Dan Ariely's Blog, page 55

July 5, 2011

Upside of Irrationality: Chapter 3

Here I discuss Chapter 3 from Upside of Irrationality, The IKEA Effect: Why We Overvalue What We Make.

June 20, 2011

Upside of Irrationality: Chapter 2

Here I discuss Chapter 2 from Upside of Irrationality, The Meaning of Labor: What Legos Can Teach Us about the Joy of Work.

June 15, 2011

Lessons about evolution from bird watching

By Amit and Dan Ariely

For the past few weeks, my 8-year old son Amit and I have been observing birds, paying attention to their individual and particular behavior. We noticed that some of the birds we observed were different in their physical characteristics like color, shape and size, and that these traits varied with their behavior. This made us wonder about the possible evolutionary links between the appearance of the birds on one hand and their respective behavior on the other.

The first difference that stood out to us was between the small and large red birds. Although the larger ones were about twice as big, their ability to fly was about the same — but what was very different about the two kinds was that the larger red birds were much more aggressive and caused more damage when they attacked. Of course, the evolutionary reason for this difference in aggression seems straightforward; as the subtype of birds gets larger, they need more food, and with this increased requirement, aggression becomes an important survival skill.

The yellow subtype of birds were slightly more of a challenge to figure out. Other than being yellow, their general characteristics were similar to the red birds — but Amit and I couldn't help but notice their tendency to suddenly fly at much higher speeds relative to the red birds. We speculated that the evolutionary reason for this difference must be that the red birds, by virtue of their threatening color, are less appealing to predators, and as a consequence they never needed to develop enhanced speed to escape. In contrast, the yellow birds practically invite predators to dine with their appealing color. With this clear disadvantage the yellow birds are forced to rely on an alternative survival mechanism, in this case the valuable skill of speed.

Another interesting feature of the yellow bird is that it is sharper, perhaps because it is a species connected with the woodpecker family. The yellow birds' sharpness might also help it further when it needs to break down a structure or cut through wood – which again is most likely connected to their need to compensate for their color disadvantage.

The blue birds were fascinating in their ability to self-replicate, and in all of the cases we observed they produced exactly three offspring. We wondered why the blue birds evolved to produce offspring at such speed and timely consistency, and we determined that the evolutionary reason for this must be that because the blue birds are small and relatively slow, they had to develop a skill for efficient reproduction, thereby hedging their bets and increasing the potential to pass on their genes.

The white birds were even more puzzling. On multiple occasions, we watched them drop their eggs while still in flight, naturally crushing the egg. Initially this seemed to be a counter-evolutionary strategy, but once we inspected the discarded eggs we realized that these eggs were abnormal, and it was probably the white bird's strategy for dealing with eggs that have a low potential for survival. One additional observation in support of this hypothesis is that the white birds seemed to be much healthier, lighter and happier after the eggs were discarded.

Of course there were many other birds as well, including one particularly interesting black bird, and Amit and I are thinking of continuing to pursue this bird-project for a while. In fact, we are already getting somewhat addicted to it, and we just learned that there are plenty more birds to observe in Rio.

But what really baffles us is this: why are these birds SO angry?

Amit and Dan

June 10, 2011

Preferences leading to choices?

Quite a few years ago (when I was 30), I decided that I needed to trade in my motorcycle and get a car. There are of course many cars on the market and I was trying to figure out which one was the right one for me. The Internet was just starting to boom with decision aids and to my delight I found a website that was providing car purchasing advice. The website was based on an interview procedure that started by asking me a lot of questions that ranged from my preferences for everything from price to safety, lighting, braking distance, and so forth and so on.

