Nate Silver's Blog, page 149

September 8, 2015

If Donald Trump Can Win The Nomination, Ben Carson Could Too

Labor Day, when campaigns traditionally begin to rev up, is in the rearview mirror, and the Republican primary field is still crowded and messy. But Ben Carson, a neurosurgeon, has been climbing in the polls. FiveThirtyEight’s politics team gathered in Slack to talk about the Carson “surge.” This is an edited transcript of the conversation.

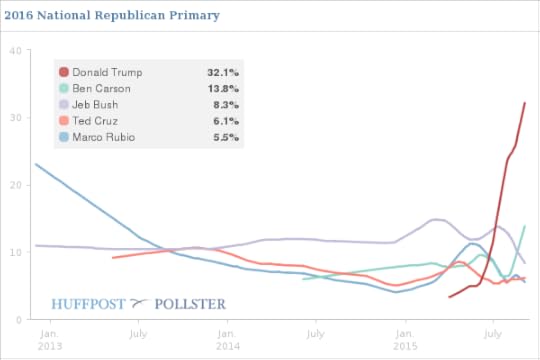

micah (Micah Cohen, senior editor): Nate and Harry, Ben Carson is on the upswing in national polls. Check out the light teal line here:

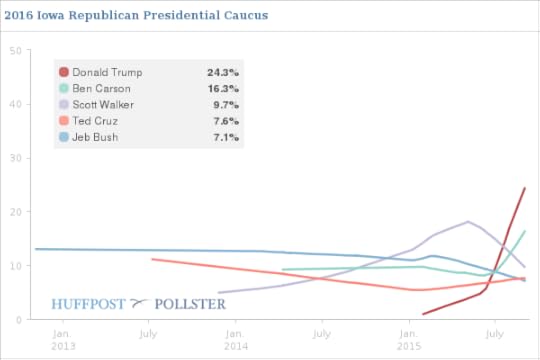

He’s also made gains in Iowa:

And he’s done so largely without the media’s help. Will the Carson surge just be a blip à la Michele Bachmann and Herman Cain in the 2012 cycle? Or can Carson take down The Donald?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): I, for one, look forward to the Carson-Trump unity ticket and a close general election against Biden-Warren.

hjenten-heynawl (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Well, let’s start off with a look at the latest polling. We see Carson climbing, but we see him doing much better in Iowa than in New Hampshire. This weekend, for instance, a new Marist poll had Carson in second place in Iowa, with 22 percent, and in third place in New Hampshire, with 11 percent. And take a look at which groups Carson is doing best with in Iowa: It’s white evangelicals. That’s unlike Trump, who tends not to outperform with any one group in particular.

natesilver: Indeed, it doesn’t seem like Carson’s and Trump’s supporters have all that much in common. Which is good news for Trump, in a way? Still, part of the question is what would happen if Carson started to command some of the media attention that Trump was monopolizing previously.

micah: I feel like Carson is starting to get some attention.

hjenten-heynawl: Trumpnado may be degraded from different angles. You knock him in Iowa with Carson, then you hit him in New Hampshire with John Kasich (or Jeb Bush).

But on the media coverage, you could easily see Trump come back to the pack merely as a result of Carson gaining attention in Iowa, which could open the door to non-Trump candidates elsewhere.

natesilver: Well, there’s a discussion about whether Iowa is a “must-win” for Trump. To the extent that his support in polls partly reflects a bandwagon effect — people think he’s a winner because he’s leading in the polls and that all the other GOP candidates are losers — finishing second or third in Iowa could hurt him.

But we’re probably also getting way, way ahead of ourselves. If Trump’s relying on a bandwagon effect, then what happens if Carson passes him in some national polls, for instance?

hjenten-heynawl: Let me point out one other big difference between Carson and Trump. Carson’s favorable rating in the latest Monmouth University poll was 67 percent. His unfavorable rating was just 6 percent. Trump, even with improving favorables, was at a 59-29 split.

micah: So aside from stealing some of the spotlight from Trump, can Carson eat into his actual support? They’re certainly different stylistically (Trump is loud, Carson is quiet), and as you said, Trump draws about equally from across the GOP, while Carson pulls support from the evangelical right. But neither has held office before; they’re both outsiders. Can Carson steal some actual Trump backers?

natesilver: Can I make an observation? It’s interesting that we’re succumbing to the temptation of filtering all questions about the GOP primary through the lens of Trump.

micah:

natesilver: I think Carson and Trump are actually pretty different. Not just in their presentation. Their policy positions are pretty different. Carson has more or less conventional conservative / tea party positions. Trump, uh, doesn’t.

hjenten-heynawl: Right. I would say that Trump really isn’t much of anything. He’s more an attitude than an ideology. Carson, on the other hand, has specific groups with whom he does best. This, I think, is a key difference. To me, Carson is much more like something we’ve seen before. Trump, on the other hand, is more of an original.

natesilver: I’d also argue, though, that Carson is a little bit different from the “flavor-of-the-month” candidates from 2011. At least in terms of his demeanor, he’s much less bombastic than someone like Gingrich or Bachmann. And he has a much more compelling life story — it’s not an exaggeration to say it’s a heroic life story.

micah: Carson may not yell, but he has said some pretty Trumpian things.

hjenten-heynawl: This is why I think Carson is dangerous to someone like Trump. Even when he says something that certain people might call politically incorrect, he says it with a smile.

And this makes him far more likable, while still “telling it like it is.”

natesilver: I don’t know @micah. He’s said a few Trumpian things. But Bush and Scott Walker have had a few of their own gaffes too, for example.

If you watch Carson’s announcement speech, he’s pretty mild-mannered and low-key throughout:

At the very least, he’s a little hard to characterize. Which is part of the reason he hasn’t gotten that much press coverage, methinks. He doesn’t fit that neatly into any of the media’s templates for a candidate.

micah: So that suggests he could have more staying power than a Bachmann or Cain?

hjenten-heynawl: I’ve learned that it’s difficult to predict how long a surge will last. But what we can say is that Carson isn’t going up against a mainstream Republican. He’s going up against Trump. Carson is also much better-liked across the party than either of the two you noted. So the recipe is there for a little more staying power.

natesilver: So, Harry. Who is more likely to be the Republican nominee, Ben Carson or Donald Trump?

micah: Good question! No hedging, Harry

hjenten-heynawl: Ben Carson, and I’m not sure there is much doubt in my mind. Reasons include:

He’s better-liked by Republican voters, at least at this point.He’s better-liked by party actors. He has a much more presidential demeanor than Trump. He also happens to be African-American at a time the GOP wants to reach out to black voters.This isn’t to say he is anything more than a long shot, but he’s a trip to the West Coast while Trump is a trip to the moon.

micah: And, Nate, how would you answer your own question?

natesilver: Hold on — I’ve gotta take a phone call here …

micah: We’ll wait …

natesilver: [crickets]

micah: Coward.

natesilver: I guess I’d put each of their chances at about 5 percent.

micah: Interesting. You don’t buy Harry’s argument? Or his West Coast/moon metaphor?

natesilver: Obviously, Carson has much higher favorables. He also has policy positions that are much more in line with the GOP mainstream. So, you can imagine a universe in which GOP elites grudgingly tolerate Carson, even if he’s not their first (or second or third or sixth) choice, whereas they’ll do everything in their power to make sure that Trump is not the nominee.

On the other hand, Trump has survived quite a bit more scrutiny so far. Not very much scrutiny as compared to what he’ll face between now and February. But some of it, certainly, and much more than Carson.

Furthermore, it’s not clear to me how interested Carson is in actually becoming president. Or how much relevant experience he has in running a campaign. Trump’s experience as a celebrity and mogul and television star is more transferable to the political stage than Carson’s as a neurosurgeon.

Put another way, when Carson says he’s not a politician … that might be somewhat literally true. Whereas it’s a rhetorical line for Trump.

hjenten-heynawl: I would give Trump a better chance of getting say 10 or 15 percent in the primary vote, but I’d give Carson a better chance of winning the nomination. Even if everything goes right for The Donald, a wall likely awaits him (and not the wall he wants). Carson, on the other hand, may flame out. But if he can keep his stuff together, then you could potentially see him coming close to the nomination. Again, neither has all that great of a shot.

natesilver: We’ve talked before about whether Trump fits into the template of a bandwagon candidate (like Newt Gingrich or Cain) or a factional candidate (like Pat Buchanan). The answer could be: both?

So sooner or later — maybe later! — his numbers fall to Earth a bit. But he’s still left with 15 percent support, or something.

Trump has led the polls for two months or so. But he’s led them in July and August, at which point there’s not very much real political news. And there was only one debate, as compared with the more active schedules in past years.

