Kiese Laymon's Blog, page 2

October 14, 2013

The Fake Male Feminist Chicanery by Minh Nguyen

Some personal thoughts on this wily breed …

Some personal thoughts on this wily breed …

This last summer, a straight male friend and I cozied up on his sofa with his laptop and, to sate my nosiness, perused his OkCupid account. My friend received a graduate degree in gender studies and is intimidatingly informed about both theoretical and pop feminism, which was invariably conveyed on his dating profile. In his inbox, women responded positively to his profile’s reference of the ”manic pixie dream girl” trope (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uqJUxqkcnKA). “I’m just so glad you know about that,” they lauded. “It’s so refreshing to see a guy get it.” Their receptiveness made sense. In the online dating mineshaft, my friend–who not only appeared sane and had photo proof that he goes outdoors, but also displayed some awareness of feminism(!)–was a glitter-dipped gemstone. I was struck with revelation. Of course. The male feminist card gets you play.

Flash back a year, and I’m cozy on my own sofa with my own laptop, watching a video in which social commentator Jay Smooth speaks out (http://vimeo.com/44117178) about the Anita Sarkeesian controversy. In his video response to the violent and threatening reactions from men toward Sarkeesian’s criticisms of gaming culture’s hostility toward women, Smooth rebukes not only the offenders but also those who turn the other cheek, asserting that “we need to treat [this kind of abuse and harassment] like it matters”. His demand to his “fellow dudes”: “When [we] see something like that going on, [we] have an obligation to speak out against it more often.”

In a different tab on my browser, I’d pulled up an interview with novelist Junot Diaz, whose The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao I was engrossed with at the time. In this interview (http://www.salon.com/2012/07/02/the_search_for_decolonial_love/), Diaz discloses that despite the criticism many women writers of color received from men of color in the 80s, he himself feels a certain indebtedness to the women writers for creating “a set of strategies” that would become “the basis of [his] art.” Diaz goes on to state that “what [these women writers of color] were producing in knowledge was something that I needed to hear in order to understand myself in the world, and that no one—least of all male writers of color—should be trying to silence.”

Here I witnessed two men behaving in what to me were very radical and admirable ways, defending women who had received sexist backlash from other men. I rarely saw straight men raise a skeptical brow at sexism, much less spoke out against it to other men. Like many others of their audience, I felt affirmed, supported, and grateful to have them as advocates. I felt full of conviction. These are real men. These men are how all men should be.

If you frequent the same nook of media as I do, it’s likely you know and love these men, too. Salon crowned Jay Smooth as one of the sexiest men of 2008, and between my circles and what I’ve observed on his Twitter and Instagram, there appears to be plenty of those open to the prospect of being “Mrs. Jay Smooth”. Junot Diaz, although more controversial, has also received praise for his feminist-oriented writing, and at the Facing Race conference in 2012 where Diaz spoke the keynote, the first (and second) question of his Q & A was an emboldened “Are you single?” These male feminists get a lot of love in the minds and hearts of straight women. We love them, and not in the way we love our Uncle Rays.

While they both are replete with admirable qualities, being outspokenly pro-woman is a giant, glossy cherry. They, too, are diamonds in a mineshaft. When most men I encounter at bars, on television, and in the news make remarks about women that make my insides feel grimy, a man who attempts to veer off the sexist path will lower my guard. Of course I greet the change of pace with relief, ease, and even a bit of sexual attraction.

Back then I would read and watch Smooth and Diaz, wish to the plush stuff above that more men would be like them, then close my laptop, leave my apartment, and in my own small life, meet, become intimate with, and perpetually get bamboozled by disingenuous men. During my last year of undergrad, as I upheld Smooth and Diaz as acmes of good men, I would meet a man who led a feminism reading group and become involved with the women, pissing them off to vision-blurring rage. I would meet a man who writes his thesis on Audre Lorde’s idea of a lesbian consciousness but was always the last to leave a party, eyes darting around for inebriated women, prospective bedmates. I would meet countless self-proclaimed feminists whose mouths would ask, “Have you read Gender Troubles?” while their body language asks, “Is that the passcode to your pants?” And I would pardon these men over and over again, because they behaved, at least initially, like my male feminist role models. They, too, presented themselves as advocates for women, and they, too, all sounded like I thought “anti-sexist” men should sound.

As I observe the public appraisal of two men I don’t know and the bad behavior of the men I do, I can’t help but make loose connections between the two. The men I know who behave disingenuously, the nominal feminists, seem to have had their acts reinforced somehow. And I worry that the appraisal of men who can articulate a feminist critique begets scheming imitators, men who file “feminist” in their rolodex of pick-up artistry because they’ve seen it result positively. Lack game? Try this formula: mention x feminist theorist, y lamentation about political issue that attacks women’s rights, z assertion about sexual consent. That tactic alone may work on someone, and that’s utterly scary.

I attended a large university in Seattle, and one drawback of being surrounded by educated and well-read people is that, if there’s a benefit, they can be magicians with language, chameleons about who they are through the use of words. With issues as intimate as dating and feminism, it’s not only ironic to be deceived by empty sentiments of anti-sexism, it’s dangerous. What troubles me is that for many women I know, sexual assault and date rape remain a common experience, despite “male feminism” becoming more fashionable over the years.

In my ideal world, the misogynists would be ultra-detectable, with facial pocks and sulfury odors and grunt “wiggle your glazed donut ass for me.” I would even take the world as I thought it a few years ago, where misogynists talk like Tucker Max and live in Greek houses and call women “biddies.” But confusingly, misogynists are sometimes men who speak softly and eat vegan and say “a woman’s sexual freedom is an essential component to her liberation. So come here.” It’s a tricky world out there. And while I’d prefer a critical approach to gender from men I elect, read, and even bed, in my experience, the so-called feminist men I’ve met deep down have not been less antagonistic or bigoted toward women. What I see over and over again is misogyny in sheep’s clothing, and at this point, I would rather see wolves as wolves.

Given the dearth of men who acknowledge, much less pretend to care about, sexism, my words may seem as salty as twice-brined pickles. But as my friends and I joke, we don’t have to be grateful for the crumbs of lazy and fraudulent feminism men give us. And in seriousness, I don’t want to get duped anymore. I don’t want to let my guard down in the company of a man who received a graduate degree in gender studies, deny his sexual advances, and hear from a mutual friend about how angry and baffled he was at my refusal, because he was “expecting it.” I no longer want this sort of surprise-in-hindsight, but I also don’t want to relinquish all hope, and that is going to require extreme critical flexing toward so-called straight male allies.

My wish to the plush stuff above is no longer for men to imitate Smooth and Diaz on a cursory level, but to make efforts toward more personal reflections of sexism without ulterior motives of appearing more desirable to women. My revised wish, as well, is for me and other women seeking relationships with men to get better at detecting and calling out insincere male feminism, discourage and endanger it, rather than allowing it to continue to flourish through positive reinforcement. My wish is that when we do let our guards down again, that we will be safe in doing so.

Minh Nguyen is a miniature quiet storm brewing in Seattle, WA. Write her at [email protected].

October 3, 2013

Bloodletting Season — by Vanessa Willoughby

In order to survive adolescence, you must force yourself to sell-out. Bite down on your tongue, harden your jaw, clench your teeth, and learn to join the league of the invisible minority. Trick your white classmates; they must not realize that you’ve infiltrated their tight-knit ranks. Learn to take history as gospel, never look beyond the pages. Act as the sole representation of your race. Heavy is the head that wears the crown. You are like the cockroach in Audra Lorde’s poem; you may be detested and despised, but you cannot be killed.

In order to survive adolescence, you must force yourself to sell-out. Bite down on your tongue, harden your jaw, clench your teeth, and learn to join the league of the invisible minority. Trick your white classmates; they must not realize that you’ve infiltrated their tight-knit ranks. Learn to take history as gospel, never look beyond the pages. Act as the sole representation of your race. Heavy is the head that wears the crown. You are like the cockroach in Audra Lorde’s poem; you may be detested and despised, but you cannot be killed.

**

You’re not like other black people.

