Robert I. Sutton's Blog, page 18

January 24, 2011

My First Time Attending the World Economic Forum at Davos

I am in the final throes of getting ready for the World Economic Forum, which takes place this week in Switzerland. I have never attended before and some of the famous people on the list are rather daunting. There will be sessions involving world leaders like David Cameron from the UK, Angela Merkel of Germany, Bill Clinton from the U.S., lots of CEOs including Google's Larry Page to Heinken's Jean-François van Boxmeer, and a session by "miracle on the Hudson" pilot Sulley Sullenberg. You can read about it here in the The New York Times, which has a wonderfully cynical opening paragraph.

I am among the many academics invited and will be participating in three sessions. First, I am moderating a session on design thinking and business, which should be interesting as it is becoming ingrained in the positions and practices of so many organizations now. Second, I am participating in a session on what leaders of the present can learn from leaders of the past. Third, I give a talk on "the no jerk rule." The WEF is sufficiently respectable that the organizers thought it was best to refrain from using the world "asshole" in the title. But I plan to use it a few times in the talk, although perhaps fewer times than usual. In addition to the sessions I am part of, I am going to focus on learning about scaling, my current primary project, as several sessions focus on the topic and there will be a lot of people there who have a lot of experience with this challenge.

The place is just buzzing with interesting people and sessions, but I have been warned by the people who run the event and by experienced participants like IDEO CEO Tim Brown to pace myself as it can get overwhelming. They also have warned me to bring warm clothes and good snow boots as it is a ski resort.

I will do some tweeting and blogging. I don't know quite how much, as I expect I will be busy and distracted. But let me know if there is anything you are especially interested in hearing about, and I will try to address it.

January 18, 2011

Meetings and Bosshole Behavior: A Classic Case

One of the themes in Good Boss, Bad Boss, as well as some of my past academic research (see this old chapter on meetings as status contests), is that bosses and other participants use meetings to establish and retain prestige and power. This isn't always dysfunctional; for example, when I studied brainstorming at IDEO, designers gained prestige in the culture by following the brainstorming rules, especially by generating lots of ideas and building on the ideas of others. And when they built a cool prototype in a brainstorm, their colleagues were impressed. The IDEO status contest was remarkably functional because it wasn't an I win-you lose game; everyone who brainstormed well was seen as cool and constructive. In addition, the status game rewarded people who performed IDEO's core work well.

Unfortunately, too many people, especially power-hungry and clueless bosses, use meetings to display and reinforce their "coercive power" over others in ways that undermine both the performance and the dignity of their followers. As I've shown, bosses often don't realize how destructive they are because power often causes people to be more focused on their own needs, less focused on the needs and actions of others,and to act like "the rules don't apply to me."

I was reminded of the dangers of bosshole behavior in meetings by this troubling but instructive note I received the other day. It is a classic case. Note this is the exact text sent me by this unnamed reader, except that I have changed the bosshole's name to Ralph to protect the innocent and the guilty:

I wanted to pass on to you a trick my most recent crappy boss used to use in meetings.

The manager I am thinking of is particularly passive-aggressive and also really arrogant at the same time. He was notorious for sending these ridiculous emails that were so long that no one would read them. (He's also an engineer in every sense of that word) This was at a technology company and we used to start our Mondays off with a business/technical discussion. These meetings initially took an hour but soon turned into 2 and would regularly go 3 and sometimes 4 hours. It was mostly 'Ralph' talking expansively about the issues at hand, about those mother-scratchers in the head office and why we shouldn't take our challenges back to them (Really? Don't want to solve anything? Really?). It was just unbelievable, we rarely got anything useful accomplished.

His favorite tricks, though, were pretty much verbatim from your book. He'd arrive 10 – 20 minutes later for almost every meeting and then kill them once in a while. He added an interesting twist to this too. Every so often, if we knew we had work items to cover, we'd forget about the last time and start the meeting without him. Then he'd arrive an hour late without apology, ask what we covered and then make us start the whole meeting again. After all, it couldn't be a real meeting without 'Ralph'. And we needed to learn from his vast wealth of experience, didn't we?

A few questions:

Have you ever seen behavior like this in other places?

If you are a boss, how do you stop yourself from wielding power in dysfunctional ways, and instead, create a functional status contest?

If you boss acts like an overbearing jerk during meetings, how can you fight back?

