Cheryl B. Klein's Blog, page 19

February 17, 2011

Terrific Brooklyn Book Sale!

Next weekend, February 26 & 27, is my wonderful church's unbelievably wonderful BOOK SALE. I use a lot of positive adjectives on this blog, but I could spend all my favorite ones on this sale and still not say enough good things. The books are cheap -- $2 hardcovers, $2 trade paperbacks, $1 mass-market paperbacks; the selection is awesome -- our entire church basement, filled to bursting with every form of media, books fiction and nonfiction, DVDs & CDs & tapes, children's, YA, and adult; and the money all goes to a good cause -- said wonderful church, Park Slope United Methodist.

The sale runs from 8 to 4:30 on Saturday the 26th, 12:30-4:30 on Sunday the 27th. The church is located at the corner of 6th Ave. and 8th Street in Park Slope; take the the F to 7th Ave. or the R to 9th St. for subway access. If you want to clear out your shelves, you can donate books at the church on the following schedule:

February 21 (Monday) from 12 p.m.-6 p.m.February 24 (Thursday) from 7 p.m.-10 p.m.February 25 (Friday) from 10 a.m.-9 p.m.If you'd like to arrange a car pickup in the Park Slope vicinity, call Rick at (347) 538-7604. And if you need any more information, you can click here, but really, you should just COME. You will not regret it. And thank you.

The sale runs from 8 to 4:30 on Saturday the 26th, 12:30-4:30 on Sunday the 27th. The church is located at the corner of 6th Ave. and 8th Street in Park Slope; take the the F to 7th Ave. or the R to 9th St. for subway access. If you want to clear out your shelves, you can donate books at the church on the following schedule:

February 21 (Monday) from 12 p.m.-6 p.m.February 24 (Thursday) from 7 p.m.-10 p.m.February 25 (Friday) from 10 a.m.-9 p.m.If you'd like to arrange a car pickup in the Park Slope vicinity, call Rick at (347) 538-7604. And if you need any more information, you can click here, but really, you should just COME. You will not regret it. And thank you.

Published on February 17, 2011 17:28

February 16, 2011

The Proof Is in the Pudding

(Mmm. Pudding.)

And the proofs are also in my hands, as you can see here:

(I imagine y'all might be getting sick of my nattering about Second Sight, but I'm going to talk about this anyway, as it's a nice opportunity for you writers to see a little of the behind-the-scenes book manufacturing process.)

(I imagine y'all might be getting sick of my nattering about Second Sight, but I'm going to talk about this anyway, as it's a nice opportunity for you writers to see a little of the behind-the-scenes book manufacturing process.)

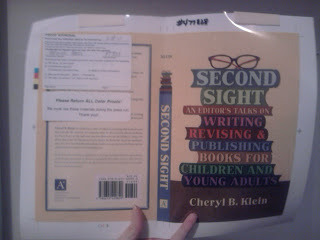

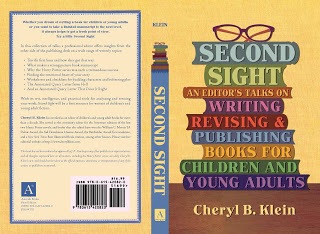

So: This is the cover proof, which I have to approve for color and final text. Both at work and here, the cover proofs come with clear plastic overlays, one for each of the various kinds of cover effects. Here I'm just getting a gloss coating, so there's just one overlay; but if I were getting, say, matte lamination along with spot gloss (aka "spot UV"), then there would be two overlays, one showing the matte layer, one showing the gloss layer, each one positioned precisely to show what areas of the color proof that effect would cover.

And then there can also be overlays for embossing, debossing, foil color #1, foil color #2, printing on foil . . . all the myriad ways in which you can bling up a book, for better or worse. Each individual effect costs money -- an additional three to eighteen cents per effect, per book (costs quoted off the top of my head), depending on the effect and the amount it's used and the print run and so forth -- which goes directly to the unit cost of the book. So the more effects a book has, the higher the unit cost, and the more expensive the book itself might be as well; but that can also pay off, if the effects result in more attention from buyers or a more attractive package overall.

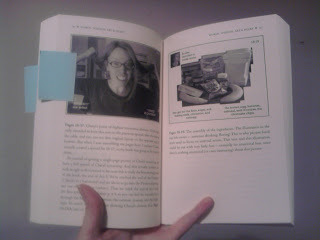

Here's something I don't see at work: an actual bound book proof for approval! At work we see "lasers" or "blues," which likewise provide an absolute last chance for any text changes, but which arrive either as loose pages printed on both sides of special laser paper, or on blueprint paper printed in signatures (hence the terms). I assume whether the proofs come bound or unbound depends on the printer and its arrangements with the production department. And I think I prefer unbound proofs, actually, as they're easier to lay flat, consider, and mark up.

Here's something I don't see at work: an actual bound book proof for approval! At work we see "lasers" or "blues," which likewise provide an absolute last chance for any text changes, but which arrive either as loose pages printed on both sides of special laser paper, or on blueprint paper printed in signatures (hence the terms). I assume whether the proofs come bound or unbound depends on the printer and its arrangements with the production department. And I think I prefer unbound proofs, actually, as they're easier to lay flat, consider, and mark up.

(Which is not to say I am not THRILLED with this as a proof: It's a book! A real book! If my unit cost had increased every time I squeed over this today, I could no longer afford to print it.)

