Ada Palmer's Blog, page 3

December 3, 2021

Gender in Terra Ignota (Queership Repost)

18th century portrait of the Chevalier D’Eon, one of many prominent Enlightenment figures who help challenge ideas of gender, historically and today.

This is an essay I was invited to write in 2017 for the delightful spec fic blog Queersship, which has since ceased to exist, but many people have asked me to re-post the essay, especially now as the series finale is coming out. For a more recent (though less expansive) discussion of similar issues see my guest post on Nine Bookish Lives which asked me here in 2021 to discuss Terra Ignota and the question of “a future that doesn’t see gender.”

Going Deep into the Gender of Terra IgnotaFirst I want to thank Queersship for inviting me to write about gender in my Terra Ignota series, since gender stuff is probably the part of the book that took the most time and effort word-by-word. (Well, the Latin and J.E.D.D. Mason’s dialog were literally more effort per word, but there is a lot less Latin in the book than there are pronouns…)

I want to talk separately about two levels of what the book does with gender:

(A) the larger world building, and (B) the line-by-line pronoun use.

On the line-by-line level the series uses both gendered and gender neutral pronouns in unstable and disruptive ways, designed to push readers to learn more about their own attitudes toward gendered language as they grapple with seeing it used so strangely and uncomfortably. On the macro level, the series presents a future society which is neither a gender utopia where all our present issues have been solved, nor an overt gender dystopia like The Handmaid’s Tale, but something both more difficult to face and, in my view, more realistic: a future which has made some progress on gender, but also had some big failures, showing us how our present efforts could go wrong, or stagnate incomplete, if we don’t continue to work hard pushing for positive change.

At the beginning of Too Like the Lightning the main narrator, Mycroft Canner, addresses the reader directly, asking “forgive me my ‘thee’s and ‘thou’s and ‘he’s and ‘she’s, my lack of modern words and modern objectivity.” We soon learn what this means: in the 25th century world of Terra Ignota, people have no assigned sex, practically all clothing and names are gender neutral, English has stopped using gendered pronouns, and normal dialog always uses the singular ‘they.’ But in the narration Mycroft assigns gendered pronouns to people based on his own personal opinions of which gender suits their personalities. Mycroft insists that his history won’t make sense without the “archaic” tool of gender, a claim which invites the reader to judge Mycroft’s decision to do this, and to think about how this use of gender manipulates us and the narrative. So, Mycroft uses ‘he’ and ‘she’ in narration, while most characters use ‘they’ in their dialog. But this is more than Mycroft reviving the gender binary in a genderless world, since Mycroft applies gender in idiosyncratic ways no one would today—just as authors today who use ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ in literature practically never use them as they were actually used in pre-modern English. Mycroft’s understanding of ‘he’ and ‘she’ has nothing to do with biological sex, or anything we can recognize from how our society uses the words today, and learning about how Mycroft uses gender is our first window into the strange gender attitudes of the world he is trying to describe.

Illustration of unisex clothing used by “Drapers Magazine” for an article called “Unisex Clothing: Fad or Future?” a question I decided to zoom in on in Terra Ignota. The clothing is identical, but do our minds still assign gender to the wearers based on other cues? What cues? Can we change that about how we perceive gender?

World Building: An Age of (Gender) SilenceI want to talk about the larger world building before I go more deeply into Mycroft’s pronoun use. We learn early in Too Like the Lightning that the gender neutral language of this 25th century is not the result of society’s efforts toward inclusiveness finally succeeding, but the result of global trauma and severe censorship. In the twenty-second century a global conflict called the “Church War” devastated much of the Earth, and in the aftermath both religious discourse and gendered language were forbidden, by severe taboos and censorship laws. Using ‘he’ and ‘she’ is not just outdated in this world, it’s completely disallowed, and discussing religion without a state-licensed chaperone is a severe crime.

This element of the world is intentionally polarizing for my readers, creating a future that feels like utopia to some and dystopia to others. A world where family members are forbidden to discuss religion with each other may feel liberating to anyone who’s had nasty interactions with proselytizing parents, but oppressive to anyone who values religious community and heritage. Similarly a world where ‘they’ is the only permissible pronoun may feel liberating to some who see it as an escape from the current binary, but feels oppressive to anyone (whether cisgender, transgender, nonbinary, gender-nonconforming, or something else) who strongly desires to express gender, considering gender an important part of identity and wanting to be acknowledged with the pronoun of their/his/her/zir/its/etc. choice. But in the world of Terra Ignota, even Sniper—a character who actively prefers the ‘it’ pronoun because Sniper wants to dehumanize itself and be treated as a living doll—is denied the right to be ‘it’ if it wants, just as others are denied ‘he’ or ‘she.’ One of my big goals in creating this polarizing world was for readers to discuss their reactions with each other, exploring how one person’s utopia can be another’s dystopia, and exploring the tensions between our different ideals of religious freedom and of gender liberation—tensions we need to understand and address as we work together in the real world to create inclusivity which will work, not just for some people, but for everyone.

Our narrator claims in the text that this forced global silencing of gender and gendered discourse has resulted in a false gender neutrality, that under the surface people in his world still think in terms of binaries, and that inequality continues, just without anyone being willing to admit it. Real gender progress stopped short under the silence, so the society kept unconsciously passing on forms of gendered thought and inequality, not because they’re somehow ineradicable or biologically ingrained, but because the abrupt end of dialog meant no one was working to eradicate them, so they continued to be passed on. In a world that insists gender is gone, no one is doing studies on the pay gap, or discrimination, or gender ratios of politicians, or analyzing fiction for how it presents gender. Since the society declared that the big problems were solved, no one is watching for the effects of gender on the world anymore, so no one perceives those smaller problems which haven’t been solved, or tries to address them.

Dystopia’s like Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale are one way to look at ways the future could fail on gender – imperfect futures like Terra Ignota are another.

This is one of several threads in the series which press beyond the question “Does the end justify the means?” to another question: “Does a bad means poison the end?” Is gender equality achieved through censorship so problematic in itself that it might harm efforts toward true equality more than it helps? Is forced silence in the name of progress actually an enemy of deeper progress?

