Christopher Barzak's Blog, page 5

August 25, 2012

Writing with Leonora Carrington

After I was finished discovering Remedios Varo’s life and life work, I returned to the artist who had introduced me to her: Leonora Carrington. What had started out as a seeming fluke was becoming something slightly bigger to me. A friend of mine, Maureen McHugh, who is also one of my former writing teachers, once told me that writers write about their obsessions, when they’re doing it right. The things that consume them. And these artists and their work had begun to seem a bit like an obsession to me. The worlds they created resonated with me, and I wanted to find a way to live inside those worlds for a longer period of time than I could simply by looking at their paintings. So writing stories became the way I could engage with them more fully.

But it was also through the research into their own lives that I began to see a pattern emerging. A pattern where women artists were excluded from surrealist art circles, except as romantic attachments. But even then, attached as a girlfriend or wife, they weren’t seen as equals, regardless of the superior work they were producing. They were seen as hobbyists.

One of Carrington’s most famous paintings is known by various names. “The Giantess,” or “The Baby Giant,” and (my personal favorite), “The Guardian of the Egg.”

In the painting, a giantess with a cherubic face shrouded in golden wheat stands within the confines of a rustic village with the ocean tumbling behind her, Viking boats riding the waves. She appears to have just arrived on the scene, and within the cup of her comparatively small hands she holds an egg. Below her, villagers have arrived to combat her with pitchforks and guns. She’s clearly seen as a threat to their way of life, though she bears life itself—the egg that she holds—as its guardian spirit.

This was the image that I wanted to work with from Carrington’s prolific collection of paintings. And unlike Varo, I didn’t get a sense of continuity in terms of “world story” from Carrington’s work, so this was the lone painting that I intended to work with. It set me up for quite a different process in story-making. Unlike Varo’s work, where individual paintings provided me with protagonist, antagonist, setting, sub-character, etc, I would need to draw all of my story resources from one painting alone.

It made me think about my approach differently. I needed to think of the painting as a question. What’s occurring here? What does this scene depict?

The painting demonstrates the wealth of metaphoric imagery that Carrington used to explore her own strict and restrictive upbringing in an upper class industrialist’s household, where her father did whatever he could to obstruct her path to becoming an artist, which Carrington would always see as an obstruction particular to her being a woman who wanted to pursue a career that would lead her away from the manners and mores of her family’s way of life. But the painting also represents a broader concern with the generally small-minded, old-fashioned, rustic “villager” mindset, which holds fast to traditional roles for men and women. The appearance of the giantess on their shores is a perceived threat to their lifestyle, which has surely prepared them more to expect the appearance of a god rather than a goddess. But there she is, unable to be ignored, larger than life, right in front of them. In every single way, this painting felt like a metaphoric icon for Carrington’s own battle as a female artist within a culture that would confine her to pre-approved and pre-arranged social roles.

But she was too big for that. Way too big. If you look into her back story, she was quite the heroine of her own life. She ran away from home to join the surrealist circles in Paris at a young age, took up with Max Ernst, was listed as a dissident by the Nazis and fled Paris to Spain, where she was virtually imprisoned in a psychiatric hospital by her parents and treated with drugs that were later banned by authorities. A few years after her release from the hospital, she wrote down the experiences in a small book called Down Below.

Knowing a bit about Carrington’s life and how she reworked her autobiography into visual metaphors of magic, I decided to explore the arc of her story–a young woman who grows larger than life, larger than the roles that are available to her in her constrictive community–as a modern tale. So instead of rustic villagers meeting the goddess with their pitchforks and guns as she comes ashore, I wrote a story about a seventeen year old girl who is confronted by the many small minds of her suburban American community as she begins to grow into a Giantess and eventually reveals a secret to her brother, the narrator, about her true purpose in life.

I linked to that story in a previous blog post, but I’ll do so again here, in case you’d like to read one of the stories for free: “The Guardian of the Egg”. If you like it, I hope you’ll get the book and enjoy the other two stories, and the essay at the end.

In the near future, I’ll be posting about the third artist in this triptych: Dorothea Tanning.