So in political time, those two months aren’t really very long. This is probably a slight exaggeration, but it might be easier to lead the polls for two months in July and August than for two weeks in December, for instance. We still have a lot to learn about how GOP voters will behave as the campaign evolves.

micah: If the Trumpnado is deprived of oxygen, where do his voters go?

hjenten-heynawl: I think Trump supporters could go any and everywhere. They tend to be more anti-Washington than voters on average, but they aren’t any more liberal or conservative. That’s why Bush and Walker and Rand Paul (among others) have all fallen even though there isn’t an ideological tie between them. I think Carson can eat away at Trump’s Christian Conservative voters, but overall, there isn’t a natural home for Trumpers.

micah: Last question — we’ve talked before about whether the GOP establishment was losing control of the nominating process and decided they weren’t. Have Carson’s gains (or Carly Fiorina’s) made either of you rethink that? The more establishment candidates — Jeb Bush, Scott Walker, Marco Rubio, John Kasich (outside of New Hampshire) — still have yet to gain much traction. Is something different this time? (BROKERED CONVENTION!!!!!!!)

hjenten-heynawl: Talk to me when we aren’t five months out from Iowa, or if there is one candidate who receives the lion’s share of endorsements and doesn’t win any states. Or put another way, I’ll start rethinking that when a candidate who isn’t well-liked by the party actors wins a bunch of states.

natesilver: OK, but a couple of things are different this time around. First, there are 17 candidates running.

hjenten-heynawl: Jim Gilmore is not a real candidate. Just FYI.

natesilver: Fine, 16 candidates. Secondly, as you pointed out the other day, Harry, the GOP establishment has never been quite so slow to settle on a candidate, at least judging by the number of endorsements.

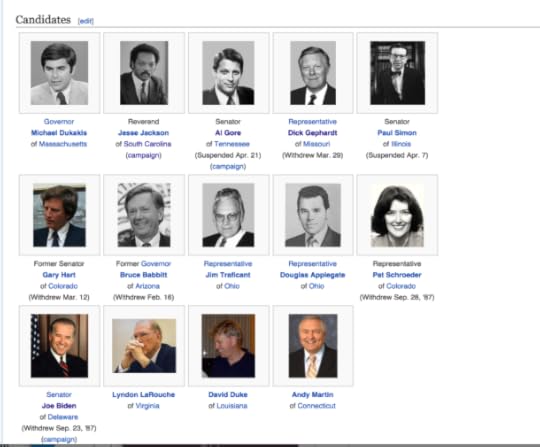

hjenten-heynawl: Things may be different for Republicans, but we have examples of this on the Democratic side. You can look at 1988 or 2004 on the Democratic side, but from each field, you got what most would call a traditional candidate.

natesilver: Examples where there were 17 candidates running? (Err, 16?) Maybe 1972 on the Democratic side. But that resulted in George McGovern, who certainly wasn’t an establishment favorite, winning the nomination.

hjenten-heynawl: I’m talking about very large fields. Look at 1988 on the Democratic side (from Wikipedia):

natesilver: Harry, you’re including some very dubious “candidates” on that 1988 list.

hjenten-heynawl: Take it up with Wikipedia. I mean, there are some “dubious” candidates on the GOP side, like George Pataki. Either way, yes, 17 or 16 is a lot, but we’ve had 10+ candidate fields before — fields that winnowed and worked their way out. I’m more than open to saying this time could be different, but we should also say that it’s still early and we should let the priors lead the way.

natesilver: Sure, I agree that the most likely outcome is some establishment-ish candidate — Bush, Rubio, Kasich, Walker — gaining momentum at the right time and winning the nomination. It’s still very early — too early to be paying much attention to polls. And if you do want to look at polls, Rubio and Walker have very high favorability ratings, which speaks against the notion that GOP voters are rejecting establishment choices wholesale.

But I also don’t think we should be all “LOL, brokered convention.” It’s not that far-fetched this year, as compared to most years in the past.

hjenten-heynawl: What’s far-fetched?

natesilver: In our chat a few weeks ago, I put the chance of a nomination that was genuinely uncertain in June (after the last primaries and caucuses) at 20 percent. (That’s not quite the same thing as a brokered convention, since the nomination could be resolved through backchannels before the convention convened.)

Maybe I’d put the chance at 25 percent now? Nothing all that fundamental has changed. But if there’s a universe where Trump is winning some delegates and someone like Carson or Ted Cruz is winning some also, that makes the GOP’s math a little messier.

hjenten-heynawl: Wow, that’s quite high. I’d put it closer to 10 percent. Granted that’s higher than I give the chance of Carson winning the GOP nomination.

micah: We’ll have to agree to disagree, and the readers can decide who’s right in the comments. Thanks, everyone!

September 2, 2015

Keep Calm And Ignore The 2016 ‘Game Changers’

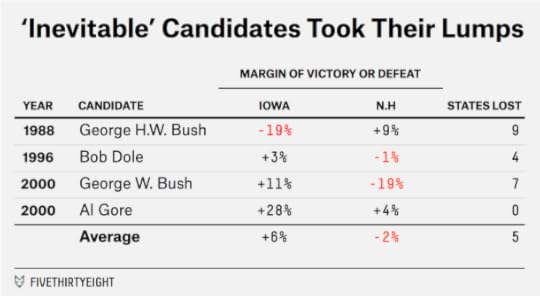

If you were to rank the most exciting presidential nomination contests, the 1996 Republican race would be near the bottom. Bob Dole, the “next-in-line” GOP candidate and the Senate majority leader, built up a huge lead in polls and endorsements early in the race and was never seriously challenged for the nomination. Dole did lose the New Hampshire primary by a single point to Pat Buchanan. But the field soon consolidated around him, and he went on to win 44 of 50 states.

And yet, contemporaneous accounts of the sleepy-seeming 1996 campaign portrayed it as incredibly dramatic, full of “unexpected” twists and “unpredictable” turns. Take this March 7, 1996, article from The New York Times, for example — it was written after Dole had won 12 consecutive primaries and caucuses in the previous week. There are four expressions of surprise in a single paragraph: It’s taken as shocking that the early primaries were as competitive as they were, but equally “striking” that Dole rebounded so quickly from them.

After an unpredictable early stretch of primaries, where candidates seemed to flicker out like trick birthday candles, only to re-ignite unexpectedly, Mr. Dole’s return to a commanding lead so early in the voting was striking. The positioning and sorting of the field yesterday was particularly unusual: Almost simultaneously, Mr. Lugar and Mr. Alexander bowed out, as Governor Bush and Mr. Kemp put forth their dueling endorsements.

I don’t mean to pick on this article, which happens to have been written by a terrific journalist,1 but it’s typical of the breathless fashion in which developments on the campaign trail are reported. There is a constant series of overcorrections in the conventional wisdom. In this case, because the initial threat to Dole was overstated by the press — Buchanan, a factional candidate, had little chance to see his support grow beyond the 27 percent of the vote he won in New Hampshire2 — Dole’s “comeback” was incorrectly portrayed as unexpected and dramatic.

These biases hold in coverage of the general election too, of course: There were 68 purported “game changers” in the 2012 general election, most of which turned out to be irrelevant. But for the political observer trying to sift faux game changers from genuine twists in the campaign, the primaries present a couple of additional complications.

First, there are far more opportunities to be “surprised” in the primaries. Let’s start with the most basic stuff. In a nomination race, there might be a dozen or more candidates, instead of just two. And states vote one at a time, instead of all at once.

Furthermore, in a nomination race, there is an abundance of metrics by which you might judge the campaigns: national polls, Iowa polls, New Hampshire polls, favorability ratings, endorsements, fundraising, staffing, even crowd sizes and yard signs. Eventually, we’ll also be able to look at delegates, which can be counted in many different ways. For any of these metrics, you can report on the level of support (“Hillary Clinton is polling at 48 percent”), the trend (“she’s lost 4 percentage points since last month”), or even the second derivative (“she’s losing ground, but not as quickly as before”). Multiply 23 candidates3 by 10 metrics by three ways of reporting on those metrics, and you have 690 opportunities to be “surprised” at any given time.

In a sense, the primaries are a lot like the NCAA basketball tournament: You know there are going to be some surprises. The odds of every favorite winning every game in the NCAA tournament are longer than a billion-to-one against. And yet, in the end, one of the front-runners usually wins. (Since the men’s tournament expanded to 64 teams in 1985, all but three champions have been No. 4 seeds or better.)

So be wary of grand pronouncements about What It All Means based on a handful of “surprising” developments. Is Scott Walker’s campaign off to an “unexpectedly” bad start, for instance? Maybe. (I wouldn’t be thrilled if I were one of Walker’s strategists. I’d also remind myself that we have five months to go before the Iowa caucuses.) Even if you grant that Walker is having some problems, however, it would be stunning if all the Democratic and Republican campaigns were doing exactly as well as pundits anticipated. At any given moment, some campaigns are bound to be struggling to meet expectations, or exceeding them.

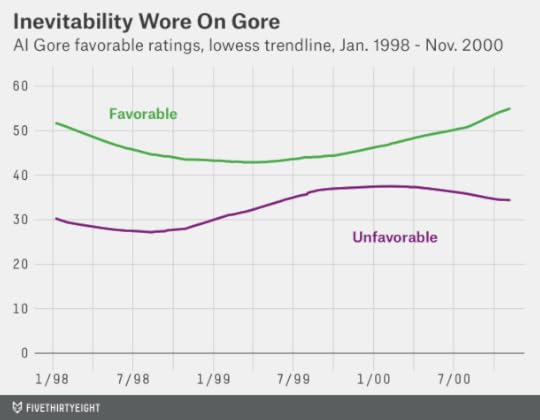

Similarly, while one might not have predicted that Bernie Sanders would be the one to do it, it was reasonably likely that some rival would emerge to Hillary Clinton. It’s happened for every non-incumbent front-runner in the past: Buchanan for Dole; Bill Bradley for Al Gore.

