Steven Erikson's Blog, page 5

April 28, 2016

Fall of Light (Excerpt)

ONE

STEPPING OUT FROM THE TENT, RENARR FACED THE BRIGHT morning light, and did not blink. Behind her, on the other side of the canvas wall, the men and women were rising from their furs, voicing bitter complaints at the damp chill, snapping at the children to hurry with the hot, spiced wine. Within the tent, the air had been thick with the fug of lovemaking, the rank sweat of the soldiers now gone, the metallic bite of the oils with which the soldiers honed weapons and worked to keep leathe...

Fall of Light (2016)

Bantam Press (UK)

Tor Books (US)

Steven Erikson returns to the Malazan world with the second book in a dark and revelatory new epic fantasy trilogy, one that takes place a millennium before the events in his New York Times bestselling Malazan Book of the Fallen. Fall of Light continues to tell the tragic story of the downfall of an ancient realm, a story begun in the critically acclaimed Forge of Darkness.

It is a bitter winter and civil war is ravaging Kurald Galain. Urusander’s...

The Fiends of Nightmaria (2016)

Containing twenty-plus pieces of artwork from David Gentry, The Fiends of Nightmaria is the new Bauchelain and Korbal Broach novella from Steven Erikson. From a review of the novella:

The king is dead, long live King Bauchelain the First, crowned by the newly en-cassocked Grand Bishop Korbal Broach. Both are, of course, ably assisted in the running of the Kingdom of Farrog by their slowly unravelling manservant, Emancipor Reese.

However, tensions are mounting between Farrog and the neighbou...

February 10, 2015

On Authorial Intent

Years ago, when I first began my study of writing, I was both fortunate and cursed to land, right off the bat, a spectacularly good workshop teacher for fiction. My initiation into the craft of writing was through a teacher and mentor who knew precisely what he was doing, and by that I mean, he was conscious of everything he wrote. That was the fortunate part, as he awakened in me the same appreciation of the power of storytelling, and all that was possible provided you’d given serious though...

The Discussion of Writing

Years ago, when I first began my study of writing, I was both fortunate and cursed to land, right off the bat, a spectacularly good workshop teacher for fiction. My initiation into the craft of writing was through a teacher and mentor who knew precisely what he was doing, and by that I mean, he was conscious of everything he wrote. That was the fortunate part, as he awakened in me the same appreciation of the power of storytelling, and all that was possible provided you’d given serious thought to the effect your words would have, and could have, to a reader. But, alas, it was also a curse. I hesitate to say this, since it is bound to be misconstrued as arrogant (when the truth is, it’s more desperate and frustrated than arrogant). You see, what made it a curse was that, thanks to that first teacher, I proceeded on the assumption that all writers knew precisely what they were doing: with every word, every sentence, every paragraph and every story.

Well, that was long ago, and a lot of muddy water has passed under the bridge since then. I have been privileged to find myself in the company of countless published authors: well-regarded, bestselling, highly popular authors. In each instance, it was indeed a privilege, and to this day I often feel something of an imposter in their midst. That said, I have also been witness, every now and then, to another side of that whole persona of ‘popular, highly-regarded’ authordom, which for lack of a better phrase, I will call the Blank Wall.

Before I explain that, I should point out that I am well aware that some writers feel that there is a value in maintaining a certain mystique when it comes to the writing process, as if to explain too much will somehow degrade the wonder (and, perchance, tarnish that aura of genius we all like to maintain before our fans, hah hah). But that always struck me as a rather narrow perch, and a dubious one at that. There is very little that is worthy of mystery to telling a story, and very little of the day-in day-out grind of being a fiction writer invites elevation to superhuman status, and besides, one of the most extraordinary wonders of writing lies precisely in what is possible, and rather than hiding one’s cards (as if we published authors possess some secret code of success, jealously guarding our muse-given talent), I for one have always delighted in sharing the bones, meat and skin of narrative, particularly to aspiring writers and anyone else who might be interested.

