Brent Hartinger's Blog, page 3

January 19, 2017

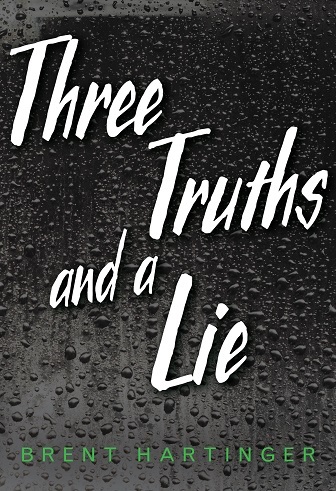

THREE TRUTHS AND A LIE Was Just Nominated for an Edgar Award!

What great news! My novel Three Truths and a Lie (a gay teen mystery/thriller) was just nominated for an Edgar Award! That’s the top award in the mystery genre, a little bit like the Oscar for mystery writers, so I couldn’t be happier.

Here’s the book trailer:

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

January 12, 2017

Update: GEOGRAPHY CLUB (the Movie) is Back Up on iTunes, etc.

A lot of people have written to ask me about the availability of Geography Club, the 2013 feature film adaptation of my first novel. For a time, it wasn’t available for download.

Well, it’s finally back up, on iTunes, Amazon, Amazon Prime, Full Screen, and other places!

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

January 10, 2017

I Loved Netflix’s THE OA (Including the Ending). Here’s Why:

Netflix recently debuted a very strange new TV series, The OA, and reaction to the show has been somewhat mixed, especially the esoteric ending, which a lot of people find unsatisfying. I’ve heard people say it’s “ambiguous” and “there’s no there there.” People are comparing the show to TV disasters like Twin Peaks and Lost. And in fact, there have a whole bunch of shows with vibes somewhat similar to The OA, and I’ve mostly been disappointed in them all: The Whispers, Touch, Believe, and on and on.

But as for The OA, I loved it. And I completely disagree that the ending doesn’t hold together. Here’s my take:

The OA is, ultimately, a show about human connection. A woman, Prairie, who has been missing for seven years suddenly returns to her family. But it’s like the world stopped moving when she left: her parents are shells of their former selves, and even the half-constructed houses in her old neighborhood are unfinished (due to the financial meltdown of 2007).

The OA is, ultimately, a show about human connection. A woman, Prairie, who has been missing for seven years suddenly returns to her family. But it’s like the world stopped moving when she left: her parents are shells of their former selves, and even the half-constructed houses in her old neighborhood are unfinished (due to the financial meltdown of 2007).

But Prairie, who was blind before, can see now.

Prairie won’t tell her parents (and the police) the details of her seeming abduction, or how she came to see — much to their frustration. At this point, everyone in the show is completely disconnected from each other — including the motley collection of neighbors and a teacher that Prairie comes in contact with.

But these four locals are strangely drawn to Prairie’s strange charisma, and they gather together in an abandoned house. Satisfied that they all number five, which is important for some reason, Prairie starts to tell them her story.

She explains how she once lived in Russia, with a father with whom she was very close. But she had a near-death experience, and a deity in the afterlife gave her the choice to return to life, taking her vision in the process (to “protect” her). Later, Prairie’s Russian father is killed, furthering her sense of isolation and disconnection with the world. Even Prairie ultimately being adopted by an American family didn’t change things, because they mostly medicated her, in order to make the strange, otherworldly aspects of her personality go away.

Then Prairie recounts exactly how she was kidnapped: she and four other people were kept captive in the basement of a crazy scientist who was researching life after death. They were all held in Plexiglas chambers where they could see each other, and talk, but not touch. When one of them, Homer, is temporarily released (to help the scientist replace a dead prisoner), he is so overwhelmed by his “freedom,” and his desperation to be touched, that he blows his chance at escape.

Eventually, out of frustration and desperation, the five prisoners begin to develop a strange dance-like ritual where it seems like, working together, they can even cure death.

Meanwhile, in the present, the four people fascinated by Prairie’s story begin to develop a strong sense of connection. They start to stand up for themselves in their own lives, and take responsibility for their actions.

In an effort to rescue her friends still back trapped by the scientist, Prairie teaches the four the same dance ritual she and the others perfected in the Plexiglas cell.

And then comes the ending of the season. The four people listening to Prairie learn that she is, in fact, crazy. The story she tells? None of it happened. (Or did it? Is someone trying to stop her true story from getting out? That’s clearly the question for season two.)

