Brian Clegg's Blog, page 156

October 14, 2011

What has happened to nursing?

[image error]

Come back Florence, all is forgivenThere has been quite a lot of fuss in the news this week about terrible care taking place in hospitals. I was listening to the Health Secretary on the radio and he was saying that poor care from nurses was down to bad leadership. I'm not sure this is the whole of the answer.

When they had a vox pop on the programme a little earlier, the daughter of a badly-cared-for patient was saying that she repeatedly asked for help from nurses to do basic things, but 'they didn't care - they seemed to feel it was beneath them'. And I'd suggest that this is a contributory factor.

Once upon a time, nurses did basic medical checks - but their primary role was nursing. Caring for people. In the last 30 years, their training has become increasingly medicalized (if there is such a word). They are trained to be and to think of themselves more as doctors lite. The inevitable result is that some nurses feel that it really isn't their problem to worry about a patient's basic physical state, they are there to deal with the medical side.

Don't get me wrong. Many, many nurses do a wonderful job. But I would suggest that those who do are managing to do this despite their training, rather than as a result of it, and there should be just as much focus on this as on failings in leadership.

Picture from Wikipedia

When they had a vox pop on the programme a little earlier, the daughter of a badly-cared-for patient was saying that she repeatedly asked for help from nurses to do basic things, but 'they didn't care - they seemed to feel it was beneath them'. And I'd suggest that this is a contributory factor.

Once upon a time, nurses did basic medical checks - but their primary role was nursing. Caring for people. In the last 30 years, their training has become increasingly medicalized (if there is such a word). They are trained to be and to think of themselves more as doctors lite. The inevitable result is that some nurses feel that it really isn't their problem to worry about a patient's basic physical state, they are there to deal with the medical side.

Don't get me wrong. Many, many nurses do a wonderful job. But I would suggest that those who do are managing to do this despite their training, rather than as a result of it, and there should be just as much focus on this as on failings in leadership.

Picture from Wikipedia

Published on October 14, 2011 00:57

October 13, 2011

The compounds made to kill

It's Royal Society of Chemistry podcast time again.

It's Royal Society of Chemistry podcast time again.My grandfather served in the first world war, lying about his age in his eagerness to sign up and fight for his country. In later years, he told many tales of warfare in Belgium. But nothing held the same horror for him as the gas attacks. Though he never experienced them first hand, they remained the ultimate bogeymen of that terrible conflict.

The sulfur mustards were the final, most terrible agents of chemical warfare deployed in the first world war - and they are the subject of today's podcast. The evil compounds that most of us know inaccurately but potently as mustard gas.

Published on October 13, 2011 00:56

October 11, 2011

The Litmus test for science in fiction

I love both popular science and science fiction, and like the idea of lablit, fiction with a science setting that isn't science fiction per se. But there is another crossover between science and writing that ought to be great but that never quite makes it - this is fiction that has the intention of putting across a serious scientific message.

I love both popular science and science fiction, and like the idea of lablit, fiction with a science setting that isn't science fiction per se. But there is another crossover between science and writing that ought to be great but that never quite makes it - this is fiction that has the intention of putting across a serious scientific message.Every now and then we get a book for review at www.popularscience.co.uk that attempts to do just this. A good example was the novel Pythagoras' Revenge by Arturo Sangalli. The idea was excellent and Sangalli nearly achieved the desired result. It genuinely did put across the maths (in this case) in a more approachable way. Unfortunately the fiction itself wasn't great. And this seems to be the challenge that most attempts at doing this fall down on. Either the fiction is poor, the science isn't very good, or the whole thing comes across as too worthy and dull. It is clearly very difficult to do well.

So I had mixed feelings when I got a copy of Litmus , a collection of short stories illustrating science themes. You can see what I thought of the book by following the link to the review, but in summary it was another worthy failure. Many of the stories were either not very good, or so full of their own artistry that they obscured the science. The book tried to get around this by following each story with a little explanation of the science and historical context, but this made things worse. It broke the flow of the stories and poured on a rather condescending dullness.