Back to the Blank Wall. I ran face-first into that wall rather early on, in the company of that highbrow institution of exclusivity known as CanLit (an amorphous Canadian entity of ‘serious’ literature as promulgated primarily by the Canada Council, writing departments at universities, the Globe and Mail, provincial granting agencies, and CBC Radio). In effect, that mystique and aura was a facade presented not only to the public, but also, strangely enough, quickly and almost instinctively raised up between writers, with some underlying notion of competition feeding it, one presumes. No one seemed open to discussions on the bones, muscle and skin of writing. Granted, I was perhaps hopelessly clumsy in seeking such conversations in the midst of public venues of mutual congratulation and the maintenance of personae, but even my tentative suggestions inviting such dialogue at some later date was met again and again with that Blank Wall.

Granted, it may just be that I’m odious or something, and that each author intellectually ran for the hills at the mere suggestion of engaging me in a conversation. But, oddly enough, odious only to authors, as the rest of my social life seems healthy enough.

Over the years I have taken to attending the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts, a scholarly conference in which authors and writers of the genre are invited to sit in on papers presented on their work; and to, on occasion, be part of panels of authors/creators taking questions from the scholars. Being part of those panels can be both exhilarating and profoundly frustrating, as every now and then I sat beside fellow authors intent on maintaining that mystique, that high, blank, impenetrable wall. Some go so far as to respond to every question by holding up their latest book and pointing out that it’s available in the book-room. Now, this may come across as a bit cruel (and who knows how many enemies I’m making here among my compatriots), but it strikes me that, of all venues and of all potential audiences, isn’t the ICFA one inviting something more than a sales-pitch? We sit at our long table facing a room full of academics and scholars, and spend the hour obscuring the glass between us and them, presumably to maintain that aura of distinction. Of course, I may be even more uncharitable in this, knowing as I do that many authors are shy, often awkward, and besides, it is simpler to fall back on the cliches of ‘why we write’ (‘I write only for myself! But thanks for reading me!’), than it is to strip things back to expose the inner workings.

But, for all that my comments here invite excoriation, another potentially more egregious thought occurs to me, and it goes back to the blessing and the curse of my first workshop teacher, and it’s this: maybe many authors don’t want to talk about the gristle of writing 1 not because they’re interested in maintaining a mystique, but because they don’t think about those things, or, at best, they can’t articulate their reasons behind writing what they write.

Before I continue digging this hole of mine, allow me to say that I have been fortunate over the years to find fellow writers more than eager to engage in discussions of the kind I’m advocating here. In each circumstance, I am privileged to discover writers who know precisely what they’re up to, and even more wonderful, they’re prepared to talk about it!

They may not know it, but they are my lifeline, and I’ll not embarrass them by naming names here — you know who you are and what you mean to me, since when it comes to that, I’m anything but coy. Also, not all of them are writers: some are scholars who take an interest in what lies behind a narrative or an invented world. Others would call themselves, quite simply and humbly, fans. My lifeline, everyone of you.

But let’s get back to what’s driving me crazy, shall we? It’s probably time to explain what has inspired me to write this essay. Well, I’ve been reading certain blogs and exchanges, here in Goodreads and elsewhere, that raise issues directly relating to authorial intent; and some authors are facing and responding to a most cogent series of questions from critics/fans/readers. These questions highlight (not always in a complimentary fashion) some of the possible assumptions carried over from our world into an invented one.

As questions, most worthwhile indeed. They need to be asked, and no work available to the public can make any claim to immunity against them, just as no author can contemptuously dismiss them (regardless of whether the questions arise from someone who has read their work or not — the nature of the question itself remains legitimate. It is its relevance that bears thinking about, not on specific grounds, but on general ones, as I will explain shortly).

Often, the discussion that follows, whether involving the author or just fans and advocates and detractors of the argument in question, can quickly bog down into semantic disputes and personal attacks intended to undermine the authority behind any statement being made. This kind of divisiveness may be inevitable, as unfortunate as it is, as the original question gets left behind.