Convinced she lied, the four listeners are devastated. Demoralized, their lives all fall apart again. They are angry with Prairie, and as disconnected from the rest of the world as ever — and even with each other. They might as well be behind Plexiglas themselves, completely cut off.

Meanwhile, Prairie still insists her story was real. But her connection with the others has been broken. Convinced she can no longer save her imprisoned friends, she starts to go genuinely crazy. All seems truly lost.

But then the four friends are at the high school when a random shooter (no doubt inspired by the soullessness of the surrounding town) starts to attack the school cafeteria.

The friends are all powerless to stop the shooter, but they all see each other and have a moment of connection. They remember Prairie’s crazy story, and think: Well, why not try her crazy dance?

The friends are all powerless to stop the shooter, but they all see each other and have a moment of connection. They remember Prairie’s crazy story, and think: Well, why not try her crazy dance?

They do. At the same time, Prairie, who is back home, senses something. Desperate for human connection, and sensing something happening, she runs for the school. She stops at the glass window, looking at the cafeteria. But she’s still behind glass! She still can’t touch them — she can see the others, but she is still unable to touch them, or join them.

Meanwhile, the four friends continue their strange dance. They momentarily distract the shooter, enabling someone else to grab the gun. It works! The four friends, blind before, can see again.

But the gun goes off one time anyway — and the stray bullet penetrates the glass, finally breaking it, but ironically hitting Prairie in the process.

Did Prairie’s story really happen? Is she really someone who had an otherworldly experience, and is now in touch with some higher power — and can inspire that same power in others?

Ultimately, it is up to the viewer to decide (or perhaps all will be answered in season two).

My personal opinion is that, no, her story isn’t “real.” Homer and the other prisoners don’t exist. The magical dance is just a dance.

(But if none of the story is real, how does Prairie regain her sight? Since it’s not entirely clear why she lost her sight in the first place, perhaps it was all psychosomatic.)

So in a sense, yes, I’ll concede there’s a certain ambiguity to this story. And those folks who regularly read my blog know that I absolutely prefer a story with some sense of resolution. If it’s ambiguous, there needs to be a reason for it. If there isn’t, it often seems like lazy storytelling — like the writer didn’t quite know how to end the story, or simply isn’t that interested in matters of plot.

I don’t think that’s what was going on here at all. I think the show was very very clear about the story they were telling.

They were just telling a story where the resolution doesn’t depend on what literally happened. In fact, that’s the whole point of the story: it doesn’t matter if Prairie’s story is “real” or not.

All the characters in this story are alone and disconnected: by Plexiglas windows, by vacant lots, by classrooms, by country borders, by conventional gender, by the lies husbands and wives tell each other, and even by the line between life and death.

One woman, Prairie, has an answer for this disconnectedness: this crazy story she tells her friends. In the moment when the shooter is about to shoot the school, when they all take a leap of faith and believe in Prairie even though it’s crazy, they are all connected in a way they’ve never been connected with anyone before.

And it works! The shooter is distracted and captured. Lives are saved.

Did Prairie’s story literally happen? Did their dance literally perform some kind of magic?

Who cares?! The four friends were connected in a real way, and they were alive in a way they’d never been before. That’s all that matters. They were blind, but they made a leap of faith, and now they can finally see this truth.

Prairie really has learned the fundamental truth of the universe, of being alive: that connection is the most important thing. It is all that matters. And it’s always possible, no matter how disconnected things seem, if there’s another human being with you, and if you truly believe connection is possible.

This truth has nothing to do with religion, or magic, or a higher power of any kind. It is true whether it’s literally “true” or not.

But having discovered the universe’s great secret, Prairie has become “divine” — even if that’s only metaphorical. And a divine being can’t live long in this imperfect world. So, like Jesus and a zillion other Christ figures, she is sacrificed for her truth. (Or does she die? Remember, such figures sometimes resurrect as well.)

Obviously, a lot of people found this ending unsatisfying, but I found all this to be breathtakingly bold storytelling that successfully communicated an incredibly complex idea.

I can’t begrudge anyone their reaction: if they were frustrated, they were frustrated. And I do get how it might be irritating for some people to be told a “true” a story, and then be told, “It isn’t true, but it doesn’t matter if it’s true!”

That said, I do reject the idea that the creators didn’t know exactly what they were doing. I truly don’t believe this was another Lost or Twin Peaks, with their ultimately muddled storytelling — where it was all so vague that people could project any “answer” they wanted.

