Brian Clegg's Blog, page 15

March 11, 2024

A PR triumph

I get a lot of press releases, but I have enjoyed few more than one I recently got from a book review website called Summary Guru, which site carries the headline 'GET INSPIRATION FOR YOUR PAPER WITH AI POWERED BOOK SUMMARIES & ANALYSIS – PLAGIARISM FREE' (Does inspiration need to be plagiarism free? Or just stuff you copy and paste?)

I get a lot of press releases, but I have enjoyed few more than one I recently got from a book review website called Summary Guru, which site carries the headline 'GET INSPIRATION FOR YOUR PAPER WITH AI POWERED BOOK SUMMARIES & ANALYSIS – PLAGIARISM FREE' (Does inspiration need to be plagiarism free? Or just stuff you copy and paste?)To demonstrate the effectiveness of Summary Guru, the release tells us 'Before Watching Netflix's One Day, Know These Five Fascinating Details From The Book' - details produced by Summary Guru. Here they are, with a few of my comments:

1. It's about a single day... across twenty years

To be honest, if you don't know this before watching the series, you haven't being paying attention.

2. It deeply explores relationships

This is illustrated with 'To quote Emma (the novel’s main female character): “Dexter, I love you so much…and I probably always will. I just don't like you anymore. I'm sorry.”' Yep, deep.

3. The book is rich in philosophy

Take a sabbatical, philosophy lecturers. Apparently 'Nicholls sprinkles many philosophical ideas through the book, highlighted by quotes such as, ‘’I think reality is overrated’’ and ‘’There is always joy in witnessing the joy of others.”' Wow, why did I bother reading philosopher Philip Goff's book on the purpose of the universe?

4. It's light and dark.

This a real step forward for a fiction title, I think. We should see more of it, novelists.

5. There are bursts of humour

We are told 'But it’s not all doom and gloom; here are two light-hearted quotes that illustrate how funny Nicholls's prose can be:

“Oh, you know me. I have no emotions. I'm a robot. Or a nun. A robot nun.”“Call me sentimental, but there's no one in the world that I'd like to see get dysentery more than you.”LOL.I know press releases are easy targets, but this feels more like a parody than the real thing. Perhaps it was intended as irony, but I'm not sure it was.

In case the release inspires you to get a copy of One Day, it is available from amazon.co.uk, amazon.com and bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free hereMarch 5, 2024

Billiard balls and time

I've recently been reading The Blind Spot, which describes how science tends to confuse its idealised and simplified models with reality, and how scientists have traditionally relied too much on reductionism while putting anything that involves human experience into the 'unreliable and subjective' box, even though everything we do in the sciences (as opposed to mathematics) requires the input of human experience.

I've recently been reading The Blind Spot, which describes how science tends to confuse its idealised and simplified models with reality, and how scientists have traditionally relied too much on reductionism while putting anything that involves human experience into the 'unreliable and subjective' box, even though everything we do in the sciences (as opposed to mathematics) requires the input of human experience.One of the subjects covered at length in the book is time. This is fascinating in the context, because time is the experiential phenomenon that is regarded most differently in physics than it is in reality. Some physicists go as far to say that time doesn't exist at all. Related to this, it is pointed out that many physical processes are reversible in time, where science does not care which way it goes. But in the The Blind Spot the authors emphasise that what we experience is not clock time - the only time that physics regards as real - but duration. Physics, for example, has something of a problem with the 'arrow of time' - the idea that time has a specific 'direction' - outside of some specific areas like the second law of thermodynamics. This is something that is obvious when you see time through the perspective of duration but is not, for instance, present in say the laws of motion.

I've always thought one of the best demonstrations of why traditional physics gets this wrong, proving what the authors of The Blind Spot put across rather clumsily, is the very simple classical physics example of two billiard balls heading towards each other, colliding and heading away from each other. This is often used an example of the time reversibility of such physics. If you had a video showing the balls heading for each other, colliding and heading away, you could run it forward or backwards and it would be impossible to distinguish the two. And this is echoed in the maths.