You sound white.

Are you a mulatto?

Is your hair real? Can I touch it?

You’re black; you must know how to dance!

Where are you from? No, really, where are you from?

I want to have mulatto babies!

But you didn’t grow up in a ghetto, so you’re not really black.

But he didn’t MEAN to be racist….

I wish black people would stop talking about racism.

What are you?

You’re ugly.

The fact that these sentiments flowed from the mouths of both friends and foes alike makes you feel very, very small and useless and naïve and you wish that you had clung to your dignity with the ironclad determination of a captain about to sink with his beloved ship.

Your identity was never fully yours. They claimed it and twisted it and warped it and defaced it like the crypt robbers who ransacked the Egyptian tombs. You refused to accept the realities of double-speak, of coded-language, of words that harbored mild apathy to condescending disdain. They tried to make you crazy, to convince you that you were shadowboxing. At first, it was much easier to submit, to slip into your token role, to open your mouth, take on water and drown. Your mother moved through life like an eel, maneuvering through society with the flash of white teeth and a slickness only known to outsiders who have served so long as a punching bag that they are numb to the onslaught of brass-knuckled blows. On the other hand, your father was not afraid to tell you what it meant to be black in this version of America, this vision constructed from the indulgence of privilege, what it meant to be a member of a race of people whose skin color came with baggage, a history that was simultaneously American and “Other.”

Railing against your rationale, you carved these banners of ignorance between the inner cracks and crevices of your subconscious, absorbed the toxins like ink into your skin, tried to acquire the same kind of blindness that they professed as moral hymns. At times, living in a staggering display of whiteness heightened your depression. The authenticity of your identity was dependent upon an adherence to stereotypes. When you were twelve, you composed a life plan which would begin when and not if you escaped to New York City. You now realize that you were confused all those years because you were looking to fit into a crowd that would rather hoard and eat your culture and spit you back out until you were nothing but bones picked-clean.

You were not searching for tolerance, but unequivocal equality.

You are so tired of being the token minority, the stand-in for the exotic and strange. You are tired of trying to educate and explain to deaf ears. You are tired of expecting compassion and receiving indifference. You are tired of being a pillar of indomitable strength for people who do not have strength of their own.

You are tired of the world’s definitions.

**

Bloodletting is an ancient medical procedure that was commonly practiced in order to cleanse the afflicted body of the illness—or rather the evil spirit that had attacked the patient. According to PBS, “bloodletting [has a] 3,000 year history [and] began with the Egyptians of the River Nile one thousand years B.C., and the tradition spread to the Greeks and Romans.”

Some people will keep friends, no matter how broken the relationship, no matter how tired the loyalties, because they need to be lost in a crowd to feel secure. Some people will keep friends that are toxic because they afraid to be alone. They are convinced that being alone is synonymous with loneliness. Some people will honor the ghost of childhood friendships past because alliances cemented in early adolescence carry a weight that mimics the intensity of a life debt. These people have stuck by you through your growing pains, through the awkward fumbling towards adulthood. But does such allegiance matter when these friends view you as a non-threatening exception to their stereotypes? Does it matter when your friendship is an excuse to assuage white guilt? To consent to the powerless role of the model minority?

In order to cure the soul, you must let the bloodletting begin.

Vanessa Willoughby is a graduate of The New School

July 22, 2013

George Zimmerman, White Supremacy and Black and Brown Criminality: It’s Much More than Racism — by Gyasi Ross

I wish George Zimmerman was simply a racist. I wish I could say that he was a white redneck that hated brown-skinned people. If he were, then the shooting of Trayvon Martin would be explainable. It would still be tragic and wrong and heartbreaking, but at least it would fit into historical terms that we could understand: “racist,” “white person,” “black person,” “gun,” “fear” and “tragic death.”

I wish George Zimmerman was simply a racist. I wish I could say that he was a white redneck that hated brown-skinned people. If he were, then the shooting of Trayvon Martin would be explainable. It would still be tragic and wrong and heartbreaking, but at least it would fit into historical terms that we could understand: “racist,” “white person,” “black person,” “gun,” “fear” and “tragic death.”

But he’s not white, and he’s not a racist.

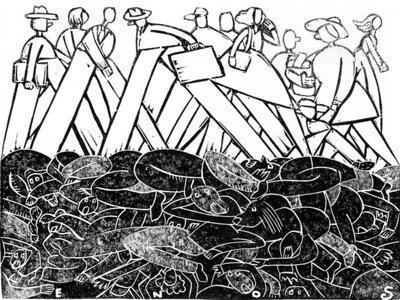

Zimmerman was the perpetrator of this awful crime. Horrible. And as evil as that crime was, it would feel good to be able to demonize him and pretend that he is an aberration. But he is not unique—in fact, he is very typical in this Nation. As much as I’ve seen the memes and facebook posts that “We Are All Trayvon,” I think that we are also likewise “All George Zimmerman.” That is, much like pretty much every person in this Nation of all colors, he is a by-product of a culture that criminalizes all brown and black males. That’s not racist—it’s bigger than mere racism. It’s almost a universal presumption that every American holds, whether brown, white, black, yellow or red. That’s what makes this case—and many, many others like it—so vexing, because it pretty much guarantees that other cases like it will happen again.

It’s almost innate in America.

George Zimmerman is not unique—his paranoia, his fear of brown and black people has been echoed many times by people of all color. Bernard Goetz had that fear. Sarah Page had that same fear. Ian Birk had that fear. But it’s not just white people—Hispanic people like George Zimmermen have it. The murderers of massive amounts of young black men whose trials are not on CNN and MSNBC because they are killed by other young black men—are have that same fear. So they act and kill—not racist, but in accordance with white supremacy. I’m informed by Chris Rock’s piece “Niggas vs. Black People” on his 1996 CD “Bring the Pain.”

“(People say) It isn’t us, it’s the media. The media has distorted our image to make us look bad.” … Please. … When I go to the money machine at night, I’m not looking over my shoulder for the media. I’m looking for niggers.”

Even Reverend Jesse Jackson, a civil rights activist, who probably has every incentive not to admit that he is paranoid about brown and black men, displays the same fear:

“There is nothing more painful to me at this stage in my life than to walk down the street and hear footsteps and start thinking about robbery. Then look around and see somebody white and feel relieved…. After all we have been through. Just to think we can’t walk down our own streets, how humiliating.”

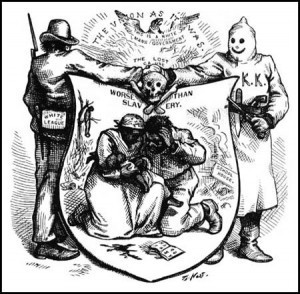

I repeat: this tendency is not racist. It’s bigger than racism. It cannot be racist unless we are willing to accept the premise that people of color—the same folks who scholars such as Professor Michael Eric Dyson says cannot be racist because racism “presupposes an ability to control a significant segment of the population economically, socially and politically by imposing law, covenant and restriction on lives”—are just as capable of racism as white people (as evidenced by the quotes above). No, instead this fear is a symptom of something much larger than mere racism—white supremacy. That is, this fear of brown and black males shows that even we, people of color, believe that the morals and social norms of white people are more controllable and civil than our own. As a result, we have an easier time believing that those that look like us—brown and black males—are more inclined to engage in criminal behavior.

And it begs the question: If we carry that presumption about our own selves and neighbors, how do we expect the white people that do not see or interact with brown and black males every day to see us?

I think of two specific examples from my own life that illuminated this for me—of course the consequences weren’t nearly as tragic as the instant Trayvon Martin tragedy. Still, they showed me that we’re all just as brainwashed, as fearful as George Zimmerman and Chris Rock and Jesse Jackson to believe that young men of color—specifically brown and black men—are predestined to be criminals. We’re all victims and believers in a disgusting and insidious type of non-racist white supremacy. In both of these instances I believe honestly that the folks involved are not racists—they’re just victims of this belief that permeates all levels of Americans.