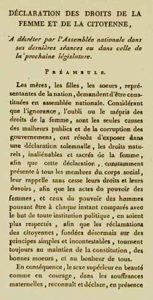

Put another way, in Terra Ignota I wanted to show a world that botched the endgame of feminism and gender liberation. Sometimes you hear people say things like, “Feminism is done, women have equal rights under the law, so we don’t need all this gender discussion anymore.” It’s a strategy people use to try to shut down discourse. But gender progress isn’t done. We’re only beginning, through psych studies and research, to understand how we unconsciously pass on gendered behavior patterns to children. We’ve only just realized how much we’ve been drowning our kids in stories where women have less narrative agency than men, and where ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ are harsh, unquestioned binaries. We’re only just beginning to produce new works that do better. Transgender and nonbinary gender rights and representation are in their infancy. And realistically in fifty years, with many legal battles won, these processes will still be in their infancy. Olympe de Gouge wrote her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in 1791, yet female suffrage didn’t gain momentum until the late 1800s, and we’re still struggling to make an equal space for women in politics even now. But imagine if feminist discourse had shut down in 1960 when the last Western nations adopted women’s suffrage. If we’d stopped the conversation then, declared that to be victory, then no one would now be doing things like watching the pay gap or writing feminist literature, and progress would slow to a crawl, or possibly stop entirely. And the same could happen to other forms of social progress (race, ableism) if their conversations are shut down. So, as a rebuttal to those who say feminism is finished and should stop, and who will in the future say that other movements like the transgender movement are finished and should stop, I wanted to depict a world where these conversations did stop, where silence fell in the 2100s, and we see the bad effects of that stagnation still affecting the 2400s.

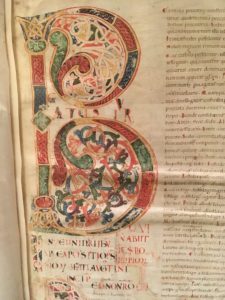

First page of Olympe de Gouges’s 1792 Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen

Pronouns: ‘Thee’s and ‘Thou’s and ‘He’s and ‘She’sAs for Mycroft’s line-by-line narration, one challenge I posed for myself in these books was writing from the point of view of a narrator so immersed in his world that he is inept and clumsy at critiquing it. I’m a historian, so, from reading historical documents all the time, I’m acutely aware that it’s incredibly difficult it is to start a conversation about an issue one’s society has silenced. When we read early feminist or socially progressive works, like Olympe de Gouge, or Mary Wollstonecraft, or Voltaire, or even Plato’s Republic (which argues that male and female souls are fundamentally the same; proto-feminism in 300+ BC!), we admire some of their ideas but often find their actual discussions of the subjects painful to read. Authors so early in the discourse tend to be so saturated with the outdated prejudices of their eras that a lot of those prejudices leak through, even as they seek to battle them. You see people fighting for women’s rights while voicing deeply sexist ideas about the attributes or role of women, or calling for the rights of people of color while using the condescending, infantilizing racist language that saturated the 1700s and 1800s. First generation members of a movement nearly always express themselves ineptly by the standards of their successors, because, when there has been no critical conversation about a topic, it is very hard for the first critics to get a good perspective on it.

So in framing my tale of the 25th century as a historical document, written by someone in the period, I decided to have that fictional author be limited by how plausibly difficult it would be for someone to start seriously discussing gender again when no one had done so in 350 years. And I chose to model the narration on 18th century narration partly because 18th century critiques of gender are brilliant-yet-inept in precisely the way I wanted to examine. Giving my narrator the sophisticated terminology of the 21st century would have made it too easy for his critique to become comfortable for us. Mycroft Canner, and also all the other characters we hear discuss gender in the books, all have deeply bizarre, twisted, and by our standards unhealthy ideas about gender. Because realistically that’s the best I think people could do as a first step in a world so wracked by silence, just as Plato and Mary Wollstonecraft’s works were the best they could do in their own eras. It’s disorienting reading Mycroft’s discussions of gender, and seeing his strange and uncomfortable attitudes, and the other characters who address gender are generally just as uncomfortable to us. And that discomfort pushes the reader to distrust all the pronouns and all the gendered language, to try to cut through Mycroft’s distorting perspective, much as we have to do when trying to get past the bias in real historical documents. It shows just how difficult it could be to restart these conversations after silence, which I hope will strengthen readers’ commitment to keep on pushing, writing, talking, and critiquing. To make sure silence doesn’t fall.

Thus, my narrator Mycroft, struggling to express himself, resorts to using ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ and also ‘he’ and ‘she’, assigning ‘he’ and ‘she’ based on which gendered archetype he associates with a character’s personality and actions, regardless of appearance. Mycroft’s gender categories are very idiosyncratic, and we learn about him by observing them, much as in Star Wars we learn a lot about Darth Vader observing how he uses ‘thee’ and ‘thou’. To start with, Mycroft’s own attempt to stick to a gender binary quickly breaks down. For some characters gendered pronouns fit easily, and do indeed help the reader make sense people’s actions, as when we deal with Heloïse, a nun whose religious vocation is deeply steeped in traditional ideas of gender, and who very consciously embraces an identity as ‘she’. For other characters, gendered pronouns are such a mismatch that even Mycroft resorts to ‘they,’ as with the human computer Eureka Weeksbooth. And for yet other characters Mycroft assigns gendered pronouns but they feel so irrelevant that there would be no change if one reversed them, as with the otherworldly Utopians Aldrin and Voltaire. (I’ve sometimes had readers forget what pronoun Mycroft gives each of them—I’m so proud when people forget!) As the series advances, Mycroft sometimes switches pronouns for a character, or apologizes to the reader for having trouble finding the right gender fit. For some characters, physical descriptions make it clear which sex the character’s body appears to be (Mycroft will mention a beard, or breasts, or genitalia) so the reader knows whether the sex matches the pronoun, while for other characters the reader is given no clue to the character’s appearance or biological sex other than the pronoun assigned by the narrator. All this strangeness aims to make the reader hyperconscious of the pronouns, and of the ways gendered pronouns mislead, clarify, distort, help, and harm.

In the new Graphic Audio cast recording audiobooks we get to make the gender complication even more acute by playing around with the perceived gender of the voice vs. the gender used by Mycroft

Some readers have told me that the book’s use of pronouns changed how they felt about the singular they, that they’d disliked it before, thinking of it as a distortion of grammar, but that Too Like the Lightning helped them see for the first time how manipulative binary gender pronouns can be, how ‘they’ can be a valuable and liberating alternative. (This was one of my big goals!) Other readers have told me they were surprised to find themselves obsessing over the ‘real’ genders of the characters whose genders aren’t clear, painstakingly tracking every hint in physical descriptions, and that discovering that they were doing this helped them realize for the first time how much they really do judge characters differently based on gender. (This was another big thing I hoped to help make readers conscious of.) Some readers have said they were particularly fascinated by their reactions to the characters whose physical descriptions clearly don’t match their pronouns, that for some characters they found themselves thinking of the pronoun as the ‘real’ gender while for other characters they thought of the physical description as the ‘real’ gender, and that this made them rethink how they understand the relationship between gender and bodies. (Brace yourselves for books 3 and 4, where things get even trickier!) I’ve been particularly touched when readers have told me that the books helped them gain more respect for the transgender movement and for transgender, nonbinary, and gender-noncompliant people, understanding at last why many people want so badly to be able to choose their pronouns and genders for themselves. (So proud when people have that reaction!)

