Christopher Priest's Blog, page 14

May 25, 2013

Sometimes I get out a bit

As part of the annual Charing Cross Road Fest, my new novel The Adjacent will be launched at Blackwell’s Bookshop (100 Charing Cross Road) on Saturday 22nd June. I will be in conversation with Simon Ings, from 12:30 lunchtime. Tickets are free, but have to be booked in advance.

As part of the annual Charing Cross Road Fest, my new novel The Adjacent will be launched at Blackwell’s Bookshop (100 Charing Cross Road) on Saturday 22nd June. I will be in conversation with Simon Ings, from 12:30 lunchtime. Tickets are free, but have to be booked in advance.

Simon is the editor of Arc, the digital magazine about the future, and is the author of Dead Water, one of the novels inexplicably neglected by last year’s Clarke Award judges. He is currently writing a science fiction novel about Hampshire, a place he hates. His other books are soon to be reissued by Gollancz.

Click here for full details of the Blackwell’s event. (For “Afghanistan” read “Anatolia”, incidentally. Not my error, and not Blackwell’s, either.) Tickets can be ordered from: [email protected]

Be there?

While I am on this sort of subject, two weeks earlier, on Saturday 8th June, I will be addressing the British Humanist Association annual conference, at the Hilton Leeds City Hotel, Neville Street, in Leeds. As this is a conference you would have to join in advance – places are still available, and may be booked here.

May 14, 2013

SELECTIVE INDEX — May 2013

Here are links to some recent blog entries on this site:

12 May 2013

Bomber Command memorial – the most recent entry.

‘In June 2012 a permanent memorial was created to the RAF Bomber Command campaign of the second world war. The memorial is to all lives lost during the war, notably the estimated 600,000 civilians and non-combatants killed on the ground by the bombing, but it is also, at last, a memorial to the young men, all volunteers, who served as aircrew in the air force. Theirs was one of the most dangerous jobs of the war.’

16 December 2012

Lionel Asbo by Martin Amis – a review of this novel.

‘Bad books are usually written by incompetents, so are bad in uninteresting ways, but occasionally a real corker comes along: a poor or careless or contemptible piece of work by a highly rated author.’

9 December 2012

Robert McCrum: “cockroach in the world of books” – a response to one of McCrum’s Guardian essays.

‘McCrum’s weakness is that he will not acknowledge his blind spots. Genre fiction, or what he thinks is genre fiction, is the prime example. He abdicates himself from addressing the problem by assuming that genre fiction abides by rules and conventions that general fiction does not, and that it has an orthodoxy he neither understands nor wishes to learn about. He thinks it is a specialist form that can only be dealt with by an editor with specialist expertise.’

27 October 2012

Communion Town by Sam Thompson – one of the best novels of 2012.

‘This is not a review of a novel so much as a recommendation of one – the best new novel I have read this year is Sam Thompson’s Communion Town. It is a first novel of impressive skill and imaginative flair, ambitiously structured and beautifully written, described by the publisher as a city in ten chapters, which in fact sums it up admirably. The central city, which might be London, or Boston, or Tel Aviv, or Melbourne, grows slowly into vivid life as you read the stories of the various people who live there.’

28 March 2012

Hull 0, Scunthorpe 3 – a polemical essay about the ineptly managed 2012 Clarke Award shortlist.

‘It seems to me that 2011 was a poor year for science fiction. Of the sixty books submitted by publishers, only a tiny handful were suitable for awards. The brutal reality is that there were fewer than the six needed for the Clarke shortlist.’

2 January 2012

The Inner Man – The Life of J. G. Ballard by John Baxter – a review of this unreliable biography of the great writer.

‘Gossip is the main weakness of Baxter’s book, because he falls foul of the temptation to rely too heavily on the memories of living witnesses. From evidence I have seen elsewhere, much of this book appears to have been heavily influenced by long interviews with Michael Moorcock.’

May 12, 2013

At last, Dad! At last!

We are now only a few weeks away from the release of my next novel The Adjacent (to be published by Gollancz on 20th June), so it’s time to mention a debt. The background for a section of the book came from the RAF bombing campaign against Germany in the Second World War. This is the second of my novels to deal with this difficult period of British history: The Separation (2002) described more directly the impact on the life of a young man who flew with Bomber Command in the early part of the war. The Adjacent does not go over similar ground, but it does touch on the same sensitive subject.

In June 2012 a permanent memorial was created to the RAF Bomber Command campaign of the second world war. The memorial is to all lives lost during the war, notably the estimated 600,000 civilians and non-combatants killed on the ground by the bombing, but it is also, at last, a memorial to the young men, all volunteers, who served as aircrew in the air force. Theirs was one of the most dangerous jobs of the war. 55,573 RAF men were killed in bombing raids during the war, and another 18,000 were wounded or taken prisoner – which was more than half the total number of crew involved (about 120,000). Serving in an RAF bomber gave a worse chance of non-survival than that of an infantry officer in the 1914-18 war. Bomber Command survivors and the families of many of the lost men have campaigned for years for the sacrifice of so many lives to be acknowledged.

