Brian Clegg's Blog, page 25

September 26, 2022

The Capture (Series 1) - BBC iPlayer

Though hugely flawed in some ways, The Capture proved to be one of the most gripping TV shows I’ve watched in a while, thanks to the regular invocation of clever twists that make the viewer think ‘How is that possible?’

Though hugely flawed in some ways, The Capture proved to be one of the most gripping TV shows I’ve watched in a while, thanks to the regular invocation of clever twists that make the viewer think ‘How is that possible?’The focus throughout is video surveillance - specifically how, and if, it can be misleading or tampered with to make something that didn’t really happen appear to be the case.

I’m specifically reviewing the first series - I haven’t started the second yet, but will give it its own review. The focus initially is a soldier accused of killing someone without the need to do so in Afghanistan. (This was why I didn’t watch the series when it first came out as I tend to avoid military topics.) But although the soldier in question becomes a major character throughout, it isn’t really his story.

It was clever and did more than entertain, really giving the viewer an opportunity to think about the underlying moral dilemma (the details will have to wait until after the spoiler alert). The other main character, a fast-tracked female DI, temporarily assigned from SO15 (counter terrorism) to murder was well filled by Holiday Grainger, emphasising both the initial resentment of her by the team and her sometimes ruthless urge to get on, as the negative balance to her positive unwillingness to let go, even when ordered to do so.

— SPOILER ALERT —

The most unlikely thing for me was that to make the whole thing work required not one, but two conspiracies. Firstly there was the CIA/MI5/SO15 grouping referred to as Correction and secondly a more unlikely grouping of human rights activists, who decide to use the mechanism employed by Correction to show that a terrorist’s conviction relied on fake video evidence. This did make for some intriguing twists, but seemed one conspiracy too far.

The Correction aspect was also overplayed in the sense that the CIA outfit particularly seemed far too effective. But this is where the moral dilemma card is played, even if it seems highly unlikely in practice. The Correction involves faking video evidence to convict terrorists when the security services know that they are guilty, but this knowledge is based on data that can’t be used in court. The details seemed a little hazy - it would only be theoretically justifiable if things like communication intercepts were always inadmissible, which I didn’t think was the case.

The other other-the-top aspect was the way that the security services reacted to the fake video produced (with extremely unlikely skill) by the human rights activists - the botched and extreme measures taken seemed logically unnecessary. I’d also say that the soldier’s introduction to the activists was like something out of Poliakoff’s excellent fantasy The Tribe - it was far too slick for the reality of who they were.

So, a lot of stretching of likeliness is needed to make this work - but it's worth it, both for the gripping drama and the possibility that something like this might be done, whether by security services or rogue states.

September 24, 2022

The mnemonic trap

As an author, it's not uncommon to get emails or letters correcting something in one of my books. Sometimes these corrections are useful, at other times, the correspondent misses the point. But I recently had one from Ronja Denzler that was not only correct, but also highlighted something really interesting about mnemonics.

These phrases to remember something can be genuinely handy - most of us can still recall those for rainbow colours or planets (often still incorporating Pluto) from school, while I distinctly remember a woman called Ivy Watts from my physics class. But the most elegant are the numerical mnemonics, where the numbers of letters in each word represents a digit. This form reaches its zenith in the mnemonics for pi - so much so that the art of producing these has its own, distinctly tortured, name of 'piphology'.

When I wrote Introducing Infinity - a graphic guide in collaboration with the excellent illustrator Oliver Pugh, I asked if he could use a fuller version of the mnemonic I vague recalled from school. The bit I could remember was 'Now I, even I, would celebrate in rhymes unapt the immortal Syracusian...' - Oliver extended this further in the image below:

It was this illustration that Ronja wrote to complain about - because the thirteenth decimal place is incorrect. The reason for this is that the rhyme was originally dreamed up by one Adam C. Orr of Chicago. Being American, his idea of how to spell 'rivalled' was not the same as the British one. Although Oliver is entirely accurate in his illustration that rivalled should have 8 letters, unfortunately the US spelling only has 7 - and that's what the 13th decimal place should have been.

The moral of this story is that if you are designing a numerical mnemonic in English, make sure that you don't use any words such as rivalled, or travelled, or colour, or labour where US and British spellings deviate - otherwise, someone is bound to be misled.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here Find out more about Introducing Infinity here.

