Timothy Ferriss's Blog, page 101

October 7, 2014

Tony Robbins and Peter Diamandis (XPRIZE) on the Magic of Thinking BIG

If you want to 10x or 100x your results and impact, this interview with Tony Robbins and Peter Diamandis is a must listen.

Where else can you find two people who regularly advise everyone from Serena Williams to Bill Clinton, from NASA to the world’s fastest growing companies? Here’s their next project, if you want a sneak peek.

Stream with the player below:

If you can’t see the above, here are other ways to listen:

Listen to it on iTunes.

Stream here.

Download is as MP3 by right clicking here and choosing “save as”.

This podcast is brought to you by 99Designs, the world’s largest marketplace of graphic designers. Did you know I used 99Designs to rapid prototype the cover for The 4-Hour Body? Here are some of the impressive results.

Also, how would you like to join me and billionaire Richard Branson on his private island for mentoring? It’s coming up soon, and it’s all-expenses-paid. Click here to learn more. It’s worth checking out.

Now, on to this episode’s guests… Note that show links are included below their bios.

TONY ROBBINS

Tony Robbins has consulted or advised international leaders including Nelson Mandela, Mikhail Gorbachev, Margaret Thatcher, Francois Mitterrand, Princess Diana, and Mother Teresa. He has consulted members of two royal families, members of the U.S. Congress, the U.S. Army, the U.S. Marines and three U.S. Presidents, including Bill Clinton. Other celebrity clients include Serena Williams, Andre Agassi, golf legend Greg Norman, and Leonardo DiCaprio. Robbins also has developed and produced five award-winning television infomercials that have continuously aired on average every 30 minutes, 24 hours a day somewhere in North America since their initial introduction in April 1989.

PETER DIAMANDIS

Dr. Peter Diamandis has been named one of “The World’s 50 Greatest Leaders” by Fortune Magazine.

In the field of Innovation, Diamandis is Chairman and CEO of the X PRIZE Foundation, best known for its $10 million Ansari X PRIZE for private spaceflight. Today the X PRIZE leads the world in designing and operating large-scale global competitions to solve market failures. Diamandis is also the Co-Founder and Vice-Chairman of Human Longevity Inc. (HLI), a genomics and cell therapy-based diagnostic and therapeutic company focused on extending the healthy human lifespan. He is also the Co-Founder and Executive Chairman of Singularity University, a graduate-level Silicon Valley institution that studies exponentially growing technologies, their ability to transform industries and solve humanity’s grand challenges. In the field of commercial space, Diamandis is Co-Founder/Co-Chairman of Planetary Resources, a company designing spacecraft to enable the detection and mining of asteroid for precious materials.

Scroll below for all show notes. Tons of amazing links and goodies…

Enjoy!

Who should I interview next? Please let me know on Twitter or in the comments.

Do you enjoy this podcast? If so, please leave a short review here. It keeps me going…

Subscribe to The Tim Ferriss Show on iTunes.

Non-iTunes RSS feed

Selected Links, Including Projects, Books, Etc.

BE SURE TO VISIT THE FIRST TWO TO SEE WHAT WE’RE WORKING ON

BOOKS MENTIONED

The Spirit of St. Louis by Charles Lindbergh

Man Who Sold the Moon by Robert A. Heinlein

The Singularity is Near by Ray Kurzweil

As a Man Thinketh by James Alan

Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl

The Fourth Turning by William Strauss

Generations by William Strauss

###

QUESTION OF THE DAY: What books or resources have most inspired you to think BIGGER, to 10x your results or impact?

October 3, 2014

How to Travel to 20+ Countries…While Building a Massive Business in the Process

[Preface: The above is a pic of Necker Island, Richard Branson's private island. Would you like to join me and Richard Branson on Necker for a week of mentoring? Here are the details on how you can get an all-expenses-paid trip. It'd be great to meet you.]

The following is a guest post by Breanden Beneschott, co-founder and COO of Toptal, a marketplace for top developers. I have no affiliation with the company, but I found Breanden’s story fascinating.

This post covers how he traveled through 20+ countries while building a company, experiencing the best the world had to offer. His how-to instructions include travel tools, shortcuts, and all the non-obvious systems you’d expect from a great engineer.

For context and to kick us off, an excerpt from Breanden’s email to me might be helpful. Edited down a bit, here it is:

We started Toptal 3.5 years ago from my dorm room at Princeton (I think a week after I met you briefly in Ed Zschau’s class [TIM: I guest lectured there], where I decided to do my final paper on the company). By the time I finished school six months later, Toptal was doing well with clients and engineers all over the world. We decided to move to Eastern Europe and keep practicing what we were preaching, in terms of scaling a company via a completely distributed team. Doing so allowed us to funnel nearly all profits back into growing the business (and live like kings for next to nothing). We are now approx 60 team members and 1000 engineers (e.g., top-100 Rails contributors, guys from CERN, university professors, etc.) working with thousands of clients (e.g., Beats, Zendesk, Artsy, JPMorgan, etc.) with virtually zero restrictions when it comes to location.

People constantly ask me how I manage to travel and work the way I do. I had always hoped outside (non-Toptal) people would see this post and be inspired to join us or pick up and travel while working on their own big ideas.

BTW, I do expect that comments will highlight the ambiguity of the “growing hundreds of percent year over year” statement. We’ve very deliberately avoided most press until now, as we didn’t want to build a company based on PR, and we’ve never publicly announced our revenue. Right now we are well north of XXM/yr [TIM: I replaced the actual number with XX but, suffice to say, they have 9-figure acquisition offers and term sheets] and growing like a weed, but few non-core people know that. So do you see any tactful way of preempting those sorts of comments?

Yep, I do. I could include your email like I just did.

Now, on to the details. This is a good one, folks, so keep reading. Breanden’s tips apply mostly to the mobility and travel pieces of the puzzle; if you’d like additional business-building tools, I highly suggest this article on rapid testing (in a weekend), this article on hacking Kickstarter, and this post on all aspects of marketing and PR.

Enter Breanden

[The following is based on my personal experience as a traveling engineer and founder. Feel free to contact me any time at breanden [at] toptal [dot] com.]

I’ve lived and worked remotely in approximately 29 countries since I finished school three years ago. I’ve been running Toptal, a venture funded company growing hundreds of percent year over year—all from my laptop, phone, and tablet.

Croatia · Bosnia · Italy · France · Switzerland · Germany · Austria · Georgia · Romania · Serbia · Slovenia · Spain · Ukraine · Morocco · Brazil · Canada · Paraguay · Argentina · Uruguay · New Zealand · Australia · Hong Kong · USA · England · Turkey · Chile · Slovakia · Czech Republic · Lebanon

I don’t have an apartment. I don’t have a house. I don’t have an office.

I hate the cold, so I summer hop.

Everywhere I go, I meet great engineers who end up becoming invaluable parts of Toptal.

I encourage everyone in Toptal to travel, and a lot of us do. Some of us travel for week long “breaks” throughout the year, and some of us live out of a suitcase like me. Few of us ever stop working for a full day.

I’m writing this because…

I was repeatedly asked if I had some sort of guide or checklist for traveling/working the way I do. Especially for first-timers, the idea of adventuring while working can be daunting. There are a lot of details to consider, and I’ve learned a lot from my own trial-and-error.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized a guide like this was actually missing.

The 4-Hour Workweek was great, and I like Tim Ferriss a lot. But what if you want to work more than 4 hours a week? I like working crazy hours. I don’t want a lifestyle company. I want to solve hard problems. I want to build something big and give it my all.

I want a book on how to create a billion-dollar company while becoming a fighter pilot. (I’m trying to build a world-changing company while becoming a professional polo player.) That would be inspiring. But until it comes, maybe this post will be helpful to a few people.

Why travel?

Because it’s unbelievably awesome.

Now is the time: it’s feasible like never before. You can put in a full work day no matter where you are. If you’re standing in line for airport security, you can listen to The Changelog. If you’re in the Hungarian countryside, you can work perfectly via 4G. If you’re flying across the world, you can work from the moment you buckle in to the moment you stand up to get off the plane. The airport will have WiFi to push a commit if your plane didn’t. You can travel while producing some of the best work of your career, and you will grow with every new stamp in your passport.

The secret benefit: avoiding burnout.