But what The Blind Spot points out (though without using such an easily considered example) is that what we are doing here is giving a mathematical model the status of reality, where it is in fact an abstraction that doesn't reflect reality. One reason for taking this view is that a real billiard table has friction and the balls will loose energy in the collision, so will be travelling slower after the collision that before. But that's relatively trivial. The big blind spot here is a trap that physicists love to tease psychologists about falling into: cherry picking. We are not using what is observed in the real world, just a part of it. In reality, something had to start those billiard balls moving... and before long they will stop. In the real world, taking a durational view of time, there is no doubt at all that time is not reversible. It is only by cherry picking the frames of the video in the middle that we can pretend that the mathematical abstraction of Newton's laws, using clock time, that enable us to be so dismissive of time.

In the end, some physicists may say time doesn't exist (in the sense of elapsing through duration), but I've never seen a physicist who doesn't know how long it is until dinner time.

Image by Rangakuvara from Wikimedia Commons CC4.0 - I've no idea what the guy with the cue thinks he's doing.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free hereFebruary 27, 2024

Why is an insect like a leased aircraft?

Lewis Carroll famously came up with the nonsense riddle ‘Why is a raven like a writing desk?’ - which was never intended to have a meaningful answer. But for some reason a piece of science news I read in Physics World inspired the question in the title of this post: why is an insect like a leased aircraft?

Lewis Carroll famously came up with the nonsense riddle ‘Why is a raven like a writing desk?’ - which was never intended to have a meaningful answer. But for some reason a piece of science news I read in Physics World inspired the question in the title of this post: why is an insect like a leased aircraft?The leased aircraft in question was one that British Airways borrowed from Aer Lingus. The plane was then repainted in BA colours for the duration. But part of the deal involved repainting the aircraft in the Irish airline’s livery and generally putting it back with the configuration Aer Lingus required before returning it. When the engineers finished, they fixed a little plaque to the instrument panel in the cockpit reading ‘FLY GREEN SIDE UP.’

The science story that made this come to mind was the answer to a long-term puzzle: why do insects seem to be so attracted to lights at night? I had heard the suggestion that they used the Moon to help with navigation - but the study shows that they don’t fly towards light. Instead they turn their backs to the light, apparently because with a natural light source this essential gives them the correct orientation for ‘fly this side up’. Light is treated as an indicator of upwards, which is why, for instance, they often fly around a light at an angle. You can read the details here.

One last thing. Previous generations wondering why a raven is like a writing desk could not consult an AI. I asked ChatGPT and Gemini (the renamed Bard) for their thoughts. Of the two I preferred the answer from Gemini, which is below:

This famous riddle from Lewis Carroll's "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" has no definitive answer, and that's part of the point! Carroll himself offered several playful solutions:

Because it can produce a few notes, though they are very flat; and it is never put with the wrong end in front! (Early versions spelled "never" as "nevar," mirroring the reversed letters in "raven.")Because Poe wrote on both. (Referencing Edgar Allan Poe, known for his dark poems and stories.)Because they both come with inky quills.However, the beauty of the riddle lies in its openness to interpretation. Here are some other creative solutions people have come up with:

Because one has flapping fits and the other has fitting flaps.Because one is good for writing books and the other better for biting rooks.Because a raven is nevaR backwards and a writing desk is for Words. (A play on words and spelling.)Ultimately, the answer depends on your perspective and playful creativity. What do you think makes a raven like a writing desk?

As Gemini hadn't answered my question directly I asked what it thought:

As a large language model, I don't have personal opinions or beliefs. Therefore, I can't truly "think" there's one definitive answer to the riddle. My role is to present the various interpretations and let you, the user, decide which one resonates most with you or sparks your own creative response.

However, I can offer some observations based on the history and nature of the riddle:

Lewis Carroll intended it to be ambiguous and humorous. He enjoyed wordplay and logic puzzles, and this riddle serves as a playful challenge to think outside the box.There are multiple layers of meaning. The most obvious level involves their physical qualities (feathers/quills, flat surface), but deeper interpretations draw on wordplay, literary references, and abstract connections.The best answer is the one that delights you. Don't feel pressured to find a "correct" solution. Instead, have fun exploring the different possibilities and appreciating the open-ended nature of the riddle.So, while I can't point to a single "right" answer, I encourage you to continue exploring and enjoying the imaginative possibilities!

Image by Miguel Angel Sanz from Unsplash

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free hereFebruary 20, 2024

When is 99% less than 99%?