I don't like to admit defeat in anything that is being used to popularize science. But I am beginning to think that using fiction to get across the message is doomed to failure because you have two such contradictory aims. Something rather similar seems to happen on TV show QI when someone on the panel who is into science starts to expound a little on a science subject. The other panellists typically start acting bored and the whole thing falls flat.

Don't get me wrong, there are lots of ways to get people more aware and informed about science that can entertain and inspire. But I'm not sure writing fiction with a science context is one of them. Science in fiction is fine - but as soon as it becomes 'education about science in fiction' it falls flat.

Published on October 11, 2011 23:46

The Fox and the hounds

UK news is currently full of the story of Defence Secretary Liam Fox. Doctor Fox, as he is all too frequently called (wasn't that the name of a DJ?), is in the middle of a storm of accusation because of allowing a close friend, Adam Werritty to act as if he were an official advisor and accompany Fox on a range of official visits. This doesn't look too good, especially as it's possible Werritty could benefit financially from it - something that he may not have done, but certainly could have done.

UK news is currently full of the story of Defence Secretary Liam Fox. Doctor Fox, as he is all too frequently called (wasn't that the name of a DJ?), is in the middle of a storm of accusation because of allowing a close friend, Adam Werritty to act as if he were an official advisor and accompany Fox on a range of official visits. This doesn't look too good, especially as it's possible Werritty could benefit financially from it - something that he may not have done, but certainly could have done.What I find fascinating is the way that those who speak up on Fox's behalf - bluff Tories one and all - are producing the most irrelevent arguments. They seem to fall into two camps:

Liam Fox is a nice guy - well, yes, so are quite a lot criminals. This doesn't signify anything.They are saying this about Liam Fox because they want to do him downLet's look at that second accusation in a bit more detail. Notice that it is an argument about motive, not substance. Just transfer the argument to a mass murderer for a moment to show how useless it is. Imagine someone has very clearly committed a mass murder. There is absolutely solid evidence that he did it. No question. But his defence team argue that we should ignore it, because the people who are putting forward the evidence don't like the murderer. Yes, that's a fine argument, folks. That will get him off.

The facts seem to be that Werritty presented himself as an offical advisor, including having a business card saying this, embossed with the trademark portcullis of the government. There is good evidence that Werritty accompanied Fox on 18 of his 48 overseas trips (not spin from his enemies, data from the Ministry of Defence). It really doesn't matter why people are saying this, the facts are clear.

This was unacceptable behaviour for someone in Liam Fox's position and he must have known that. This makes it rather pathetic when those defending Fox say 'I'm sure he has learned from this.' A 15-year-old would know this isn't a good idea. If he needed to learn from this, he shouldn't be doing a serious political job. Send him back to the surgery.

I genuinely don't want the government destablized. I think it is bad for the country in the current difficult climate, and it's a shame. But this is a fox that should be given to hounds and dispatched immediately.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on October 11, 2011 00:42

October 10, 2011

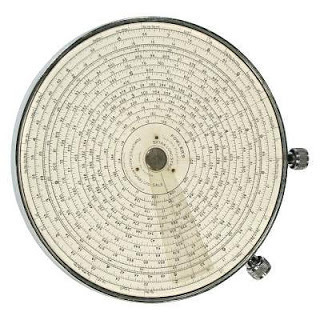

The joy of analogue

I was half-listening to the BBC radio show

The Museum of Curiosity

over the weekend when something caught my ear. One of the guests, popular maths writer Alex Bellos, was talking about a mechanical pocket calculator from the 1940s. One of the other guests, Jimmy Carr commented that it went out of fashion when 'everything went digital' (or words to that effect). I was expecting Bellos to jump on him from a great height, but instead he said that, yes, soon after computers took over.

Not only is Jimmy Carr's statement inherently wrong, but the whole discussion is an example of (probably unintentional) historical revisionism, missing out on a fascinating stage in the development of computing technology.