I don’t take vacations. I don’t want to work hard to build a company that makes lots of money so I can piss off and go on holiday. I’m at a start-up. I’m a part of it, and it’s a part of me. This is a marathon, and there will be a winner. Traveling and working allows you to go non-stop. There is no burnout. There’s no staring at a clock or calendar waiting for the EOD/weekend/break. You’re refreshed weekly, and you can hone your focus and structure your time so you are a cross functional superstar who never stops learning.

Playing polo (often with Toptal developers) in Argentina. Total cost for sponsorship: 400 pesos (~$40) for t-shirts.

Length of travel

I usually stay in places for ~3 months. Why?

It fits under the constraints of the typical tourist visa.

More on that in a second.

It gives you time to relax and focus in between the stressful travel sessions.

Power trips of 9 countries in 3 weeks are for students on holiday. You need to be able to stop traveling and focus on work.

It gives you time to really explore and get to know a place and people.

There are almost certainly local tech meetups, and there are likely to be other Toptal engineers wherever you go now as well.

You can really try local culture.

Learn to play polo in Argentina. Practice capoeira in Brazil. Go to trance festivals in Europe. If you don’t know where to start, join Internations and go to expat meetups.

It helps with costs.

Trips of this duration help you negotiate special medium-term deals on apartments, cars, vespas, etc.

Who to go with

A close friend/colleague

You can split costs for a lot of things like cars, hotels, etc. You can also split the research and push each other to do things you might not do yourself (like go out to new places, go on adventures, rent a boat, etc.).

Alone

Not for the faint of heart, but not everyone has the flexibility you do as a software engineer. If you don’t have anyone to go with, don’t let it stop you. With Internations and a network like Toptal, you can almost certainly go anywhere and immediately find people with lots in common.

A girlfriend/boyfriend

Can be by far the most expensive option, but it’s probably the most rewarding and fun. Nothing brings compatible people together like adventure. However, nothing drives incompatible people apart like stress, so be careful. The other thing to consider is whether your significant other will also be working during your travels. If so, that’s tremendous, and you are very lucky. If not, that can be very hard. The added costs of having a dependent aside, you don’t want to be in a position where someone resents you for constantly working during what they’ve misunderstood to be a vacation. Luckily there are many interesting careers in addition to software engineering that are now doable remotely (e.g., executive assistant, translator, designer, tutor, entrepreneur, etc.).

What to take

Backpack

Always a carry on. Pretty much always with me.

How to Travel to 20+ Countries…And Build a Massive Business in the Process

[Preface: The above is a pic of Necker Island, Richard Branson's private island. Would you like to join me and Richard Branson on Necker for a week of mentoring? Here are the details on how you can get an all-expenses-paid trip. It'd be great to meet you.]

The following is a guest post by Breanden Beneschott, co-founder and COO of Toptal, a marketplace for top developers.

This post covers how he built a massive company while traveling through 20+ countries, experiencing the best the world has to offer. His how-to instructions include travel tools, shortcuts, and all the non-obvious systems you’d expect from a great engineer.

For context and to kick us off, an excerpt from Breanden’s email to me might be helpful. Edited down a bit, here it is:

We started Toptal 3.5 years ago from my dorm room at Princeton (I think a week after I met you briefly in Ed Zschau’s class [TIM: I guest lectured there], where I decided to do my final paper on the company). By the time I finished school six months later, Toptal was doing well with clients and engineers all over the world. We decided to move to Eastern Europe and keep practicing what we were preaching, in terms of scaling a company via a completely distributed team. Doing so allowed us to funnel nearly all profits back into growing the business (and live like kings for next to nothing). We are now approx 60 team members and 1000 engineers (e.g., top-100 Rails contributors, guys from CERN, university professors, etc.) working with thousands of clients (e.g., Beats, Zendesk, Artsy, JPMorgan, etc.) with virtually zero restrictions when it comes to location.

People constantly ask me how I manage to travel and work the way I do. I had always hoped outside (non-Toptal) people would see this post and be inspired to join us or pick up and travel while working on their own big ideas.

BTW, I do expect that comments will highlight the ambiguity of the “growing hundreds of percent year over year” statement. We’ve very deliberately avoided most press (we don’t want to build a company based on PR), and we’ve never publicly announced our revenue. Right now we are well north of XXM/yr [TIM: I replaced the actual number with XX, but it's impressive] and growing like a weed, but few non-core people know that. So do you see any tactful way of preempting those sorts of comments?

Yep, I do. I could include your email like I just did. Gin helps with such decisions.

Now, on to the details. This is a good one, folks, so keep reading…

Enter Breanden

[The following is based on my personal experience as a traveling engineer and founder. Feel free to contact me any time at breanden [at] toptal [dot] com.]

I’ve lived and worked remotely in approximately 29 countries since I finished school three years ago. I’ve been running Toptal, a venture funded company growing hundreds of percent year over year—all from my laptop, phone, and tablet.

Croatia · Bosnia · Italy · France · Switzerland · Germany · Austria · Georgia · Romania · Serbia · Slovenia · Spain · Ukraine · Morocco · Brazil · Canada · Paraguay · Argentina · Uruguay · New Zealand · Australia · Hong Kong · USA · England · Turkey · Chile · Slovakia · Czech Republic · Lebanon

I don’t have an apartment. I don’t have a house. I don’t have an office.

I hate the cold, so I summer hop.

Everywhere I go, I meet great engineers who end up becoming invaluable parts of Toptal.

I encourage everyone in Toptal to travel, and a lot of us do. Some of us travel for week long “breaks” throughout the year, and some of us live out of a suitcase like me. Few of us ever stop working for a full day.

I’m writing this because…

I was repeatedly asked if I had some sort of guide or checklist for traveling/working the way I do. Especially for first-timers, the idea of adventuring while working can be daunting. There are a lot of details to consider, and I’ve learned a lot from my own trial-and-error.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized a guide like this was actually missing.

The 4-Hour Workweek was great, and I like Tim Ferriss a lot. But what if you want to work more than 4 hours a week? I like working crazy hours. I don’t want a lifestyle company. I want to solve hard problems. I want to build something big and give it my all.

I want a book on how to create a billion-dollar company while becoming a fighter pilot. (I’m trying to build a world-changing company while becoming a professional polo player.) That would be inspiring. But until it comes, maybe this post will be helpful to a few people.

Why travel?

Because it’s unbelievably awesome.

Now is the time: it’s feasible like never before. You can put in a full work day no matter where you are. If you’re standing in line for airport security, you can listen to The Changelog. If you’re in the Hungarian countryside, you can work perfectly via 4G. If you’re flying across the world, you can work from the moment you buckle in to the moment you stand up to get off the plane. The airport will have WiFi to push a commit if your plane didn’t. You can travel while producing some of the best work of your career, and you will grow with every new stamp in your passport.

The secret benefit: avoiding burnout.

I don’t take vacations. I don’t want to work hard to build a company that makes lots of money so I can piss off and go on holiday. I’m at a start-up. I’m a part of it, and it’s a part of me. This is a marathon, and there will be a winner. Traveling and working allows you to go non-stop. There is no burnout. There’s no staring at a clock or calendar waiting for the EOD/weekend/break. You’re refreshed weekly, and you can hone your focus and structure your time so you are a cross functional superstar who never stops learning.

Playing polo (often with Toptal developers) in Argentina. Total cost for sponsorship: 400 pesos (~$40) for t-shirts.

Length of travel

I usually stay in places for ~3 months. Why?

It fits under the constraints of the typical tourist visa.

More on that in a second.

It gives you time to relax and focus in between the stressful travel sessions.

Power trips of 9 countries in 3 weeks are for students on holiday. You need to be able to stop traveling and focus on work.

It gives you time to really explore and get to know a place and people.

There are almost certainly local tech meetups, and there are likely to be other Toptal engineers wherever you go now as well.

You can really try local culture.

Learn to play polo in Argentina. Practice capoeira in Brazil. Go to trance festivals in Europe. If you don’t know where to start, join Internations and go to expat meetups.

It helps with costs.

Trips of this duration help you negotiate special medium-term deals on apartments, cars, vespas, etc.

Who to go with

A close friend/colleague

You can split costs for a lot of things like cars, hotels, etc. You can also split the research and push each other to do things you might not do yourself (like go out to new places, go on adventures, rent a boat, etc.).

Alone

Not for the faint of heart, but not everyone has the flexibility you do as a software engineer. If you don’t have anyone to go with, don’t let it stop you. With Internations and a network like Toptal, you can almost certainly go anywhere and immediately find people with lots in common.