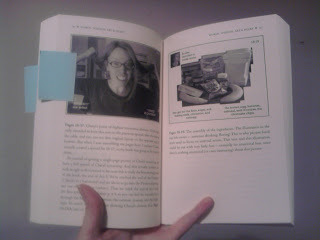

And here you can see the actual interior, showing a spread from "Words, Wisdom, Art and Heart." The pictures are printing very nicely, which was a big concern for me; sometimes you need heavier paper to prevent bleed-through, or more grayscale to render the tones of a photograph correctly, but that doesn't seem to be an issue here. I'm going to go through this proof page by page to confirm that all the pages are there, in order, and no lines have slipped or text gone missing; and then I have to sign and return both proofs to the printer.

And here you can see the actual interior, showing a spread from "Words, Wisdom, Art and Heart." The pictures are printing very nicely, which was a big concern for me; sometimes you need heavier paper to prevent bleed-through, or more grayscale to render the tones of a photograph correctly, but that doesn't seem to be an issue here. I'm going to go through this proof page by page to confirm that all the pages are there, in order, and no lines have slipped or text gone missing; and then I have to sign and return both proofs to the printer.

Then, in just under three weeks, it will be a real book, with the cover attached. I've set the official pub date as 3/11/11, by which date the books should have reached the warehouse and be available for delivery. (Ordering information to come soon.) Once again: Squee!

ETA, 2/17/11: The cover proof was fine, but I decided to make three corrections to the interior: one italicization that went wonky in the last round of proofing; one incorrect word I'd missed; and one fairly large typo I couldn't let stand. Cost of making these corrections: $52. Feeling like my book is that much more complete: Priceless.

And the proofs are also in my hands, as you can see here:

(I imagine y'all might be getting sick of my nattering about Second Sight, but I'm going to talk about this anyway, as it's a nice opportunity for you writers to see a little of the behind-the-scenes book manufacturing process.)

(I imagine y'all might be getting sick of my nattering about Second Sight, but I'm going to talk about this anyway, as it's a nice opportunity for you writers to see a little of the behind-the-scenes book manufacturing process.)So: This is the cover proof, which I have to approve for color and final text. Both at work and here, the cover proofs come with clear plastic overlays, one for each of the various kinds of cover effects. Here I'm just getting a gloss coating, so there's just one overlay; but if I were getting, say, matte lamination along with spot gloss (aka "spot UV"), then there would be two overlays, one showing the matte layer, one showing the gloss layer, each one positioned precisely to show what areas of the color proof that effect would cover.

And then there can also be overlays for embossing, debossing, foil color #1, foil color #2, printing on foil . . . all the myriad ways in which you can bling up a book, for better or worse. Each individual effect costs money -- an additional three to eighteen cents per effect, per book (costs quoted off the top of my head), depending on the effect and the amount it's used and the print run and so forth -- which goes directly to the unit cost of the book. So the more effects a book has, the higher the unit cost, and the more expensive the book itself might be as well; but that can also pay off, if the effects result in more attention from buyers or a more attractive package overall.

Here's something I don't see at work: an actual bound book proof for approval! At work we see "lasers" or "blues," which likewise provide an absolute last chance for any text changes, but which arrive either as loose pages printed on both sides of special laser paper, or on blueprint paper printed in signatures (hence the terms). I assume whether the proofs come bound or unbound depends on the printer and its arrangements with the production department. And I think I prefer unbound proofs, actually, as they're easier to lay flat, consider, and mark up.

Here's something I don't see at work: an actual bound book proof for approval! At work we see "lasers" or "blues," which likewise provide an absolute last chance for any text changes, but which arrive either as loose pages printed on both sides of special laser paper, or on blueprint paper printed in signatures (hence the terms). I assume whether the proofs come bound or unbound depends on the printer and its arrangements with the production department. And I think I prefer unbound proofs, actually, as they're easier to lay flat, consider, and mark up. (Which is not to say I am not THRILLED with this as a proof: It's a book! A real book! If my unit cost had increased every time I squeed over this today, I could no longer afford to print it.)

And here you can see the actual interior, showing a spread from "Words, Wisdom, Art and Heart." The pictures are printing very nicely, which was a big concern for me; sometimes you need heavier paper to prevent bleed-through, or more grayscale to render the tones of a photograph correctly, but that doesn't seem to be an issue here. I'm going to go through this proof page by page to confirm that all the pages are there, in order, and no lines have slipped or text gone missing; and then I have to sign and return both proofs to the printer.

And here you can see the actual interior, showing a spread from "Words, Wisdom, Art and Heart." The pictures are printing very nicely, which was a big concern for me; sometimes you need heavier paper to prevent bleed-through, or more grayscale to render the tones of a photograph correctly, but that doesn't seem to be an issue here. I'm going to go through this proof page by page to confirm that all the pages are there, in order, and no lines have slipped or text gone missing; and then I have to sign and return both proofs to the printer. Then, in just under three weeks, it will be a real book, with the cover attached. I've set the official pub date as 3/11/11, by which date the books should have reached the warehouse and be available for delivery. (Ordering information to come soon.) Once again: Squee!

ETA, 2/17/11: The cover proof was fine, but I decided to make three corrections to the interior: one italicization that went wonky in the last round of proofing; one incorrect word I'd missed; and one fairly large typo I couldn't let stand. Cost of making these corrections: $52. Feeling like my book is that much more complete: Priceless.