In contrast, a couple of readers have told me they felt they didn’t get much out of the book’s strange use of pronouns, that it just replayed for them the familiar (and often painful) problems of assigned sex and the current gender binary. Writing intentionally uncomfortable fiction like Too Like the Lightning is high risk. For some people it hits too close to painful areas and just hurts instead of being productive. For others it’s too rudimentary, spending a lot of time demonstrating the manipulative effects of pronouns which many readers are already very conscious of. But other readers are not so conscious of them. Right now F&SF readers, and readers in general, vary enormously in how much we’ve thought about gender, about binary and non-binary gender, about transgender and cisgender, about intersex and agender—some readers live and breathe these issues every day, while others have just dipped a toe into the conversation. With readers in so many different places in that conversation, a book which one group of readers finds stimulating and productive may totally fail for another group. I know some readers have found the first book painful in a bad way, and whatever my intentions that pain is real and I’m sorry I caused it, that try as I might it was too difficult walking the line between the productively painful (1984 and A Handmaid’s Tale are very painful) and the unproductively painful. But I hope this essay will at least help those readers who found it too painful see that I was aiming for something constructive, even if, while I hit the mark for some readers, I missed it for others. And I agree 100% with my (amazing!) fellow Hugo finalist Yoon Ha Lee’s comment that it’s important that we accept works that try hard to address difficult topics, even if they don’t succeed as perfectly as we would like, because we don’t want to scare people off from trying. (And I can’t tell you how proud I am to be part of such an incredibly diverse group of fellow Hugo finalists!)

Portrait of Gustavus Hamilton Second Viscount Boyne (1730) in the Met. The combination of fashion and the way the lace hood normally worn under the Bauta mask looks like long hair challenge our 21st century expectations of how we are intended to parse gender.

Writing Mycroft’s inconsistent pronoun use was also a fascinating learning process for myself as an author. First, I worked out carefully what Mycroft’s own ideas about gender were, what characteristics would make him choose ‘he’ or ‘she’ for someone. Then, when I had mostly outlined the series, I went through and read over the outline in detail three times for each of the thirty-four most important characters (more than 100 rereads total), once imagining the character as “he” in the narration, another time as “she,” and a third time trying to think of the character without gender. For some characters I did more than three passes, when I decided to try something even more unusual with gender. My goal was to see how each character’s arc might feel different with a different pronoun. Some characters’ arcs felt much the same regardless of gender, while, for other characters, actions or outcomes felt very different when gendered differently, suddenly falling into a cliché, or defying one. I learned a lot about my own attitudes toward gender by seeing when the pronoun made a big difference for me, and when it didn’t. By making myself live through the four book arc of Terra Ignota 3+ times for every character, I made sure that I was 100% clear on how Mycroft’s choice of pronoun might change the reader’s feelings and expectations about each character, so I could be sensitive to that as I wrote the actual books, and make use of its potential to disrupt expectations. In a few cases where I felt Mycroft would waffle about which pronoun to use, I took the opportunity to have him use the one which would make the character’s arc more striking, or to have him minimize gendered language for that character to create a nearly-genderless arc, as with Eureka, Mushi, Aldrin, and Voltaire. In the end I found this gender-swapping reread process so productive that now I’m doing it with every story I outline, even if I’m not planning to do much with pronouns, since it’s such a great way to discover new narrative possibilities, and to notice when I’ve slipped into a gender cliché.

Once writing was underway, I also spent pass after pass through the manuscript hunting for inconsistencies in my own pronoun use, correcting ‘they’s to ‘she’s, ‘she’s to ‘he’s, ‘they’s to ‘it’s, and ‘he’s to ‘He’s (for the character who capitalizes His pronouns). Some chapters I wrote more than once with different pronouns to see how they would feel each way. Switching so constantly totally broke the pronoun habits in my own head, so that it leaked out into all my other work. While working on these books, I’ve constantly had the editors of my academic articles complaining about how I was switching between ‘they’ and ‘he’ and ‘she’, and once (my favorite) I got the baffled question, “Why are you using ‘she’ for Jean-Jacques Rousseau?” (In Terra Ignota Rousseau is ‘she’ by Mycroft’s rules of gender, but it wasn’t easy explaining that to an academic journal!) And some chapters are narrated by other characters who don’t use gendered pronouns at all, so switching from narrator to narrator also took great care (but gives the reader a much-needed break from the disruptive pronouns). In the end, even with the giant team effort of (I kid you not!) thirty-six beta readers, plus the editor, copy editor, and page proofer all hunting for (and finding!) inconsistent pronouns, a few still slipped through into the printed version, moments a ‘they’ that should be a ‘he,’ or vice versa. The process was exhausting, and imperfect, but more than worth-it—I feel that every time a reader tells me that it helped them discover new aspects of how pronouns affect our thought, our culture, and themselves. (Yes!)

Baroque 18th-century wigs recreated in paper by Russian artist Azya Kozina, a brilliant example of our contemporary fascination with how gender was performed in the 1700s, and how we redeploy those historical gender tools in our own era for our own ends.

Between Utopia and Dystopia:

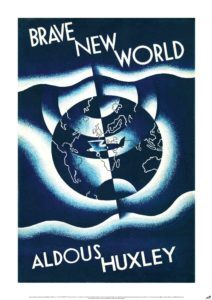

Between Utopia and Dystopia:Terra Ignota is neither a dystopia nor a utopia—it’s a future that has taken two steps forward but one step back. It has a lot of things that feel Utopian: flying cars, a 150+ year lifespan, a 20 hour workweek, a Moon Base, long-lasting world peace. Maybe 80% of the attributes of this world are the stuff of Utopia. But it has a lot of things that feel dystopian: censorship, surveillance, “Reservations” (hello, Huxley), a resurgence of absolute monarchy, and the complete dissolution of our current political world. Gender is only one of many axes on which it presents a disorienting mixture of things we long for and things we dread. It’s not an easy read, not a comfortable read, not a safe read. For many (myself included) it’s a painful read. The more you love the good aspects of this future (and I love them dearly!), the more painful it is seeing the bad ones mixed in with them. I sometimes say Terra Ignota is the opposite of beach reading. And right now it’s especially difficult because, with only two books out, it isn’t finished, and a lot of things (especially with what path forward this world will take to address its problems with gender) are absolutely unresolved.