September 20, 2022

Don't knock our queues

Photo courtesy of Eva AmsenI was somewhat bemused by a thought piece by James O'Malley suggesting that we've got it all wrong with our pride in Britain's ability to put on a good queue, as exemplified by the queue for the late Queen's lying in state.

Photo courtesy of Eva AmsenI was somewhat bemused by a thought piece by James O'Malley suggesting that we've got it all wrong with our pride in Britain's ability to put on a good queue, as exemplified by the queue for the late Queen's lying in state.O'Malley tells us 'It’s also a completely bonkers, wrong-headed way to think about Britain. When we see a queue, we should feel embarrassed.' The reason for this, he suggests, is that a queue means that we aren't being dealt with efficiently - our precious time is being wasted. He goes on to say 'when we see a queue we should want to celebrate it - we should want to eliminate it.'

As someone who worked in Operational Research, and who has done quite a lot of work with queuing theory, I would respectfully suggest that he is wrong. Not in the suggestion that we should want to minimise queuing - of course no one wants to waste their time. But outside of a fantasy world we have to consider the reality that lay behind Macmillan's response to being ask what the greatest challenges faced by statesmen were: 'Events, dear boy, events.'

There were always be circumstances where resources are limited compared to demand - and in such circumstances, the queue in its multiple guises is often the fairest way to deal with the situation. The British pride in its queue forming is not in the need for the queue, but rather dealing with circumstances where there is that resource/demand imbalance in a good tempered and orderly way.

It's absolutely true that we should engineer queues out of existence if possible. I recently sang the praises of Marks and Spencer's new system where I can scan things, put them straight into my shopping bag and pay on my phone as I walk towards the door without ever going near a till. That's a queue successfully deleted. But you can't always do that engineering. In some circumstances this is because it takes time to engineer solutions and we may need the queue now. In others, the cost of the resources to remove the queue is greater than the cost of the queuing time.

That's not to say that O'Malley is wrong in saying that virtual queues such as booking systems have a lot of value - but it's naive to suggest that one could have been set up for the scale and nature of queue required in the Queen's lying in state. O'Malley suggests we could have modified the Covid jab booking system. But this would have involved attempting to apply a massively multiple queue, multiple server system to a single queue, dual server physical reality. The only way a booking system would have significantly changed things is if it was used to drastically reduce the number of people who could attend, which isn't really helping.

So, accepting there are circumstances where queues are needed, I think it's perfectly acceptable to be proud of a culture where, when they are required, they form naturally and easily, rather than in some countries, where any pretence of queuing rapidly collapses into a free-for-all. I was particularly impressed a few years ago when I went to a row of three cashpoints with a good few people waiting. I'm not sure how O'Malley would envisage dealing with this kind of queue. Putting at least ten cashpoints in each location, most of which would spend all their time idle? Making people book ahead to withdraw cash? But the queuers were a beautiful sight to see. Instead of forming separate queues behind each cashpoint, with no guidance they formed a single queue, multiple server formation, providing the fairest division of waiting time. I was truly proud of them.

September 6, 2022

When will the Green Party go green on energy?

I despair of the Green Party here in the UK. They are still pumping out the same old knee-jerk reaction of the ex-hippies to nuclear power. It's as if they didn't realise how important climate change was. It's not just one item in a green buffet of options. It's the big one.

I despair of the Green Party here in the UK. They are still pumping out the same old knee-jerk reaction of the ex-hippies to nuclear power. It's as if they didn't realise how important climate change was. It's not just one item in a green buffet of options. It's the big one. We need massive change to deal with the climate emergency - and that includes moving to a mix of energy generation that doesn't produce greenhouse gasses. Yes, there must be plenty of wind and solar (and ideally wave/tide too) - but we also need generation that doesn't depend on the weather and sun - for which nuclear is the obvious option.

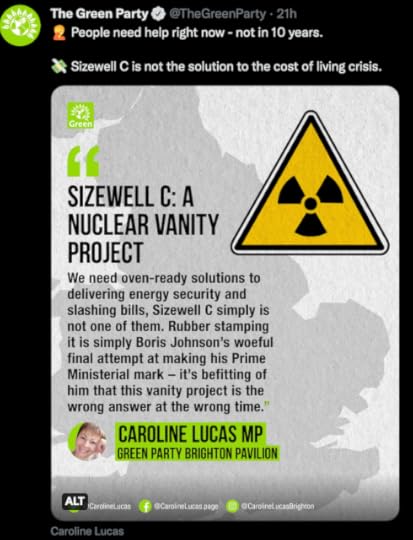

Caroline Lucas of the Green Party put out this tweet on 1 September 2022, and I don't know where to start.