Unlike times past, this modern age makes a commodity of both an artist’s works and the artist in question; whereas pre-internet authors could feel open to both advancing or rejecting the cult of the persona. These days, there is a pressure on writers to present to the world more than just their published works, but also their own personae. This has the effect of blurring the distinction between the two, particularly in the eyes of fans (and be assured, there is a profound distinction there, though sometimes neither as profound nor as distinct as one would hope: specifically, when an author writes fiction to advance his or her politics, agenda, world-view and a host of other prejudices, in a manner that reveals their contempt for contrary opinions).

In short, we’re in an age where author and the work are both fair game, both open to direct challenge by critics and readers. This is the case of playing with fire and getting occasionally burned.

I am no longer convinced that every published author has given full consideration to the host of assumptions they carry into their created world. Well. There. I said it. I will not get into specific examples here, though it wouldn’t take long to assemble a fair list of ‘you-had-no-idea-what-you-were-really-saying-here-did-you?’ films, novels, and the like. That is, I can only assume they didn’t know what they were saying, unless I choose to believe that certain creators of mass media out there have no compunction about encouraging terrorism, perpetuating bigotry, misogyny, rape and hate crimes; and are equally happy advocating revenge as the primary recourse to justice.

So, what has all this to do with the Fantasy genre? Plenty, because it’s a genre that invites you (as a writer), even demands you, to invent something new, something other. But in that process of invention (of, say, an entire other world), there is the risk that certain assumptions or behaviors or attitudes from this world can slip in, unquestioned, unchallenged, unexplored. And when that happens, why, it’s fair game for anyone — anyone — to throw down the gauntlet in challenge. And when it becomes evident, in an author’s direct response, that certain elements were not thought-through, not thought-out, that author then faces the choice of mea culpa or launching into a full defense of their position, which in turn further blurs the distinction between author and the author’s work in question. This is messy, but I find myself lacking sympathy: we are, after all, in an age of communication that expects the creators be present, engaged, and prepared to stand behind their words. It’s not all fun and games and ego-massaging, after all. There’s a price to pay for notoriety.

If, into this invented fantasy world, certain assumptions about gender roles, skin colour, sexual preference, etc, are carried ad hoc from our world, then it is incumbent that they be challenged. Why? Because it matters. Because, every time shit like that is carried over, an underlying assumption is made: that such assumptions adhere to some Natural Law, wherein arguments in defense of such choices devolve into falsehood (‘history shows it was always that way’ [no, it doesn't], and ‘in a barbaric world a patriarchy is given’ [no, it isn't], or, ‘in a post-apocalyptic world where remnants of hi-tech is akin to magic, men will still rule and dominate every social hierarchy’ [say what? That doesn't even make sense!]). The Natural Law argument is a fallacy; more to the point, the Fantasy genre is the perfect venue in which to utterly dismantle those assumptions, to offer alternative realities and thereby challenge the so-called givens of the human condition.

Cheers

Steven Erikson

* * *

What do I mean by ‘gristle,’ ‘meat and bones,’ etc? Well, imagine you are a published author, and you are asked ‘Why did you craft that sentence the way you did? What effect were you looking for in that sequence of events? Why did you carry those particular assumptions from our world into the one you invented for your stories? Ah, but that last question … a hint to where I am headed with this lengthy discourse here, perhaps?

November 20, 2014

Willful Child (2014)

Bantam Press (UK)

Tor Books (US)

From the New York Times Bestselling author Steven Erikson comes a new science fiction novel of devil-may-care, near calamitous and downright chaotic adventures through the infinite vastness of interstellar space.