The first was when I was 15. When I was younger, most of the people around me thought that I was Samoan—long, curly hair, big and brown. As a result of that (and also because I played football in school), I always had a lot of Samoan friends—that was good, because Samoans were the kids you didn’t want to piss off. Now, I was always a “square”—I didn’t drink, didn’t smoke, hell, I barely ever cursed. A good kid. One time, there was a fight at my school and evidently there was word that a Samoan kid was involved. Immediately, the black security-type (I don’t know his official job title) literally gathered up all the Polynesian kids—Samoan or not—and me and kinda quarantined us to this small area Japanese internment camp-style because, apparently, we were about to riot. Now, I didn’t even know about the fight—I’m still not sure that there was one. Still, we were presumed violent immediately—even those of us who are not Samoan—and made to feel like criminals in a setting (school) that was supposed be a slight respite from the ugly realities of the real world.

The second came when I finished law school and moved back to Seattle. I was getting  ready to have my first jury trial after whupping the prosecutors in bench trials for several months. Like any big endeavor for me, I planned to visualize the whole process: me being victorious, where I would walk, the questions I would ask, etc. Therefore, I went to the courtroom where the trial was to happen; I wanted to scope out the space. I was fly, feeling super-duper Ivy League that day—conservative, no earrings, hair back in a bun, new suit, new socks, even new underwear so I could feel supremely confident and wow my jurors. Sitting at the defense table, practicing my posture a little white lady comes in and looks surprised to see me there. She smiles at me and says, “Are you waiting for your attorney?”

ready to have my first jury trial after whupping the prosecutors in bench trials for several months. Like any big endeavor for me, I planned to visualize the whole process: me being victorious, where I would walk, the questions I would ask, etc. Therefore, I went to the courtroom where the trial was to happen; I wanted to scope out the space. I was fly, feeling super-duper Ivy League that day—conservative, no earrings, hair back in a bun, new suit, new socks, even new underwear so I could feel supremely confident and wow my jurors. Sitting at the defense table, practicing my posture a little white lady comes in and looks surprised to see me there. She smiles at me and says, “Are you waiting for your attorney?”

I don’t think these were racist acts. I think they are acts that show how deeply ingrained white supremacy is into all of our psyches. Just like I don’t think George Zimmerman’s act was racist. Just like I don’t think that the defense effectively putting Trayvon Martin on trial during George Zimmerman’s trial was racist. Just like I don’t think that the jury finding George Zimmerman “not guilty” was racist. I think it’s simply residue from this horrible thing—white supremacy, that believes that men of color must be doing something wrong at all times—and that’s what scares me.

That residue is not going anyplace anytime soon—it’s been here for 500 years. A guilty verdict would not have changed that; a guilty verdict would have felt slightly better, but it would not change anything about the larger problem—white supremacy. I’m not sure, honestly, what will.

God bless Trayvon Martin’s family and give them comfort.

Gyasi Ross is a member of the Blackfeet Nation and his family also comes from the Suquamish Nation. He is a father, an activist, an author, and an attorney. He publishes other people’s writings at cutbankcreekpress.com, makes videos at www.youtube.com/rockpaperjet, and writes a regular column at www.indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com. His twitter handle is @BigIndianGyas

July 21, 2013

An Echo’s Punctuation: A Letter to Four Brothers From Ádìsá Àjàmú

A few months ago, while putting the final touches on the book, How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, I realized that there were two voices I needed to make the project complete. One voice was my Grandmother, Catherine Coleman, and the other was the voice of Ádìsá Àjàmú. When I talked with my Grandmother about the project, she reminded me that her spirit and voice are literally in every piece in the book. “Don’t force it,” she told me. “Just let every voice in the book breathe.”

In “Echo,”

the anchoring piece in the book, Mychal Denzel Smith, Darnell Moore, Kai Green, Marlon Peterson, and me write to each other, exploring the need for black boys of this nation to seize breath, memory, honesty and transformative will. The piece is absolutely stunning. But it needed Ádìsá Àjàmú, the most generously genius and loving writer I’ve read in over a decade. I gave our piece to Ádìsá’ and asked him to add his letter to the mix. Sadly, the book was already on its way to the printer when I got his incredible offering. When, or if, you read the “Echo” piece in How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, come back here and read Ádìsá’s absolutely stunning punctuation. We are so lucky to call this beautiful man our brother.

A few months ago, while putting the final touches on the book, How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, I realized that there were two voices I needed to make the project complete. One voice was my Grandmother, Catherine Coleman, and the other was the voice of Ádìsá Àjàmú. When I talked with my Grandmother about the project, she reminded me that her spirit and voice are literally in every piece in the book. “Don’t force it,” she told me. “Just let every voice in the book breathe.”

In “Echo,”

the anchoring piece in the book, Mychal Denzel Smith, Darnell Moore, Kai Green, Marlon Peterson, and me write to each other, exploring the need for black boys of this nation to seize breath, memory, honesty and transformative will. The piece is absolutely stunning. But it needed Ádìsá Àjàmú, the most generously genius and loving writer I’ve read in over a decade. I gave our piece to Ádìsá’ and asked him to add his letter to the mix. Sadly, the book was already on its way to the printer when I got his incredible offering. When, or if, you read the “Echo” piece in How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, come back here and read Ádìsá’s absolutely stunning punctuation. We are so lucky to call this beautiful man our brother.

———————————————————————————————————-

Dear Mychal, Darnell, Kiese, Kai and Marlon—Yimhotep, brothers:

Thank you for your candor, for being courageous enough to stand in the heat and not attempting to cool pose, and for showing the sinew of pain that so often lies beneath the sheath of smiles. As you all know deep hurt sometimes explains us but we remain victorious so long as we refuse to let it define us.

Love and loss, so much of life is lived in the (heart)beats and (heart)breaks between the tumultuous and giving beauty of those two kinds of experiences. While anyone who has ever loved can certainly agree that love has a tumultuous and giving beauty. It must seem, on the surface, like a paradox to suggest to you brothers that loss also has its moments of giving beauty; especially with the kinds of loss you have all endured personally, and kinds and quality of losses we have endured collectively as a people. But loss sometimes does give even if it introduces itself initially as a painful absence. I know you must be thinking, “This brother must be smokin’ dat ‘good-good.’” Before I attempt to convince you that I’m not channeling Smokey from Friday, I suppose I should share a little bit about me.

I was born in a small African village located in an eastern city just off the Atlantic coast of North America called the Bronx. I can’t say that my childhood was idyllic but it certainly didn’t resemble the “bleak childhood fantasy” Baldwin experienced. And I would certainly relive it again. As a child growing up in the 1970s, the Boogie Down was a dangerously magical place. Life was structured around stoops and bodegas, play and penny candies, stickball, basketball and games like Ringolevio and Hot Beans and Butter, which were our national pastimes. We were multicultural before white folks forced us to use a word to say what we already knew: that “human” didn’t mean just mean alabaster with rushes of pink.

There was always one Black person whom you played with and whom you just knew was Black like you (of the Negrus Americanus variety) and then one day you heard his mom call him in a language you didn’t know—Puerto Rican or Dominican Spanish—and then he would look at you like he was a part of a spy ring and his cover had just been blown, and you would look at him with that look that said without actually saying the Richard Pryor line: “ What kinda n*gga is you?” Eventually there would be some other dude the two of you played ball with and his mother would call him too but in language that sounded eerily like English but usually was accompanied with some elegant phrase like Bumboclot, which had you and your Puerto Rican or Dominican friend (of the Negrus latinus americanus variety) looking at him with that same, “What kinda n*gga is you?” look.

We played often and sometimes we fought; everyone thought they could scrap until the Jamaicans—we called them West Indians—changed the game with a strange new weapon—the headbutt. In the world of knuckle up street fighting, that joint was the equivalent of the atomic bomb. Needless to say there weren’t many fights with the Jamaican dudes. I still think they were the reason that guns became the weapon of choice in the South Bronx because once a n*gga headbutted you, you really had few actionable comeback options.

We played often and sometimes we fought; everyone thought they could scrap until the Jamaicans—we called them West Indians—changed the game with a strange new weapon—the headbutt. In the world of knuckle up street fighting, that joint was the equivalent of the atomic bomb. Needless to say there weren’t many fights with the Jamaican dudes. I still think they were the reason that guns became the weapon of choice in the South Bronx because once a n*gga headbutted you, you really had few actionable comeback options.

I’m joking of course. Kinda.

My father had a tight grip on the bottle and loose hands when it came to my mom, so she left him for good when I was seven. I never saw him after that. I am in my forties. Never really missed him. It is a loss that had a tumultuous and giving beauty. He gave a five-speed Schwinn, and I am told his dimples and charisma, so there is that. Like most hoods, mine had categories of poverty, there was poor, there was po’ and then there was P (pronounced Puh) for all those folks like my family who were so poor they couldn’t even afford the two “o’s” and the “R.” I have lived on both coasts. My mom heard Gladys Knight and when she said L.A. proved too much for the man, she figured she was a woman and what was too much for the man, would be just enough for a strong woman.

So we moved to Los Angeles—South Central, Los Angeles, to be precise. When you are from the bottom and you change cities or states most often you don’t really change your dire circumstances, you simply rearrange them into different categories of despair, which you hope will be more manageable. It was also a dangerously magical place but that experience was given motive force. Literally. The automobile introduced a new concept into my ghetto lexicon: Drive Bys. I survived the killing fields. Many of my friends did not—including some who are still on top of the ground. The Walking Dead was reality show in my hood long before AMC came up with a television show.

I wouldn’t say I am “thugged out” but you won’t find me sipping tea with my pinky poked out, either. I would say I am a combination of two types of educational systems — the ‘hood and the good. I believe that what defines a person is not what knocks them down, but what they get up from. There is nothing really all that exceptional or outstanding about me. I am not the kind of cat that is going to turn heads, but my being– the way I exist in the world, my sense of style, humor and personality have opened many doors over the years, and I have tried to hold the door open long enough for another sister or brother to get through. I try to live well, treat people well, and maybe, leave a footprint here, a fingerprint there that says I was here, and that maybe I touched someone, left an impression or a set of footprints for others to follow.

Now back to this tumultuous and giving beauty of loss thing. None of us escapes loss.  There are only those who fashion it into something giving and beautiful and those of us who allow it to metastasize into a kind of absent-presence in our lives.

There are only those who fashion it into something giving and beautiful and those of us who allow it to metastasize into a kind of absent-presence in our lives.

Absent-presence … another paradox, I know.

But often we spend so much time focusing on our losses that the absence actually becomes a huge presence in our lives, crowding out other fertile, life sustaining possibilities. In other words, we let the things we don’t have take up so much space that we can’t enjoy the blessings we do have.

Mychal: As I read you letter I smiled because I saw in you a wonderful example of the giving beauty of loss. You are twenty-six, the exact same age as Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X when they stepped onto the national stage. In your story were you saw kryptonite, I saw the making of Superman. The Martin’s and Malcolm’s of our world are forged out of the sinew of hurt, self-doubt, loss and self-discovery; they are not born. Every brother in our society has what I call a Walter Lee moment. As you recall, Walter Lee Young is the character played by Sidney Portier in the film adaptation of Lorraine Hansberry’s generous play A Raisin in the Sun. Wonderful film, I’m sure you agree. If not, keep that to yourself, as our friendship is still fragile.

I’m joking. Kinda.

If you recall there is a moment in which Walter Lee has lost the money they inherited from their fathers life insurance policy. The family is worried about being able to move into the all white Chicago suburb of Clybourne Park after the neighbor “welcoming committee” has offered to buy them out to prevent them from integrating the neighborhood. At first he agrees to sell out. He’d been broken (or so he thinks). He feels the weight of responsibility and it’s crushing him. And when the moment of truth arrives, he looks at his son, his wife, his sister and his mother and he finds the strength to stand up and shoulder the weight of manhood. He rejects the offer and tells Mister Charlie aka Mark Lindner that he and his family are moving in after all. That’s the Walter Lee moment. Each of us has a Walter Lee moment where we must decide to stand up, shoulder the weight or buckle under it. Manhood is a process that ends in products even though the process never ends. Try not to give too much energy to arriving at manhood on time; it is far better to be in time. As an elder told me once in my rush to arrive, “All time is real and understanding that is power.”

Darnell: I don’t know what its like to be a gay man—word on the street is that I was trying to holla at the honeys in the nursery on the day I arrived—but I do know what it’s like not be loved fully by those who purpose in in part to love you fully, and what its like to live in a world that vociferously tries to deny my humanity. When I was younger I was one of those dudes that thought that to be gay and a man were antonyms. I was certainly a part of that riptide that pulled a lot of brothers just trying to keep their heads above water.

I’m sorry. Truly.

As I got older saw more of the world and saw more of world in me, I came to understand that what I was pushing back on was the ways in which gay men’s assertion of manhood disturbed my own notions of manhood. Much in the same way that Black agency forces white folks to have to recalibrate their sense of identity, so too does gay men’s agency force us as “straight” Black men to rethink our notions of manhood and gender. I think the term you used to describe this was “heteronormativity.” My dexterity with complex concepts sometimes get the better of me, I hope I didn’t do violence to what you meant. This is a far more intricate conversation with more nuances than space here allows. The flashpoints and trajectories of love, sex, sexualization, gender, power, identity, trauma, family, oppression, repression, community and the sociology of selfhood require a much more involved conversation beyond this epistolary moment.

Let me just say, the loss of the acceptance of ones humanity can be powerfully disabling, if we allow it to be. As I continue to grow up, I have come to realize that a part of growing into adulthood is about finding the world that welcomes you, all of you—or if you cant find it, having the courage and vision to create it. That, to me, is revolution.

Kiese: My man, though we barely know one another. Please know that I’m down for you like four flat tires. When you are not serving in your role as LeBron James’ publicist, you’re one hell of a scribe. In reading your letter and reflecting on Darnell’s letter. It is amazing to me how often we overlook how much of what we consider manhood is really the result of an unconscious process of brothers in contact and conversation with African womanhood but imagining that it’s a brothers’ only conversation. Much of our bravado, swagger and virulent sexism that informs the unstable elements of manhood are as much the result of whom we imagine women to be as it is about whom men actually are.

In other words, the loss of a kind of fundamental personhood, that has gendered expressions, has created an absent-presence that evidences itself as a form of solidarity in patriarchy, whose very sustainability requires a slow destruction of our best selves. That manhood within the context of patriarchy is not really manhood but what’s leftover when you negate “feminine” force. It is the celebration of the reflection in the mirror while hating image that calls the reflection into being. Like white supremacy, it is an identity built upon a shared lie, in which we, and many of our sisters, are complicit. To “give up the game” is to tell on ourselves. We protect sexism, misogyny and patriarchy not just to protect other men, but to protect that part of this shared lie that our own identities rest so unsteadily upon. This palimpsest of manhood needs to be erased in order to rediscover a kind of manhood that is constructed from a sense of personhood rooted in women and men in contact and conversation about what values animate our best spiritual selves.

I am reaching, I know. But to dream is free; it is the failure to dream is exorbitantly expensive.

If I can return to a nod that gave to A Raisin in the Sun in my reply to Mychal, Walter Lee has his rites of passage, but in the truest African sense, it is the women of the village, the Younger women, who give him their stamp of approval, when the Mother says to Walter Lee’s wife, Ruth, “Walter Lee done come into his manhood right nice today” and she says “Yes, he did.”

It is the fool who imagines himself a writer with pen with no ink, and it is the fool who thinks that only men create and shape other men.

Kai: I so appreciate your willingness to share a part of your journey and your willingness to be honest enough to know enough about your struggle to say you are still uncovering you. When Kiese asked me to participate in the conversation and to reply to all the letters, I thought “I got this. How hard can it be to respond to brothers talking and thinking about a spectrum of manhood?”—and then I read your letter. A woman who becomes a “transman” and who loves women and men is a book, not a letter. I wanted to know more about what unique insights you might have about men, about women, about life as a transgender person, as a person of African ancestry (or what some is metaphorically known as Black) and how these multivalent perspectives informed your thinking, being, and doing as a transman. Reading your letter put me in mind of the work by Lorand Matory’s Sex and the Empire That Is No More: Gender and the Politics of Metaphor in Oyo Yoruba Religion and Ifi Amadiume’s Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society. Both examine the intricate ways in which Africans have thought of, conceptualized, understood and inhabited gender and identity within specific cultural context. Stay with me: I also wonder to what extent our investment in western worldview delimits our ability to understand gender and identity as spiritual realities that have material manifestations.