No, I’m in awe of the writing in The OA, and I look forward to seeing what the creators do next, whether it’s a second season, or something else entirely.

P.S. I’ve written two stories with unusual endings myself. Check out Three Truths and a Lie and Grand Humble.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

December 26, 2016

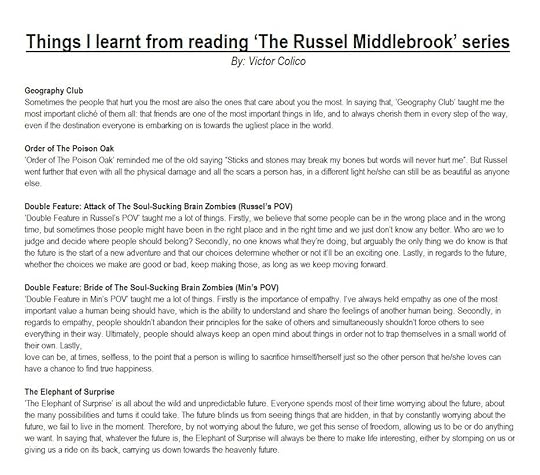

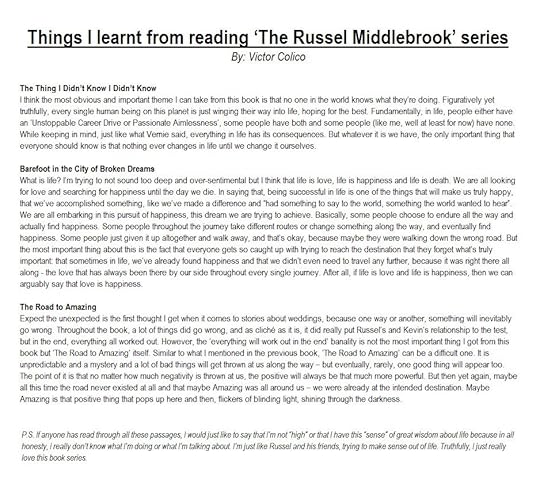

One Reader’s Take on the Russel Middlebrook Books…

A reader recently Tweeted his thoughts on all the Russel Middlebrook books so far. Authors are never supposed to say what a book “means” — we’re supposed to leave it up to the reader to decide.

(But I still think he’s right on!)

Click on each for a more legible size:

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

December 14, 2016

GREMLINS: My Movie Review

Michael and I watched GREMLINS last night, because it’s supposedly a “holiday” movie.

Okay, this one’s probably going to get me into trouble, because I remember watching this as a kid back in 1984, and really hating it.

And, well, I still hated it. Honestly, everything about it seems sloppy and lazy. The Asian mystic is a racist trope, the three important cautionary lessons about mogwai are revealed in a vague voice-over to the Dad (who’s not even in the POV character), and 100% of the pre-gremlin jokes are cartoony and awful. Most of the supporting characters are incredibly broad and cliched (the bumbling inventor father, the bitchy Mrs. Deagle), and they don’t have anything in the way of character arcs, and don’t have anything to do with Billy or his story. For example, in a series of stupid scenes, Mrs. Deagle is set up as a bitchy antagonist, but there is absolutely no pay-off: later, she’s casually dispatched by the gremlins when she’s flung out into the snow, and never heard from again.

Me, watching this incredibly stupid movie.

Meanwhile, the biology of the gremlins…oh, Lord, don’t get me started. They reproduce asexually (and almost INSTANTLY) by getting WET, they’re killed by sunlight, they appear to speak English and have a full working knowledge of all pop culture (and most science) from birth. Their various “life stages” apparently hate each other. They can’t be fed after midnight? Midnight where? And why not?

This is, like, the worst world-building I’ve ever seen in my life. None of it makes any sense, or resembles “reality” in even the vaguest possible way.

As for Billy, his character is: he’s a cute, nice guy. His motivation is: he wants to kill the gremlins (and date Kate, who is as perfunctory a female lead as is cinematically possible). Nothing he does sets anything in motion, he makes absolutely no mistakes he has to redeem himself for, and it’s Gizmo, not him, who saves things in the end (though Billy does destroy the gremlins in the movie theater in literally the most hackneyed movie way possible: by turning on “gas” and, 20 seconds later, the whole theater explodes, killing every last gremlin except Stripe).

There’s a ton of convoluted backstory about Billy’s life (he works at a bank! his dad is a terrible inventor! Billy likes his dog! Billy has a friend who sells Christmas trees!), but none of it is in any way related to anything in the rest of the story, or is even, like, vaguely interesting.