Of course, a new nuclear plant is not 'the solution to the cost of living crisis' (though nuclear energy is a lot cheaper than the current price of gas). It's part of the long-term solution we desperately need to put in place to complete the move to zero carbon energy generation. There is no magic energy source that will deliver energy security with zero carbon instantly. We need to build the appropriate infrastructure. Of course we need immediate action to slash bills - and that isn't about building new power stations - but that's no excuse for putting of building essential infrastructure to give us energy security in the future. To make matters even worse - Caroline Lucas was saying exactly the same thing a decade ago - and from that perspective we definitely did need help in 10 years time.

Unless the Greens get their heads out of the sand, they remain a barrier to coping with climate change. They are as green as a company trying to get us to use more fossil fuels and should be avoided at all costs.

This has been a Green Heretic production.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

September 5, 2022

The Gap in the Curtain - John Buchan ***

John Buchan is best known for his thriller The 39 Steps, filmed melodramatically by Alfred Hitchcock in 1935. The Gap in the Curtain is another period piece, first published in 1932, but it is anything but a conventional thriller. It's sometimes presented as science fiction, but it would more reasonably be described as fantasy: although the events it covers are supposedly triggered by the work of a scientist, the mechanism is pure fantasy.

John Buchan is best known for his thriller The 39 Steps, filmed melodramatically by Alfred Hitchcock in 1935. The Gap in the Curtain is another period piece, first published in 1932, but it is anything but a conventional thriller. It's sometimes presented as science fiction, but it would more reasonably be described as fantasy: although the events it covers are supposedly triggered by the work of a scientist, the mechanism is pure fantasy.We begin at a country house party, where a random selection of toffs are encouraged to take part in an experiment by the mysterious Professor Moe. By obsessing over a particular section of the Times newspaper for a while (plus the administration of a mystery drug), seven participants are set up to have a second's glance at a small section of the newspaper from one year in the future. In practice, two of the experimental subjects, including the narrator, don't undertake the final part, so five people are given a brief glimpse of the future. Some study a section of the paper relevant to their role - an MP, for example, finds out something about the future government - others seem to have picked part of the newspaper pretty much at random. The rest of the book then covers the subsequent year five times, once for the experience of each subject.

So far, so good - a nice, high concept plot. Although I like the Hitchcock film, I've never read any Buchan before - I found his style, frankly, rather clunky. The country house setting is like P. G. Wodehouse without the humour, and the first section progresses distinctly slowly. Things get rather better with the five individual sections. In each case, although the predicted text from the Times is correct, the outcome is different to the one that the participant expects. I did particularly enjoy the MP's section - there was a strange similarity with 2022 British politics, with the country facing dire economic straits and some MPs who were clearly only in it for what they could get for themselves. Although the people were fictional, it was interesting to get a feel for what early 1930s politics was like as a Labour government struggled with the problems of the day.

For amusement's sake, the cover of my

For amusement's sake, the cover of my 1962 edition (no idea how I got itI did find it hard to warm to any of the characters - I love Wodehouse, and his lightweight protagonists are simply fun. Here, the entitled gentry, who make up pretty well all of the characters in the book, often feel repulsive to the modern viewpoint. I don't know if this was Buchan's intention, or whether he felt this was what upright British folk should be like. But this aspect wasn't too much of a problem as it really wasn't necessary to engage with the people - it's the plot that dominates.

All in all, though never a thrilling read (and the denouement of the last section was a distinct let-down), the period setting and the underlying idea made it well worth the read.

-- SPOILER ALERT --

I do want to moan about a couple of aspects of the plot, so if you don't want a spoiler, don't read further.

Two of the five active participants in the experiment focus on the obituaries section of the paper - and both see their own death listed. This requires a ridiculous pile-up of coincidences. Firstly, why would they choose to look at this part of the paper anyway? Everyone else looked at a topic that interested them. Why didn't they look at a sporting page or whatever? More to the point, what are the chances that, purely accidentally, both of them were predicted to die the day before the day the paper was published? There was no suggestion that the experiment was the cause of their deaths - they simply had a glimpse through the titular 'gap in the curtain'.