The other big difference between the general election and primaries is that polls are not very reliable in the primaries. They improve as you get closer to the election, although only up to a point. But they have little meaning now, five months before the first states vote.

It’s not only that the polls have a poor predictive track record — at this point in the past four competitive races, the leaders in national polls were Joe Lieberman, Rudy Giuliani, Hillary Clinton and Rick Perry, none of whom won the nomination — but also that they don’t have a lot of intrinsic meaning. At this point, the polls you see reported on are surveying broad groups of Republican- or Democratic-leaning adults who are relatively unlikely to actually vote in the primaries and caucuses and who haven’t been paying all that much attention to the campaigns. The ones who eventually do vote will have been subjected to hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of advertising, had their door knocked on several times, and seen a half-dozen more debates. The ballots they see may not resemble the one the pollsters are testing since it’s likely that (at least on the GOP side) several of the candidates will have dropped out by the time their state votes.

Some reporters object to this by saying that the polls are meaningful to the extent that they influence the behavior of the campaigns: If Joe Biden enters the race because he reads the polls as indicating that Clinton is vulnerable, that could matter, for instance.

Fair enough. But it’s dubious to compare hypothesized behavior with actual outcomes we’ve seen in past election years. If Biden or Mitt Romney thinks the field is weak and makes a late entry, that will be interesting. If Donald Trump or Sanders actually wins the nomination or comes very close to doing so, that will be a watershed in American political history. But there’s a high rate of false alarms compared with the number of late-entry candidates that actually make a bid or watershed moments that actually occur.

None of this is to imply that nominations are all that easy to forecast. And some things this year have been genuinely surprising. In particular, that there are 17 Republican candidates, including a dozen or so who have traditional credentials for the White House, is unprecedented. If you want to develop a theory about how “this time is different,” figuring out how to explain the size of the Republican field (and how it might affect the race) seems like a good starting point.

Oddly, this abundance of candidates has been somewhat taken for granted in campaign coverage, even though it potentially plays a big role in explaining Trump’s position in the polls, among other things. The reason may be that it’s something we’ve known about for a long time; there aren’t a lot of clicks to be had from the headline “17 Candidates Still Running; Nothing Else Much Changed Today.” Chasing down the bright, shiny object is more exciting, but usually not more revealing.

August 31, 2015

A Ben Carson Surge May Test Trump

One question we’ve asked about Donald Trump’s campaign is what would happen if another candidate were to get a surge of media coverage, throwing a wrench in the works of Trump’s perpetual attention machine. Based on the latest polls, we may soon get the best test of this question since Trump entered the race.

The potential surger is Ben Carson, the much-awarded neurosurgeon who is running for political office for the first time. Carson is near the top of the Republican field in two new polls of Iowa. A Monmouth University poll has Carson with 23 percent of the vote and tied for the lead with Trump, while the Des Moines Register’s poll has Carson in second place, with 18 percent of the vote to Trump’s 23 percent. Carson has also been gaining ground in national polls and is in second place behind Trump, according to Huffington Post Pollster’s averaging method.

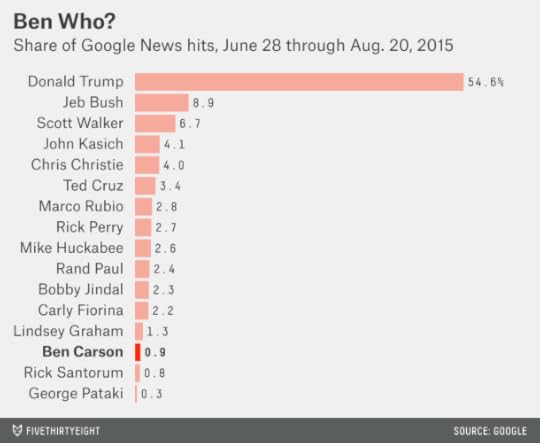

Carson’s gains in the polls have come organically — in fact, he’s been receiving remarkably little media attention. From June 28 through Aug. 20, Carson received only 0.9 percent of the news coverage of the top 161 Republican candidates, based on the number of Google News “hits” he received. That puts him at 14th in the field. Trump has received about 60 times more media coverage than Carson.

While it can be foolish to predict what happens to the polls in the short run, there’s a pretty obvious case to be made that Carson is on an upswing as part of a “discovery, scrutiny and decline” polling cycle of the sort that Newt Gingrich and Herman Cain (among others) experienced in 2011. If Carson’s doing this well with so little media attention, imagine what happens when he gets some. Polls will trigger more coverage of Carson’s campaign, which will in turn improve his standing in the polls, which will produce yet more coverage, and so forth.

Carson also has outstanding favorability ratings among Republicans, which could give him more room to grow. And it’s not as though he’s a dull story to cover. While Carson is more mild-mannered than Trump — and possibly a lot smarter — he, like Trump, has a history of stoking controversy through impolitic statements.

The question is what happens to Trump’s numbers when Carson surges. (Or if Carson doesn’t, when another candidate like Ted Cruz inevitably does some weeks or months from now.) If Trump is more like the Gingriches and Cains of the world, his support may erode pretty quickly once there’s another GOP “flavor of the month” who appeals to voters seeking an outsider to mainstream politics. An alternative possibility, however, is that Trump is more like a Pat Buchanan or Ron Paul — a factional candidate who is relatively immune from shifts of opinion elsewhere in the Republican field, but also has a low ceiling on his support. Either way, Trump is not very likely to win the Republican nomination — and neither is Carson — but we’ll learn something about the nature of his support.

August 28, 2015

Most Of The Biden Speculation Is Malarkey

Another day, another batch of mostly redundant and anonymously sourced stories about whether Vice President Joe Biden will run for president. Some of those stories, however, are getting ridiculous. So FiveThirtyEight’s politics writers met in Slack to pick over the latest Biden coverage, our own assumptions and the state of the 2016 Democratic primary. This is an edited transcript of the conversation.

micah (Micah Cohen, senior editor): So, the will he/won’t he speculation about Joe Biden hasn’t slowed down, but do either of you buy the argument that a Biden run could actually help Hillary Clinton?

hjenten-heynawl (Harry Enten, senior political writer): I don’t think it would be particularly helpful to Clinton. Forget about all the BS about whether Clinton runs better when she’s in trouble. Personally, I never got that. If she were so good at running when she was in trouble, then why did she lose in 2008?

Rather, why would Biden run? Sure, he’s in his 70s and this is his last shot, but he also has a family to take care of. He’d likely only run if he concludes he has a better than nominal chance of winning. And that conclusion would be quite different from what the current metrics, such as endorsements, suggest. Biden may have an insight on the invisible primary that isn’t visible to the rest of us.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): The irony is that the media has exaggerated all sorts of threats to Clinton, who remains in good shape for the nomination. But then you have the one thing that would be a tangibly bad sign for her campaign — the vice president of the United States running for the nomination against her! — and there are lots of “smart takes” about how it could help Clinton.

hjenten-heynawl: What we’ve argued this entire time is that Sen. Bernie Sanders has a weakness among the party actors (i.e., he doesn’t have any endorsements), and that he has no longtime connections to the Democratic Party (remember, he’s not a Democrat). Biden, on the other hand, has been in major federal office in Washington since 1973. He’s someone who could conceivably reach out to all members of the party. He’s already polling better among African-Americans than Sanders, for instance.

micah: Let’s break this down a little: Both of you seem to think Biden entering the race is inherently bad for Clinton — he’d be the most serious competition for the nomination she’s faced. But would there be a couple side benefits, like that by giving the media a horse race to cover, there would be less focus on Clinton’s scandals?

natesilver: Well, first of all, it’s not just that Biden would be a more formidable competitor to Clinton than Sanders. I don’t know that Biden would be all that great a candidate, in fact. But Biden running would signal that concern about Clinton among Democratic Party elites had gone from the bedwetting stage to something more serious.

micah: Is bedwetting not serious?

hjenten-heynawl: I mean, it depends how old you are.

natesilver: But the other big problem (as we and others have pointed out before) is that Biden doesn’t have much rationale to run other than if Clinton has “trust”/scandal problems. He might never come out and say it, but that would be the whole basis for his campaign. They don’t really differ in any meaningful way on policy.

micah: But your logic seems circular: “Biden will only enter the race if Clinton is in big trouble, and therefore if Biden enters the race it means Clinton is in trouble.” What if all the party actors are telling Biden that he shouldn’t run, that they’re backing Clinton, and Biden just wants to run? It’s his last chance. And he enters the race.

natesilver: What I’m saying is that there’s a lot of information we’re not privy to, about what Democratic elites are thinking. Sure, there’s some reporting on it, but a lot of that reporting needs to be looked at skeptically — like because it relies on anonymous sourcing, or cherry-picked information from a media that would like to make the race seem competitive. The one tangible sign we have about what Democratic elites are thinking — endorsements — looks really good for Clinton. But Biden running would be a tangible sign too.