August 22, 2012

Writing with Remedios Varo

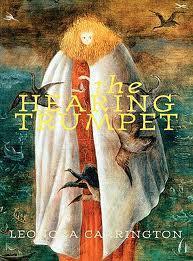

I stumbled upon Remedios Varo‘s art by accident. A happy accident. While I was in grad school (the first time, back in the early 2000s), I came across a surrealistic novel by Leonora Carrington called The Hearing Trumpet. The book’s cover was amazing:

So I looked into the cover artist’s background. It turned out that the writer of the novel had also painted the cover. I’d never heard of Leonora Carrington before, so I quickly began looking through the university library stacks to investigate further. It was in one of the books about her and her work that I discovered Remedios Varo, who was one of Carrington’s best friends. Before I knew anything else about Varo and her work, I knew her by the image of just one of her paintings that the writer of the book on Carrington had included when she made mention of their friendship. It was called “Creation of the Birds”:

And it was after I saw this painting that I quickly forgot about my research on Leonora Carrington. For a while at least.

I had never seen surrealist art that looked like this before: so precise, as if the artist was not so interested in tearing apart reality, but creating a new reality instead. Modernist surrealism was more about distortion and alienating effects. It walked the line of grotesquery, transfiguring reality and the received notions of reality we all have into a strange, often uncomfortable scenes of breakdown. I’m thinking of Dali at the moment, and his famous melting clocks in a desert landscape, for instance. An arid world where time no longer matters. That, in a way, was really typical of surrealist art at the time. But Varo, who was making art at the same time, didn’t seem interested in the breakdown of concepts like time or landscape or the human body. She seemed interested more in the creation of new notions of time, landscape, and in the invention of character and narrative in her paintings.

I was immediately hooked by her, and my research on Carrington went to the side temporarily, so I could seek out more and more of Varo’s work.

As mentioned, I was working on a Master’s degree at the time, and was in my second semester, taking a poetry workshop with the poet William Greenway, who had focused his workshop on the process of ekphrasis: the writing of poetry in response to paintings or visual art. I spent a lot of time that semester looking at paintings and writing (mediocre) poems in response. But I was really invested in the process I was learning. I was excited, even if my poems wouldn’t have seemed exciting to anyone who read them. I’m not a poet, and while I appreciate and love poetry, I always feel like I’ve been strait-jacketed whenever I’ve tried to write a poem. I’m more inclined to prose and narrative, and so, when it came to the final project for the class, I asked Will Greenway if I could write a short story in response to the visuals of Remedios Varo, rather than doing a series of poems. Will gave me permission, and it was then that I started to put together a story in a very different way than I ever had prior to that course.

Because Varo’s work is so character and place based, with inferred narratives clearly occurring within each painting, I felt like I could easily access those stories. I’d been looking at her paintings for several months by that point, and several revealed themselves to me as somehow being connected (though, really, all of Varo’s paintings feel connected to me, as if they are simply windows onto different personages and places in the fabulist landscape she created).

The first was “Creation of the Birds,” pictured above.

The second painting that felt like it was the inverse of “Creation of the Birds” was “The Star Catcher”:

In the first painting, it was clear to me that the Owl or Bird Woman of the painting was using celestial light to create, whereas in this one, the Star Catcher was imprisoning and collecting celestial bodies. They seemed to me like the perfect oppositional personages. They would be my protagonist and antagonist, respectively.

In the first painting, it was clear to me that the Owl or Bird Woman of the painting was using celestial light to create, whereas in this one, the Star Catcher was imprisoning and collecting celestial bodies. They seemed to me like the perfect oppositional personages. They would be my protagonist and antagonist, respectively.

The third painting that I decided to utilize for the creation of my story was “Spiral Landscape”:

This is a small image, so I’m not sure how easily viewable it will be on-screen, but essentially it presented me with my setting. And because I’m often inspired by setting as more than just the background wallpaper of a story, but as a thematic or sometimes conflict-driven aspect of narrative, I was attracted to “Spiral Landscape” as a potential embodiment of the conflict of cyclically toxic relationships, which the story presents. Opposites like the Bird Woman and The Star Catcher do attract from time to time, and they tend to have explosive relationships and histories that are hard to escape. The setting for these two characters would itself become part of their conflict. (I also just thought it would be pretty cool to live on a spiral shaped island).