And of course he doesn’t really change or learn anything, except maybe, “Be sure to listen to your dad when he brings home a crazy pet and lazily mumbles something about three important rules.”

This screenplay seems to like it was written by a stupid child. (It’s actually written by Chris Columbus, so I’m not far off.)

I’m watching all of this unfold, and occasionally relating it to Michael, driving him crazy. Finally, he says, “It’s not supposed to make sense! It’s just supposed to be stupid and fun with lots of scenes of gremlins doing crazy s**t.”

And yeah, I agree that the gremlin in the microwave is great.

The rest of it? I give up

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

December 7, 2016

Would You Rather Be a Bestselling Hack or a Critical Darling?

So Erik Hanberg and I have been discussing some pretty interesting topics on our podcast lately. Here are some of my favorites:

Would You Rather Be a Bestselling Hack or a Critical Darling?

Is “One Great Thing” the Secret to Artistic Success?

How Are Technology and Science Portrayed in Movies and TV?

Check em out!

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

December 5, 2016

Classic Christmas Specials Often Include Surprisingly Crappy Storytelling

So like most people, I love me some classic Christmas specials. And because I’m older, some of the specials are probably ones that kids today don’t watch anymore.

Every year I watch them anyway.

But the older I get, and the more I begin to understand this concept of “storytelling,” the more I see how these Christmas specials often contain incredibly crappy writing.

But the older I get, and the more I begin to understand this concept of “storytelling,” the more I see how these Christmas specials often contain incredibly crappy writing.

Take Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. I know everyone picks on this because of the sadistic way Santa acts, and what a terrible father Donner is (and also the incredible sexism and subtle racism).

This is all well-deserved. At the same time, it was 1964. This was the zeitgeist.

As a writer, what’s harder for me to ignore are the incredible plot contrivances. The Abominable Snowman is the main antagonist, and Rudolph is away from him for months. When he finally returns, it just happens to be at the exact moment when the Snowman is about to eat Clarice and his parents?

I know Woody Allen says that success is eighty percent just showing up, but this is ridiculous.

Thirty seconds later, it’s also the exact moment when Hermy and Yukon Cornelius show up again to help Rudolph?

And how does Rudolph defeat the Snowman? Rudolph actually has nothing to do with it: Hermy pretends to be a pig (!!), Cornelius drops a rock on him (!!!), and then Hermy the dentist somehow removes all his teeth (!!!!). When Cornelius ends up falling off a cliff in the process (and doesn’t die), that’s all explained with the line, “Bumbles bounce!”

In the end, Rudolph is brave, true, but completely irrelevant to his own story. Even his subsequent big claim to fame — leading Santa’s reindeer through the fog — ends up being all Santa’s idea.

Then there’s the crappy world-building. Why does King Moonracer need Rudolph to tell Santa about the Island of Misfit Toys? The king can fly — he literally flies around the world every night!

Meanwhile, in The Year Without a Santa Claus, the “plot” hangs on getting Vixen released from the Dog Pound before he dies from heat exposure. But the only way Mrs. Claus can do this is to make it snow in the southern United States (???). To do that, she has to work out of compromise between Heat Miser, master of the sun, and his brother Cold Miser, the master of the snow.

Wouldn’t it be easier just to break Vixen out of the Dog Pound? Or claim him as his owner and, like, pay a fine? I mean, how hard could it be?

Wouldn’t it be easier just to break Vixen out of the Dog Pound? Or claim him as his owner and, like, pay a fine? I mean, how hard could it be?

And in the end, Mrs. Claus doesn’t really do anything anyway. She ultimately appeals to Heat Miser and Cold Miser’s mother, Mother Nature, and she sets everything right.

Assuming Mother Nature is a deity, it’s literally a deux ex machina ending!

Also, the special isn’t at all clear about whether Santa actually exists (and whether people, kids and adults alike, actually believe he exists). The newspapers all write about him as if he’s a real person, and there’s a montage at the end that implies that every kid in the world believes in him. But at the same time, some kids say that only “little kids” believe in Santa, and Santa himself says that he’s aware that no one believes in him anymore.

Now there’s some really, really imaginative stuff in both these specials — there’s a reason they’re classics — and there are definitely some catchy tunes. And yes, I know these are supposed to be stories for kids (as if that’s an excuse for bad writing!).