January 17, 2011

A Great Pixar Story: Alvy Ray Smith and Ed Catmull Serve as Human Shields

Note: I originally posted this at HBR.org. You can see the original and the 13 comments here and can see all my posts at HBR here. I will continue to devote the lion's share of my blogging effort to Work Matters, but plan to post at HBR a couple times a month.

Pixar is one of my favorite companies on the planet. I love its films, its creative and constructive people (The Incredibles director Brad Bird is among the most intriguing people I've ever interviewed), and its relentless drive toward excellence. There's a pride that permeates that place, along with a nagging worry that, if they don't remain vigilant, mediocrity will infect their work. So I was thrilled to be invited to give a couple of talks about Good Boss, Bad Boss at Pixar last Fall. After the first one, Pixar veteran Craig Good (who has been there at least 25 years — I think he said 28 years), came up and told me an astounding story.

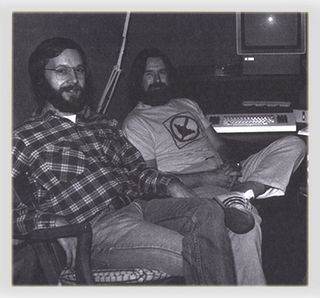

The story occurred to Craig because he'd just heard me claim that the best bosses serve as human shields, protecting their people from intrusions, distractions, idiocy from on high, and anything else that undermines their performance or well-being. For him, that brought to mind the year 1985, when the precursor to Pixar, known as the Computer Division of Lucasfilm, was under financial pressure because founder George Lucas (of Star Wars fame) had little faith in the economics of computer animated films. Much of this pressure came down on the heads of the Division's leaders, Ed Catmull (the dreamer who imagined Pixar long before it produced hit films, and the shaper of its culture) and Alvy Ray Smith (the inventor responsible for, among many other things, the Xerox PARC technology that made the rendering of computer animated films possible). The picture to the left shows Ed and Alvy around that period.

Lucas had brought in a guy named Doug Norby as President to bring some discipline to Lucasfilm, and as part of his efforts, Norby was pressing Catmull and Smith to do some fairly deep layoffs. The two couldn't bring themselves to do it. Instead, Catmull tried to make a financial case for keeping his group intact, arguing that layoffs would only reduce the value of a unit that Lucasfilm could profitably sell. (I am relating this story with Craig's permission, and he double-checked its accuracy with Catmull.) But Norby was unmoved. As Craig tells it: "He was pestering Ed and Alvy for a list of names from the Computer Division to lay off, and Ed and Alvy kept blowing him off. Finally came the order: You will be in my office tomorrow morning at 9:00 with a list of names."

So what did these two bosses do? "They showed up in his office at 9:00 and plunked down a list," Craig told me. "It had two names on it: Ed Catmull and Alvy Ray Smith."

As Craig was telling me that story, you could hear the admiration in his voice and his pride in working for a company where managers would put their own jobs on the line for the good of their teams. "We all kept our jobs," he marveled. "Even me, the low man on the totem pole. When word got out, we employees pooled our money to send Ed, Alvy, and their wives on a thank-you night on the town."

Certainly such extreme staff protection is rare and sometimes it might not even be wise. I can't say that every proposed layoff is immoral or unnecessary. But consider the coda: a few months after this incident, Pixar was sold to a guy named Steve Jobs for 5 million bucks and, as they say, the rest is history. And some 25 years later, that brave shielding act still drives and inspires people at Pixar.

P.S. I want to thank Pixar's Craig Good, Elyse Klaidman, and Ed Catmull for telling me this story and letting me use it. If you want to learn more about Pixar's astounding history, I suggest reading David Price's The Pixar Touch. It is well researched and a delight to read. While you're at it, check out Alvy Ray Smith's site and Dealers of Lightning if you want to learn about the impact this quirky genius has had on computer animation and other technical marvels.

January 5, 2011

Team Guidelines From A New Boss: How Can He Make Sure People Live Them?

I got a fascinating note from an employee of a big company about the "team norms" that were articulated by his new boss. I think they are great, but have a crucial question about them. Here they are:

I. Show respect

Support one another...don't blind-side one another in public.

Provide one another with a safe place...honor confidentiality.

Show up to meetings on time...and if you're running late, call.

Maintain professionalism...especially with clients / learners.