This is a small image, so I’m not sure how easily viewable it will be on-screen, but essentially it presented me with my setting. And because I’m often inspired by setting as more than just the background wallpaper of a story, but as a thematic or sometimes conflict-driven aspect of narrative, I was attracted to “Spiral Landscape” as a potential embodiment of the conflict of cyclically toxic relationships, which the story presents. Opposites like the Bird Woman and The Star Catcher do attract from time to time, and they tend to have explosive relationships and histories that are hard to escape. The setting for these two characters would itself become part of their conflict. (I also just thought it would be pretty cool to live on a spiral shaped island).

So I had a setting and two characters with a relationship problem, which might have been enough. But I wanted to do more with it. I wanted to inject something into the narrative that also was indicative of modernist surrealism and the culture that surrounded it at the time. Since I was going to write about an essentially bad romance and relationship issues, I thought it might be fun to dig into psychoanalysis, Freudian thought, etc, which was so prevalent in the circles these artists ran in. And luckily, I discovered the fourth painting that I would work into the fabric of my story when I saw Varo’s “Woman Leaving the Psychoanalyst”:

I loved the idea of leaving a psychoanalyst with his head (head shrinking), his thoughts, his interpretations of your problems, rather than your own. In the painting, the woman’s hair is completely twisted, and she’s about to drop the psychoanalyst’s head (as I interpret it) into a well. Good riddance. I didn’t utilize this painting in a direct equation in my story, though. I placed the Bird Woman instead in this position, and created a third character, the Psychoanalyst, who she seeks help from to resolve her relationship issues with the Star Catcher. He serves to be a bit of a comic character in my story, and a good “extra” that allowed me to get outside of the Bird Woman’s interior space every now and then, as he literally becomes a “talking head” in my story.

I’d never conceived of a story in this way before, and it was really one of the most fascinating processes I’d ever gone through at that time in my experience as a writer. I’d been used to writing from within my own interior/emotional imaginative landscape. This process compelled me to absorb someone else’s world, to inhabit it, to figure out how it might “play” in a prose narrative. I still need to invent, but I had to work with materials borrowed from a visual artist.

A picture is worth a thousand words, they say, and I discovered that was pretty much true, though sometimes a picture can take more than a thousand words. The story I made, “The Creation of Birds” (just a bit different from Varo’s original title), was a bit over six thousand words in length, made from these four paintings filtered through my imagination.

Note: I’ll be back in a couple of days to talk about Leonora Carrington, who I returned to after my research into Varo.

August 21, 2012

The Birthday of Birds and Birthdays

Birds and Birthdays has officially released into the wild. It’s been available directly from the publisher for the past couple of weeks, but will be appearing in other marketplaces now, like Amazon.com (where they say it’ll take 1 to 3 weeks to get the book, but that’s only because they’ve just recently placed orders for stock with the publisher themselves).

Surprisingly and already, the book has received its first review yesterday as well! It’s over at Tor.com, and it’s a good one. So if you can’t take my (very biased) word that the book is good, take this reviewer’s.

I’m excited to have this book made real. For a long time, I’d thought it would be very unlikely to find a publisher for it, even a small indie press, who might be interested in a collection of three short stories and one essay, centered around the surrealist art of three women from the early half of the 20th century. But while that was a realistic doubt, it proved not to be true.

For the next few weeks, I’m going to be occasionally blogging here and in some other places about the book, its conception, the process I went through in researching and writing of each of the stories, the artists whose paintings inspired these stories, and how I went about organizing the book itself. It’s a small book, just a little over 100 pages, which seems as small as a grain of sand in a world where hugely huge epic page-turners pound the pavement around it. But I’ve always been fond of small things, the contained and hermetically sealed worlds of snow globes and dioramas, and I know there are folks out there who things like this too. So I’m hopeful this small book might reach their attention, despite the clamor and bustle of the giants lumbering around it.

If you’re interested in reviewing the book, contact me by email and I’ll see about getting a copy into your hands. And if you read and enjoy the book, and feel so inclined, please help me tell other people about its existence. Share links to it on your social networks, review it on Amazon or Goodreads or other places. I appreciate any help my readers can lend me.

In a day or two, I’ll begin posting about the topics I mentioned above, but for now, if you want a sneak peak at one of the stories in the book, you can read the second story, “The Guardian of the Egg,” for free at The Journal of Mythic Arts, where it was reprinted several years ago. That story was written in response to a painting of the same name by the artist Leonora Carrington.