These are the voyages of the starship A.S.F. Willful Child. Its ongoing mission: to seek out strange new worlds on which to plant the Terran flag, to subjugate and if necessary obliterate new life-forms, to boldly blow the…

And so we join the not-terribly-bright but exceedingly cock-sure Captain Hadrian Sawback and his motley crew on board the Starship Willful Child for a series of devil-may-care, near-calamitous and downright chaotic adventures through ‘the infinite vastness of interstellar space.’

The New York Times bestselling author of the acclaimed Malazan Book of the Fallen sequence has taken his lifelong passion for Star Trek and transformed it into a smart, inventive, and hugely entertaining spoof on the whole mankind-exploring-space-for-the-good-of-all-species-but-trashing-stuff-with-a-lot-of-high-tech-gadgets-along-the-way, overblown adventure. The result is an SF novel that deftly parodies the genre while also paying fond homage to it.

Bantam Press (UK) • London (2014) • hard cover • ISBN: 978-0-5930-7307-0

Tor Books (US) • New York (2014) • hard cover • ISBN: 978-0-7653-7489-9

August 1, 2012

Forge of Darkness (Excerpt)

PRELUDE

. . . so you have found me and would know the tale. When a poet speaks of truth to another poet, what hope has truth? Let me ask this, then. Does one find memory in invention? Or will you find invention in memory? Which bows in servitude before the other? Will the measure of greatness be weighed solely in the details? Perhaps so, if details make up the full weft of the world, if themes are nothing more than the composite of lists perfectly ordered and unerringly rendered; and if I should kneel before invention, as if it were memory made perfect.

Do I look like a man who would kneel?

Bantam Press (UK)

Tor Books (US)

There are no singular tales. Nothing that stands alone is worth looking at. You and me, we know this. We could fill a thousand scrolls recounting the lives of those who believe they are each both beginning and end, those who fit the totality of the universe into small wooden boxes which they then tuck under one arm – you have seen them marching past, I’m sure. They have somewhere to go, and wherever that place is, why, it needs them, and failing their dramatic arrival it would surely cease to exist.

Is my laughter cynical? Derisive? Do I sigh and remind myself yet again that truths are like seeds hidden in the ground, and should you tend to them who may say what wild life will spring into view? Prediction is folly, belligerent assertion pathetic. But all such arguments are past us now. If we ever spat them out it was long ago, in another age, when we both were younger than we thought we were.

This tale shall be like Tiam herself, a creature of many heads. It is in my nature to wear masks, and to speak in a multitude of voices through lips not my own. Even when I had sight, to see through a single pair of eyes was a kind of torture, for I knew – I could feel in my soul – that we with our single visions miss most of the world. We cannot help it. It is our barrier to understanding. Perhaps it is only the poets who truly resent this way of being. No matter; what I do not recall I shall invent.

There are no singular tales. A life in solitude is a life rushing to death. But a blind man will never rush; he but feels his way, as befits an uncertain world. See me, then, as a metaphor made real.

I am the poet Gallan, and my words will live for ever. This is not a boast. It is a curse. My legacy is a carcass in waiting, and it will be picked over until dust devours all there is. And when my last breath is long gone, see how the flesh still moves, see how it flinches.

When I began, I did not imagine finding my final moments here upon an altar, beneath a hovering knife. I did not believe my life was a sacrifice; not to any greater cause, nor as payment into the hands of fame and respect. I did not think any sacrifice was necessary at all.

No one lets dead poets lie in peace. We are like old meat on a crowded dinner table. Now comes the next course to jostle what’s left of us, and even the gods despair of ever cleaning up the mess. But there are truths between poets, and we both know well their worth. It is the gristle we chew without end.

Anomandaris. That is a brave title. But consider this: I was not always blind. It is not Anomander’s tale alone. My story will not fit into a small box. Indeed, he is perhaps the least of it. A man pushed from behind by many hands will go in but one direction, no matter what he wills.

It may be that I do not credit him enough. I have my reasons.

