totalitarianism as the product of atomized individuals, one of the factors that made Stalinism possible was precisely that men and women were connected to each other, that they were in families and felt bound to protect each other. To protect each other by cooperating with rather than opposing Stalin.

Nikolai Bukharin’s confession in a 1938 show trial to an extraordinary career of counterrevolutionary crime, crimes he clearly did not commit, has long served as a touchstone of the manic self-liquidation that was supposed to be communism. It has inspired such treatments as Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Humanism and Terror, and Godard’s La Chinoise. Yet contrary to the myth that Bukharin somehow chose to sacrifice himself for the sake of the cause, Bukharin was brutally interrogated for a year and he was repeatedly threatened with violence against his family. In the end, the possibility that a confession might save them, if not him, proved to be potent. (1)

Threats against family members were one of the most effective means for securing cooperation with the Soviet regime; in fact, many of those who refused to confess had no children. As I wrote in Fear: The History of a Political Idea:

Stalin corralled many individuals to cooperate with his tyranny by threatening their families, and had less success among those with no families. In a 1947 letter, the head of Soviet counterintelligence recommended invoking suspects’ “family and personal ties” during interrogation sessions. Soviet interrogators would put on their desks, in full view, the personal effects of suspects’ relatives as well as a copy of a decree legalizing the execution of children. (2)

It wasn’t just under Stalin that family ties could be leveraged like this. The entire history of McCarthyism, that sordid story of the blacklist and naming names, is littered with similar concerns, albeit of a less lethal variety.

Sterling Hayden—best known for his roles as General Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove and the corrupt Captain McCluskey in The Godfather—named seven names (including his former lover) in part because he was worried that if he didn’t cooperate with the government he might lose custody of his children (he was in the middle of divorce proceedings.) (3)

More often, those who cooperated with the government did so because they feared they wouldn’t be able to support their families. That was certainly the case with Roy Huggins, a now forgotten screenwriter, producer, and director, who gave us television shows like The Fugitive and The Rockford Files. Huggins named 19 names to HUAC—though he refused to spell them for the committee, prompting Victor Navasky to drily comment that Huggins deemed it more principled “to give the names but not the letters.” Though Huggins daydreamed of the political theater of going to prison rather than betray his comrades—witnesses refusing to name names could be cited for contempt of Congress and then be tried, convicted, and jailed—he worried too much about his family to resist: “Who the hell is going to take care of two small children, a mother, and a wife, all of whom are totally dependent on me?” (4)

As Elia Kazan deliberated over whether to name names (he eventually did), he told the producer Kermit Bloomgarden—who was responsible for bringing such plays as Death of a Salesman, The Diary of Anne Frank, and Equus to the American stage—that “I’ve got to think of my kids.” To which Bloomgarden responded, “This too shall pass, and then you’ll be an informer in the eyes of your kids, think of that.” And while Kazan had other options that would have kept his family afloat, as did writers who could write under pseudonyms, that was not the case with well known actors like Lee J. Cobb, who declared “It’s the only face I have.” Or Zero Mostel, who said, “I am a man of thousand faces, all of them blacklisted.” (Cobb named names. Mostel did not.) (5)

But it’s not just family connections that do the enabling work of state repression. Other trusted figures in our lives—teachers and preachers, lovers and therapists, even lawyers—can be used by the state (or can make themselves useful to the state) to encourage us to cooperate, to remind us that our local obligations to family and friends, to partners and loved ones, trump our larger moral and political commitments.

Hayden’s example is again instructive. As I wrote in Fear:

The more immediate influences on Hayden’s decision, however, were Martin Gang, his lawyer, and Phil Cohen, his therapist. When Hayden first began to suspect that he was being blacklisted, he turned to Gang for advice. Gang suggested that he draft a letter to J. Edgar Hoover, explaining his past involvement in the party and expressing sincere repentance. Cooperating with the FBI, said Gang, would keep Hayden under HUAC’s radar and out of the television lights. Unconvinced, Hayden turned to Cohen, who assured him that Gang’s recommendation was reasonable. So advised, Hayden submitted the letter. But on the day he was scheduled to speak with the FBI, he had second thoughts. “Martin,” he told his lawyer,

“I still don’t feel right about –”

“Sterling, now listen to me. We’ve been over this thing time and time again. You make entirely too much of it. The time to have felt this way was before we wrote the letter.”

“Yes, I guess you’re right.”

“You know I’m right. You made the mistake. Nobody told you to join the Party. You’re not telling the F.B.I. anything they don’t already know.”

Hayden spoke with the FBI, which only made him feel worse and turned him against his therapist. “I’ll say this, too,” he told Cohen, “that if it hadn’t been for you I wouldn’t have turned into a stoolie for J. Edgar Hoover. I don’t think you have the foggiest notion of the contempt I have had for myself since the day I did that thing.” Not long after, HUAC issued him a subpoena. Cohen again tried to pacify him. “Now then,” said Cohen, “may I remind you there’s really not much difference, so far as you yourself are concerned, between talking to the F.B.I. in private and taking the stand in Washington. You have already informed, after all. You have excellent counsel, you know.” Again, Hayden capitulated.