A girlfriend/boyfriend

Can be by far the most expensive option, but it’s probably the most rewarding and fun. Nothing brings compatible people together like adventure. However, nothing drives incompatible people apart like stress, so be careful. The other thing to consider is whether your significant other will also be working during your travels. If so, that’s tremendous, and you are very lucky. If not, that can be very hard. The added costs of having a dependent aside, you don’t want to be in a position where someone resents you for constantly working during what they’ve misunderstood to be a vacation. Luckily there are many interesting careers in addition to software engineering that are now doable remotely (e.g., executive assistant, translator, designer, tutor, entrepreneur, etc.).

What to take

Backpack

Always a carry on. Pretty much always with me.

September 30, 2014

The Tim Ferriss Show: Tracy DiNunzio on Rapid Growth and Rapid Learning

This single interview with Tracy DiNunzio, founder of Tradesy, was recorded in three short parts. You can:

Listen to all three on iTunes

Download them as MP3s (right click “save as”): Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

Download the transcript (PDF, Word)

Or stream them now below (If you’re reading this in e-mail, please click here to stream):

This podcast is brought to you by The Tim Ferriss Book Club, which features a handful of books (4-6) that have changed my life. Here is the list, including free samples of every one.

Also, how would you like to join me and billionaire Richard Branson on his private island for mentoring? It’s coming up soon, and it’s all-expenses-paid. Click here to learn more. It’s worth checking out — trust me.

Now, on to this episode’s guest…

Tracy DiNunzio is a killer. She’s the self-taught founder and CEO of Tradesy.com, which has taken off like a rocket ship. She’s raised $13 million from investors including Richard Branson, Kleiner Perkins, and yours truly, and board members include the legendary John Doerr. Tradesy is on a mission to make the resale value of anything you own available on demand. Their tagline is “cash in on your closet.”

Tracy is in the trenches 24/7, making it the perfect time to ask her… How has she created such high-velocity growth? How did she recruit the investors she did? What’s been her experience as a female founder? What are her biggest mistakes made and lessons learned? This multi-part series, fueled by wine, will answer all this and more.

Even if you have no desire to start your own company, this 3-part series will get you amped to do big things.

This episode touches on a lot of cool stuff. It’s a mini-MBA in entrepreneurship, hustle, and tactics.

Scroll below for all show notes. Tons of amazing links and goodies…

Enjoy!

Who should I interview next? Please let me know in the comments by clicking here.

Do you enjoy this podcast? If so, please leave a short review here. It keeps me going…

Subscribe to The Tim Ferriss Show on iTunes.

Non-iTunes RSS feed

Show Notes and Select Links from the Episode

Tracy DiNunzio’s unlikely resume

How her business model reflects her lifestyle, and why that’s intentional

How another startup (and her bootstrapping) helped her find her husband

The story of bootstrapping her first company, Recycled Bride, and how she traded skills for food

Why the current day is the best (and worst time) to start an online company

How she funded and launched Tradesy

Why she chose venture capital rather than continuing to bootstrap

The trade-offs — the cons — of venture capital

Common mistakes Tracy made when she began pitching to investors

How the rules of dating apply to pitching investors

The creative way she found her CTO and technical co-founder… on Craigslist

Addressing the pink elephant in the room — What’s her experience as a woman in the tech start-up world?

The “Hail, Mary” that kept Tradesy going before its upswing

What attracted iconic investors like Sir Richard Branson and John Doerr to Tradesy

How to spend 13 million dollars without blowing it

Numerous resources for would-be entrepreneurs

Tracy’s advice to anyone who is unhappy in their current career

LINKS FROM THE EPISODE

Visit the Tim Ferriss Book Club to find a new book each month (or so) that’s changed my life

My book selection on Audible

Learn more about Shima-uta (The Boom song)

Get more information about Rokudenashi Blues

Tradesy

Check out the deals I’m involved with in the startup world

Learn more about Kay Brothers Amery Vineyards Block 6 Shiraz Vintage 2010 and other wines by Kay Brothers

Airbnb.com

Uber.com

More info about Chromatik

Learn more about Big Frame

Get more information about ChowNow

Listn – Listen to your friends’ music for free

Venture Hacks

Angel List

Learn more about Randy Komisar

Jobs at Tradesy

Tradesey iPhone App

Tradesey on Facebook

Tracy DiNunzio on Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn

Books Mentioned in the Episode

The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing: Violate Them at Your Own Risk! by Al Ries

The Monk and the Riddle by Randy Komisar

Good to Great and the Social Sectors: A Monograph to Accompany Good to Great by Jim Collins

The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon by Brad Stone

###

QUESTION OF THE DAY: What startup resources (books, articles, interviews) have you found most helpful or inspiring? Please share in the comments!

September 15, 2014

What I Learned Losing a Million Dollars

(Photo: Ariel H.)

(Photo: Ariel H.)

“One of the rare noncharlatanic books in finance.”

– Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of The Black Swan and Antifragile

“There is more to be learned from Jim Paul’s true story of failure than from a stack of books promising to reveal the secret formula for success…this compact volume is filled with a wealth of trading wisdom and insights.”

– Jack Schwager, author of Hedge Fund Market Wizards

The newest book in The Tim Ferriss Book Club (all five books here) is a fast read entitled What I Learned Losing a Million Dollars. It packs a wallop.

This book came into my life through N.N. Taleb, who has made several fortunes by exploiting the hubris of Wall Street. Given how vociferously he attacks most books on investing, it caught my attention that he openly praises this little book.

My first dinner with Nassim was in September of 2008. It was memorable for many reasons. We were introduced by the incredible Seth Roberts (may he rest in peace), and we sat down just as Lehman Brothers was collapsing, which Taleb had — in simple terms — brilliantly shorted. We proceeded to drinking nearly all of the Prosecco in the restaurant, while talking about life, business, and investing. Lehman Brothers would end up the largest bankruptcy filing in US history, involving $600+ billion in assets.

The next day, I had a massive hangover and a hunger to study Nassim. Step one was simple: reading more of what he read.

I grabbed a copy of What I Learned Losing a Million Dollars, and I’ve since read it many, many times. For less than $20, this tool has helped me avoid multiple catastrophes, and I can directly credit its influence to roughly 1/2 of my net worth (!). The ROI has been incredible.

The book — winner of a 2014 Axiom Business Book award gold medal — begins with the unbroken string of successes that helped Jim Paul achieve a jet-setting lifestyle and land a key spot with the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. It then describes the circumstances leading up to 7-figure losses, and the essential lessons he learned from it. The theme that emerges: there are 1,000,000+ ways to make money in the markets (and many of the “experts” contradict one another), but all losses appear to stem from the same few causes. So why not study these causes to help improve your odds of making and keeping money?

Even if you don’t view yourself as an “investor,” this book can help you make better decisions in life. Also, the stories, similar in flavor to Liar’s Poker, are hilarious and range from high-stakes baccarat to Arabian horse fiascos. For entertainment value alone, this book is worth the time.

I hope you enjoy — and benefit from — the lessons and laughs as much as I have.

Get the audiobook for free when you try Audible

Buy the audiobook on Audible

Buy the Kindle version

For those who enjoy both audio and Kindle, as I do, the above editions are synced with Whispersync. This means that if you get both the audio and Kindle, you can switch between the two. For instance, I like to read Kindle books on my iPhone on the subway, then pick up and listen to the audio while walking outside.

Would you be interested in interviewing the co-author, Brendan Moynihan? Brendan is a Managing Director at Marketfield Asset Management ($20 billion of assets under management) and the Senior Advisor to the Editor-in-Chief of Bloomberg News, among other things.

If you’re a journalist, blogger, podcaster, etc. interested in the book’s lessons, feel free to reach out to him at bmoynihan [at] bloomberg {dot} net.

I recently interviewed him myself for an hour about investing, how he met Jim Paul, and much more. Click below to listen to the conversation, or (if reading via email) you can click here to stream/download the MP3:

For those who want a short synopsis of the book, here you go:

Jim Paul’s meteoric rise took him from a small town in Northern Kentucky to governor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, yet he lost it all — his fortune, his reputation, and his job — in one fatal attack of excessive economic hubris. In this honest, frank analysis, Paul and Brendan Moynihan revisit the events that led to Paul’s disastrous decisions and examine the psychological factors behind bad financial practices in several economic sectors.

Paul and Moynihan’s cautionary tale includes strategies for avoiding loss tied to a simple framework for understanding, accepting, and dodging the dangers of investing, trading, and speculating.

