Brian Clegg's Blog, page 148

February 9, 2012

Good science, bad science

Something I try to get in books and talks that an awful lot of people presenting science skim over is that science isn't about absolute fact. All science can ever be is our best guess given the current data. Tomorrow new data may emerge that totally overthrows our current thinking.

This has happened repeatedly in the past. Something like Newton's laws of motion can seem set in stone (hence the 'laws' label, which I don't think is a good idea). And then along comes Einstein and shows they are wrong. Not wrong enough to throw them away - they still work well in many circumstances - but wrong nonetheless.

This is why I get a bit irritated when popular science presenters and writers make sweeping statements like 'the universe began 13.7 billion years ago in the big bang.' What they should be saying is 'according to our best supported current theory, which fits the data well (though it's not entirely surprising as bits of it have been changed to do so), the universe began 13.7 billion years ago in the big bang.' Now, I admit that's rather clumsy - but I think every popular science book should have a proviso that what is being described as if it were fact is the current best theory, and this may change.

Note that this isn't an argument in support of the 'evolution is just a theory, so we ought to teach intelligent design' brigade. I didn't say a 'current theory'. I said the current best theory - the one best supported by the evidence and that works well with our other current best theories. This is not a recipe for taking any old hypothesis with the same confidence as the best theory. But it is bad science to suggest that our favourite theories (especially those like the cosmological ones which are based on very indirect data) are fact.

That's one kind of bad science. Another is cheating. We tend to think of scientists as emotionless seekers after the truth, but if you ever meet a scientist (treat them nicely - buy them a drink!) most are normalish human beings. With human tendencies. And there is a well established psychology of the way we fool ourselves in order to get the results we want. This inevitably happens in science. Some of the best known experiments in science have not really produced the results the scientist wanted. So they just went ahead and ignored the results. Newton, for instance, didn't get what he really wanted in his experiments with light using prisms. No matter. He knew the desired result and that's what he wrote up. Whenever anyone writes about general relativity, they talk of Eddington's 1919 Principe expedition which proved the expect effect of the Sun bending light. Only it didn't - certainly not within acceptable margins of error. But Eddington announced the result he wanted.

It would be silly to think that this doesn't happen all the time, and I'm delighted to be able to show the graphic below (technically an 'infographic' but I hate the term) from Tony Shin and his team (I've seen it elsewhere, but it's worth repeating) on the subject. I ought to say that we shouldn't take this as all bad. Many experiments are't fiddled. Just because a result is tweaked doesn't mean it's wrong. And over time science's system of repeating results ensures that problems are ironed out. But we can't pretend it doesn't happen:

[image error]

Created by: ClinicalPsychology.net

This has happened repeatedly in the past. Something like Newton's laws of motion can seem set in stone (hence the 'laws' label, which I don't think is a good idea). And then along comes Einstein and shows they are wrong. Not wrong enough to throw them away - they still work well in many circumstances - but wrong nonetheless.

This is why I get a bit irritated when popular science presenters and writers make sweeping statements like 'the universe began 13.7 billion years ago in the big bang.' What they should be saying is 'according to our best supported current theory, which fits the data well (though it's not entirely surprising as bits of it have been changed to do so), the universe began 13.7 billion years ago in the big bang.' Now, I admit that's rather clumsy - but I think every popular science book should have a proviso that what is being described as if it were fact is the current best theory, and this may change.

Note that this isn't an argument in support of the 'evolution is just a theory, so we ought to teach intelligent design' brigade. I didn't say a 'current theory'. I said the current best theory - the one best supported by the evidence and that works well with our other current best theories. This is not a recipe for taking any old hypothesis with the same confidence as the best theory. But it is bad science to suggest that our favourite theories (especially those like the cosmological ones which are based on very indirect data) are fact.