Contra Maureen Dowd or whatever, this isn’t necessarily a personal decision for Biden, or at least not entirely one. He’s a party guy. He’s the vice president. He’s not likely to run unless he thinks it’s in Democrats’ best interest.

hjenten-heynawl: Endorsements are merely a proxy for intra-party support. And proxies are wrong from time to time. They’re imperfect. And I don’t buy Biden is desperate to run. He reportedly indicated this week in a phone call with Democratic National Committee members that he and his family are grieving. The man lost his best friend and son. He wants to be there for his family. If I lost my father (my best friend), I don’t take off running for president just because I feel like it. I run because I think I can help my party, and because I think I can win.

natesilver: Right. It’s possible that Biden assesses the problem and miscalculates. But running for president would be a calculated decision on his behalf.

And, by the way, if you read the reporting on Biden carefully, it suggests that the decision is very, very calculated. He’s taking as long as possible to decide whether to enter — and at a time when it’s already pretty darn late to begin a campaign — because he wants to collect more information on whether Clinton’s in trouble or not.

hjenten-heynawl: BINGO. He’s meeting with a ton of people who represent different wings of the party, such as Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Richard Trumka (head of the AFL-CIO). He’s doing that, one would think, because he wants to understand what they are seeing. What are their people, their constituents, telling them.

micah: OK, so let’s say Biden gets in. The night before he announces, he’s sitting with his family and some advisers and they’re talking about why they can beat Clinton (based on everything they hear during these weeks of meetings). What are they saying? Does it all come down to email/scandal? Or would they be pointing to something else in the Clinton campaign or electorate? (I want data.)

natesilver: If you want data, and Biden’s camp is looking at the same data, then they shouldn’t be running in the first place. Unless they think the scandal will be Clinton’s undoing.

Clinton remains extremely popular with Democrats, and that popularity is pretty broad-based. White liberals might not like her as much as white moderates, Hispanics, or African-Americans, but as we’ve argued before, their support for Sanders is more an indication that they like him than that they dislike Clinton.

Some of the reporting around what Biden’s coalition would be doesn’t make any sense. See, for example, from Politico:

Biden’s circle has identified what they see as their potential voting blocs: Reagan Democrats, Jews, an LGBT base that largely credits him with pushing President Barack Obama into supporting gay marriage, and Rust Belt voters. They believe he’ll benefit from better stump skills than any of the other candidates running.

There’s no evidence that any of these groups are weaknesses for Clinton. Nor are they all that large, nor do they have very much in common.

micah: What about the Quinnipiac poll out this week showing Biden running better than Clinton against Republicans in general election matchups? And that voters don’t think Clinton is trustworthy or honest?

natesilver: I don’t think you can compare a declared candidate in Clinton — who’s been getting a ton of scrutiny from the press, some deserved and some not — against a hypothetical candidate who has a halo around him because the press would love to see a huge fight for the nomination.

Over the long run, Clinton’s favorability numbers have been no worse than Biden’s. Often a little better.

hjenten-heynawl: General election polls of candidates who aren’t running in the primary are ridiculous. Once he enters, all of Biden’s faults will be put on the table. And there are a lot to play with. If there weren’t, he’d have done better when he ran in past elections.

micah: From the WSJ writeup of the Quinnipiac poll:

The Quinnipiac poll found that 51% of voters have an unfavorable impression of her, her worst score ever on that measure. The poll also found that 61% of voters say she is not honest and trustworthy, another record low. On the honest and trustworthy question, that is up from 57% in a July Quinnipiac poll.

natesilver: Here’s the problem, Micah. Lots of people, political reporters especially, believe in momentum. If something goes from 50 to 45 percent, they assume it will keep going down, until it hits 40, 35, etc.

But empirically, the opposite is closer to being true. At least when it comes to polling.

If something goes from 50 to 45, it’s more likely to bounce back to 50 than to continue declining. Mean-reversion tends to be stronger than momentum. At least over the long term — the short term is sometimes a different story. But it’s the long term we should be concerned with, given that it’s still only August.

The Clinton who has a 42 percent favorability rating today isn’t really all that different than the one who had, I dunno, a 52 percent favorability rating at the start of the campaign, or a 48 percent favorability rating when she was running in 2008, or whatever. She is different than Clinton as secretary of state or first lady, because those are closer to being nonpartisan positions. So she can’t expect to see those numbers again, at least not while she’s a presidential candidate. But the odds are that her favorability ratings would revert to the mean by Election Day next year, which in her case means about 50/50.

hjenten-heynawl: Remember when there was talk about whether Chris Christie would get into the 2012 race? Or whether Fred Thompson would get into the 2008 race? Or Wesley Clark into the 2004 race? Those guys were tied or leading in the primary polling at the time. Biden’s best percentage so far has been 18 percent. He’s down nearly 30 percentage points to Clinton. Clinton is still in a ridiculously strong position.

natesilver: Yeah, I saw some article that offhandedly asserted Biden was polling exceptionally well given that he wasn’t in the race yet. Polling at 12 percent or 15 percent or 18 percent among members of his own party doesn’t seem that great to me for a guy who is vice president of the United States.

hjenten-heynawl: But we don’t have all the information. We believe Clinton is strong based on polling, money and support from party actors. If Biden were to enter, though, it says to us that he has a piece of information that we aren’t privy to. And this information is that Clinton is weak — for whatever reason. If he doesn’t enter, it’s a confirmation that she is strong within the party.

natesilver: Part of this is looking for verifiable evidence in an environment where the media has an interest in overrating how competitive the Democratic race is.

By most objective measures, Clinton is doing really well in the nomination hunt. About as well as any non-incumbent candidate has been doing up to this point in time. So, on the one hand, we look at that data and it makes us skeptical that Biden will convince himself to run. On the other hand, it means we have more reassessment to do if Biden in fact does run.

micah: OK, let’s say Biden gets in. How does he win? Does he come in guns blazing on email and trustworthiness? Does he claim the Obama mantle?

natesilver: How does he run or how does he win? I’d guess that his messaging would be rather cryptic at first. Because the way he wins is basically if Democrats decide that Clinton is too much of a liability because of her scandals. But Biden doesn’t want to come right out and say that. Debating Clinton on policy is also awkward, though, given that they have few real differences. And that, to the extent they do, one of them is going to be criticizing the Obama administration’s policy, which is an odd look for an incumbent party trying to win another term in office.

hjenten-heynawl: Let’s start with this: Clinton must perform disappointingly in the Iowa caucuses. If Clinton wins in Iowa by a convincing margin, this thing is going to take off. I don’t know how Clinton loses in Iowa, necessarily, but that’s where it needs to begin. Biden cannot wait until later states to take her on. Her money and momentum will be too great. So it’s Iowa or bust. Now, it could be that Sanders comes close in Iowa — it doesn’t have to be Biden, but he’s gotta do reasonably well.

natesilver: Yeah, I agree. I mean, one way Biden wins is if there’s some new scandal (or some new wrinkle to the email scandal) that’s so bad Clinton drops out. That’s sort of obvious, I suppose.

Short of that, it might come down to the timing. Say there’s some bad news for Clinton that drops a couple of weeks before Iowa. Iowa is taken as a referendum on her campaign, and she fails that referendum.

micah: And what happens to #feelthebern if Biden jumps in?

hjenten-heynawl: I think he continues on the path it was on. He’ll continue to get white liberals and that’s about it. I guess you could argue one way or another whether this slightly boosts his odds, but I think it doesn’t help him. If anything it could steal attention away from him as the anti-Clinton.

natesilver: Yeah, I don’t think Sanders’s support will be affected that much. At the margin, it might make it easier for him to win the plurality in a caucus state here or there. But Bernie will keep on Bernin’.

What I don’t think we’re likely to see is a case where the Clinton-Biden fight drags out for months and months, and then we’re all doing a bunch of delegate math, involving Clinton and Biden and Sanders, in May. As Harry said earlier, a Biden candidacy would either gain traction or collapse pretty quickly based on how it did in Iowa and New Hampshire.

hjenten-heynawl: Support for an anti-Clinton is either there or not.

micah: So on our initial question — “Could a Biden run help Hillary Clinton?” — we think the answer is: “No. And also, it probably wouldn’t affect Sanders much either.”

Is that right?

natesilver: A Biden run would be the worst news Clinton has had so far in the campaign. She’d still probably be the favorite, however.

Public Transit Should Be Uber’s New Best Friend

If Uber is worth its $50 billion valuation, it will have to do more than win over the market historically occupied by the taxi and limo industry — it will have to identify new types of customers.

The biggest potential market is among people who own their own cars: The average American household spends around $8,500 on personal vehicles per year; multiply that by 125 million households, and you have a market worth in excess of $1 trillion per year. Persuading even a small fraction of households to give up their cars for Uber could be very lucrative for the company.

But if Uber is to achieve its goal of becoming cost-competitive with car ownership, it may have an unlikely ally: public transit. A combination of (mostly) public transit along with some Uber rides can be affordable for a wider range of customers than Uber alone.

