Terri Windling's Blog, page 12

July 5, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Yesterday was the 4th of July (Independence Day) in America, so the tunes I've chosen are all from that beautiful, complex, and music-filled country.

Above: "Wayfaring Stranger," an American folk and Gospel classic, performed by the MacArthur-Award-winning musician and music historian Rhiannon Giddens. Giddens comes from North Carolina (where she was a founding member of the bluegrass/roots band Carolina Chocolate Drops), and now works internationally in a number of musical genres. In this performance she's accompanied by Scottish musician Phil Cunningham, filmed in Northern Ireland in 2017.

Below: "Black is the Color," a song found in the North American folk tradition as well as in the British Isles. (We listened to an Irish version here two weeks ago.) Giddens recorded it for first solo album, Tomorrow is My Turn (2015), backed up by her colleagues from Carolina Chocolate Drops and others.

Above: John Hiatt's "Crossing Muddy Water" performed by I'm With Her (Sara Watkins, Aoife O'Donovan, Sarah Jarosz) at the Greyfox Bluegrass Festival in 2019. The trio has released one album so far (See You Around, 2018), but each member has several fine solo albums and recordings with Nickel Creek (Sara Watkins) and Crooked Still (Aoife O'Donovan).

Below: "Boll Weevil," an old Delta blues song performed by singer, fiddler, and banjo player Jake Blount (from Rhode Island), whose work explores the roots of Black and indigenous stringband music. The song appears on Blount's first album, Spider Tales (2020).

Above: "Send Brighter Days" performed by the great American blues guitarist Eric Bibb (from New York City) -- accompanied by his wife, Ulrika Bibb, at their home in Sweden during the pandemic last summer. The song, with its roots in the American Spiritual tradition, was written by Eric Bibb and Malian griot Habib Koit��.

Below: "The Roving Cowboy/Avarguli (���������������)" performed by composer and musician Wu Fei (from Beijing) and clawhammer banjo master Abigail Washburn (based in Nashville). The song appears on their collaborative album Wu Fei & Abigail Washburn (2020), which merges American old-time music with Chinese folksong to demonstrate the connective power of music across disparate cultures. It's simply stunning.

Above: "There Used To Be Horses" by singer/songwriter Amy Speace (based in Nashville). The song is from her new album of the same name, released earlier this year.

After that heartbreaker, let's end with: "New Star" by Watchhouse (Andrew Marlin and Emily Frantz), a folk/roots duo formerly known as Mandolin Orange. It's from their new album of the same name, due out in August.

Happy Birthday, America.

The painting above is "My Shanty (Lake George)" is by Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986). Although she's now best known for her iconic paintings of New Mexico in the American south-west, O'Keeffe also spent part of each year back east with her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who had an apartment in New York City and a country retreat by Lake George in the Adirondaks. I recommend the updated edition of Georgia O'Keeffe: A Life by Roxana Robinson if you'd like to know more about this remarkable woman.

June 30, 2021

Myth & Moor (and Tilly) update

I'm afraid there's no post this morning. Tilly is having health problems, so I'm off to the vet again...and then giving her a gentle walk for being such a good brave girl. Please send healing thoughts to our sweet old hound. Myth & Moor will be back tomorrow.

Update on Friday: We're still dealing with tests, etc. with Tilly. She had a difficult night last night, and I admit we're worried. I'll be back as soon as I can be -- and I'll post news when I have it, as I know there's a lot of love for Tilly out there. We all appreciate it very much.

Update on Saturday: Good news! Tilly's tests are back and she's going to be okay. She does, alas, have a new health problem (alongside her other long-term condition), but with medication and care it, too, can be managed. This morning she was able to get up without help, and even managed the jump up to her blanket on the sofa with only a little assistance. That's real progress from yesterday. She's still shakey, and shaken, and wants us close, but she will get better. We're so relieved.

Update on Sunday: Tilly has regained her sense of humour, which is a very good sign. (That's a chew bone hanging from her mouth like tusk in the photo below.) After days of shivery misery, it so good to see her spirits lifting! What a plucky little soul she is.

Update on Tuesday: She managed a very short walk this morning. She's still wobbly on her feet and tires out pretty quick -- but she was so happy to be in the good green world that she was smiling the entire time.

Thank you again for your good wishes.

Art: An illustration from a Victorian-era book in the Royal Library. Artist unlisted.

Myth & Moor update

I'm afraid there's no post this morning. Tilly is having health problems, so I'm off to the vet again...and then giving her a gentle walk for being such a good brave girl. Please send healing thoughts to our sweet old hound. Myth & Moor will be back tomorrow.

June 29, 2021

On fairy tales old and new

"I shall never know which good fairy it was who, at my own christening, gave me the everlasting gift, spotless amid all spotted joys, of love for the fairy tale. It began in me quite early, before there was any separation between myself and the world. Eve's apple had not yet been eaten; every bird had an emperor to sing to and any passing beetle or ant might be a prince in disguise....Perhaps we are born knowing the tales, for our grandmothers and all their ancestral kin continually run about in our blood repeating them endlessly, and the shock they give us when we first hear them is not of surprise but of recognition. Things long unknowingly known have suddenly been remembered. Later, like streams, they run underground. For a while they disappear and we lose them. We are busy, instead, with our personal myth in which the real is turned to dream and the dream becomes the real. Sifting this is a long process. It may perhaps take a lifetime and the few who come around to the tales again are those who are in luck."

- P.L. Travers (About the Sleeping Beauty)

"The fairy tale, which to this day is the first tutor of children because it was once the first tutor of mankind, secretly lives on in the story. The first true storyteller is, and will continue to be, the teller of fairy tales. Whenever good counsel was at a premium, the fairy tale had it, and where the need was greatest, its aid was nearest. This need was created by myth. The fairy tale tells us of the earliest arrangements that mankind made to shake off the nightmare which myth had placed upon its chest."

- Walter Benjamin ("The Storyteller," Illuminations)

"The great archetypal stories notes provide a framework or model for an individual's belief system. They are, in Isak Dinesen's marvelous expression, 'a serious statement of our existence.' The stories and tales handed down to us from the cultures that proceded us were the most serious, succinct expressions of the accumulated wisdom of those cultures. They were created in a symbolic, metaphoric story language and then honed by centuries of tongue-polishing to a crystalline perfection. And if we deny our children their cultural, historic heritage, their birthright to these stories, what then? Instead of creating men and women who have a grasp of literary allusion and symbolic language, and a metaphorical tool for dealing with the problems of life, we will be forming stunted boys and girls who speak only a barren language, a language that accurately reflects their equally barren minds. Language helps develop life as surely as it reflects life. It is the most important part of the human condition."

- Jane Yolen (Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Childhood)

"The reason why fairy tales last is because they allow us to gaze at ourselves through a glass that is at once transparent and reflective. They give us a double gaze to see ourselves from the inside out and the outside in, and they exaggerate our roles just enough to bring into focus the little pieces of monster that grow on our hearts."

- Sabrina Orah Mark ("The Evil Stepmother," Paris Review)

"Raised as I was on the darkest, grimmest of Grimm���s fairy tales, I���ve always been very much aware of the dual nature of the world depicted in folklore and story. For every happy ending, there is an equally tragic one; children left to die in the woods; lovers parted forever; villains with their eyes pecked out by crows, or burnt alive; or hanged. Fairytale is a world away from the comfortable assurances of the Disney franchise -- and surely that was the purpose of those original fairy tales, devised as they were for an audience comprising mostly of adults; often very poor; people whose lives were cruel and harsh, and who would never -- even in fiction ---have accepted to believe in a world in which the shadows did not at least occasionally rival the light."