That's one kind of bad science. Another is cheating. We tend to think of scientists as emotionless seekers after the truth, but if you ever meet a scientist (treat them nicely - buy them a drink!) most are normalish human beings. With human tendencies. And there is a well established psychology of the way we fool ourselves in order to get the results we want. This inevitably happens in science. Some of the best known experiments in science have not really produced the results the scientist wanted. So they just went ahead and ignored the results. Newton, for instance, didn't get what he really wanted in his experiments with light using prisms. No matter. He knew the desired result and that's what he wrote up. Whenever anyone writes about general relativity, they talk of Eddington's 1919 Principe expedition which proved the expect effect of the Sun bending light. Only it didn't - certainly not within acceptable margins of error. But Eddington announced the result he wanted.

It would be silly to think that this doesn't happen all the time, and I'm delighted to be able to show the graphic below (technically an 'infographic' but I hate the term) from Tony Shin and his team (I've seen it elsewhere, but it's worth repeating) on the subject. I ought to say that we shouldn't take this as all bad. Many experiments are't fiddled. Just because a result is tweaked doesn't mean it's wrong. And over time science's system of repeating results ensures that problems are ironed out. But we can't pretend it doesn't happen:

[image error]

Created by: ClinicalPsychology.net

Published on February 09, 2012 08:26

February 8, 2012

So good they named him twice

I get plenty of unsolicited emails because my email address is publically available on a website. I don't mind too much because just occasionally amongst the dross I get an email that gives me so much pleasure that it's worth the drudgery of sweeping away the rubbish. And one came today.

I get plenty of unsolicited emails because my email address is publically available on a website. I don't mind too much because just occasionally amongst the dross I get an email that gives me so much pleasure that it's worth the drudgery of sweeping away the rubbish. And one came today.The image to the right is the opening of the email. In it we learn that William O'Connor (I presume that is he in the photo):

boasts over 30 years in active mediumship and psychic consultations with a wide array of achievements including TV and Radio. William has been active in the spiritualist movement in Scotland for many years not to mention psychic floor shows in front of large audiences.What's more:

William and his psychics will be at the Body & Soul Fair at Glasgow Royal Concert Hall on 25th and 26th February. Our psychics will be available to provide private readings, 20 minutes for £30.Just in case you get too excited, though, I ought to point out that your psychic reading on the phone is not by the psychic psychic himself, but instead you will be connected 'to a psychic who is fully trained and mentored by William O'Connor.' A sort of homeopathic psychic.

Demand is sure to be high so book your reading now, for a time which suits you!

I was going to every so slightly poke fun at this email, but really I don't need to. It does the job without help. Similarly I had considered putting in a proviso that by mentioning this, I in no way endorse it, because in my opinion some psychics are frauds, some are totally genuine in their belief but deluded - but to be honest I don't need to do that either. I trust too much in the intelligence of my readership. Instead, then, I intend to roll about the floor laughing at the concept of a psychic reading taking place on a meter at 80p a minute. Exuse me while I ROFL.

Published on February 08, 2012 08:33

February 7, 2012

Ah, vanity

Every now and then, when I've nothing better to do, I examine the backs of cosmetic bottles and other gubbins that are found lying around the house. (Yes, this is the kind of exciting life a science writer has.)

Every now and then, when I've nothing better to do, I examine the backs of cosmetic bottles and other gubbins that are found lying around the house. (Yes, this is the kind of exciting life a science writer has.)What I see on the back of some of those bottles is a mystery to me. Actually, a number of mysteries.

Mystery #1 is why some products have a contents list and some don't. The fact that some don't seems to imply it isn't required. So why do it at all? (It could be it's specific products, or it's on the cardboard box instead. Dunno.)

Mystery #2 is who do they think they are fooling with 'aqua'? Pretty well all cosmetic bottle contents have water as their number one ingredient, but the manufacturer seems to think that they can make it sound more impressive by calling it 'aqua'. Only they also seem obliged to give the game away as it is, in fact, always called 'aqua (water)'. So why bother with the 'aqua'? It just makes you seem silly, guys.