You ask: where is my place in this? It is nowhere. Come to Kharkanas, here in my memory, in my creation. Walk the Hall of Portraits and you will not find my face. Is this what it is to be lost, in the very world that made you, that holds your flesh? Do you in your world share my plight? Do you wander and wonder? Do you start at your own shadow, or awaken to rattling disbelief that this is all you are, prospects bleak, bereft of the proof of your ambition?

Or do you march past sure of your frown and indeed that is a fine box you carry . . .

Am I the world’s only lost soul?

Do not begrudge my smile at that. I too cannot be made to fit into that small box, though many will try. No, best discard me entire, if peace of mind is desired.

The table is crowded, the feast unending. Join me upon it, amidst the wretched scatter and heaps. The audience is hungry and its hunger is endless. And for that, we are thankful. And if I spoke of sacrifices, I lied.

Remember well this tale I tell, Fisher kel Tath. Should you err, the list-makers will eat you alive.

ONE

There will be peace.

The words were carved deep across the lintel stone’s facing in the ancient language of the Azathanai. The cuts looked raw, untouched by wind or rain, and because of this, they might have seemed as youthful and as innocent as the sentiment itself. A witness lacking literacy would see only the violence of the mason’s hand, but surely it is fair to say that the ignorant are not capable of irony. Yet like the house-hound who by scent alone will know a guest’s true nature, the uncomprehending witness surrenders nothing when it comes to subtle truths. Accordingly, the savage wounding of the lintel stone’s basalt face remained imposing and significant to the unversed, even as the freshness of the carved words gave pause to those who understood them.

There will be peace. Conviction is a fist of stone at the heart of all things. Its form is shaped by sure hands, the detritus quickly swept from view. It is built to withstand, built to defy challenge, and when cornered it fights without honour. There is nothing more terrible than conviction.

It was generally held that no one of Azathanai blood could be found within Dracons Hold. Indeed, few of those weary-eyed creatures from beyond Bareth Solitude ever visited the city-state of Kurald Galain, except as stone-cutters and builders of edifices, summoned to some task or venture. But the Hold’s lord was not a man to welcome questions in matters of personal inclination. If by an Azathanai hand ambivalent words were carved above the threshold to the Hold’s Great House – as if to announce a new age with either a promise or a threat – that was solely the business of Lord Draconus, Consort to Mother Dark.

In any case, it was not often of late that the Hold was home to its lord, now that he stood at her side in the Citadel of Kharkanas, making his sudden return after a night’s hard ride both disquieting and the source of whispered rumours.

The thunder of horse hoofs approached through the faint light of the sun’s rise – a light ever muted by the Hold’s nearness to the heart of Mother Dark’s power – and that sound grew until it rumbled through the arched gateway and pounded into the courtyard, scattering red clay from the road beyond. Neck arched by the reins held tight in his master’s gloved hands, the warhorse Calaras drew up, breath billowing, lather streaming down its sleek black neck and chest. The sight gave the onrushing grooms pause.

The huge man commanding this formidable beast then dismounted, abandoning the reins to dangle, and strode without comment into the Great House. Household servants scrambled like hens from his path.

There was no hint of emotion upon the Lord’s face, but this was a detail well known and not unexpected. Draconus gave nothing away, and perhaps it was the mystery in those so-dark eyes that had ever been the source of his power. His likeness, brushed by the brilliant artist Kadaspala of House Enes, now commanded pride of place in the Citadel’s Hall of Portraits, and it was indeed a hand of genius that had managed to capture the unknowable in Draconus’s visage, the hint of something beyond the perfection of his Tiste features, a deepening behind the proof of his pure blood. It was the image of a man who was king in all but name.

***

Arathan stood at the window of the Old Tower, having taken position there upon hearing the bell announcing his father’s imminent return. He watched Draconus ride into the courtyard, eyes missing nothing, one hand up to his face as he bit skin and pieces of nail from his fingers – the tips were red nubs, swollen with endless spit, and on occasion they bled, staining the sheets of his bed at night. He studied the movements of Draconus as the huge man dismounted, carelessly abandoning Calaras to the grooms, to then stride towards the entrance.