My dad's circular slide ruleCarr's comment was so wrong because a mechanical calculator is digital. We tend to equate digital and electronic - but forget why we do this. It's because (digital) mechanical calculators were mostly ousted in science and engineering by analogue calculators (also mechanical) which in turn were replaced by (digital) electronic calculators. To take the story straight from mechanical to electronic is poor history to say the least.

My dad's circular slide ruleCarr's comment was so wrong because a mechanical calculator is digital. We tend to equate digital and electronic - but forget why we do this. It's because (digital) mechanical calculators were mostly ousted in science and engineering by analogue calculators (also mechanical) which in turn were replaced by (digital) electronic calculators. To take the story straight from mechanical to electronic is poor history to say the least.

The analogue revolution that Carr and Bellos ignored is the slide rule, making fast complex calculations easy. We tend to look down on analogue solutions because they are approximate - though they can be made as accurate as you like - but all we're really saying there is that they're natural. Digital may be the reality at the quantum level, but the world we experience (including many aspects of the way our brains work) is analogue.

I used to have a beautiful circular slide rule that was my father's. The advantage of the circular version is that in a compact device, less than 10 centimetres across, you had the equivalent of a straight slide rule much too long to use. And it was lovely to twiddle and do those calculations. I confess I sold it, because I'm not much of a collector, and it is certainly obsolete, but it doesn't stop it being a wonderful device.

I'm all in favour of using humorous programmes to get across science and history - but do make sure you get your facts right, guys.

Not only is Jimmy Carr's statement inherently wrong, but the whole discussion is an example of (probably unintentional) historical revisionism, missing out on a fascinating stage in the development of computing technology.

My dad's circular slide ruleCarr's comment was so wrong because a mechanical calculator is digital. We tend to equate digital and electronic - but forget why we do this. It's because (digital) mechanical calculators were mostly ousted in science and engineering by analogue calculators (also mechanical) which in turn were replaced by (digital) electronic calculators. To take the story straight from mechanical to electronic is poor history to say the least.

My dad's circular slide ruleCarr's comment was so wrong because a mechanical calculator is digital. We tend to equate digital and electronic - but forget why we do this. It's because (digital) mechanical calculators were mostly ousted in science and engineering by analogue calculators (also mechanical) which in turn were replaced by (digital) electronic calculators. To take the story straight from mechanical to electronic is poor history to say the least.The analogue revolution that Carr and Bellos ignored is the slide rule, making fast complex calculations easy. We tend to look down on analogue solutions because they are approximate - though they can be made as accurate as you like - but all we're really saying there is that they're natural. Digital may be the reality at the quantum level, but the world we experience (including many aspects of the way our brains work) is analogue.

I used to have a beautiful circular slide rule that was my father's. The advantage of the circular version is that in a compact device, less than 10 centimetres across, you had the equivalent of a straight slide rule much too long to use. And it was lovely to twiddle and do those calculations. I confess I sold it, because I'm not much of a collector, and it is certainly obsolete, but it doesn't stop it being a wonderful device.

I'm all in favour of using humorous programmes to get across science and history - but do make sure you get your facts right, guys.

Published on October 10, 2011 00:28

October 7, 2011

Ball of Confusion

For UK TV viewers of a certain age, Johnny Ball is something of a legend. Sadly I never watched him as a child, but for a whole generation he made finding out stuff about how the world works fun. And I can say from personal experience that (unlike many famous people) he's a really nice guy.

For UK TV viewers of a certain age, Johnny Ball is something of a legend. Sadly I never watched him as a child, but for a whole generation he made finding out stuff about how the world works fun. And I can say from personal experience that (unlike many famous people) he's a really nice guy.This is a book of 'puzzles, problems and perplexing posers' - just the thing for a Friday. They vary from classic 'if two cats could kill three mice in...' type problems, through logic problems to tricky little numbers that rely on very careful reading of the question.