- Joanne Harris ("Fairy Tale Reflections #27," Seven Miles of Steel Thistles)

"If you read fairy tales carefully, you���ll notice they are mostly about people who aren���t heroes. They don���t have special powers, or gifts. Often they are despised as stupid, They are bullied, beaten up, robbed, starved. But they find they are stronger than their misfortunes."

- Amanda Craig (In a Dark Wood)

"This is the thing about fairy tales: You have to live through them, before you get to happily ever after. That ever after has to be earned, and not everyone makes it that far."

- Kat Howard (Roses and Rot)

"People who���ve never read fairy tales have a harder time coping in life than the people who have. They don���t have access to all the lessons that can be learned from the journeys through the dark woods and the kindness of strangers treated decently, the knowledge that can be gained from the company and example of Donkeyskins and cats wearing boots and steadfast tin soldiers. I���m not talking about in-your-face lessons, but more subtle ones. The kind that seep up from your sub-conscious and give you moral and humane structures for your life. That teach you how to prevail, and trust. And maybe even love."

- Charles de Lint (The Onion Girl)

''It���s no coincidence that just at this point in our insight into our mysteriousness as human beings struggling towards compassion, we are also moving into an awakened interest in the language of myth and fairy tale. The language of logical arguments, of proofs, is the language of the limited self we know and can manipulate. But the language of parable and poetry, of storytelling, moves from the imprisoned language of the provable into the freed language of what I must, for lack of another word, continue to call faith.''

- Madeleine L���Engle (A Circle of Quiet)

"It is through beauty, poetry and visionary power that the world will be renewed."

- fairy tale scholar Maria Tatar

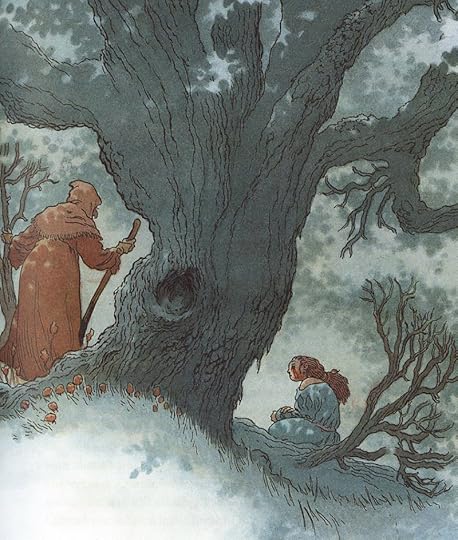

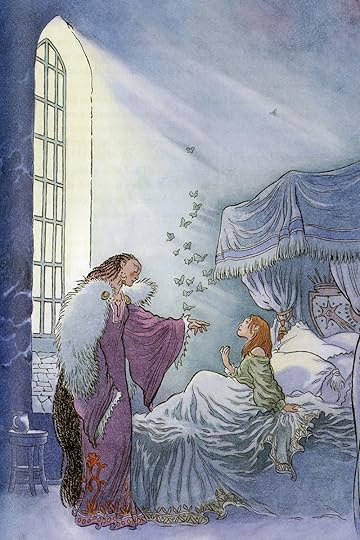

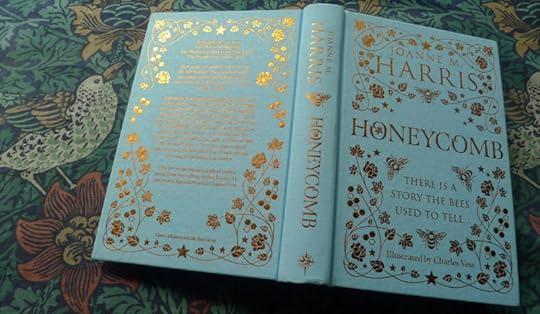

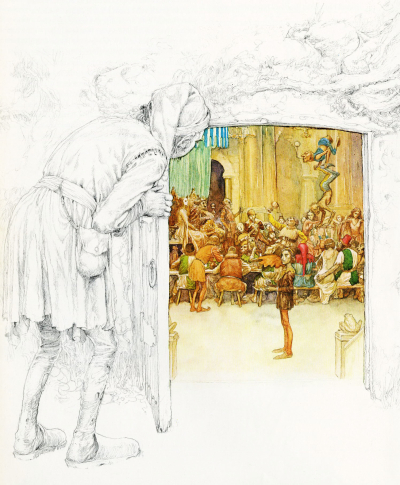

The art today is from Honeycomb, an unusual and thoroughly enchanting "mosaic novel" by Joanne Harris, with gorgeous illustrations by Charles Vess. The book, Harris explains, began like this:

"Ten years ago, I started writing little stories on Twitter. I don't know why I did this, except that Twitter seemed to me to be the right places for stories, and because I felt those stories were for telling, not writing. Some stories take life from the fact that they have an audience right there, ready to comment and react, and Twitter gave me that audience. It also gave a context to some of my stories -- which seemed at first to be fairy tales, but which were also drawn from the world of current events and politics. And as time went by, people began to request more news of their favourite characters, and I began to realize that I was creating something like a new oral tradition: a new medium for folklore. And interlinked series of stories, all set in the same honeycomb universe as The Gospel of Loki and Orfeia, with an overarching storyline about love, magic, the power of story and the request for redemption."

It's a deeply magical honeycomb of stories, an exquisitely beautiful volume, and a fascinating evolution of the fairy tale form.

The art above, by Charles Vess, consists of full illustrations and painting details for Honeycomb by Joanne Harris (Gollancz UK, 2021). The title of each piece can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights to art and text in this post reserved by the artist and authors.

June 28, 2021

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Above: "L�� Luain/The Day That Never Comes" by Rachel Walker (from Skippinish), a singer/songwriter based in the Scottish Highlands. Walker collaborated with Gaelic poet Marcas Mac An Tuairneir on the lyrics, and James Graham provides additional vocals. (Full music and animation credits can be found at the end of the video.) The song appears on her most recent solo album, Gaol (2020), which is a beauty.

Below: "T��r is S��l/Land and Sea," another songwriting collaboration between Walker and Mac An Tuairneir. It's a Gaelic waulking song, she explains, "about the ties we have to the land and the way working the land is often a love passed from generation to generation." Walker is accompanied by Aaron Jones (of Old Blind Dogs), filmed in Glasgow last autumn.

Above: "Streets of Forbes," an Australian folk song performed by Varo (Lucie Azconaga and Consuelo Nerea Breschi), a French/Italian duo based in Dublin. The song appears on their first album, Varo (2020), which displays a range of influences from Irish and world folk to medieval, baroque, and classical music. It's gorgeous.

Below: "Sovay," a traditional British folk song, also known as "The Female Highwayman." This one, too, can be found on the duo's debut album.

Above: "Three Ravens" (Child Ballad #26), performed by Hannah James & Toby Kuhn. James, an accomplished English folk musician and dancer, has performed with Lady Maisery, Maddy Prior, Songs of Separation and many others in addition to her solo work. Kuhn, a wandering cellist from Burgandy, has performed with Bipolar Bows, The Wild String Trio, Old Salt and Zamee, among others. The video above was recorded in Gent, Belgium in 2020.

Below: "The Vine Dance," with music by Toby Kuhn and traditional clog dancing by Hannah James. It is, they explain, "an original tune written in the Turkish spring under a bougainvillea and recorded in the Slovenian autumn under an apple tree" (2021).

One more, to end with....