And be prepared for a giveaway soon, too.

Happy birthday, Birds and Birthdays.

August 3, 2012

Birds and Birthdays Availability

Just a quick note to let everyone know that my new book, Birds and Birthdays, is available at the moment directly from the publisher, Aqueduct Press. The book will be available via other outlets in the near future, and will also be available as an e-book, but if you’re looking to get a hold of the physical copy now, you can procure it by way of this link to the book’s page on the publisher’s website.

I’ll be back around when the book is out in full force and making the rounds. If you’re a reviewer interested in reading the book for review on your website or blog, please feel free to contact me by e-mail (christopherbarzak AT gmail . com). I only have limited copies, though, so requests from reviewers with larger readerships will have to take precedence.

Thanks so much! More soon!

July 15, 2012

Birds and Birthdays Cover

It’s finally here, the cover for Birds and Birthdays, the 34th volume of Aqueduct Press’s ongoing Conversation Piece series.

The design is a standard for the Conversation Piece series, but the image on the front cover is one made by the artist Kristine Campbell (you can find more of her work at her website by clicking here). It’s really such an honor for me to have this particular image as the cover for this particular book, because Kristine and I go back a ways, back to the year 2000, when both of us were working as library assistants in Lansing, Michigan. I was a writer who hadn’t really published a lot of writing yet, and Kris was an artist who had made quite a lot of art and had had a lot of exhibitions around the country and in other countries, too. Kris let me see some of her work at one point, and I immediately fell for it. She has this amazing ability to match up different kinds of textures and styles into this surreal fusion with an underlying mythic power. Back then, she had this long hanging that was made almost like a quilt, and it featured this red dress that was one of her obsessions at the time. I wasn’t able to afford it, though, and eventually, in 2001, I moved back to Youngstown, Ohio, wondering if I’d ever come across Kris and her art again.

Thanks to the internet, in particular social networks, that became a mundane possibility, keeping in touch with old friends. After I sold this little book to Aqueduct Press, I happened to see new images of Kris’s art appearing in the feed of my Facebook, and when I saw this one, I stopped, dropped, and rolled.

It was really perfect in ways that won’t be apparent until you read the stories in this collection (and I do hope you read them, you wonderful person reading this post at this very instant). The image is called “Birds are Not the Target” but for this book, this image hit the bullseye.

The physical book will be available in mid-August, and the e-books will be available in September. Once the book releases, I’ll be doing some more posts about the book, the stories, the essay, the artists, and how I put this particular collection together. I’ll catch you all then.

Thanks for reading,

Chris

July 9, 2012

Andre Norton Award Jury Duty

While I already announced this on Facebook and Twitter , I thought I should mention it here on my blog, too, in case someone out there doesn’t keep up with my doings in the socializing networkings of the internet.

While I already announced this on Facebook and Twitter , I thought I should mention it here on my blog, too, in case someone out there doesn’t keep up with my doings in the socializing networkings of the internet.

I’ll be serving as a juror for the 2012 Andre Norton Award, which honors outstanding science fiction and fantasy Young Adult and Middle Grade books. Feel free to contact me by email if you have recommendations!

Official announcement from the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America follows:

The 2012 Andre Norton Award committee has been chosen, and will begin accepting books for consideration. Any young adult/middle grade prose or graphic novel first published in English in 2012 is eligible.

The judges are:

Victoria McManus (chair)

Christopher Barzak

Merrie Haskell

Eugene Myers

Carrie Vaughn

The committee will consider all submitted young adult and middle grade books until January 31st, 2013. The award will be presented at the 48th Annual Nebula Awards Weekend in San Jose, California, on May 18.

For submission information, please contact Victoria McManus at: [email protected]

The Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy, named to honor prolific science fiction and fantasy author AndreNorton (1912–2005), is a yearly award presented by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) to the author of an outstanding young adult or middle grade science fiction or fantasy book published in the previous year. The award was established in 2005 by then SFWA president Catherine Asaro and the first SFWA Young Adult Fiction committee and announced on February 20, 2005. The first Norton Award (for the year 2006) was bestowed during the Nebula Awards ceremonies on May 11–13, 2007.