Is it possible that one could be born with a woman spirit in a man’s form and vice versa? I don’t know. What I do know is that African societies have wrestled with these questions in the past relying on worldviews that accommodate much more expansive operational notions of gender and identity. Of course, by now you must also be thinking but what about the LGBT sentiments on the continent? I would note the impact of colonialism but also that all societies have their range of complexities and contradictions and that we must examine all of it in the hopes of constructing a more harmonious world, a world that welcomes all of us, or as I said before, the courage to create a new one.

I was educated within a tradition that taught me that the goal of thinkers and scholars is not to produce answers but to ask better and better questions. Perhaps in some ways your courage will yield better and better questions. I hope you maintain the courage to pursue them openly.

Marlon: Kierkegaard wrote that we live life forward and understand it backwards. I suppose there is a quality of truth in that statement; that looking back offers us the opportunity for reflection that helps us understand our current location. But what if you’re in an unlit tunnel and all you see is darkness whichever direction you look? In the midst of the darkness, your sensory perception begins to slowly erode and as we find ourselves in a kind of suspended animation, stumbling blindly through the forest of patriarchy in search of a emancipatory manhood. I don’t know, but I think a lot of brothers feel that way. I know I did once upon a time until some good men turned on the light in my life. In that space, prison seems like an improvement for some of us.

The walls can sadly orient us.

The walls can sadly orient us.

It’s horrible situation to feel like one is in prison whether incarcerated or not. I’ve been incarcerated before—twice— but never in “Mister Gilmore’s house.”

I have always been blessed with good women in my life, but I wasn’t always good to them when I was younger. In fact, I was quite mean at times. I have never raised my hands to a woman, but I wont front and say that its something I never considered. And while I am proud of that, I know that I have been emotionally abusive. I see infidelity as a form of emotional abuse too.

It wasn’t until I decided to confront my own hurt that I began to change and move closer to the man I wanted to be. And bruh, confronting that kind of hurt is like ripping duct tape off of a gaping wound and pouring rubbing alcohol on it.

That shit hurt! A lot.

I suspect that’s why so many of us seem unwilling to do it. So we simply expressed that deep hurt in other ways. Some of it is constructive but most of it destructively. I don’t have to tell you how repressed anger and hurt eat away at the body and soul. I think there is giving wisdom in your father suggestion that we not suffocate our spirits by holding in love. But loving is a circle and once we give it, we also open ourselves to receive it and that love at times can remind us of loss and hurt. To avoid that that loss, we simply break the circle. My hope for you is the same as my hope for myself that: that we find a good partner and love that partner like s/he is as essential to your life as oxygen. No matter the question, Black Love is always the answer.

Always.

Brothers, in looking over my letter I realize that I have violate the most basic rule of an epistolary relationship: brevity.

I apologize.

Among the Dogon of Mali, they have a system of knowledge that they divide into four degrees: 1) Giri So (Knowledge at face value) —understanding things at a surface level; (2) Benne So (Knowledge on the side)—knowledge based on other perspectives; (3) Bolo so (Knowledge from behind)—knowledge based on reflection, sankofa; and (4) So Dayi (Clarity)—to see things in all their “ordered complexity.”

In other words, deep knowledge involves understanding life forward, sideways, backwards and panoramically. Live life forward. My hope is that as we build, share, think and become better men that we do so with the kind of humility that acknowledges we not only have a lot of questions, but that we are also willing to live our way openly and courageously to the answers.

In life, love and liberation,

Ádìsá

Àdisà Àjàmú is the Executive Director of the Atunwa Collective, a Community Development Think Tank in Los Angeles, California. He is the co-author, along with Thomas Parham and Joseph White, of the fourth edition of The Psychology of Blacks: Centering our perspectives in the African consciousness (2010). Currently, he is completing two books, a collection of short stories and a collection of essays on African (American) life and culture.

Ádìsá Àjàmú

May 20, 2013

Dear First Lady and President,

I respect you. I wanted to be a rapper. I wanted to be a ball-player. Today, like most black men under 40, I am neither. Please complicate your analysis. You do the Dougie when convenient. You brush your shoulder off when convenient. You admonish black folks for not being you when convenient. You often talk to us like they’re watching. Because they are. In addition to all that “real talk” tough love stuff, black folks talk to black folks about white supremacy. Both of you y’all know this is true. We worry about your safety in spite of twisted real talk. We wish you would “real talk” to them about race and responsibility like we’re watching sometimes. Please complicate your analysis.

Today, I teach, write, and rap to myself. I am an above average writer and teacher. But when I’m on, I’m a problem, chile! I am working on being better at being human. I am not a father. Nor am I a husband. I am an American witness, an American writer. The most mediocre white man at my bougie job has 16x the wealth I have. You already know this. Please complicate your analysis. My grandmother has the beginnings of dementia, and she is still way smarter than me or you. She was only allowed to work the line at a chicken plant, work as a domestic and sell pound cake on the weekend. She has no wealth, but lots of love for both of you. She prays for your safety. She says that white folks have both of you niggas scared to tell the truth. She has witnessed a lot. She is not a liar. Please complicate your analysis.

Working class white security guards have entered my office 3x times asking to see my ID. Every time, I robotically tell them, “Fuck you. Show me yours.” I desperately cling to intellectual superiority over them; they desperately claim whiteness and relative wealth over me. This has nothing, and everything, to do with my wanting to be a rapper and baller. For better and worse, most rappers rhyme to us. Most ballers perform for us. You already know this. Why would you ever tell a throng of black men and black women to work twice as hard as white folks when there are so many examples of black brilliance and genius? Centering white mediocrity leads to black folks being just a little bit better than mediocre. I want to be better than my grandmother, the greatest American I know. She wants you to tell the truth. I respect you. We respect you. Please complicate your analysis.

Imani Perry writes books you should read. Please tell the truth.

Kiese Laymon is the author of Long Division and How To Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America.

May 16, 2013

Impact: A Meditation on Shame and Honesty — by Niama Sandy

Years after the last time we set eyes on each other and just months away from his wedding to someone else, he said to me “I will never be able to purge my feelings for you.” I felt like a hypocrite, suffocated by layers and layers of shame.

Years after the last time we set eyes on each other and just months away from his wedding to someone else, he said to me “I will never be able to purge my feelings for you.” I felt like a hypocrite, suffocated by layers and layers of shame.

Four years ago, I started regularly bumping into a guy we’ll call Jackson – by the way, that wasn’t a euphemism, at least not at this point of the story. I’d known Jackson for several years. If I had to estimate I would put the number at somewhere between 17 and 15 years; only the last five of which have been more than a cursory acquaintance. But as anyone might guess, that much time spent with someone on the periphery can lead to all manner of musings…

Tonight, I found a conversation from the summer of 2008, where Jackson very explicitly let me know he wanted to spend time with me. I was mildly intrigued, but rebuffed the advance because I had it on good authority that he had a girlfriend with whom he lived. And by good authority, I mean that I remember being introduced to her once several years before.

Me: “I doh really deal up in dem kinna ting.”

Him: “Most no nonsense females don’t”

Me: “So what? You figured you’d try anyway?”

Him: “That wasn’t a try.”

We barely spoke in the months after that conversation. Fast forward one year later and he wouldn’t necessarily have to try. In June of 2009, I saw him at a party. We hadn’t laid eyes on each other in years. We danced. There was something that passed between us. It is hard to put into any words but in short – weapons systems were locked. And so began my dance with death.

After that day, we started exchanging messages more often. Messages filled with plenty of profligate phrasings that would undoubtedly pose problems if his girlfriend ever knew about them. I thought I had all of these ideas about cheating and karma and so on, but onward I went.

One day in August of that year, I visited him. He was preparing to go somewhere and I had some folks to meet up with a few hours later. It was the first time we were ever alone. He was visibly blushing, and I very likely was too. There were some very charged moments but I managed to come away without having completely succumbed to temptation. I realized that I put my resolve in flux by even being there. At one point, Jackson brought his hands up to either side of my face, gently cupped it and kissed me. If Star Trek technology were real, I imagine that kiss was like what getting hit by a particle blast set to “stun.” My knees buckled, and to this day I have never again experienced anything like it. I knew immediately that it was going to be that much more difficult to stop.

Our communication ebbed a bit as a result of my last-ditch effort at self-preservation. I don’t know if it was sexual curiosity, budding feelings, a deep-seated sadomasochistic desire to upend my life but I couldn’t completely stop.

In November, there was more. It involved a couch, me standing over him on it, and more buckling knees.

One snowy December night, we met up for drinks. Interestingly, it took the entire night for things to escalate. I was on my way home and I realized that the five or six purple motherfuckers I had were about to cause my bladder to burst into smithereens. His house was closer to where we were on the train than mine was, so we got off. I went to the bathroom, but then things spiraled and the next thing I knew I was standing with my back pressed against a wall and one leg on his shoulder.

The following month, we spent a night together moving around New York from place to place. We danced, laughed and talked. The only time we touched each other that night was when he kissed me good bye before I left him to foolishly visit my ex. In hindsight, I may have been trying to pull myself out from his undertow. I was considerably less self-aware than I am now, so of course, that move backfired terribly.

Months later, he claimed my leaving that night “crushed” him. In some ways, my silly subconscious ploy created a new healthier distance between us since he was in a relationship with someone else. I’ve never considered that before those words made it to this page. I apologized but I’m not sure that I ever totally bridged that gap again.

Even despite that, we became great friends. He was the first person with whom I wanted to share all my news. We would spend the occasional night together in DC, usually after whatever party I hosted. I stopped thinking about his girlfriend. I generally stopped seeing other people. Oddly, I didn’t think about him on the few occasions when I did – all of which crashed and burned relatively quickly for one reason or another. As I write this, I realize there was so much fragmentation and disunity to my thoughts and feelings at that time. I was compartmentalizing at a level I never even knew was possible. I’m still struggling to even understand how I rationalized it all then. Impact.

In June of that year, I found out that my father was very ill. Seven months earlier, my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. By the time I found out about my father, my mother was in recovery and rehabilitation. Within a few weeks my father’s mysterious illness, he was diagnosed with stage-four lung cancer. The doctors thought he would have until the end of the year with palliative care measures in place.

I kept working 12-hour shifts, traveling for a contractor position I had on the weekends and doing it all over again the next week. Jackson knew about all of it, and supported me from afar. Unfortunately, the doctors’ estimation of how much time my father had left was wrong. There were masses everywhere in his body, many of which were visible to the naked eye as he became increasingly emaciated.

In early August, my father and I sat in a room at New York Methodist Hospital with our fingers interlinked. I felt my father’s his spirit leave his body.

Moments like those put your life in perspective. At that time, everything grinded to a halt in my mind; it became crystal clear that life was entirely too short to, firstly, not be satisfied with as much of life as possible and, secondly, to do so with as little stress as possible. My father’s death and the events that took place immediately afterward put my understanding of things on another level. Within a two-week span, so many of the other relationships in my life were irrevocably changed. Jackson was nowhere near me, physically or spiritually. In fact, he was away with his girlfriend.

I didn’t see him until September a full month later. There were so many things that I needed to say while we never had the time or space to say them. I saw him again a few weeks later in DC. I still didn’t speak on the thoughts and feelings. I knew I didn’t have him but somehow not having him at the moment, when it felt like parts of my life were coming apart at the seams, made the conditions seem a whole lot less livable. For months I had been keeping the situation from friends. There was so much shame. I knew I couldn’t carry that weight around.

I kept asking for time to be made have a conversation. He kept saying that I had to wait. Eventually, I got tired of waiting. I didn’t think about how much weight this peculiar situation may have put on him and how it may or may not have been affecting him. I was mostly concerned that the pseudo-relationship no longer seemed to be fulfilling any purpose in my life. One day in November 2010 I walked away.

Or so I thought.

I never wanted to ask him to leave – I wanted him to do it on his own. In either scenario, in our popular understanding and constructions of the dynamics of relationships, the logic is “he did it with you, so he will do it to you” – even if there were all these feelings that mitigated that supposed truth.

I have hundreds of messages from the following two years where issues were talked around but never resolved. He made mention of seriously considering moving to DC (where I lived at that time). I made mention of the fact that I had no knowledge of any of that because he never speaks in plain English. He said there was bad timing. I said we are responsible for making good use of time. He said he felt like I had given up on him.

I had.

There were deflections upon deflections, declarations of feelings but nothing about the mechanics of the situation changed thus making all of what was said phantasmic. Some time last year, Jackson asked his girlfriend of many years to marry him.

She said yes.

For a split second, the ghost howled its way back into my heart but I banished it and I congratulated him.

A few months later, in our first time speaking to each other in more than a year, Jackson said “I loved you and I still do. I don’t know how this is going to play out.” When he said it, something in the pit of my stomach tightened. I told him how unfair all of it is to his now-fiancé (who I suspect can’t possibly be totally oblivious to all this but it seems she has chosen to pretend she is). In all of this, I have learned that honesty, the whole truth, is the single most important aspect of a strong partnership. It is the only antidote I know of to distrust, dysfunction and shame. I hope that one day he will trust himself and her enough to be that honest, but right now, I really have to worry about myself.

I am no longer ashamed of my complicated relationship with him. The relationship was/is, and I’m not sure there is anything I can do to change that. Today, I am still struck by the level of selfishness and convenient ignorance that both of us displayed for such a long period of time. But still, I learned.

I learned to express love – whether for yourself or another – means sometimes, letting go. I understand that my loving Jackson isn’t contingent on being with him or feeling like I have to stake a claim on him. I understand that he, and our relationship, are not property.

I know that so many people have a very dichotomous view of most things in this world – things are constructed in our minds as either “it is” or “it isn’t” – regardless of what “it” is – love, sex, wealth and so many other supposedly objective concepts are included in that. The older I get, the more I realize there are so many grey areas in places where we insist they should be black and/or white. There is no space for plurality, for acceptance of both shame and honesty. We see there mingling as impractical, requiring a little more stretching of the mind and heart than most of us are willing to do. But I finally know that an acceptance of our plurality is really our only chance at health. Without it, there can really be no healthy love of ourselves or anyone else. Without it, there can be no meaningful impact. I learned this late, but I’m thankful I learned it all.

Niama Sandy is a London-based Brooklyn-transplant of Caribbean heritage. She is a force to be reckoned with in any creative arena she sets foot – whether writing, music, fashion or photography. A graduate of Howard University’s illustrious School of Communications and current Masters student at the School of Oriental & African Studies, Niama is lifelong creator, lover, patron of the art of life.

April 22, 2013

To The Bravest Man I Never Met

To the Bravest Man I Never Met:

I know that you’re out there, tortured and silent on a field or court, in a weight room, or addressing the media in front of a locker. It must be painful in ways I can barely begin to imagine. Living as a shell amongst men you consider your rivals, your colleagues, and your brothers. Many of them share a dream with you, sacrifice and toil with you, celebrate and revel with you, yet openly shun and curse you without even knowing what they’re doing. You’ve found the will to accomplish all that they have, while carrying a terrible burden. You are strong and brave beyond words for achieving and maintaining your place in your league. You deserve the pay, the fame, and the opportunity to live your childhood fantasies. You deserve everything that you have, and we deserve to know you, all of you.