Below: "Oblique Jig and Miss Heidi Hendy" by the Anglo/French folk-dance band Topette (Andy Cutting, James Delarre, Julien Cartonnet, Tania Buisse, and Barnaby Stradling). The song appeared on their second album, Rhododendron (2019); the video was filmed at the Sidmouth Folk Festival that same year, pre-pandemic. (A limited version of the festival is returning this summer, provided no further lockdowns occur.)

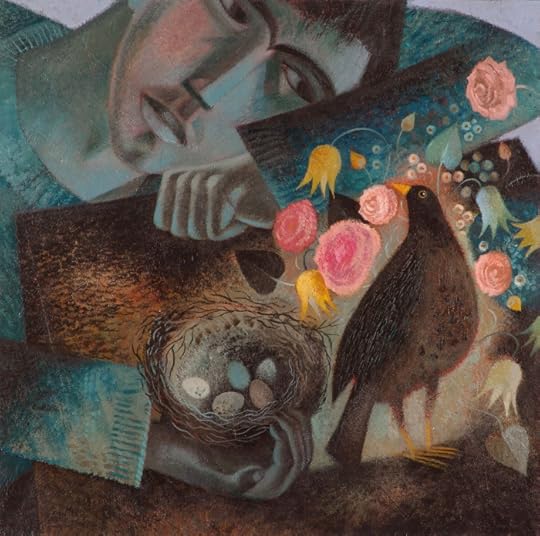

The imagery today is by two artists whose work I love beyond measure: "St Kevin and the Blackbird" by Clive Hicks-Jenkins, based in Wales; and "We Are Bird" by Rima Staines, based here on Dartmoor.

June 26, 2021

Witchery and Elizabeth Goudge

Here's another passage from The Joy of Snow, the autobiography of Elizabeth Goudge (author of The Little White Horse, Linnets & Valerians and other classics), who lived in a small village on the coast of Devon in the 1940s. It was, she says,

"an unearthly place. The round green hills where the sheep grazed, the wooded valleys and the lanes full of wildflowers, the farms and apple orchards were all full of magic, and the birds sang in that long-ago Devon as I have never heard them singing anywhere else in the world; in the spring we used to say it sounded as though the earth itself was singing.

"The villages folded in the hills still had their white witches with their ancient wisdom, and even black witches were not unknown. I have never had dealings with a witch either black or white, though Francis, our village chimney-sweep, a most gentle and courteous man, was I think half-way to being a white warlock. He was skillful at protecting his pigs from being overlooked. He placed pails of water on the kitchen floor to drown the Evil Eye and nothing ever went wrong with his pigs before their inevitable and intended end.

"Black magic is a thing to vile to speak of, but many of the white witches and warlocks were wonderful people, dedicated to their work of healing. I knew the daughter of a Dartmoor white witch and she told how her mother never failed to answer a call for help. Fortified by prayer and a dram of whiskey she would go out on the coldest winter night, carrying her lantern, and tramp for miles across the moor to bring help to someone ill at a lonely farm. And she brought real help. She must have had the true charismatic gift, and perhaps too knowledge of the healing herbs.

"The father of one of my friends had a white witch in his parish in the valley of the Dart. She was growing old and she came to him one evening and asked if she might teach him her spells before she died. They must always, she said, be handed on secretly from woman to man, or from man to woman, never to a member of the witch's or warlock's own sex. 'And you, sir,' she told him, 'are the best man I know. It is to you I want to give my knowledge.'

"Patiently he tried to explain why it is best that an Anglican priest should not also be a warlock, but it was hard for her to understand. 'But they are good spells,' she kept telling him. 'I know they are,' he said, 'but I cannot use them.' She was convinced at last but she went away weeping."

In her lovely essay "Elizabeth Goudge: Glimpsing the Liminal," Kari Sperring notes:

"The most overtly magical of Goudge���s adult books is probably The White Witch, which is set against the early years of the English Civil War. The protagonist Froniga is, as the title suggests, a working witch, the daughter of a settled father and a Romani mother, and she possesses both the power to heal and the power to see the future. Yet while both are important to the plot, the book is not about her powers, but about her selfhood and character and her effect on those around her. A lesser writer would probably have taken this theme in the direction of witch trials and melodrama. Goudge uses it to examine the effects of divided politics on families and communities and the ways in which our beliefs affect others outside ourselves.

"Her characters do bad things, sometimes, and those have consequences, but she rarely writes bad people -- I can think of only one, the greedy and self-obsessed school-owner Mrs. Belling in The Rosemary Tree. Goudge was concerned not with judging others but with understanding them with compassion. In her case, that compassion is linked to her sense of otherness -- the most profound experiences of liminality her characters experience are often when they are most concerned with others than themselves."

The passage by Elizabeth Goudge is from The Joy of Snow: An Autobiography (Hodder & Stoughton, 1974). The passage by Kari Sperring is from "Elizabeth Goudge: Glimpsing the Liminal" (Strange Horizons, February 22, 2016). The poem in the picture captions is from Poems of Denise Levertov: 1960-1967 (New Directions, 1983). All rights reserved by the authors or their estates.

June 25, 2021

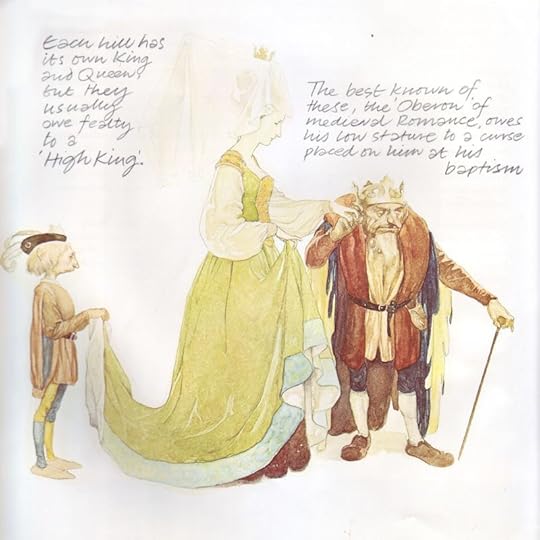

Fairies and Elizabeth Goudge

From The Joy of Snow, an autobiography by Elizabeth Goudge (author of The Little White Horse, Linnets & Valerians and other classics), who lived in Marldon near Dartmoor in the 1940s:

"I think that in my heart I have always believed in fairies,not fairies as seen in the picture books but nature spirits whose life is part of the wind and the flowers and the trees. Born in the West Country, and returning to it in middle life, how could I do anything else? But alas, I have never seen them.

"William Blake saw fairies, but he was a unique person, and so was a Dartmoor friend of mine who used to see them, and how I envied her! But if I did not see them I could feel how magic ran in the earth and branched in one's veins when one sat down. The stories that some of my Dartmoor friends told me would be laughed at by most people, but they were sensible persons and they did not laugh. I think that probably the one among my friends who experienced most was the one who said the least about it, Adelaide Phillpotts, Eden Phillpotts' daughter. She lived for years upon the moor and she loved it so deeply that she was not afraid to spend whole nights alone on the tors; but she is a mystic and mystics seem always unafraid. Her book The Lodestar is full of the wild spirit of the moor.

"The friend who saw fairies, when she first went to live in her cottage on the moor, was visited early in the morning by a little old woman, wearing a bonnet, who walked quietly into the kitchen where she was preparing breakfast. Friendly and smiling the old woman refused breakfast but sat down to chat. She wanted to know exactly what my friend intended to do in the garden. What flowers would she have? What vegetables? She had very bright eyes and nodded her head in approval as they talked. She seemed a happy old woman, very much at home in the kitchen, but when my friend turned away for a moment she found on looking around again that her visitor had left her. She was never seen again and when the neighbors were questioned they denied ever having seen such an old woman in the village.