Published on February 16, 2011 21:01

February 15, 2011

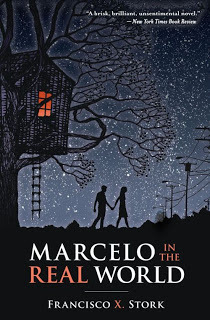

Q&A: Francisco X. Stork, author of MARCELO IN THE REAL WORLD

Earlier this month, Francisco X. Stork's much-acclaimed

Marcelo in the Real World

came out in paperback. Francisco and I are working on our third book together (after Marcelo and

The Last Summer of the Death Warriors

), but I had never actually hosted him for a Q&A here, so I asked him to answer a few questions for me, and he was kind enough to agree.

Earlier this month, Francisco X. Stork's much-acclaimed

Marcelo in the Real World

came out in paperback. Francisco and I are working on our third book together (after Marcelo and

The Last Summer of the Death Warriors

), but I had never actually hosted him for a Q&A here, so I asked him to answer a few questions for me, and he was kind enough to agree. Could you tell us a little bit about how Marcelo came to be?

Marcelo had a long journey before it came to be in its final form. The first version I wrote was not about Marcelo but about his mother, Aurora. In this story, Aurora enters Marcelo's room a year after his death and discovers his journals. The journals reveal a very special young man. It was when transcribing the journals of Marcelo that his voice became very powerful. It was as if Marcelo was urging me to write his story. So I wrote about him, a book that I initially intended as an adult book. It had Marcelo traveling to Mexico in search of Ixtel, the young woman whose picture he discovers in his father's files. Faye Bender, my agent, sent this version to adult publishers without success. I then decided to rewrite some of it and we sent it to young adult publishers and this is how the version you got came across your desk. As you know, there were major revisions after you accepted it. The trip to Mexico was canned. The story became more "local." I think that with your help, I rewrote about sixty percent of the book. [CK note: For my own account of the editorial process, click here.]

The other thing I want to mention is that I never set out to write a book about a young man with Asperger's syndrome. I created Marcelo, paying attention to the voice that was presented to me, and only later discovered that someone like him would probably be diagnosed with something. It was then that I connected him to Asperger's syndrome.

Has there been a pattern to where your books begin for you? That is, do they usually begin with a philosophical idea to explore, or the characters, or the situation – or is it different with every book? Once you have the initial seed, whatever it is, where do you go from there?

It is very difficult to tell just exactly how the seed for a novel is planted or where the seed comes from. It's a combination of philosophical idea and voice. In Marcelo, for example, I asked myself what would happen if a very innocent, saintly young man discovered a file that would show him the evil and suffering of the world. Once I started playing with this idea, Marcelo's unique voice came into being. Then the philosophical idea was put aside and the character and the story took over. In the case of Death Warriors, I asked myself what would happen if I put together two very different young men, one who was very down-to-earth, practical and consumed by revenge, and the other, idealistic, philosophical and also gravely ill. Then the voices of Pancho and D.Q. came into being and they led the way. It is very important to me to let character become the driving force of the book.

You often write beautifully on your blog about the act of writing itself. What is your personal writing process like? Do you draft longhand, or on a computer? Write a full draft and then revise, or revise as you go? Do you plan books out, or write as the characters direct you? Do you have a conscious process for developing your characters, or do they just reveal themselves as you write?

I have a full-time job working as an attorney for a state agency that develops affordable housing. The day job has forced me to find a compatible writing process, which is not easy. When I start writing a novel, I need to accept the fact that the finished product is three to four years down the line. So I strive for patience and I try to be kind to myself. If I can write a page a day, that's wonderful. Some days I write five pages and some days I don't write anything. I usually write directly on my laptop and I try to keep an attitude of play about the writing. Being playful for me means that I follow where the characters take me with only a vague notion of where I'm going or what I'm going to write about tomorrow. Somehow tomorrow always takes care of itself. I usually try to develop the character's voice or personality before I start writing and that happens over a long period of gestation. During that period I will often try out different voices in a separate journal. But, of course, characters grow and develop as I write about them and they quite often surprise me.

We're two years out now from the publication of Marcelo, and almost three years from when you finished writing and revising it. What is your relationship to the characters at this point? Do they still feel present for you, or have they faded away a bit in favor of the people you're writing now?

The characters from Marcelo are still very present for me. Every once in a while I'll ask myself: What would Marcelo do? It's a terrible burden to create characters that are better human beings than you can ever hope to be! Now and then I'll read a passage from Marcelo for inspiration (usually one of the dialogues with Rabbi Herschel). Reading Marcelo at this point is like reading something written by someone else.

Do you know what the characters from Marcelo are doing now? [This next passage, with Francisco's answer, is blanked out to avoid spoilers and for readers who might have their own visions of the action. Highlight to read:] In my mind, Marcelo finished his last year of high school. He had some fitting-in problems but he managed okay. His mom and dad unfortunately got divorced and Marcelo has had to deal with that. He is going to nursing school in New Hampshire. He visits Jasmine and Amos every weekend and is currently trying to convince Amos to buy some ponies. He and Jasmine are in love.

You wrote once on your blog about Marcelo, "the role of religion in the book is in the asking certain type of questions when the asking is done with mind, heart, body and soul." I would say all your books reflect this kind of religion – the asking of those big questions, which come to occupy the characters' and the book's whole heart. To what extent are you conscious of those questions when you're writing the book, and to what extent do you discover them later and weave them into the revision?

