Martin Fowler's Blog, page 30

January 27, 2016

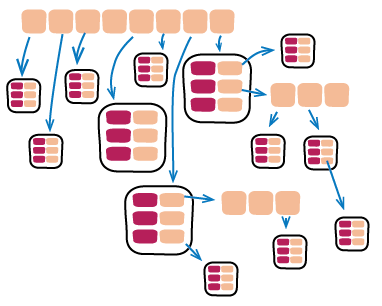

Managing different categories of toggles

Pete has introduced four categories of feature toggles so far. Since these vary

significantly in longevity and dynamism, he now explains how they need to be managed

differently

January 22, 2016

Ops and Permissioning Toggles

January 21, 2016

Release and Experiment Toggles

Pete begins digging deeper into feature toggles by exploring two categories

of feature toggle: release and experiment toggles.

January 19, 2016

Feature Toggles

Feature toggles are a powerful technique, but like most powerful techniques there

is much to learn in order to use them well. And like so much in the software world,

there's precious little documentation on how to work with them. This frustrated my

colleague Pete Hodgson, and he decided to scratch that itch. The result is an article

that I think will become the definitive article on feature toggles.

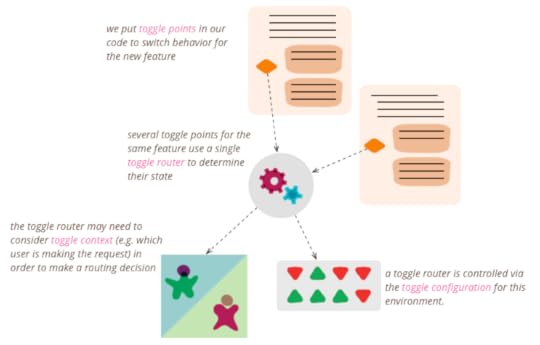

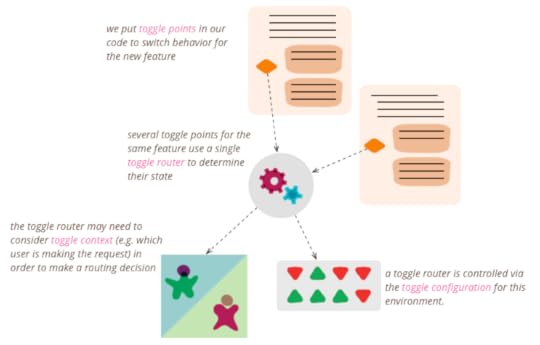

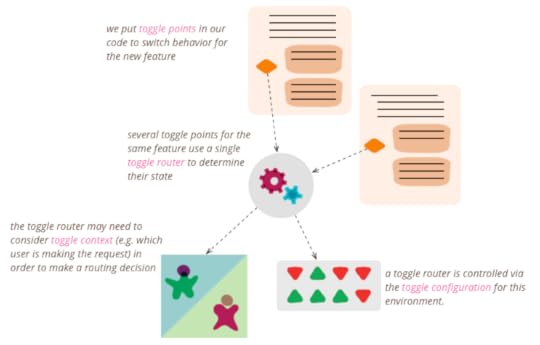

We're going to release this article in installments over the next few weeks. The

first installment sketches out an overview story of how a team uses feature toggles

in a project, and introduces various terms that explain how these toggles work:

toggle points, toggle router, toggle context, and toggle configuration.

December 19, 2015

photostream 93

December 17, 2015

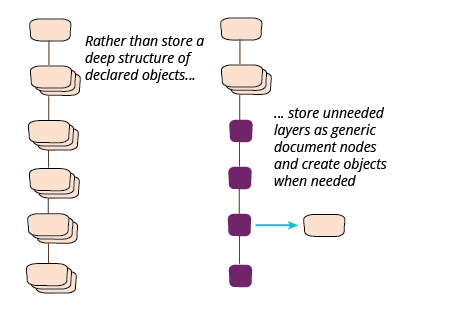

Final part of refactoring document loading - deep objects

Final installment of refactoring the loading of large documents. Here I look at

how to create objects deep in the document tree without declaring the entire tree.