Inevitably, if you've been about a bit like me, you will have come across a few of them before. And there are bound to be some you just can't be bothered with. But as long as you get any enjoyment out of these types of brain teasers you are bound to find something that is truly entertaining. And, of course, Johnny Ball presents them with his characteristic charm. Just occasionally I found his 'funny' intros to the problems better suited to a ten-year-old's taste than mine, but mostly they are fun and keep the book from being literally a list of puzzles.

The only criticism I have is that when you are setting puzzles, some of which involve trickery and misleading wording, you have to be absolutely spot on with the wording of your challenge, or it can be legitimately cheated. Here's an example where Johnny got it wrong:

Find a fluted glass and a large and a small coin; say a 5p and a 10p. Place both coins in the glass, so the larger coin lies flat and over the small coin. Your impossible task: can you get the small coin out, without touching either coin.The solution given is relatively complex and not something you may think of (and it wouldn't work with the kind of flutes I have). But the book misses the obvious one. Pick up the glass and tip the coins out. You have got the smaller coin out without touching either coin. There's nothing in the problem statement that says that the larger coin has to stay in the glass.

This is a rarity, though, and many of the mental challenges and puzzles (mostly they don't involve something physical like this) are genuinely entertaining. If you have friends and relations who enjoy a bit of head-scratching fun, this is the present for them. See at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com - also on Kindle at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

Published on October 07, 2011 01:12

October 6, 2011

A farewell to Jobs

It's very sad news that Steve Jobs has died. There will be plenty of pieces posted saying how wonderful he was, how visionary and how unique. And that's fine. He did some amazing things, and in the last few years has transformed Apple from a quirky personal computer manufacturer into the ultimate designer of personal electronic accessories. But I want to consider one point that is unlikely to be brought up in the eulogies that rightly will follow his death. How much he owed Apple's current success to John Sculley.

It's very sad news that Steve Jobs has died. There will be plenty of pieces posted saying how wonderful he was, how visionary and how unique. And that's fine. He did some amazing things, and in the last few years has transformed Apple from a quirky personal computer manufacturer into the ultimate designer of personal electronic accessories. But I want to consider one point that is unlikely to be brought up in the eulogies that rightly will follow his death. How much he owed Apple's current success to John Sculley.In 1985 - just one year after the Mac was launched - Jobs was forced out of Apple, as the company headed for crisis. The man behind this was Sculley, brought in from Pepsi to make Apple a more commercial operation. At the time Jobs was pushing Apple towards producing high end UNIX technical workstations. He would set up the not-particularly-successful NEXT computer company to produce the machine he thought Apple should be making. (The only time I've ever seen Jobs do his black turtleneck spiel on stage was at the launch of NEXT in the UK.) NEXT wasn't a total flop, but it wasn't a burning success either, and it was when the company was bought by Apple that Jobs came back to the fold in 1996.

Under Sculley, Apple was to produce one product and one vision that for me are absolutely the seeds of the iPhone and the iPad. Sculley's pet product was the Newton, a touchscreen personal digital assistant. It had problems, particularly with its text recognition, but it was a truly interesting product. Even better, though, was the 1987 concept video, Knowledge Navigator. This, without doubt, set the direction that would eventually produce the iPad. At the time I was blown away - and I still think the concept video is great (see below).

Now I suspect this period is going to be almost airbrushed out of Apple's history, but it's crucial. The really innovative ideas came when Jobs wasn't there, though I don't want to underplay the vast contribution he made in adding the detail and crucially the design orientation that made iPhone and iPad what they are today. I very much want to celebrate Steve Jobs' wonderful work in the history of ICT - but lets not forget the roots of that work either.

Published on October 06, 2011 00:35

October 5, 2011

Don't blame TV for the cult of celebrity

Not the picture in question. But

Not the picture in question. Buta good one - whoever painted it.We often hear moaning about how TV has exposed us to the cult of celebrity, where people are valued simply for being famous, not for what they produce or perform. I think it's very short sighted to blame TV - the real culprit is the traditional arts, which no doubt would snootily blame TV, but actually started this cult of celebrity long before Logie Baird came on the scene.