Mystery #3 is how a particular company making the product seen above (and for all I know many others do this also) managed to make themselves look even more stupid. Because the next entry is wonderfully bizarre. It's 'Paraffinum liquidum (Mineral oil)'.

Mystery #3 is how a particular company making the product seen above (and for all I know many others do this also) managed to make themselves look even more stupid. Because the next entry is wonderfully bizarre. It's 'Paraffinum liquidum (Mineral oil)'.Okay, let's break this down. Firstly 'Paraffinum liquidum' sounds more like a rather bad Harry Potter spell than an ingredient. Secondly, it doesn't take a classical education to work out that 'Paraffinum liquidum' is liquid paraffin. You know, that stuff your granny used to put in her portable heater. Actually, a classical education is the last thing you want here. Admittedly 'liquidus' is the Latin for liquid, so they were quite close there, but 'paraffin' is not taken from a Latin word so this is pure pig Latin.

I can see they realize people wouldn't want to know that they are coating themselves in paraffin, but this hardly conceals it, does it guys? They would have been better off sticking to the much more natural and friendly sounding 'Mineral oil' (it must be good for you, it has minerals). Admittedly all this means is something extracted from crude oil - technically petrol and diesel are mineral oils - but it sounds so much better.

So there we have it. Is there a sillier contents label? Almost certainly. But I am yet to find it.

Published on February 07, 2012 09:23

February 6, 2012

Loving Yasiv

Occasionally someone will come up with a web app that hasn't got any real benefit in life, the universe and everything, but that's great fun. And surely this is not a bad thing.

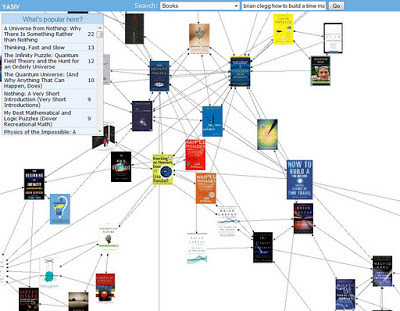

Occasionally someone will come up with a web app that hasn't got any real benefit in life, the universe and everything, but that's great fun. And surely this is not a bad thing.Thanks to @thecreativepenn for pointing out Yasiv.com. Put in a product listed on Amazon.com and you will see a diagram of related purchases.

The developer sees this as being a good way to think 'if other people bought this as well, then perhaps I should look at these too.'

But also if you happen to have produced a product that's sold on Amazon, then it is rather fun to take a look at these 'related' products and what other things people bought. It doesn't just apply to books - you can do it with anything on Amazon.com (though not at the moment .co.uk - I emailed the developer to ask, and it's on his to-do list). Give it a try...

Published on February 06, 2012 08:08

February 3, 2012

Antimatter apples

I had a lovely time on Wednesday evening giving a talk based on

How to Build a Time Machine

at Pewsey Library. I don't know what it is about Pewsey, but this is the second time I've spoken there, and again we had some brilliant questions, which tend to range over all of physics.

A couple were on gravity, which is rather nice as it's the subject of my next St Martin's Press book, due out later this year. And one was particularly timely. Someone asked, given that both electricity and magnetism have positive and negative aspects, was there anything that repelled gravitationally, rather than attracting.

A couple were on gravity, which is rather nice as it's the subject of my next St Martin's Press book, due out later this year. And one was particularly timely. Someone asked, given that both electricity and magnetism have positive and negative aspects, was there anything that repelled gravitationally, rather than attracting.

It's timely because an experiment is underway to try to determine whether antimatter is gravitationally attracted by matter or repelled by it. I had always assumed antimatter was just like ordinary matter, behaving exactly the same way in everything except its electrical charge. So I was quite surprised when reading a book by George Gamow on gravity that he suggested it might be repelled gravitationally by ordinary matter. When a scientist of Dr Gamow's stature suggests something, you take it seriously.