"Another friend was driving back to her home on the moor one summer evening when she found herself in the most beautiful wood. She had no sense of strangeness but drove through it entranced by the loveliness of the evening light shining through the trees. Coming out of the wood she found herself at home, put the car away and went about the normal business of the evening, and only gradually did she remember that her road home lay through an open stretch of moorland. There was no wood there; not now.

"The next day she went to see an old man who had lived all his life on the moor and told him what had happened. He nodded his head.

"'I know the wood, ma'am,' he told her. 'I've been there myself. But only once. You'll not see it again. It's only once in a lifetime.' "

Although Goudge never saw fairies herself, she did have a mystical experience in Devon:

"My mother and I had a cottage in an apple orchard at the edge of a village," she explains, "and behind the cottage, between the orchard and the village, there was a steep hill. To the right, Dartmoor was visible, but otherwise the place was a little valley in the hills that had a magic of its own. There were a few other small dwellings besides our own, an old house behind a high wall, a farm and some cottages, and so strictly speaking the place was not a lonely one, and yet, because of its particular magic, it was. Especially in the early morning and especially after a snow-fall. There is something very lonely about a deep snow-fall and Devon snow, because the average rainfall is high, is almost always deep. One is walled in and cut off. The world seems very far away and the heart rejoices.

"In spring, in Devon, there is often a sudden late snow-fall taking one entirely by surprise. I remember once seeing irises and tulips with their bright heads lifted above a deep counterpane of snow, and boughs of apple blossoms sprinkled with sparkling silver. But the snowfall [on this occasion] was earlier in the year. There were only the low-growing flowers in bloom in the garden and they were all buried out of sight. There had been no wind in the night, no suggestion that the last snow of the year was falling, and when I drew the curtains early in the morning I was astonished to see the white world. And what a world! I had never seen a snow-fall so beautiful and I was out in the garden at the first possible moment. The snowclouds had dropped their whole treasure in the night and were gone. The huge empty sky was deep blue, the air sparkling and clear. The sun was rising and the tree shadows lay blue across the sparkling whiteness. The whole world was pure blue and white and it seemed that the sun had lit every crystal to a point of fire. There was a silence so absolute it seemed a living presence. And then came the singing.

"It was a solo voice, ringing out joy and praise. One would have said it was a woman's voice, only could any woman sing like that, with such simplicity and beauty? It lasted for some minutes, and then ceased, and the deep silence came back once more.

"I stayed where I was, as rooted in the snow as the trees, but there was no return of the singing and so I went back to the cottage and mechanically began the first task of the day, raking out the ashes of the dead fire and lighting a new one. The light of the flames helped me to think. None of us, in the little group of dwellings in the valley had a voice much above a sparrow's chirp. No one in the village that I knew had a voice like that. It was war-time and visitors from the outside world seldom came. Even if by some extraordinary chance some great singer had descended upon us, what would she be doing struggling down the steep lane from the village in deep snow at this hour of a cold morning? And wouldn't I have seen her? I could see both lanes from the little terrace outside the cottage and had seen no one. There were only two explanations. Either I was mad or I had heard a seraph singing. Later when I took my mother her breakfast I told her of the singing. She looked at me and, as usual, made no comment whatsoever.

"And so, for some years, I inclined to the former view and told no one else about the singing. And then, one day after the war had ended, a very sensitive and sympathetic cousin came to visit us and told me about a holiday he had had in the wilds of Argyll. He had always wanted, he said, to talk to someone who had heard the singing and at last he come upon an old crofter who could tell him about it. The old man had been alone in the hills when he heard a clear voice, unearthly and very beautiful, singing in the silence. He could see no one, he could distinguish no words in the singing and the song was one he did not know. He tried to hum the air and my cousin tried to write it down, but they neither of them made much of a job of it. 'You never heard it again?' my cousin asked and the old man said, like the old countryman who was in the wood only once, 'No, never again.'

"My cousin told this tale so beautifully that I was too awed and shy to tell him, then, about my own experience. Besides, the great paean of praise I had heard in the snow seemed at that moment a little theatrical in comparison with the soft unearthly singing in the hills of Argyll. But, some years later, I did tell him. He was very kind, and he did not doubt my sincerity, but somehow I seemed to see at the back of his mind the figure of a stout opera singer from Covent Garden who had somehow, even in war-time and deep snow, got herself hidden behind the fir trees at the corner of our Devon garden.

'It does not matter. I remember that singing every morning of my life and I greet every sunrise with the memory. The birds, who had been singing so riotously, had been chilled to silence by that snowstorm. I have decided now that she, whoever she was, sang their dawn-song for them."

Words: The passage by Elizabeth Goudge is from The Joy of Snow: An Autobiography (Hodder & Stoughton, 1974). The poem in the picture captions is from Marrow of Flame by Dorothy Walters (Poetry Chaikhana, 2015). All rights reserved by the authors.

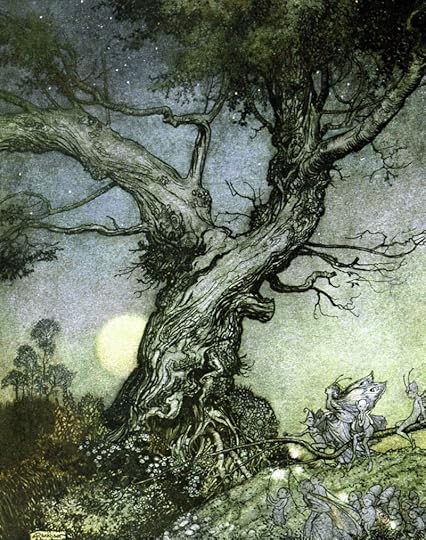

Pictures: "King & Queen of the Faery Hill" by Alan Lee and"Cowslip Faery" by Brian Froud are from their book Faeries (Abrams, 1978); all rights reserved. The last three fairy pictures are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). The Dartmoor photographs were taken by the Scorhill stone circle, near Gidleigh. The beautiful quilt in the last photo was made by Karen Meisner.

A related post: Visiting Moonacre Manor (from The Little White Horse).

June 24, 2021

The stolen child

It's International Fairy Day, and so today's post is on fairy changelings....

"Come away, O human child!" call the fairies in a poem by William Butler Yeats inspired by Irish folktales of children abducted to fairyland. Yeats was a folklore enthusiast and a life-long believer in the fairy folk. His poem "The Stolen Child" is rooted in changeling tales found throughout the British Isles, as well as in other lands with fairy traditions of their own. Changeling stories are not "fairy tales" as the term is commonly used today. They are not set "once upon a time" in magical lands distant from our own, like fairy tales such as Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, or Puss in Boots. Changeling stories are folk legends, usually set in the same country as the teller, and come from an ancient belief system in which fairies are real, co-existing with mortals.

A typical changeling story is the following tale from the mountains of northern Wales: A farmer and his wife lived in a cottage with their infant son. One day, while the farmer was in the field, the wife was called away from home to tend to the health of an old woman who lived just down the road. The child was sleeping peacefully, so the farmwife left the babe in the cradle while she visited her neighbor, turning homeward again at dusk. As she

A typical changeling story is the following tale from the mountains of northern Wales: A farmer and his wife lived in a cottage with their infant son. One day, while the farmer was in the field, the wife was called away from home to tend to the health of an old woman who lived just down the road. The child was sleeping peacefully, so the farmwife left the babe in the cradle while she visited her neighbor, turning homeward again at dusk. As she

traveled back, her path was crossed by the Twyleth Teg (the fairies of Wales), so she rushed to her house and was greatly relieved to find the cradle undisturbed. She quickly scattered salt on the doorstep and on each of the windowsills to protect the child from fairy mischief, as she should have done before.