In June 2012 a permanent memorial was created to the RAF Bomber Command campaign of the second world war. The memorial is to all lives lost during the war, notably the estimated 600,000 civilians and non-combatants killed on the ground by the bombing, but it is also, at last, a memorial to the young men, all volunteers, who served as aircrew in the air force. Theirs was one of the most dangerous jobs of the war. 55,573 RAF men were killed in bombing raids during the war, and another 18,000 were wounded or taken prisoner – which was more than half the total number of crew involved (about 120,000). Serving in an RAF bomber gave a worse chance of non-survival than that of an infantry officer in the 1914-18 war. Bomber Command survivors and the families of many of the lost men have campaigned for years for the sacrifice of so many lives to be acknowledged.  Winston Churchill, who through much of the war was an enthusiastic advocate of destroying German cities, and killing as many civilians as possible, changed his mind towards the end of the war, probably realizing belatedly how history might regard him. Under his orders, no Bomber Command campaign medal was ever struck, surviving career officers were demoted to their pre-war ranks, and most of the remaining civilian volunteers were demobilized and sent home as soon as possible.

Winston Churchill, who through much of the war was an enthusiastic advocate of destroying German cities, and killing as many civilians as possible, changed his mind towards the end of the war, probably realizing belatedly how history might regard him. Under his orders, no Bomber Command campaign medal was ever struck, surviving career officers were demoted to their pre-war ranks, and most of the remaining civilian volunteers were demobilized and sent home as soon as possible.

The  memorial is situated in Green Park, London, at the Hyde Park Corner end of Piccadilly. It contains some suitable statuary of an RAF crew, and several commemorative tablets explaining what was at stake for the ordinary people who were so terribly affected by this aspect of the war. I found it to be an unpretentious monument, and was moved by the many simple and heartfelt comments people had written on their cards and tributes.

memorial is situated in Green Park, London, at the Hyde Park Corner end of Piccadilly. It contains some suitable statuary of an RAF crew, and several commemorative tablets explaining what was at stake for the ordinary people who were so terribly affected by this aspect of the war. I found it to be an unpretentious monument, and was moved by the many simple and heartfelt comments people had written on their cards and tributes.

Because none of my family or close friends were involved in RAF activities during WW2, and because I am a novelist and not an historian, I’ve always felt a bit uncomfortable with the idea of my taking a stand on the morality or otherwise of the bombing of Germany. However, I have been reading books about this subject ever since I was a teenager, invariably torn between horror of what happened and sympathy for those caught up in it.

I have long held that many of the books written by participants in WW2 are the literary equivalent of the outpouring of poetry that appeared in the First World War. In fact, relatively little good poetry was produced in 1939-45 (Daniel Swift’s recent book Bomber County, 2010, is the best existing account of what we have — reviewed by me here), but in the immediate postwar years, starting in the late 1940s but mostly from about 1950 onwards, there was a veritable flood of books containing war stories, war memoirs, war experiences: captives escaping from prisoner-of-war camps, agents parachuted behind enemy lines, bombers attacking dams in the Ruhr, nurses and firemen in the Blitz, gunners in the rear turret of Lancaster bombers, U-boat submariners in the North Atlantic, memoirs of generals, and so on. At first, during the 1950s, these books were produced by trade publishers as general titles, but in recent years those that are reprinted come from specialist military publishers, small presses or have been sponsored by the families. Many can be found in the Military History sections of large bookstores (which like many bookshop departments can be a bit of a misleading label), and of course the internet will locate most of them. They make up a neglected but unique vernacular history of that appalling war. None of them is a literary masterpiece, but like much of the poetry from the earlier war they are written with energy and a sense of total personal experience and commitment, they are moving, they contain material that is sometimes graphic or shocking or surprising, they are above all true in every sense of the word. Here are a few, but there are literally hundreds more:

Bomber Pilot, Leonard Cheshire (1943)

The Wooden Horse, Eric Williams (1949)

A WAAF in Bomber Command, Pip Beck (1989)

No Moon Tonight, Don Charlwood (1956)

The Naked Island, Russell Braddon (1952)

P.Q.17, Godfrey Winn (1947)

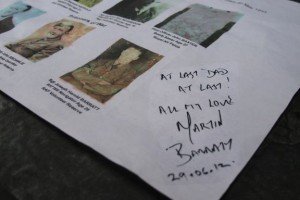

A postscript. I visited the Bomber Command memorial at the end of June 2012, just two days after it had been officially opened by the Queen. Many of the floral tributes and cards were still fresh. I found the one from Martin Barratt (in the photograph above, dated the day before), and took a couple of pictures of it. The poignant little message struck me as sharing the same sense of ordinary decency and pain that I had encountered many times before in these books. I moved away, looking at the other tributes. When I returned to the place where Mr Barratt’s message had been left, I discovered that it was now missing. It had not been moved to one side, it had not fallen to the floor, there was not enough of a wind to have blown it away. I looked everywhere around, but someone must have removed it. I can’t imagine why.