Let's just say that I'm semi-conscious of the big questions during the first draft. I know the big questions are there and I've created young people capable of asking these questions, but because I'm writing a novel and not a philosophical essay, I've let the characters and the story take over. Then, after I finish the first draft, you have asked me to write a letter that addresses the big themes in the book. It is through this letter that I become aware of those big questions and how I was trying to deal with them. Once this awareness is present, you and I can revise the novel in such a way that the big questions become part of the flesh and blood of the book.

What are you reading now for pleasure?

Whenever I'm in the process of writing, like I am now, I like to reread those authors who have the kind of language and rhythms and characters that are inspiring. For me, the work of people like Annie Dillard, Flannery O'Connor, Dostoievski, Cervantes always do the trick. I also read every day something from or about a world religion.

What makes you tell stories?

I've always liked Flannery O'Connor's response to the question: Why do you write? "Because it's worse when I don't," she answered. So it is for me. Telling stories is part of why I came into this world and so when I don't write, I have a sense that I'm not quite living up to my end of the bargain. Of course, writing is not the only reason (or the most important) why I came into this world, so I try not to be anxious about the process of writing. I do what I can. I try my best. What else can I do? There is also a social element connected to the telling of stories. I tell stories about intelligent, sensitive Latino young people who in many ways serve as role models for other young people and that fulfills a sense of personal and social responsibility.

Thank you, Francisco!

Published on February 15, 2011 21:33

February 6, 2011

More on SECOND SIGHT

The Annotated Table of Contents and Introduction are now live on my website.

ETA: The "Introduction" link was broken earlier; it should be fine now. Thanks to those who brought the mistake to my attention!

ETA: The "Introduction" link was broken earlier; it should be fine now. Thanks to those who brought the mistake to my attention!

Published on February 06, 2011 21:34

February 3, 2011

Blogiversary and Book Cover!

Today, February 4, is a pretty significant day in my personal yearly calendar. In 2003, my dear Grandma Carol passed away. In 2005, I rejuvenated this blog, which had lain dormant for exactly two years. In 2006, I celebrated my first blogiversary, and I've tried to mark it every year since with a few brief words.

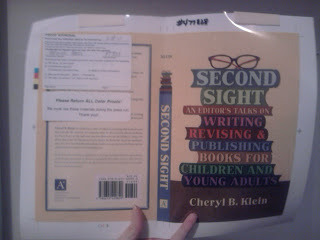

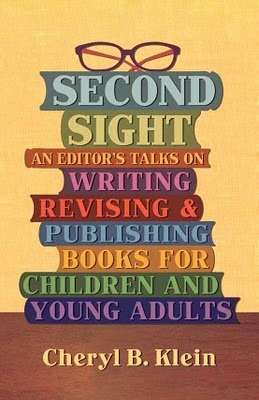

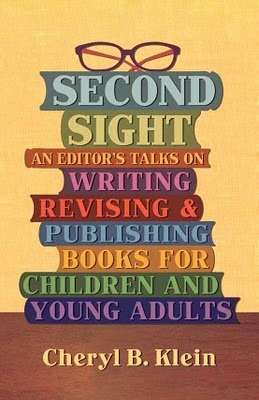

And in 2011, this is going to print:

And this is very much the culmination of all the February 4ths that have come before it: Second Sight is dedicated to the memory of my grandma (as well as my papa), and it would never have come about without this blog -- quite literally, as the blog led to my website led to writerly interest led to more talks led to the idea led to Kickstarter led to this finally happening. Thanks to all of you for your support through the years, on the blog and for the book: It is truly, deeply appreciated.

The cover was designed by Whitney Lyle, who is newly on staff at Scholastic, with much gadflyish art direction from me. (Seriously, editor + author + client in one person = designer's worst nightmare, but she has borne it with good grace.) I've been looking at versions of this cover for about three months now, and somehow posting it here and on Facebook today, e-mailing it to my book fulfillment people for my online shop, getting ready to send it to press -- it has finally become really real. Which I find a wee bit terrifying, I confess. But I so admire all you writers and illustrators for your daring and bravery, making things you imagined real in the world; and I'm excited to finally be taking that step myself at last. Hooray!

And in 2011, this is going to print:

And this is very much the culmination of all the February 4ths that have come before it: Second Sight is dedicated to the memory of my grandma (as well as my papa), and it would never have come about without this blog -- quite literally, as the blog led to my website led to writerly interest led to more talks led to the idea led to Kickstarter led to this finally happening. Thanks to all of you for your support through the years, on the blog and for the book: It is truly, deeply appreciated.

The cover was designed by Whitney Lyle, who is newly on staff at Scholastic, with much gadflyish art direction from me. (Seriously, editor + author + client in one person = designer's worst nightmare, but she has borne it with good grace.) I've been looking at versions of this cover for about three months now, and somehow posting it here and on Facebook today, e-mailing it to my book fulfillment people for my online shop, getting ready to send it to press -- it has finally become really real. Which I find a wee bit terrifying, I confess. But I so admire all you writers and illustrators for your daring and bravery, making things you imagined real in the world; and I'm excited to finally be taking that step myself at last. Hooray!