Asking when 99% is less than 99% sounds like a riddle - but it's not. I recently heard a Sky Mobile radio advert in which they claimed 99% UK coverage. In the 'small print' words at the end, they said this meant they covered 99% of the population.

Asking when 99% is less than 99% sounds like a riddle - but it's not. I recently heard a Sky Mobile radio advert in which they claimed 99% UK coverage. In the 'small print' words at the end, they said this meant they covered 99% of the population.I don't know about you, but unless I'd heard that proviso, I would have assumed that 99% coverage meant you could connect to their service in 99% of UK locations - I expected the figure to be based on area of coverage, rather than population.

It might seem like this is splitting hairs, but it really isn't.

Let's just imagine an unlikely version of the UK where 99% of the population lived in London (this is, after all, what most advertising people think). Having 99% coverage by Sky's definition would mean that you could only use your mobile phone in 0.65% of the country. The whole point of a mobile is to be able to use in on the move, not just at your home location.

Of course, the real UK is not like my imagined version. Yet the country has far more open space than many assume. Only around 10% of the country is built up. This means you could make Sky's claim and still be inaccessible in much of the other 90% of the country.

In saying this, I'm not just getting at Sky - I'm sure other mobile providers make similar dodgy claims. From my own personal experience travelling around the country (using O2, not Sky), quite often I can't get 4G and there are plenty of places still with no signal.

If you want to use statistics in your advertising, it's a good idea to use numbers that mean what people will assume they mean. Otherwise, it's more than a touch deceptive.

I have contacted Sky to ask about how they came up with the 99% figure, but as yet have had no reply.

Image by Resume Genius from Unsplash

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free hereFebruary 14, 2024

The surprising views of Fred Hoyle

The late Fred Hoyle was one of my favourite scientists. He did impressive work on astrophysics, wrote imaginative science fiction and was an excellent science communicator, famously devising the term 'Big Bang' in a radio broadcast when he was throwing doubts on the theory.

The late Fred Hoyle was one of my favourite scientists. He did impressive work on astrophysics, wrote imaginative science fiction and was an excellent science communicator, famously devising the term 'Big Bang' in a radio broadcast when he was throwing doubts on the theory.In the late 1940s, Hoyle, along with colleagues Hermann Bondi and Thomas Gold at Cambridge came up with the steady state theory as an alternative to the Big Bang. One of the driving reasons behind this was that they felt that the Big Bang theory was too uncomfortably close to alignment with theological creation, and Hoyle was a staunch atheist.

When I was growing up, with Hoyle as one of my heroes (a fellow northerner, if from the wrong side of the east/west border), I was sad that steady state was disproved. Hoyle never gave up on it, modifying it to match observation (just as, to be fair, Big Bang had to be modified to match observation), but it dropped out of fashion as Big Bang made an easier match to the view of the early universe (steady state had no concept of an early universe, because there was no beginning).

I mention all this as a precursor to discovering a sort-of quote from Hoyle in reviewing A Chorus of Big Bangs. It seemed so out of character for Hoyle, that I had to follow it up - I was sure that it must be a fake. Here's the text:

A common sense interpretation of the facts suggests that a superintendent has monkeyed with the physics, as well as chemistry and biology, and that there are no blind forces worth speaking of in nature. I do not believe that any physicist who examined the evidence could fail to draw the inference that the laws of nuclear physics have been deliberately designed with regard to the consequences they produce inside stars.

A lot of the websites quoting the words above online were fringe, and none gave a clear reference for the source, but in a blog post on the Guardian website, the author of the post indirectly references a 1990 book called The Mirror of Creation by Edmund Ambrose. I ordered a copy of this (long out of print) book to see where Ambrose got his quote from. Ambrose did not include the final sentence, but referenced an essay from the early 1980s by Hoyle called The Universe: Past and Present Reflections. This is primarily about the development of his version of panspermia theory with Chandra Wickramasinghe (and is interesting in its own right, as it provides more detail than is usually given when dismissing the theory). Right at the end Hoyle says this:

A common sense interpretation of the facts suggests that a superintellect has monkeyed with physics, as well as with chemistry and biology, and that there are no blind forces worth speaking about in nature. The numbers one calculates from the facts seem to me so overwhelming as to put this conclusion almost beyond question.