April 3, 2013

The Explorer by James Smythe — Harper Voyager, 2013, £12.99, 265pp, ISBN 978-0-00-745675-8

The Explorer is the second of James Smythe’s novels to be released within a few months. This UK publication is datelined 2013 although it is copyrighted 2012, perhaps from an earlier US edition. Could this be a first novel, or would that be The Testimony, released a while earlier? The instinct is of course to go critically a bit easier on a first novel, so just in case …

First impressions are good. Smythe is young, he writes good clean prose, he is obviously serious in intent (and therefore we might assume he is ambitious as a writer, ambitious in a greater sense than just becoming a best-selling or highly paid author, but maybe those too), and at a time when many young authors are coming into the field of fantastic literature equipped with not much more than a love of fantasy epics or Doctor Who, he seems to be well versed in the various tropes of serious science fiction.

The story of The Explorer is simply described: a spacecraft is launched from Earth bearing six astronauts. Within a few days of the launch the crew members start dying, and soon only one remains alive: a young journalist called Cormac Easton. Cormac is unable to steer or control the craft, so he is trapped inside while it continues with its programmed mission: to go further into deep space than any manned craft has gone before. Gradually the spaceship runs out of fuel and supplies until it is inevitable that Cormac will not escape with his life. Before the craft becomes completely unusable he activates some kind of auto-destruct system, and he and it are destroyed. This happens before the end of page 52. More than 200 pages of novel remain. What then follows I will leave to Smythe to relate as it is where the book becomes unusual and intriguing.

The story of The Explorer is simply described: a spacecraft is launched from Earth bearing six astronauts. Within a few days of the launch the crew members start dying, and soon only one remains alive: a young journalist called Cormac Easton. Cormac is unable to steer or control the craft, so he is trapped inside while it continues with its programmed mission: to go further into deep space than any manned craft has gone before. Gradually the spaceship runs out of fuel and supplies until it is inevitable that Cormac will not escape with his life. Before the craft becomes completely unusable he activates some kind of auto-destruct system, and he and it are destroyed. This happens before the end of page 52. More than 200 pages of novel remain. What then follows I will leave to Smythe to relate as it is where the book becomes unusual and intriguing.

Stop reading here if you believe that first novelists (or even second novelists) should have their attempts rubber-stamped with routine approval. It’s also a good place to stop reading as the partial plot synopsis in the previous paragraph might well make you curious about what happens next. I certainly was curious, and in fact Smythe keeps the mystery going almost until the very end. I don’t want this blog review to make people think, even for a moment, that this is not a book worth reading. The uncommon quality of its plot makes it a novel that stands out from the rest, and certain details and anomalies add to that.

The novel has many such anomalies, some of them minor. The spaceship, for example, is called the Ishiguro, named after a Japanese scientist called Hidemori Ishiguro who designed the ship’s engine. Ishiguro is a fairly common Japanese name, so that’s OK. But it’s also the name of Kazuo Ishiguro, a well-known Japanese-born novelist who has already shown a more than passing interest in novels based on speculative ideas. The use of his surname here leapt out at me and it made me wonder if it was some kind of metaphysical cross-reference, a hint that the author was writing about something more than a straightforward journey into space. Maybe that’s just a detail.

But a larger anomaly, larger because it continues throughout the novel, is created by all manner of practical descriptions and accounts of the lives of the astronauts and the spacecraft itself. I was unconvinced by the astronauts themselves, simply because they behave like no other astronauts I have ever heard of or seen in action on television. The one thing everyone knows about astronauts (and Smythe knows it too, because he describes it) is that they go through years of selection, preparation and training, and detailed physical, mental and psychological testing. Even if all their personal idiosyncrasies are not entirely ironed out or controlled before the launch, the training imposes a high standard of teamwork and practical precision. The five or six allegedly trained and tested astronauts in The Explorer go to pieces within a few days of the start of the mission: a couple of them are shagging in a spare storeroom, they call one of the women astronauts “Dogsbody”, they bicker and argue about trivial matters, and soon they start dying in mysterious circumstances.

As for the spaceship itself, it is described as having bags of unused space (including the spare storeroom), seems clean and tidy for most of the time, but above all has a double-skinned hull. This design feature seems to have more relevance to the needs of the plot than to the operation of the craft, because it becomes essential as a long-term hiding place. I was sometimes reminded, uncomfortably, of the similar narrative device in Flowers in the Attic – not a comparison a good writer like Smythe will welcome. This double skin is apparently sufficiently wide for someone to move around in, and contains enough air, heating and, I think, plumbing for a man to occupy the area for weeks on end. Secret viewing hatches are everywhere, and these enable the story to continue. It is all too contrived for comfort.

Then we find that the craft is capable of “stopping” in space more or less at the throw of a switch, and as soon as it stops the “gravity” comes back on. When the engine is turned on again, the occupants of the spaceship immediately suffer the conditions of free fall. (Surely this, or something like it, would be more likely to work the other way round?) Astronauts carrying out maintenance or repairs during any of these “stops” have to don spacesuits and carry out space walks – throughout these EVAs they continue to argue about personal matters and disagreements, and when they do get down to perform the tasks for which they have left the spacecraft most of their work is to sort out a mass of wiring contained behind an access plate, a bit like telephone engineers repairing crossed lines in a terminal on the side of a suburban street.