Published on February 03, 2011 21:03

January 30, 2011

A Ramble: Kindling, Including a Method for Dealing with Writerly Dramatic Despair

8:25 p.m.: "Kindling" has a lot of meanings for me right now. I am just home from Kindling Words, the annual and extraordinary writers', illustrators', and editors' conference in Vermont. I have my Kindle, loaded with manuscripts I ought to be reading at this moment; but I am so tired from the conference and January in general that my brain feels like kindling . . . the little pieces of wood you'd feed to a fire to help it grow. Or is that the right word? I don't know. My mind is mush.

Perfect time to write a Ramble, yes?

(Tinder? Timber? Tender timber? I haven't built a fire in forever.)

I think these will turn out to be monthly Rambles rather than weekly ones, as promised at the beginning of the year, because clearly when it comes to writing weekly ones, I vacuum. But monthly, surely, I can manage.

(Say this all together now: Ha! Ha!)

Kindling Words, for all that it has turned my brain to twigs, was as lovely as the first time I went. . . . A different kind of loveliness, the loveliness of an old friend and different responsibilities and expectations, rather than the oh-wow! discovery of everything it had to offer the first time I attended in 2008. I led the editorial strand this year, which is for editors only, and as part of that, I gave a speech on insiders and outsiders, eels and goldfish (long story), to the whole group, expanding on some of the themes and ideas in "Morals, Muddles," among other things. I wanted this speech to be VERY IMPRESSIVE, to be worthy of KW and all the great writers there, but because of that, I had a terrible time getting started or even settling on a topic -- for a long time I was half writing this insider speech and half writing a speech on the rights of readers vs. authors (which will doubtless show up later somewhere eventually, probably here). I've written enough speeches now, especially under pressure, that I felt confident that eventually the speech would come together as it should (a normal step in my writing process, Overconfident Orating); but by Monday, I had so much (self-imposed) pressure on myself to be VERY IMPRESSIVE that I slipped into another normal part of my writing process, which is Dramatic Despair. In dealing with it, I think I hit upon a technique that may be useful to other writers, so I share it here:

WRITE THE ABSOLUTE WORST THING YOUR IMAGINARY AUDIENCE COULD SAY ABOUT YOUR WORK. Because then the absolute worst thing will be out there, SAID, and you won't need to fear it any more; and that will give you the freedom to keep writing what you have to write, and damn the torpedos, because you've already identified them and taken away their sting. (This is kind of like having a Day of Vacuum in print form: You defang it by acknowledging it and turning its venom to your own ends.) For me, this took the form of writing a draft of my speech in quasi-poetic form, where I led the audience through a history of all my failed attempts to write this damn speech, and I made it into a sort of theatrical piece, where various luminaries in the audience stood up and shouted "NOT GOOD ENOUGH!" at me at various points. And I was then going to turn it around at the end to say that KW is a conference where things are always good enough, because it's an atmosphere of love in which we do our best work, and have everybody chant "GOOD ENOUGH" together at the finale. Cheesy, yes, but once I had articulated the idea of [writer-whose-work-I-adore-name redacted] and [ditto] and [ditto] standing up to tell me I was awful, contrary to my attempts to be VERY IMPRESSIVE . . . Well, nothing I wrote was actually going to be so bad that those particular people were going to do that, because of their good manners, if nothing else. And recognizing that (and sleeping on it a night) freed me up to write the speech I wanted to write, which, while perhaps not VERY IMPRESSIVE, at least had some good ideas and good lines and an interesting arc to it, and was satisfactory.

SO: If you are finding yourself stuck out of fear of what your editor or your mother or critique group or Kirkus will say about your work, write the absolute worst thing you can imagine them saying, in all its awful, particular, snotty, snarky glory. Then recognize that actually they will not say that, either because they love you (your editor, mother, and critique group, hopefully), or because your work is not actually that bad (this is actually true: you are just in a fit of Dramatic Despair). (And if it IS that bad, your editor and critique group will help make it better before Kirkus ever sees it.) And you have plenty of time, and it will all be okay. And, really, it will.

Emily Jenkins (E. Lockhart) led the writers' strand at KW, which was a great thrill for me because I SO love her work. . . . I've discovered that if I first fall in love with a writer's work when I'm reading it for fun, I tend to be a little bit -- not scared of the writer, certainly, if I meet them professionally later; but I have the same feeling I did when I was a little girl meeting the writers at my papa's children's literature festivals: the shyness at how much time I've spent in their worlds vs. how little they know me, the awe at all the people who live in their brains and everything they're able to accomplish in their books, the gratitude for the experiences and thoughts and pure pleasure I've taken in those books, the squeeness of meeting them at last. And it still takes me a while to get over that, though I tend to be able to fake it till I make it pretty well now, I think. I admire Emily's work (I guess I get to call her Emily now) because it's so tough-minded, really: People always suffer real emotional consequences and complications in her books -- the endings are never unalloyed happiness. (Well, maybe in Fly on the Wall, which I just finished today. But there's an awful lot of alloying to get through before then, including the heroine spending a week as a fly in the boys' locker room. Tell me that isn't alloy.) And her heroines have very discursive minds, which clearly I appreciate, and they have way MORE on those minds than just boys, even in the Ruby Oliver books, where boys are in the titles. And they are both feminist and funny as hell. I want to reread The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks now, as well as the newest Ruby Oliver title, and go back and pick up all her middle-grade and picture books too.

Ten minutes left in this hour-long Ramble. What else do I want to say? There is a lot of good editorial talent coming up at Candlewick and Chronicle and HMH (three of the five houses whose editors attended this year) -- keep an eye on the editorial assistants and young editors at all three of those houses, because good things will be coming from them. Andrea Tompa once again brought her Graham Cracker Goodness, which disappeared from the baked-goods table in about an hour flat. We have SO MUCH SNOW here in New York, and more on the way. I got to wear my beloved eBay evening gown to the masquerade ball on Friday night, and I was snowed on while sitting in a hot tub on Saturday. These were both wonderful things.

Emily shared John Gardner's Five Questions from On Becoming a Novelist:

1. Does it create a vivid and continuous dream?

2. Does it exhibit authorial generosity?

3. Is it emotionally and intellectually significant?

4. Is it elegant and efficient?

5. Is it strange?

If your answer to any of these questions is no, GET TO WORK.

(Sticks.)

Perfect time to write a Ramble, yes?

(Tinder? Timber? Tender timber? I haven't built a fire in forever.)

I think these will turn out to be monthly Rambles rather than weekly ones, as promised at the beginning of the year, because clearly when it comes to writing weekly ones, I vacuum. But monthly, surely, I can manage.

(Say this all together now: Ha! Ha!)

Kindling Words, for all that it has turned my brain to twigs, was as lovely as the first time I went. . . . A different kind of loveliness, the loveliness of an old friend and different responsibilities and expectations, rather than the oh-wow! discovery of everything it had to offer the first time I attended in 2008. I led the editorial strand this year, which is for editors only, and as part of that, I gave a speech on insiders and outsiders, eels and goldfish (long story), to the whole group, expanding on some of the themes and ideas in "Morals, Muddles," among other things. I wanted this speech to be VERY IMPRESSIVE, to be worthy of KW and all the great writers there, but because of that, I had a terrible time getting started or even settling on a topic -- for a long time I was half writing this insider speech and half writing a speech on the rights of readers vs. authors (which will doubtless show up later somewhere eventually, probably here). I've written enough speeches now, especially under pressure, that I felt confident that eventually the speech would come together as it should (a normal step in my writing process, Overconfident Orating); but by Monday, I had so much (self-imposed) pressure on myself to be VERY IMPRESSIVE that I slipped into another normal part of my writing process, which is Dramatic Despair. In dealing with it, I think I hit upon a technique that may be useful to other writers, so I share it here:

WRITE THE ABSOLUTE WORST THING YOUR IMAGINARY AUDIENCE COULD SAY ABOUT YOUR WORK. Because then the absolute worst thing will be out there, SAID, and you won't need to fear it any more; and that will give you the freedom to keep writing what you have to write, and damn the torpedos, because you've already identified them and taken away their sting. (This is kind of like having a Day of Vacuum in print form: You defang it by acknowledging it and turning its venom to your own ends.) For me, this took the form of writing a draft of my speech in quasi-poetic form, where I led the audience through a history of all my failed attempts to write this damn speech, and I made it into a sort of theatrical piece, where various luminaries in the audience stood up and shouted "NOT GOOD ENOUGH!" at me at various points. And I was then going to turn it around at the end to say that KW is a conference where things are always good enough, because it's an atmosphere of love in which we do our best work, and have everybody chant "GOOD ENOUGH" together at the finale. Cheesy, yes, but once I had articulated the idea of [writer-whose-work-I-adore-name redacted] and [ditto] and [ditto] standing up to tell me I was awful, contrary to my attempts to be VERY IMPRESSIVE . . . Well, nothing I wrote was actually going to be so bad that those particular people were going to do that, because of their good manners, if nothing else. And recognizing that (and sleeping on it a night) freed me up to write the speech I wanted to write, which, while perhaps not VERY IMPRESSIVE, at least had some good ideas and good lines and an interesting arc to it, and was satisfactory.

SO: If you are finding yourself stuck out of fear of what your editor or your mother or critique group or Kirkus will say about your work, write the absolute worst thing you can imagine them saying, in all its awful, particular, snotty, snarky glory. Then recognize that actually they will not say that, either because they love you (your editor, mother, and critique group, hopefully), or because your work is not actually that bad (this is actually true: you are just in a fit of Dramatic Despair). (And if it IS that bad, your editor and critique group will help make it better before Kirkus ever sees it.) And you have plenty of time, and it will all be okay. And, really, it will.

Emily Jenkins (E. Lockhart) led the writers' strand at KW, which was a great thrill for me because I SO love her work. . . . I've discovered that if I first fall in love with a writer's work when I'm reading it for fun, I tend to be a little bit -- not scared of the writer, certainly, if I meet them professionally later; but I have the same feeling I did when I was a little girl meeting the writers at my papa's children's literature festivals: the shyness at how much time I've spent in their worlds vs. how little they know me, the awe at all the people who live in their brains and everything they're able to accomplish in their books, the gratitude for the experiences and thoughts and pure pleasure I've taken in those books, the squeeness of meeting them at last. And it still takes me a while to get over that, though I tend to be able to fake it till I make it pretty well now, I think. I admire Emily's work (I guess I get to call her Emily now) because it's so tough-minded, really: People always suffer real emotional consequences and complications in her books -- the endings are never unalloyed happiness. (Well, maybe in Fly on the Wall, which I just finished today. But there's an awful lot of alloying to get through before then, including the heroine spending a week as a fly in the boys' locker room. Tell me that isn't alloy.) And her heroines have very discursive minds, which clearly I appreciate, and they have way MORE on those minds than just boys, even in the Ruby Oliver books, where boys are in the titles. And they are both feminist and funny as hell. I want to reread The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks now, as well as the newest Ruby Oliver title, and go back and pick up all her middle-grade and picture books too.