###

September 12, 2014

Can You Rewire Your Brain In Two Weeks? One Man’s Attempt…

Can you rewire your brain in two weeks? The answer appears to be — at least partially — yes.

The following is a guest post by Shane Snow, frequent contributor to Wired and Fast Company and author of the new book SMARTCUTS: How Hackers, Innovators, and Icons Accelerate Success. Last year, he wrote about his two-week Soylent experiment, which went viral and racked up 500+ comments. He knows how to stir up controversy.

In this post, Shane tests the “brain-sensing headband” called Muse.

It’s received a lot of PR love, but does it stand up to the hype? Can it make you a calmer, more effective person in two weeks? This post tackles these questions and much more.

As many of your know, I’m a long-time experimenter with “smart drugs,” which I think are both more valuable and more dangerous that most people realize. This includes homemade brain stim (tDCS) devices (I wouldn’t recommend without supervision) and other cutting-edge tools. If you’d like to read more on these topics, please let me know in the comments.

In the meantime, I hope you enjoy Shane’s experimentation!

Enter Shane Snow

The electrodes needed to be adjusted to fit my sweaty head, which was apparently the largest size the product could accommodate.

I was sitting on a porch in palpable D.C. humidity, on a midsummer’s morning at Bolling Air Force Base, trying to get a quartet of EEG sensors to connect my brain to my Samsung Galaxy. The purple box on my screen kept blinking in and out of sync.

Inside the house, my friend’s two-year-old was jumping violently on the sofa—the same sofa that the shedding 15-pound cat named Endai and I had shared for the past week. The house was in shambles; movers were busily trucking everything away to my friend’s soon-to-be new home in New Mexico. Hence the porch.

I had been sleeping on said couch due to the abrupt ending of an 8-year relationship, which had left me stunned and homeless for the preceding three weeks. As luck would have it, the anti-anxiety pills my shrink had prescribed for me to take “as needed” were back in New York in my friend Simon’s living room. Crap. My calendar had just alerted me that I’d missed the Skype call start time for my company board meeting, right before the movers unplugged the Internet. Meanwhile, a platoon of military helicopters had decided to play what appeared to be a game of “who can hover the longest over the neighborhood”. Chuk, chuk, chuk, chuk, chuk. CHUCK. CHUCK.

My stress levels were high.

Seemed like as good a time as any to try out my new gadget: a brainwave-sensing headband called the Muse, and its companion app, Calm.

I placed the band’s centimeter-wide contact strip of electrodes against my forehead and rested the plastic against the top of my ears, fiddling with the fit until my phone finally registered a solid connection for each of the sensors, two on my temples, two behind my ears. I donned my white Audio-Technica DJ headphones and fired up the app, which in a soothing voice instructed me to sit up straight, and breeeeeeeathe.

Calm is a simple meditation exercise: Count your breaths. Don’t try to force them. Your body knows how to breathe. Simply pay attention, the female voice in my headphones told me. After Muse calibrated to my brain’s “active” state—by making me brainstorm items in a series of topics—I was given five minutes of nature sounds to breathe to. When calm and focused, I enjoyed the sound of lapping waves and birds tweeting; when my mind wandered, sturdy winds picked up and the birds flew away.

At the end of five minutes, the app confirmed: I am not very calm.

Thus began my two week experiment in brain therapy. I’d been planning on acquiring a Muse after having caught wind of its development nearly two years before, but who knew it would finally be released during the most anxious time of my adult life? Two weeks was plenty of time, Muse inventor Ariel Garten told me, for the Muse focus training exercises “to reduce perception of pain, improve memory, improve affect, reduce anxiety, and also improve emotional intelligence.”

Seemed a little good to be true, but I was willing to test it.

Electroencephalography (EEG—the recording of electrical activity emitted from the brain) has come a long way in the last 100 years, since doctors drilled holes in monkeys heads to attach sensors, and eventually glued contacts with cathode ray tubes to intact human skulls to map brain activity. They discovered that the brain emits oscillating signals of variable frequency, and the frequency of the oscillations indicates what’s happening—at a high level—in one’s mind. These “waves” are generally delineated into categories based on frequency ranges:

Delta waves: indicate deep sleep. (1-3 Hz)

Theta waves: indicate deep relaxation or meditation. (4-8 Hz)

Alpha waves: indicate a relaxed brain state, what Garten calls “an open state of mind.” (9-13 Hz)

Beta waves: indicate alert consciousness and fire up when you’re actively thinking. (14-30 Hz)

Gamma waves: indicate high alertness and are often associated with learning. (30-100 Hz)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The original purpose of EEG was the study of epilepsy. Over the decades, however, as computers improved, neuroscientists’ increasing capability to process the enormous amount of data the brain throws off allowed them to experiment with EEG for other uses, such as attention therapy.

In his 2007 book, The Brain That Changes Itself, neuroscientist Norman Doidge made mainstream the then recent (and surprising) finding that “the brain can change its own structure and function through thought and activity.” Our intelligence and tendencies are not locked in once we’re no longer children, as popular belief once held. Once our brain was wired, it could still be rewired. Doidge called it, “the most important alteration in our view of the brain since we first sketched out its basic anatomy and the workings of its basic component, the neuron.”

This adaptability factor of the brain is called “neuroplasticity.” You may have seen dubious advertisements for “brain-enhancing games” and other gimmicks that drop the term neuroplasticity in impressive-sounding (but often meaningless) marketing speak. Despite this misuse, the plasticity of our neurons is, in fact, fact. Our brains use it to wire themselves naturally, but in the past several years scientists have developed a simple procedure to “hack” them.

Neurofeedback training, or NFT as the scientists call it, is a conditioning method wherein a patient is hooked up to an EEG and shown how active her brain is, thus allowing her to concentrate on exercises that exploit neuroplasticity to build mental muscles that allow her to consciously affect her resting brain activity. Clinical studies have shown that NFT helps the majority of patients to improve their cognitive control and have also helped ADHD sufferers significantly improve their ability to focus. NFT has even been shown to have a positive effect on depression.

The two prerequisites to being able to pull off NFT are EEG sensors and a computer processor that can turn an EEG scan into real-time feedback. The electricity coming off the brain is orders of magnitude weaker than a standard AA battery, which means sensors must be powerful, delicate, and well-attached to pick anything up. Doctors have found that the skull reduces the signal significantly and thus would prefer if we didn’t have skulls (for examination purposes, that is), but have mostly settled on using wet sensors—electrodes affixed to the scalp or forehead using conductive gel.

The breakthrough that enabled a more practical, portable EEG device like the Muse claims to be, was the advent of dry sensors, or metal contacts that can use the skin’s own moisture or sweat to attain the necessary conductivity.

“Brain waves are very, very, very quiet. They’ve had to make their way all the way through your thick, thick skull,” Garten says. But sensor technology is improving at a rate that indicates we’re two to three years away from non-contact sensors, she predicts.

And in 2014, processing power is no longer a problem. “Ten years ago we were using fiber optic cable to make sure that you got this extraordinary data into what was like an egg carton and an ancient Commodore computer so that they could do all the processing,” Garten says. “Now, we can just use a phone and Bluetooth.”

The 2013 Muse prototype

When I’d first laid hands on the Muse a year and a half before, it was a chunky slab of plastic and metal. Garten and I met up at a design gallery in Manhattan for a demo of the prototype headband she’d been working on for the better part of the last decade. A Canadian fashion designer turned neuroscientist, she spoke earnestly about the potential applications for measuring one’s brainstate to ameliorate stress and perhaps one day cure ADHD and anxiety.

Garten’s prototype Muse measured the activity of these waves and output them to an iPad like a seismograph. After I donned the plastic headband, I watched in real time as slowing my breathing or concentrating on something or simply talking affected the different wave forms.

“The long term vision is this tool is going to be a regular part of our daily lives,” Garten told me. “You know, like pedometers that help people manage and understand their physical exercise. Brain health is going to be something that is on everybody’s mind. Up until now, there has been no way to, basically, like put a stethoscope up to your brain and say, ‘How is it doing?’”

Ten years ago, a NFT system with Muse-like capabilities (often found in a chiropractor’s office) would cost 5 figures and a closet-worth of space. Now the processing power lives on a standard smartphone, and Muse sensors cost $299.

Eventually, Garten predicted, doctors would actively use it to treat the mentally ill. Programmers would build brainwave-control apps for gaming and smart homes and surfing the Internet on top of Muse’s technology.