July 5, 2012

Birds and Birthdays Cover Copy

Just received the cover copy for BIRDS AND BIRTHDAYS, which will be out next month (already!). Here’s the publisher’s book description:

Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning: three of the most interesting painters to flourish in male-dominated Surrealism. This is Christopher Barzak’s tribute to them: three stories and an essay that enter into a humane surrealism that turns away from the unconscious and toward magic.

Sometimes the stories themselves seem to be paintings. Sometimes painter and writer may be characters, regarding each other through a painful otherness, talking in shared secrets. Barzak’s stories are huge with the spacious strangeness of worlds where there is always more room for a woman to escape her tormenters, or outgrow an older self. Here we find:

A bird-maker and a star-catcher whose shared history

spills over into the birds and the stars themselves.

A girl who outgrows her clothes, her house, and finally

her town—and leaves to find her body a new home.

A landlord, whose marriage, motherhood, separation,

sexual exploration, and excursions into self-portraiture

all take place within a single apartment building.

In “Remembering the Body: Reconstructing the Female in Surrealism,” Barzak comments on the images that inspired these stories and discusses his own position as a writer among painters.

I can’t wait to hold the book itself in my hands.

Cover image to come!

May 17, 2012

News for a new year

I am as always a spotty blogger on this website, but I try to pop in when I have something I feel compelled to say (as per my last blog post today) and when I have some news to deliver. This post is some news.

If you follow my Facebook or Twitter pages, you’ll already know the first bit, which was announced a couple of months ago now, I think:

In August I’ll be publishing a very short collection of three stories (plus one essay!) called, Birds and Birthdays, which will be produced by L. Timmel Duchamp at Aqueduct Press, a press I’ve always loved and for which I never thought I’d have a project that fits their mission, and then I surprised myself with a small book that does fit in. Birds and Birthdays collects three stories–”The Creation of Birds,” “The Guardian of the Egg,” and “Birthday” all of which are my fictional narrative responses to the surrealist art work of the painters Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and Dorothea Tanning, respectively. Along with the tiptrych of stories will be an essay entitled “Re-membering the Body: Reconstructing the Female in Surrealism” that provides a context for the women surrealist artists who were working in the Modernist period of Surrealism, when the men were exhibited but the women were excluded from public showings and thought of as mere attachments to their artist boyfriends or husbands or friends.

These artists have been a huge, huge influence on my writing, despite their work being visual, for years now. I am so happy to have these three stories collected in one place finally (two had been published in separate anthologies in the past decade), along with the essay, as they were intended.

My other big news is that I’ll be publishing a full-length collection of short stories called, Before and Afterlives, with Lethe Press in March of 2013. The table of contents will most likely collect around twenty stories I’ve published over the past decade, all of which revolve around characters just on the precipice of great change in their lives, or afterward–sometimes long after, beyond the grave.

I started out writing short stories before ever trying to tackle a novel, and the short story is still a favored form for me. I am so grateful and excited to bring these two collections out in the coming months, after many years of endeavoring to make them. I hope they’ll find a warm audience waiting for them.

Thanks,

Chris

Life on the lowest setting

Imagine life here in the US — or indeed, pretty much anywhere in the Western world — is a massive role playing game, like World of Warcraft except appallingly mundane, where most quests involve the acquisition of money, cell phones and donuts, although not always at the same time. Let’s call it The Real World. You have installed The Real World on your computer and are about to start playing, but first you go to the settings tab to bind your keys, fiddle with your defaults, and choose the difficulty setting for the game. Got it?

Okay: In the role playing game known as The Real World, “Straight White Male” is the lowest difficulty setting there is.

Please read his entire post, because what I’ll be doing here is furthering some of the conversation John raised, and which my friend Meghan McCarron already furthered (after she and I nitpicked with certain aspects of John’s argument on Twitter, and John said he’d be happy to have other folks take the ball and run with it).

One of Meghan’s additions to John’s metaphor for privilege in the game of life was this:

Finally, at the end of the post, Scalzi points out that one doesn’t “choose” one’s own setting – it’s chosen by the computer, and that receiving the easy setting is a stroke of luck. That’s a powerful message – that we did nothing to deserve our privilege, and the fact that we have it is in fact meaningless – but ending there strikes me as a missed opportunity to explore an essential aspect of privilege: its invisibility to those who have it.