None of this (or a lot of other stuff like it) convinced me on any logical or practical level, and I say this from the point of view of someone who does not have much grasp of technological or space-science procedures. But the overall falseness of the set-up, taken together with my much more instinctively dependable doubts about the behaviour of the characters, had the promising effect of making me wonder what the author might really be up to.

The text quickly starts showing evidence of these irregularities, and so I began musing about the whole thing being somehow in quotation marks, perhaps a dream or the ravings of a madman, or a description of a real-time simulation being carried out in a closed hangar somewhere in the Nevada desert, or maybe even a reality TV show. Something more than the events being described seemed to be going on. These totally implausible astronauts, flying in a spaceship like something out of Dan Dare, on a mission which appears to have no scientific or exploratory purpose at all, could not really be doing what the author insists they are doing. Could they? There must be another layer to all this nonsense. My interest was therefore held, and continued to be held for most of the rest of the novel.

Without giving too much away, because the plot of The Explorer develops in genuinely unexpected ways, the most serious weakness in the novel is the description of the characters, not just as astronauts but as people. We learn hardly anything at all about them in the first 52 pages, so that in the following sequence, the major part of the novel, the new and significant information we are given about them does not carry much surprise or interest. Smythe is experimenting with narrative unreliability here, which I find interesting, but that is a literary technique which is really only effective when the unreliable text seems convincing and thus memorable before it transpires that the author has not admitted everything relevant. For instance, the belated news of a pre-mission relationship between Cormac and one of the female astronauts emerges as additional information, not a revelation of any kind. This is because the woman herself barely comes to life whenever she is mentioned or takes a part in the action. By the time she is promoted by the author to being a major character, we are left wondering why she was so wan and bland before. The same is true in a similar way when we learn about the reality of Cormac’s marriage – not all is what it had appeared to be at first. The two male astronauts, named Quinn and Guy, are more or less indistinguishable from each other (in the way Cormac reacts to them, and because of the equal narrative weight the author gives them), even though one of them is mad and gay and German, while the other is not. Characterization is the key to all good writing but because Smythe has his attention elsewhere for most of the book, his ambitious and clever plot is significantly undermined.

These negative comments are directed to the author, should he come across them, and are intended in a constructive way. There is a lot to like in The Explorer, and I wanted to celebrate it more. James Smythe is obviously an intelligent writer, talented and seriously intended, and I look forward to whatever he comes up with next. I gather he is writing a sequel to The Explorer, news which, from the perspective of having just finished the first book, makes me wonder yet again if some numinous endeavour is going on. Some greater or more universal reality might be at hand.

To the reader I say: set aside the reservations I have expressed and read The Explorer with an open and welcoming mind. It is different in tone, subject-matter and ambition from almost any other SF novel you might read this year. No giant moles, artful coppers or talking horses here …

March 8, 2013

Sizing Up Books

With writers almost universally using computers, books have been getting longer and longer. When I began publishing in the 1970s, a full-length novel was usually between 70,000 and 80,000 words, but shorter novels often appeared. During that period word-length was often an issue with publishers, or at least it was in my experience, with pressure brought to bear to make books shorter. For instance, when I delivered my fourth novel, The Space Machine, which I now know was about 120,000 words, my publishers in both the UK and the USA demanded I cut it down by about a third, mainly to save themselves some of the cost of production. The American publisher even went to the trouble of commissioning an outside editor to read my allegedly long-winded manuscript and suggest ways of cutting it down to size. I wondered at the time if the editor’s fee was going to be larger or smaller than the saving they were hoping to make – in the event it was academic, because after I had read his suggestions I declined gently and of course politely.

The UK publisher, Faber, suggested some editorial amendments to the opening chapters. While I was looking at these suggestions, and because I am helpful by nature, I took the opportunity to make a few silent excisions as well, harmless to the story or characters. These cuts overall reduced the length of the novel to just over 117,000 words, but I think no one at the publisher noticed. Their requests for me to make more radical cuts continued for several weeks afterwards, seeming to increase in desperation. The culminating event was a phone call one morning from my then editor. She told me in a panicky voice she had just seen the latest increase in the price of the glue that book binderies used on the spine. Glue! Would I not AT LAST see sense and take out the required 40,000 words of surplus text? I suppose I do not have to spell out what was my gentle and polite response.

In the end The Space Machine appeared in its 117,000-word version on both sides of the Atlantic. It was at that time the longest of my novels, but since then The Prestige, The Separation, The Islanders and now The Adjacent have all been longer. I don’t see any inherent virtue in great length for its own sake – I suppose that I am no different from many other writers, enjoying the freedoms brought to composition by digital technology – but even so my books are by no means the longest around. A few minutes in a bookshop will reveal that my stuff is modest in size, compared with many others.

Word-length aside, my books, at least in hardback, are as large as anyone else’s, and larger than some. By large I mean the dimensions of the pages, the binding.