One of the two death cases was handled quite well. The person effectively scared himself to death, with a little twist where he avoided the way he 'should have' died, but still died. The second, though, involved the subject escaping his fate. That wasn't a bad idea - but the way that Buchan made this happen was to have an obscure relative die on the predicted date, whose name was the same, whose regiment had been incorrectly reported and whose birthdate had been misheard and put in wrong. A whole pile of unlikeliness. How much more interesting it could have been if someone (the narrator, for example) had sent a fake death notice the Times (inevitably with various obstacles to this happening). The piece would have appeared, but wouldn't really be true. Managed well, it would have been a far better ending than the pathetic list of coincidences and accidents Buchan uses. Moan over.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can order The Gap in the Curtain at Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

September 4, 2022

Americast vs The News Agents

Interesting things are afoot in the world of UK news podcasts. The former presenters of the BBC's best podcast, Americast, have shifted to rival Global and have gone from a weekly-ish podcast to weekdaily one as The News Agents. Meanwhile, the BBC has just broadcast the first of a rebooted Americast. And the good news is, both are excellent.

Interesting things are afoot in the world of UK news podcasts. The former presenters of the BBC's best podcast, Americast, have shifted to rival Global and have gone from a weekly-ish podcast to weekdaily one as The News Agents. Meanwhile, the BBC has just broadcast the first of a rebooted Americast. And the good news is, both are excellent.Let's start with Americast. There was a real danger that when the original leads Emily Maitlis and Jon Sopel left that we would end up with a pale imitation, as happened when the Top Gear team departed. (Admittedly that was under more dubious circumstances - I don't think either Maitlis or Sopel punched anyone.) However, rather than replace the originals with amateurs, the BBC has been clever here. They've kept the solid, American third leg of the programme, Anthony Zurcher, and replaced the duo with a pair of BBC big hitters, Justin Webb and Sarah Smith.

Going on the first episode (which was confusingly launched on the Newscast podcast), Americast is in good hands. I think it's fair to say that Webb and Smith are yet to have the easy chemistry of Maitlis and Sopel - but the show had the mix of solid content and lightness of touch we've come to expect from Americast. I'll be sticking with it.

Meanwhile, we have Maitliss and Sopel, joined by Lewis Goodall (like Maitlis, from the BBC Newsnight TV show) as The News Agents. We've now had a few of their shows to listen to and they're coming along well. At the moment they are overdoing the cutesiness - referring to 'News Agents HQ' and giving everyone nicknames, which is mildly irritating, but the old Maitlis and Sopel magic is there and it's shaping up well.

Meanwhile, we have Maitliss and Sopel, joined by Lewis Goodall (like Maitlis, from the BBC Newsnight TV show) as The News Agents. We've now had a few of their shows to listen to and they're coming along well. At the moment they are overdoing the cutesiness - referring to 'News Agents HQ' and giving everyone nicknames, which is mildly irritating, but the old Maitlis and Sopel magic is there and it's shaping up well. One thing is certainly true: the podcast beats the BBC's equivalent, Newscast hands down. Newscast seems to have gone a bit downmarket having lost some of the political big hitters like Laura Kuenssberg and feels rather too much like a podcast version of the One Show on an off day. Main anchor Adam Fleming is reliable, and Kuenssberg's replacement Chris Mason not bad (though isn't so interesting), but the content isn't well focussed and rarely asks the searching questions. There's no doubt that The News Agents is the better of the two.

All in all, my podcast schedule is having a great week!

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

August 30, 2022

The strange case of the French bottom of erotic principle

Way back in the early 90s, I attended a lecture by the Austrian-born computing pioneer Hermann Hauser, one of the pair behind Acorn computers, the maker of the BBC micro. In his talk, Hauser was describing the difficulty of computers understanding a language like English, illustrating this with a pair of phrases:

Way back in the early 90s, I attended a lecture by the Austrian-born computing pioneer Hermann Hauser, one of the pair behind Acorn computers, the maker of the BBC micro. In his talk, Hauser was describing the difficulty of computers understanding a language like English, illustrating this with a pair of phrases:Time flies like an arrow

Fruit flies like an apple

Hauser pointed our the difficulties of machine translation, as long as computers had no understanding of the underlying language and context. For a computer, it would be natural to interpret those phrases the same way. As it happens, machine translation has moved on by taking a totally different direction - it still doesn't understand language, but by using vast amounts of data, it has become quite strong on context.

A few years after this lecture, I received an email which brought Hauser's point back to me. At the time, machine translation was in its infancy. The email was distinctly interesting thanks to the strange case of the French bottom of erotic principle.