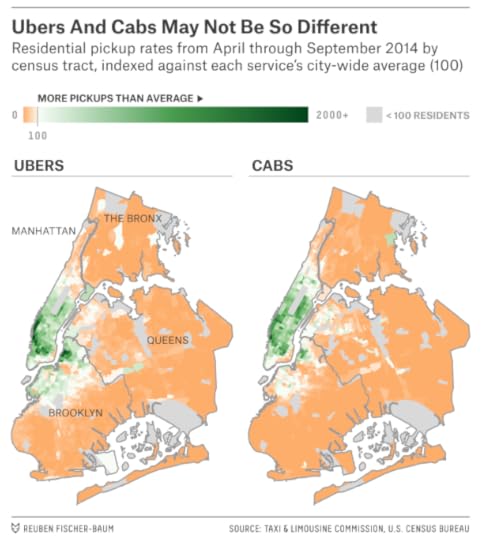

New York City is the biggest market for public transit in the country — in fact, about 40 percent of all public transit trips in the United States occur in the New York metro area. And as it happens, we have some very good data on how New Yorkers are using Uber, public transit and other services. Earlier this month, we published an analysis based on about 93 million Uber and taxi trips in New York from April to September 2014, including information about Uber trips that we obtained via a Freedom of Information Law request. That analysis focused mostly on the differences between Uber and taxi coverage: As compared with taxis, for instance, Uber use is proportionally higher in Brooklyn.

But in New York overall, there isn’t much difference between the people picked up by Uber and the ones who ride in cabs. Uber and taxis both disproportionately serve wealthy areas within Manhattan or just across the bridges and tunnels from it. What’s more, these customers usually live in neighborhoods with abundant public transit access also. In other words, the combination of public transit and for-hire vehicles is something that New Yorkers have been relying on for years.

Take a look at the maps we’ve produced below, which track pickups by Uber and taxis on a per capita basis, census tract by census tract.1 The data includes an adjustment for the ratio of residents to workers in each census tract, with the goal of identifying rides that originate from a person’s place of residence rather than where they work, shop, go to school or spend leisure time.2

As you can see, Uber and taxi usage have a lot in common. The correlation coefficient between per capita Uber use and per capita taxi use3 is 0.89, not that far from a perfect correlation of 1.

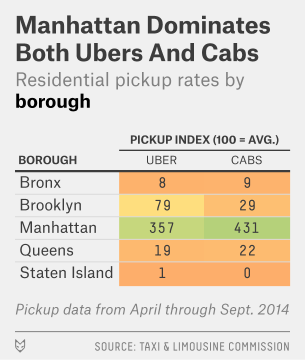

We can also consider these differences by various geographic and demographic categories on a scale where 100 represents average per capita residential usage for each service.4 Here’s a comparison of how often cabs and Ubers are used by borough, for example.

As of mid-2014, the average Manhattanite used Uber about 3.6 times as often as residents of New York overall, and taxicabs about 4.3 times as often. Remember, our method seeks to adjust for the fact that many of the pickups in Manhattan are from commercial rather than residential locations; without that adjustment, the differences would be even greater. The closest thing to an Uber borough is Brooklyn, where cabs were used 70 percent less often as in the city overall, but Uber rides were used just 20 percent less often. Otherwise, the differences between the services are quite modest. In Queens and the Bronx, Uber and taxi use is fairly proportionate. In Staten Island, which is not connected directly by road to Manhattan, both Uber and taxi use is extremely rare.

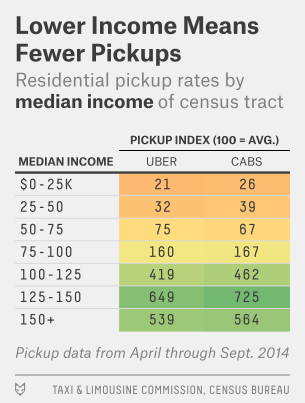

But while there are some geographic differences in Uber and taxi usage, the demographics of their passengers seem to be mostly the same. In particular, passengers of both services are highly concentrated in wealthier areas. A resident of a census tract where the median income is $135,000 per year takes about 20 times more Uber rides and 20 times more taxi rides than one where the median income is $35,000, for example.5

This is a reminder that a taxi or an Uber is a big expense. Given the current fare schedule for yellow cabs, a 5-mile journey in a New York taxi might cost $20, including a reasonable tip and depending on traffic. (Pricing for one of Uber’s lower-cost services, UberX, is pretty similar.) Subway rides cost $2.75, by contrast — about $17 less. If traveling by taxi saves a passenger 15 minutes — a possibly generous estimate given that the subway is sometimes faster than a taxi stuck in traffic6 — that means she must value her time at $68 an hour or more to make taking the cab worthwhile, equivalent to her earning an income of about $140,000 per year from a 40-hour work week. For a well-paid lawyer or banker, that’s nothing, but the median household income in the city is closer to $50,000.

The subway is the quintessential New York mode of transportationHow big is the for-hire car market in New York? Our data set includes 93 million taxi and Uber rides over a six-month period in 2014. Double that and round up,7 and you get to about 200 million rides per year. By contrast, the New York subway provided 1.75 billion rides in 2014, about nine times as many. There were also almost 800 million MTA bus rides8 in 2014.

Public transit use, in contrast to taxi and Uber rides, is relatively egalitarian in New York. In census tracts where per capita income is $50,000 or less, 62 percent of workers commute by public transit; but so do 53 percent in tracts where per capita income is $100,000 or higher.

For a few upper-middle-class and wealthy New Yorkers, Uber and taxi service may serve as a substitute for comparatively poor subway service. For instance, taxis and Ubers are used especially heavily on the far west side of Manhattan between Houston Street and 59th Street, an area not currently well-served by the subway (although service will improve following completion of the No. 7 line extension). Taxi and Uber use is also high in areas with crowded subway service, like on the Upper East Side along the Lexington Avenue line9 and in Williamsburg along the L train.

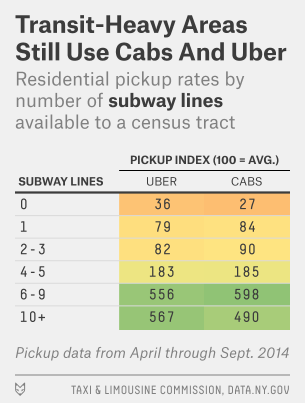

But for the most part, Uber and taxis provide service in places where public transit is a good option also. We collected data on how many subway lines10 are located within a quarter-mile of a census tract’s boundary line in any direction.11 In census tracts that have no nearby subway lines, taxis are used only 27 percent as often, and Ubers 36 percent as often, as in New York overall. Use of taxis and Ubers is markedly higher in census tracts with even one nearby subway line, and it continues to increase until you get to the handful of census tracts saturated with 10 or more nearby subway lines. The differences hold12 even if you account for the distance from Midtown Manhattan: Where public transit is poor, taxi and Uber service tend to be uncommon also.

Cars are a big deal, even in New YorkAll of this might seem counterintuitive: Why is taxi and Uber use high in neighborhoods where public transit is a good option? The reason may be that in neighborhoods where public transit has historically been a poor option, a personal vehicle is still the dominant mode of transportation. Car ownership is not as uncommon in New York as you might infer from media portrayals of life in Manhattan or well-off neighborhoods of Brooklyn. Instead, almost half of New York households own a car, and more than 10 times as many New Yorkers drive themselves to work as arrive there by taxi, according to the American Community Survey.

Put another way: Given the high fixed costs of vehicle ownership, the first and most important transportation choice a New York household makes is whether to own a car. Residents who go without a car may use some combination of public transit, taxis, Ubers and other alternatives (like bicycling and carpooling) to get where they need to go. In that sense, Ubers, taxis and public transit are complements to one another instead of competitors.

But transportation options are also constrained by a commuter’s income. Our data suggests that we might place New Yorkers into about five broad categories, based on their income and ease of access to public transit.

Group 1 — Low income, poor public transit access: In census tracts with no nearby subway line, 66 percent of households have access to a private vehicle.13 An exception among these neighborhoods, however, is those where incomes are below $35,000 per year: Car ownership remains low there. Given the high cost of living in New York, a $35,000 income is the equivalent of about $20,000 for an average American household, making even a clunker a stretch to afford. Families like these have no great choices.

Group 2 — Low income, better public transit access: Households in census tracts that have median incomes below $35,000 and access to at least one subway line are heavy users of public transit, making about two-thirds of their commutes to work that way.

Group 3 — Middle to high income, poor public transit: Your choice is pretty clear if you’re a New Yorker with relatively poor public transit access but enough income to afford a car. Like most Americans, you’ll buy a car. In census tracts with median incomes of $35,000 or more but with no nearby subway lines, about 72 percent of households have cars. These census tracts are concentrated in Staten Island and the eastern part of Queens, which are more suburban than other parts of New York City (in other words, more like the rest of the United States).

The last two groups are more interesting for Uber:

Group 4 — Middle income, average-or-better public transit: You might think that car ownership is concentrated among the upper class in New York, but this isn’t really true. Instead, car ownership peaks in census tracts with median incomes of about $75,000 per year. Part of this is because neighborhoods with the worst public transit access in New York tend to be middle class, and people in those neighborhoods are more likely to need cars.