The first hardcover novel I ever bought was John Wyndham’s Trouble with Lichen. In 1962 it cost me 13s 6d – 68p today, but in those days a substantial sum because my weekly pay was less than £5 a week. Trouble with Lichen was in the then-standard format for hardback fiction in Britain: 7.5″ x 5″, or what printers and binders call Crown Octavo, or C8. At a mere 190 pages it was probably no more than about 60,000 words long.

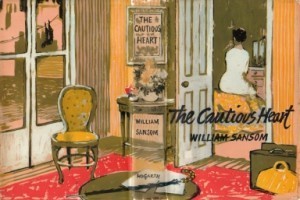

Wyndham was not at all unusual. I have just read a novel by William Sansom called The Cautious Heart, published by Hogarth Press in 1958. This was also printed in C8 and at a quick estimate was about 52,000 words in length. It was not just a good novel to read, it was enjoyable to handle the book, with its compact pages, sewn binding, clear letterpress type, and its unlaminated wraparound cover: a painting of a peaceful interior by Charles Mozley. I like to collect books from the 1950s, mostly because I’m interested in the writers of that period (Wyndham, Sansom, Linklater, Shute, Frankau, among others), but also because I enjoy the quality of the books that were printed then. They must have been the ones I used to see in bookshops during the years I was still at school, impossibly beyond my means.

Wyndham was not at all unusual. I have just read a novel by William Sansom called The Cautious Heart, published by Hogarth Press in 1958. This was also printed in C8 and at a quick estimate was about 52,000 words in length. It was not just a good novel to read, it was enjoyable to handle the book, with its compact pages, sewn binding, clear letterpress type, and its unlaminated wraparound cover: a painting of a peaceful interior by Charles Mozley. I like to collect books from the 1950s, mostly because I’m interested in the writers of that period (Wyndham, Sansom, Linklater, Shute, Frankau, among others), but also because I enjoy the quality of the books that were printed then. They must have been the ones I used to see in bookshops during the years I was still at school, impossibly beyond my means.

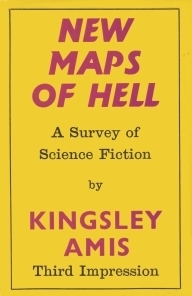

When I started acquiring books seriously in the mid-1960s (becoming a reviewer was a help), many hardbacks were still coming out in C8. For instance, most of Brian Aldiss’s early books from Faber were in that format, as were the Gollancz editions of Kingsley Amis’s first books. The second hardback book I bought, later in 1962, was Amis’s Gollancz title New Maps of Hell. (16s 0d – 80p.) Perhaps because it was non-fiction it was slightly larger than the Wyndham book, more than half an inch taller and slightly wider. This was Large Crown Octavo (abbreviated to LC8, and it is still the size used for many ‘trade’ or ‘B Format’ paperbacks). By the beginning of the 1970s LC8 had become the usual size of hardback fiction. My first novel, Indoctrinaire, in 1970, was in LC8 format, in common with the rest of Faber fiction at the time (and that of most other UK publishers). All the books I published with Faber, up to The Affirmation in 1981, were LC8.

When I started acquiring books seriously in the mid-1960s (becoming a reviewer was a help), many hardbacks were still coming out in C8. For instance, most of Brian Aldiss’s early books from Faber were in that format, as were the Gollancz editions of Kingsley Amis’s first books. The second hardback book I bought, later in 1962, was Amis’s Gollancz title New Maps of Hell. (16s 0d – 80p.) Perhaps because it was non-fiction it was slightly larger than the Wyndham book, more than half an inch taller and slightly wider. This was Large Crown Octavo (abbreviated to LC8, and it is still the size used for many ‘trade’ or ‘B Format’ paperbacks). By the beginning of the 1970s LC8 had become the usual size of hardback fiction. My first novel, Indoctrinaire, in 1970, was in LC8 format, in common with the rest of Faber fiction at the time (and that of most other UK publishers). All the books I published with Faber, up to The Affirmation in 1981, were LC8.

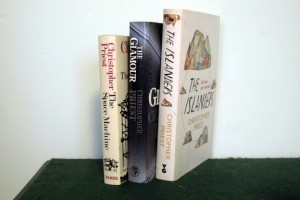

But books were getting bigger again. No different from many other titles at the time, The Glamour, 1984, was printed by Jonathan Cape in Demy Octavo (D8, or slightly larger than LC8). Novels these days are even larger: all my books since The Prestige, 1995, have been in M8 format: Medium Octavo, or 9.5″ x 6″. Even the books of my own that I had printed for Grimgrin were in M8 format – there was little choice: M8 was the only size available in that general range.

But books were getting bigger again. No different from many other titles at the time, The Glamour, 1984, was printed by Jonathan Cape in Demy Octavo (D8, or slightly larger than LC8). Novels these days are even larger: all my books since The Prestige, 1995, have been in M8 format: Medium Octavo, or 9.5″ x 6″. Even the books of my own that I had printed for Grimgrin were in M8 format – there was little choice: M8 was the only size available in that general range.