But for now it just gives you tweety birds.

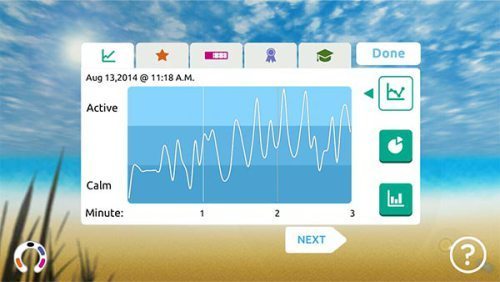

My porch session resulted in precisely zero of them:

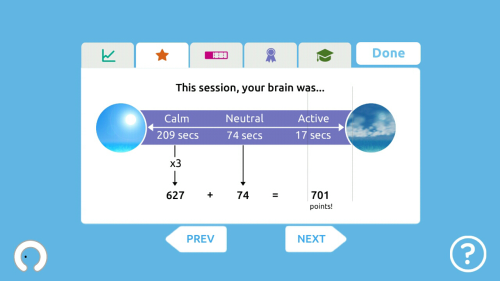

This session, for which I got a score of “31% calm,” would be the first of many mental workouts in my DYI NFT experiment. Would regular usage of the Muse headband actually change my brain and help fix my anxious life? Or would it turn out to be another wearable that’s more hype than help?

THE EXPERIMENT

The 2014 Muse headband

The hypothesis (aka sales pitch) was that by using Muse, I’d improve my ability to focus and maintain my cool during my stressful day-to-day.

So for fifteen days, I performed a five-minute Muse Calm session each morning within an hour of waking up and shaking off sleep. I’d sit in a similar setting (straight-back chair in a room alone), in similar clothing (comfortable, shorts and t-shirt, no shoes), with no distractions (accomplished via Bose noise-canceling earbuds) every time.

Additionally, I performed a series of sessions in various random non-comfortable settings, to test whether different mental exercises produced different results, or whether I could remain calm while being assaulted by various outside forces—which is the real goal of NFT, rather than simply getting better at a “game” in quiet isolation.

Though the app would tell me if my brain was getting better at calming itself during the exercise, the less easy-to-quantify result would be to see whether my level of general anxiety would decrease as I got better at the Calm app. (I.e. am I forming these alleged neural pathways?) Garten and Calm each told me that once I completed enough sessions (5,000 points’ worth), the app would unlock insights about how my brain was doing, which could shed some light on my meta-state. But I also tracked my overall emotional and mental state by keeping regular journal entries throughout the two weeks.

For a control—and as a basic BS test—I performed a session while reading a book instead of doing the breathing exercise. I read three pages of Murakami’s new one, Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki, and my brain was all sorts of active. Mr. Murakami, your work is stimulating. Science hath proven it:

THE RESULTS

Most of my morning sessions took place between 8 and 11 a.m. I keep a somewhat irregular sleep schedule (a source of anxiety, or symptom?), but aim for 7 hours a night. The important part for this experiment was to make sure that I did my Muse session within an hour of waking, but after I had stopped being groggy. In other words: before my morning exercise, after my morning pee.

I kept the morning schedule up with a few exceptions: on August 18, the Muse Calm app caused the headband to think my brainwaves had completely flatlined. I contacted the Muse team, and they confirmed that this was indeed a bug that they were working on fixing that day. On August 20, 22, 24, and 26 I skipped my morning session due to extenuating circumstances. (The 24th, for example, was my birthday, and I stayed out until 8 a.m.. My first session that day was at 4 p.m. and resulted in a hangover-level 31%.) But throughout my 15-day experiment, I never went a day without doing one or more sessions, and I never went two days without doing a standardized morning session.

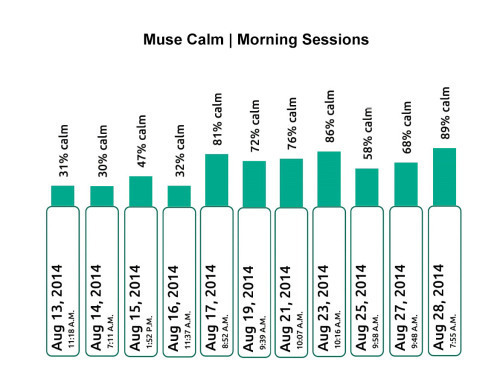

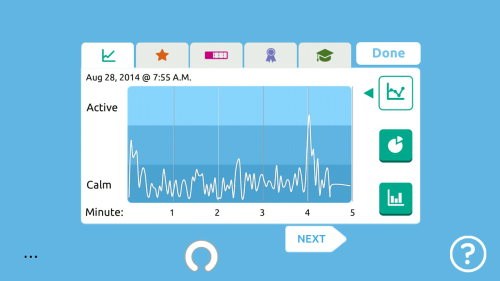

In all, I completed 24 sessions. Here’s how my morning sessions went over the course of the two weeks:

You’ll notice that I did pretty poorly for the first several sessions, then experienced a jump in improvement on August 17. What this chart doesn’t show is that though it was that August 17 was actually the seventh session I’d done in total. So I was getting better, but I’m not entirely sure why such a dramatic jump. You’ll also notice a slight dip on the 25th and 27th. On these days, I was having a couple of particularly anxious mornings (due to personal issues); however, on these days I still maintained double the calm as my first few sessions—which were less emotionally fraught than these days.

My final morning session of the experiment, on August 28, was a serene 89%—my best yet, and just one spike of brain activity away from monk-like zen:

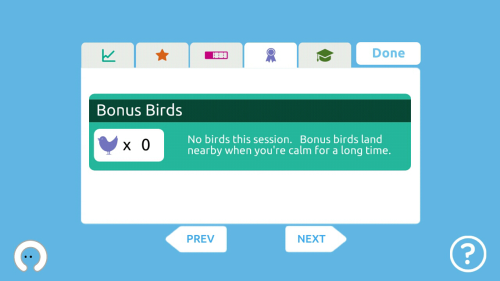

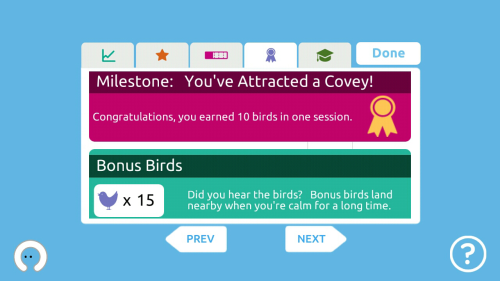

More importantly, I attracted a fucking flock of tweety birds:

Here’s how I performed on my random sessions in less-controlled environments:

Clearly, it was harder for me to focus and remain calm when I was tired or emotionally compromised.

Trains made it easier to focus (likely due to the lack of noise and abundance of leg room). Airplanes tend to give me claustrophobia, but it’s also likely that the vibrations of the plane itself caused my muscles to move (generating louder electrical signals than your brain emits) and made my results so poor during the flight. There certainly was a lot of shaking going on during my flight.

Interestingly, listening to calming music (I tend to put Blackmill’s “Miracle” album on repeat when I want to relax or single-task) outperformed no sound (simply trying to calm myself without an aid). On August 27, my regular session with the app’s wind and waves, resulted in 12% less calm than my music experiment immediately after.

As far as the meta, “how am I doing” portion of the experiment went, I eagerly awaited when I could unlock the “Insights About You” page of the app, after racking up enough “calm points”. Disappointingly, though Garten and Muse Calm both promised me these “additional features and special insights into my brain”, once I unlocked the screen, I got simply a blank, broken page:

When asked, the Muse publicist confirmed that the feature “actually hasn’t been developed yet” and relayed the (in my opinion) unlikely explanation that “there was a miscommunication between the product and dev teams.”

My journal entries indicated a general decrease in agitation and worry by the end of the experiment. My ability to focus on tasks (primarily writing) seemed to improve. I have a tendency to get distracted when I’m writing, and in the same way that the waves-and-wind exercise in the app teaches you to power through distractions and focus on your breath, I felt that I already was improving my ability to notice a distraction but keep it in the background instead of indulging it.

Furthermore, as I walked down busy streets or lay in bed—times when I normally would ruminate—I found myself subconsciously slowing breaths and counting them as a means of shoving out bad thoughts and calming down.

“Many smart people who use their brains a lot are ‘high beta,’” explained my therapist (whose name I’ll omit to maintain a shred of personal privacy) when I asked her about this. An award-winning Manhattan psychologist and author, she has used NFT herself. A few years ago, she used a professional-grade version of Muse to teach her own active brain to be silent. “I couldn’t go to sleep without the TV on,” she said. “The minute it was quiet, my brain would explode with activity.”