It’s also a harder read, I think, than pure dystopia. When we read 1984, and The Handmaid’s Tale, and V for Vendetta, and The Hunger Games, we know these worlds are terrible. We the readers, the author, and the characters can all cry out together in one voice: “No!” Something like Brave New World is more difficult, because there, amid the things we find abhorrent, we are forced to admit that we would be happier, in a pure pleasure-center-synapses-firing-per-lifetime sense, if we lived in Huxley’s world than in our own. That’s a painful thing to admit. But Huxley’s world strips away so much we value more than happiness that we can still cry out together: “No!” But what if it stripped away even less, and gave us even more? (ADDENDUM: see my 2021 essay on hopepunk for an expansion of this idea.)

By most metrics of how we evaluate civilizations, the civilization in Terra Ignota is the best era humanity has experienced in Earth’s history. It has no war, no poverty, no hunger, very little crime, very little disease, very little labor, long life, amazing toys and games, spectacular future cities, unprecedented political self-determination, no homophobia, no ecological problems or pollution, less racial tension, genuinely less gender inequality even though some lingers, and kids take field trips to the Moon. But it also has deep, deep flaws—not as deep as Brave New World, but deep. The series keeps coming back to a pair of questions, asked in different ways by several core characters: Would you destroy this world to save a better one? And its opposite: Would you destroy a better world to save this one? These aren’t questions about having two planets or two realities and blowing one up, they’re questions about history, and progress. Will the characters risk destabilizing this flawed-but-best-yet age of human civilization, risking the return of catastrophe and violence, in hopes of someday making an even better world? Or will characters try to prevent this society from changing to preserve how nearly-wonderful it already is? Destroying the possibility of a better future world to avoid endangering this already very good one? These are questions no utopia or dystopia can ask—only a hybrid of the two.

“The Two Carlyles” character portrait by Atiglain, one of their many gorgeous images of the Terra Ignota cast which capture the complexities of the characters’ engagement with gender throughout the series.

So that’s Terra Ignota’s gender project in a (rather lengthy) nutshell. I hope everyone will enjoy reading on to later volumes where the gender pronouns are disrupted even more, presenting new challenges and instabilities, and where we get to see this future society come face-to-face with its lingering gender issues, and seek a good path forward. And I hope readers will be patient as the four books come out. Some novel series are episodic, each adventure completing before the next, but some, like this one, really are one project so complex it can’t be told in 140,000 words. It needs 560,000. The society of Terra Ignota will have to face its newly-unsilenced gender issues, and its solution cannot be stasis, nor can it be reversion to the old binary. But, just as real world reform movements are shaped by events—disasters, recessions, crises, wars—I want to show how this one could be shaped by events, and take a different shape depending on those events. And those events need a lot of pages to be told.

Thank you for reading, and I hope you will continue to read and enjoy Terra Ignota, but I hope above all that many of you will go on to write your own new works (fiction and nonfiction) addressing gender, and these ideas, and others. Because the biggest goal is that discourse continue!

(Want to see more recent discussions? See my guest post on Nine Bookish Lives which asked me here in 2021 to discuss Terra Ignota and the question of “a future that doesn’t see gender.”)

November 26, 2021

Perhaps the Stars Essay Roundup plus AMA best-of: Religion & Utopia in Terra Ignota

Hello, friends! Quick post today to say three things:

I am (barring emergencies) going to Worldcon in DC this December! It looks like my recovery/therapy should be just enough to try it, my first venture out to an event since the onset of the new problems, but the doctors are encouraging! It will be wonderful seeing people again!I recently did some more guest blogging as well as an online discussion for CUNY of world building and social science, along with my good friend Jo Walton, and others including Henry Farrell, Paul Krugman, and Noah Smith. The links are below! The one I’m most excited by is the Hopepunk essay.I recently did two AMAs, one in summer and one this week, and I thought I would re-share some of the most interesting questions/answers here for you to enjoy. Below I’m sharing two to start, touching on religion and utopia in Terra Ignota, and I’ll share more in the coming weeks. I hope you enjoy!Recent Posts & Pieces:Guest Post: Before We Go: Hopepunk, Optimism, Purity, and Futures of Hard Work <= this one is super great!Guest Post: Nine Bookish Lives: A Future that (Thinks it) Doesn’t See GenderGuest Post: Books, Bones, and Buffy: Octopus Rights and Imaginary Civil Rights AlliesVideo Panel: CUNY: Imagining the Future: Science Fiction and Social ScienceGuest Post: Track of Words: Q&A Ada Palmer Talks Terra IgnotaEssay: Uncanny Magazine: Expanding Our Empathy Sphere Using F&SF, a HistoryRecent Reddit AMA about “Perhaps the Stars” = 60+awesome questions! Many spoilers but all under spoiler tags.Q: Is Terra Ignota a utopia?My ideal is when readers debate it being a utopia or not, which aspects of it do seem utopian and which seem bad or even dystopian. I intentionally made a mixture: it has a twenty hour workweek, a 150 year average lifespan, general prosperity, unprecedented political self-determination, you can live with your friends, there’s been peace for 300 years… and it has censorship, severe religious restrictions, weird silencing of gender, tension over land and rents, various political strife and prejudices, and other flaws. It’s wonderful how often a pair of friends will read the book and it will feel dystopian to one and utopian to the other. The silencing of religion makes some people say, “Yay! My super-religious parents would have to shut up and theocrats would be kept out of politics!” while the same makes others say, “Wait, I couldn’t have a passover dinner or a religious wedding without state supervision?!” Similarly the silencing of gender makes some readers feel like it would be ideal, making everyone stop gendering each other and use ‘they’ for all, while other readers feel like suppressing gender expression would be terrible and prevent them from feeling like themselves. It’s often the conversations between people for whom the world feels great or very-not-great that get richest, something I intended to help show how we need to think carefully about social change if we want to make a world that works for everyone. My real goal was to make a world which would feel to us as I think our present would feel to Diderot or Voltaire: some things are amazingly much better especially medicine and lifespan and daily tech; other things are weirdly confusing like (in the Enlightenment case) clothes that would seem to them as if we’re naked all the time, and social class working totally differently; other things are depressingly familiar like, for Voltaire especially, the campaigning Voltaire did against religious intolerance, torture, and anti-vaccination movements (he was a smallpox innoculation proponent and fought with antivaxxers in the 1700s!) the continuation of those problems still being issues would be weirdly depressing. That mixture is what I was going for: better in a lot of ways, worse in a few, in others just weird and confusing. Since that is really what the future is likely to be to us.