When a book is published the writer is normally consulted on many aspects: the text, of course, the cover illustration, the blurb. But other matters are at the publisher’s discretion: the typeface, the print-run, the publicity budget, the price – and the size of the pages. I sometimes wonder what the thinking must be. I assume it is partly the result of a calculation which involves the word-length, the number of pages, the type size, the costs involved, the anticipated print-run and the projected eventual retail price of the title. Also, I imagine there are practical constraints. Books are no longer printed on flat sheets (folded into ‘signatures’ of 16 pages each, then sewn into a cloth spine – ‘sewn’ binding), but on large rolls, guillotined in order and stuck with glue into a reinforced paper or plastic spine (called in a misleading way ‘perfect’ binding). You no longer see the tiny signature identifier printed at the bottom left of pages 17, 33, 49, 65 … It’s true to say that although I never really noticed them when they were there, now they are absent I rather miss them.

February 20, 2013

Good Old Friends Mostly Gone

All the spare copies of The Affirmation and The Quiet Woman that I had for sale have now gone to their better places, and I have no more. Thank you to all who ordered, and I hope the books have arrived in good condition.

Copies remain, however, of The Glamour in its beautiful Jonathan Cape hardcover strip. The core price of this book is £4.00 a copy, with £1.00 added for p&p within the UK and Europe. If you live further afield please be prepared to add a little more for surface mail, and even more for airmail. I belatedly discovered the the UK post office has recently removed its concessionary rate for books sent abroad. No doubt this is a sign by officials of their wavering faith in the future of books, which, incidentally, I most certainly do not share.

Copies remain, however, of The Glamour in its beautiful Jonathan Cape hardcover strip. The core price of this book is £4.00 a copy, with £1.00 added for p&p within the UK and Europe. If you live further afield please be prepared to add a little more for surface mail, and even more for airmail. I belatedly discovered the the UK post office has recently removed its concessionary rate for books sent abroad. No doubt this is a sign by officials of their wavering faith in the future of books, which, incidentally, I most certainly do not share.

February 1, 2013

Good Old Friends to Go

An unexpected find: a handful of first editions of some of my older books has come to light, and as storage space is always at a premium in this house without cupboards I would be more than willing to sell a few copies. They are all in brand-new condition, first printings of the first editions, and of course I would be pleased to sign or dedicate copies. They will be protectively and lovingly wrapped for despatch. NB: numbers are strictly limited.

The titles are as follows:

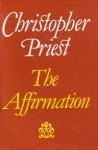

The Affirmation – this is the Faber 1st edition hardcover from 1981, which turned out to be my last book to be published by the firm. (See the item in this blog dated 22nd May 2011, A Quick Read, for some recollections of how it was reviewed in its day.) I always liked the simple, declarative quality of the Faber cover, and in all it is a well printed edition on good paper. Although I never claim The Affirmation as one of my best books, it is first of all a bridge between the books I wrote before it and the ones that were to follow, and secondly I see it as a novel that helps elucidate the others. It was the first novel of mine to include the Dream Archipelago as a setting. Price: £19.00, plus p&p £1.00 in UK and Europe.

The Affirmation – this is the Faber 1st edition hardcover from 1981, which turned out to be my last book to be published by the firm. (See the item in this blog dated 22nd May 2011, A Quick Read, for some recollections of how it was reviewed in its day.) I always liked the simple, declarative quality of the Faber cover, and in all it is a well printed edition on good paper. Although I never claim The Affirmation as one of my best books, it is first of all a bridge between the books I wrote before it and the ones that were to follow, and secondly I see it as a novel that helps elucidate the others. It was the first novel of mine to include the Dream Archipelago as a setting. Price: £19.00, plus p&p £1.00 in UK and Europe.

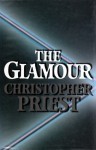

The Glamour – this was my one and only novel to be published by Jonathan Cape, a publisher I moved to in an attempt to escape the clutches of a new editor at Faber, who was out of sympathy with what I was writing. (See Lice in the Locks of Literature, on 9th December 2012.) Although I have revised The Glamour twice since this edition appeared in 1984, the changes have been mostly cosmetic. The major content of the text is unaltered, but for people who take an interest in authors who fiddle around with their novels there are a few unrepeated original thoughts there to be found. Price: £4.00, plus £1.00 p&p in UK and Europe.

The Glamour – this was my one and only novel to be published by Jonathan Cape, a publisher I moved to in an attempt to escape the clutches of a new editor at Faber, who was out of sympathy with what I was writing. (See Lice in the Locks of Literature, on 9th December 2012.) Although I have revised The Glamour twice since this edition appeared in 1984, the changes have been mostly cosmetic. The major content of the text is unaltered, but for people who take an interest in authors who fiddle around with their novels there are a few unrepeated original thoughts there to be found. Price: £4.00, plus £1.00 p&p in UK and Europe.

The Quiet Woman – although I had an excellent experience of having The Glamour published by Cape, by the time I sent in this next book there had been substantial staff changes at the company. Notably, my editor Liz Calder had left Cape, to set up the new publishing venture Bloomsbury. It was not a decision I wanted to have to take, but in the end I followed Ms Calder, and this first edition, in 1990, is one of their early titles. To be honest I never liked the Bloomsbury cover illustration, and overall the book did not do well in this edition. An American edition followed five years later and for that I made some revisions to the text. This text will be used in the forthcoming paperback from Gollancz, but as with The Glamour, the first edition is a chance to read the book as originally presented. Price: £4.00, plus £1.00 p&p in UK and Europe.

