Rolf Potts's Blog, page 130

April 14, 2011

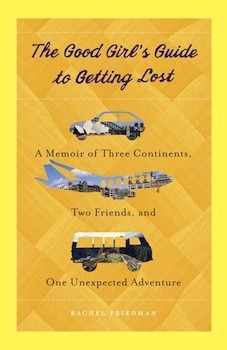

Book review: The Good Girl's Guide to Getting Lost

Do you remember the first trip you took on your own? Mine was to France. I lugged a huge wheeled suitcase, far more cumbersome than today's streamlined wheelies. Every night before I fell asleep, I worried about the next day: whether I could speak French well enough, would miss my train, or knew how to operate the laundry machine in my flat. But it was the experience that started my addiction to traveling and taught me more about myself.

Do you remember the first trip you took on your own? Mine was to France. I lugged a huge wheeled suitcase, far more cumbersome than today's streamlined wheelies. Every night before I fell asleep, I worried about the next day: whether I could speak French well enough, would miss my train, or knew how to operate the laundry machine in my flat. But it was the experience that started my addiction to traveling and taught me more about myself.

In The Good Girl's Guide to Getting Lost, author Rachel Friedman struggles with her orderly and structured life as a parent-pleasing college student and discovers there's more to her future as she takes off for a summer in Ireland—right before her senior year in college. Initially expecting to return at the end of her adventure as old Rachel, to finish school and then get a job (or go to graduate school), she's surprised to find that new Rachel is into vagabonding.

While she does return home to finish college, Rachel then takes off for Australia to visit a friend from her time in Ireland, and then travels with her through South America. Along the way, she finds that her expectations about herself change with each adventure.

The Good Girl's Guide to Getting Lost is a coming-of-age story that serves as a reminder that each trip we take changes us—whether it's someone venturing out for the first time or an experienced traveler. And for those of us who can get overwhelmed with the expectations we have for ourselves, it's a delight to follow another person's path in setting her old expectations aside to make room for new experiences.

The Good Girl's Guide to Getting Lost is now available on Amazon.

April 13, 2011

Vagabonding Case Study: Travis Ball

Age: 34

Hometown: Los Angeles, CA

Quote: "When I started, I was planning on a five-year RTW trip. I think I've decided that travel isn't something you can put limits on like that. I've re-evaluated my outlook and realize that travel is now a lifelong thing for me."

How did you find out about Vagabonding, and how did you find it useful before and during the trip? I first heard about the book while reading "The 4-hour work week" and quickly grabbed it off Amazon. Those two books were exactly what I needed to get motivated for the trip I'm currently on.

How long were you on the road? I left May, 2009 and am currently in Chiang Mai. I should be returning home around August of this year.

Where all did you go? Spain, England, Ireland, Japan, South Korea, China, Hong Kong, Macau, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and heading to Australia and New Zealand.

What was your job or source of travel funding for this journey? After making the commitment to the trip, I did a couple different things. I picked up a second job as a bartender to help save but, more importantly, to learn a skill I could work with overseas. It took two years to pay off my debt and hit my saving goal.

Did you work or volunteer on the road? I'd planned on working as a bartender in Ibzia, my first destination. After three weeks, and three job offers, I couldn't get a job there because I couldn't make the work permit/visa work. Instead, through the contacts I'd made in those early weeks, I started working as a photographer for a British website covering the clubs. By the end of the summer, I was running a team of four photographers and spending 5-6 nights a weeks at the clubs I figured I'd only be able to visit half a dozen times when I arrived.

After Spain, I shot a few festivals in the UK and traveled for two weeks through Ireland before heading to Japan to find a job teaching English. It took two months, but I finally found work and ended up in a small city called Ina about three hours northwest of Tokyo.

Of all the places you visited, which was your favorite? This is like asking what someone's favorite movie is. They're all so different, but the highlights have been Japan, Ireland, China and Thailand.

Was there a place that was your least favorite, or most disappointing, or most challenging? Japan was the most challenging because of the living conditions. Growing up in Los Angeles and teaching in a small, rural part of Japan was a very new experience for me. Instead of movie theaters and public transportation, there were rice fields and my bicycle.

Like all travel experiences (good and bad), it was a great learning experience, and I took advantage of the opportunity to study the language and culture as well as work on personal projects like learning how to cook.

Living in the mountains, we also got a good 4 months of snow, which was something I wasn't used to either. I have to say, I prefer the weather in San Diego, but then who wouldn't?

Did any of your pre-trip worries or concerns come true? Did you run into any problems or obstacles that you hadn't anticipated? The main concerns I faced were making sure I found work in Spain and Japan. In both countries, finding work was harder than I expected, but I made it happen and going through those circumstances and coming out ahead really boosted my confidence and character.

The company I worked for in Japan when bankrupt 7 months into my contract. All the employees were re-hired on three-month contracts and then the situation deteriorated. Instead of working out a full year, I left after about 10 months of work.

Which travel gear proved most useful? Least useful? The camera bag I purchased (the lowepro fastpack 250) has been the most amazing backpack for carrying my gear. I have big pack for my clothes and what not, but needed to find a good bag for my camera, laptop, etc. It's held up well but is now starting to show the scars of travel.

What are the rewards of the vagabonding lifestyle? New Experiences. I've seen a whole other side of the world, met countless interesting people, climbed mountains, learned how to scuba dive, taken part in remarkable festivals, and learned so much about the world and myself.

What are the challenges and sacrifices of the vagabonding lifestyle? Certainly the biggest is time spent away from friends and family. I'm actually shortening my trip so that I can go back and spend some time at home before continuing the trip in 2013.

What lessons did you learn on the road? Countless lessons learned, but the most important lesson has been that I'm capable of so much more and that I can rely on myself and my instincts. Also – life is short, get out and do what you want right now!

How did your personal definition of "vagabonding" develop over the course of the trip? When I started, I was planning on a five-year RTW trip. I think I've decided that travel isn't something you can put limits on like that. I've re-evaluated my outlook and realize that travel is now a lifelong thing for me. This means I can go home and get some work in while visiting friends and family before getting back on the road.

If there was one thing you could have told yourself before the trip, what would it be? Stay on top of your photography and writing – it piles up and gets intimidating after a while.

Any advice or tips for someone hoping to embark on a similar adventure? The first thing is to commit to the trip. Convince yourself you can do it and make the decision. Then, tell everyone you know that you're going. Ignore the naysayers and find some supporters. Also look to the web for inspiration – twitter and travel blogs are filled with advice and information.

When and where do you think you'll take your next long-term journey? Towards the end of 2013, me and a few people I've met during this trip are planning a road trip through Central and South America for about a year.

Twitter: flashpackerhq

Website: flashpackerhq.com

Are you a Vagabonding reader planning, in the middle of, or returning from a journey? Would you like your travel blog or website to be featured on Vagabonding Case Studies? If so, drop us a line at [email protected] and tell us a little about yourself.

Reading books on the road

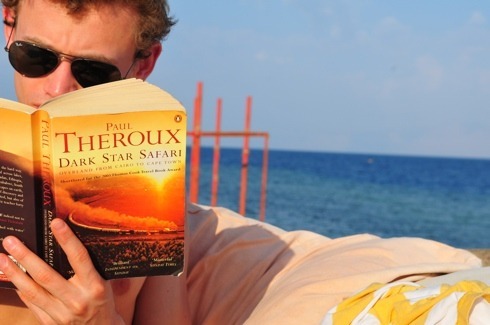

Dahab, Egypt

There are a gazillion things to observe when on the road, and here's one of my favorites: the books people read.

Anytime you see someone reading a book, they're traveling. There is of course the geographic location in which they are actually reading. The English fellow above, for example, is sitting on the upper deck of the restaurant at the Penguin Village in Dahab, Sinai. Behind him is the Gulf of Aqaba, and were he to turn his head 90 degrees to the left, he'd be looking across the water at the barren mountains of Saudi Arabia, and perhaps at a cargo ship en route to or from Eilat, Israel or Aqaba, Jordan. Not a bad place to read.

But there is also the mental journey that a book takes people on. The English fellow in Dahab is reading about Paul Theroux traveling overland from Cairo to Cape Town, and based on where the book is open to I'd guess he's somewhere around Tanzania or Malawi. Any genre, not just a travel narrative, takes the reader on a journey of some sort. (I could say a lot about Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov at this point, but I'll resist the urge.)

Once at a cafe in Beijing, sipping coffee at the start of what would be a 14-month journey across Asia, I was reading Theroux's Fresh Air Fiend and underlined many lines, including these:

Losing a friend to death or absence or misunderstanding is not only a blow to self-esteem but a stun to memory. The sad reflection that we are losing a part of ourselves is true: part of our memory has departed with the lost friend.

I was traveling in China, but with these lines I was traveling elsewhere to, considering the truth of the words — the ways in which relationships make us who we are and the dangers of neglecting or scuttling them, the risks of extended trips away from home, the multi-dimensional tragedy of a childhood friend's recent suicide.

Books are a gift, a way of enriching and shaping our physical journeys. Any books or lines that have struck you? If so, please leave a note in the comment section.

April 11, 2011

When you travel, you're more attentive to the self you bring along

FOR THE TRAVELER

By John O'Donohue

from To Bless the Space Between Us (2008)

(2008)

Every time you leave home,

Another road takes you

Into a world you were never in.

New strangers on other paths await.

New places that have never seen you

Will startle a little at your entry.

Old places that know you well

Will pretend nothing

Changed since your last visit.

When you travel, you find yourself

Alone in a different way,

More attentive now

To the self you bring along,

Your more subtle eye watching

You abroad; and how what meets you

Touches that part of the heart

That lies low at home:

How you unexpectedly attune

To the timbre in some voice,

Opening in conversation

You want to take in

To where your longing

Has pressed hard enough

Inward, on some unsaid dark,

To create a crystal of insight

You could not have known

You needed

To illuminate

Your way.

When you travel,

A new silence

Goes with you,

And if you listen,

You will hear

What your heart would

Love to say.

A journey can become a sacred thing:

Make sure, before you go,

To take the time

To bless your going forth,

To free your heart of ballast

So that the compass of your soul

Might direct you toward

The territories of spirit

Where you will discover

More of your hidden life,

And the urgencies

That deserve to claim you.

May you travel in an awakened way,

Gathered wisely into your inner ground;

That you may not waste the invitations

Which wait along the way to transform you.

May you travel safely, arrive refreshed,

And live your time away to its fullest;

Return home more enriched, and free

To balance the gift of days which call you.

April 8, 2011

Q&A with Brook Silva-Braga, director of 'The China Question'

Brook Silva-Braga at the Bund in Shanghai. All photos courtesy of Brook Silva-Braga.

China is a huge country, and an even bigger topic to tackle in a movie. Filmmaker Brook Silva-Braga took on that daunting challenge in his new documentary, "The China Question." This is the divisive issue that causes American workers to worry, politicians to vacillate, and businesspeople to make deals: "What does China's rise mean for America?"

Marcus Sortijas, Vagablogging's Asia beat editor, interviewed Brook about his film, China, and the vagabonding life.

What was the catalyst that got you started on this project?

In a way, it started with my mom actually, because she has been boycotting "Made in China" products for years now. I think most Americans have a sense that we're helping China become more powerful and that China has pretty different values and priorities than we do.

But I kind of wondered whether my mom was on to something or was just being really naïve. So even though her boycott wasn't the reason I went to China, it did provide a kind of frame to look through: "How does what's happening in China affect us and how should we respond?"

Can you briefly describe your professional background?

Well I studied journalism at New York University and then got a job as a producer for HBO Sports. After a few years of that I quit to go on an around-the-world trip. While I was out there, I shot the backpacking documentary "A Map for Saturday." The movie did well enough for me to launch a production company and keep making independent docs.

Brook Silva-Blaga shooting the giant sand dunes of Dunhuang in western China.

In "A Map for Saturday," you did a trip around the world. How did your experience as a vagabonder help you film "The China Question"?

The experience as a vagabonder is a huge asset for my style of filmmaking. As a vagabonder I travel very light and very cheap, which makes it possible economically to do these types of projects. Using a normal production model, no documentary could afford 100-foreign-shoot days like I had on this project.

But it also helps with content because when you're literally sleeping on someone's floor you get a different interview with them than you would by just meeting in an office, shaking hands and hitting 'record.'

A crowd of Chinese gather around Brook Silva-Blaga's video camera in Hangzhou.

How did you prepare for your trip to China? Any advice for people planning to go?

I tried to make friends through Couchsurfing and that was pretty useful, not just for free places to stay but more so to find English speakers. China is a huge country that rewards extended trips, the longer you have the more interesting your experience will be because there's so much to see outside Shanghai and Beijing.

What were the most difficult obstacles to shooting and traveling in China?

When you get away from the industrialized east coast the level of development plummets and even having a Mandarin translator doesn't help much, since most people just speak their local dialect.

The distances also get really long, so 12 to 18-hour bus rides are typical out west. But to be honest, as I look back at it now I mainly remember all the great parts and have forgotten the headaches.

Could you share any stories about your worst and best moments traveling in China?

Man there were a lot. One crazy one involved being approached by some women in a park in Ningbo. They wanted my girlfriend and I to model for their photo studio.

In China, couples spend thousands of dollars to take elaborate wedding photos long before they're actually married. The studio offered to shoot us for free if they could use the images in their portfolio. So the next day they dressed us up in some gaudy formalwear and paraded us around Ningbo taking "wedding" photos. The whole thing was pretty hilarious.

Brook Silva-Blaga at the Badaling section of the Great Wall to catch the sunrise.

Did you also do post-production in China?

I did the post-production back in the U.S. One thing that sets this film apart from "A Map for Saturday" and "One Day in Africa" is that it has a strong American component. I spent lots of time road-tripping across the U.S. to get that perspective as well. Then I sat with all my footage back in New York and cobbled it together.

From talking to Americans around the country, what were their views on China?

Overall there's just a sense that China is eating our lunch and people have different thoughts on why that's happening and different levels of understanding about the forces at play. But there is a pretty broad pessimism about it. What's a bit surprising–and what I hope the movie will help change–is there isn't all that much talk about what concrete steps we should take to create a more favorable situation.

You interviewed a wide range of people: workers on both sides, scholars, normal people, and of course, your own mother. One group was conspicuously absent: American CEOs. Can you explain why?

One of the surprises of the project for me was how willing Chinese companies were to talk about the work they're doing–they're proud of it.

American companies aren't quite as eager to talk about US/China trade. For starters, it's just unpopular because it's often associated with outsourcing. I attempted to speak with several large American companies–but they tended to suffer from schedules that were too full to speak on-camera.

What was your past experience with China and the Chinese language before this? How did that help or hinder you?

I had never been to China and didn't know a single word of the language. The language gap was definitely a handicap. But there were at least two advantages to being a newcomer.

First, I saw China with totally fresh eyes and, second, I hadn't invested years learning the language. So, if at the end of the project I was banned from China because of the film, that wouldn't be so devastating. I think it made me a bit more fearless.

At one point in the film, you did say that your documentary would probably get banned in China. (Note: This was due to a segment on the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests) Has that happened? Was there any backlash from the PRC government?

The Chinese government is nothing if not savvy. By now they've realized that boldly condemning something only brings more attention to it, so their retribution is usually subtle.

I know a number of writers who have written gently critical books about China and found it suddenly very difficult to get a visa to enter the country. Another popular tactic is stealth attacks on their websites.

It's too soon to know if they'll pay me that type of attention. But it's pretty certain my film won't be officially welcomed into the country. Only 20 foreign films are allowed in each year.

I enjoyed how you re-visited Susu, the woman driver who served as your translator, later in the film. The young teacher in Xinjiang was also a colorful character. Have you heard any recent news from the Chinese people you spoke to?

I'm still in touch with several of them and life continues to evolve in that rapid way it does in China. The big change we see in Susu at the end of the film has continued, she is certainly no longer a driver.

Did you have any preconceived ideas about China when you started? How did your opinions change as you filmed this project?

I didn't have any major shifts of opinion, just a much finer understanding of lots of things. When you read that it's a fast-growing economy you may understand what that means. But then you meet someone doing manual labor and then return a year later to find them making close to six-figures in an office job. It gives you a different appreciation of what is going on.

Thank you for talking with us. Best of luck with your film.

To find out more, watch the trailer, and get more information, please visit the film's website: The China Question.

Q&A with Brook Silva-Blaga, director of 'The China Question'

Brook Silva-Braga at the Bund in Shanghai. All photos courtesy of Brook Silva-Braga.

China is a huge country, and an even bigger topic to tackle in a movie. Filmmaker Brook Silva-Braga took on that daunting challenge in his new documentary, "The China Question." This is the divisive issue that causes American workers to worry, politicians to vacillate, and businesspeople to make deals: "What does China's rise mean for America?"

Marcus Sortijas, Vagablogging's Asia beat editor, interviewed Brook about his film, China, and the vagabonding life.

What was the catalyst that got you started on this project?

In a way, it started with my mom actually, because she has been boycotting "Made in China" products for years now. I think most Americans have a sense that we're helping China become more powerful and that China has pretty different values and priorities than we do.

But I kind of wondered whether my mom was on to something or was just being really naïve. So even though her boycott wasn't the reason I went to China, it did provide a kind of frame to look through: "How does what's happening in China affect us and how should we respond?"

Can you briefly describe your professional background?

Well I studied journalism at New York University and then got a job as a producer for HBO Sports. After a few years of that I quit to go on an around-the-world trip. While I was out there, I shot the backpacking documentary "A Map for Saturday." The movie did well enough for me to launch a production company and keep making independent docs.

Brook Silva-Blaga shooting the giant sand dunes of Dunhuang in western China.

In "A Map for Saturday," you did a trip around the world. How did your experience as a vagabonder help you film "The China Question"?

The experience as a vagabonder is a huge asset for my style of filmmaking. As a vagabonder I travel very light and very cheap, which makes it possible economically to do these types of projects. Using a normal production model, no documentary could afford 100-foreign-shoot days like I had on this project.

But it also helps with content because when you're literally sleeping on someone's floor you get a different interview with them than you would by just meeting in an office, shaking hands and hitting 'record.'

A crowd of Chinese gather around Brook Silva-Blaga's video camera in Hangzhou.

How did you prepare for your trip to China? Any advice for people planning to go?

I tried to make friends through Couchsurfing and that was pretty useful, not just for free places to stay but more so to find English speakers. China is a huge country that rewards extended trips, the longer you have the more interesting your experience will be because there's so much to see outside Shanghai and Beijing.

What were the most difficult obstacles to shooting and traveling in China?

When you get away from the industrialized east coast the level of development plummets and even having a Mandarin translator doesn't help much, since most people just speak their local dialect.

The distances also get really long, so 12 to 18-hour bus rides are typical out west. But to be honest, as I look back at it now I mainly remember all the great parts and have forgotten the headaches.

Could you share any stories about your worst and best moments traveling in China?

Man there were a lot. One crazy one involved being approached by some women in a park in Ningbo. They wanted my girlfriend and I to model for their photo studio.

In China, couples spend thousands of dollars to take elaborate wedding photos long before they're actually married. The studio offered to shoot us for free if they could use the images in their portfolio. So the next day they dressed us up in some gaudy formalwear and paraded us around Ningbo taking "wedding" photos. The whole thing was pretty hilarious.

Brook Silva-Blaga at the Badaling section of the Great Wall to catch the sunrise.

Did you also do post-production in China?

I did the post-production back in the U.S. One thing that sets this film apart from "A Map for Saturday" and "One Day in Africa" is that it has a strong American component. I spent lots of time road-tripping across the U.S. to get that perspective as well. Then I sat with all my footage back in New York and cobbled it together.

From talking to Americans around the country, what were their views on China?

Overall there's just a sense that China is eating our lunch and people have different thoughts on why that's happening and different levels of understanding about the forces at play. But there is a pretty broad pessimism about it. What's a bit surprising–and what I hope the movie will help change–is there isn't all that much talk about what concrete steps we should take to create a more favorable situation.

You interviewed a wide range of people: workers on both sides, scholars, normal people, and of course, your own mother. One group was conspicuously absent: American CEOs. Can you explain why?

One of the surprises of the project for me was how willing Chinese companies were to talk about the work they're doing–they're proud of it.

American companies aren't quite as eager to talk about US/China trade. For starters, it's just unpopular because it's often associated with outsourcing. I attempted to speak with several large American companies–but they tended to suffer from schedules that were too full to speak on-camera.

What was your past experience with China and the Chinese language before this? How did that help or hinder you?

I had never been to China and didn't know a single word of the language. The language gap was definitely a handicap. But there were at least two advantages to being a newcomer.

First, I saw China with totally fresh eyes and, second, I hadn't invested years learning the language. So, if at the end of the project I was banned from China because of the film, that wouldn't be so devastating. I think it made me a bit more fearless.

At one point in the film, you did say that your documentary would probably get banned in China. (Note: This was due to a segment on the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests) Has that happened? Was there any backlash from the PRC government?

The Chinese government is nothing if not savvy. By now they've realized that boldly condemning something only brings more attention to it, so their retribution is usually subtle.

I know a number of writers who have written gently critical books about China and found it suddenly very difficult to get a visa to enter the country. Another popular tactic is stealth attacks on their websites.

It's too soon to know if they'll pay me that type of attention. But it's pretty certain my film won't be officially welcomed into the country. Only 20 foreign films are allowed in each year.

I enjoyed how you re-visited Susu, the woman driver who served as your translator, later in the film. The young teacher in Xinjiang was also a colorful character. Have you heard any recent news from the Chinese people you spoke to?

I'm still in touch with several of them and life continues to evolve in that rapid way it does in China. The big change we see in Susu at the end of the film has continued, she is certainly no longer a driver.

Did you have any preconceived ideas about China when you started? How did your opinions change as you filmed this project?

I didn't have any major shifts of opinion, just a much finer understanding of lots of things. When you read that it's a fast-growing economy you may understand what that means. But then you meet someone doing manual labor and then return a year later to find them making close to six-figures in an office job. It gives you a different appreciation of what is going on.

Thank you for talking with us. Best of luck with your film.

To find out more, watch the trailer, and get more information, please visit the film's website: The China Question.

April 7, 2011

Passport day

Are you one of the 30 percent of U.S. citizens who has a passport? If not, and you're planning on traveling out of the country any time in the next year, mark Saturday, April 9 on your calendar. On that day, the U.S. Department of State will host its third annual "Passport Day in the U.S.A.," allowing citizens to apply for a passport book or passport card without an appointment at any one of the participating regional passport agencies or participating passport acceptance facilities, including post offices.

Are you one of the 30 percent of U.S. citizens who has a passport? If not, and you're planning on traveling out of the country any time in the next year, mark Saturday, April 9 on your calendar. On that day, the U.S. Department of State will host its third annual "Passport Day in the U.S.A.," allowing citizens to apply for a passport book or passport card without an appointment at any one of the participating regional passport agencies or participating passport acceptance facilities, including post offices.

That is, unless there's a government shutdown. While the State Department hasn't made an official statement on how a shutdown would affect Passport Day, passport offices were closed the last time a government shutdown occurred.

Even though no appointments are necessary, there are two things you can do to speed your visit. First, check the list of participating locations (listed by state) to make sure you know the closest spot to get your application processed. Second, find the form that applies to your situation, and fill it out in advance.

While it won't speed things up, knowing how much you'll have to pay is helpful. Aside from the regular fees, there is an optional $60 fee to expedite your application if you absolutely must have it soon. Routine service (as of April 3, 2011) takes from 4-6 weeks, while expedited service takes 2-3 weeks.

April 6, 2011

How to Travel the World on $50 a Day: a new Ebook from Nomadic Matt

Many Vagablogging readers are familiar with Matt Kepnes, or Nomadic Matt. Kepnes's website is packed full of information on travel deals, travel tips, travel guides, and loads of interesting travel tales suited to any genre. Now Kepnes has taken the next step and has published his own Ebook.

Many Vagablogging readers are familiar with Matt Kepnes, or Nomadic Matt. Kepnes's website is packed full of information on travel deals, travel tips, travel guides, and loads of interesting travel tales suited to any genre. Now Kepnes has taken the next step and has published his own Ebook.

Kepnes's book is a smooth read. Even over the details of dollars, budgets, and savings options, it never reads like a dry financial manual. Kepnes's book documents specific dollar amounts for many elements of his travels. He starts with how to save money before you even hit the road by detailing the more advantageous international banking options and airline carriers.

Kapnes's book isn't just for the new traveler in the beginning stages of planning out their trip. There is a lot of useful information that, even after years of long-term stints on the road, I still haven't quite been able to work out, like making air miles work for you, or all of the ropes and rules of upgrading to business class on those long flights. Sure, there are loads of details for beginning travelers, like how to pick the right backpack for the road or how to save for your trip before you depart. Though there is something for everyone in this book. Whether you're a novice when it comes to air miles, or if you're trying to decipher the endless web of ESL jobs or volunteer options abroad.

There is also a Destinations section in the book, where Kepnes offers readers a look at likely travel budgets for areas on all continents of the globe. He even includes budgets for activities popular to a particular destination, like scuba diving in Southeast Asia. Kepnes also compiles a list of great hostels and budget guesthouses for various locations, along with discount coupons should you be in the area and decide check out one of the accommodations.

You can download a PDF format of the book from Kepnes's website for US$14. The book is also available for your Kindle or Ipad.

Vagabonding Case Study: Paul Karl Lukacs

Hometown: Los Angeles, CA

Quote: "You may start to question who you are and where – or if – you still fit into the world."

How did you find out about Vagabonding, and how did you find it useful? Rolf's book! It's a cliché to say that a book changed your life, but that's what Rolf's did.

I was like most Americans. I thought that "travel" meant spending a week in an expensive hotel and that long-term travel was reserved for college kids from wealthy families. It blew my mind to realize that living abroad or on the road – sometimes, in the plushest or most beautiful surroundings – could cost a fraction of what it cost to live in Los Angeles.

When did you hit the road? Originally, I flew out in mid-2006 and stayed abroad for a year. I came back to LA just as the recession was starting – great timing, eh? – and was somewhat taken aback by the negative reaction to my vagabonding. So I took graduate courses in Asian history at UCLA, and, when those ended in spring 2010, I left again.

What do you mean by a "negative reaction" to your vagabonding? Before I left, many people offered their compliments and promised to hook me up with job interviews when I returned. Very few came through. The recession was certainly a factor, but several people sheepishly admitted they couldn't champion my resume because "my boss will think your traveling is weird" or "we're only interviewing people already in full-time jobs."

My strong advice to would-be vagabonders is to consider the culture of your industry and to sketch out a re-entry plan before you leave. I am a lawyer, which is a conformist profession with fairly rigid career tracks. The career paths in tech and media are apparently more fluid, with people moving between traditional employment, time off and self-employment/start-up work.

How do you fund your current travels? I do business under the name The Nomad Lawyer, and I research and draft legal filings and memoranda for other attorneys. For example, a lawyer may be served with an emergency motion on Friday but not have the time to deal with it over the weekend. She zaps it to me, and I draft the opposition, which lands in her In Box when she wakes up Monday morning. I also contribute pieces to various periodicals.

How long do you plan to travel this time? I'm at the point where "vagabonding" is shading into "expat life." The United States is the greatest and freest place on earth if your goal is to maximize absolute wealth or status. If your goal is different – say, to maximize freedom or experiences or relative wealth – other nations may be a better fit.

What is your style of vagabonding? It's an intense form of hanging out. I pick a country, see how long they'll let me stay and then move into a sublet or a serviced apartment for a few months, taking periodic trips to neighboring countries.

What gear do you use? All I need is a quiet room with a fast and reliable internet connection, a sturdy chair and a good-sized working surface like a desk or a dining room table. That being said, it's amazing how difficult it can sometimes be to find all of those components in one place for the $500 to $1,000 a month I'm willing to pay for lodging.

Once I find a suitable flat, I usually buy a cheap inkjet printer – so that's about $150 including paper and ink – because I'm old enough to want to edit and proofread documents on paper before I send them out.

Where have you been? East and Southeast Asia mostly, because it's cheap, and I have an academic interest in the region, and many of the governments are easy with visas. Three months in Paris was fantastic, but pricey. I tend to rotate between low-cost destinations like Phuket, Thailand, and higher-cost places like Hong Kong, where I am now.

What are the rewards and sacrifices of the vagabonding lifestyle? All the words begin with S.

As a vagabond, you can have almost anything. You can have Security, if you budget well or work hard. You can have a Spouse, and you can go on the road with your Spawn. But you cannot have Stuff, because that's too cumbersome.

And – this may be the hardest part for people to cope with over time – the longer you are on the road, the more you are stripped of Status. Your place in the world is heavily determined by your job, your neighborhood, your visible consumption patterns, and the institutions with which you are affiliated. When you are vagabonding, most of these fall away. Other people find it increasingly difficult to peg you, and you may start to question who you are and where – or if – you still fit into the world. That might be the sign that it's time to either go home or settle down as an expat.

If I Google your name, the main thing that comes up is "I Was Detained By The Feds For Not Answering Questions." What's that about? U.S. citizens have an absolute right to re-enter their country. The U.S. cannot condition the right of re-entry upon your submission to an interrogation about where you were, who you saw, etc. You have a Fifth Amendment right to silence which applies at the border, so you do not have to answer the questions posed to you orally by Customs and Border Protection officers. Of course, if you don't, you will be hassled, and I wrote up an account of my being detained at SFO for refusing to submit. The post went viral, and I'm happy that more than one million people now know they have a right not to answer CBP's questions.

Website: nomadlaw.com

Are you a Vagabonding reader planning, in the middle of, or returning from a journey? Would you like your travel blog or website to be featured on Vagabonding Case Studies? If so, drop us a line at [email protected] and tell us a little about yourself.

April 4, 2011

Try everything once, while you have the time

"From childhood I had dreamed of climbing Fujiyama and the Matterhorn, and I had planned to charge Mount Olympus in order to visit the gods that dwelled there. I wanted to swim the Hellespont where Lord Byron swam, float down the Nile in a butterfly boat, make love to a pale Kashmiri maiden beside the Shalimar, dance to the castanets of Granada gypsies, commune in solitude with the moonlit Taj Mahal, hunt tigers in a Bengal jungle — try everything once. …I wanted to realize my youth while I still had it, and yield to temptation before increasing years and responsibilities robbed me of the courage."

–Richard Halliburton, quoted by Lawrence Wright, in In the New World (1988)

Rolf Potts's Blog

- Rolf Potts's profile

- 321 followers