Ten minutes left in this hour-long Ramble. What else do I want to say? There is a lot of good editorial talent coming up at Candlewick and Chronicle and HMH (three of the five houses whose editors attended this year) -- keep an eye on the editorial assistants and young editors at all three of those houses, because good things will be coming from them. Andrea Tompa once again brought her Graham Cracker Goodness, which disappeared from the baked-goods table in about an hour flat. We have SO MUCH SNOW here in New York, and more on the way. I got to wear my beloved eBay evening gown to the masquerade ball on Friday night, and I was snowed on while sitting in a hot tub on Saturday. These were both wonderful things.

Emily shared John Gardner's Five Questions from On Becoming a Novelist:

1. Does it create a vivid and continuous dream?

2. Does it exhibit authorial generosity?

3. Is it emotionally and intellectually significant?

4. Is it elegant and efficient?

5. Is it strange?

If your answer to any of these questions is no, GET TO WORK.

(Sticks.)

Published on January 30, 2011 18:39

January 24, 2011

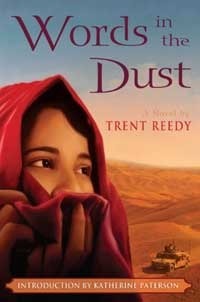

Behind the Book: WORDS IN THE DUST, + An Opportunity to Help Afghan Women

Sometimes I receive manuscripts that I don't want to love. Something in the agent's pitch or the query letter rubs me the wrong way; I know the genre or the subject matter will make it a terrible uphill climb to and in the marketplace; it is the least commercially appealing subject ever (incest, kitten torturers). I still read these manuscripts, of course, because quality writing will trump everything else, but even more than usual, I go in thinking, Convince me.

Sometimes I receive manuscripts that I don't want to love. Something in the agent's pitch or the query letter rubs me the wrong way; I know the genre or the subject matter will make it a terrible uphill climb to and in the marketplace; it is the least commercially appealing subject ever (incest, kitten torturers). I still read these manuscripts, of course, because quality writing will trump everything else, but even more than usual, I go in thinking, Convince me.And though I'm almost ashamed to admit it now, one of these manuscripts was Words in the Dust. When I received the agent's pitch letter in late September 2009, it told me that it was the story of a Muslim girl in modern-day Afghanistan, which DID sound exactly right for me and the Arthur A. Levine Books imprint; given our international focus, and the fact that I'd just published Sara Lewis Holmes's Operation Yes (about Air Force kids with parents serving in Iraq and Afghanistan), it seemed like a good fit. But the letter then went on to explain that it was written by a guy from Iowa, with the decidedly un-Central Asian name of "Trent Reedy," who had served in the National Guard in Afghanistan. I knew this agent had good taste and knew my tastes as well, that she wouldn't be steering me wrong; but having long watched the kidlit authenticity wars with a fascinated and wary eye, I thought, Well, that just sounds like nine kinds of trouble, as I put the manuscript in the e-reader queue.

A couple weeks later, I handed my e-reader to Christina McTighe, a lovely young woman (and occasional commenter here) then working for me as an intern, and pointed to the manuscript onscreen. (I do look at every manuscript myself, but given the volume of manuscripts and the loneness of me, smart interns are enormously helpful for triage.) I said, "Would you take a look at this? I have my doubts about it, but let me know what you think."

And she came back a few hours later and said, "You HAVE to read this. I love it. It's really, really, really good."

Huh, I thought. Who'da thunk? That was the most enthusiastic recommendation Christina had given anything in the six months she'd been interning with me; like the agent, she had good taste and knew my taste, and so that was two people who swore to the quality of this book. On the subway home that evening, as I was scrolling through the manuscripts on my e-reader, I saw the title and remembered her endorsement. So I clicked on the document. . . .

And from the very first page, it was so exact about the heat and light and dust in Afghanistan, so honest about the good and bad, the dreams and frailties, in every single one of its characters, that I fell in love with the book too. Its heroine and narrator is Zulaikha, a thirteen-year-old girl with a congenital cleft lip, which makes the mean boys in her village call her "Donkeyface." Her stepmother, Malehkah, likewise seems terminally disgusted by her, and no one, Zulaikha included, believes they'll ever be able to find her a husband--the only way most Afghan women can leave their father's house. But Zulaikha has a good attitude despite these difficulties, and her inner strength, unfailing hope, and occasional (internal) sarcastic remark instantly endeared her to me. When American soldiers arrived in her village, I shared her distrust and fear; when they offered to provide surgery to fix her cleft lip, I felt her joy and wonder—but that was a road not unmarked by trouble, and I held my breath with her through each turn in her fortunes. There was plenty of other action in the book as well: Zulaikha's expertly rendered shifting relationships with her brothers; the wedding of her beloved older sister, Zeynab; her learning to read, thanks to a woman in her village, and her amazement at finding her feelings expressed in Afghan poems written eight centuries before she was born . . . all the way through to the heartbreaking yet optimistic ending, with its hope for the future anchored in the pain of Zulaikha's growth in the story.