II. Be transparent

No hidden agendas

Get to the point...don't beat around the bush.

III. Stay positive

Celebrate successes

Have fun

Here is my question. Talk is not a substitute for action. Guidelines like these are great when they are drive and reflect behavior, but when they are consistently violated, they are worse than having no guidelines at all because the stench of hypocrisy fills the air. As such, what advice do you have for this boss to make sure that his team actually lives these norms?

My first thought was that he should focus on what happens when team members -- or himself -- violate the norms. After all, in any human group, people will break rules. In healthy groups, bosses call out others (and themselves) when transgressions occur, but do it in ways that builds rather than destroys safety and trust. It's noteasy to do, but I;'ve seen great bosses like IDEO's David Kelley do it in masterful ways.

That's my first thought. I would love to hear others.

P.S. A big thanks to the unnamed employee for sending these norms to me.

January 4, 2011

Good Boss, Bad Boss: USA Today and The McKinsey Quarterly

Over the break, a bit more news came out after I wrote posts on kudos for Good Boss, Bad Boss and the popularity of my list of 12 Things Good Boss Believe over at HBR.Org.

Last week, USA Today published a pair intertwined stories on workplace bullying, both of which drew on a long interview they did with me (and interviews with a host of other folks too, like Babson's Tom Davenport). The main story was called Bullying By the Boss is Common But Hard to Fix. I think the best part of this story (which, alas, opens with a story about Hooters from the TV show Undercover Boss) is the thoughtful list of why companies fail to take action compiled by journalist Laura Petrecca -- it includes impediments including: victims keep quiet, intervention can take time (this is one reason assholes especially get away with their dirty work when teams and companies are under time pressure), discipline can be subjective, legal recourse can be unclear (e.g., it is still unclear in most states if it is unlawful to be an equal opportunity asshole), and savvy bosses learn to work the system (as I said in the article " "They kiss up and kick down."

I also thought the second story, a sidebar on Survival Strategies for Workers Whose Bosses are Bullies was useful, and a nice complement to my list of Tips for Surviving and Asshole Infested Workplace. Here is the sidebar:

Bosses often get a bad rap — mainly because they are just that: the boss.

These are the folks who scrutinize vacation day requests, ask for client reports to be revised and tell employees the company decided against 2010 raises. So naturally they will be closely scrutinized — and criticized — by workers, simply because they have such a large impact on their life.

"Bosses pack a wallop, especially on their direct reports," says Robert Sutton, author of Good Boss, Bad Boss.

However, there are many supportive, compassionate managers out there, Sutton says. "Most of us think our bosses are OK."

But for the folks toiling under a lousy manager, the daily stress can be severe. Some ways to deal with a bad boss:

•Have a heart-to-heart. "Perhaps your boss is one of those people who aren't aware of how they come across," Sutton says. It could be worth it to have a "gentle confrontation" with the manager in hopes of evoking a behavior change.

•Get help. "It's like a bully on the playground," says Tom Davenport, co-author of Manager Redefined. "At some point you have to go tell the teacher."

Employees should keep a detailed diary of a boss' bad behaviors and then bring up those specific instances when lodging a complaint.

"Don't talk about the way you feel. Don't say 'I'm hurt,' " says workplace consultant Catherine Mattice. Instead give very specific examples of how the boss crossed the line.

•Zone out. With some effort — be it meditation, therapy or another method — some folks are able to leave their work troubles at the office. "Learn the fine art of emotional detachment," Sutton says. "Try not to let it touch your soul."

•Update the résumé. "Start planning your escape," Sutton says. Sure, the economy may not be the best for job seekers, but those who put feelers out now will have a head start when the hiring freeze thaws.

In addition, I also learned that the McKinsey Quarterly piece based on Good Boss, Bad Boss, "Why Good Bosses Tune In To Their People" was among their 10 most read pieces in 2010. You can see the complete list and access is free, although you do need to register. My favorite on the McKinsey list is "The Case for Behavioral Strategy" by Dan Lavallo and Oliver Sibony. It makes a compelling, evidence-based, case about the damage done by executives who make strategic decisions without taking their own cognitive biases into account and shows how executives can make superior decisions (and thus help their companies and keep their jobs) by taking steps to dampen and eliminate these universal human imperfections.

Enough looking back on 2010, its time to move forward into 2011!