The Quiet Woman – although I had an excellent experience of having The Glamour published by Cape, by the time I sent in this next book there had been substantial staff changes at the company. Notably, my editor Liz Calder had left Cape, to set up the new publishing venture Bloomsbury. It was not a decision I wanted to have to take, but in the end I followed Ms Calder, and this first edition, in 1990, is one of their early titles. To be honest I never liked the Bloomsbury cover illustration, and overall the book did not do well in this edition. An American edition followed five years later and for that I made some revisions to the text. This text will be used in the forthcoming paperback from Gollancz, but as with The Glamour, the first edition is a chance to read the book as originally presented. Price: £4.00, plus £1.00 p&p in UK and Europe.

Outside UK and Europe?: please add the equivalent of £2.00 to cover the extra mail cost. Thanks!

More than one title?: Small discounts are offered for 0rders of more than one book. E.g., all three in UK and Europe: £27.00. Please Contact me if you want more details. A unique and perhaps collectable bookmark is included with every copy.

Signed copies: Please let me know if you would like no signature, a signature alone or a signed dedication.

Payment: I can accept PayPal at the Contact email address, or direct bank transfer – details will be sent on request. UK cheques are also acceptable – email me to obtain the address to which they may be sent.

January 7, 2013

The Old Devil

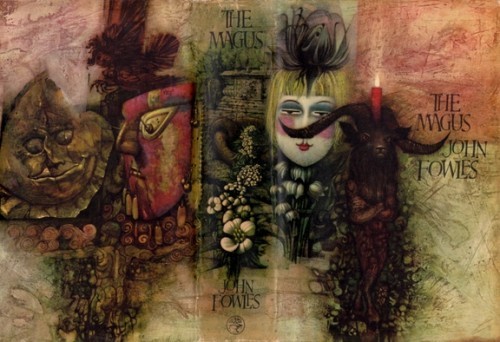

My Christmas present to myself was a copy of John Fowles’s novel The Magus, which I re-read over the holiday period. The copy was a well-preserved UK first edition, which I bought not all that expensively from the Fowlesian specialist book dealer: Magusbooks, run by Bob Goosmann in Sacramento. Mr Goosmann also manages the best website on Fowles, with a mass of biographical and bibliographical detail, background information on Fowles, many photographs, and much interesting trivia (such as a translation from the Latin of the last line of The Magus). The website is here, and has direct links to the bookstore.

The first copy I owned of The Magus was a paperback urged on me in 1970 by my friend Graham Hall. The cover had been torn off because it carried a photograph of the actor Michael Caine, whom Graham loathed. (John Fowles disliked him too, as I discovered many years later). Caine was the star of the 1968 film adaptation of the novel (a pretty terrible film, with a badly chosen cast). Both the film and the novel had passed me by and I had no strong feelings about Michael Caine, but it meant that when I read the book, which came into my hands lacking a blurb and descriptive text of any kind, I had no idea what was in store. Once I had started reading, The Magus glued me to a chair for an entire weekend and overall had a profound impact on me, both as a reader and as a young writer.

The first copy I owned of The Magus was a paperback urged on me in 1970 by my friend Graham Hall. The cover had been torn off because it carried a photograph of the actor Michael Caine, whom Graham loathed. (John Fowles disliked him too, as I discovered many years later). Caine was the star of the 1968 film adaptation of the novel (a pretty terrible film, with a badly chosen cast). Both the film and the novel had passed me by and I had no strong feelings about Michael Caine, but it meant that when I read the book, which came into my hands lacking a blurb and descriptive text of any kind, I had no idea what was in store. Once I had started reading, The Magus glued me to a chair for an entire weekend and overall had a profound impact on me, both as a reader and as a young writer.

Four decades and several re-readings later I’m still convinced it is one of the finest and most influential novels of the last century. The writing is beautiful, in particular in the long descriptive scenes in the first fifty pages or so (the physical descriptions throughout the long novel are executed with precision, delicate language and a vivid visual flair). Much of the story is told through scenes of dialogue, and these are handled plausibly and with a real sense of place, nuance and character.

The story is gripping. In the autumn of 1952 a young English teacher takes up a position at a private school on a small Greek island. By the following summer the schoolmaster, one Nicholas Urfe, has become trapped in an existential cabal conducted by an elderly man called Conchis, who lives on the island in a luxurious villa on the south coast. Urfe’s relationship with Conchis becomes a sort of masque, a ritualistic psychodrama overseen by the self-styled mystic, for which Urfe has apparently been chosen at random. The narrative tells how Urfe is drawn into the conspiracy, how he becomes deeply entangled and what happens when he finally escapes. The plot of the novel is complex, constantly surprising the reader. Towards the end of the book, as Urfe tries to unravel the mystery that has been woven around him, the story takes on the aspect of a thriller, with one revelation after another, opening up the story not to explanation but to a deeper realization of the complexity of the conspiracy. At the end of the novel, the famous final sequence complete with its obscure Latin tag, nothing is clear or resolved in terms of practical explanation, but philosophically both the reader and the central character have moved to a different plane of understanding. It is a choice example of how an undefined or ambiguous ending to a novel places a memorable charge on the reader.