I answered all the questions which took me about 20 minutes, and at the end of the process I was eager to see my personalized recommendation. After each page of answers I could see the progress bar indicating that I was inching closer and closer to my ideal car. The last screen of questions was filled with my answers and all I had to do was press the submit button. I pressed the button and in just a few seconds I got the answer – according to this smart and intensive website, the right car for me was ….. a Ford Taurus. Now, I may not know much about cars — in fact I know very little about cars — but I did know that I did not want a Ford Taurus (nothing against the Ford Taurus, which I am sure is just a fine car).

What would you do in such a situation? I did what every creative person would do and went back into the guts of the program, changing my answers to all kinds of questions ranging from my preference of price to the importance of safety, braking distance, and turning angle. Once in a while I would check how different answers translated into different car recommendations. I continued with this for a while until the program was kind enough to recommend that the right car for me was a Mazda Miata. The moment I saw that the software's recommendation was a small convertible, I realized this was a fantastic and wise program whose advice I should follow. And so I became the proud owner of a Mazda Miata, which served me loyally for many years.

What I learned from this experience is that sometimes (perhaps even very often) we don't make choices based on our internal preferences. Instead we have a gut feeling about what we want, and we go through a process of mental gymnastics and rationalization in order to manipulate our choices so that at the end we can get what we really want but at the same time keep the appearance (to ourselves and to others) that we are acting according to our preferences.

This process, where we make a guttural decision first and then recruit our cognitive skills to justify our desires, is not restricted to software — and it is something we do often and with both small and large decisions. If we accept that this is often how we make decisions, there is one way to make this process more efficient and less time consuming. Imagine you're considering two digital cameras: one superior in mechanics like zoom and battery, and the other with a snazzier shape. You're conflicted and not sure which one to get. If you realize that the source of your confusion comes from knowing that one camera is technically better but that the other will make you happier, you can try the "coin toss method". Here is how it works. You assign one camera to heads and one camera to tails and you go ahead and toss the coin in the air. When it lands, you see your decision. If you got the camera that you wanted, good for you — go and buy it. But if you're not happy with the outcome, continue tossing the coin again and again until you get the desired result. Now you not only get the camera that you really wanted but you also can justify your decision because you were simply following the advice of the coin.

Perhaps this was really the function of that software — not to get us to make better decisions, but to allow us to justify what we really wanted, and at the same time feel confident and good about it. If this is the case then I think the software was a great hit, and we should develop similar products for many areas of life.

June 5, 2011

Upside of Irrationality: Chapter 1

Here I discuss Chapter 1 from Upside of Irrationality, Paying More for Less: Why Big Bonuses Don't Always Work.

May 30, 2011

A Behavioral Economics Summit for Startups

Introducing Startup-Onomics

Startup-Onomics is about infusing behavioral economics into the core DNA of new companies.

Through interactive lectures in the morning and 1:1 working sessions with famous industry experts in the afternoon, you'll walk away with the scientific tools to better understand your customers and build products that meet their needs.

These techniques are proven to increase site conversion rates, create effective pricing strategy, improve customer and employee retention and overall help users change the 'hard-to-change' behavior.

What is behavioral economics?

As business owners, we want to design products that are useful, we want customers (lots of them), and we want to create a motivating work environment. But it's not that easy. In fact, most of the time that stuff takes a lot of hard work and a lot of trial and error.

Good news. There is a science called Behavioral Economics. This attempts to understand people's day to day decisions (where do I get my morning coffee?) and people's big decisions (How much should I save for retirement?).

Understanding HOW your users make decisions and WHY they make them is powerful. With this knowledge, companies can build more effective products, governments can create impactful policies and new ideas can gain faster traction.

For more details see:

May 25, 2011

Spider-man & Overcommitment

The Irrationality of Organizational Escalation: The Danger of Spider-man & Overcommitment

By Henry Han-yu Shen

Spider-man: Turn Off the Dark is an upcoming rock musical featuring music and lyrics from U2's Bono and The Edge and originally directed by Julie Taymor, best known for the hit musical The Lion King.

This musical is also the most expensive Broadway production in history, with a record-setting initial project budget of $52 million. The show's opening has been repeatedly delayed while the production cost continues to accrue, currently totaling a whopping 70 million dollars. The final estimated budget approaches 100 million dollars, with no guarantee of profit return and below-average reviews.

Spider-man's situation exemplifies a classic case of organizational failure. Marked by producers' continuously irrational contributions of monetary support to a seemingly hopeless project. In many ways this case is similar to the failed Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant program as analyzed by Ross and Staw (1993). The Shoreham project also experienced an escalation of project cost – from an initial $75 million to the final cost of $5 billion – and it a classical example of how organizations become increasingly committed to losing courses of action over time.

We can draw several parallels by comparing the Spider-man Broadway production to organizational escalation. We can see that economic data alone cannot easily deter organizational leaders from withdrawing from a full-scale course of action, especially in cases involving something that is highly subjective in its value (such as a Broadway production). When we consider that the cost of production for Spider-man continues to rise, the initial psychological over-commitment of the producers can become even stronger. Such forces appear to have come into play, trapping the producers into a losing situation while they continue to throw money into the project. It is important for future producers, or any organizational leaders, to keep in mind the existence and properties of these different types of escalating determinants in order to avoid clouded judgment and behavior when making decisions.

May 20, 2011

Depletion and parole

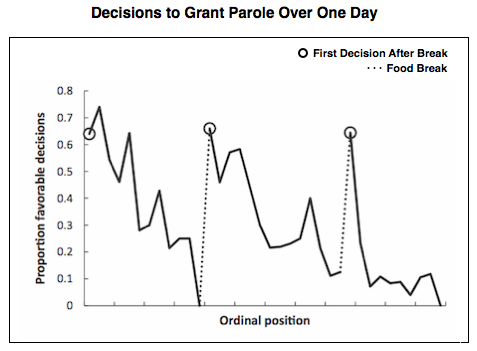

It turns out that being tired isn't just detrimental to exam performance. One theory in decision making that we are beginning to understand better, Depletion Theory, holds that our ability to make any type of difficult decisions are also adversely affected by fatigue. In most of our day to day lives, being tired at the end of a long work day doesn't lead to too many terrible decisions, maybe a candy bar here or there, or fast food when we should go for a healthy wrap. However, sometimes the effects are more significant.

Consider the dramatic results of a recent study by Shai Danziger, Jonathan Levav, and Liora Avnim-Pesso, investigating a large set of parole rulings of judges in Israeli courts. Their conclusion is striking. Judges systematically tend to grant parole when they are most refreshed: at the beginning of the day. After that their decisions change and the likelihood of granting parole drops as the number of decisions they make goes up. But the effect is not the same across the whole day — after their lunch break they get some extra energy that rejuvenates them and their decisions look much more like the ones they have made early in the day

It seems that the cognitive burden of making these difficult moral decisions builds such that over time it is easier and easier to simply accept the conservative, status quo decision not to grant parole.

May 18, 2011

Upside of Irrationality: Paperback!

The Upside of Irrationality has been released today in paperback! To celebrate this occasion, I will be releasing a few videos over the next few months — each discussing one of the chapters.

Here is a look into the the introduction:

p.s I just learned that the world is going to end on May 21, so if you want to get the book, do it quickly (and pay with a credit card).

irrationally yours

Dan

May 15, 2011

Wait For Another Cookie?

The scientific community is increasingly coming to realize how central self-control is to many important life outcomes. We have always known about the impact of socioeconomic status and IQ, but these are factors that are highly resistant to interventions. In contrast, self-control may be something that we can tap into to make sweeping improvements life outcomes.

If you think about the environment we live in, you will notice how it is essentially designed to challenge every grain of our self-control. Businesses have the means and motivation to get us to do things NOW, not later. Krispy Kreme wants us to buy a dozen doughnuts while they are hot; Best Buy wants us to buy a television before we leave the store today; even our physicians want us to hurry up and schedule our annual checkup.