January 3, 2011

My Main Focus for 2011: Scaling Good Behavior

Now that the launch of Good Boss, Bad Boss is done, along with a host of chores related to The No Asshole Rule paperback and the Asian Leadership edited volume, I am turning to future projects. I'm working on two projects, both of which are in the early stages.

The first follows from my focus on the humanity the workplace. I would tell you more, but it is so ill-formed that I change my mind about the exact focus a couple times a week. The only thing I can tell you for sure is it won't be a sequel to either Good Boss, Bad Boss or The No Asshole Rule.

The second is a project that fits with my work on innovation and organizational change. My Stanford colleague Huggy Rao and I have been talking about and doing case studies on "scaling" for a few years now -- the challenge of spreading and sustaining actions and mindsets across networks of people. This will be my primary focus for the year and I hope we can make serious progress in 2011 on a book that digs into the topic. It feels like we are making good progress, but every book has a life of its own, and who knows how fast or how well this one will unfold.

The new HBR provides summaries of projects that a host of of business and management leaders will be taking on in 2011. You can find this and the other 23 projects here at HBR. I especially liked Tim Brown's on Granting Permission to Innovate and J. Richard Hackman's on Managing Ever-Shifting Teams.

Here is my "agenda" piece, repeated completely, as I would love any comments, suggestions, examples, or other ideas you have. This project is just starting to take shape and Huggy and I need all the help we get!

My Stanford Business School colleague Hayagreeva Rao and I are absorbed by why behavior spreads—within and between organizations, across networks of people, and in the marketplace. We've been reviewing academic research and theory on everything from the psychology of influence to social movements to how and why insects and fish swarm.

We are also doing case studies. We're documenting Mozilla's methods for spreading Firefox (its open-source web browser); the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's "100,000 Lives" campaign (an apparently successful effort to eliminate 100,000 preventable deaths in U.S. hospitals); the spread of microbrewing in the United States; an organizational change and efficiency movement within Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (now part of Pfizer); and the scaling of employee engagement at JetBlue Airways. And we're examining case studies by others, including the failure of the Segway to scale and the challenges faced by Starbucks as a result of scaling too fast and too far.

Our goal is to write a book in 2011 that provides useful principles for managers, entrepreneurs, and anyone else who wants to scale constructive behavior. Because we are in the messy middle, I can't tell how the story will end. But we believe we're making progress, and we're excited about a few lines of thought.

The first is the link between beliefs and behavior. A truism of organizational change is that if you change people's minds, their behavior will follow. Psychological research on attitude change shows this is a half-truth (albeit a useful one); there is a lot of evidence that if you get people to change their actions, their hearts and minds will follow.

The second theme is "hot emotions and cool solutions." As Rao shows in his research on social movements, a hallmark of ideas that scale is that leaders first create "hot" emotions to fire up attention, motivation, and often righteous anger. Then they provide "cool," rational solutions for people to implement. In the 100,000 Lives campaign, for example, hot emotions were stirred up by a heart-wrenching speech at the kickoff conference. The patient-safety activist Sorrel King described how her 18-month-old daughter, Josie, had died at Johns Hopkins Hospital as the result of a series of preventable medical errors. Her speech set the stage for IHI staffers to press hospitals to implement six sets of simple, evidence-based practices that would prevent deaths.

The third is what we call the ergonomics of scaling—the notion that when behaviors scale, it is partly because they've been made easy, with the bother of engaging in them removed. In developing Firefox in the early days, Mozilla's 15 or so employees were able to compete against monstrous Microsoft (and produce a browser with fewer bugs than Internet Explorer) by dividing up the chores and using a technology that made it easy for more than 10,000 emotionally committed volunteers to do "bug catching" in the code. Mozilla now has more than 500 employees, but it is still minuscule compared with Microsoft, and those bug catchers are still hard at work every night.

Again, I would love your ideas.

December 28, 2010

"12 Things Good Bosses Believe" is the Most Popular Post at HBR in 2010

I got a note from Julia Kirby at HBR a few days back that my list of "12 Things Good Bosses Believe" has been the most popular post at HBR.Org in 2010 -- a list based on ideas from Good Boss, Bad Boss.

Here is Jimmy Guterman's list of the Top 10 posts at HBR in 2010:

12 Things Good Bosses Believe

Robert Sutton, author of Good Boss, Bad Boss, ponders what makes some bosses great.