You’ve undoubtedly spent a large portion your life creating or perpetuating a lie to shroud your natural elegant truth. You’ve hidden both your lust and your love from the world. You’ve abandoned, stifled, or at the very least concealed your deepest connections to other human beings. You’ve been forced to question a huge portion of your identity, to be treated as an abomination, and for what? For the sake of crude locker-room humor? So the most masculine men on the planet can parade their sexuality? For road trip runs to strip clubs in a lonely effort to cast aside all doubt? So your willfully ignorant bigoted peers can spew hateful bile in the media, and face nothing more than a public scolding?

You’ve undoubtedly spent a large portion your life creating or perpetuating a lie to shroud your natural elegant truth. You’ve hidden both your lust and your love from the world. You’ve abandoned, stifled, or at the very least concealed your deepest connections to other human beings. You’ve been forced to question a huge portion of your identity, to be treated as an abomination, and for what? For the sake of crude locker-room humor? So the most masculine men on the planet can parade their sexuality? For road trip runs to strip clubs in a lonely effort to cast aside all doubt? So your willfully ignorant bigoted peers can spew hateful bile in the media, and face nothing more than a public scolding?

I know a part of you wants to show us that you’re not ashamed, that you aren’t weak. I know that deep down you want to expose us all to the beautiful complexity you present. I wonder what you tell yourself. That it wouldn’t be worth it? That you’d put yourself and your loved ones at risk? That your unaware friends, family, teammates and coaches would feel betrayed and never trust you again? That your congregation will turn its back on you? That you’d be throwing your career away? That you’d be defined by your decision to speak out? I don’t doubt for a second that any or all of these fears could easily manifest. Still, I know you’re out there, terrified of the enormity of your potential.

We need you.

As a nation, as a culture, as a species we need you. Our collective consciousness rests at the precipice between collectively embracing the full spectrum of our humanity, or retreating back to a polarized world of purity and sin. We need you to push us, drag us if you must. We need you to begin to reopen the wound so we can drain out the poison we’ve been ingesting for generations. We need to stop losing brother, sisters, cousins, sons, daughters, uncles, aunts, friends, classmates, teammates, and lovers to suicide, depression, and self-destruction. We need to stop accepting religion and pseudo-science as excuses for destructive hatred. We need you to do what Tiger and Michael wouldn’t. We need to stop trying to fix you. We need your truth. We need your voice. We need your image.

We need you out.

How can I ask you to risk so much? Who am I to demand that you give up your anonymity, risk your career, and face the collective hatred of every homophobic piece of shit in America? How can I possess the audacity to demand that you place yourself and all that you love in harm’s way? On what righteous ground do I stand? The truth is that I have no right to murmur these thoughts, let alone publish them in the public domain. Please know that if these words ever reach your eye or ears that like almost all acts of love, my request is as selfish as it is selfless, and for that and nothing else I am sorry.

Ultimately I am just a stranger, one of millions waiting to embrace you, and all that you could represent. I’m waiting to listen to your interviews, read your memoir, rock your bracelet, and chant your name. Waiting to tell our children about where we were when you came out to the world. Waiting to watch you run, jump, swing, throw, tackle, or shoot. Waiting to forget why we even needed you in the first place.

Whenever you’re ready, we’ll be waiting.

Humbly yours,

- Parker

Matt Parker was born and raised in the Hudson Valley in NY where he attended Vassar and Bard in preparation for a life in the classroom. Matt has taught in Japan, the South Bronx, and Washington DC. He currently teaches biology to ELL students at TC Williams High School in Virginia.

March 16, 2013

Fossilized — by Daren Jackson

I stood behind the one-way mirror and watched Shannon sitting on the couch. With the dull hum of rain hitting the window behind her, she absentmindedly flipped through an issue of Business Week, no doubt making mental notes. It was 8:57 A.M., and she was scheduled for a 9 o’clock appointment. I’d invite her in at 9, and we’d end at 9:50, promptly.

I stood behind the one-way mirror and watched Shannon sitting on the couch. With the dull hum of rain hitting the window behind her, she absentmindedly flipped through an issue of Business Week, no doubt making mental notes. It was 8:57 A.M., and she was scheduled for a 9 o’clock appointment. I’d invite her in at 9, and we’d end at 9:50, promptly.

After thirty minutes of her catching me up on her previous week, she dropped this gem on me. “I hate the Starbucks culture.” She picked up her coffee cup from the end table. “Look at me. I’m sitting here drinking a Starbucks coffee because it is popular and convenient. Sure, it tastes great, but it was overpriced. And that’s annoying.” She sat tall in the chair. “It almost makes me purchase a more inconvenient, poorer quality coffee just to avoid it. But what really gets me, you know, what really gets under my skin? It’s the casualness of everyone there. The lattes, the laptops, the flip-flops … I can’t stand it. Especially how everyone looks ‘too cool for school’, like ‘I know I could be using my time more productively, but I choose to sit here wallowing in the aroma of roasted beans just because I can.’” It took her a moment to catch her breath. “Mostly though, I’m jealous of their ignorance. It really is bliss, you know? Some people just live life on such a superficial level,” she said shaking her head with squinted eyes. “That luxury has not been afforded to me.”

She had a way of going on about nothing sometimes, but it was her dime. “Is that what you want to discuss today? What you have missed out on in life?”

She looked up and to the right to find her answer. “Here is my real issue. I’ve always been a person full of drive. I’ve accomplished everything I’ve set out to do. But I’m turning 25 next month, and I’m stuck. Frozen.”

“Okay, let’s explore that. What does being ‘frozen’ mean to you?”

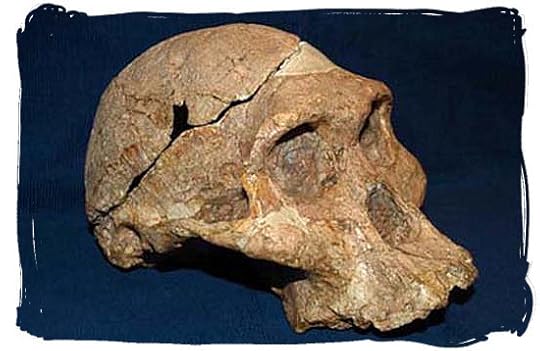

“I’m not sure how to explain this … well, have you ever seen that movie Jurassic Park?” I looked up from my notepad and peered at her over my frameless glasses. I didn’t make any audible reply; I just sat, legs crossed, trying to suppress that quizzical look I make sometimes. “Well, that’s kinda what my life has been like. I mean, not the dinosaur amusement park thing, but how they made the dinosaurs in the first place.”

“Mmm hmm,” I hummed.

“Remember? It was all possible because of fossils. They found mosquitoes fossilized in amber and used the DNA they had in them, plus extraneous reptile DNA, to recreate dinosaurs.” Shannon always spoke as if she was 100% confident in what she had to say, even if she wasn’t. Most people probably couldn’t pick up on this, but then again, I am a professional.

“Yes, but how does this relate to your feelings about your life?”

She huffed as if I had interrupted her in the middle of a rehearsed speech. “I’m getting there,” she said. “I grew up in L.A. I loved life and I loved my family and friends. My mom and I were really close. I still remember how she would sometimes sit me down to cornrow my hair on weekends. I’d fidget while strategically positioned on a pillow between her legs, and we’d talk about a million different things.” As she reminisced, she slightly cocked her head to the left and leaned forward off of the hulking leather chair. There was a vulnerability that I hadn’t seen from her before.

Progress, I wrote.

“She never missed any of my basketball games and she’d let me help her make dinner as long as my homework was done. That kitchen was so small that our butts would rub up against each other if either of us moved.”

“Okay,” I said. It could get painful listening to her diatribes and waiting for the point.

“Anyways, everything changed my junior year of high school. She thought she had finally found love.” Shannon paused, waiting for a response that I didn’t have. “She thought she found love, and he didn’t want me.” Her voice trailed to a whisper. The warmth drained from her face. “She had what she wanted, and it was like I had just become an obstacle to that.”

“How did that make you feel?” I said, leaning forward a bit in my chair.

“I was just lost for awhile. The pain was just too much and I didn’t know how to manage it. Then I went numb.” The braids on the top of her head started to fall over her face and she quickly pulled them back. She wrestled them into a ponytail as she continued. “I mean, she told me that I had to go. That I could take care of myself now. That I was grown. But, I didn’t have anywhere to go. And you can’t really support yourself on wages from an after-school job.”