Q: Why does everyone (in Terra Ignota) assume there’s only one god?So, short answer I don’t, and they don’t. This is a space where I think Mycroft’s own frequent discussions of Providence and a singular ‘Peer’ are overshadowing for you the details we learn about everyone else’s. Remember that Mycroft says in Seven Surrenders that he and Saladin were explicit atheists before his all-important encounter with you know who, and that while Mycroft has unitary ideas about Providence he also lenses them through Greek polytheism. Also recall that in the descriptions of sensayers especially in Too Like the Lightning it specifies that they consider atheism a belief system to be studied and discussed in all its pluralness and richness alongside the others, so sensayers are studying atheism among all the systems they study, and it’s just as diverse and complex, many different variant atheisms, than the others, all of which also enters the dialog with a sensayer. Having sensayer sessions isn’t about pushing people toward any particular belief, but facilitating people having an examined set of ideas, and making sure that everyone encounters many different systems, including several variant atheisms alongside a variety of theisms. Also important to note that, apart from the King of Spain and those close to JEDDM, the only other people whose beliefs we specifically hear about are the ones JEDDM encounters in the Saneer-Weeksbooth bash’house on pages 196-7 of Too Like the Lightning, one of whom is exposed as Catholic but the other as a believer in karma; belief in karma is definitely not the same thing as monotheism, and Carlyle tells Bridger on page 118 of Too Like the Lightning, “People have a lot of different ideas of different ways that reincarnation and karma might work,” and again most (though not all) belief systems that include reincarnation and/or karma are not monotheistic. So there’s a lot of complexity, but we see forefronted most the headspace our narrator is in, and the monotheistically-structured systems at Madame’s, precisely because they’re being *inappropriately* brought out in public while the properly-handled ones are silent, i.e. the many characters whose beliefs we don’t know because they’re correctly following the taboo. In other words, we are only seeing explicitly the religion that’s being done “wrong” by the metrics of the culture, and that one is dominated by Madame-influenced quasi-Catholic monotheism, but we see many many hints of the others in different corners of the text. Meanwhile, if you’re interested in a more complex dive into polytheism & religious pluralness in the Terra Ignota future, then I think you will enjoy Perhaps the Stars.

October 8, 2021

Medical Leave Reflections plus Empathy Sphere Essay

[image error]Good news first, I have a new essay out in Uncanny Magazine, “Expanding Our Empathy Sphere Using F&SF, a History,” where I talk about my term ’empathy sphere’ meaning the collection of beings we consider coequally a person with ourselves, something which historically has expanded over time, and which is useful in thinking about why when we read old utopias, like More’s Utopia, or early SF utopias, they often don’t feel utopian to us anymore if they don’t have freedom for groups that are inside our empathy sphere but weren’t inside More’s (like lower classes, women, certain races, clones, A.I.s etc.). It’s a useful analytic term and one several people have asked me to write about, and I also give a history of how SF has helped expand this sphere over time. I hope you enjoy reading it!

Less good and more personal news next, my health has taken a bad turn, bad enough that I have taken medical leave and had to cancel my fall teaching. My medical team is still running tests (U Chicago has an exceptional hospital), and they don’t think it’s life-threatening, but it’s probably a circulatory system issue, with symptoms including severe dizziness, faintness, stumbling & falling, all of which make it very hard to do anything, including teaching. They’re still running tests, and generally hopeful that things will improve, but on a scale of months, not weeks or days. I hope to be well enough to teach in spring. As for writing, I’m doing some, since one of the hard things in this situation is to keep my morale up and nothing nothing nothing makes me happier than writing, but it’s still being slowed, alas, though may pick up a bit as the glut of start-of-leave tasks diminishes.

So I wanted to share some reflections on this.

One is that it is amazing how much of the resistance to taking medical leave came from me, not others. Even when friends, colleagues, disability staff at the university, and family were all encouraging it, even when I confirmed my employer policies meant I could do it w/o a bad hit to income etc., even when I was in the doctor’s office and the doctor checked a couple things and the first words out of her mouth were, “Well, you can’t work!”, even when the doctors took it so seriously they wouldn’t let me walk out of the office but insisted I wait for a wheelchair, I still immediately started protesting about, “Well, if I teach remotely from lying down… but this course is special… but if I have X accommodation…” etc. arguing back even against such reasonable arguments as, “Your body is failing to deliver oxygen to your brain! You know what you need to do anything?! Oxygen for your brain!” Nonetheless, it took many days, much encouragement, and many repetitions of exhaustion & collapses for me to decide that, yes, everyone urging me to take medical leave did indeed mean I should take medical leave. (Important principle: in teaching all courses are special/unique, if you make exceptions for that you’ll never stop making exceptions.)

Where did my resistance to taking medical leave come from, when I was in the extraordinarily fortunate position of my employers, doctors, and family all being 100% supportive? (a rare and lucky thing). Partly it came from not wanting to let others down, partly from not wanting to admit to myself that it was serious, but a big part of it also comes from narratives, from The Secret Garden, from Great Expectations, from a hundred other narratives, some classic some recent, in which chronic illness/weakness/invalidness is all in one’s head, or where it’s “overcome” by force of will or powering through the pain, so that even in the fortunate case where everyone around me was being supportive and great, those narratives of powering through were unconsciously deep inside me feeding my resistance to accepting that my doctors and employer aren’t exaggerating when they say, “Don’t work.” This connects to something I discussed in my second-most-recent Uncanny essay, on the Protagonist Problem, that it’s very important to have a variety of narratives and narrative structures, and it can do real harm if one type of narrative or structure dominates depictions of a topic. Some versions of this have been discussed a lot recently: back pre-Star Trek, when close to 100% of black women depicted on TV were housemaids, it did harm by reinforcing bad stereotypes & expectations; similarly today when a very high percentage of immigrant characters depicted on TV are shown committing crimes, it feeds bad expectations. In the Protagonist Problem essay I argue that it also does harm when a large majority of our stories show the day being saved by individual special (often chosen one or superpowered) heroes, since it feeds a variety of bad impulses, including the expectation that teamwork can’t save the day, and feelings of powerlessness if we don’t feel like heroes; the argument isn’t that protagonist narratives are bad, it’s that protagonist narratives being the vast majority of narratives is bad, because any homogeneity like that is bad, just as it’s important for us to depict many kinds of people being criminals on TV, not a few kinds overrepresented and others erased.