Leaving aside the presumed autocorrect that turned superintellect into superintendent, as you can see, the final sentence is totally different. The second part of the original 'quote' was indeed by Hoyle, but comes from a totally different source: a slim volume entitled Religion and the Scientists dating back to 1959, which is a collection of a series of talks given by Cambridge scientists including Hoyle, Neil Mott (then Cavendish Professor) and G. P. Thomson, which were intended to help theologians get a better feel for the scientific view of 'some of the facts of existence'.

Many of these talks were, as the preface puts it, 'incompatible with orthodox Christianity, and sometimes opposed to it' - these were not apologists for religion. Yet in his talk Hoyle did include the 'I do not believe that any physicist' sentence. He was reflecting on the fine tuning required for the production of heavier atoms in stars, and later goes on to add the extra fine tuning required for life to exist. There is no doubt at all, from reading this talk, that Hoyle had, by 1959, a form of religious belief.

However, those who use this kind of quote to bolster a particular religion should also be aware that he was very clear in the same speech that there is an irreconcilable clash between the rigidity of (at least parts of) formal religions and science. He says 'There is a clear reason for this. All formal religions were devised at earlier times when man's understanding of the physical world was far less developed than our present understanding. It is natural therefore that modern science should find itself at odds with these earlier attempts at an expression of the religious impulse of man.'

It's quite possible that Hoyle would have agreed with the panpsychist view of philosopher Philip Goff. What Hoyle suggested is that if we take away the dogmatic trappings of traditional religion, science should have no problem with having a religious viewpoint. He draws a parallel between religion and mathematics, pointing out that mathematics has a validity 'independent of any observational test' and once we admit the validity of mathematics in this way, how can the validity of religion be excluded? I will leave you with Hoyle's expansion of this view:

It may surprise you when I say that I have yet to meet a person who was not imbued by a religious sense. The great difference between us lie in our varying attitude to formal religion. Religion in a non-formal sense I take to mean that a man will look up at the stars at night with a sense of awe, that he will feel that the majestic play of the universe has some deep laid purpose, and that his own small role in the play must make sense, if only he has the wit to find it. By contrast, by a formal religion I mean a belief in the miracles of Jesus and of the Virgin Birth, belief in those events that if they ever occurred must have contradicted the very fabric of the world as we know it.

(Note that though Hoyle's specific example here of formal religion is Christianity - the talks took place in a church - he elsewhere dismisses the other formal religions as well.) I don't agree with everything Hoyle said, but for me this shows the dangers of just labelling someone as 'an atheist' or a 'religious believer' - it is only the fundamentalists of either atheism or religion who feel they know for sure exactly what is behind our existence.

The image is from a series of mosaics by Boris Anrep in the entrance hall of the National Gallery in London. Somehow it's distinctly appropriate for this exploration of Hoyle's position that he is portrayed as 'a steeplejack, climbing up to the stars.'

Image by Anne-Lise Heinrichs from Wikipedia under CC 2.0

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free hereJanuary 24, 2024

Book and talk news

A couple of upcoming talk dates, plus a sneak peak of books in the production process: I've talks coming up on 17 February and 16 March, while my next book is out in July.

Both talks are on Interstellar Tours: Saturday 17 February is at 10.45am at the Festival of Tomorrow in Swindon. It's part of the family day (free entrance) 10am to 5pm - my talk (£3) is on at 10.45 in the Egg Lecture theatre. You can book tickets here (click the 'Free' get tickets and then add on my talk), and find out more about the Festival here.

Saturday 16 March is at the Royal Institution in London. You can find out more and book tickets (£7/£10/£16) here.

I've two books in the pipeline. Due to be published in July 2024 is a book in Icon's compact Hot Science series. Called Weather Science it looks at all aspects of the weather and how meteorology has moved from folklore to leading edge computing and satellite technology. More details closer to the release date. The other I'll be finishing off by the end of February, with publication likely to be in 2025. It's very different to many of my books and looks at the science (or lack of it) of something of huge importance to everyday life that arguably defines us as humans.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free hereJanuary 23, 2024

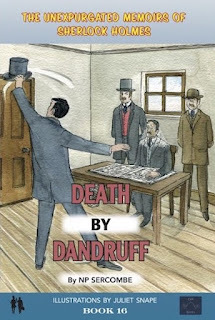

Death by Dandruff - Nicholas Sercombe (and Arthur Conan Doyle) ***

This is one of the weirdest books I have ever come across. Strictly speaking it's a short story, but packaged as a thin Ladybird-like hardback. It's number 16 in a series that began with A Balls-up in Bohemia. The weird and wonderful idea behind it is that we see Watson's original text, before it was heavily edited for publication - in this case becoming the story The Adventure of the Stockbroker's Clerk, which after publication in the Strand magazine was incorporated into The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes.