With measurement and some mental situps, she calmed her own rumination—as apparently thousands of people have done at clinics that use EEG therapy. That “neuroplasticity” thing that people throw around, it turns out, is real. And it works as fast as one can form a bad habit.

“The brain can be retrained,” she said. “People think it can’t, but it can.”

POTENTIAL ISSUES

One of the main limitations of the Muse Calm app—or at least questions that I had from the beginning—was the validity of the wind-and-waves feedback sound system itself, as well as the “count your breaths” mediation exercise. My assistant, Erin, who’s a yoga instructor and meditation expert by night, was skeptical that the Muse Calm exercise was the most effective method the app could have chosen. Why would you have the distracting sounds get worse when you were most compromised? she said. Doesn’t that create a self-defeating cycle?

Garten responded: “We did a bunch of experimentation on positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement and we ultimately built an application with a mix of both. The negative reinforcements of the wind can definitely be distracting, but what you learn over time is also this lesson in not being judgmental when things don’t work.”

A 2010 study by scientists from the University of Pennsylvania and Georgetown found positive links between “mindfulness training”—the popular meditation practice of calmly noticing, but not changing what’s happening to you—has a positive effect on working memory. The Muse Calm’s “notice and count your breaths” exercise is a form of mindfulness training, and appears to hold up under scientific scrutiny, but the wind-and-waves feedback loop (NFT) throws a bit of a wrench into true “mindfulness”, since the act of being mindful ends up affecting your environment, whereas the point of mindfulness meditation is to notice but not affect.

Could a “pure” mindfulness exercise without the instant and self-reinforcing feedback outperform Calm’s NFT/mindfulness hybrid? Beats me, but it’s a question I’d want to test in future experiments.

Other limitations or potential variables that could affect the science behind my two-week experiment include the following:

Factors such as the exact time I awoke and what kind of bed I slept in changed slightly from day to day, as I was traveling and couch-hopping. While the course of my experiment showed an upward trend in calm, I wasn’t able to duplicate the time and setting of each of my morning sessions precisely, which could affect the results to some degree.

Since I was dealing with the fresh personal trauma, perhaps I was naturally recovering psychologically during the two weeks of my experiment (i.e. regression to the mean). My therapist insists that the relationship wound was too fresh and two weeks is not enough time to work through anything, but it still could be a factor.

This experiment was only two weeks, which I was told would be a sufficient minimum for results. More time could certainly help verify the trends I observed in my short experiment. (And I plan to keep using Muse over the next few months to track just that.)

And of course, my observations about how I was feeling were, by nature, subjective. (However, if my psychological improvement is all in my head, that’s okay by me—it was in my head to begin with! And actually, I’ve interviewed one scientist who’s studying how placebos actually form neural pathways that can physically cure psychological issues. Very interesting stuff happening in this field.)

EPILOGUE

The electrodes had no problem beaming the signal from my sweaty head to my Android this time.

I was sitting on a set of red bleachers in disgusting New York humidity in the middle of Times Square, Manhattan. The familiar female voice in my headphones instructed me to close my eyes, as she had two dozen times before.

Around me, a trillion stressed-out tourists were busily taking selfies and worrying about pick pockets. A troupe of Chinese activists had just accosted me with pamphlets and signs concerning some “Jesuit Father discrimination” something-or-other, meanwhile a quartet of feather-headressed ladies performed a synchronized dance on the steps below me. A bumblefoot pigeon had taken up residence on my step and didn’t seem to want to leave me alone. My entire body was sweating.

I’d just walked through my old neighborhood, a surprisingly painful reminiscence. Unexpectedly, one of my ex’s favorite songs had begun playing on shuffle as I made my way through the crowd, further dampening my mood. In the back of my head were the several overdue stories for editors of various publications in line with my book launch, and the approximately 200 priority emails stacked up in my inbox. I was lugging my entire life in an overstuffed backpack and had just spilled protein drink all over my shorts—which I just now realized were my only available leggings, because I’d left the remaining two pairs of jeans I owned back in my friend Simon’s freezer (here’s why). I was pensive and hot and frustrated and dripping.

Once again, I donned my brainwave headband, which once again told me to breeaaathe.

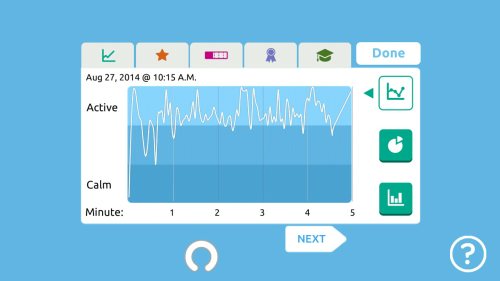

About halfway through my five-minute session—the twenty-fifth I’d undertaken since meeting Muse—some nearby tourists began singing “Happy Birthday” so loudly that I could hear them through my noise-canceling headphones. A fire engine blared its siren in place for a full minute, stuck one block away in Times Square traffic. My butt burned on the red steps, in the August heat. My posture was killing me.

At the end of five minutes, Muse confirmed: I was pretty damn calm.

The two spikes in active brain activity in this chart were the fire truck and the birthday party, each of which I recovered from almost instantly. Aside from that, my brain state was either neutral or calm the entire time:

Plus I attracted 15 tweety birds:

Despite the chaos in my life, there was no doubt that this little device had made me a calmer person in just two weeks. I could play through the mental and physical pain with twice the composure as just fifteen days before.

Muse has a way to go before the guy with the electric headband on in Times Square doesn’t just look like an idiot. And the Calm app could definitely use work. (Different meditation exercises, please?) However, the science behind what the Muse team is doing is real, the technology promising, and a bevy of independent programmers are already building fascinating applications on top of Muse.

With the development of cheap and portable EEG monitors like Muse, are we a few lines of code away from controlling light switches and video games with our brains? It’ll take a while.

But I, at least, am a step closer to mind over matter.

Breeeeathe….

###

Question of the day: What do you think are the next frontiers of self-experimentation and self-tracking? What would you like me to test for you? Please let me know in the comments by clicking here.

September 9, 2014

The Tim Ferriss Show: Interview with Peter Thiel, Billionaire Investor and Company Creator

“Freedom lies in being bold.” – Robert Frost

This episode’s guest is the incredible Peter Thiel.

Peter is a serial company founder (PayPal, Palantir), billionaire investor (first outside investor in Facebook, 100+ others), and author of the new book Zero to One. Whether you’re an investor, entrepreneur, or simply a free thinker aspiring to do great things, I highly recommend you grab a copy. His teachings on differentiation, value creation, and competition alone have helped me make some of the best investment decisions of my life (e.g. Twitter, Uber, Alibaba, etc.).

This podcast episode was experimental, as I was on medical leave. It includes both audio and written questions. What are Peter’s favorite books? Thoughts on tech and government, and more? Answers to these “bonus questions” can be found in the text below.

For the longer, main audio discussion, you can:

Listen to the episode on iTunes

Download it as an MP3 (right click “save as”): Here it is.

Or stream it now below (If you’re reading this in e-mail, please click here to stream):

Now, a bit more on Peter…

Peter Thiel has been involved with some of the most dynamic companies to emerge from Silicon Valley in the past decade, both as a founder and investor. Peter’s first start-up was PayPal, which he co-founded in 1998 and led to a $1.5 billion acquisition by eBay in 2002. After the eBay acquisition, Peter founded Clarium Capital Management, a global macro hedge fund. Peter also helped launch Palantir Technologies, an analytical software company which now books $1B in revenue per year, and he serves as the chairman of that company’s board. He was the first outside investor in Facebook, and he has invested in more than 100 startups total.

There are a lot of lessons in this podcast, even more in his new book, and below are a few follow-up questions that Peter answered via text.

Enjoy!

TIM: What is the book (or books) you’ve most often gifted to other people?

PETER: Books by René Girard, definitely — both because he’s the one writer who has influenced me the most and because many people haven’t heard of him.

Girard gives a sweeping view of the whole human experience on this planet — something captured in the title of his masterwork, Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World — but it’s not just an academic philosophy. Once you learn about it, his view of imitation as the root of behavior is something you will see every day, not just in people around you but in yourself.

What is your favorite movie or documentary?