Image from one of many adaptations of “The Secret Garden”, showing the chair the audience hopes/expects he will soon no longer need, and the very special friends whose efforts (more so than his) will make the magic happen.

Thus, for disability, we also have a problem that depictions of disability tend to repeat a few stock narratives, not one but three really, which together drown out others and dominate our unconscious expectations. One form is is the disabled/disfigured villain, a holdover from pre-modern ideas about Nature marking evil with visible indicators (and virtue with beauty). Another is a person falling ill and dying, a tragedy, which ends up focusing on the friends and loved ones who help along the way, or who survive. Another is ‘inspiration porn’ (David M. Perry has great discussions of this) which has a few varieties but tends to focus on how heroic an abled person is for helping a disabled person achieve a thing (like Secret Garden where she gets him out of the chair) instead of on the disabled person’s achievements/experience, or to present “Look a disabled person did a thing!” but in a weirdly dehumanizing way, the same way you would write “Look, this monkey can play chess!” All of these make people resistant to accepting the label disabled, since, even though it’s really useful once you have (I had trouble for a long time) we associate it with being morally bad, being doomed, or being helpless and dehumanized.

The disability narrative most relevant in my recent situation, though, are the stories of ‘overcoming’ disability, where a person is either cured (through their own efforts or others’), or works hard and pushes through, so the disability becomes a problem of the past, that has been left behind. This often-repeated narrative (present in fiction and nonfiction) encourages the attitude of seeing disability’s disruptions to life as temporary and surpassable. It means that, when I get a new diagnosis, my first thoughts even this many years into having chronic illness, are always about how long it’ll be until I overcome it, what I need to do to get past it, the expectation that it’ll be normal by spring/summer/December/whatever. This often leads me to delay by weeks or months or longer taking steps to, for example, adapt my home to be more comfortable (like getting a lap desk so I can work lying down), and other changes dependent on expecting the condition to be here to stay. I think, as a culture, we really hate telling stories about illnesses and disabilities that are here to stay.

I remember a conversation with a friend once about a situation where a medication good at treating their particular condition was taken off the market, and the parents of a kid with the condition contacted my friend to ask how to advocate or find other ways to get more of the medication, and the friend had to keep saying no that wont’ work, no you can’t get it, no you really can’t get it, no your doctor can’t write a special note, until finally they asked directly, “So what do we do now?” to which my friend answered, “Accept a lower quality of life.” That phrase crystalized things for me. I think in many ways no ending is scarier for us in narrative than accept a lower quality of life. It isn’t a one-time tragedy like death, we have good narrative tools to write tragedy, and to transition focus to the characters who live on, commemorate, remember. Accept a lower quality of life in a story means losing, giving up, surrendering, all the things we want our brave and plucky characters to never do, and then having to live with every day being that much worse forever. It’s neither a happy ending nor a tragic ending, it’s a discouraging ending, and we rarely tell those stories.

All Creatures Great And Small, part of the PBS comfort viewing of my childhood.

I vividly remember the first story like that I ever met, it was a James Harriot All Creatures Great and Small story, about a man whose family had been coal miners, who really wanted to farm, and bought a farm, and worked tirelessly to do a good job, and was a really nice person and always kind and earnest (unlike a lot of the characters in the stories), but then his cows got sick and James tried everything he could to cure them but it didn’t work, and then the farmer came to tell him, with a calm demeanor, that he was selling the farm and had always promised his father he’d go back to coal mining if “things didn’t work out” (coal mining which in the 1920s-30s meant a much shortened life expectancy as well.) James realizing how huge this was (accept a lower quality of life) despite so many efforts said, “I don’t know what to say,” and the farmer answered, “There’s nothing to say, James. Some you win.” I still tear up just thinking of that scene, the cruel unspoken and some you lose applied to a whole long life-still-to-come, every day of which would be worse, and there was no other way. A big part of modern advancement is about avoiding there being no other way–offering insurance, social safety nets, appropriate grants–but it’s also an important type of story to tell sometimes, and one I really needed some examples of. Why? Because those stories, those phrases in my memory (some you win, and, accept a lower quality of life) are not where I think I am now, I’m still working hard on treatments and therapy etc., but I needed to have them in my palette of expectations of things that could be the case, to help me plan. I needed those at the start of term to get out of the, “But surely it’ll get better in a couple weeks if I work hard,” mindset to the better attitude of, “The doctors don’t know how long this will last, I’d better plan in case it lasts a long time.”

If the only outcomes in our expectations are (A) powering through and it gets better, or (B) death/villainy/helplessness-forever, none of those archetypes will give us the sensible advice that it’s wise to plan long-term just in case there is a long-term thing that impacts quality of life. Because today a lot of those can be addressed with adapting tech/stuff/habits. I put off buying a lap desk for 2.5 months this summer, struggling to work lying down, since I didn’t want to waste the money if I was about to get better. But having a lap desk and turning out not to need it is much better than needing one and grinding on without. I also put off adapting the area around my bed to optimize for work, put off getting the new screen which finally today (Oct 7, I started wanting this in July!) got installed so I can have multiple monitors while lying down. I put off realizing that instead of watching chores pile up expecting to catch up when I got better, the household needed to discuss and make changes to reduce the total load of chores (simpler meals, paper plates, self-watering planters, planning! Also: thank you so much Patreon supporters, you made my new lying-down desk and canes and such possible!!).

I have to wear compression socks now, and I just got one pair at first and wore it for 2 months as it got grungier and grungier, always thinking “Won’t be long now!” until the doctors said clearly, “We don’t know that!” and then I bought more pairs with FIRE on them and now I like my fire socks and hate having to wear them way less! Morale is as important an adaptation to make in one’s home as mobility!

The some you win stories are extremely sad and shouldn’t become our dominant narrative, but they need to be in the mix, one color in the color wheel, to help people who do face disability to weigh the odds better, and not think well, in 90% of stories I know the person gets better so probably I’ll get better and this [desk/ screen/ cane/ adaptation] is likely to be a waste of money. Because you now what’s a good thing even if the end of one’s real life story is accept a lower quality of life? Accepting a quality of life that’s only 5% lower instead of 20% lower because you’ve adapted your home/ routine/ desk/ fridge/ breakfast routine etc. to mitigate as much of the negative impact as you can. So here I am in what is probably the best possible lying-down desk, writing and producing more than nothing, but I sure would’ve produced more over the last few months if I’d done this sooner. And I also would’ve been a lot more willing to say “You’re right I should take medical leave,” if I had believed my odds of recovering quickly were, say, 50/50, instead of, as narrative tells me, expecting that if I tried hard it was certain that I’d quickly power through (and that if I didn’t recover quickly that heralded either moral weakness, helplessness, or death, three things our minds work very hard to resist). A broader mix of disability narratives whispering in the back of my unconscious mind, telling me there might be many outcomes and I should plan for many outcomes not just for the best, would have done so much good–that’s why we need variety.