And as I went onto conclude:

In recent years, scholar and writers have extolled the virtues of an independent civil society, in which private circles of intimate association are supposed to shield men and women from a repressive state. To the extent that these links are explicitly political and oppositional, this account of civil society holds true. Few of us have the inner strength or sustaining vision to opt for the lonely path of a Socrates or a Solzhenitsyn. Deprived of the solidarity of comrades, our visions seem idiosyncratic and quixotic; fortified by our political affiliations, they seem moral and viable.

But what analysts of civil society often ignore is the experience of Hayden and others like him, how our everyday connections can echo or amplify our inner counsels of fear. “Friends and family worry about me,” writes Mino Akhtar, a Pakistani American management consultant in New Jersey who has campaigned against the war in Iraq and the secret detention of Arabs and Muslims after 9/11. “They tell me to be careful, that I’m taking risks. They say that if my face and name keep coming up in public I won’t get any more consulting jobs. I think about that sometimes. You work hard to establish yourself, you have the good job, big home, these mortgage payments; it’s scary to think you can lose it all.”

It is precisely the nonpolitical, personal nature of these connections that makes them so powerful a voice for cooperation. Afraid, we think about our lives and livelihoods, loved ones and friends, and we doubt the meaning or efficacy of our politics. When comrades advise us to resist, we discard their counsel as so much political rhetoric; when trusted intimates advise us to submit, we hear the innocent, apolitical voice of natural reason. Because these counsels of submission are not seen as political recommendations, they are ideal packages of covert political transmission.

Back to David Brooks. Brooks likes to package his strictures in the gauzy wrap of an apolitical communitarianism. But Brooks is also, let us not forget, an authority- and state-minded chap, who doesn’t like punks like Snowden mucking up the work of war and the sacralized state. And it is precisely banal and familial bromides such as these—the need to honor one’s oaths, the importance of family and connection—that have underwritten popular collaboration with that work for at least a century, if not more.

Stalin understood all of this. So does David Brooks.

Notes

(1) J. Arch Getty and Oleg V. Naumov, The Road to Terror: Stalin an the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 40, 48-49, 369-70, 392-399, 411, 417-419, 526; Stephen F. Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888-1938 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 375-380; The Great Purge Trial, ed. Robert C. Tucker and Stephen F. Cohen (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1965), xlii-xlviii.

(2) Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Thirties (London: Macmillan, 1968), 142, 301; Getty and Naumov, 418, 526; Sheila Fitzpatrick, Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 25; Anne Applebaum Gulag: A History (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 139; Cohen, 375; Adam Hochschild, The Unquiet Ghost: Russians Remember Stalin (New York: Viking, 1994), 13, 21-22; Tina Rosenberg, The Haunted Land: Facing Europe’s Ghosts After Communism (New York: Vintage, 1995), 28-29.

(3) Sterling Hayden, Wanderer (New York: Knopf, 1963), 371-372; Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund, The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960 (Garden City: Anchor Press, 1980), 386-389; Victor Navasky, Naming Names (New York: Penguin, 1980), 100-101.

(4) Navasky, 258, 260, 281.

(5) Navasky, 178, 201-202.

June 10, 2013

Snitches and Whistleblowers: Who would you rather be?

Who would you rather be?

Edward Snowden

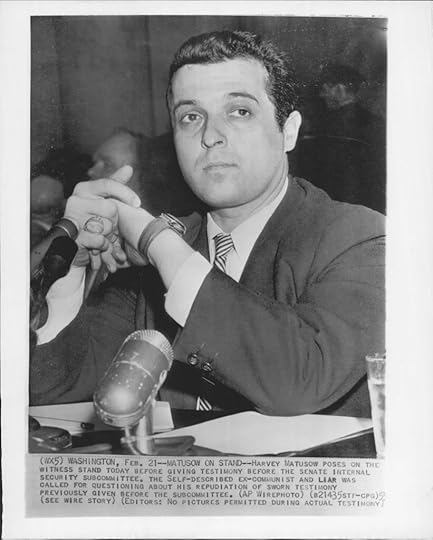

Or this guy?

Harvey Matusow testifying before Senate Internal Subcommittee

The twentieth century was the century of Matusow, Kazan, and other assorted informers, informants, and snitches, behind the Iron Curtain, in Nazi Germany, in Latin America, in the United States. Everywhere.

Let the 21st be the century of Snowden, Manning, and more.

June 6, 2013

Jumaane Williams and the Brooklyn College BDS Controversy Revisited

There’s a long profile of NYC Councilman Jumaane Williams in BKLYNR, a new Brooklyn-based magazine, by Eli Rosenberg. It’s a fascinating read of a fascinating politician, who played a less than fascinating role during the Brooklyn College BDS controversy. Williams is a former student of mine, and he and I wound up in a heated Twitter argument about his role.