Alas, she was too late. The boy had been a fat and jolly child, but now he grew pale and wan and howled in his cradle for hours on end.

"This creature is not ours," said the farmer.

"Whose then should he be?" said the wife.

"He belongs to the Twyleth Teg," said the man. "We must put him out on the cold hillside and see if the fairies come to reclaim him." But his wife would not allow any harm to come to the child she thought was her own.

The troubled woman continued to feed and dress and clean the babe, though his face now looked like a wizened old man's and his milk teeth grew into points. The infant's appetite grew and grew while his chest and his stick-like limbs seemed to shrink. When the baby had eaten through all of their stores, and still he continued to howl for more, the farmwife left the cottage to seek her old neighbor's advice.

"Go home," the old woman replied, "and do what I shall tell you to do. Then you will know if this is your son, or one of the Twyleth Teg."

Following the old woman's instructions, the farmwife procured a large hen's egg, returned to the cottage, and broke the egg in front of the child's cradle. She cleaned the shell and filled it with porridge, then set it to boil on the fire. The infant watched her closely with a frown on his wizened face. Finally, he could contain his curiosity no longer. "What are you doing?" the boy piped up.

Following the old woman's instructions, the farmwife procured a large hen's egg, returned to the cottage, and broke the egg in front of the child's cradle. She cleaned the shell and filled it with porridge, then set it to boil on the fire. The infant watched her closely with a frown on his wizened face. Finally, he could contain his curiosity no longer. "What are you doing?" the boy piped up.

The woman was startled to hear him speak but answered as she'd been instructed. "Why, I'm making dinner for the men in the fields. They'll be hungry after all of their work."

The infant laughed and said: "Acorn before oak I knew, and an egg before a hen, but never before have I seen an eggshell brew dinner for harvest men."

With these words, the creature betrayed his great age and the farmwife knew that her husband was right. This was not their own dear boy but a fairy who'd taken his place. She picked up the shovel and put more coals on the fire until it roared with heat.

"What are you doing now?" asked the infant.

"Preparing to throw you on the fire." As she spoke these words, she snatched him up and threw the creature onto the flames, where he changed to a puff of smoke and left the house through the chimney. And in his place sat her own fine son, returned by the Twyleth Teg.

There are numerous variants of this curious story. In some versions the threat of violence alone is enough to betray the fairy's true nature, while in others it's beer that the farmwife brews in a shell, to the fairy's surprise. In a changeling tale from the Isle of Man, a visiting tailor discovers the fairy's deception. When his hosts leave the house to work in the fields, leaving the tailor alone with the child, the infant leaps up from the cradle, demanding whisky and a fiddle tune. In most stories, the human child is restored safe and sound once the changeling has fled, though there are bleaker versions in which the only resolution of the tale is the banishment of the troublesome fairy, while the real child remains lost forever. In some of the tales, however, further action is needed to save the child, kept in captivity or slavery in a fairy hill.

In a tale from the West Highlands of Scotland, for instance, the son of a smith is stolen away and an evil���tempered changeling called a Sibhreach is left in his place. The Sibhreach is exposed and banished, but still the mortal child remains missing, and the smith must go in search of him beneath a fairy hill. He waits for a night when the hill will be open, then follows the sound of fairy music. Armed with a Bible, a knife, and a cock, he walks boldly into the fairy court. The Bible protects him from their mischief, the knife holds open the door of the hill, and the crowing cock annoys the fairies so much that they toss the smith and his son back into the mortal world.

In a tale from the West Highlands of Scotland, for instance, the son of a smith is stolen away and an evil���tempered changeling called a Sibhreach is left in his place. The Sibhreach is exposed and banished, but still the mortal child remains missing, and the smith must go in search of him beneath a fairy hill. He waits for a night when the hill will be open, then follows the sound of fairy music. Armed with a Bible, a knife, and a cock, he walks boldly into the fairy court. The Bible protects him from their mischief, the knife holds open the door of the hill, and the crowing cock annoys the fairies so much that they toss the smith and his son back into the mortal world.

There are various reasons given for the fairies' penchant for stealing human children. Some tales imply that the young mortals are destined for lives as servants or slaves, or are kept (in the manner of pets) for the amusement of their fairy masters. Some stories (in echo of the folk ballad Tam Lin) suggest a darker purpose: that the faeries must pay a tithe of blood to the devil every seven years, and prefer to pay with mortal blood rather than blood of their own. In some traditions, however, it's simply the beauty of the children that attracts the fairies, who also kidnap pretty young women, artists, and musicians. The ability of fairies to procreate is a debatable issue in fairy lore. Some stories maintain that the fairies do procreate, though not as often as humans. By occasionally interbreeding with mortals and claiming mortal babes as their own, they bring new blood into Fairyland and keep their bloodlines strong. Other tales suggest that they cannot breed, or do so with such rarity that jealousy of human fertility is the motive behind child-theft.

Some stolen children, the tales tell us, will spend their whole lives in Fairyland -- and may even find happiness there, losing all desire for the lands of men. Other tales tell us that human children cannot thrive beneath the hills, and eventually sicken and die for want of mortal food and drink. Some fairies maintain their interest in child captives only during their infancy, tossing the children out of the fairy realm when they show signs of age. Such children, restored to the human world, are not always happy among their own kind, and spend their mortal lives pining for a way to return to Faerie.

One of the interesting aspects of changeling tales is that each contains the seeds of two separate stories: of the human child in fairyland, and of the changeling in the mortal world. The changeling "child" isn't usually a child at all, but merely takes on that appearance. Sometimes changelings are old, nasty fairies who revel in the sorrow they cause; or fairies with prodigious appetites for human food or mortal breast milk. Sometimes the changelings are fairies so old and worn out that their kinfolk have left them behind, happy to be rid of them in exchange for a plump human child. In these cases, the changeling withers and dies while the human parents look on, grieving for the loss of a baby they think is their own son. Yet we do find some interesting stories in which the fairy changeling is also a child. One tale from England's West Country tells of a farmer's youngest son who is stolen and replaced by a sickly, sallow, silent imp of a boy. The farmer and his wife raise the queer little child as tenderly as their own. Some years later, a piskie appears at their door. "Father!" the boy cries out. The pair runs off, and the farm is blessed with good fortune from that day forward (though no mention is made, at the end of the tale, of the fate of the farmer's true son.) Sometimes the changeling is not even a fairy -- merely a stock of wood, or a block of wax, enchanted to look like a child. When the trick is discovered, the "infant" must be thrown onto the hearth fire. Wood burns, or wax melts away, and then the true child is restored.