As a coda to this discussion, chatting about it with Jo Walton, she pointed out that both my examples of accept a lower quality of life stories are nonfiction (Herriott’s fictionalized from real life, the other just real life), and that after she and I first discussed the Herriott story she tried hunting for examples of that kind of story far and wide but basically never found them, that she often found it as “a Caradhras, a mountain you can’t get over so you go under, never the end.” But recently she found several examples in the work of the extremely obscure and neglected Victorian writer Charlotte M. Yonge; it’s great to find one, but also to have confirmation from a voracious reader about how rare such narratives genuinely are.

As a coda to this discussion, chatting about it with Jo Walton, she pointed out that both my examples of accept a lower quality of life stories are nonfiction (Herriott’s fictionalized from real life, the other just real life), and that after she and I first discussed the Herriott story she tried hunting for examples of that kind of story far and wide but basically never found them, that she often found it as “a Caradhras, a mountain you can’t get over so you go under, never the end.” But recently she found several examples in the work of the extremely obscure and neglected Victorian writer Charlotte M. Yonge; it’s great to find one, but also to have confirmation from a voracious reader about how rare such narratives genuinely are.

Now, my other reflection is on academia not disability things.

When I finally decided on taking leave I joked to myself, “For academics, ‘vacation’ means when you do the work you really want to do, and ‘medical leave’ is when you actually vacation.” But the reality is that even medical leave I’ve been finding myself doing minimum four hours of academic work a day, sometimes much more. It has been an interesting chance to see, both which specific parts of academic work absolutely can’t be cancelled or handed off to others, and just on the sheer volume of time that academics are required to give to things which are neither teaching nor research. Letters of recommendation wait for no man, ditto letters for other scholars’ tenure files, and mentoring meetings with Ph.D. students about their urgent deadlines; it’s one thing to set aside one’s own agenda but another to neglect things that other people really depend on. So here I was on full disability leave, with all teaching and research obligations on hold, something my university was quickly able to give, and yet I found myself working intensively from waking until dinnertime and still falling farther and farther behind even when the only work I did was letters of recommendation and inescapable paperwork. In other words, at least when rec letter season is upon us, the paperwork and mentoring parts of academia are pretty close to a full 9-to-5 job even without teaching or research! And that is for someone tenured at U Chicago, one of the most privileged teaching positions in the world, with a light load at a very supportive university.

As one friend put it, “I’m not a teacher, I’m a full-time e-mail answerer,” another, “I teach for free, it’s the grading and admin they pay me for,” another, “You can either produce research or keep up with email, but you can’t do both.” We need to factor this in as we think about how academia functions and what reforms to push for, and into how we teach Ph.D. students since things like email skills and time-management skills are absolutely essential to teaching and research when they need to be balanced basically like hobby activities squeezed into the corners of time we can scrape out around the full-time job of admin. It doesn’t have to be this bad. Possibly the problem is best summarized when I was talking to people about a high-level search committee (i.e. hiring at tenured full professor level instead of junior level) and they said they weren’t going to ask for letters of recommendation until they got to the short list of finalists and would only ask for letters for those few, not everyone, “Because we want to respect the time of the important people writing the letters.” Subtext: we don’t respect the time of the less-high-status people writing the many hundreds more letters needed for junior hires. I genuinely think every academic field would produce another 80+ books per year if we just switched to only requesting rec letters for finalists instead of all applicants, and that’s just one example of a small change. In sum, anyone near academia needs to acknowledge that the real pie chart of academic work is depicted below, that we need to plan for that and remember that small changes to self-care or workflow (just studying up on gmail tag and shortcut things for example) can make a huge difference to reducing the unreasonable load and avoiding burnout, and above all that we should always remember that phrase–respect the time of the people doing X–when we plan how to organize things (syllabus, meetings, forms, applications, committees, etc.). And I’m sure a lot of this applies far beyond the academic world as well.

Meanwhile, between recommendation letters I can’t get out of writing, plus disability paperwork, doctor’s appointments, and working on getting my home adapted so my quality of life is diminished by a little instead of a lot in my present state, I’m definitely working-rather-than-resting more than 40 hours a week, and that’s a pretty typical illness experience. It’s good to know that going in, accept it, plan for it, carve out time for the inescapable tasks and to think of adapting the home as time-consuming (or something we should ask for help with!) Otherwise it’s very easy for a week, or month, or three months of ‘rest’ to be not at all restful, and the hoped-for ‘recovery’ to remain elusive. I still have three months of leave before me and I’m definitely leveling up at how to make my leave actually be leave (delegating, adapting things, finding others to write letters when possible) but learning how to make leave actually be leave, and rest actually be rest, is definitely a skill one must level up at, and I think if we understand that it’s a skill (and perhaps tell stories about it?) we’ll be better at realizing we need to actively work to learn it when we (or loved ones) need that skill.

So, for now, I’ll be focusing on rest, and doctor’s appointments, and home adaptation, and things to keep my morale up, and writing (keeps morale up!), and getting ready for the release of Perhaps the Stars (!!!!!!!) but I hope these reflections are helpful, and many thanks to everyone who’s been supportive & helpful throughout. I’ll see you soon when I’m either (A) better or (B) fully adapted to a partly-but-minimally-lower quality of life.

And if you enjoy my writing don’t forget about the Uncanny essay: “Expanding Our Empathy Sphere Using F&SF, a History.”