PETER: No Country for Old Men — a movie about whether all events are simply random, but also a work in which no detail is left to chance. I catch something new every time I watch it.

To increase technological growth/progress, what are the key things you think the government or people should do for greatest impact?

PETER: Libertarians like to call out excessive regulations, and I think they’re right.

But it’s a vicious circle: when governments make it harder to get things done, people come to expect less; when expectations are low, technologists are less likely to aim high with the kind of risky new ventures that could deliver major progress. The most fundamental thing we need to do is regain our sense of ambition and possibility.

For those who want to improve their ability to question assumptions or commonly held “truths,” which philosophers, or reading, or exercises, or activities might you suggest?

PETER: It’s a great exercise to revisit predictions about the future that were made in the past.

People write a lot of history, and they make a lot of predictions, and I consume a lot of both. But it’s rare that people go and check old predictions. It’s a way to see — with the benefit of hindsight — the assumptions that people didn’t even know they were making, and that can make you more sensitive to the questionable conventions that surround us today. For example, The American Challenge by Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber argued in 1968 that Europe would be eclipsed by relentless American progress. But that progress never came. It’s instructive to go back and see why Servan-Schreiber was optimistic.

###

Now, some questions for you all…

Who should I interview next? Please let me know in the comments by clicking here.

Do you enjoy this podcast? If so, please leave a short review here. Help me get to 1,000! It’s so close!

Subscribe to The Tim Ferriss Show on iTunes.

Non-iTunes RSS feed

August 29, 2014

The Tim Ferriss Show: Interview of Kevin Kelly, Co-Founder of WIRED, Polymath, Most Interesting Man In The World?

This single interview — one of my favorites of all-time — was recorded in three short parts. You can:

Listen to all three on iTunes

Download them as MP3s (right click “save as”): Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

Or stream them now below (If you’re reading this in e-mail, please click here to stream):

This podcast is brought to you by The Tim Ferriss Book Club, which features a handful of books that have changed my life. Here’s the list. You can also find all 20+ episodes of this podcast here. Some are sober and some are drunk, but the guests are all great.

Now, on to this episode’s guest…

Kevin Kelly might be the real-life Most Interesting Man In The World.

He is Senior Maverick at Wired magazine, which he co-founded in 1993. He also co-founded the All Species Foundation, a non-profit aimed at cataloging and identifying every living species on earth. In his spare time, he writes bestselling books, co-founded the Rosetta Project, which is building an archive of ALL documented human languages, and serves on the board of the Long Now Foundation. As part of the last, he’s investigating how to revive and restore endangered or extinct species, including the Wooly Mammoth.

This episode touches on a lot of cool stuff. SERIOUSLY, A LOT.

Just scroll below and your head might explode. Tons of amazing links and goodies…

Enjoy!

Who should I interview next? Please let me know in the comments by clicking here.

Do you enjoy this podcast? If so, please leave a short review here. It keeps me going…

Subscribe to The Tim Ferriss Show on iTunes.

Non-iTunes RSS feed

Show Notes and Select Links from the Episode

Kevin Kelly’s biggest regret

His lesson in finding contentment in minimalism and “volunteer simplicity”

How he realized that writing actually creates ideas

Why he promised himself that he would never resort to teaching English while traveling abroad

The “creator’s dilemma,” or how you have to go lower to get higher

Why you don’t want to be a billionaire

His realizations after doing a “6 months until death” challenge

His Kickstarter-funded project linking angels and robots

Why a self-proclaimed ex-hippie waited until his 50th birthday to try LSD for the first time

Why a population implosion is probable in the next 100 years

The greatest gift you can give to your child

The criteria for Amish technology assimilation

What technology-free sabbaticals can do for you

Long Now Foundation’s vision of a better civilization

The graphic novel for young people on how to become indispensable

His favorite fiction book

The great resource Kevin compiled for documentary lovers

How he accumulated enough books to fill a two-story library

Mythbuster’s Adam Savage’s organizational method, which transformed Kevin’s life

The project that everyone should undertake at least once in life

The advice he would give to his younger self

LINKS FROM THE EPISODE

Visit the Tim Ferriss Book Club to find a new book each month (or so) that’s changed my life

Wired Magazine

Learn more about the All Species Foundation

The Rosetta Project

Long Now Foundation

Get more information about 1,000 True Fans

Learn more about Voluntary Simplicity

This American Life, Episode 50 with Kevin Kelly

Tim Ferriss Show Episode 2: Interview with Josh Waitzkin

True Films – Kevin Kelly’s site about documentaries

Learn more about sodium valproate

www.Uline.com – shipping, industrial, and packing materials

Adam Savage – host of Mythbusters

Elance – resource for hiring freelancers

Whole Earth Catalog

KK.org – Kevin Kelly’s website

Books Mentioned in the Episode

Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut

Vagabonding: An Uncommon Guide to the Art of Long-Term World Travel by Rolf Potts

Cool Tools: A Catalog of Possibilities by Kevin Kelly

What Technology Wants by Kevin Kelly

The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide by Kevin Kelly

The Adventures of Johnny Bunko by Daniel H. Pink

So Good They Can’t Ignore You by Cal Newport

Shantaram: A Novel by Gregory David Roberts

Searching for Bobby Fischer: The Father of a Prodigy Observes the World of Chess by Fred Waitzkin

True Films by Kevin Kelly

Documentaries Mentioned in the Episode

Man on Wire

King of Kong

State of Mind

August 25, 2014

The Art of Strategic Laziness

David Heinemeier Hansson (“DHH”)

The following is a guest post by Shane Snow, a frequent contributor to Wired and Fast Company. Last year, he wrote about his two-week Soylent experiment, which went viral and racked up 500+ comments.

This post is adapted from his new book, SMARTCUTS, and it will teach you a few things:

How to use strategic “laziness” to dramatically accelerate progress

How “DHH” became a world-class car racer in record time, and how he revolutionized programming (they’re related)

A basic intro to computer programming abstraction

Note: the technical aspects of programming have been simplified for a lay audience. If you’d like to point out clarifications or subtleties, please share your thoughts in the comments! I’d love to read them, as I’m thinking of experimenting with programming soon.

Enter Shane Snow

The team was in third place by the time David Heinemeier Hansson leapt into the cockpit of the black-and-pink Le Mans Prototype 2 and accelerated to 120 miles per hour. A dozen drivers jostled for position at his tail. The lead car was pulling away from the pack—a full lap ahead.

This was the 6 Hours of Silverstone, a six-hour timed race held each year in Northamptonshire, UK, part of the World Endurance Championship. Heinemeier Hansson’s team, Oak Racing, hoped to place well enough here to keep them competitive in the standings for the upcoming 24 Hours of Le Mans, the Tour de France of automobile racing.

Heinemeier Hansson was the least experienced driver among his teammates, but the Oak team had placed a third of this important race in his hands.

Determined to close the gap left by his teammate, Heinemeier Hansson put pedal to floor, hugging the curves of the 3.7-mile track that would be his singular focus for the next two hours. But as three g’s of acceleration slammed into his body, he began to slide around the open cockpit. Left, then right, then left. Something was wrong with his seat.

In endurance racing, a first place car can win a six- or 12-hour race by five seconds or less. Winning comes down to two factors: the equipment and the driver. However, rules are established to ensure that every car is relatively matched, which means outcomes are determined almost entirely by the drivers’ ability to focus and optimize thousands of tiny decisions.

Shifting attention from the road to, say, a maladjusted driver’s seat for even a second could give another car the opportunity to pass. But at 120 miles per hour, a wrong move might mean worse than losing the trophy. As Heinemeier Hansson put it, “Either you think about the task at hand or you die.”

Turn by turn, he fought centrifugal force, attempting to keep from flying out while creeping up on the ADR-Delta car in front of him.

And then it started to rain…

***

When Heinemeier Hansson walked onto the racing scene in his early 30s, he was a virtual unknown, both older and less experienced than almost anyone in the leagues. A native of Denmark, he’s tall, with a defined jaw and dark spikey hair. At the time he raced 6 Hours of Silverstone, it had been about five years since he first drove any car at all.

That makes him one of the fastest risers in championship racing.

Despite that, Heinemeier Hansson is far better known among computer programmers—where he goes by the moniker DHH— than car enthusiasts. Though most of his fellow racers don’t know it, he’s indirectly responsible for the development of Twitter. And Hulu and Airbnb. And a host of other transformative technologies for which he receives no royalties. His work has contributed to revolutions, and lowered the barrier for thousands of tech companies to launch products.