One of the interesting aspects of changeling tales is that each contains the seeds of two separate stories: of the human child in fairyland, and of the changeling in the mortal world. The changeling "child" isn't usually a child at all, but merely takes on that appearance. Sometimes changelings are old, nasty fairies who revel in the sorrow they cause; or fairies with prodigious appetites for human food or mortal breast milk. Sometimes the changelings are fairies so old and worn out that their kinfolk have left them behind, happy to be rid of them in exchange for a plump human child. In these cases, the changeling withers and dies while the human parents look on, grieving for the loss of a baby they think is their own son. Yet we do find some interesting stories in which the fairy changeling is also a child. One tale from England's West Country tells of a farmer's youngest son who is stolen and replaced by a sickly, sallow, silent imp of a boy. The farmer and his wife raise the queer little child as tenderly as their own. Some years later, a piskie appears at their door. "Father!" the boy cries out. The pair runs off, and the farm is blessed with good fortune from that day forward (though no mention is made, at the end of the tale, of the fate of the farmer's true son.) Sometimes the changeling is not even a fairy -- merely a stock of wood, or a block of wax, enchanted to look like a child. When the trick is discovered, the "infant" must be thrown onto the hearth fire. Wood burns, or wax melts away, and then the true child is restored.

In Germany, the Brothers Grimm collected a number of interesting changeling tales, such as the story of the Rye-Mother (or Grain-Wife), published in German Legends. A nobleman had forced one of his peasants to work binding sheaves during the harvest, even though the poor woman had given birth but a few weeks before. She took the child to the field, laid it down, and got on with her work, despite her fears for the child because it had not yet been properly baptized. Some time later, the nobleman himself saw a Rye-Mother cross the field. She carried a child in her arms, which she  exchanged for the peasant's baby. The false child began to cry, and the peasant hurried over to nurse it -- but the nobleman held her back. He made her wait while the child cried and wailed -- until at last the Rye-Mother returned, exchanged the children again, and left with her own child, who now quieted in his mother's arms. "After seeing all of this transpire," the Grimms write, "the nobleman summoned the peasant woman and told her to return home. And from that time forth he resolved to never again force a woman who had recently given birth to work."

exchanged for the peasant's baby. The false child began to cry, and the peasant hurried over to nurse it -- but the nobleman held her back. He made her wait while the child cried and wailed -- until at last the Rye-Mother returned, exchanged the children again, and left with her own child, who now quieted in his mother's arms. "After seeing all of this transpire," the Grimms write, "the nobleman summoned the peasant woman and told her to return home. And from that time forth he resolved to never again force a woman who had recently given birth to work."

In other German stories, mortal children are stolen and held captive by bands of elves, who leave greedy changelings called killcrops behind in the cradle, wailing for food. The killcrop is revealed through the brewing of beer in an eggshell, or some other trick, then threatened with violence to make it flee, restoring the mortal child. Nickerts were German water fairies fond of stealing children from unwary parents, then taking their place in the cradle in order to eat mortal food and milk. Nixies also inhabited German rivers, and could be dangerous. "From time to time nixies would emerge from the Saal River," wrote the Brothers Grimm, "and go into the city of Saalfeld where they would buy fish at the market. They could be recognized by their large, dreadful eyes and by the hems of their skirts that were always dripping wet. It is said that they were mortals who, as children, had been taken away by nixies, who had then left changelings in their place."

In Scandinavia, healthy mortal infants had to be guarded from covetous trolls, who found them more beautiful and appealing than their own peevish, hairy troll children. One farmwife, suspecting her own sweet-natured child had been stolen by the trolls, was determined to rid herself of the troublesome creature who had taken his place. She set a cauldron in the hearth, took hold of the porridge spoon and bound a number of rods to it till the spoon reached up to the ceiling. "Well!" the child blurted out. "I am old as the trees and old as the hills, but never in my life have I seen such a long, long spoon for such a small, small pot!" Confirmed in her suspicions, the farmwife beat the changeling with her broom. As he howled and wailed, a trollwife entered the cottage bearing the farmwife's son and said, "See how we differ! I've cherished your son, while you beat my husband black and blue!" She then took the changeling by the hand and disappeared up the chimney.

Similar tales can be found the world over. In India, tigers steal mortal children and leave behind tiger cubs in disguise. When the trick is uncovered and the cubs threatened with harm, the tiger reappears, restores the mortal child, and leaves again with his wild brood. In Japan, children stolen by the fairies are rarely restored to the human world unless the substitution can be discovered before the child eats fairy food. In an odd twist on the theme, in old Persian tales it is the fairies (called peries) whose children are stolen -- by evil creatures called djinn, who substitute their own children instead.

We also find stories in various cultures in which such substitution, rather than abduction, is the goal. In these tales, mortals are the unwitting foster parents for faery children; such children are generally odd, dreamy, and incapable of human emotion. Eventually these parents learn that the changeling child is not, in fact, of their blood. The changeling is called back to Fairyland, and the human child is restored.

We also find stories in various cultures in which such substitution, rather than abduction, is the goal. In these tales, mortals are the unwitting foster parents for faery children; such children are generally odd, dreamy, and incapable of human emotion. Eventually these parents learn that the changeling child is not, in fact, of their blood. The changeling is called back to Fairyland, and the human child is restored.

A number of preventive measures are recommended to insure against fairy abduction. Writing in Notes of the Folklore of the Northern Counties of England and the Border, William Henderson tells us: "In the southern counties of Scotland children are considered before baptism at the mercy of the fairies, who may carry them off at pleasure or inflict injury upon them. Hence, of course, it is unlucky to take unbaptized children on a journey...Danish women guard their children during this period against evil spirits by placing in the cradle, or over the door, garlic, salt, bread, and steel in the form of some sharp instrument...In Germany, the proper things to lay in the cradle are 'orant' (which is translated into either horehound or snapdragon), blue marjoram, black cumin, a right shirtsleeve, and a left stocking.  The 'Nickert' cannot then harm the child. The modern Greeks dread witchcraft at this period of their children's lives, and are careful not to leave them alone during their first eight days, within which period the Greek Church refuses to baptize them."

The 'Nickert' cannot then harm the child. The modern Greeks dread witchcraft at this period of their children's lives, and are careful not to leave them alone during their first eight days, within which period the Greek Church refuses to baptize them."

Other charms include wreaths made of ivy and oak, which hindered fairy access to a house; also salt on the doorstep, or branches of rowan, or the father's shirt draped over the cradle.

Most of the children kidnapped were boys, so another method of thwarting the fairies was to dress little boys in girls' clothing and then to call them by female names. Newborn babies, it was advised, must be zealously guarded their first three days, and then closely watched until their baptism, when the threat of abduction lessened. Yet even older children could be stolen or tempted into Fairyland. Just as today young children are warned that they must never take candy from strangers, generations ago they were warned to beware of faeries that lurked in the countryside, seductive creatures who would whisk them away, never to be seen again.

When we hear fairy tales, we're hearing a story we believe in just for the length of the tale -- stories of impossible things, enchanted princesses and cats in boots. Fairy legends, however, were cautionary tales meant to illustrate the particular dangers of encounters with creatures that many people once believed in.

The 16th century preacher Martin Luther recounts this tale of a changeling in Germany: "Eight years ago at Dessau, I, Dr. Martin Luther, saw and touched a changeling. It was twelve years old, and from its eyes and the fact that it had all of its senses, one could have thought that it was a real child. It did nothing but eat; in fact, it ate enough for any four peasants or threshers. It ate, shit, and pissed, and whenever someone touched it, it cried. When bad things happened in the house, it laughed and was happy; but when things went well, it cried. It had these two virtues. I said to the Princes of Anhalt: 'If I were the prince or the ruler here, I would throw this child into the water -- into the Molda that flows by Dessau. I would dare commit homicidium on him!' But the Elector of Saxony, who was with me at Dessau, and the Princes of Anhalt did not want to follow my advice. Therefore, I said: 'Then you should have all Christians repeat the Lord's Prayer in church that God may exorcise the devil.' They did this daily at Dessau, and the changeling child died in the following year....Such a changeling child is only a piece of flesh, a massa carnis, because it has no soul."