Six Keys to Being Excellent at Anything

Tony Schwartz of the Energy Project reports on what he's learned about top performance.

How (and Why) to Stop Multitasking

Peter Bregman learns how to do one thing at a time.

Why I Returned My iPad

Here, Bregman finds a novel way to treat a device that's "too good."

The Best Cover Letter I Ever Received

Although David Silverman published this with us in 2009, it remained extremely timely this year.

How to Give Your Boss Feedback

Amy Gallo reports on the best ways to help your boss and improve your working relationship.

You've Made a Mistake. Now What?

We all screw up at work. Gallo explains what to do next.

Define Your Personal Leadership Brand

Norm Smallwood of the RBL Group gives tips on how to convey your identity and distinctiveness as a leader.

Why Companies Should Insist that Employees Take Naps

Tony Schwartz makes the case for naps as competitive advantage.

Six Social Media Trends for 2011

David Armano of Edelman Digital ends the year by predicting our social media future.

I am pleased and also somewhat embarrassed because, well, I haven't quite finished the post yet! I promised to write detailed posts on all 12 ideas listed, but I only made it through the first 10. I will finish in the next couple weeks, or at least I hope to, as life keeps happening while I make other plans (as that lovely old saying goes).

December 22, 2010

Good Boss, Bad Boss on Five "Best Business Book" Lists for 2010

Good Boss, Bad Boss has been selected as among the best business books of the year on five lists I've heard about. These are:

1. INC Magazine's list of "Best Books for Business Owners."

2. One of the Globe & Mail's Top 10 Ten Business Reads of 2010.

3. One of the four "best of the rest" selections by 1-800-CEO-Read in the leadership category, behind the winner Bury My Heart at Conference Room B. (I love that title, just brilliant).

4. The New York Post's Round-Up of Notable Career Books for 2010.

5. The Strategy & Business list of the four best Best Business Books in the leadership category. See the excerpt below from, Walter Kiechel III's story here, which I found to be generally fun, thoughtful, and well-written (you have to register, but it is free). Here is Walter's rollicking review:

Better Bossiness

Finally, for a head-clearing blast of sauciness, pick up a copy of Robert I. Sutton's Good Boss, Bad Boss: How to Be the Best...and Learn from the Worst. In a year when too many leadership books combined solemn with vapid, Sutton's decision to focus on the figure of "the boss" comes across as thoroughly refreshing. Even after decades of study, we may not agree on what constitutes a leader or all the proper functions of a manager, but everybody knows who the boss is.

If it's you, however long you've been at it, you can probably benefit from Sutton's breezy tour of the wisdom he has distilled from scholarly studies, his own experience, and the thousands of responses he received to his last book, The No Asshole Rule: Building a Civilized Workplace and Surviving One That Isn't (Business Plus, 2007). To say that Sutton, a Stanford professor, wears his learning lightly is to understate the case. At times he wears it like a vaudeville comedian's gonzo-striped blazer with accompanying plastic boutonniere shooting water. This is a weirdly merry book, perfect for a down year — but not an unserious book.

Consider, for example, Sutton on the imperative to take control. Yes, you as a leader have to, he counsels, in the sense that "you have to convince people that your words and deeds pack a punch." And he offers up a series of fairly familiar gambits to that end: "Talk more than others — but not too much." "Interrupt people occasionally — and don't let them interrupt you much." "Try a little flash of anger now and then." What redeems this from being mere Machiavellian gamesmanship is Sutton's admission that any control you pretend to is probably largely an illusion — there's a lot of play-acting in any executive role, he wants us to know. He makes the case that pushing too hard in the wrong way is a lot more dangerous than not pushing hard enough. Given the danger of the "toxic tandem" — your people are always scrutinizing you, at the same time that power invites you to become self-absorbed — leaders are always on the edge of becoming bad bosses, or even worse, bossholes. So he also advises you to blame yourself for the big mistakes, serves you up a seven-part recipe for an effective executive apology, reminds you to ask the troops what they need, and finishes with the injunction, "Give away some power or status, but make sure everyone knows it was your choice."