December 15, 2015

Part 2 of Refactoring Code to Load a Document - enriching the document

For the second installment of my article on refactoring the loading of document

data, I'll look at how I can add information to the document for clients,

without declaring the whole document structure as objects.

December 14, 2015

Refactoring Code to Load a Document

Much modern web server code talks to upstream services which return JSON data, do

a little munging of that JSON data, and send it over to rich client web pages using

fashionable single page application frameworks. Talking to people working with such

systems I hear a fair bit of frustration of how much work they need to do to

manipulate these JSON documents. Much of this frustration could be avoided by

encapsulating a combination of loading strategies.

In this first installment, I look at refactoring a fully defined load of a

document to support passing it onto further services and providing an in-process API

to access some of its data.

December 3, 2015

Bliki: ListAndHash

It's now common in many programming environments to represent data structures as a

composite of lists and hashmaps. Most major languages now provide

standard versions of these data structures, together with a rich

range of operations, in particular Collection Pipelines, to

manipulate them. These data structures are very flexible, allowing us to represent

most forms of hierarchy in a manner that's easy to process and

manipulate. [1]

The essence of this data structure is that there are (usually) two

composite data types:

Hashmaps are a key-value data structure, which may be called

associative arrays, hashtables, maps, or dictionaries.

Lists are simple sequences. They're not quite the same as

traditional arrays as they dynamically resize as you add or remove

elements (some languages do call them arrays, however). They can

be indexed by integer keys.

The leaves of the tree can be any other element, commonly the

basic primitives in the language (such as integers and strings),

but also any other structure that isn't treatable as a list or

hash.

In most cases there are separate data types for the list and

hash, since their access operations differ. However, as any lisper

can tell you, it's easy to represent a hash as a list of key-value

pairs. Similarly you can treat a hash with numeric indexes as a list

(which is what Lua's tables do).

A list 'n' hash structure is by default schemaless, the lists can contain disparate

elements and the hashes any combination of keys. This allows the data structure to be

very flexible, but we must remember that we nearly always have an implicit schema

when we manipulate a schemaless data structure, in that we expect certain data to be

represented with certain keys.

A strength of the list and hash structure is that you can

manipulate it with generic operations which know nothing of the

actual keys present. These operations can then be parameterized with

the keys that you wish to manipulate. The generic operations,

usually arranged into a collection pipeline, provide a lot of

navigation features to allow you to pluck what you need from the

data structure without having to manipulate the individual pieces.

Although the usual way is to use flexible hashes for records, you

can take a structure that uses defined record structures (or objects) and

manipulate it in the same way as a hash if those record structures provide reflective

operations. While such a structure will restrict what you can put in

it (which is often a Good Thing), using generic operations to

manipulate it can be very useful. But this does require the language

environment to provide the mechanism to query records as if they are

hashes.

List and hash structures can easily be serialized,

commonly into a textual form. JSON is a

particularly effective form of serialization for such a data

structure, and is my default choice for this. Often XML is used to

serialize list 'n' hash structures, it does a serviceable job, but

is verbose and the distinction between attributes and elements makes

no sense for these structures (although it makes plenty of sense for

marking up text).

Despite the fact that list 'n' hashes are very common, there are times I wish I was

using a thoughtful tree representation. Such a model can provide richer navigation

operations. When working with the serialized XML structures in Nokogiri, I find it handy to

be able to use XPath or CSS selectors to navigate the data structure. Some kind of

common path specification such as these is handy for larger documents. Another issue is

that it can be more awkward than it should to find the parent or ancestors of a given

node in the tree. The presence of rich lists and hashes as standard equipment in modern

languages has been one of the definite improvements in my programming life since I

started programming in Fortran IV, but there's no need to stop there.

Acknowledgements

David Johnston, Marzieh Morovatpasand, Peter Gillard-Moss, Philip Duldig, Rebecca

Parsons, Ryan Murray, and Steven Lowe

discussed this post on our internal mailing list.