“So what did you do?” I asked, a little bit more excitedly than I liked.

“I left California. Bought a bus ticket and headed to my aunt’s house here in Seattle. I still had goals that I wanted to accomplish and they had to take precedence over everything else. So, I turned myself off, set my sights on college, and threw everything else out the window.”

“That’s an amazing testament to your strength. Not to mention maturity.”

“I affectionately refer to that time as my ‘wilderness years’. My aunt wasn’t ready or even in the position to raise a child. She was rarely there. But she did keep a roof over my head. And at the time, that was the only thing I couldn’t do for myself.”

“Fascinating. How do you cope carrying that around with you? I’d imagine you’re not over it yet. It’s still so fresh.”

“I’m a new person now though,” she said straightening her shirt. “None of that means anything to me anymore. And to tell you the truth, I don’t even remember most of it.”

“I might do the same if I were in your position, but what about the life that you had built and had to leave behind? Seems there was a lot there that you cared about.”

“I basically had to let that life go. It wasn’t mine to have anymore. And that’s where Jurassic Park comes in. I’m a recreated version of me, with a few improvements. As far as I’m concerned, I was born at age 18.”

Peering over her head, I noticed that the clock read 9:54. “I’m glad you brought that full circle. We’re out of time right now, but I want you to think about this for next week. Does what happened to you affect you at all anymore? As people, we can suppress or hide a lot of things from ourselves and not even know how much it still affects us. Spend at least an hour this week just thinking and writing about how you feel and why. I’d really like you to fully come to terms with what you have experienced.”

She stood from her seat and extended her right hand. “Thank you Doctor Simms. I think this was a productive session. I always feel a little bit better after we talk.”

As I drove home through the Seattle rain that evening, I replayed the clients I had in my office that day. Kenny was having a hard time socializing and being honest with his co-workers. Sheila was having some struggles within her marriage and was contemplating divorce. Jonathon was just scared of life as a retiree. All of these cases were the usual. I’d seen people just like them before. All they really needed was an impartial party to help them get to the root of their feelings. Deep down, they already had the answers they were seeking.

Once I thought about Shannon though, I felt a little bit of a rush. She was a challenge. She was the test that I had been craving over the past few years since my practice had fallen into monotony. To anyone that might interact with her on a daily basis, she would seem perfectly exceptional. A faultless high-powered business woman in the tech industry. But underneath it all, there was so much unresolved and uncharted. Even with her success, she still felt that she hadn’t done enough. She still felt stagnant and bored with life. She needed a challenge as badly as I did and I was determined to crack her façade.

I stewed in silence for most of dinner. “Do you like the stroganoff, honey?” my wife Alicia asked.

“Yes. It’s lovely.” Half of the meal was still on my plate, but I hadn’t raised my head to look at my wife since I sat down. And she didn’t question me on it. She was nurturing in that way.

Even after dinner, once I moved to my office, she made sure to keep our 3 year old Maurice on the other side of the house. I appreciated the calm. I turned on some Mozart to help sort out my thoughts. And the nagging thoughts that I kept going back to were of my own childhood in rural Virginia.

Where I grew up, all of the homes had large plots, and my family had its own little farm with rows and rows of cornstalks and an assortment of fruits and vegetables. I have the most vivid memories of sitting on our front porch and inhaling the sweet aroma of our blueberry and raspberry bushes. And at the back corner of our house there was a peach tree that hung in a fashion that formed the perfect enclave.

I spent a lot of lonely humid afternoons under those branches, reading books, eating freshly picked peaches, and wiping the corners of my mouth with the back of my hand after each bite. There, I could retreat from a world that had not accepted me.

I always wanted to stick my nose in a book and my classmates wanted to rip and roar down the dusty dirt roads. I missed the boat on Motown and funk music. I wasn’t into sports, and I would have shook my head at talk of sneaking into the city to see a Blaxploitation film. On top of all of that, my mother insisted that I wear my brother’s hand-me-downs.

Even still, I wanted to belong. There was this whole culture and set of customs that I didn’t feel a part of, yet there was a daily reminder in the mirror telling me that I was supposed to. I wanted to be black like everyone else.

But I wasn’t. I wasn’t accepted.

One evening my father came home late from work at the factory. I could smell the beer trail behind him as he walked by me. I continued washing dishes, careful not to look his way. He pulled a bottle of beer from the refrigerator and popped the cap off.

“Antoine, come with me out back,” he said walking through the screen door. My father wasn’t much of a drinker, and I knew that this would not end well.

He was leaning against a post on the back porch looking out into the distance.

“Do you know what people say about us?” he asked.

“What do you mean?”

“What people say. You know, the sounds that come out of people’s mouths. The talk around town.”

“I don’t really pay attention to what other people think.”

“Don’t lie to me boy. You know one thing I can’t stand is a liar. You know full well what everyone around here says. And I’m getting tired of hearing it.” I watched him speak into the evening air and kept my hands clasped behind my back. I wondered how many drinks he had before he came home. “I hear people laugh under their breath at work. I see the strange look in people’s eyes when I go to the store. You’re too damn smart to not notice those things too.”

“Yes, sir. I’ve noticed.”

“And you don’t do anything about it?” He turned and started pointing at me with the beer bottle. “You just march along like this is normal?”

“What should I do sir?”

“What should you do? The smartest kid in the county is asking me how to solve a problem?” I wanted to take pride in that statement, but all I could feel was disappointment. “I love you, son. But you don’t make no sense. I was the captain of the football team for God sakes. I don’t understand how something like you came out of me.”

“I could try to be different. Maybe I can try out for the track team next year. Or at least be an aide for the sports teams. Momma promised to take me clothes shopping this summer too.”

“Nevermind. It’s no use. You are what you are. No sense in making the situation worse by forcing it.” He walked back to his post. “Dear God! Why couldn’t we have a normal child? Out of all the men in the county, how in the world did I get the white kid?”

I swallowed his words down to my gut. “Sorry, Pop.”

That night, those words repeated over and over in my head while I tried to sleep. They hurt, but my father was right. No matter how badly I wanted to be like everyone else, I wasn’t. And I was stupid to think that anything else could ever be the case. There was nothing I could do that would change who I was.

So when I left for college, I shook my father’s hand firmly before I boarded the Greyhound bus. I looked him right in the eyes and studied his face so that I would always remember it in that moment. We both knew we would never see each other again.

I had decided to embrace my lot in life. I still didn’t know how “Blackness” figured into my framework, but if I couldn’t understand myself, I could at least try to understand everyone else. I turned to the study of the human brain and social behavior. I stopped trying to understand what it meant to be Black and accepted the fact that I might be something else. Just like Shannon, I let my old life go. Antoine became Tony, and I built a life and a name I could be proud of.

“What’s on your mind, honey?” Alicia asked. We sat in the bed together while the 11 o’clock news played. I had been reading a book while she was talking back to the screen. “I know something is rattling around in there.”

“I was just thinking about my childhood. I had a patient today that triggered some memories.”

“Is there anything that you can share with me?”

“You know the rules,” I scolded. “Confidentiality. I can’t discuss it. Let’s just go to bed. It’s really no big deal.” I turned off the TV and we settled under the sheets.

It was two weeks later when I saw Shannon again. For once, the perennial Seattle showers had dried up and made way for simple overcast. There I stood with my hands behind my back, staring through the one-way mirror. Shannon sat on the couch with her legs crossed, rocking her leg back and forth like a metronome.

In the two weeks since our last session, I had been wrestling with myself, trying to think of the correct manner for handling this session. I’d been completely preoccupied with Shannon’s story, to the point that I would call it an obsession. Frequent, compulsive, and unhealthy. I needed relief.

“Doc,” Shannon started, “we had a really good session last time, and I really listened to what you had to say.”

“Ok, so did you do the activities that I asked?”

“Yeah, you said that I should take an hour to think about things by myself and write about it. So I did.”

“And what came out of that?”