All too often, Straight White Men do not see that their setting is easier, and they assume that those struggling against bigger challenges are simply poorer players. At first this is innocent – the Straight White Men are focused on surviving the game themselves, after all. They didn’t design it. But the “easy” setting’s invisibility breeds arrogance, not the humility necessary to acknowledge that you’re “winning” the game because a. the game is easier for you and b. the game itself is designed to benefit you most. The fact that privilege robs us of empathy and humility is nearly as poisonous as the advantages it brings, because humble, empathetic people would not gleefully skip through difficulty while leaving others to suffer.

I wholeheartedly agreed with Meghan’s furthering of John’s metaphor. Part of the problem with privilege is that, when you have it, it’s almost invisible. The same way you might not realize what your voice sounds like until you hear it played back in a message–it seems like it belongs to someone else, unless of course you’re used to hearing your own voice played back to you.

Since Meghan had brought up what had been, for me, a salient defining point about privilege that had been left out of John’s metaphor, I was not going to write my own blog post about it. Well done, Meghan! But then today I came across an update from John on his blog, in which he further discusses his definition of privilege by way of responding to some of the general reactions various commenters on his blog post shared. John is always spot on with so many things–he’s a smartypants, for sure–but one piece of his extended discussion of the Life on the Lowest Setting blog post was a sticking point for me. Here it is:

3. Your description should have put wealth/class as part of the difficulty setting.

Nope. Money and class are both hugely important and can definitely compensate for quite a lot, which I have of course noted in the entry itself. But they belong in the stats category because wealth and class are not an inherent part of one’s personal nature — and in the US particularly, part of our cultural sorting behavior — in the manner that race, gender and sexuality are (note “inherent” here does not necessarily mean “immutable,” but that’s a conversation I’m not going to go into great detail about right now). You can disagree, of course. But speaking as someone who has been at both the bottom and the top of the wealth and class spectrum here in the US, I think I have enough personal knowledge on the matter to say it belongs where I put it.

This is where he sort of lost me (only partially, and on this one issue, to be specific). John had been defining privilege and how some people start out in life (or the roleplaying simulation game) with various benefits due to race, gender, and sexuality, which is all true. We don’t have terms like “the glass ceiling” to describe women’s perpetual inability to break through to the top of their various professions as easily as men for no reason, and we know that women still generally make less than men for doing the same work in many professions. We know that many GLBTQ people are not protected in their workplaces (or outside of them), and we know that systems like Affirmative Action were created to combat an entrenched system of prejudice and bias that had withheld opportunities for people of color. These are no-brainers (except for, I’m sure, people who have their ideological blinders on–hello, Privilege). But John’s dismissal of wealth/class as categories that affect one’s privilege because wealth/class in his estimation is not part of our “cultural sorting behavior” which might determine whether a person receives more privileges in the game of life than others. He discounts wealth/class because it is not “an inherent part of one’s personal nature.”

But this is not true.

First, I need to take apart John’s wealth/class hybrid category. These are two different things. Wealth is material goods and knowledge resources and access to social networks. Class is a cultural identity steeped in more than resources such as those, though it is intimately connected with those items that define wealth.

Class is something different than wealth. It’s a cultural identity that is connected in some cases to wealth but is not defined entirely by wealth alone. Socioeconomic identity is constituted by various social class values, attitudes, and mannerisms. It is something that we are judged on every day, just as an African American or a GLBT person or a woman faces judgments based on their identity every day. I know this because I come from a working class background, and though I have “risen” into the middle class, I do not feel as much a part of the middle class because I have a certain amount of money in the bank or more social networks at my fingertips as I do a part of the working class, which defines how I see the world. Though I crossed out of my working class background into a middle class life, the way that I learned to see the world, and to think of how the world saw me, is still with me. Rings on a tree don’t go away just because new layers grow over them. They’re there, inside, the heart of the tree really.

I have a friend who once told me about a study her Harvard classmate once participated in, where the social scientists observed the differences between working class educational institutions and private upper middle or upper class institutions. One of the clear differences, she told me, was that in the private upper middle and upper class institutions, the students were being taught how to conceive of ideas, how to execute them, and how to direct others in helping you execute your plans. But in the working class institutes, the students were being graded on how well they followed directions. Or, in essence, they were being trained to be the followers–the worker bees–for those students learning how to direct them.