My oldest web address belongs to my creativity training company - it's www.cul.co.uk. At the time I got it, I was rather proud to have a 3 letter URL, which matches the initials of the company and thought no more about it. I was probably vaguely aware that 'cul' means bottom in French, as in 'cul-de-sac' but otherwise it was just a web address. Imagine my surprise, then, to receive this email:

Please allow the transfer, I use a mechanical software because I very English of cannot.

On the 14éme, in the porque one, I slap a search with the form returned www.cul.co.uk. Then to say to you, cul is a bad French word? It average rest-on the flesh of the rectum of anybody. Since this, cannot think you the need to want the nation French with the arrangement of creative. Thus I give to help in all fraternity, to think please for the change.

Familiar the most pleasant

Henri.

Though a little suspicious that this was a wind up, I replied and got the equally entertaining response:

Brian Estimable

The considerable thanks of you answer. You software for the language is improved much that my kind of shareware - where is to be found.

It is now possible to include/understand the reason of the bad word. Internet is problematic with much pornographique available if the button supported on danger pressed. I do not require to see the French bottom of erotic principle of Alta-Vista that www.cul.co.uk accidental gives. Families with the small particular person in danger.

Since the text of slit into type is vanilla, umlauf nonvisible. Is very the easy error in time forwards with the European of the trade unions. Better to speak friends than the argument of the football which recent English have.

pleasantries

Henri

Delightful indeed. (The bit about the 'umlauf' is because I pointed out that the CUL logo, as illustrated, had an umlaut on the U.) Of course, Henri could be un artiste des pissoirs, but I like to think he was a genuine Frenchman with a concern for my moral welfare.

Familiar the most pleasant,

Brian

August 22, 2022

Interzone 292-293 review

I review SF books on the Popular Science website, but this is a review of a science fiction magazine, which seems a sufficiently different prospect to find its way onto my blog instead.

I review SF books on the Popular Science website, but this is a review of a science fiction magazine, which seems a sufficiently different prospect to find its way onto my blog instead.Interzone is the classic British science fiction magazine dating back to 1982 - I last read it many moons ago when David Pringle was the editor and it was formatted like a magazine - now it's in more of a glossy digest format. As it happens, this double edition marks the change of an era, as it is the last from current editor Andy Cox, who is handing over to Gareth Jelley.

Apparently, the Science Fiction Writers of America don't consider Interzone a professional magazine due to the unusually low rates they pay (just 1.5 cents per word) and the circulation - I think it's a shame. Frankly, they ought to pay more and it's sad that this magazine seems to be looked down on by the SF establishment as it is practically the only such magazine we have in the UK.

As a reader primarily of SF books, I have mixed feelings about Interzone's current incarnation. The format feels odd. Each story has a title illustration, which as a book reader makes it feel a bit childish, but worse, it's a full colour magazine and presumably to make this worthwhile, after the illustration, each story is set in pages with a coloured border reflecting that illustration - to me, this just gets in the way of the words and makes it feel a bit like the design of a 'My Secret Confessions Diary 1982'.

However, it's the content that really matters. This is a double edition - Jelley is apparently going back to bi-monthly single issues, combined with an online magazine Interzone Digital. Apart from an SF news roundup and film review, the content of the magazine amounts to 11 stories - which seems thin for a double edition. Part of the problem was that too many of them were long: more of a mix would have been better. [Updated 22 August (see comments)] I am told that the next two editions editions will feature more stories for a single edition, and will have more shorter stories. [End of update]

For me, there was one standout, a handful of okay stories and a couple of definite misses. The one that jumped out to me was Alexander Glass's The Soul Doctor. This was fairly long, but easily carried the length, rather than feeling padded out. Oddly, for a contribution to a set of SF stories, this was in some ways closer to what used to be called Science Fantasy, on two levels. One is that it is based on the Many Worlds hypothesis, an untestable interpretation of quantum theory that some physicists regard as fantasy. The second is that even if Many Worlds holds, in the story, a character can switch at will between alternate universes, which seems scientifically impossible, especially as he seems to be able to combine this with time travel as he is able somehow to sample different alternate universes until he finds one with the outcome he wants - but Many Worlds doesn't stop the passage of time (in fact it's inherently tied to it). Despite this, what we have here is a really good story, instantly engaging and beautifully developed.