Notes

1:

I find it awkward that there's no generally accepted,

cross-language term for this kind of data structure. I could do

with such a term, hence my desire to make a Neologism

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

Bliki: EvolvingPublication

When I was starting out on my writing career, I began with

writing articles for technical magazines. Now, when I write

article length pieces, they are all written for the web. Paper

magazines still exist, but they are a shrinking minority, probably

doomed to extinction. Yet despite the withering of paper

magazines, many of the assumptions of paper magazines still exact

a hold on writers and publishers. This has particularly risen up

in some recent conversations with people working on articles I

want to publish on my site.

Most web sites still follow the model of the Paper Age.

These sites consist of articles that are grouped primarily due to

when they were published. Such articles are usually written in one

episode and published as a whole. Occasionally longer articles are

split into parts, so they can be published in stages over time (if

so they also may be written in parts).

Yet these are constraints of a paper medium, where updating

something already published is mostly impossible. [1] There's no

reason to have an article split over distinct parts on the web,

instead you can publish the first part and revise it by adding

material later on. You can also substantially revise an

existing article by changing the sections you've already published.

I do this whenever I feel the need on my site. Most of the

longer-form articles that I've published on my site in the last

couple of years were published in installments. For example, the popular article on

Microservices was originally published over nine installments

in March 2014. Yet it was written and conceived as a single

article, and since that final installment, it's existed on the web

as a single article.

Our first rationale for publishing in installments is the

notion that people tend to prefer reading shorter snippets these

days, so by releasing a 6000 word article in nine parts, we could

keep each new slug to a size that people would prefer to read. A

second reason is that multiple

publications allows for more opportunities to grab people's

attention, so makes it more likely that an article will find

interested readers.

When I publish in installments, I add an item to my news feed and

tweet for each installment. Since I'm describing an update, I link with a

fragment URL to take readers to the new section (in future I may

link to a temporary explanatory box to highlight what's in the new

installment).

But whatever the way the article is released to the world, it

is still a single conceptual item, so its best permanent form is a

single article. Many people have read the microservices article since that

March, and I suspect hardly any of them knew or cared that it was

originally published in installments.

In that case we wrote the entire article before we started the

installment publishing, but there's no reason against writing it

in stages too. For my collection pipelines article, I wrote and

published the original article over five installments in July

2014. As I was writing it, I was conscious that there were

additional sections I could add. I decided to wait to see how the

article was received before I put the effort in to write those

sections.

Since it was pretty popular, I made a number of revisions, for each one I

announced it with a tweet and

an item on my feed.

Letting an article evolve like this is the kind of thing

that's difficult in a print medium, but exactly the right thing to

do on the web. A reader doesn't care that I revised the article to

improve it, she just wants to read the best explanation of the

topic at hand.

I do like to provide some traces of such revisions.

At the end of each article, I include a revision history which

briefly summarizes the changes. For a couple of revisions, such as

the 2006 revision of my article on Continuous Integration, I made

the original article available on a different URL with a link from

the revised article. I don't think the original article is useful to most readers,

only really to those tracing the intellectual history of the idea,

so shifting the original to a new URL makes sense.

The role of the feed is important in this. The traditional blog

reinforces the Paper Age model by encouraging people to match an article

with its feed entry. For longer articles, I prefer to consider

them as different things, the feed is a notice of a new article or

revision, which links to the article concerned. That way I

generate feed entries each installment where the feed summarizes

what's been added.

The point of all this is that we should consider web articles

as information resources, resources that can and should be

extended and revised as our understanding increases and as time

and energy allow. We shouldn't let the Print Age notions of how

articles should be constructed dictate the patterns of the

Internet Age.

Notes

1:

There is a sort of an update mechanism, in that a series of

articles might be republished as a single work. But that is

relatively rare.

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

Martin Fowler's Blog

- Martin Fowler's profile

- 1099 followers