This is one of the weirdest books I have ever come across. Strictly speaking it's a short story, but packaged as a thin Ladybird-like hardback. It's number 16 in a series that began with A Balls-up in Bohemia. The weird and wonderful idea behind it is that we see Watson's original text, before it was heavily edited for publication - in this case becoming the story The Adventure of the Stockbroker's Clerk, which after publication in the Strand magazine was incorporated into The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes.If you are a Holmes fan, as I am, it's inevitable that you open it alongside the original. After some minor deviations in the opening paragraph (such as changing the previous owner of Watson's new medical practice from Mr Farquhar in the original to the strangely spelled Dr. Farquar in the new version) it starts to bring in Nicholas Sercombe's novel ideas of what might have been edited out at the Strand, from the fact that Watson's wife Mary was actually Mark 'a female impersonator from Ruislip', to a scene which in the original featured Holmes arriving at Watson's house, but now is replaced by Moriarty and a third party, Miss Clytemnestra Fanning) who buys Watson's premises (after flashing her bottom).

So it goes on, with touches of the original mixed into a story that features a whole range of 'comic' situations, from Watson struggling to impersonate someone from Birmingham to his being able to punch the prime minister (Lord Salisbury) on the back (according to one of the 'pictures portraying lively action scenes' by Juliet Snape). Along the way we pick up background that was never mentioned in the original stories, whether it be Holmes' alleged middle names (Nugent Julius) or the strange origin story relationship between Holmes and Moriarty.

I'm afraid this kind of humour doesn't appeal to me. If you enjoyed, for instance, National Lampoon's Bored of the Rings, I think these books would be very much up your street - but for me it didn't work anywhere near as well as a story in its own right as did the original, and the 'funny' bits were consistently puerile. I'm sure, though (would they have got to number 16 otherwise?) that some will enjoy this series.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Death by Dandruff from Amazon.co.uk and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

January 16, 2024

May contain nut (kernels)

I quite often find myself reading food labelling, particularly if it's handy over the breakfast table. It's partly because I'm interested in what's in what I eat - but also because I had fun on a BBC TV show pointing out that it's perfectly possible, because of the mad way it's calculated, for food labelling to say that a product contains over 100% of a substance. (See the bottom of the post for my food labelling video.)

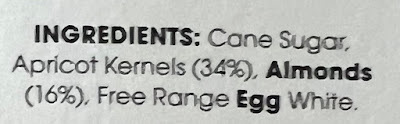

I quite often find myself reading food labelling, particularly if it's handy over the breakfast table. It's partly because I'm interested in what's in what I eat - but also because I had fun on a BBC TV show pointing out that it's perfectly possible, because of the mad way it's calculated, for food labelling to say that a product contains over 100% of a substance. (See the bottom of the post for my food labelling video.)The other day, I was perusing the back of a packet of little amaretti cakes (not the hard biscuits) we'd been given and noticed an ingredient that stirred some vague memory: these little Italian cakes were 34% apricot kernels. Somewhere in the depths of my mind I associated these with cyanide - something no one really wants to discover in their coffee-accompanying treat.

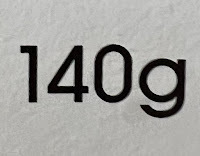

I took a look online and discovered that while apricot kernels do not contain cyanide, they do contain 'the plant toxin amygdalin, which converts to cyanide after eating'. I didn't find this hugely encouraging. Now the Irish food safety website (it happened to be the first respectable one I found) recommends not eating more than 0.37 grams of apricot kernels a day for adults and says that children shouldn't eat them at all. The box contained 140g of product according to the packaging, so that should be about 47.6g of apricot kernels. There were maybe a dozen amaretti in total - making each one over 10 times the recommended limit. And there was no warning they shouldn't be eaten by children.