You might think this is trivial to test, but it's not. Firstly we've only got tiny amounts of antimatter - and it doesn't usually stay around long before annihilating with normal matter. And also gravity is a very weak force. It might not seem it if you try to jump off the Earth, but just think about it. When I hold a fridge magnet near the fridge and let go, it has the whole Earth pulling it downwards and just a tiny magnet pulling it towards the fridge. The magnet wins. Gravity is vastly weaker than electromagnetism, making it very difficult to detect and distinguish gravitational effects in tiny particles of antimatter.

It will be fascinating to find out which way the antimatter goes. Apart from anything else, it has an implication for the principle of equivalence. This was what inspired Einstein towards general relativity, his theory of gravitation. The idea of equivalence is that if you were in an enclosed spaceship with no connection with the outside world, at any point in the spaceship you couldn't tell if you were feeling a gravitational pull or being accelerated by the ship's motors. The effect would be identical. They are equivalent. But if you had a piece of antimatter, and it is indeed repelled by ordinary matter, you would be able to distinguish. It doesn't really matter for general relativity, but it would mean a proviso had to be inserted into equivalence.

Let's wait and see. I rather hope the antimatter is repelled by matter. After all, it would make the universe even more exotic.

A couple were on gravity, which is rather nice as it's the subject of my next St Martin's Press book, due out later this year. And one was particularly timely. Someone asked, given that both electricity and magnetism have positive and negative aspects, was there anything that repelled gravitationally, rather than attracting.

A couple were on gravity, which is rather nice as it's the subject of my next St Martin's Press book, due out later this year. And one was particularly timely. Someone asked, given that both electricity and magnetism have positive and negative aspects, was there anything that repelled gravitationally, rather than attracting.It's timely because an experiment is underway to try to determine whether antimatter is gravitationally attracted by matter or repelled by it. I had always assumed antimatter was just like ordinary matter, behaving exactly the same way in everything except its electrical charge. So I was quite surprised when reading a book by George Gamow on gravity that he suggested it might be repelled gravitationally by ordinary matter. When a scientist of Dr Gamow's stature suggests something, you take it seriously.

You might think this is trivial to test, but it's not. Firstly we've only got tiny amounts of antimatter - and it doesn't usually stay around long before annihilating with normal matter. And also gravity is a very weak force. It might not seem it if you try to jump off the Earth, but just think about it. When I hold a fridge magnet near the fridge and let go, it has the whole Earth pulling it downwards and just a tiny magnet pulling it towards the fridge. The magnet wins. Gravity is vastly weaker than electromagnetism, making it very difficult to detect and distinguish gravitational effects in tiny particles of antimatter.

It will be fascinating to find out which way the antimatter goes. Apart from anything else, it has an implication for the principle of equivalence. This was what inspired Einstein towards general relativity, his theory of gravitation. The idea of equivalence is that if you were in an enclosed spaceship with no connection with the outside world, at any point in the spaceship you couldn't tell if you were feeling a gravitational pull or being accelerated by the ship's motors. The effect would be identical. They are equivalent. But if you had a piece of antimatter, and it is indeed repelled by ordinary matter, you would be able to distinguish. It doesn't really matter for general relativity, but it would mean a proviso had to be inserted into equivalence.

Let's wait and see. I rather hope the antimatter is repelled by matter. After all, it would make the universe even more exotic.

Published on February 03, 2012 08:39

February 2, 2012

Left brain, scmeft brain

I'm in the editing process on a book at the moment, and had mentioned the idea of the left brain/right brain split in terms of creativity. There are two concepts involved here. One is that you effectively have two brains. The left and right halves are pretty well separate, joined only at the corpus collosum, the big bundle of nerves at the back. The second is that the we have two distinct modes of operation, one is 'left brain' thinking that deals with the logical, sequential, verbal, rational, analytic, linear style of thinking. The other, 'right brain' thinking deals with the overview, spatial thinking, colour, art, imagery and the like. The assertion is that for creativity it is good to have both sides of the brain active, but when we settle down in a meeting (say) we tend to plug solidly into left brain mode.