There is not much place for waiting in today's marketplace. In fact you can think about the whole capitalist system as being designed to get us to take actions and spend money now – and those businesses that are more successful in that do better and prosper (at least in the short term). And this of course continuously tests our ability to resist temptation and for self-control.

It is in this very environment that it's particularly important to understand what's going on behind the mysterious force of self-control.

Several decades ago, Walter Mischel* started investigating the determinants of delayed gratification in children. He found that the degree of self-control independently exerted by preschoolers who were tempted with small rewards (but told they could receive larger rewards if they resisted) is predictive of grades and social competence in adolescence.

A recent study by colleagues of mine at Duke** demonstrates very convincingly the role that self control plays not only in better cognitive and social outcomes in adolescence, but also in many other factors and into adulthood. In this study, the researchers followed 1,000 children for 30 years, examining the effect of early self-control on health, wealth and public safety. Controlling for socioeconomic status and IQ, they show that individuals with lower self-control experienced negative outcomes in all three areas, with greater rates of health issues like sexually transmitted infections, substance dependence, financial problems including poor credit and lack of savings, single-parent child-rearing, and even crime. These results show that self-control can have a deep influence on a wide range of activities. And there is some good news: if we can find a way to improve self-control, maybe we could do better.

Where does self–control come from?

So when we consider these individual differences in the ability to exert self-control, the real question is where they originate – are they differences in pure, unadulterated ability (i.e., one is simply born with greater self-control) or are these differences a result of sophistication (a greater ability to learn and create strategies that help overcome temptation)?

In other words, are the kids who are better at self control able to control, and actively reduce, how tempted they are by the immediate rewards in their environment (see picture on left), or are they just better at coming up with ways to distract themselves and this way avoid acting on their temptation (see picture on right)?

It may very well be the latter. A hint is found in the videos of the children who participated in Mischel's experiments. It's clear that all of the children had a difficult time resisting one immediate marshmallow to get more later. However, we also see that the children most successful at delaying rewards spontaneously created strategies to help them resist temptations. Some children sat on their hands, physically restraining themselves, while others tried to redirect their attention by singing, talking or looking away. Moreover, Mischel found that all children were better at delaying rewards when distracting thoughts were suggested to them. Here is a modern recreation of the original Mischel experiment:

[image error]

A helpful metaphor is the tale of Ulysses and the sirens. Ulysses knew that the sirens' enchanting song could lead him to follow them, but he didn't want to do that. At the same time he also did not want to deprive himself from hearing their song – so he asked his sailors to tie him to the mast and fill their ears with wax to block out the sound – and so he could hear the song of the sirens but resist their lure. Was Ulysses able to resist temptation (the first path)? No, but he was able to come up with a very useful strategy that prevented him from acting on his impulses (the second path). Now, Ulysses solution was particularly clever because he got to hear the song of the sirens but he was unable to act on it. The kids in Mischel's experiments did not need this extra complexity, and their strategies were mostly directed at distracting themselves (more like the sailors who put wax in their ears).

It seems that Ulysses and kids ability to exert self-control is less connected to a natural ability to be more zen-like in the face of temptations, and more linked to the ability to reconfigure our environment (tying ourselves to the mast) and modulate the intensity by which it tempts us (filling our ears with wax).

If this is indeed the case, this is good news because it is probably much easier to teach people tricks to deal with self-control issues than to train them with a zen-like ability to avoid experiencing temptation when it is very close to our faces.

*********************************************************

* Mischel W, Shoda Y, Rodriguez MI (1989) Delay of gratification in children. Science. 244:933-938.

** Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Houts R, Poulton R, Roberts B, Ross S, Sears MR, Thomson WM & Caspi A (2011) A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth and public safety. PNAS. 108:2693-2698.

The original PNAS piece is here

Dan Ariely's Blog

- Dan Ariely's profile

- 3912 followers