The three-storey tower commanded the northwest corner of the Great House, with the house’s main doors to the right and out of sight from the upper floor’s window. At moments like these, Arathan would tense, breath held, straining with all his senses for the moment when his father crossed the threshold and set foot on the hard bared stones of the vestibule. He waited, for a change in the atmosphere, a trembling in the ancient walls of the edifice, the very thunder of the Lord’s presence.

As ever, there was nothing. And Arathan never knew if the failing was his, or if his father’s power was sealed away inside that imposing frame and behind those unerring eyes, contained by a will verging on perfection. He suspected the former – he saw how others reacted, the tightening of expressions among the highborn, the shying away of those of lesser rank, and how on occasion both reactions warred within the same individual. Draconus was feared for reasons Arathan could not comprehend.

In truth, he did not expect more of himself in this matter. He was a bastard son, after all, and a child born of a mother he never knew and had never heard named. In his seventeen years of life he had been in the same room with his father perhaps twenty times; surely no more than that, and not once had Draconus addressed him. He was not privileged to dine in the main hall; he was tutored in private and taught the use of weapons alongside the recruits of the Houseblades. Even in the days and nights immediately following his near-drowning, when in his ninth winter he’d fallen through ice, he’d been attended to by the guards’ healer, and had received no visitors barring his three younger half-sisters, who had peered in through the doorway – a trio of round, wide-eyed faces – only to immediately flee down the corridor voicing squeals.

For years, their reaction upon seeing him had led Arathan to believe he was unaccountably ugly, a conviction that had first brought his hands to his face in a habit of hiding his features, and soon the kiss of his own fingertips served for all the tactile reassurance he required. He no longer believed himself to be ugly. Simply . . . plain, not worthy of notice by anyone.

Though no one ever spoke of his mother, Arathan knew that she had named him. His father’s predilections on such matters were far crueller. He told himself that he remembered his half-sisters’ mother, a brooding, heavy woman with a strange face, who had either died or departed shortly after weaning the triplets she had borne, but a later comment from Tutor Sagander suggested that the woman he’d remembered had been a wet-nurse, a witch of the Dog-Runners who dwelt beyond the Solitude. Still, he preferred to think of her as the girls’ mother, too kind-hearted to give them the names they now possessed – names that, to Arathan’s mind, shackled each sister like a curse.

Envy. Spite. Malice. They remained infrequent visitors to his company. Flighty as birds glimpsed from the corner of an eye. Whispering from around corners in the corridors and behind doors he walked past. Clearly, they found him a source of great amusement.

Now in the first years of adulthood, Arathan saw himself as a prisoner, or perhaps a hostage in the traditional manner of alliance-binding among the Greater Houses and Holds. He was not of the Dracons family; though there had been no efforts at hiding his bloodline, in fact the very indifference of this detail only emphasized its irrelevance. Seeds spill where they may, but a sire must look into the eyes to make the child his own. And this Draconus would not do. Besides, there was little of Tiste blood in him – he had not the fair skin or tall frame, and his eyes, while dark, lacked the mercurial ambivalence of the pureborn. In these details, he was the same as his sisters. Where, then, the blood of their father?

It hides. Somehow, it hides deep within us.

Draconus would not acknowledge him, but that was no cause for resentment in Arathan’s mind. Man or woman, once childhood was past the world beyond must be met, and a place in it made, by a will entirely dependent upon its own resources. And the shaping of that world, its weight and weft, was a match to the strength of that will. In this way, Kurald Galain society was a true map of talent and capacity. Or so Sagander told him, almost daily.

Whether in the court of the Citadel or among the March villages, there could be no dissembling. The insipid and the incompetent had no place in which to hide their failings. ‘This is natural justice, Arathan, and thus by every measure it is superior to the justice of, say, the Forulkan, or the Jaghut.’ Arathan had no good reason to believe otherwise. This world, so forcefully espoused by his tutor, was all he had ever known.

And yet he . . . doubted.

Sandalled feet slapped closer up the spiral stairs behind him, and Arathan turned in some surprise. He had long since claimed this tower for his own, made himself lord of its dusty webs, its shadows and echoes. Only here could he be himself, with no one batting his hand away from his mouth, or mocking his ruined fingertips. No one visited him here; the house-bells called him when lessons or meals were imminent; he measured his days and nights by those muted chimes.

The footsteps approached. His heart thumped in his chest. He snatched his hand away from his mouth, wiped the fingers on his tunic, and stood facing the gap of the stairs.

The figure that climbed into view startled him. One of his halfsisters, the shortest of the three – last from the womb – her face flushed with the effort of the climb, her breath coming in little gasps. Dark eyes found his. ‘Arathan.’

She had never before addressed him. He did not know how to respond.

‘It’s me,’ she said, eyes flaring as if in anger. ‘Malice. Your sister, Malice.’

‘Names shouldn’t be curses,’ Arathan said without thinking.

If his words shocked her, the only indication was a faint tilt of her head as she regarded him. ‘So you’re not the simpleton Envy says you are. Good. Father will be . . . relieved.’

‘Father?’

‘You are summoned, Arathan. Right now – I’m to bring you to him.’

‘Father?’

She scowled. ‘She knew you’d be hiding here, like a redge in a hole. Said you were just as thick. Are you? Is she right? Are you a redge? She’s always right – or so she’ll tell you.’ She darted close and took Arathan’s left wrist, tugged him along as she returned to the stairs.

He did not resist.

Father had summoned him. He could think of only one reason for that.

I am about to be cast out.

The dusty air of the Old Tower stairs swirled round them as they descended, and the peace of this place felt shattered. But soon it would settle again, and the emptiness would return, like an ousted king to his throne, and Arathan knew that he would never again challenge that domain. It had been a foolish conceit, a childish game.

‘In natural justice, Arathan, the weak cannot hide, unless we grant them the privilege. And understand, it is ever a privilege, for which the weak should be eternally grateful. At any given moment, should the strong will it, they can swing a sword and end the life of the weak. And that will be today’s lesson. Forbearance.’

A redge in a hole – the beast’s life is tolerated, until its presence becomes a nuisance, and then the dogs are loosed down the earthen tunnel, into the warrens, and somewhere beneath the ground the redge is torn apart, ripped to pieces. Or driven into the open, where wait spears and swords eager to take its life.

Either way, the creature was clearly unmindful of the privileges granted to it.

All the lessons Sagander delivered to Arathan circled like wolves around weakness, and the proper place of those cursed with it. No, Arathan was not a simpleton. He understood well enough.

And, one day, he would hurt Draconus, in ways not yet imaginable. Father, I believe I am your weakness.

In the meantime, as he hurried along behind Malice, her grip tight on his wrist, he brought up his other hand, and chewed.

Forge of Darkness (2012)

Bantam Press (UK)

Tor Books (US)

Steven Erikson returns to the Malazan world with the first book in a dark and revelatory new epic fantasy trilogy that tells the tragic story of the downfall of an ancient realm…

Now is the time to tell a tragic tale that sets the stage for all the tales yet to come . . . and all those already told.

It is the Age of Darkness and the realm called Kuruld Galain—home of the Tiste Andii and ruled over by Mother Dark from her citadel in Kharkanas—is in a perilous state. For the commoners’ great warrior hero, Vatha Urusander, is being championed by his followers to take Mother Dark’s hand in marriage but her Consort, Lord Draconus, stands in the way of such arrogant ambition.

As the impending clash between these two rival powers sends fissures rippling across the land and rumours of civil war flare and take hold amongst the people, so an ancient power emerges from seas once thought to be long dead. None can fathom its true purpose nor comprehend its potential. And caught in the middle of this seemingly inevitable conflagration are the First Sons of Darkness—Anomander, Andarist and Silchas Ruin of the Purake Hold—and they are about reshape the world…

Here begins Steven Erikson’s epic tale of bitter family rivalries, of jealousies and betrayals, of wild magic and unfettered power…and of the forging of a sword.