Now my editor pointed out that there as been some doubt cast on the left brain/right brain split in this regard. (And, to be fair, I had actually said this, just not clearly enough). With evidence from fMRI and the like it becomes clear that both sides of the brain are involved in both types of thinking. However, what I was saying in the book is that the 'left brain' and 'right brain' labels are still quite useful, because there certainly are two clear modes of operation corresponding to these types of attribute.

If you'd like to feel your brain switch modes, there is a simple exercise you can do to experience it. Run the video below. It will put up a series of words. Your task is to say out loud the colour each word is printed in. Ignore what the word says, just say the colour. It's important that you do it out loud. Try it now:

What you should feel is a grunge as your brain desperately tries to switch mode. It doesn't matter what I told you, it pretty soon accepts it's dealing with words and selects left brain mode. Then, panic, it has to engage right brain. After a few words it should settle down and be fine again.

So, yes, technically the labels are out of date. But then so is the direction of flow of current in electricity, which goes the opposite way to the electrons. But it's still quite handy to use the left/right brain tags.

Now my editor pointed out that there as been some doubt cast on the left brain/right brain split in this regard. (And, to be fair, I had actually said this, just not clearly enough). With evidence from fMRI and the like it becomes clear that both sides of the brain are involved in both types of thinking. However, what I was saying in the book is that the 'left brain' and 'right brain' labels are still quite useful, because there certainly are two clear modes of operation corresponding to these types of attribute.

If you'd like to feel your brain switch modes, there is a simple exercise you can do to experience it. Run the video below. It will put up a series of words. Your task is to say out loud the colour each word is printed in. Ignore what the word says, just say the colour. It's important that you do it out loud. Try it now:

What you should feel is a grunge as your brain desperately tries to switch mode. It doesn't matter what I told you, it pretty soon accepts it's dealing with words and selects left brain mode. Then, panic, it has to engage right brain. After a few words it should settle down and be fine again.

So, yes, technically the labels are out of date. But then so is the direction of flow of current in electricity, which goes the opposite way to the electrons. But it's still quite handy to use the left/right brain tags.

Published on February 02, 2012 09:33

February 1, 2012

The joy of coincidence

If you've been around here recently you would have heard that the UK edition of How to Build a Time Machine, which is confusingly called Build Your Own Time Machine over here, is out and about with a rather smart retro cover. I've recently discovered a wonderful coincidence concerning the cover.

If you've been around here recently you would have heard that the UK edition of How to Build a Time Machine, which is confusingly called Build Your Own Time Machine over here, is out and about with a rather smart retro cover. I've recently discovered a wonderful coincidence concerning the cover.One chapter of the book is dedicated to Ronald Mallett, an American physics professor who has spent his life working on the general relativity and its applications to time travel. He was inspired to do this because his father died when he was a boy, and when he came across the concept of a time machine he realised that he wanted to make one of these to go back and see his dad again.

The initial idea came to young Ron while reading a comic book version of the H. G. Wells classic, The Time Machine. And here's the wonderful coincidence (thanks to tbrosz on Litopia for pointing this out). The UK cover isn't just a pastiche of the old science fiction style, it is based on a specific comic book cover.

You guessed it. That same comic that inspired Ronald Mallett also inspired the designer of my book's cover. And, as far as I can tell, it is pure coincidence. Here's the cover from www.tkinter.smig.net/ClassicsIllustrated

Published on February 01, 2012 08:28

January 30, 2012

The Bulgarian connection

I still can't quite believe that I recently appeared on Bulgarian TV. Speaking in Bulgarian. (Sort of.) It was all rather surreal.

I still can't quite believe that I recently appeared on Bulgarian TV. Speaking in Bulgarian. (Sort of.) It was all rather surreal.The interview took place via Skype, between me, sitting at my desk in my office and the glamorous presenter, Sophia Tzavella, in a sizeable serious TV studio.

We discussed various weird aspects of science in English. They have then dubbed over us (presumably Sophia dubbed herself) in Bulgarian, so you hear the voice of a suitably scientific sounding Bulgarian actor.