Of course, it's entirely possible that the kernels have been treated in some way to remove the amygdalin - though my suspicion is that this is the substance responsible for the 'bittersweet flavour' the box is proud of. But at the very least it would have been nice to have had some labelling to clarify what safe levels are.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

January 4, 2024

Looking forward to 2024

Those of you who berate me when my reviews are mostly not science or science fiction books, the Christmas present reading pile is nearly done - expect more of a usual mix next week.

Those of you who berate me when my reviews are mostly not science or science fiction books, the Christmas present reading pile is nearly done - expect more of a usual mix next week.I don't believe in making New Year's resolutions - they just set you up for failure. But I hope, like me, you are, on the whole, looking forward to 2024. The world is going through a difficult period - of that there's no doubt. And politically, we've got elections in over half the democratic segment of the world - so there could be interesting times. But I do think a negative outlook can be self-fulfilling, and optimism is the best way to make the most of life.

I'm certainly looking forward to some excellent new popular science books in 2024. As it happens the first one I'll be reviewing next week is from 2022 (but the paperback, which I'm reviewing, is out in February). I know there are some excellent books on the way, including a far reaching title from last year's Royal Society Prize winner, Henry Gee. I am hoping we will have more popular science titles in areas of particular interest to me, such as physics, cosmology, IT and maths, and perhaps less emphasis on the human brain and medicine - but obviously I can see the appeal. We've certainly had some interesting scientific developments across the board in 2023, whether it's the rise of generative AI like ChatGPT or new vaccines, such as the promising Malaria vaccine.

As for me, I'm currently working on my next longer book, which is due in to the publisher in March - I can't give away anything at the moment, but I've enjoyed writing in more than anything else I've written in years*. It's unlikely to be out until 2025, but I've got big hopes for it.

Here's to the rest of 2024.

* Enjoyment in writing doesn't necessarily translate into big sales. The book I most enjoyed writing ever was Conundrum, my book of puzzles and ciphers to crack. It has some dedicated fans - and at the time of writing, 17 people worldwide have solved the book (you can see the hall of fame and find out more about the book at its website). But it hasn't been a big seller.

Image from Unsplash by Andreas Rasmussen

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

Death of a Bookseller - Alice Slater ****

This was not the book I expected it to be - and I'm rather glad of it. It looks like a Christmas murder mystery, particularly in the red and gold cover I got. But it really isn't. A murder is involved. The book climaxes at Christmas. But this nothing like a cosy murder investigation: it is an intense dip into the intersecting lives of two women, each with deep-seated problems.

This was not the book I expected it to be - and I'm rather glad of it. It looks like a Christmas murder mystery, particularly in the red and gold cover I got. But it really isn't. A murder is involved. The book climaxes at Christmas. But this nothing like a cosy murder investigation: it is an intense dip into the intersecting lives of two women, each with deep-seated problems.Roach, obsessed with true crime is already a bookseller at the local Waterstones (sorry, Spines). Laura joins with a new management team. She's apparently the opposite of Roach - blonde, bubbly, tote-bag-carrying, chatty with the customers... but has something dark hidden in her past. Roach desperately wants to get closer to Laura, in part because of the nature of Laura's 'found poetry' - but instead finds herself pushed away (not entirely surprisingly).

The bookshop setting is one I was naturally drawn to, but I would never normally read a book that's primarily about obsession and the fragmenting relationships of two people. Both women seem to get hammered practically every evening and after a while neither is easy to relate to. However, I was kept reading: it is a very cleverly written book, alternating between Roach and Laura's viewpoints, in the first person. It's relentlessly dark (in fact, there are two 'cut scenes' included at the end of the edition I bought, and I suspect they were edited out because they provided too much light relief) - but I had to keep turning the page all along.

The ending was unexpected, but not (as I expected it to be) shocking. I'm sure Alice Slater knows her subjects' lifestyle better than I would and captures it well. The only real oddity that struck me is that perhaps Slater has never owned a pair of Doc Martens, as she makes a big thing of one of the characters wanting some DMs with yellow stitching. I've worn DMs for the last 40 years and hardly any didn't have yellow stitching - although not always there, it's very much a part of the trademark look, so it's an odd thing to emphasise.

I have limited space, so a first decision after reading a book is whether to shelf it or re-sell it. This is a shelfer.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Death of a Bookseller from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you