Bantam/Transworld (UK) • London (2012) • hard cover • ISBN: 978-0593062173

Tor Books • New York (2012) • hard cover • ISBN: 978-0765323569

July 9, 2012

The Wurms of Blearmouth (2012)

Steven Erikson’s new Bauchelain and Korbal Broach novella, The Wurms of Blearmouth, follows on from where The Lees of Laughter’s End (2007) left off.

Tyranny comes in many guises, and tyrants will thrive in palaces and one room hovels, in back alleys and playgrounds. Tyrants abound on the verges of civilization, where disorder frays the rule of civil conduct, and all propriety surrenders to brutal imposition. Millions are made to kneel and yet more millions die horrible deaths in a welter of suffering and misery.

But we’ll leave all that behind as we plunge into escapist fantasy of the most irrelevant kind, and in the ragged wake of the tale told in Lees of Laughter’s End, our most civil adventurers, Bauchelain and Korbal Broach, along with their suitably phlegmatic manservant, Emancipor Reese, make gentle landing upon a peaceful beach, beneath a quaint village above the strand and lying at the foot of a majestic castle, and therein make acquaintance with the soft-hearted and generous folk of Spendrugle, which lies at the mouth of the Blear River and falls under the benign rule of the Lord of Wurms in his lovely keep.

Make welcome, then, to Spendrugle’s memorable residents, including the man who should have stayed dead, the woman whose prayers should never have been answered, the tax collector everyone ignores, the ex-husband town militiaman who never married, the beachcomber who lives in his own beard, and the now singular lizard cat who used to be plural, and the girl who likes to pee in your lap. And of course, hovering over all, the denizen of the castle keep, Lord –

Ah, but there lies this tale, and so endeth this blurb, with one last observation: when tyrants collide, they have dinner.

And a good time is had by all.

PS Publishing (UK)

PS Publishing (UK)

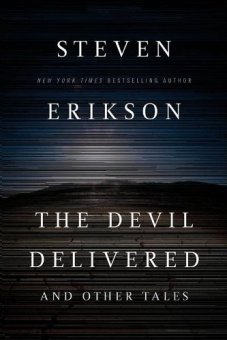

The Devil Delivered and Other Tales (2012)

Tor Books (US)

Steven Erikson has carved a name for himself among the pantheon of great fantasy writers. But his

masterful storytelling and prose style go beyond the awe-inspiring Malazan world.

This three novella collection is comprised of the three separately published PS Publishing titles:

The Devil Delivered (2005)

Fishin’ With Grandma Matchie (2005)

Revolvo (2008)

In The Devil Delivered and Other Tales,

Erikson tells three different, but captivating stories:

“The Devil Delivered” tells a story set within the near future, where the land owned by the great Lakota Nation blisters beneath an ozone hole the size of the Great Plains. As the natural world falls victim to its wrath, and scientists scramble to understand it, a lone anthropologist wanders the deadlands, recording observations that threaten to bring the entire world to its knees.

“Revolvo” takes place in an alternate Earth where evolution took an interesting turn and the arts scene is ruled by technocrats who thrive in a secret, nepotistic society of granting agencies, bursaries, and peer-review boards, all designed to permit self-proclaimed artists to survive without an audience.

“Fishin’ with Grandma Matchie” is told in the voice a nine-year-old boy, writing the story of his summer vacation. What starts as a typical recount of a trip to see Grandma quickly becomes a stunning fantastical journey into imagination and perception in the wild world that Grandma Matchie inhabits.

Tor Books (US) • New York (2012) • hard cover • ISBN: 978-0-7653-3002-4

Tor Books (US) • New York (2012) • trade paper • ISBN: 978-0-7653-3003-1