But in terms of sheer storytelling and basic world-building, some of this is clunky beyond belief.

So what’s the lesson for us writers?

It’s two things I often tell my writing students: True creativity and innovation, which these specials actually had in spades, will engender a hell of a lot of goodwill in your audience.

And if you get the emotional heart of your story truly right, viewers will forgive almost any plot mistake.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

November 17, 2016

In Seattle? Meet Me at the Holiday Bookfest, Saturday, November 19th!

So I’ll be signing books and meeting people this Saturday, November 19th, from 3-5 PM, at the Seattle7 Holiday Bookfest! It takes place at the Phinney Neighborhood Center, 6532 Phinney Ave. N. Seattle, 98103.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

September 1, 2016

Yes, BAREFOOT IN THE CITY OF BROKEN DREAMS is an Homage to SUNSET BOULEVARD. Here’s How:

Sunset Boulevard is the most famous (and probably the best) movie about Hollywood ever made. So now it’s virtually impossible to write about Hollywood without at least being aware of the movie, either to pay homage or to avoid looking like you’re ripping it off.

Sunset Boulevard is the most famous (and probably the best) movie about Hollywood ever made. So now it’s virtually impossible to write about Hollywood without at least being aware of the movie, either to pay homage or to avoid looking like you’re ripping it off.

In the case of my 2015 book Barefoot in the City of Broken Dreams, I’m definitely paying homage. It’s not necessary to have seen the movie for the book to make sense, but if you have seen the movie, here are a few of the Easter eggs:

Spoiler alert! Don’t read this unless you have read the book!

(1) The book begins and ends with Russel floating “dead,” facedown in a pool.

(2) Joe Gillis’ apartment in Sunset Boulevard is 1851 North Ivar Street. Russel and Kevin live right next door (in a non-existent address).

(3) Like Norma Desmond, Issac Brander lives just off of Sunset Boulevard, in an old house with an unmaintained yard.

(4) Like Norma, Isaac has an enigmatic assistant, Lewis, who isn’t exactly what he seems, and who ends up ultimately telling Russel the truth about Isaac.

(5) Some of the objects in Isaac’s office include a stuffed monkey (like Norma’s dead monkey, which opens the movie) and a package of Melachrino cigarettes (Norma’s brand).

(6) Like Norma, Isaac lives in the past and dreams of being important again. Their friends are all from a past era too: Norma knows Buster Keaton and H.P. Warner, and Isaac knows Sally Field and Sean Connery.

(6) Like Norma, Isaac lives in the past and dreams of being important again. Their friends are all from a past era too: Norma knows Buster Keaton and H.P. Warner, and Isaac knows Sally Field and Sean Connery.

(7) The “ghost” of the dead screenwriter in Russel’s apartment is named Cole Gordon. Gordon Cole is the man from Paramount who calls Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard.

(8) Russel talks a lot about all the movies filmed in and about Los Angeles, but he never mentions Sunset Boulevard, the most famous Hollywood movie of all. There are two ways to look at this: Subconsciously, Russel doesn’t want to accept that he’s living this movie (which ends in tragedy, and Russel would know that). Or perhaps the movie doesn’t exist in the Russel Middlebrook universe.

(9) Norma gives Joe Gillis valuable cufflinks; Isaac gives Russel a valuable edition of The Glass Menagerie. After being seduced by Norma and Isaac’s promises of fortune, both Joe and Russel prove that they’re leaving the world of illusion by giving those items back again (and by doing so, they invoke their patron’s wrath).

(10) When Russel meets Isaac, he imagines a tango, which is Norma’s favorite music. Later, during the dinner party, a tango plays.

(11) At Norma Desmond’s New Year’s Eve party, Joe Gillis is surprised that he’s the only guest. Likewise, Russel and Kevin are surprised to be the only guests at Isaac’s dinner party. (Fewer people to disturb Norma and Isaac’s delusions.)

(12) Like Norma, Isaac moves in and out of a world of fantasy. But also like Norma, Isaac is (hopefully) more than a pathetic stereotype — there is much to admire about him — and he doesn’t go outright crazy until Russel finally accepts reality, and forces Isaac to see reality too.

Despite all this homage (and probably more stuff that I’ve since forgotten about), Russel isn’t Joe Gillis, and Hollywood and the world have changed a lot since 1950. As a result, my story ends up going in some very different directions, and the ending is different too. In fact, here is the final line of Barefoot in the City of Broken Dreams:

I was thinking about Kevin, and all that had happened to me in Los Angeles, and I’m totally realizing the irony even as I’m telling you this, but I can honestly say that in my entire life, I had never felt so fucking alive.