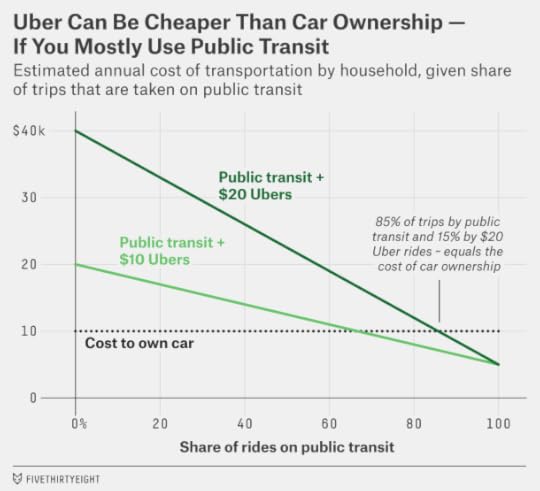

The most interesting case may be for customers who can conveniently make some, but not all, trips on public transit. Consider a household that makes about 2,000 vehicle trips per year, in line with the national average. (If that sounds like a lot of trips, remember the figure is per household and not per person.) It can either spend $10,000 a year on car ownership,14 or it can use a combination of public transit (at a cost of $2.50 per journey15) plus Uber and taxis.

If the household can make all its trips by public transit, then that’s by far the cheapest option. But suppose it cannot. How many Uber rides can it afford to take before owning a car becomes cheaper?

If Uber costs about $20 per ride — about what an UberX costs now for a 5-mile ride in New York in moderate traffic — then the household can make up to about 15 percent of its trips by Uber and the combination of Uber and public transit will remain cheaper than owning a car. On the one hand, that figure implies that the household still needs excellent access to public transit since it must make 85 percent of its journeys that way. On the other hand, 15 percent of 2,000 trips is still 300 Uber rides per year.

Uber is also introducing some cheaper services, such as its carpooling service UberPool. Suppose that the price of an Uber ride could be halved, to $10 per ride. In that case, this household could take about a third of its trips by Uber, filling in the rest with public transit, and it would still be cheaper than car ownership.

But there’s a long way to go before Uber becomes cost-competitive with car ownership without an assist from public transit. A car ride costs an owner in the United States $4 or $5,16 including both fixed expenses (mainly, the cost of buying the car) and marginal expenses like gasoline. Even Uber’s cheapest services like UberPool aren’t yet competitive with that price.

Analyses like this one which suggest that Uber is already often cheaper than car ownership depend, in part, on accounting for opportunity costs. You can potentially use your time more productively when someone else is driving you instead of when you’re driving yourself. But those opportunity costs vary from person to person depending on how much people value their time.

Group 5 — High income, average-or-better public transit: For the time being, indeed, the principal consumers of both Uber and taxis in New York are upper-income passengers who can afford to value their time highly. Relatively few of them own cars, perhaps because it’s more convenient for them to be driven around in a taxi or Uber than to drive themselves. However, it’s likely that many of these customers also use public transit frequently, especially when (like during rush hour) the subway is potentially faster than an Uber or a cab.

Put another way, Uber’s market in New York right now consists mostly of people who want to save time, or at least save productive time (you can make a private phone call in your Uber when you can’t on the C train). From Uber’s standpoint, that’s good and bad: It’s an audience with lots of money to spend, but also one that cabs and other ride-sharing services are vigorously competing for.

But there’s a much wider potential audience if Uber can also reach middle-class customers who want to save money. Perhaps in the distant (or even the not-so-distant) future, Uber can build its own version of “public” transit, making rides so cheap that they cost less than the $4 or $5 that Americans now pay, on average, to make a trip in their personal cars. In the meantime, it might have more success among “car-cutting” customers who can use Uber along with public transit. That might mean Uber’s growth is concentrated more in cities like New York, San Francisco and Chicago — and in Europe and Asia — that already have reasonably strong public transit networks.

Carl Bialik, Andrew Flowers and Dhrumil Mehta contributed to this article.

Read more: Uber Is Serving New York’s Outer Boroughs More Than Taxis Are

August 26, 2015

Donald Trump Is Running A Perpetual Attention Machine

Earlier this month, I outlined Donald Trump’s “Six Stages of Doom” — the hurdles he’ll have to clear to win the Republican nomination. The first obstacle: Could Trump keep his polling numbers up when another storyline emerged that prevented him from monopolizing the news cycle? “For a variety of reasons, Trump isn’t affected much by negative media coverage — it may even help him,” I wrote. “But a lack of media coverage might be a different story.”

It’s too soon to say whether Trump has passed this first test. Partly because it’s August — almost half a year before Iowa and New Hampshire and way too early to read much into the polls — but also because the Trump show hasn’t stopped. He’s dominating coverage as much as ever.

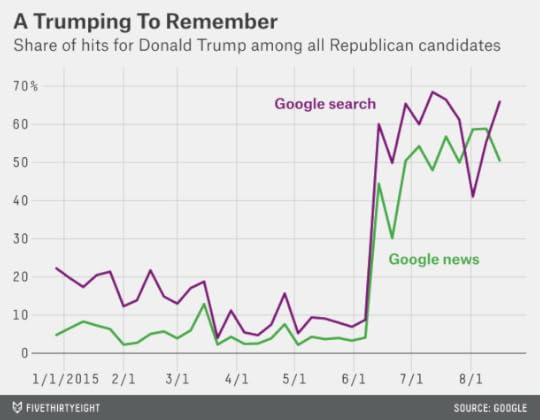

The chart above shows the share of news coverage and Google search traffic that Trump has received among all Republican candidates. (See here for the methodology.) The share of news coverage devoted to Trump has been fairly steady over the past month. Steady and very high, at 50 percent to 60 percent of all coverage received by the GOP field. In other words, Trump is getting as much coverage as the rest of the Republican field combined. But Trump’s Google search traffic is often just as high, or higher.

There’s one anomaly, though, which is the week of Aug. 2. That was the week of the first Republican debate, in Cleveland. That week, Trump received a comparatively low share of Google search traffic — “only” 41 percent. People weren’t any less interested in Trump after the debate, but they were more interested than usual in some of the other Republican candidates, especially Ben Carson, Carly Fiorina, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio and John Kasich, each of whom had among their best weeks of the year from a search traffic standpoint. So Trump’s share of search traffic fell in proportion to the rest of the field. Media interest in Trump was as high as ever, however: He represented 59 percent of the press coverage that week. Since then, search traffic for Carson, Fiorina and Cruz is a bit higher than before the debate but has reverted mostly back to the mean.

What’s interesting is how Trump seemed to go out of his way after the debate to ensure that he’d remain the center of attention, with his tirade against Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly (a feud that he’s since resurrected). That tended to drown out most of the coverage of whether, say, Fiorina or Kasich had gained momentum after the debate, perhaps preventing them from having the sort of feedback loop of favorable attention that can sometimes trigger surges in the polls.

I don’t know whether this was a deliberate strategy on Trump’s behalf. But if so, it’s pretty brilliant. Trump is perhaps the world’s greatest troll, someone who is amazingly skilled at disrupting the conversation by any means necessary, including by drawing negative, tsk-tsking attention to himself. In the current, “free-for-all” phase of the campaign — when there are 17 candidates and you need only 20 percent or so of the vote to have the plurality in GOP polls — this may be a smart approach. If your goal is to stay at the center of attention rather than necessarily to win the nomination, it’s worth making one friend for every three enemies, provided that those friends tell some pollster that they’d hypothetically vote for you.

Is it sustainable? In the long run, probably not. There are lots of interesting candidates in the GOP field, whether you’re concerned with the horse race, their policy positions or simply just entertainment value. Sooner or later, the media will find another candidate’s story interesting. Cruz has a lot of upside potential in the troll department, for instance, along with better favorability ratings than Trump and a slightly more plausible chance of being the Republican nominee.

But there’s not a lot of hard campaign news to dissect in August. Fend off the occasional threat by throwing a stink bomb whenever another story risks upstaging you, and you can remain at the center of the conversation, and atop the polls, for weeks at a time.

Read more: “Donald Trump’s Six Stages Of Doom”

August 21, 2015

This Is How Bernie Sanders Could Win

micah (Micah Cohen, senior editor): We’ve been pretty tough on Bernie Sanders here at FiveThirtyEight. He’s surged in the polling and drawn big, enthusiastic crowds, and yet we’ve written several articles largely dismissing his odds of toppling Hillary Clinton. Many Sanders fans have written us calm, kind notes arguing that Sanders has a chance. Not a “well, anything is possible” chance — a real chance to win the Democratic presidential nomination. So, today’s question: How can Bernie Sanders win? [This is an edited transcript of a conversation in Slack.]

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): I still think it needs to involve some “shock” (as an economist would define that term) to the Clinton campaign. Meaning, some substantially worse turn in the email scandal than what’s been reported so far. Hackers publish a bunch of top-secret documents culled from Clinton’s emails, for instance. Or a new scandal. Or a health problem.

In that event, Democratic elites would probably turn toward another establishment candidate. Most likely Joe Biden. But while I’m pretty sure that Sanders can’t beat Clinton head-to-head — he’s losing to her badly now, after all — I’m not so sure that’s true of Biden, etc.