Interestingly, after reading this magazine, the next thing I happened to do was to re-read New Writing in SF 20, edited by John Carnell in 1972. This was part of a series of paperback books featuring new SF stories. The stories in there are, to be honest, of higher quality (I suspect it paid more). It's not that they were more staid and less experimental. The very first story, for example, Conversational Mode by Grahame Leman, takes the form of a conversation between a patient and a psychiatric computer that at times verges on stream of consciousness, but is a real hit in the gut. So there's a touch of 'could do better' for Interzone - I have no doubt that there are even more great SF stories out there now.

My other concern is for the future. In his introductory editorial, Jelley tells us his focus is 'fantastika' which apparently is made up of 'horror and fantasy and sf and all the subgenera that subtend like fruit from that triad'. This pretentious wording is Jelley quoting eminent SF expert John Clute, who should know what he is talking about - but to be honest, when I read a magazine like Interzone I want it to stick to science fiction. Of course this can have a horror flavour (or for that matter crime or romance or other genre), and I'll stretch to the Science Fantasy of The Soul Doctor, but I don't want pure horror or fantasy.

Overall, I've mixed feelings about Interzone. I bought a six edition subscription, and I will read the remainder that I receive, but I'm not sure I'll go back to it. I'm really glad it's there, because we ought to be able to support (plural) SF magazines in the UK, but there wasn't enough content that really worked for me.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

August 14, 2022

Review: The Generation Killer - Adam Simcox

Urban fantasy, which brings fantasy elements into the everyday world, is far more interesting than the totally imaginary setting of a classic fantasy, because the clash between familiar life and weirdness provides brilliant opportunities to stretch the imagination. Of late, some of the best urban fantasies have incorporated a police procedural element - most notably the Rivers of London series. But Adam Simcox inverts the whole approach.

Urban fantasy, which brings fantasy elements into the everyday world, is far more interesting than the totally imaginary setting of a classic fantasy, because the clash between familiar life and weirdness provides brilliant opportunities to stretch the imagination. Of late, some of the best urban fantasies have incorporated a police procedural element - most notably the Rivers of London series. But Adam Simcox inverts the whole approach. Standard urban fantasy/police procedural crossovers feature real world police coping with fantasy-driven problems. Simcox gives us a refreshing new approach in dead detectives who deal with crimes defeating the mundane police. This is linked into an afterlife that seems loosely based on the Catholic triad of hell, purgatory and heaven, with the main fantasy setting being the Pen, described as purgatory, but in reality distinctly hellish. It’s from here that dead cop Joe Lazarus sets out, making a dangerous transition to our world, which the dead refer to as 'the soil'.

Simcox gives us an impressively layered fantasy realm with its own mind-boggling problems (introduced in the first novel in the series, The Dying Squad). The Pen is run by a 16-year-old (dead) Warden Daisy-May, who struggles with keeping in control as she is new to the job, had little in the way of induction training and is dealing with a realm of rebellious souls and half-souled 'dispossessed'.

The fantasy location of the Pen is interesting (though a reader who hasn’t read the first book might find it hard to get their head around). But the book’s real strength is when crimes are investigated in the real world - this happens in two parallel storylines, with Joe Lazarus pursuing the Generation Killer of the title in a very dark and gloomy Manchester, while the Duchess (Daisy May’s predecessor as Warden) is trying to stop her sister from wreaking havoc in Tokyo. Each of these storylines is strong enough to support a book on their own, and whenever the action moves back to the afterlife, I was impatient to return to the soil.

Simcox has come up with such a rich piece of world building that it can sometimes be tricky to follow the logic - good fantasy (unlike magical realism) has to be internally consistent. It seemed a bit odd, for example, that people in the afterlife could be killed - did they end up in the afterafterlife? Was it turtles all the way down? But in the real world action parts, this feels less of an issue.

The Generation Killer is an original, gripping and gut-wrenching approach to the urban fantasy genre. It works on its own, but I’d recommend reading The Dying Squad first.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can order The Generation Killer at Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

August 12, 2022

Review: The Undeclared War (Channel 4)

With apologies to the late T. S. Eliot, this is the way the series ends: not with a bang but a whimper.

With apologies to the late T. S. Eliot, this is the way the series ends: not with a bang but a whimper.I held out a lot of hope for The Undeclared War because it was set primarily in GCHQ - always interesting - and it centred on computing and cyber attacks. As someone with a programming background I was sure this would appeal to me - and those core aspects really did, which is why I stuck with it through six episodes. But on the whole it was shambolic, poorly plotted and ended with an unforgivable double deus ex machina.