That story was told to me probably a decade or more ago. In the years after I heard it, I finished a Master’s degree at the same university where I received my Bachelor’s degree–a university that is technically labeled as a research institution but generally behaves as a community college, because of the nature of the region in which I grew up: mostly working class, unprepared for college life. Youngstown State University offered (and still offers) heaps of remedial course work that most research institutions leave to community colleges surrounding them to do, because there were few other educational institutes in this region that could fill that role at the time. It’s odd, really, for a person to receive both undergrad and graduate degrees from the same institute–if you’re planning on being an academic, it “looks better” if you move from institute to institute, which can broaden your knowledge based on each institute being different from one another and offering different tracks and themes of study. But I had done both, because I didn’t know that at the time, and because I believed that I couldn’t succeed at another university–as a student, I’d overheard some professors talk about the nature of the working class student body, and how they’d never do as well in other settings. This hurt, but I do think there is truth to it, due to unpreparedness many working class students face. We haven’t been taught to be active learners, after all. We’ve been taught to follow directions. To do what others tell us.

After I finished my MA, I moved to Japan for a couple of years to teach English. This was a huge event in my life. I had lived for a short time in Southern California and for a couple of years in Lansing, Michigan, but the majority of my life had been spent in the general region where I’d grown up. I’d moved from the country to the town, but the town was an old, dying steel town, and it was small. A decent stepping stone for a kid who grew up on a farm learning how to break beef cows to lead behind him with a rope halter. It provided me with something different, but not completely out of my realm. Going to Japan, though, changed my life in incredible ways that I hadn’t even understood were possible, and most likely I didn’t understand those possible changes because I had grown up in such an isolated working class environment, and one of the things about that culture is this: we don’t tend to travel. Some people say it’s because we don’t want to leave what we know, and there is some truth in some cases to that, but it’s also because travel costs a lot of money, and working class people don’t have a lot of that.

So how could I have known just how much travel could change a person’s life, since I hadn’t done a whole lot of it, and what travel I had experienced had been minimal and in not-so-different-places in the U.S. from what I knew (Lansing, Michigan, for instance is an old industrial town that lost a lot of its industry too)?

While I was in Japan, I finished a novel, started a second one, learned a second language, and through the good fortune of having been a published short story writer that a Japanese translator of fiction recognized when I began to blog about life in Japan, I began working part time for a publishing company in Tokyo. The translator had reached out to me through email and brought me to Tokyo for dinner and conversation, and eventually he began finding work for me in his company.

This is all necessary background, trust me.

One evening, late into my two years in Japan, my friend Jodi and I went to a town festival, where we met a group of other ex-pats who were teaching English in nearby towns, and we hung out with them for a while. One of these other foreigners was a 23 or 24 year old African American male who had just graduated college and moved to Japan. We got to talking. He’d grown up upper middle class in Cincinnati, gone to a private school in New England, then did his undergrad degree at an Ivy League university, Brown. At one point in the evening, he told me he’d really come to Japan not to teach but to eventually get a job in a Tokyo publishing house. He had a plan, he said, and figured he could find work in one within a year. His dad knew someone who worked in publishing there, he said. He had an in. And also, he said, there’s always a Brown student who worked at this one company–they sort of held the position for a Brown student, in his description, which for all I know could have been completely inaccurate, but how would I know? No positions are reserved for YSU students, but maybe they are for Brown students? Or for students from other Ivy League schools. When I eventually told him that I was working part time for a Japanese publisher, he seized on me and shook me down for any information I could supply him, and asked whether or not I could get him work. I told him what I could, and said that I’d see, but that I was mainly only working by way of my personal contact.

Later, when Jodi and I went home, I grew upset and started to rage and storm a little bit about that guy. Jodi got me to talk about why I was so upset. Before I’d started talking, she was feeling me out, trying to see if she could touch on what I couldn’t say. She assumed it was because I thought all of the things that guy had received as he grew up seemed unfair. But really it wasn’t because of that. It was because I realized that night that he expected so many things with great confidence, and talked about his achievements with a grandiosity that was completely foreign to me. I didn’t expect much out of life. I was worried, by all accounts in my blog records of that time, that I couldn’t ever return to America because I hadn’t been able to find work there prior to leaving (I left America not because I had some kind of geek-on for Japanese culture, but because it was where I could find work), and I expected that that would never change. What I realized that evening that upset me so much was that I HAD achieved certain things in my life, but I discounted them all as good fortune that had befallen me, or as hands-up others had extended me. I didn’t see any of my achievements or successes in life as belonging to me, being rooted in my own endeavors, in my own inherent abilities. Here was this other guy living in Japan, doing the same thing I was doing, teaching English, but he’d chosen to go there because of his interests, whereas I’d gone there because I needed work and couldn’t find any back home.