The 16th century preacher Martin Luther recounts this tale of a changeling in Germany: "Eight years ago at Dessau, I, Dr. Martin Luther, saw and touched a changeling. It was twelve years old, and from its eyes and the fact that it had all of its senses, one could have thought that it was a real child. It did nothing but eat; in fact, it ate enough for any four peasants or threshers. It ate, shit, and pissed, and whenever someone touched it, it cried. When bad things happened in the house, it laughed and was happy; but when things went well, it cried. It had these two virtues. I said to the Princes of Anhalt: 'If I were the prince or the ruler here, I would throw this child into the water -- into the Molda that flows by Dessau. I would dare commit homicidium on him!' But the Elector of Saxony, who was with me at Dessau, and the Princes of Anhalt did not want to follow my advice. Therefore, I said: 'Then you should have all Christians repeat the Lord's Prayer in church that God may exorcise the devil.' They did this daily at Dessau, and the changeling child died in the following year....Such a changeling child is only a piece of flesh, a massa carnis, because it has no soul."

Changeling stories are both fascinating and horrifying when we realize how such tales once accounted for the mysteries of wasting diseases, physical or mental disabilities, even differences of neurodivergence. Children suffering illnesses such as cystic fibrosis, cerebral palsy and spina bifida, or simply born with conditions such as Downs syndrome, were explained away as fairy changelings, sometimes with deeply tragic results. As late as the 19th century in Britain, changeling stories in the press told of children subjected to violent "cures" intended to make the fairy flee and bring back the "real" child. Sir William Wilde (medical commissioner for the Irish census, and father of Oscar Wilde), writing in 1854, decried "the cruel endeavors to cure children and young persons of such maladies generally attempted by quacks and those termed 'fairy men' and 'fairy women'."

The most famous case of "fairy doctoring" involved a grown woman in 1895, and riveted newspaper readers all across the British Isles. This was the murder of Bridget Cleary, a handsome young Irish woman who was killed by her husband, family, and neighbors because they thought she was a fairy changeling. The facts are these: Bridget, a twenty-six-year-old dressmaker, and her husband Michael, a cooper, lived in a comfortable cottage near her family home in southern Ireland. Bridget fell sick with an undiagnosed illness (it may have been simple pneumonia); within a few days she was feverish, raving, and (according to her husband) no longer looked like herself. When regular medicine did not help, the family called in a "fairy doctor" -- for the cottage was located close to a fairy hill, which was bad luck. The fairy doctor confirmed that the ill woman was actually a fairy changeling and the real Bridget had been abducted, taken under the hill by the fairies as a consort or a slave. The doctor devised several ordeals designed to make the changeling reveal itself. Bridget was tied to the bed, forced to swallow potions, sprinkled with holy water and urine, swung over the hearth fire, and eventually burned to death by her increasingly desperate husband. Convinced it was a fairy he had killed and buried (with the aid of her family and neighbors), Michael then went to the fairy fort to wait for the "real" Bridget to ride out seated on a milk white horse. Bridget's disappearance was soon noted, the body found, the crime brought to life, and Michael and nine others were charged and prosecuted for murder.

Although the most flamboyant, this was far from the only case of changeling-murder in the Victorian press, although the poor changeling were more commonly children with physical or mental ailments, or those perceived to be wayward or different from the norm.

Victorian interest in changeling stories extended to works of literature, as we see in many publication of the period with changeling themes. Children were abducted by goblins in George MacDonald's children's novel The Princess and the Goblin, for example, and the heroine of Amelia and the Dwarfs by Juliana Horatio Ewing was kidnapped by a pack of nasty dwarfs and replaced by a wooden stock. In Rudyard Kipling's Rewards and Fairies, Puck denies the fairies' reputation for stealing human children. ("All that talk of changelings is people's excuse for their own neglect," he says.) In Fiona MacLeod's affecting story "The Fara Ghael," a Scottish woman exposes her sickly changeling child on a lonely beach, and is given a beautiful girl in its place that she raises, thinking it is her own. Eventually she learns that wild, beautiful girl is the real changeling, and her own daughter was the unloved creature she'd left out by the tide. Other Victorian/Edwardian stolen-child stories include Walter Besant's The Changeling, Selma Lagerl��f's The Changeling, Dinah Muroch Craik's Olive, Arthur Machen's The Shining Pyramid, Sheridan LeFanu's "The Child That Went With the Fairies," and John Buchan's "The Watcher by the Threshold."

Changeling/stolen-child stories are closely related to "wild child" tales -- about lost children, runaway children and feral children in the wilderness -- the most famous of them being Mowgli's adventures in The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling. All of these themes come together in J.M Barrie's tales of Peter Pan, in which the lost or wild child, Peter, becomes a kind of fairy himself (identified with Puck, and Pan -- god of the wilderness), stealing away the children in the Darlings' nursery in London. The original text of Barrie's Peter and Wendy is far more interesting than the surgery Disney-flavor adaptations most people know today, for Barrie's humor is arch, dark, and sometimes downright sinister.

Whether the child is abandoned to the wilderness or runs away to it purposefully, the focus of "wild child" stories is very different than that of changeling tales. Here the children, Here, the children live in a world beyond adult rules, a world of continual play and adventure, befriended by animals, fairies, outlaws, and other denizens of the forest. As parents, the thought of lost children is disturbing...but when we read such tales from a child's point of view, the idea of shedding the strictures of civilization and heading off into the wild is thrilling.

"Come away, O human child!" call the fairies.

Come away from all human sorrow, they promise. Come into the wild, come under the hill, where life is an endless round of feasting, dancing, adventure and enchantment. But fairy promises can deceive, and following the elfin call (folklore reminds us) is a very dangerous proposition. We do not thrive in that Otherworld where the sun doesn't shine and the Folk never change and little boys and girls never grow up. We are mortal creatures, we belong to the lands of time and change, of sorrow and joy.

Close the door now, child. Lock the windows tight. Don't listen.

"Come away..."

Don't listen.

Some further reading:

20th & 21st novels inspired by changeling tales include The Broken Sword by Poul Andersen, Tithe by Holly Black, The Truth About Celia by Kevin Brockmeier, The Stolen Child by Keith Donohue, The Managerie by Christopher Golden and Thomas E. Sniegoski, The Lastborn of Elvinwood by Linda Haldeman, Cuckoo Song by Frances Hardinge, The Moorchild by Eloise McGraw, The Book of Atrix Wolfe by Patricia A. McKillip, Harvest of Changelings by Warren Rochelle, The Book of the Fey Series by Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Changeling by Delia Sherman, The Changeling by Zilpha Keatley Snyder, The Changeling by me (a very short book for 8-to-12 year olds), and Changeling by Roger Zelazny. Some short stories: "The Changeling" by A.S. Byatt (from Sugar and Other Stories), "The Green Children" by John Crowley (from Elsewhere, Volume I), "Lullaby for a Changeling" by Nicholas Stuart Gray (from The Edge of Evening), "Debt in Kind" by Peg Kerr (from Weird Tales magazine, Fall 1990), "Catnyp" by Delia Sherman (from The Faery Reel), "Brat" by Theodore Sturgeon (from The Perfect Host), and "The Green Children" by me (from The Armless Maiden). There's also a gorgeous "Green Children" poem by Jane Yolen, and Sylvia Townsend Warner's brilliant collection of fairy stories of adults, The Kingdoms of Elfin. If I've missed any good books or stories, please add to this list in the Comments.

For more information about changelings, try: The Burning of Bridget Cleary by Angela Bourke, The Cooper���s Wife is Missing: The Trials of Bridget Cleary by Joan Hoff and Marian Yeates, At the Bottom of the Garden: A Dark History of Hobgoblins, Nymphs, and Other Troublesome Things by Diane Purkiss, Strange and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Consciousness by Carole G. Silver, and the various fairy studies and guides by folklorist Katherine Briggs, Thomas Keightly, and W.Y. Evans-Wentz.

For more of my own writing about fairies/faeries, see my long essay on the subject: Fairies in Legend, Lore, and Literature. Fairies also appear in Tales of a Half-Tamed Land: Devon Folklore, Troll Maidens & the Magic of Bridges, and The Wild Hunt. Here's a page of links to fairy books I've worked on over the years, with Brian & Wendy Froud and others; and two pages of posts about the Modern Fairies project (scroll down to the beginning to read them in order).

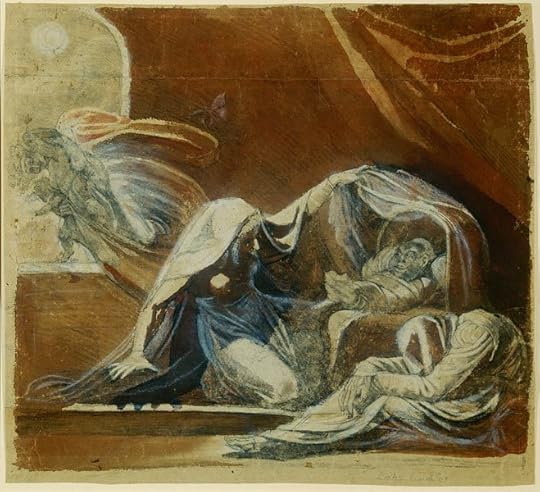

The art above is by Arthur Rackham, P.J. Lynch, Alan Lee, Brian Froud, Julia Jeffreys, John Bauer, Henry Fuseli, John Anster Fitzgerald, Maurice Sendak, Danielle Barlow, Charles Altamont Doyle, and Eleanor Vere Doyle. Each picture is individually credited in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights are reserved by the artists.

June 23, 2021

Remembering who we are

From Beauty: The Invisible Embrace by the late Irish poet and philosopher John O'Donohue, whose books I return to again and again:

"The earth is our origin and destination. The ancient rhythms of the earth have insinuated themselves into the rhythms of the human heart. The earth is not outside us; it is within: the clay from where the tree of the body grows. When we emerge from our offices, rooms and houses, we enter our natural element. We are children of the earth: people to whom the outdoors is home. Nothing can separate us from the vigour and vibrancy of this inheritance. In contrast to our frenetic, saturated lives, the earth offers a calming stillness. Movement and growth in nature takes time. The patience of nature enjoys the ease of trust and hope. There is something in our clay nature that needs to continually experience this ancient, outer ease of the world. It helps us remember who we are and why we are here."

"Our times are driven by the inestimable energies of the mechanical mind; its achievements derive from its singular focus, linear direction and force. When it dominates, the habit of gentleness dies out. We become blind: nature is rifled, politics eschews vision and becomes the obsessive servant of economics, and religion opts for the mathematics of system and forgets its mystical flame."

"Yet constant struggle leaves us tired and empty. Our struggle for reform needs to be tempered and balanced with a capacity for celebration. When we lose sight of beauty our struggle becomes tired and functional. When we expect and engage the Beautiful, a new fluency is set free within us and between us. The heart becomes rekindled and our lives brighten with unexpected courage."

Words: The passages above are from Beauty by John O'Donohue (HarperCollins, 2004). All rights reserved by the author's estate. Pictures: Reading and writing by the leat on a bright summer's day.

June 22, 2021

Finding the words

While passing through a period of low health these past weeks, I was reminded of the following passage from "Writing With and Through Pain" by Sonya Huber, which I send out to all who balance art-making with managing an illness or disability. Huber writes:

"It���s an odd thing to continue to show up at the page when the brain and the fingers you bring to the keyboard have changed. Before the daily pain and head-fog of rheumatoid disease, I could sit at my computer and dive headlong into text for hours. Like many writers, I had a quasi-religious attachment to the feeling of jet-fuel production, the clear writing process of my twenties: the silence I required, the brand of pen I chose when I wrote long-hand, those hours when I would sit and pour out words and forget to breathe.

"Then, I thought that my steel-trap focus made for good writing, but I confess that I���m not sure what 'good writing' means anymore. For example, what happens when the fogged writing you thought was sub-par results in your most popular book? ...

"Today I am tired -- despite a full night���s sleep -- merely because I had a busy workday yesterday. I���m actually hungover, in a sense, from standing upright and talking between 9:00 am and 5:00 pm. Before I got sick, I would have declared this day a rare lost cause. But this is the new normal. Now, even the magic of caffeine doesn���t allow me to smash through the pages like I used to. As my body and mind changed, I feared that I would become unhinged from text itself, and from the thinking and insight that text provides. In a way, that did happen. Over the past decade, I have had to remake my contract with sentences and with every step of the writing process. The good thing is that there���s plasticity in that relationship, as long as I am patient.

"I don���t know a lot about neurology, but here���s what it feels like: there���s a higher register, buzzing, logical, and mathematical, in which I could often write when I was at full energy. And then there���s a lower tone, slower and quieter -- my existence these days. The music of the words sounds completely different at this lower register, producing different voices and different shapes, but it still resonates. It requires me to intuit more, to pay much more attention to non-verbal senses and emotional structures and to try to put them into words, rather than to follow the intellectual string of words themselves.

"Although our diseases are very different, I have felt what Floyd Skloot describes in his essay 'Thinking with a Damaged Brain,' in which he traces the ways his thought processes have been altered by the aftermath of a virus that ravaged his attention and memory: 'I must be willing to write slowly, to skip or leave blank spaces where I cannot find words that I seek, compose in fragments and without an overall ordering principle or imposed form. I explore and make discoveries in my writing now, never quite sure where I am going but willing to let things ride and discover later how they all fit together.'

"I do work more slowly. Of necessity, I place more faith in Tomorrow Me. When I stop writing, daunted by a place where I���m stuck, my energy plummets and I hand it off, knowing I���ll pick up the challenge on the next session....

"The dim semaphore through which my sentences arrive today leads to a strange by-product: I have less energy to worry about all the ways in which I might be wrong (though maybe age and confidence have also helped). In plodding along slowly, my voice has become clearer, at least in my own head. This slow writing forces me to make each word count."

Please take the time to read Huber's insightful essay in full (published online at Literary Hub), as this is just a small taste of it. I also recommend her brilliant collection Pain Woman Takes Your Keys & Other Essays from a Nervous System, discussed in this previous post.

"In order to keep me available to myself," wrote Audre Lord in The Cancer Journals, "and able to concentrate my energies upon the challenges of those worlds through which I move, I must consider what my body means to me. I must also separate those external demands about how I look and feel to others, from what I really want for my own body, and how I feel to my selves."

This is also a challenge for all of us, the sick and the well alike.

Words: The passages quoted above are from "Writing With and Through Pain" by Sonya Huber (Literary Hub, June 25, 2018) and The Cancer Journals by Audre Lorde (Aunt Lute Books, 1980). The poem in the picture captions is from New Ohio Review (No. 9, Spring, 2011). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: A gentle stroll by River Teign. The pen-and-ink drawing is by British book artist Helen Stratton (1867-1961).

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 702 followers