I think Sanders vs. Biden, in a world where the Democratic establishment is in disarray because of a Clinton crisis, could be highly competitive. And Bernie’s organizational advantages — e.g., in the caucus states — could help him against a candidate who is getting off to a very late start.

hjenten-heynawl (Harry Enten, senior political writer): As I try to get on the good side of the Bernie Sanders supporters, let me start with what we know: Presidential primaries can be about momentum. You win Iowa, you win New Hampshire, and the sky’s the limit. You saw that with John Kerry in 2004 on the Democratic side. You saw that with Jimmy Carter in 1976. Carter, especially, was someone who sort of came out of nowhere — the outsider candidate, if you will. So the first thing that Sanders likely needs is to win the first caucus and the first primary.

micah: And that seems eminently possible, right?

hjenten-heynawl: Yes. Yes it is. Then — and this is the big thing — he needs to find a way to cut into Clinton’s support among African-Americans. Sanders is pulling in less than 10 percent of the black vote. Obama had about five times as much at this point. If Clinton continues to win 70 percent of the black vote, Sanders will likely get stopped in South Carolina. If, however, he can cut into that advantage, he could build a wave of momentum.

hjenten-heynawl: It’s important to remember that movement people aren’t necessarily the base of the party. Take a look at the recent CNN poll, for example: Clinton leads among self-identified Democrats 55-20 but trails among independent-leaning Democrats 39-37.

Clinton is doing very well among base Democrats, while Sanders is an outsider.

natesilver: Yeah, people need to stop confusing “the base” with “media and party elites that have big Twitter and Facebook followings.” By any objective measure, the Democratic base still really loves Clinton.

hjenten-heynawl: But let’s get back to South Carolina. There’s no party registration, so anyone can vote in the primary. It gives Sanders a shot if he can somehow pull in some of these outsider voters who might not otherwise vote in a Democratic primary.

natesilver: No way, dude. Hillary wins South Carolina even if things are going really badly for her. There was a poll that came out in Alabama the other day that had Clinton beating Sanders something like 81-10. Literally. It was like an Alabama football score against some terrible nonconference opponent.

hjenten-heynawl: 78-10. But continue.

natesilver: It’s not complicated. In a state where you have a lot of white moderates and a lot of black voters, Sanders does terribly.

INTERACTIVE: We’re tracking 2016 presidential primary endorsements. Check out the most important race before the actual race »

micah: Not so fast …

Our general thinking has been that Biden is only likely to enter the race in an “in case of emergency” situation. That is, Clinton’s campaign suffers a much more serious wound than anything inflicted so far. But we don’t know that. What if Biden jumps in in September or October? Doesn’t that help Sanders? Biden and Clinton split moderate and conservative Democrats (and perhaps black voters), and Sanders pulls through with the left wing of the Democratic Party?

hjenten-heynawl: Maybe, but I think Sanders’s best shot is to be the only real alternative to Clinton. Say this email scandal breaks further, and it’s too late for someone else to enter.

natesilver: I guess that’s where my thinking has changed slightly, Harry.

As I said earlier, I can imagine a case where Biden enters after a Clinton crisis and Sanders beats him.

micah: But you both seem to think that there is unlikely to be a scenario where Clinton and Biden are both in the race and both in decent shape?

natesilver: Well, most of the polls we’ve seen now have Biden in the race and have Clinton winning like 50-25 over Sanders, with Biden at 15 percent or so.

micah: But he’s not campaigning.

natesilver: OK sure, but he’s also a sitting vice president. Not exactly unknown. And Clinton has like 75 percent, 80 percent favorability ratings with Democrats. There’s just not much of a market for an anti-Clinton candidate. Except among white liberal Democrats, especially men, who just like Bernie better on the issues.

hjenten-heynawl: Yes, I don’t really see why Biden enters if he doesn’t think he can win. And he can’t think he can win if Clinton is in good shape. Remember, Biden isn’t some movement politician. He’s a 45-year veteran of Washington. He’s somebody who screams establishment. You don’t get in if there is an establishment candidate already that is in strong shape.

natesilver: I mean, it’s possible I guess that there’s a Clinton crisis that’s a 7.6 on the political Richter scale instead of an 8.5. And that Biden enters, but Clinton isn’t quite ready to withdraw. And Sanders emerges. Sure.

But the predicate for that is still a crisis for Clinton.

Also, even in that scenario, Clinton’s delegates might eventually go to Biden, or the reverse. Plus, Democrats have quite a lot of superdelegates, very few of whom are liable to support Sanders.

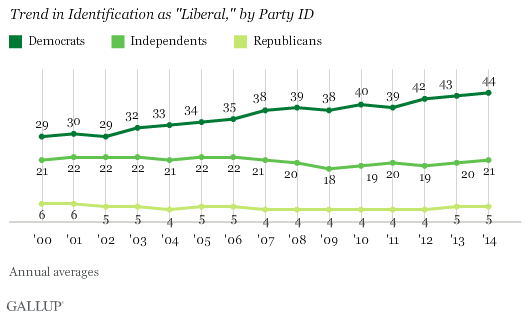

hjenten-heynawl: Let me say one thing that has changed in recent Democratic politics. If Gallup’s numbers are to be believed, there are more self-identified liberals than at any point in the last 15 years among the Democratic base:

And, of course, Sanders is doing best among self-identified liberals. So he has more of a chance this year than in past years.

natesilver: So, I agree that the left should be pleased with how Bernie is doing. I think his ceiling is a few percentage points higher than it might have been an election cycle ago. I just don’t think it’s particularly close to 51 percent in a head-to-head race against Clinton.

micah: So, yeah, let’s talk about that ceiling. Let’s forget Biden or an external shock for the moment. Who’s to say Sanders won’t just keep gaining support? Concern about inequality isn’t limited to the left wing of the Democratic Party, after all.

Where is his ceiling? And why? Can’t he persuade his way to the nomination?

hjenten-heynawl: His ceiling is as high as his ability to gain among blacks and Latinos. Look at this latest YouGov poll that has a pretty decent sample among black voters. Sanders is currently getting … 4 percent. Should I say that one more time? 4 percent. You can’t win a Democratic nomination getting 4 percent of the black vote.

natesilver: This is where a Sanders reader would write in and remind us that Obama wasn’t doing so well among the black vote early in the 2008 race.

hjenten-heynawl: This is where I would remind them that a number of surveys at this point had Obama gaining near 50 percent.

natesilver: And, also, that there are some other rather obvious differences between Sanders and Obama. Bernie Sanders might be a progressive, but he’s still a 73-year-old white dude.

micah: He’s not Lee Atwater, though. And his policy positions are right to appeal to non-white voters, right?

natesilver: I don’t know, Micah. I’m not speaking for black or Hispanic voters, but there are a lot of them who might say racial injustice is more at the center of America’s problems than economic injustice.

And non-white voters are sometimes extremely pragmatic. They’re concerned about grave problems that their families face today, and they aren’t necessarily looking for a socialist revolution.

hjenten-heynawl: I think that’s exactly right. Look at why someone like Gary Hart, Jerry Brown, Paul Tsongas or Bill Bradley hit a brick wall. It’s because of minority voters. They didn’t give two [expletive deleted] about what these liberal white alternatives were selling. I’d also point out that black Democrats are far more likely to identify as moderate or conservative (67 percent) than white Democrats (50 percent), according to the General Social Survey. That’s a mountain that Sanders needs to climb.

micah: OK, let’s channel the #feelthebern-ers again. … We get a lot of tweets/emails from Sanders supporters pointing to his huge crowds and the general level of passion/enthusiasm among his fans. Doesn’t that count for something? Aren’t those people more likely to vote and organize?

natesilver: Micah, you sound like Peggy Noonan.

micah: Hey, I’ve seen a ton of Sanders lawn signs!!! The vibrations are in Sanders’s favor!!!

natesilver: Look, I think his campaign is liable to be pretty good at organizing. That could win him a couple of caucus states against Clinton, who will be really good at organizing too, BTW. And it’s why he could prevail against a Biden, etc., if Clinton has to drop out. But so far, what we’re seeing isn’t complicated. About one-third of the Democratic electorate is white liberals. And there aren’t a lot of people going after their votes explicitly. So Sanders can draw big crowds in places with lots of white liberals.

hjenten-heynawl: Let’s talk about one strength that Sanders may have that I don’t think people quite realize the extent to which it helped Obama. A poll came out earlier this month from Idaho that had Clinton at “only” 44 percent. Obama won that caucus by 60 percentage points. He took 12 net delegates over Clinton — 1 more than Clinton won out of New Jersey, despite a ton more people voting. Clinton has never been particularly popular in the West. If Sanders can win some caucuses out there — such as in Idaho, Washington, Wyoming — he could rack up a decent delegate count (on net). Remember, Democratic primaries are proportional.

micah: And there are a lot of white liberals out there? But aren’t they more Gary Hart Democrats? Not exactly socialists.

hjenten-heynawl: I think it could be argued that Sanders’s appeal is as much about attitude as it is about policy — in the same way Trump is as much about attitude as policy.

natesilver: I’d argue against both of your arguments, Harry.

micah: Disagreement!

natesilver: And the reason is that it’s predictable as hell where Sanders’s support is coming from: white liberals, especially white liberal men. Whereas Trump’s support doesn’t line up that well with well-defined ideological groups. He’s not doing that much better with tea party voters than with other Republicans, for instance.

One thing that’s appealing for liberal voters about Sanders, I think, is that he’s pretty consistently liberal (or leftist if we’re being precise) on pretty much every issue. The equivalent of a European social democrat. Instead of being a weird mishmash of liberal-ish stuff.

The one possible exception is immigration, which won’t help him particularly among Hispanics.

hjenten-heynawl: I will say that 45 percent of the Montana primary electorate in 2008 was liberal. So there are liberals out there. And a caucus, I’d bet, would be somewhat more liberal.

natesilver: But, Harry, gaming out all the delegate math is sort of beside the point.

Right now, Sanders has 25 percent of the vote nationally. [Actually more like 20 percent.] It’s going to be concentrated more in some states than others. But it’s not going to be nearly enough for him to take the nomination.

He might have some advantage in caucus states, but that’s outweighed by Clinton’s edge with superdelegates. But, again, it’s beside the point until he gets to, say, 40 or 45 percent of the vote nationally.

hjenten-heynawl: If Democratic voters chose Sanders over Clinton, the superdelegates would go along (à la 2008), but I agree that until Sanders actually, you know, leads in a poll outside of northern New England, it’s beside the point.

natesilver: So, Harry, what are Bernie Sanders’s chances of winning the Democratic nomination? Give me a percentage.

hjenten-heynawl: OK, the Bernie people have gotten to me. The Clinton emails seem slightly more likely to take down Clinton than they did a few weeks ago, so I’m going to double Sanders’s chances to 2 percent.

natesilver: I’m at 5 percent.

So, I actually think he has better chances than you do, even though you’ve been taking his “side” in this little discussion of ours, which makes an interesting point about the way media tends to frame events like these.

I’d guess that a lot of reporters who we might otherwise criticize would agree with us that Sanders’s chances are low. Maybe they’d say they’re 10 percent instead of 5 percent or 2 percent, but low. But there are lots of news stories written in a tone to make it seem like Sanders’s chances are much better than 5 or 10 percent. All the reasons why he isn’t likely to win the nomination are contained in one “to be sure” paragraph. Whereas all the reasons why that 5 percent might come through make headlines.

hjenten-heynawl: Very true. “Same old” does not a story make.

micah: OK … next week we tackle: Why Jim Webb will be the Democratic nominee in 2016!

August 18, 2015

Is The Republican Establishment Losing Control Of The Party?

The 2016 Republican presidential primary field is unusually large and unusually unsettled, and the first debate earlier this month didn’t do much to change either of those things. So we gathered FiveThirtyEight’s political writers in Slack to talk about the state of the race. This is an edited transcript of the conversation.

micah (Micah Cohen, senior editor): Harry and Nate, a Fox News poll released Sunday found Donald Trump, Ben Carson and Ted Cruz leading the Republican primary race, and a lot of people are saying the outsider/angry wing of the GOP is ascendant. Is something going on? The Republican Party’s last two nominees came from its establishment wing. Is that wing losing its grip?

hjenten-heynawl (Harry Enten, senior political writer): I think it really depends on the definition of what is an outsider and an insider. We can look back to the 2012 cycle and see where things were in November of 2011. We had Newt Gingrich taking the lead from Herman Cain. Gingrich, Cain, Ron Paul and Michele Bachmann added up to greater than 50 percent of the vote, and Mitt Romney became the nominee. If I’m the GOP’s establishment wing, I’m far more concerned not with what the outsiders added up to, but that there is no insidery candidate who is doing particularly well.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Well, Harry, you just pre-empted the disagreement we were supposed to have. One thing Republicans had going for them in 2012 is that there weren’t a lot of establishment choices to pick from. Romney, obviously, then Tim Pawlenty, then (if you’re going by endorsements) the pre-“oops” Rick Perry might count. This time around, the establishment vote might be split five or six different ways. Of course, it will probably consolidate around one or two candidates. But it could take some time.

hjenten-heynawl: Well, that’s the question, isn’t it? Is it merely delayed and not denied? We already see some of that going on in the Ipsos polling where Trump gains when the contest is down to just him, Jeb Bush and Scott Walker, but Bush and Walker gain a lot more ground.

natesilver: Harry, I think we’re both bearish on Trump, in part, because as the field consolidates, he isn’t likely to pick up that much second-choice support.

micah: Wait a second — Trump has a quarter of the vote. Carson and Cruz together have another 20 percent or so, and not a single establishment candidate is in double digits (Bush has 9.9 percent in the Huffington Post’s Pollster average). Doesn’t that say something about the mood of the GOP electorate?

natesilver: Well, all the usual caveats apply to looking at polls in August. There’s a lot of window-shopping going on. And also — I’m sure Harry can expound on this point — Republican voters might not divide the field into “establishment” and “anti-establishment” camps as neatly as people like us might.

hjenten-heynawl: Right. Look back at 2011. You would have thought Romney was in trouble because every so often a new alternative would pop up — someone against the establishment. But the polling clearly showed that Romney was going to pick up his fair share of the support once the alternatives started falling away.

natesilver: Still, one thing that’s unambiguously different this year is that you have so many candidates running.

micah: Here’s an argument: Trump is such an unusual candidate — he’s crazier than a Gingrich or a Cain — that his leading the polls right now is indicative of something unusual brewing among Republican voters. And the GOP establishment might have a tougher time reining that energy in this election than in past cycles. And the post-debate Carson bump, even if it’s temporary, backs that up

natesilver: Maybe Trump belongs in a third category.

Moderate/establishmentVery conservativeTrumpmicah: So add to that the fact that, as Harry said, there’s no establishment candidate looking too good at the moment. If you’re Reince Priebus, aren’t you sweating a little?

hjenten-heynawl: I think 1996 can be instructive here. No candidate got into the 30s in either Iowa or New Hampshire. Eventually Dole emerged. But I think the difference again is that Dole was in a class by himself among the more “establishment” candidates. Walker, Rubio, Bush, Kasich and even Christie are going to divide a lot of this vote, and none of them look all that strong right now.

INTERACTIVE: We’re tracking 2016 presidential primary endorsements. Check out the most important race before the actual race »

natesilver: We keep coming back to the fact that there are 17 [expletive deleted] candidates, including eight or 10 who could be plausible establishment nominees.

micah: Couldn’t that mess up the normal consolidating process we expect to happen?

natesilver: You could draw some parallels to the 1972 Democratic race, when George McGovern won with establishment support split between Muskie, Humphrey, etc.

You could also point toward a lot of differences from 1972.

micah: Like?

natesilver: Well, first of all, both parties learned a lot from 1972 and the disaster that was the McGovern nomination. Secondly, McGovern was very, very good at understanding the delegate rules — he made the rules, in fact! I wouldn’t expect Trump to have mastery of those, I guess. Third, McGovern was at least a Democrat, whereas it’s not clear that Trump is a Republican at all.

micah: It doesn’t have to be Trump. Isn’t Ted Cruz basically the George McGovern of 2016? Or couldn’t he be?

hjenten-heynawl: But what makes us think that Ted Cruz is going to win?

micah: I don’t think he’s going to win. I think it’s more likely this year than in past elections that the establishment could lose hold of the process. Certainly they don’t have much control right now.

natesilver: Betting markets give Cruz 25-1 odds against winning the nomination. That seems — about right?

micah: That seems fair.

hjenten-heynawl: I mean there is no reason for them to go after someone like Ben Carson who is a smart, nice guy … and who happens to be black in a party that desperately needs to do minority outreach. But you think for a second that most party actors think Carson and his politically incorrect statements will get near the nomination? There isn’t a reason for people to be taken down yet.

micah: But my argument is that the party actors may not have as much power.

natesilver: My concern, if I’m Reince Priebus, isn’t necessarily that Ted Cruz or Donald Trump is going to win the nomination. It’s that an establishment candidate eventually does, but it gets ugly.

micah: What does “ugly” look like?

natesilver: OK, let’s posit three degrees of ugliness.

An actual brokered convention.The nomination is decided before the convention, but there’s genuine uncertainty about who the nominee will be after the last primaries.No candidate has technically clinched the nomination as of the date of the last primary, but the writing’s on the wall.hjenten-heynawl: (If there’s a brokered convention, I’ll eat dinner in Brooklyn for a month.)

micah: [Editor’s note: Harry hates Brooklyn.]

natesilver: Harry, what chance would you assign to each of those outcomes?

hjenten-heynawl:

5 percent10 percent25 percentnatesilver: So, we do have some disagreement. I think the chances are about twice that at each stage.

hjenten-heynawl: So you think we head into June 2016, and there’s still a centipede running around with its head chopped off?

micah: That’s a … metaphor. A chicken?

natesilver: I’d say there’s a 20 or 25 percent chance that there’s genuine doubt about the identity of the nominee in June. Yeah. But it’s category Nos. 1 and 2 that I’d be concerned about. Where, in essence, the party hasn’t been able to reach consensus until it gets in to the smoke-filled rooms.