All because David Heinemeier Hansson hates to do work he doesn’t have to do.

DHH lives and works by a philosophy that helps him do dramatically more with his time and effort. It’s a principle that’s fueled his underdog climbs in both racing and programming, and just might deliver a win for him as the cars slide around the rainslicked Silverstone course.

But to understand his smartcut, we must first learn a little bit about how computers work.

Think of the way a stretch of grass becomes a road. At first, the stretch is bumpy and difficult to drive over. A crew comes along and flattens the surface, making it easier to navigate. Then, someone pours gravel. Then tar. Then a layer of asphalt. A steamroller smooths it; someone paints lines. The final surface is something an automobile can traverse quickly. Gravel stabilizes, tar solidifies, asphalt reinforces, and now we don’t need to build our cars to drive over bumpy grass. And we can get from Philadelphia to Chicago in a single day.

That’s what computer programming is like. Like a highway, computers are layers on layers of code that make them increasingly easy to use. Computer scientists call this abstraction.

A microchip—the brain of a computer, if you will—is made of millions of little transistors, each of whose job is to turn on or off, either letting electricity flow or not. Like tiny light switches, a bunch of transistors in a computer might combine to say, “add these two numbers,” or “make this part of the screen glow.”

In the early days, scientists built giant boards of transistors, and manually switched them on and off as they experimented with making computers do interesting things. It was hard work (and one of the reasons early computers were enormous).

Eventually, scientists got sick of flipping switches and poured a layer of virtual gravel that let them control the transistors by typing in 1s and 0s. 1 meant “on” and 0 meant “off.” This abstracted the scientists from the physical switches. They called the 1s and 0s machine language.

Still, the work was agonizing. It took lots of 1s and 0s to do just about anything. And strings of numbers are really hard to stare at for hours. So, scientists created another abstraction layer, one that could translate more scrutable instructions into a lot of 1s and 0s.

This was called assembly language and it made it possible that a machine language instruction that looks like this:

10110000 01100001

could be written more like this:

MOV AL, 61h

which looks a little less robotic. Scientists could write this code more easily.

Though if you’re like me, it still doesn’t look fun. Soon, scientists engineered more layers, including a popular language called C, on top of assembly language, so they could type in instructions like this:

printf(“Hello World”);

C translates that into assembly language, which translates into 1s and 0s, which translates into little transistors popping open and closed, which eventually turn on little dots on a computer screen to display the words, “Hello World.”

With abstraction, scientists built layers of road which made computer travel faster. It made the act of using computers faster. And new generations of computer programmers didn’t need to be actual scientists. They could use high-level language to make computers do interesting things.

When you fire up a computer, open up a web browser, and buy a copy of my book online for a friend (please do!), you’re working within a program, a layer that translates your actions into code that another layer, called an operating system (like Windows or Linux or MacOS), can interpret. That operating system is a probably built on something like C, which translates to Assembly, which translates to machine language (1s and 0s), which flips on and off a gaggle of transistors.

(Phew.)

So, why am I telling you this? In the same way that driving on pavement makes a road trip faster, and layers of code let you work on a computer faster, hackers like DHH find and build layers of abstraction in business and life that allows them to multiply their effort.

I call these layers platforms.

***

At college in the early aughts, DHH was bored. Not that he couldn’t handle school intellectually. He just didn’t find very much of it useful.

He practiced the art of selective slacking. “Some of my proudest grades were my lowest grades,” he tells me.

We all know people in school and work with a masterful ability to maintain the status quo (John Bender on The Breakfast Club or the bald, coffee-swilling coworker from Dilbert), but there’s a difference between treading water and methodically searching for the least wasteful way to learn something or level up, which is what DHH did.

“My whole thing was, if I can put in 5 percent of the effort of somebody getting an A, and I can get a C minus, that’s amazing,” he explains. “It’s certainly good enough, right? [Then] I can take the other 95 percent of the time and invest it in something I really care about.”

DHH used this concept to breeze through the classes that bored him, so he could double his effort on things that mattered to him, like learning to build websites. With the time saved, he wrote code on the side.

One day, a small American web-design agency called 37signals asked DHH to build a project management tool to help organize its work. Hoping to save some time on this new project, he decided to try a relatively new programming language called Ruby, developed by a guy in Japan who liked simplicity. DHH started coding in earnest.

Despite several layers of abstraction, Ruby (and all other code languages) forces programmers to make countless unimportant decisions. What do you name your databases? How do you want to configure your server? Those little things added up. And many programs required repetitive coding of the same basic components every time.

That didn’t jibe with DHH’s selective slacking habit. “I hate repeating myself.” He almost spits on me when he says it.

But conventional coders considered such repetition a rite of passage, a barrier to entry for newbies who hadn’t paid their dues in programming. “A lot of programmers took pride in the Protestant work ethic, like it has to be hard otherwise it’s not right,” DHH says.

He thought that was stupid. “I could do a lot of other interesting things with my life,” he decided. “So if programming has to be it, it has to be awesome.”

So DHH built a layer on top of Ruby to automate all the repetitive tasks and arbitrary decisions he didn’t want taking up his time. (It didn’t really matter what he named his databases.) His new layer on top of programming’s pavement became a set of railroad tracks that made creating a Ruby application faster. He called it Ruby on Rails.

Rails helped DHH build his project—which 37signals named Basecamp—faster than he could have otherwise. But he wasn’t prepared for what happened next.

When he shared Ruby on Rails on the Internet, programmers fell in love with it. Rails was easier than regular programming, but just as powerful, so amateurs downloaded it by the thousands. Veteran coders murmured about “real programming,” but many made the switch because Rails allowed them to build their projects faster.

The mentality behind Rails caught on. People started building add-ons, so that others wouldn’t have to reinvent the process of coding common things like website sign-up forms or search tools. They called these gems and shared them around. Each contribution saved the next programmer work.

Suddenly, people were using Ruby on Rails to solve all sorts of problems they hadn’t previously tackled with programming. A toilet company in Minnesota revamped its accounting system with it. A couple in New Jersey built a social network for yarn enthusiasts. Rails was so nice that more people became programmers.

In 2006 a couple of guys at a podcasting startup had an idea for a side project. With Rails, they were able to build it in a few days—as an experiment—while running their business. They launched it to see what would happen. By spring 2007 the app had gotten popular enough that the team sold off the old company to pursue the side project full time. It was called Twitter.

A traditional software company might have built Twitter on a lower layer like C and taken months or years to polish it before even knowing if people would use it. Twitter—and many other successful companies—used the Rails platform to launch and validate a business idea in days. Rails translated what Twitter’s programmers wanted to tell all those computer transistors to do—with relatively little effort. And that allowed them to build a company fast. In the world of high tech—like in racing—a tiny time advantage can mean the difference between winning and getting passed.

Isaac Newton attributed his success as a scientist to “standing on the shoulders of giants”—building off of the work of great thinkers before him.

Platforms are tools and environments that let us do just that. It’s clear how using platforms applies in computer programming, but what if we wanted to apply platform thinking to something outside of tech startups?

Say, driving race cars?

***

David Heinemeier Hansson was in a deep hole. Halfway through his stint, the sprinkling rain had become a downpour. Curve after curve, he fishtailed at high speed, still in third place, pack of hungry competitors at his rear bumper.

LMP cars run on slick tires—with no tread—for speed. The maximum surface area of the tire is gripping the road at any moment. But there’s a reason street vehicles have grooves in them. Water on the road will send a slick tire drifting, as the smooth rubber can’t channel it away. Grooved tires push water between the tread, giving some rubber grip and preventing hydroplaning. The slicker the tires—and the faster the speed—the more likely a little water will cause a car to drift.

That’s exactly what was happening to the LMP racers. As the rain worsened, DHH found himself sliding around the inside of a car that was sliding all over the race track. Nearby, one driver lost grip, slamming into the wall.

Cars darted for the pits at the side of the track, so their teams could tear off the slick tires and attach rain tires. Rain tires are safer, but slower. And they take a precious 13-plus seconds to install. By the time the car has driven into the pits, stopped, replaced the tires, and started moving again, more than a minute can be lost.

DHH screamed into his radio to his engineer, Should I pit in for new tires?

Like I said, DHH wasn’t the most experienced racer. He had gotten into this race because he was skilled at hacking the ladder. A few years into 37signals’s success, and with Rails taking a life of its own, Hansson had started racing GT4—essentially souped-up street cars—in his spare time.