Another chapter title captures the overall aspiration Sutton advocates: "Strive to Be Wise." His is a street-smart, been-around-the-block-but-still-a-happy-warrior brand of wisdom, rooted in a boss's understanding of himself or herself coupled with an appreciation that bosses have to take action and make decisions, including doing lots of what Sutton labels "dirty work." As a boss "it is your job to issue reprimands, fire people, deny budget requests, transfer employees to jobs they don't want, and implement mergers, layoffs, and shutdowns." Wise bosses understand that although they may not be able to avoid such unpleasantness, how they go about the dirty work makes an enormous difference. Empathy and compassion are good places to start, says Sutton. Layer on constant communication with the affected, including feedback from them you really listen to, however painful it is. Finally, you'll probably need to cultivate a measure of emotional detachment, beginning with forgiveness for the people who lash out at you. And maybe reserving some forgiveness for yourself.

Indeed, Good Boss, Bad Boss is in its entirety a page-by-page guide to better bossly self-awareness. The variety of sources cited can be dizzying. On one page you may get a summary of two academic studies, a quote from Dodgers coach Tommy Lasorda, a recollection of Sutton's parents, and three examples of bad bosses sent in to Sutton's website. (At times, the book seems almost crowdsourced and puts one in mind of Charlene Li on the power of social technology to expose behavior.) What gives all this consistency and makes for an enjoyable read is Sutton's voice throughout — at times yammering, on rare occasions bordering on the bumptious, but in general so "can you believe this?" ready to laugh at the author's own pratfalls, and so eager to help, that the net effect is sneakily endearing. Rather a comfort in a low, mean year.

That guy can write, huh?

As a closing comment, I am tickled with the recognition this book received and certainly that it appeared on The New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestseller lists. But perhaps the most important thing to me is that, when I talk to bosses of all levels -- from management trainees, to project managers, to chefs, to film directors and producers, to CEOs and top management teams, the core themes in the book sometimes surprise them a bit, but nh early always strike them as pertinent and central to the challenges they face. I have talked to some 50 different groups about the ideas in Good Boss, Bad Boss since June and -- although I enjoy talking about all my stuff with engaged audiences -- there is something about this book that engages people more deeply than any book I've written since Jeff Pfeffer and I came out with The Knowing-Doing Gap in 1999.

Finally, I want to thank all of you who read my blog for your support and encouragement. Your suggestions, stories, and disagreements (with me me and each other) played a huge role in shaping the content and tone of Good Boss, Bad Boss, and I am most grateful for all the ways you helped.

December 19, 2010

New Study: When NBA Players Touch Teammates More, They and Their Teams Play Better

I've written here before about research on the power of "non-sexual touching," notably evidence that when waitresses touch both male and female customers on the arm or wrist, they tend to be rewarded with bigger tips. Plus I wrote about another study that shows when either women or men are touched lightly on the back by women, they tend to take bigger financial risks. That second study showed that touching by men had no effect. Well, there is a new study that shows the power of nonsexual touch among male professional basketball players. You can read the pre-publication version here.

It is called : "Tactile Communication, Cooperation, and Performance: An Ethological Study of the NBA" and was published by Michael W. Kraus, Cassy Huang, and Dacher Keltner in a well-respected peer reviewed journal called Emotion earlier this year (Volume 10, pages 745-749).

In brief, here is how they set-up the paper; these are opening two paragraphs:

Some nonhuman primates spend upward of 20% of their waking hours grooming, a behavior primates rely upon to reconcile following conflict, to reward cooperative acts of food sharing, to maintain close proximity with caretakers, and to soothe (de Waal, 1989; Harlow, 1958). In humans, touch may be even more vital to trust, cooperation, and group functioning. Touch is the most highly developed sense at birth, and preceded language in hominid evolution (Burgoon, Buller, & Woodall, 1996). With brief, 1-second touches to the forearm, strangers can communicate prosocial emotions essential to cooperation within groups—gratitude, sympathy, and love—at rates of accuracy seven times as high as chance (Hertenstein, Keltner, App, Bulleit, & Jaskolka, 2006). Touch also promotes trust, a central component of

long-term cooperative bonds (Craig, Chen, Bandy, & Reiman, 2000; Sung et al., 2007; Williams & Bargh, 2008).

Guided by recent analyses of the social functions of touch (Hertenstein, 2002), we tested two hypotheses. First, we expected touch early in the season to predict both individual and team performance later on in the season. Second, we expected that touch would predict improved team performance through enhancing cooperative behaviors between teammates.