In other words, Joe Gillis dies, but Russel Middlebrook’s experience in Hollywood ends up making him feel more alive than he’s ever felt. This is by design: Sunset Boulevard is a tragedy, so I was determined to confound reader expectations and give my story a happy ending.

P.S. Even more interesting? Much of the story of Barefoot in the City of Broken Dreams is based on my actual life; almost everything that happened to Russel really happened to me, when I was in my 20s. But like Russel, I couldn’t see, or accept, that I was living the Sunset Boulevard story until it was all over.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

August 23, 2016

About the Ending of GRAND & HUMBLE…

So I recently released a revised edition of an older book of mine, Grand & Humble, which tells the story of the most popular teenager in a high school, and the least popular kid, and the mystery of how the two boys are linked.

So I recently released a revised edition of an older book of mine, Grand & Humble, which tells the story of the most popular teenager in a high school, and the least popular kid, and the mystery of how the two boys are linked.

(It’s currently available for FREE in all e-platforms.)

It’s one of my personal favorites of all my books, with a “twist” ending that I’m really proud of.

That said, I’m aware that some people find the ending confusing. That’s led directly to a few one and two-star reviews on Amazon (along with some raves, natch).

That’s okay. Everyone’s entitled to their opinion. And I agree that to understand the ending, you have to understand a pretty complicated idea. The ending is, and was always intended to be, a real mind-bender. How exactly are these two characters related?

For the record, if you’re confused, here’s the answer. Spoiler alert!

Harlan and Manny are the same person, but in different timelines. In Manny’s timeline, his birth-parents were killed at the corner of Grand & Humble. In Harlan’s timeline, his parents avoided the accident and survived. Harlan is who Manny might have been, and vice-versa.

Over the course of the novel, Harlan and Manny’s paths almost seem to cross again and again. But of course their paths never do actually meet, because they can’t. They exist in separate time-lines, after all. Meanwhile, their paths do cross those of their respective best friends. That’s because those characters exist in both timelines (albeit as slightly different versions of themselves.)

Like I said, it’s a complicated idea! I admit that I, the author, use a lot of misdirection along the way, trying to keep the final reveal a secret until the very end. The entire “separated twin brothers” subplot is a red herring. But that’s what the author of every mystery does, and this book is a classic puzzle box mystery. Of course, once the answer is revealed, it should all make sense in retrospect.

For many readers, it does. But some are having a hard time making that final leap.

Am I disappointed that some people are confused? In a way, yes. I’ve said many times that the whole point of writing is communication, and the whole point of communication is to be clear. To be understood.

Also, I don’t ever want anyone to feel stupid or confused by something I’ve written.

That said, it was difficult to simply reveal the truth, since neither of the main characters is aware of the other; they solve the problems of their own lives, but neither of them solves the overall mystery of the novel. That’s up to the reader, who has to be the one to put all the pieces together and figure it out. At the end of the second to last chapter, I did try to spell it out as clearly as possible:

Manny didn’t want to dwell on the past, at least not right now. But there was one more thing he wanted to know. “What were their names, my parents?”

“Victoria and Richard Chesterton,” his dad said. “They used to call you by your first name, not Manny. Your middle name. It’s a family name, but I always thought it sounded pretentious. Which means if they hadn’t died in that accident at Grand and Humble, right now everyone would probably call you—”

“Harlan Chesterson,” Manny said.

If I had to do it again, would I do write the book differently? Well, it always really sucks to get one and two-star reviews on Amazon or Goodreads. But plenty of people “get it” as well.

And let’s face it, the whole point of Grand & Humble is to get the reader to question something very fundamental: these two characters seem completely different, virtually opposites, but they’re not. In fact, if not for the events at the corner of Grand and Humble, they would be exactly the same.

Could this be true for all of us? In America especially, many of us talk like we are all in complete control of our lives, that we are the sum result of the choices we’ve made. And in a way, that’s kind of true. But it’s also true that we are the result of some forces beyond our control. Most of us are smart and humble enough to admit that certain events in our lives, certain situations, are so profound that if they hadn’t happened, we’d be someone pretty different.

This is what I’m exploring in the novel, in addition to writing what I hope is an engrossing, entertaining puzzle box thriller.

In the end, I’m pretty happy with this latest edition of the book, even as I recognize that not every book is for every reader.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle