Rolf Potts's Blog, page 7

September 3, 2015

Vagabonding Case Study: Cherie and Chris

Age: Cherie: 42 Chris: 42

Hometown: Cherie: Melbourne, FL Chris: San Francisco, CA

Quote: “Don’t worry so much.. just do it!” ”May the bandwidth be with you”

How did you find out about Vagabonding, and how did you find it useful before and during the trip?

I believe we found the Vagabonding.com community in the general course of trying to find others who are also traveling full time as a lifestyle. It’s been great to connect with others, and know we’re not alone!

How long have you been on the road?

Chris hit the road full time in April 2006, and we met a few months later. Cherie joined him on the road full time in May 2007.

Where did you go?

Since our original case study, we parked & sold the 17′ Travel Trailer. For a few months, we rented a small cottage in the US Virgin Islands and then we returned to the states we pursued purchasing a 1961 vintage highway bus conversion.

For the past 4 years, we’ve been traveling full time in the US while updating and upgrading the bus to become a geeked out vintage classic. We occasionally park the bus, and embark on other adventures – such as this summer we just spent 7 weeks traveling by rail, boat and bus to and from Alaska.

What was your job or source of travel funding for this journey?

We shut down the custom software development business about 2 years ago, after Cherie’s father passed away (it was a family business).

We’ve been working since then to shift our income sources over to be more passive as we continued our mobile app development (we now have 3 apps out – Coverage?, State Lines and US Public Lands – all tools for traveling in the US).

We also wrote a book on mobile internet (The Mobile Internet Handbook) and launched a resource center site at www.RVMobileInternet.com where we track the industry news and provide resources for our RVing community to keep online as they travel. We’re seeing more and more folks hitting the road and working online, connectivity is a vital element of that.

We also love helping companies launch unique offerings within our communities that better all of our lives. In the past couple of years we’ve helped launch a social network for RVers called RVillage.com, and a support network for working aged RVers called Xscapers.com providing resources like domicile, mail forwarding, job boards, health insurance and more.

Did you work or volunteer on the road?

We have continued to integrate in volunteer work. For the past two years, we volunteered as tour guides at a history lighthouse on the coast of Oregon.

We did get started with doing work with the Red Cross, but our working life keeps us too busy to be able to get too involved.

Of all the places you visited, which was your favorite?

We cringe when someone asks us this question still to this day. When our current location is no longer our favorite, we move.

Was there a place that was your least favorite, or most disappointing, or most challenging?

Suburbs and strip malls are always the most draining places to experience.

We’ve also come to dislike tightly packed in RV Parks and have optimized our setup to allow us to thrive in wider open places with great views.

Did any of your pre-trip worries or concerns come true? Did you run into any problems or obstacles that you hadn’t anticipated?

Yup, most of our pre-trip worries have come true. And you know what? We thrived. We’ve experienced mechanical breakdowns, safety threats, almost running out of gas, inclement weather, getting lost, logistical snafus and more. You just learn to go with the flow and approach things with agility. Once you really embrace that ‘the worst that can happen’ isn’t so bad – it’s all good.

Which travel gear proved most useful? Least useful?

Our mobile technology (MacBook Pros, iPads, iPhones) have definitely proven core to our lifestyle and work. And our solar panels keep us charged up and able to work from amazing remote locations without worrying about needing to plug in.

Also in the past several years, cellular technology has come a long way – allowing many of us to work remotely from anywhere while not being dependent on public WiFi. This has given us a tremendous amount of freedom and opened up a lot more options.

What are the rewards of the vagabonding lifestyle?

Variety, exposure, knowledge, learning, connection, adventure and having no regrets. The more we travel, the more amazing people we’ve been able to meet and connect with.

What are the challenges and sacrifices of the vagabonding lifestyle?

Our quest for community continues, and it’s gotten even more flourishing in the past few years. More and more of our peers are hitting the road, and we regularly meet up with them. With tools like RVillage, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and blogs – we’re all able to keep in touch much easier.

So, we’d probably say that one of the biggest challenges of a vagabonding lifestyle, particularly in the US is healthcare these days. Especially as we get older, it will become more of a concern. Our systems just aren’t setup to support a mobile population – it’s difficult to find doctors you trust, and health plans that cover us as we roam. On the plus side, options for self care and telehealth are increasing.

What lessons have you learned on the road?

Chill, relax, go with the flow, and don’t become overly tied to any set schedule. There is no one right way to do anything.

How did your personal definition of “vagabonding” develop over the course of the trip?

It really hasn’t changed…

If there was one thing you could have told yourself before the trip, what would it be?

Don’t worry so much.. just do it!

Any advice or tips for someone hoping to embark on a similar adventure?

Get started, and work out the details along the way. And — don’t get caught up in the details too much. Trust in your ability to adapt, and be present to enjoy the experience.

When and where do you think you’ll take your next long-term journey?

Almost 10 years now on the road, and still loving it. Our current intention is for our bus conversion to be our US mobile home base that we might park for a few months here and there and explore other travel styles.

Read more about Cherie and Chris on their website, Technomadia.

Are you a Vagabonding reader planning, in the middle of, or returning from a journey? Would you like your travel blog or website to be featured on Vagabonding Case Studies? If so, drop us a line at [email protected] and tell us a little about yourself.

Planning a Career Break?

Sign up for the free 30 day e-course >

Image: Victor Svensson (flickr)

Original article can be found here: Vagabonding Case Study: Cherie and Chris

August 27, 2015

Vagabonding Case Study: Karol Gajda

Age: 34

Hometown: I was born in Wrocław, Poland, but I grew up in Michigan.

Quote: This changes often so I’ll choose one of my favorites that can be used along the vagabonding theme.

“There is no tomorrow! There is no tomorrow! There is no tomorrow!” – Apollo Creed, Rocky III

How did you find out about Vagabonding, and how did you find it useful before and during the trip?

I heard about it through 4 Hour Work Week about 3 years ago. I immediately picked it up and devoured it. I had never gone on any sort of long term travel before so Vagabonding was exceptionally useful. If for no other reason than inspiration.

How long were you on the road?

I left the US on Sept 1, 2009 and, technically, I’m still on the road. But I’ve been mostly back in Wrocław, Poland since mid-2012.

Where did you go?

Mostly Poland for the past 3 years. Prior to that a few months here and there in each of Australia, New Zealand, India, Thailand, Panama, Costa Rica, and Hungary. I also spent a couple weeks or less in approximately 2 dozen more countries. And I spent probably 1 cumulative year in the US over the past 6 years. Mostly in Austin, TX.

What was your job or source of travel funding for this journey?

I’ve been self-employed in marketing, since the year 2000.

Did you work or volunteer on the road?

Work, yes. I also volunteered a few times, but rarely.

Of all the places you visited, which was your favorite?

My favorite cities in the world used to be Austin, TX, Chiang Mai, Thailand, and Wrocław, Poland. But I wouldn’t necessarily say that anymore. Currently, I have no favorite.

Was there a place that was your least favorite, or most disappointing, or most challenging?

Costa Rica has probably been the most overrated and underwhelming place I’ve visited. Is the Arenal volcano still being marketed as active? That was definitely the most disappointing experience in my least favorite country. I spent a month in Costa Rica and I don’t plan on returning. Although I did find gallo pinto tasty so CR wasn’t all bad.

Which travel gear proved most useful? Least useful?

My laptop, by far, has been most useful. I have a 2010 13” Macbook Air that has served me well for nearly 5 years now. I don’t have a least useful piece of gear. I use everything I pack and I pack everything in a 36L backpack with room to spare, as well as a small messenger bag for the laptop.

What are the rewards of the vagabonding lifestyle?

Generally, it’s the people I’ve met. Even though I don’t keep in touch or remember most of them.

What are the challenges and sacrifices of the vagabonding lifestyle?

Relationships. I got married so the romantic relationship worked out! But friendships are much more difficult when you know your time in a place is limited and I feel like most of my older friendships have suffered due to being out of sight and out of mind.

What lessons did you learn on the road?

This will probably surprise a lot of people, but I learned that I actually want to move back to the US for an extended period of time. There is a lot there I still haven’t seen and it will be nice to be nearer to friends and family. To put it more succinctly, I learned that relationships matter and a person like me has trouble with them if they have geographical constraints.

How did your personal definition of “vagabonding” develop over the course of the trip?

I would liken it to absolute freedom. Being able to do almost anything at any time. Although, if I’m being honest, I now prefer a non-vagabonding lifestyle with stints of vagabonding thrown in.

If there was one thing you could have told yourself before the trip, what would it be?

You started too late. But better now than never. Go, go, go!

Any advice or tips for someone hoping to embark on a similar adventure?

It’s not for everyone and don’t do it because you read an article or saw some blogger’s edited view point. Do it because you want to. And if you want to, do it while you’re healthy enough to enjoy it.

When and where do you think you’ll take your next long-term journey?

A road trip around the US, hopefully in 2016.

Read more about Karol on his website, Karol.Gajda.

Are you a Vagabonding reader planning, in the middle of, or returning from a journey? Would you like your travel blog or website to be featured on Vagabonding Case Studies? If so, drop us a line at [email protected] and tell us a little about yourself.

Ready plan a Round The World adventure?

Sign up for the free e-course >

Image: Andi Campbell-Jones (flickr)

Original article can be found here: Vagabonding Case Study: Karol Gajda

August 20, 2015

One Hundred Percent American, by Ralph Linton

American anthropologist Ralph Linton wrote the following essay, which appeared in the American Mercury in 1937. Published half a decade before “globalization” became a buzz-word, it humorously illustrates how everyday routine in modern America is the sum of years of global human ingenuity.

“One Hundred Percent American”

There can be no question about the average American’s Americanism or his desire to preserve this precious heritage at all costs. Nevertheless, some insidious foreign ideas have already wormed their way into his civilization without his realizing what was going on. Thus dawn finds the unsuspecting patriot garbed in pajamas, a garment of East Indian origin; and lying in a bed built on a pattern which originated in either Persia or Asia Minor. He is muffled to the ears in un-American materials: cotton, first domesticated in India; linen, domesticated in the Near East; wool from an animal native to Asia Minor; or silk whose uses were first discovered by the Chinese. All these substances have been transformed into cloth by methods invented in Southwestern Asia. If the weather is cold enough he may even be sleeping under an eiderdown quilt invented in Scandinavia.

On awakening he glances at the clock, a medieval European invention, uses one potent Latin word in abbreviated form, rises in haste, and goes to the bathroom. Here, if he stops to think about it, he must feel himself in the presence of a great American institution; he will have heard stories of both the quality and frequency of foreign plumbing and will know that in no other country does the average man perform his ablutions in the midst of such splendor. But the insidious foreign influence pursues him even here. Glass was invented by the ancient Egyptians, the use of glazed tiles for floors and walls in the Near East, porcelain in China, and the art of enameling on metal by Mediterranean artisans of the Bronze Age. Even his bathtub and toilet are but slightly modified copies of Roman originals. The only purely American contribution to tile ensemble is tile steam radiator, against which our patriot very briefly and unintentionally places his posterior.

In this bathroom the American washes with soap invented by the ancient Gauls. Next he cleans his teeth, a subversive European practice which did not invade America until the latter part of the eighteenth century. He then shaves, a masochistic rite first developed by the heathen priests of ancient Egypt and Sumer. The process is made less of a penance by the fact that his razor is of steel, an iron-carbon alloy discovered in either India or Turkestan. Lastly, he dries himself on a Turkish towel.

Returning to the bedroom, the unconscious victim of un-American practices removes his clothes from a chair, invented in the Near East, and proceeds to dress. He puts on close-fitting tailored garments whose form derives from the skin clothing of the ancient nomads of the Asiatic steppes and fastens them with buttons whose prototypes appeared in Europe at the Close of the Scone Age. This costume is appropriate enough for outdoor exercise in a cold climate, but is quite unsuited to American summers, steam-heated houses, and Pullmans. Nevertheless, foreign ideas and habits hold the unfortunate man in thrall even when common sense tells him that the authentically American costume of gee string and moccasins would be far more comfortable. He puts on his feet stiff coverings made from hide prepared by a process invented in ancient Egypt and cut to a pattern which can be traced back to ancient Greece, and makes sure that they ire properly polished, also a Greek idea. Lastly, he tics about his neck a strip of bright-colored cloth which is a vestigial survival of the shoulder shawls worn by seventeenth century Croats. He gives himself a final appraisal in the mirror, an old Mediterranean invention, and goes downstairs to breakfast.

Here a whole new series of foreign things confronts him. His food and drink are placed before him in pottery vessels, the proper name of which — china — is sufficient evidence of their origin. His fork is a medieval Italian invention and his spoon a copy of a Roman original. He will usually begin the meal with coffee, an Abyssinian plant first discovered by the Arabs. The American is quite likely to need it to dispel the morning-after effects of overindulgence in fermented drinks, invented in the Near East; or distilled ones, invented by the alchemists of medieval Europe. Whereas the Arabs took, their coffee straight, he will probably sweeten it with sugar, discovered in India; and dilute it with cream, both the domestication of cattle and the technique of milking having originated in Asia Minor.

If our patriot is old-fashioned enough to adhere to the so-called American breakfast, his coffee will be accompanied by an orange, domesticated in the Mediterranean region, a cantaloupe domesticated in Persia, or grapes domesticated in Asia Minor. He will follow this with a bowl of cereal made from grain domesticated in the Near East and prepared by methods also invented there. From this he will go on to waffles, a Scandinavian invention with plenty of butter, originally a Near Eastern cosmetic. As a side dish he may have the egg of a bird domesticated in Southeastern Asia or strips of the flesh of an animal domesticated in the same region, which has been salted and smoked by a process invented in Northern Europe.

Breakfast over, he places upon his head a molded piece of felt, invented by the nomads of

Eastern Asia, and, if it looks like rain, puts on outer shoes of rubber, discovered by the ancient Mexicans, and takes an umbrella, invented in India. He then sprints for his train–the train, not sprinting, being in English invention. At the station he pauses for a moment to buy a newspaper, paying for it with coins invented in ancient Lydia. Once on board he settles back to inhale the fumes of a cigarette invented in Mexico, or a cigar invented in Brazil. Meanwhile, he reads the news of the day, imprinted in characters invented by the ancient Semites by a process invented in Germany upon a material invented in China. As he scans the latest editorial pointing out the dire results to our institutions of accepting foreign ideas, he will not fail to thank a Hebrew God in an Indo-European language that he is a one hundred percent (decimal system invented by the Greeks) American (from Americus Vespucci, Italian geographer).

–Ralph Linton, “One Hundred Per-Cent American,” from the American Mercury (1937)

Image: Jn1776 (flickr)

Original article can be found here: One Hundred Percent American, by Ralph Linton

August 18, 2015

Vagabonding Field Report: Hoi An, Vietnam

A stop in Hoi An should be at the top of everyone’s list when traveling through Vietnam. It’s halfway between Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi, two major destinations in Vietnam, but has a quieter more laid back feel. Hoi An is famous for their tailors, food, and silk lanterns. Many come here to have a custom suit or dress made. Sitting on a river delta and a short ride to the beach, it’s surrounded by rice paddies and smells like a combination of soup and fresh rice. The old town also happens to be a world famous UNESCO World Heritage Site which makes the ancient city center well preserved and colorful. We came here to relax by the river, bicycle and have a suit made.

Cost Per Day:

Staying in the old city gets costly but we stayed at a new villa that had weekly rates and few reviews. This can be a bit risky but can often pay off because new hotels are looking for good reviews and constant feedback about how they can do better. It was about 3km outside of the city center and provided free bicycle rentals, free breakfast and coffee, and had a shared kitchen, and excellent wifi for working. For one week we paid $150 USD which was far below the average in the area. Food in the old town ranged from nicer restaurants with leafy gardens and fancy cocktails to street vendors making pho and cau lao for only $1 USD.

A typical day:

After enjoying traditional Vietnamese coffee and an omelette by our koi pond we would spend the morning working from our patio overlooking massive rice paddies full of colorful workers in conical hats. A quick bike ride into the old city for some beef pho and La Rue beer would fill us up before going in for another fitting at the tailor for the suit we were having made. The sun would be hot and high in the sky and we would continue on our bikes to the beach. A beautiful breezy ride through rice fields led us to the ocean where locals and tourists mixed in the sand and played in the water. As the sun set we would ride back into town and park our bikes in the old city and walk through the lantern lit streets and find a restaurant with a candlelit atmosphere and Vietnamese food with a modern take, often also an NGO supporting local street kids.

What I like:

The city is incredibly colorful. Between the bright yellow painted houses and buildings in the old town and the thousands of silk lanterns hanging everywhere there are also people dressed in bright patterns and conical hats bicycling around. Beer and food is cheap, transportation is laid back, and food options are plentiful with a lot of up and coming chefs making their mark with a twist on tradition dishes.

Where next:

Currently back home in Vancouver, Canada visiting friends and family and doing some life errands and tying up loose ends. I’ll be heading back to Indonesia in September to complete the PADI instructor course to make diving my profession. More to share on that next time!

Image: Maks08 (shutterstock)

Original article can be found here: Vagabonding Field Report: Hoi An, Vietnam

August 16, 2015

Vagabonding Case Study: The Candy family

The Candy family of Get In The Hot Spot

Age: I celebrated my 40th while we were away. My husband is 6 years older than me and when we left our kids were 2, 5 and 8 years old

Hometown: I’m from the UK but we lived in New Zealand for 10 years before this trip and all our kids are Kiwis. We’ve since moved to Queensland in Australia.

Quote: “What we did was brave, some might say mad, but it paid off for us in every way.”

How did you find out about Vagabonding, and how did you find it useful before and during the trip? Online. I find the Vagabonding concept a brilliant way to feel validated in our choices of dragging our kids away from their home, toys, friends and schooling. Most people don’t understand the urge to do something like that so it’s good to read about other people who do get it.

How long were you on the road? About 18 months.

Where did you go? Central America. We started in Guatemala and travelled round Panama, Nicaragua and Costa Rica with the aim of moving to Panama. But we preferred Costa Rica and lived in the south of Costa Rica for over a year. In the end it wasn’t the right place for us to educate our three children, especially our oldest son, so we moved to Australia. But we’re lucky the whole family got to experience life in the jungle and enjoy total immersion in the Latin American culture and language.

What was your job or source of travel funding for this journey? We sold our house and lived off the interest and income from our savings. Because of the global financial crisis and the recession we actually ended up being better off by bumming round Central America for 18 months than we would have been if we’d stayed in our house and carried on working. What we did was brave, some might say mad, but it paid off for us in every way.

Did you work or volunteer on the road? We did plan to set up our own business in Central America – we work from home designing websites and blogs – but in the end we couldn’t get Internet so that put an end to our idea of working. I tried to help out in our kids’ schools. They went to public schools and I’m a qualified English teacher so I wanted to volunteer but unlike in New Zealand, where parental help is actively encouraged, in Costa Rica it’s not wanted. The Costa Rican teachers found it very strange when I explained how I helped kids with reading in New Zealand and said in Costa Rica they prefer to lock the kids in and the parents out.

Of all the places you visited, which was your favorite? The Southern Zone in Costa Rica close to Dominical where we lived. The beaches are gorgeous and the wildlife spectacular. We had monkey, toucans, iguanas and snakes in the garden and even got scorpions, bats and birds in the house. It’s very close to the Osa Peninsula, one of the most biologically diverse places in the world. Our kids learnt to recognise all the jungle animals including the four different types of monkey that live there and name them in English and Spanish – when our youngest arrived in Australia she’d forgotten what a sheep was!

Was there a place that was your least favorite, or most disappointing, or most challenging? Antigua in Guatemala was our first stop. The architecture’s stunning but we found it very busy and stressful hanging out there with the kids. Northern Guatemala was much more relaxing and less crowded.

Did any of your pre-trip worries or concerns come true? Just before we left, people started telling me that Guatemala was the kidnapping capital of the world and acted like I was the worst mum in the world for taking my kids there. Of course our kids were safe. We went to a restaurant in Guatemala City with a bouncy castle outside and the kids played on that while a guard with a big gun watched on – it sounds strange but we kept safe and I wouldn’t put my kids at risk. The main thing that went wrong was when our 2 year old broke her arm about a week before we left. I got the doctor to put on an old-fashioned plaster cast so I could take if off myself and avoid a trip to a Guatemalan hospital. When you’ve got kids accidents do happen. Max, then aged 6, had to go to hospital twice in Costa Rica for stitches and x-rays. It wasn’t a fun experience but he’s made a full recovery.

My husband and I have travelled all over the world and are quite streetwise. We carried all our valuables around Central America in a Pooh Bear backpack thinking it would be the last target for theft and it worked, we didn’t have any problems with crime and nothing got stolen.

Did you run into any problems or obstacles that you hadn’t anticipated? When we finally decided where we wanted to move to it took us three weeks to find a rental house so we had to stay in cabinas for longer than we wanted. But the owners were lovely and let us use their kitchen and practice our bad spanish on them so we ended up making good friends.

Which travel gear proved most useful? Least useful? A decent knife is great for cutting fruit and eating on the go and I had a good spanish course on my ipod which helped me get up to speed with the language fast. I always seem to carry a big medical kit with me that never gets used! I suppose that’s like travel insurance though – if I didn’t have it I’d have needed it.

What are the rewards of the vagabonding lifestyle? Taking new challenges, improving your confidence, experiencing new cultures and seeing and doing things you’d never have had the chance to do if you’d stayed in your comfort zone. Plus I’ve got some great stories for my memoirs.

What are the challenges and sacrifices of the vagabonding lifestyle? The most challenging part of this trip was travelling with kids. Travelling’s easier when you don’t have kids but if you have a dream you shouldn’t let being old, a parent or a business owner stop you from living that dream. I really want my kids to see the world to help them appreciate how lucky they are and see how many opportunities they have in life. Many times when we were in Central America I wondered why I’d swapped my lovely big house for cramped accommodation where the whole family slept in one room. Often we had no electricity or water and our car was a real jalopy – the roof rack fell off twice when we were driving along. We sacrificed comfort for adventure but to me that’s a great trade.

What lessons did you learn on the road? Be flexible in your habits and outlook. Everyone should learn this lesson and the best way to learn it and keep in practice is by travelling.

How did your personal definition of “vagabonding” develop over the course of the trip? There are always compromises and bad moments but if you can hit the road and travel at all then you’re winning.

If there was one thing you could have told yourself before the trip, what would it be? It was even harder with the kids than I thought but I’m glad I didn’t know that or I might not have gone.

Any advice or tips for someone hoping to embark on a similar adventure? Just do it. You have everything to gain and nothing to lose. I don’t want to have any regrets when I’m old and if you dream of travel there are so many ways to achieve it. I’ve lived and worked in Europe, North America, Central America, South East Asia, Australasia and Africa and travelled extensively around those areas. I’ve made travel a priority all my adult life but too often I hear people saying “I wish I could do it but…” and trotting out some lame excuse. Maybe they don’t really want to do it but if you really do you should. Life’s too short not to do the things we dream about now. Please don’t end up regretting things you didn’t do.

When and where do you think you’ll take your next long-term journey? We want to revisit Africa for a safari with the kids before they get to the stage where they don’t want to go on holiday with us any more. Three to six months in Kenya and Tanzania would be lovely with a trip to see the gorillas in a perfect world. But first we have to save up again and work hard to make it happen. I know it will, it’s just a question of when and how long was can get away for.

Read more about The Candy Family on their blog, Get In The Hot Spot or follow them on Facebook and Twitter.

Are you a Vagabonding reader planning, in the middle of, or returning from a journey? Would you like your travel blog or website to be featured on Vagabonding Case Studies? If so, drop us a line at [email protected] and tell us a little about yourself.

Image: Andi Campbell-Jones (flickr)

Original article can be found here: Vagabonding Case Study: The Candy family

August 13, 2015

Re-imagining college education with the Wayfinding Academy

Imagine a team full of change-makers led by a former University professor and consisting of others with a multitude of careers in higher education and educational, political, and media non-profit organizations.

Imagine them collaborating to create an alternative college that addresses a big problem in higher education: too many young people getting to college and not knowing why they are there, spending numerous years there accumulating massive debt, and arriving at graduation without knowing what is next for them.

“What do you want to do with your life?”

To address this these problems, this team has launched the Wayfinding Academy and at its center is the guiding question, “What do you want to do with your life?” The Wayfinding Academy will be an affordable, 2-year college based in Portland, Oregon focused on what matters most in education: real world experience, community support, and individual passion.

Students won’t be asked to choose a major from a list, they’ll be supported in discovering their own personal mission. They’ll take core classes building skills that will serve them on any path. And they’ll work with advisors to create handcrafted experiences meaningful to them and build a portfolio through real experiences, including travel, volunteer service, internships, and beyond. When a student graduates from the Wayfinding Academy, their advisors stick with them until they have a plan and execute their next steps, whether it be a four year degree, a year abroad, an apprenticeship, or a venture of their own.

In the spirit of bucking convention, this non-profit, start-up college is launching through a crowdfunding campaign in an effort to recruit friends as well as funds. The Wayfinding Academy is currently seeking to raise $200,000 on Indiegogo to fund the first year of operations until the first cohort of 24 students arrives in Fall of 2016. Funds raised from the campaign will enable the Wayfinding Academy to pay a few of their current volunteers to be staff, apply for regional accreditation, establish a scholarship fund for students, and prepare a learning space in Portland to receive students.

Let’s help the Wayfinding Academy launch and start serving students. Please visit the Indiegogo page to learn more and support the higher education revolution by making your tax-deductible contribution today.

Additional Information:

To see all the members of the team, visit the Our Team page on the Wayfinding Academy website.

To read recent articles, listen to interviews, or watch videos of the Wayfinding Academy founder, Dr. Michelle Jones, and her team, visit their Media page on their website.

Image: melis (shutterstock)

Original article can be found here: Re-imagining college education with the Wayfinding Academy

August 11, 2015

Solo female travel – right or wrong, dangerous or not?

I struggled down the narrow aisle of the rattletrap bus to my seat near the back, where the stench of gasoline permeated the air. Concerned that other passengers would not be able to get by, I stuffed my backpack on the floor behind my feet and my suitcase in the aisle next to me. I needn’t have worried. As the bus filled up, both were quickly buried beneath satchels, giant plastic shopping bags, and sacks of potatoes and onions.

A Quichua woman appeared at my side and directed her son to climb over me into the window seat. My delight that his small size would give me more room to move around turned to dismay when the woman also started to climb over me, and I realized that the three-hour trip up the steep Ecuadorian mountain would be made with three people crammed into a seat designed for two. When the young boy drifted off to sleep, I motioned for his mother to lay him down across both our laps, leaving both of us free to dive into plastic containers full of homemade food that other women were popping open and sharing around.

Barbara Weibel, solo female traveler, at Colca Canyon, Peru

This is the story I most often relate when people ask me why I travel solo. Had I been traveling with a companion, I would have been focused on that person, rather than tuning into a once-in-a-lifetime cultural experience. But while my love for solo travel was once seen as bravery, a couple of years ago people began questioning my decisions.

The furor over whether women should travel solo began in early 2013, soon after a New York woman was killed while traveling alone in Istanbul. A month later, the debate ratcheted up when six Spanish women were raped after attackers broke into their vacation bungalow in Acapulco, Mexico. By the time a young woman on a bus in rural India was raped by a gang of local youths (she later died), the discussion had disintegrated to near hysteria. Husbands said they would never allow their wives to travel alone. Parents were chastised for allowing their daughters to take a gap year of travel between graduation from university and entering the work world. As for me, people began accusing me of being foolish, and occasionally, downright irresponsible.

Had the argument been that no one should travel solo, I might have reacted differently, but the question became whether women should travel alone.

By this time, I’d been traveling full-time with no home base for more than four years, moving from country to country and earning a living through my travel blog, Hole in the Donut Cultural Travel. I’d been to more than 30 countries, including many in the developing world, and had never once had a problem or felt I was in danger. Had the argument been that no one should travel solo, I might have reacted differently, but the question became whether women should travel alone. Having spent my life in corporate America, fighting to get ahead in male dominated industries, this criticism seemed like just another way for men to “keep women in their place.”

It was telling that, whenever the issue of solo female travel was discussed, the word rape inevitably crept into the conversation. According to the U.S. Department of Justice’s National Crime Victimization Survey, an American is sexually assaulted once every 107 seconds in North America. In fact, according to a report published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime in 2010, North America ranks among the top three countries in the world for the number of rapes, assaults, and burglaries. By that measure, travelers are much safer in Europe, Australia, or Asia than they would be anywhere in North America.

Barbara Weibel, solo female traveler, at Elephant Nature Park in northern Thailand

Of course, bad things can happen, to anyone, anytime, so I take measures to be as safe as possible. I have observed countless situations where travelers do things that make them targets. They wear expensive jewelry, flash a lot of cash, get drunk or high in an unfamiliar environment, tell people where they’re staying, or leave with strangers without telling someone where they are going and when they will be back. In general, they do things they would never dream of doing if they were at home. In addition to refraining from this kind of behavior, I also do the following:

Check the windows of my hotel/hostel every night upon returning and before going to bed, to make sure they are still locked

Once at my destination, I stash my passport in a safe place and carry a only copy with me

Carry a backup debit card with a separate account number, in the event my main card is stolen or compromised

Never keep all my cash in one place

Carry limited cash and rely instead on ATM’s to get local currency after arriving in a foreign country

Scan all important documents (passport, driver’s license, medical insurance card, etc.) and email them to myself at an address where I can access them online (gmail, hotmail, Yahoo)

In countries where I don’t speak the language, I pick up a business card for the hotel/hostel, printed in the local language. That way, after a day of sightseeing, I simply hand it to a taxi driver.

When traveling on trains and buses, I never lose sight of my luggage, and I put my foot and leg through the strap of my backpack or purse when I set them on the floor (this is also good to do in restaurants – never hang your purse on the back of a chair)

Additionally, I have been known to lie outright about where I am staying, or to tell someone I am traveling with my husband, and that he will be joining me shortly. Perhaps most importantly, I pay attention to my gut. If something doesn’t feel right, I give myself permission to walk away, even if it means being rude. There are no guarantees in life, but by staying aware of what is happening around me at all times and following the rules I’ve developed, I feel just as safe in the countries I visit as I do in the U.S. It goes without saying that I’m not going to stop traveling solo, just because I’m a woman, nor do I think it is irresponsible or foolish to do so.

When Barbara Weibel realized she felt like the proverbial “hole in the donut” – solid on the outside but empty on the inside – she walked away from corporate life and set out to see the world. Read first-hand accounts of the places she visits and the people she meets on her blog, Hole in the Donut Cultural Travel. Follow her on Facebook or on Twitter (@holeinthedonut).

Image: David Jubert (flickr)

Original article can be found here: Solo female travel – right or wrong, dangerous or not?

August 6, 2015

Remembering the Hippie Trail

For independent travelers just now beginning to travel in Asia, the legendary overland “Hippie Trail” of the ’60s and ’70s is a natural source of fascination and envy. Unlike today’s Lonely Planet-toting backpackers, the counterculture wanderers of the hippie era pioneered their Asian routes by word-of-mouth and trial-and-error. Hence, in indie travel terms, Hippie Trail travelers are to present day backpackers what the Ancient Greeks were to the Ancient Romans: larger-than-life legends, who once wandered a wilder world.

For independent travelers just now beginning to travel in Asia, the legendary overland “Hippie Trail” of the ’60s and ’70s is a natural source of fascination and envy. Unlike today’s Lonely Planet-toting backpackers, the counterculture wanderers of the hippie era pioneered their Asian routes by word-of-mouth and trial-and-error. Hence, in indie travel terms, Hippie Trail travelers are to present day backpackers what the Ancient Greeks were to the Ancient Romans: larger-than-life legends, who once wandered a wilder world.

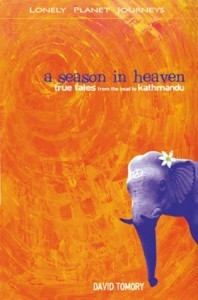

Legends can exaggerate, however — and that’s why it’s nice to have a book like David Tomory’s A Season in Heaven: True Tales from the Road to Kathmandu , an oral history that sheds a personal, realistic light on the Hippie Trail. In interviewing 35 people who once wandered the roads between Istanbul and Kathmandu, Tomory reveals the complexities within the travel culture of this era. After all, the Hippie Trail wasn’t the first independent travel phenomenon in modern Asia; it was the first mass independent travel phenomenon in modern Asia. And, like any mass movement, the Hippie Trail was defined as much by its reputation as its reality.

, an oral history that sheds a personal, realistic light on the Hippie Trail. In interviewing 35 people who once wandered the roads between Istanbul and Kathmandu, Tomory reveals the complexities within the travel culture of this era. After all, the Hippie Trail wasn’t the first independent travel phenomenon in modern Asia; it was the first mass independent travel phenomenon in modern Asia. And, like any mass movement, the Hippie Trail was defined as much by its reputation as its reality.

Thus, while hippie-era wanderers were creative, intrepid pioneers in a certain sense, they also tended to be petty, competitive, self-ghettoizing, and self-deluding. In short, they had the same charms and weaknesses as any self-conscious, authenticity-seeking counterculture movement of the last half-century — including the travel-hipsters of today. Behind the pretensions of the “movement”, however, were real travelers, having private, inspiring, life-changing experiences — and that’s what Tomory’s book best reveals.

Before I get into the narrative details of A Season in Heaven, I might point out that the book represents a purely Western-slanted look at the Hippie Trail. Asian locals at the time — while friendly enough — were not known to have been terribly impressed with hippie seekers: Indian writer Gita Mehta has referred to the Hippie Trail as “that long line of loonies”, and V.S. Naipaul wrote off hippie fascination with Hinduism as a “sentimental wallow”. Western expatriates and Asia-experts living along the Hippie Trail at the time were just as sardonic — and the New York Times had reported as early as 1968 that “Laos has grown disenchanted with the flower power folk, Thailand will not let them in without a haircut, and Japan now requires a bond of $250 as proof of financial stability.”

Thus, in interviewing only the Westerners who took part in the Hippie Trail, Tomory’s account is more of a nostalgic dialogue amongst middle-class travelers than it is a balanced social history of the movement. Still, it vividly captures the mindset of the young people who dropped all in the ’60s and ’70 to optimistically wander across Asia.

Much like travelers today, the motivation for Hippie Trail wanderers was the allure of exotic countries (Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal) and the opportunity to get away from the politicized environment of home. Unlike current travelers, there wasn’t much practical information available about Asia, or what to do when you got there. One of Tomory’s interview subjects journeyed off from England under the impression that in India “you could live in the forest, eat berries, meditate in a cave, wander around naked or do whatever you felt like and nobody would take a blind bit of notice because everyone innately understood what you were doing.” With expectations like this, it’s no wonder that the people of India were baffled and bewildered by their young Western guests.

Though the quest for Eastern spirituality is a big part of the Hippie Trail myth, Tomory writes that the movement was more about seeking freedom from the moral and social restraints of home. True to the rock-n-roll ethos of the time, the presumed availability of sex and drugs in Asia was a big travel motivation — and this naturally lent to the hipster allure. “It you were really hip — it was like being the first to wear a minidress — you went to India,” recalls one German interviewee.

With the hipster reputation, of course, came hipster pretensions. “In Kabul you saw all the people on their way back from India,” reports traveler Carmel Lyons. “The fashion was prayer shawls, the whole look, pyjamas and beads and drifting fabrics and waistcoats and bare feet and harem pants. And god, they were arrogant.”

The root of arrogance, it seems, was often money — the lack of which was seen as a sign of true travel experience and virtue. Naturally, this attitude ignored the fact that relative economic prosperity in the West was what enabled all those temporarily jobless young people to travel in the first place. Thus, Tomory notes, the Hippie Trail travelers who had money pretended not to, and legends abounded as to how cheaply one could wander across Asia. One storied Englishman is said to have hitched from Damascus to Delhi on just $6. In theory this was indeed a remarkable feat, though it infers that people happily exploited Asian hospitality in order to facilitate subcultural pissing contests. (After all, that storied hitchhiker could well have stayed an extra month in England washing dishes and traveled from Damascus to Delhi in a way that benefited local bus drivers and restaurant owners).

At the root of this traveler onedownsmanship lurked the fact that Hippie Trail travel was unavoidably difficult; dangers and sickness abounded (“Ah, Kabul,” one traveler remembers people bragging, “that’s where you found the real dysentery”). Unlike the travelers of today, travelers had to carry all their cash with them at once, and they often languished for months in flophouse hotels waiting for money transfers to come through. News from home was hard to come by, and travelers’ families often gave them up for dead (at times — far more often then than now — travelers did wind up dead). According to one of Tomory’s respondents, travelers had to contend with “traffic accidents, robbers, corrupt officials, bisexual rapists, filthy quarantine camps, Russian cholera vaccine, loss of sanity and, of course, their own penury.”

By comparison, today’s travelers — warned, wired, and ATM-ready — have it easy. Still, it would be an exaggeration to say (as many veterans of the era do) that the hippie epoch was peopled by purer, nobler travelers than we see today. Like present-day backpackers, Hippie Trail wanderers frequently stuck to traveler ghettos — often the same hotels in the same cities: Gulhane or Yener’s in Istanbul; Amir Kabir in Teheran; the whatsisname in Kabul; the Crown in Delhi; the Modern Lodge in Calcutta; the Matchbox and the Hotchpotch in Kathmandu. “Every city of the route had a budget foreigner quarter,” writes Tomory, “and everyone passed [hotel] names to everyone else.” Indeed, as exotic as the scenery was, the Hippie Trail was often a static succession of dorms, drugs, and familiar faces.

Moreover Asia may not have been in the grips of globalization during the ’60s and ’70s — but there is ample evidence that the young travelers of that era were the ones who first introduced it. By the early seventies, Bollywood had produced a hippie-themed Indian musical called Hare Krishna, Hare Rama, and travelers were reporting Jimi Hendrix-style Afro wigs for sale in the furrier’s market of Kabul. (And, for all the disdain heaped upon the pizza-n-burger menus of today’s Asian guesthouses, the anomaly of Western food in Eastern settings may well trace its origin to the likes of Siggi’s Restaurant in Kabul, which served schnitzel and potato salad for homesick hippie palates.)

Ultimately, then, Tomory’s book reveals that the Hippie Trail was not the stuff of legends, but of normal, curious, intrepid people who were making do within the travel conditions of their time. Asia has certainly changed a lot in the years since then — as has the technology that helps us travel there — but the discoveries it offers are still found on a personal level, apart from the labels that attempt to define the experience.

Image: Patrick (flickr)

Original article can be found here: Remembering the Hippie Trail

August 4, 2015

Review on Tortuga Backpacks’ daypack

Our flat-bottomed boat hit another large ocean swell. I was hung onto the seats in front of me, my knees cushioning each bone-shattering impact.

The boat was air-borne for a split second. I was flying, anchored only by my white-knuckled hands gripping the seats.

The boat hit the bottom of the next swell flat-on and rocked. Overhead waves splashed the boat’s clear plastic roof.

A second later, the boat was air-borne again, face-planted into the next wave, tossed water over its bow and kept plowing through the ocean.

This was Vancouver’s bay. Seeking the whale pod reportedly dancing on the imaginary line between Canada and United States, the boat’s bow sliced towards the open Pacific ocean.

At my knees, a small black daypack bounced, held to the seat by a small loop. With every brain-shaking impact, the daypack leaped into the air and slammed its weight against the loop as the boat fell back to the ocean.

The team at Tortuga Backpacks was kind enough to send me their new daypack to try out. So I brought it on my three-day trip to Vancouver.

Welcome to my real world travel gear test of Tortuga Backpacks’ daypack.

Overview of daypack

Tortuga Backpacks’ daypack is a 20L black collapsible backpack that has its own storage pouch built in. When you’re not using it, stuff it into its little pouch. When you need it, pull it out of the pouch and use it.

This daypack boasts an inside organizer panel, a large main compartment, large mesh front pocket large enough for a jacket, a small top pouch that doubles as the daypack storage pouch and a handy stashing place for your wallet and sunglasses when the daypack is in use. Two side mesh pockets easily fit a large water bottle.

Inside is a laptop sleeve (for a 15″ laptop) with minimal protection. This daypack is not designed to carry your laptop through airport jungles, just to bring it to the cafe around the corner to plug into WiFi and work.

Size

Since it’s a daypack, there’s two factors in size:

Size when unfolded and used as daypack;

Size when folded into its pouch for transportation.

1) Size when daypack

20L is a lot of space. And I swear, Tortuga Backpacks has struck a deal with the space-saving gods. Whenever I thought this daypack was full, I’d stuff something else in and it’d fit.

At the end of one day of walking around Vancouver, here’s what my daypack held:

At the end of one day of walking around Vancouver, here’s what my daypack held:

Three water bottles

Four apples

Two bars of soap

Bag of carrots

Wallet

Two pairs of glasses with one case

Two sandwiches

Two small to-go containers

Two energy bars

Four bananas

Hat

One smartphone

2) Size when in pouch

It’s the size of a paperback book, only more flexible so you can shove it into small spaces. Toss it into your bag on top of your clothes and you’re good to go.

Comfort

The real question: how does this daypack feel on your back?

Daypacks are notoriously flimsy and not designed with comforts like padded backs or straps. They are designed primarily to fold up into tiny little bundles then shake out into carrying bags.

Tortuga Backpacks changed that.

This daypack has a padded back that even allows air flow for sweaty spines. True, the padding is minimal, but it’s contoured for comfort and some padding is heaps better than nothing. A chest-strap evens out the load.

Photo courtesy of Tortuga Backpacks

I wore this daypack for three days straight walking around Vancouver. Most of the time it was jammed full of water bottles or fruit. Never once did my back or shoulders complain about the weight.

Toughness factor

Let’s be honest here: I need my travel gear to hold up to my adventures. The last thing I want is a strap to break, seam to rip out, or zipper fall apart. What I need is tough.

Here’s what I put this daypack through:

7 hour boat ride through choppy seas where full daypack bounced against loop;

3 full days of walking in rain or drizzle with daypack loaded with water, fruit, snacks and mementos;

6 hour train ride with daypack holding two full-size takeout containers filled with food and zipper straining to stay shut.

How did it stand up?

It looked like I hadn’t just beaten it for three days straight. Even though Tortuga Backpacks doesn’t claim this daypack is waterproof or water-resistant, it is. After walking under the Northwest’s weeping skies, my stuff inside never got damp.

Final word

Will I be retiring my leather messenger bag on trips for Tortuga Backpacks’ daypack? Probably yes on those longer trips where lots of walking and carrying is involved. After a long day of carrying a messenger bag’s weight on one shoulder, I ache.

But I never had a backache in Vancouver with this daypack. And it’s super nice to not jam your bag under your jacket every time it starts to rain.

Tortuga Backpacks’ daypack is available for pre-order here and costs $54.

Laura Lopuch has gypsy-blood running through her veins and writes at Waiting To Be Read where she helps you find your next awesome book to read.

Image: Jason Priem (flickr)

Original article can be found here: Review on Tortuga Backpacks’ daypack

July 30, 2015

Vagabonding Case Study: Christophe Cappon

Christophe Cappon of Thailand Yoga Holidays Blog

Age: 30

Hometown: Toronto

Your favorite quote: “Not all those who wander are lost” – J.R.R Tolkien

How did you find out about Vagabonding, and how did you find it useful before and during the trip? I kind of just fell into it. Once I left home the desire to continue traveling and seeing new places didn’t go away so I found ways to make it work longterm.

How long were you on the road?

I left Toronto when I was 19 and I’m now 30, so 11 years on the road and counting!

Where did you go?

My first move away from home was to attend Trent University, a small university two hours from Toronto. From there I just kept going further soon making a big leap over to India and Asia – I haven’t looked back since.

What was your job or source of travel funding for this journey?

Since I was 12, every winter I shovelled snow from the sidewalks and every summer I mowed lawns. I always felt I needed to save up – even if I didn’t know what for. By the time I turned 19, I was ready to go! I didn’t expect to constantly be travelling and living abroad but things have a funny way of working out and since my work, travel and personal life have all become intertwined.

Did you work or volunteer on the road?

After completing my TESOL training in Canada, my first international job was teaching English in Yangshuo – a small, scenic village in central China. However, before that I got some practice as a volunteer teaching English to Tibetan Refugees in Dharamshala, India. At the beginning of my travels I also started my yoga teacher training and going down the path of becoming an independent instructor. I now have been teaching yoga in my home base of Chiang Mai, Thailand and around the world for the past eight years. I just recently established my own business, Thailand Yoga Holidays, fusing my love for travel, yoga and Thailand, so working “on the road” has become my life!

Of all the places you visited, which was your favorite?

I’ve always loved Thailand – as much for the delicious food and warm climate as the friendly people and vibrant yoga community. Unlike most people who head there for a quick dose of sea and sun, I went to Chiang Mai as an exchange student studying International Development and Indigenous Culture. I lived with a Thai host family for the year and quickly learnt the language in addition to gaining invaluable insight into local culture. Since then, I went on to study yoga – both in Thailand and across the globe – until I founded Thailand Yoga Holidays In any case, it is thanks to my first experience here that I was then able to understand the culture, discover its secrets and it is surely the reason why I am still here.

Was there a place that was your least favorite, or most disappointing, or most challenging?

Despite an unforgettable trek in the Sahara, Morocco was my most challenging as I could never get used to the incessant touts and scams.

Which travel gear proved most useful? Least useful?

Most useful : travel towel, Swiss Army knife and headlamp

Least useful : malaria pills – you always think they’ll be good to have, but then never end up taking them

What are the rewards of the vagabonding lifestyle?

The best part is the freedom : to go where you want, when you want.

What are the challenges and sacrifices of the vagabonding lifestyle?

In a transient lifestyle, the most challenging has always been cultivating longterm relationships. You’re always meeting new people…and saying goodbye to them just as quickly. However, the upside is that there’s never a dull moment as you’re constantly get to meeting different people and participating in new experiences – it’s addicting.

What lessons did you learn on the road?

When travelling, there are always ups and downs. Sometimes things go your way and sometimes your plan completely backfires. In those times, it’s important to remember to go with the flow – it’ll make your vagabonding a lot smoother.

How did your personal definition of “vagabonding” develop over the course of the trip?

At first, vagabonding was just a way of seeing the world while spending the least amount of money – because the more money I could save, the longer I could travel. Eventually, I realized this system could only last so long. That’s when I began offering yoga retreats in Thailand. It was a no brainer : live in an amazing country, do what I love and make people happy!

If there was one thing you could have told yourself before the trip, what would it be?

Don’t put off registering for a frequent flyer program. It’s totally worth it!

Any advice or tips for someone hoping to embark on a similar adventure?

Go with your gut, follow your dream and don’t give up. There’s a whole world of wonderful possibilities waiting for you out there.

When and where do you think you’ll take your next long-term journey?

I’ve always wanted to discover Burma as I hear it’s like Thailand was 50 years ago. It’s also well known for its monasteries and meditation centres. I am always looking for exciting, unique experiences to discover and share with others. Who knows, maybe I’ll start bringing people to Burma for yoga holidays as well!

Read more about Christophe on his blog, Thailand Yoga Holidays or follow him on Facebook and Instagram.

Are you a Vagabonding reader planning, in the middle of, or returning from a journey? Would you like your travel blog or website to be featured on Vagabonding Case Studies? If so, drop us a line at [email protected] and tell us a little about yourself.

Image: Andi Campbell-Jones (flickr)

Original article can be found here: Vagabonding Case Study: Christophe Cappon

Rolf Potts's Blog

- Rolf Potts's profile

- 321 followers