I was self-effacing, which is a trait of many working class people. No, no, not me. Please don’t pay attention to me. I’d been taught to be invisible, and whatever I have I have by the grace of god or my benefactors/employers, etc. I had absolutely no confidence in my ability to change my life purposefully. Any good thing in my life “happened to me,” in my worldview. It’s not for nothing that working class people generally rack much of their lives up to fate, luck, chance, or other religious/cosmic forces. There’s a lack of agency for most working class people’s personal natures, and that is built into their identities culturally. It’s as inherent as a boy performing what his culture expects from male gender performance, in order to fulfill his identity as a male, etc.

What I’d like to add to John’s and Meghan’s furthering of Life on the Lowest Setting, the metaphor of privilege as a function of how easy or difficult life is based on character aspects, is that class does indeed count. If you’re a highborn mage instead of a lowly farmer’s son who happens to have a small knack for casting magic, you’ll receive all the best teachers, all the best training in the arcane arts, will have access to all of the materials you might need to cast a spell, which can be quite expensive. Or likewise, if you’re a highborn knight, you’ll receive all the best armor and weaponry and training in arms and defense, whereas the pub master’s kid will mainly know how to throw a punch and will swing wild without any really access to training.

Those are material considerations–the wealth aspect, or knowledge resources–to which a person of a certain socioeconomic identity generally has little access.

But class cultural considerations can also severely restrict some people, by learning your place, by taking direction because that’s what you were rewarded for, rather than learning to plan and set goals, rather than being among people who value reading and education or even networking beyond one’s own family in order to have greater opportunities in the warp and weft of our social order. And these are inherent to one’s personal nature if you have grown up in those conditions.

We judge people by the way they talk. Most people where I grew up say, “I seen,” instead of “I saw,” for instance. And are judged to be rubes by others because of it. The style or manner of appearance is different–the deeply casual is the mark for most working class people. I still cringe at putting on a suit and tie, and in fact didn’t learn how to tie a tie until I moved to Japan, where I had to wear one every day at the school where I taught. Even simple things like that cannot be taken for granted as we suit up for our various roles in the game of life.

Class does matter. Wealth does, too, but class is an identity, an invisible identity in some cases, like mine. Many of my friends now say that they can’t imagine me having grown up on a farm, that I once took part in a 4-H contest to catch a greased pig when I was eleven, that I seem too intellectual and worldly for a background like that. They can’t put my past and my present together, because I’ve crossed over into their world, and I’ve learned their language and mannerisms, much as I learned how to speak Japanese. I can switch codes from the academic circles I work within to the circle of service industry oriented childhood friends who are waiting tables and retailing and fixing cars. And all of those features are part of my inherent personal nature, a personal nature that was nurtured in a working class environment in my formative years.

I’d add class to that list of identity categories that determines privilege.

February 6, 2012

Me at Better World Books

Another short post that actually points you to a longer post I wrote for Better World Books, a truly revolutionary online bookseller with an important mission. Several months ago, Better World Books featured my first novel on a list of books for readers who want to "travel around the world" via books.

I was surprised and excited to be named on a list that also featured Steinbeck and Fitzgerald! In this blog post at Better World Books, I meditate on why place is so important to my writing. Here's an excerpt of the blog post:

Place, I think, is the reason why One for Sorrow might have been selected for the list. As a writer, I'm inspired by the places I've lived and those I visit for any length of time that allows me to sink my roots into the soil for a bit, to draw on the stories that surround and infuse any particular patch of earth. My second novel, for instance, The Love We Share Without Knowing, is set in Japan, where I lived for two years teaching English in rural elementary and middle schools. If I'd never lived in Japan for that long, I might never have written a story set there. Some writers can write about anywhere, but I don't think they always capture the feeling or spirit of a place as a writer who has been somewhere in particular, or especially lived somewhere. They capture a setting, but not the place, and these are two different degrees of narrative, I think.

To read the entire post, click here.