I love that. As I always tell doctoral students, and I emphasized during the years that I edited academic journals. A research paper is not a murder mystery. The reader should know what you are studying and why by the end of the second paragraph -- this is a nice example.

Kraus and his colleagues go onto explain their research method a bit later:

Coding of the tactile communication of 294 players from all 30 National Basketball Association (NBA) teams yielded the data to test our hypotheses. Each team's tactile behavior was coded during one game played within the first 2 months of the start of the 2008–2009 NBA regular season. Games were coded for physical touch and cooperation by two separate teams of coders.

They explain:

We focused our analysis on 12 distinct types of touch that occurred when two or more players were in the midst of celebrating a positive play that helped their team (e.g., making a shot). These celebratory touches included fist bumps, high fives, chest bumps, leaping shoulder bumps, chest punches, head slaps, head grabs, low fives, high tens, full hugs, half hugs, and team huddles.On average, a player touched other teammates (M = 1.80, SD = 2.05) for a little less than 2 seconds during the game, or about one tenth of a second for every minute played.

They also had coders rate the amount of cooperation by each player studied during that same early season game:

[t]he following behaviors were considered expressions of cooperation and trust: talking to teammates

during games, pointing or gesturing to one's teammates, passing the basketball to a teammate who is less closely defended by the opposing team, helping other teammates on defense, helping other teammates escape defensive pressure (e.g., setting screens), and any other behaviors displaying a reliance on one's teammates at the expense of one's individual performance. In contrast, the following behaviors were considered expressions of a lack of cooperation and trust: taking shots when one is closely defended by the opposing team, holding the basketball without passing to teammates, shooting the basketball excessively, and any other behavior displaying reliance primarily on one's self rather than on one's teammates.

Karaus and his coauthors then used these imperfect but intriguing measures of touching and cooperation to predict the subsequent performance of players and their teams later in the season; I won't go into all the analysis they did, but the authors did at least a decent job of ruling out alternative explanations for the link between touching and performance such as players salaries, early season performance, and expert's expectations about the prospects for team performance in 2008-2009. And they still got some rather amazing findings:

1. Players who touched their teammates more had higher "Win scores," defined as "a performance measure that accounts for the positive impact a player has on his team's success (rebounds, points, assists, blocks, steals) while also accounting for the amount of the team's possessions that player uses (turnovers, shot attempts). "

2. Teams where players touched teammates more also enjoyed significantly superior team performance than those where players touch teammates less (the authors used a more complicated measure of team performance than win-loss record, it took into account multiple factors like scoring efficiency and assists, and other measures, which correlated .84 with the number of wins that season.

3. The authors present further analyses suggesting that the increased cooperation among teams where players engage in more "fist bumps, high fives, chest bumps, leaping shoulder bumps, chest punches, head slaps, head grabs, low fives, high tens, full hugs, half hugs, and team huddles" explain why touching is linked to individual and team performance.

Now, to be clear, as the authors point out, this an imperfect study. They only looked at touching in one game for each team. So there is plenty to complain about if you want to picky. But I would add two reminders before we all get too critical. The first is that there is no reason I can see to expect that the weaknesses in this study would inflate the effects of touching; rather, quite the opposite. The second is that the touching and cooperation were coded by multiple independent coders who did not know the researchers' hypotheses or the patterns they were looking for, and there was very high agreement (over 80%) among them.

As the researchers emphasize. more research is needed, but this study at least suggests that it is worth doing. It is at least strong enough to increase rather decrease my confidence in the the touching-cooperation-team performance link. And the way it plays out in different settings might require some careful adjustments in research methods and employee behavior. For example, basketball is setting where touch is clearly more socially acceptable than in the offices that many of us work in. So if you and your sales or project team all of a sudden decide to start doing high-fives, group hugs, and chest bumps, it might backfire given local norms. Perhaps a more reasonable inference is that, given what is socially acceptable where you work, touching on the high side of the observed natural range just might help.

I would love to hear reader's comments ont his research, as it is quite intriguing to me.

P.S. No, this is not an invitation for you creepy guys out there to start grabbing your colleagues and followers in inappropriate ways that make them squirm and make you even more disgusting to be around!