With all that, perhaps the author's most impressive accomplishment for me was his characterization of Zulaikha's father, who loves his family and works with the Americans on construction projects, but who also takes it absolutely for granted that his wife and daughters should obey him unquestioningly, and that he has every right to hit them if he wants. I'm a twenty-first century feminist to the core, so this should have put me off completely, and yet I loved this man, the same way Zulaikha does, because I saw and understood all of him, both his tenderness and his firmness. And I loved the author and book, as little as I knew them then, for not pulling any punches in showing us who all these characters were: revealing both the good and the bad, and thus ending up at real. I was reading the manuscript at just the time President Obama was performing his 2009 review of our Afghanistan policy, and when I heard the president's decision on NPR, my first thought was, "But what will happen to Zulaikha?" It took me a moment to remember she was mostly fictional (see the Books page on Trent's website or this wonderful article in the Los Angeles Times for the remarkable true story behind the book); but my heart ached still for the real-life girls and women of Afghanistan, and for that reason as well as all the others, I knew I had to publish this.

In the weeks that followed, I put the machinery in motion to accomplish that. I talked to Arthur and our publisher and sales and marketing staff. I called the agent, Ammi-Joan Paquette, who was kind enough to put me in touch with Trent himself. We had a long talk one evening, after he'd finished teaching high school English for the day; and his obvious humility and good heart, his understanding of the issues surrounding his writing this book, and his eagerness to do everything he possibly could to make the manuscript as strong and as culturally right as it could be, convinced me that this was an author and book worth fighting for. (Not to mention his passion, when I asked him what he thought we should do for Afghanistan now, and he paused and said, "Uh, how much time do you have?") I was lucky enough to be Trent's first choice for an editor too, and in mid-December, we concluded the deal for the book.

Given the timeliness of the Afghanistan setting, we decided we wanted to publish Words in the Dust as soon as we possibly could without sacrificing full fact-checking or quality. So I went straight from the submitted manuscript into line-editing, which I rarely do; and at the same time, Trent and I started looking for vetters and other resources to verify those aspects of the text that didn't come from his personal experience in-country. We found two wonderful Afghan ladies now living in the U.S. who read the book for us and sent us their comments—one of them through the organization Women for Afghan Women, whose emphasis on educating and empowering Afghan women and children became an inspiration for us both. (Trent was a hero throughout this process, I want to add, working full-time as a teacher, play director, and prom sponsor, and yet still revising intensively.) Trent quoted a number of Afghan poems in the book, and rather than using the flowery, outdated Victorian translations that were in the public domain, I commissioned new versions from Roger Sedarat, a professor of creative writing and translation at Queens College, so the language would hold the same magic for modern English-language readers as it does for Zulaikha. And Katherine Paterson, who had long served as a mentor to Trent and an author idol for me, agreed to write an introduction, where she called the book a "beautiful and often heartbreaking tale."

And now, many months later, Words in the Dust is in stores, with strong first reviews from Booklist ("deeply moving"), Publishers Weekly ("a nuanced look at family dynamics and Afghan culture"), Kirkus ("both heartwrenching and timely"), and the Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books ("Readers will readily find themselves rooting for Zulaikha in this simply told yet thoughtful story"). Trent spoke at ALA Midwinter a couple weekends ago, and I'm told his talk about Afghanistan and the real Zulaikha moved some people to tears.

I'm going to be blunt here: For all this, and for everything else this book has going for it—its amazing quality and heart; the kind words from Katherine and Suzanne Fisher Staples; the enthusiasm of Scholastic's sales, publicity, and marketing staff, which has truly thrown themselves behind it—it is still the kind of book that often has a hard row to hoe in the marketplace. Why? Well, an Afghan girl with a cleft lip is not an automatic sell in a book world filled with crash-bang adventure and paranormal hullabaloo. The airwaves are filled with anti-Muslim and anti-Afghanistan sentiment, which will close a certain segment of people off to Zulaikha before they even pick up the book (if they ever pick up a book); and if readers can't absorb a few non-English words or deal with non-American or non-Christian customs, well, it would not be an easy or enjoyable read for them.

But I believe passionately that for those who do find the book and allow themselves to be open to it, Words in the Dust is a book they'll love, and a book that can change hearts and minds in the very best way possible: forming a connection with someone different from you by hearing their story. And to get the word out about it, I'm making the following offer:

For every person who "Likes" the Words in the Dust page on Facebook, and/or retweets the link and hashtag below on Twitter, I will donate $1 of my own money to Women for Afghan Women, up to a maximum aggregate amount of $500. Trent is already donating ten percent of his proceeds from the book to the organization, up to a maximum aggregate amount of $10,000, and I'm delighted to be able to further help the cause. Also, this is money that I'm offering personally, on my own initiative; this effort hasn't been suggested or sponsored by Trent or Scholastic in any way, and they are in no way liable for any matters related to this donation.

If you'd like to take part, please just click over to Facebook or Twitter and include the information below. (Remember, you must include the #WordsintheDust hashtag in Twitter to be counted—I don't have any way to keep track of the mentions otherwise!)

The book's Facebook page: Words in the Dust fan page (It has 20 fans at the time I'm posting this, for the record.)The bit.ly link to this post: http://bit.ly/hluSgKThe Twitter link for retweeting: RT to donate $1 for Afghan women in honor of Trent Reedy's WORDS IN THE DUST! http://bit.ly/hluSgK #WordsintheDustTrent's website: http://www.trentreedy.comThank you for your interest and participation, and I hope very much that you read and enjoy the book.

The book on IndieBound | Amazon | B&N | Borders | Powells

Published on January 24, 2011 05:00