No novel is ever perfect, though, and The Magus has its imperfections. As the years go by they seem more and more problematical, partly because the novel is not yet so old that we can make excuses for it (in the way we tolerate the sexual coyness of novels from the 19th and early 20th centuries, for instance), and partly because Fowles himself was living and working in the modern age. Fowles published the original version of The Magus in 1966, and in 1977 published a fully reworked and revised version. (It was the 1977 edition I re-read last week, incidentally, not my newly acquired first edition.) Fowles should certainly have known by 1977 that sensibilities were changing. His sexualized depiction of two of the young women in the novel (they are in their early 20s, but he usually refers to them as ‘girls’) will offend some people today, as will, and much more acutely, the characterization, description and role of the (alleged) American academic Joseph Harrison.

John Fowles, who died in 2005, is of course not around to defend himself, but he might well argue that the attitudes and mores of the novel accurately reflect those of its period, the early 1950s. However, because the book was published thirteen (and twenty-four) years after its period it is technically an historical novel, a genre which usefully deploys modern sensibility in an ironic or detached way to comment subtly on the past. There is little irony or detachment of this particular social kind in The Magus.

The other problem lies in the long central section of the novel, during which Nicholas Urfe is bemused by the intricacies of the plot that surrounds him. He is constantly questioning his own take on reality. Is this mysterious old man telling him the truth or is everything a fabrication? Have these alluring young women been employed as actors, as he is told, or is a more subtle temptation being put before him? Why are people walking around in masks from Greek mythology? Are those really Wehrmacht soldiers operating in the hills of the island, or are they actors too? Is he free to leave, or is he somehow a captive? And so on. This entire sequence continues to be written in a compelling and intriguing way, and in truth it is not all that tiresome, but it is incredibly long. After the second or third time the women (or one of the women) offer him sexual favours, only to refuse him at the last minute, the reader can’t help wondering why Mr Urfe doesn’t just walk away from the whole damned thing. He sees it through, and so will the reader, with perhaps a sense that the longueurs were justified, but I felt on this re-reading that John Fowles could easily have omitted at least two of Conchis’s long autobiographical recollections, and shortened the rest.

The essential attraction of The Magus lies, I believe, in what you could call extra-literary values.

You do not, for instance, have to read far into the novel to realize that it has a strong autobiographical content. It is known that as a young man John Fowles went to a Greek island to teach English at a large private school. The real island was Spetsai (or, as it has since become, Spetses), and it is in the same part of the Aegean Sea as the fictional Phraxos. He taught there until the summer of 1953, at the end of which he was sacked, in a similar way to Urfe although not for the same reason. The villa on the southern coast of the island is a real one, it is, or was, owned by a reclusive millionaire, and Fowles visited him there. After he left Spetsai, Fowles always swore he could not return to Greece (and did not until the end of his life, when he was taken there by a film-maker), and in general he said little in public about his time on the island.

However, his Journals from that sojourn have been published, and Eileen Warburton’s biography describes his days on Spetsai in detail. Bob Goosmann’s excellent website has more about this period. Fowles himself said, in the Foreword to the 1977 edition, ‘No correlative whatever of my fiction … took place on Spetsai during my stay.’ Even so, and knowing that reality is not the same as fiction, you can’t help experiencing a sense of curiosity about the events that are described in the novel. Fowles’s own denial, or at least his apparent need to make the denial, itself fuels the curiosity. Although many novels are written autobiographically, it is unusual to find one conducted with such intensity, so intriguingly, so enigmatically, and with so many undertones of plausible or even traceable reality.

And there is a sense of something larger, less well defined, behind the book. More than the story you read, more than the language you enjoy and even relish, more than the knowledge you gain of the characters, the reader acquires a sense of complex or profound material. The Magus seems to me to be at least partly about free will and randomness – this is never stated in such explicit terms, but as Urfe begins his quest to find out what had ‘really’ happened on Phraxos, he turns up more and more evidence that the conspiracy was wider than he imagined. Even chance encounters, a girlfriend picked up in a cinema, the landlady of a rented room selected from a postcard in a newsagent’s window, waiters, taxi drivers, newspaper vendors – they all seem to be directly or indirectly connected to the mysterious events at the villa. Maybe by this time Urfe was deep in paranoia, but then so too is the reader, also seeking some kind of rational solution.

I believe it is these extra-literary qualities which have given the novel its enduring qualities, and why it has always appealed (as Fowles himself noted, apparently ruefully) to younger or more open-minded readers. It shares with fantastic fiction that vague sense of ‘something other’, of stating or implying certain truths in outline, of suggesting that life is improvable or at least capable of change, of leaving much to the imagination while exactly and precisely stimulating it with imagined events and an invented story.

Christopher Priest's Blog

- Christopher Priest's profile

- 1064 followers