If you would like to take a look at me in action, it's available online here. I'm on from about 7 minutes 17 seconds, but I particularly like the shot at 8 minutes 4 seconds (screenshot on the left) which shows the studio in all its glory with me on a big screen in the background.

If you would like to take a look at me in action, it's available online here. I'm on from about 7 minutes 17 seconds, but I particularly like the shot at 8 minutes 4 seconds (screenshot on the left) which shows the studio in all its glory with me on a big screen in the background.All in all a fascinating experience!

Published on January 30, 2012 08:45

January 27, 2012

One more Time

Time, as they say, waits for no person. Neither do books about time machines. Because I'm delighted to say the UK version of my book on the science of time travel, Build Your Own Time Machine is now available. I didn't get my own copies until the very last minute, so it's brilliant to be able to see it for real at last.

Time, as they say, waits for no person. Neither do books about time machines. Because I'm delighted to say the UK version of my book on the science of time travel, Build Your Own Time Machine is now available. I didn't get my own copies until the very last minute, so it's brilliant to be able to see it for real at last.So run, don't walk to your local Waterstones and demand a copy yesterday. Or even easier, nip over to Amazon (there are links to do so on the book's web page) and order one up.

At risk of being a touch biassed, this is one of my favourites of all the books I've written. Time travel. What's not to love?

I'm glad to say the publisher was able to respond to a concern about the cover. The original version didn't have the subtitle, which meant there was nothing to distinguish it from a science fiction book. They were able to slip in 'The Real Science fo Time Travel', which is great.

I'm expecting talks based on this book to be popular - there are already a couple booked, at Pewsey Library at 7.30pm on 1 February, at the Scottish Storytelling Centre as part of the Edinburgh International Festival of Science at 5.30 on 2 April and at the Brympton Festival at 1pm on Sunday 22 April. You can always keep an eye on my upcoming events on the web page.

Published on January 27, 2012 08:24

January 26, 2012

Mr Newton's Rainbow

I'm currently reading for review a book called Quantum Physics for Poets (the next step, I suppose, from How to Teach Physics to your Dog). In it, the authors comment

I'm currently reading for review a book called Quantum Physics for Poets (the next step, I suppose, from How to Teach Physics to your Dog). In it, the authors commentA glass prism hanging in our window splits the white sunlight into its spectral constituents Red-Orange-Yellow-Green-Blue-Indigo-Violet (ROY G. BIV)Now, leaving aside the rather bizarre idea that 'Roy G. Biv' is somehow a useful way of remembering anything, I thought it rather sad that this book, written by a Nobel laureate and friend, passes on as wisdom without comment the idea that there are seven colours in the rainbow. It's a load of tosh, for which we have to thank Isaac Newton.

If you take a look at a rainbow and look for blocks of colour, it's hard to see more than six. Alternatively, if you consider the rainbow of colours on your computer screen, it is likely to be made up of millions of subtly different hues. Either way you consider it, seven is wrong.

There's a good reason for this. There was no scientific basis for Newton's assertion that there are seven colours. We aren't absolutely certain, but the best supported theory for why he came up with this number is because there are seven musical notes - A to G - before you come back to the A in the octave. If music had seven notes, Newton seems to have argued, a rainbow should have seven colours, and he came up with a set to match.

Interestingly, he was lucky to be able to come up with those particular colours. One of Roy G. Biv's constituents didn't exist a few decades earlier. When I do talks on this subject and ask people to guess which colour didn't exist they usually go for one of the obscure colours at the far end of the spectrum, but in fact it was orange. The word existed. It was the name of a fruit. (Still is.) But the colour didn't take its name from the fruit until the 1600s.

Newton did many wonderful things, and contributed vastly to science. But his rainbow colour scheme was a bit of a fraud.

Image from Wikipedia: D-Kuru/Wikimedia Commons

Published on January 26, 2012 08:19