** SPOILER WARNING - I WILL DISCUSS DETAILS OF THE FINAL EPISODE **

Admittedly, from the start I had some doubts. Recognising that just watching people doing stuff on screens wasn't the most thrilling TV, it was decided instead to use a very heavy-handed visual simile. So when our heroine, Saara (who is basically Famous Five material, as she is student who defeats the baddies when the experienced adults can't), was searching through lots of code, we saw a version of her, equipped with an IT utility belt, wandering past vast stacks of boxes. When she had to break into some hidden code... she had to break into a locked location. And, for no obvious reason, when things were difficult to understand, she stared into a big glass structure, apparently left over from the set of The Cube - I was expecting Philip Schofield to turn up any moment.

Then there were the characters - often so two-dimensional and stereotyped that it was wince-making. The two best characters - Mark Rylance's ageing code breaker and Kerry Godliman's cynical British journalist working for a Russian propaganda TV channel to produce fake news - were only effectively bit players, but they were far more interesting than the leads. And so much just seemed to happen randomly, such as a Russian hacker's journalist girlfriend being propelled from being not much more than an anti-Putin blogger in Russia to the main frontline presenter in the UK on said TV channel.

Still, things staggered along with just enough to keep me interested until we got to that final episode.

Up to this point, the Russian state cyber-baddies had been running rings round plucky GCHQ and poor old head of operations Simon Pegg kept being hauled in front of COBRA (are the Cabinet Office Briefing Rooms really located in such a concrete bunker of a place?) to explain why once again GCHQ had messed up. On the whole this seemed to be because the Russians could do magic, because what they were achieving certainly isn't physically possible.

In the final episode, GCHQ discovers what we've known for several episodes - that the Russians have hacked GCHQ's internal CCTV. Simon Pegg's character is confused, because the CCTV is air gapped. Which means it can't be hacked without physical intervention. Just to be clear, an air gap means that the system isn't connected to the internet, nor is any system it is connected to. You can only hack it by physically connecting to it - and there was no suggestion that this had been done.

But that's a minor detail. In deus ex machina event 1, Saara hauls in her secret weapon, a savant mathematician (another student Famous Five wannabe) who can crack anything. The whole plot centres on some code used to attack the BT network. This code had a secret second payload, which was much nastier that Saara discovered. (No one explains why the code was still running at this point.) But Saara realises there is a third payload which had enabled the software to pass on secrets from first the NSA and now GCHQ. (This means the Americans don't trust us anymore.) She can't find that payload, so brings in her tame mathematician. He tells her that some apparently junk data is really encrypted code, but he has an algorithm that will decode it so they can see it. And it turns out that when a few episodes ago Saara ran the malicious code in a sandbox, the third level payload started emailing out all the secrets. It was all her fault (sort of).

It's hard to know where to start with what's wrong with this. Encrypted code can't run because the software that runs the code can't read it. So how was it supposed to be running? If there had been a decryption algorithm also in the code, then that would have been found. For that matter, a sandbox is a secure place to run code that might cause damage. So sandboxes, particularly somewhere like GCHQ, are air gapped (see above). Anyone who's ever worked with computer viruses and worms knows you work on them using an unnetworked computer. So even if the encrypted code had somehow managed to magically run, it could neither access NSA and GCHQ data (which wouldn't have been in the sandbox) nor could it email the secrets out.

Having found the code, computer whizz Saara can't kill it, but the maths whizz does with a quick flurry on the keyboard. Phew. But the Russians are now escalating the cyber attacks to full scale war. Enter deus ex machina 2, the Russian hacker we met earlier, who coincidentally was in the same class as Saara at a UK college the previous year. At the last moment, he sends all the Russian code to the UK so they can win back the trust of the Americans and triumph. He also sends them a video of his FSB training, where the lecturer triumphantly describes exactly how they have pulled the wool over the eyes of thick old GCHQ. Bravely, our hacker sits at a desk in the FSB offices, translating this lecture as a baddy homes in on him. Yet he was still able to send all that code. Did it not occur to him that GCHQ might have one or two people who spoke Russian and he didn't need to provide a live translation, he could have just forwarded the video as well?

And then the programme just stops, as if the writer got bored. Wow. I kept thinking 'It's going to get better. They'll have a clever ending planned.' They didn't.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here