Take a point of example. We have recently heard that a 'fake' picture allegedly by Leonardo da Vinci could be real. If this is the case, the picture, which last sold for £14,000 'could be worth millions.' Now either this is a great work of art or it isn't. If it's great, it should be worth a lot of money. If it's not, it shouldn't. Why does it matter whose name is attached to it? That's just a matter of celebrity, as much as paying money for the rights to Kerry Katona's latest exploits. Who made the picture is irrelevent to whether or not it's a great work of art.

It's the same with music. Whether a piece is by Mozart (say) or one of his less famous contemporaries, it shouldn't make any difference - merely how good it is. Anything else is just idiocy riding on the back of celebrity.

Note this doesn't say there's anything wrong with expecting something interesting from paintings by Leonardo because he's a great artist. That's just like wanting to read the latest book by your favourite author. It makes sense. But when it comes to the value of an individual painting that should stand alone. After all, even the best author can produce a turkey, and the best book you've ever read could be by a new author.

Behold, the cult of celebrity in its worst possible form - and it's the art world that keeps it going.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on October 05, 2011 00:06

October 4, 2011

Date me, I can explain general relativity

I was browsing through the pages of that excellent magazine, New Scientist, when I noticed this advert for 'New Scientist Connect'. Yes, now scientists have their own dating site where lovers of geeks and nerds can browse for a hot postdoc (with or without marshmallows).

I was browsing through the pages of that excellent magazine, New Scientist, when I noticed this advert for 'New Scientist Connect'. Yes, now scientists have their own dating site where lovers of geeks and nerds can browse for a hot postdoc (with or without marshmallows).I first became aware of this kind of thing a while ago when Classic FM started advertising a service called something like classic duets. (Geddit? Duets, classical music? Oh, for goodness sake.) I suspect they got too many complaints from people who thought it was a site to listen to, well, classical duets, not a dating site. But now it goes from strength to strength as Classic FM Romance.(It's interesting that the URL format of the two sites is similar. Surely it couldn't be the same company behind them?!)

I suppose the concept has some merits. You would know you had an interest in common. Or maybe not. Perhaps on the 'opposites attract' theory, New Scientist Connect is mostly browsed by beauty therapists and professional footballers.

It does make me wonder whether there also sites for, say, traffic wardens to get together (after all, who else could love them), or the Dawkins GeneSplice site where aggressive atheists can spend their time slagging off everyone else. And for that matter I also wonder who designed this ad, and really thought that someone dressed as Biggles, running across snow carrying a toy plane typified an attractive scientist...

Published on October 04, 2011 00:25

October 3, 2011

Get your act together, Volkswagen

The naming of cars is an important and serious business. The sort of thing that pushes Jeremy Clarkson and his Top Gear buddies to the realms of ecstasy. Which is why I wonder about the sanity of those in charge at car manufacturer Volkswagen. It seems they name their models by picking nouns that look interesting out of a foreign language (i.e. English) dictionary.

The naming of cars is an important and serious business. The sort of thing that pushes Jeremy Clarkson and his Top Gear buddies to the realms of ecstasy. Which is why I wonder about the sanity of those in charge at car manufacturer Volkswagen. It seems they name their models by picking nouns that look interesting out of a foreign language (i.e. English) dictionary.They are so random in their selection.

For example, there's:

the one named after a dog-related wild animal, (Fox/Lupo), the pair named after hit-ball-with-stick games (Polo/Golf), the one named after a wind (Sirocco), the one named after a spelling mistake (Passat), the one named after an Essex girl (Sharan) and a couple that are so boring I can't even remember what they're called.

Come on, Volkswagen. You can do better than this. A five-year-old can do better than this...

Image from Wikipedia

Published on October 03, 2011 00:22