December 17, 2010

What's Right About Being Wrong: A Sweet Little Essay by Larry Prusak

Those of who teach and study learning, innovation, design thinking, and creativity are constantly talking about how important it is accept and learn from failure. Diego has written great stuff on this, arguing that "failure sucks but instructs" and when I give speeches, I often half-joke that, if you want to skip reading most of my books, perhaps the best compact summary are my various snippets and blog posts on failure, and perhaps the best diagnostic question for determining if an organization learns well, a boss creates a climate of fear or not, is innovative, turns knowledge into action, and on and on, is "What happens when people make a mistake? " Do they balmestorm and stigmatize? Forgive and forget? Or do they forgive and remember (see this post at HBR), so they can learn, help others learn, be held accountable and -- if people keep making the same mistake -- be reformed, transferred, or perhaps fired.

Those of who teach and study learning, innovation, design thinking, and creativity are constantly talking about how important it is accept and learn from failure. Diego has written great stuff on this, arguing that "failure sucks but instructs" and when I give speeches, I often half-joke that, if you want to skip reading most of my books, perhaps the best compact summary are my various snippets and blog posts on failure, and perhaps the best diagnostic question for determining if an organization learns well, a boss creates a climate of fear or not, is innovative, turns knowledge into action, and on and on, is "What happens when people make a mistake? " Do they balmestorm and stigmatize? Forgive and forget? Or do they forgive and remember (see this post at HBR), so they can learn, help others learn, be held accountable and -- if people keep making the same mistake -- be reformed, transferred, or perhaps fired.

I just read the best piece on this perspective in a long time, a piece that the amazing Larry Prusak (who I would rather hear give a speech than any other management thinker, he can be magical) wrote for ASK Magazine called "What's Right About Being Wrong." Follow the link to read it all. Here are some quotes from this little gem that especially struck me:

It starts:

A number of years ago I was asked by some clients to come up with a rapid-fire indicator to determine whether a specific organization was really a "learning organization." Now, I have always believed that all organizations learn things in some ways, even if what they learn does not correspond well to reality or provide them with any useful new knowledge. After thinking about the request for a bit, though, I decided the best indicator would be to ask employees, "Can you make a mistake around here?"

Sounds familiar? Listen to the names he names in the next paragraph:

Why? Well, if you pay a substantial price for being wrong, you are rarely going to risk doing anything new and different because novel ideas and practices have a good chance of failing, at least at first. So you will stick with the tried and true, avoid mistakes, and learn very little. I think this condition is still endemic in most organizations, whatever they say about learning and encouraging innovative thinking. It is one of the strongest constraints I know of to innovation, as well as to learning anything at all from inevitable mistakes—one of the most powerful teachers there is. Some recent political memoirs by Tony Blair and George Bush also inadvertently communicate this same message by denying that any of their decisions were mistaken. If you think you have never made a mistake, there is no need to bother learning anything new.

The above paragraph really made me think. Indeed, just last night, I was having a drink with on my colleagues, and we were talking about the hallmarks of the good versus bad bosses we have had during our academic careers, and we realized that the good ones admit mistakes, tell everyone what they've learned, and push themselves and others forward in a new direction. The worst never admit they've made a mistake -- so they are seen as arrogant, unable to learn, and unable to teach and lead effectively. (See this related post on medical mistakes).

To continue, then Larry started talking about Alan Greenspan as the rare example of someone who admitted a mistake:

I can easily summon up the grave image of Alan Greenspan testifying before Congress last year on the causes of the financial crisis. What was so very startling was seeing him admit that he was wrong! It was such an unusual event that it made headlines around the world. But why should it be so rare and so startling? Greenspan had a hugely complex job, one where many critical variables are either poorly understood or not known at all. Nevertheless, neither he, nor any other federal director I have heard about, has ever said anything vaguely like what he did that day before our elected officials and the public.

It is quite an essay, and as always, Larry brings a new spin. I have not exactly had warm feelings toward Greenspan since the meltdown, but Larry does a nice job of showing us how rare his confession is among powerful people.

Finally, note that I am not arguing that people should go around apologizing constantly for every little thing, as I show in Good Boss, Bad Boss, there is a kind or recipe her for apologizing in ways the build rather than undermine the confidence people have in your abilities -- which includes, perhaps most crucially, demonstrating what you've learned and are doing differently as a result.

Robert I. Sutton's Blog

- Robert I. Sutton's profile

- 266 followers