August 13, 2021

Barbie Career of the Year as a Window on Centrist Feminism

First, I’m excited to announce that you can now pre-order the first segment of the new cast recording audiobook of Terra Ignota that’s being done by Graphic Audio. I’m really excited about this new audio set, which is doing the whole series broken down into volumes so this first release is the first half of book 1. I’ll write about it at greater length soon, but what I love is how the different voices with their different accents make you so much more aware of the global/international nature of the characters and setting, and the amazing director Alejandro Ruiz worked with me on some really exciting experiments with gender and casting, casting a lot of roles against what one might expect, so that the voices and physical descriptions and pronouns are all mismatched, enhancing the way Mycroft’s strange use of gender in the narration disrupts the reader’s perception of character gender, inviting the reader reflect on how perceived gender affects our feelings toward characters. We also got to do some really great representation in the casting, including not only race and nationality, but also a fantastic nonbinary performer doing Sniper and a brilliant trans woman doing Carlyle. I’ll reflect more later on but I’ve stayed up irresponsibly late more than once being unable to stop listening to the audio files, so if you enjoy the books and enjoy audiobooks I think you’ll love them! (Though the best of all possible Terra Ignota experiences definitely also involves listening to the Derek Jacobi audiobook of the Fagles Iliad right before you read book 4…)

First, I’m excited to announce that you can now pre-order the first segment of the new cast recording audiobook of Terra Ignota that’s being done by Graphic Audio. I’m really excited about this new audio set, which is doing the whole series broken down into volumes so this first release is the first half of book 1. I’ll write about it at greater length soon, but what I love is how the different voices with their different accents make you so much more aware of the global/international nature of the characters and setting, and the amazing director Alejandro Ruiz worked with me on some really exciting experiments with gender and casting, casting a lot of roles against what one might expect, so that the voices and physical descriptions and pronouns are all mismatched, enhancing the way Mycroft’s strange use of gender in the narration disrupts the reader’s perception of character gender, inviting the reader reflect on how perceived gender affects our feelings toward characters. We also got to do some really great representation in the casting, including not only race and nationality, but also a fantastic nonbinary performer doing Sniper and a brilliant trans woman doing Carlyle. I’ll reflect more later on but I’ve stayed up irresponsibly late more than once being unable to stop listening to the audio files, so if you enjoy the books and enjoy audiobooks I think you’ll love them! (Though the best of all possible Terra Ignota experiences definitely also involves listening to the Derek Jacobi audiobook of the Fagles Iliad right before you read book 4…)

This topic is very far from my usual bailiwick but important in its odd way, expanding on a Twitter thread from 2020. I am not, nor have I never been, a Barbie collector, but I find the Career of the Year series fascinating as a metric of public attitudes toward feminism. In the broad spectrum of feminist discourse, the fringes and harsh or stinging voices are often the loudest (the progressive left & conservative right), making the Mattel Barbie team an informative contrast.

Generally Mattel’s team wants to present Barbie as a feminist trendsetter but in a centrist way, a model of forward-thinking but non-controversial feminism, and it’s fascinating to watch that metric evolve.

Mattel knows that what it includes or excludes in the Barbie line gets attention and has a political impact, and knows it’s doing and who it’s offending/pleasing, in terms of both profit-seeking and messaging, when it creates things like its new trans-friendly nonbinary Creatable World doll kits which make gender-mixing easy:

Image of the “Creatable World” doll series, showing its racial diversity and how it encourages mixing male-coded and female-coded clothing and hairstyles, with exchangeable heads with long and short hair.

But while producing something like that means Mattel is taking a stand in one sense, it’s notably not in the main Barbie line. The Barbie line itself tends to be a bit more cautious, especially with Barbie herself.

This promo for the Barbie “Fashionistas” line including variants on the square-jawed Ken face, including one with long hair, as well as a range of races and appearances, makes the argument that a range of bodies including masculine-seeming bodies can be interested in fashion and part of “We are Barbie” but is carefully not quite as explicitly trans-friendly as the non-Barbie creative kit.

Since the Barbie Career of the Year doll is designed to be the most discussed, and aims to make an impact in its claims about the attributes of an ideal female role-model, it is a fascinating reflection of what a group of decision-makers who are almost all women feel is the right focus for their annual feminist-yet-centrist message about what girls and women should aspire to. The bodily diversity of the Barbie line has been growing steadily, as shown in the image below of the 2019 line with its range of body types, racial characteristics, and disability representation, but the politics of careers is fascinating separately.

Barbie’s 2020 Career of the Year is (for the first time) not a single Barbie but a team, a Political Campaign team featuring 4 dolls: Candidate, Campaign Manager, Fundraiser, and Voter, with diverse race and body types. Interesting to compare to past Career of the Year Barbies.

I’ll give the list of past ones first, then some analysis. Barbie had already had many earlier careers, including astronaut, president, business woman, and others, but the formal Career of the Year series launched in 2010:

2010 = Computer Engineer2011 = Architect2012 = Fashion Designer2013 = Mars Explorer2014 = Entrepreneur2015 = Film Director2016 = Game Developer2017 = no Career of the Year doll for 2017 that I can find2018 = Robotics Engineer2019 = Judge2020 = Political Campaign Team (four dolls)(2021 = Music Producer, not yet out when I wrote this thread)

A compilation image made by Mattel, selecting only some of the sequence.

Barbie has had a lot of careers over time, including earlier iterations of astronaut and president, & her 60th Anniversary Career set has astronaut, firefighter, soccer player, airline pilot, news anchor, and “political candidate.”

The WSJ did a great piece on Barbie’s history as a political figure back in 2016 when Barbie did a version running for president with a female running mate, clearly referencing Hillary’s campaign

2016 was the 6th presidency-focused Barbie, making her political career thus:

2016 was the 6th presidency-focused Barbie, making her political career thus:

Note that 1992, 2000, 2004, 2016 & 2020 all candidates, while 2008 & 2012 are Presidents, i.e. already victorious rather than running, an interesting choice for the window right after Hillary lost to Obama in 08 primary.

The 2016 and 2020 political Barbies have variety in skin tone and hair color, and 2020’s has variety of body type as well, in line with Mattel’s recent changes, whereas 1992-2012 are all distinctly the original blonde Barbie moving into a political career.

But no earlier president or presidential candidate Barbie was in the Career of the Year series, which is the most visibly political moment of Mattel’s year, the Barbie choice they expect to get the most discussion and spark the most newspaper coverage etc.

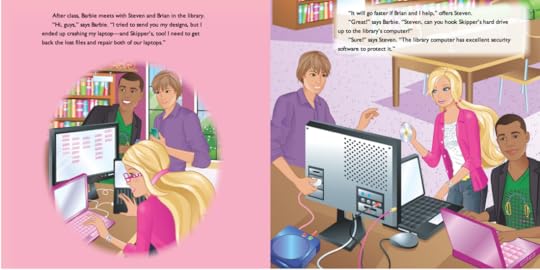

Career of the Year started as something of a disaster in 2010 when the well-meaning Computer Engineer Barbie, winner of a voting contest to pick the first Career of the Year, was launched w/ a badly-thought-through accompanying book which focused on her repeatedly messing up and needing male programmers to fix her machine (even to get rid of a simple virus!) and to turn her concept into a game.

Career of the Year started as something of a disaster in 2010 when the well-meaning Computer Engineer Barbie, winner of a voting contest to pick the first Career of the Year, was launched w/ a badly-thought-through accompanying book which focused on her repeatedly messing up and needing male programmers to fix her machine (even to get rid of a simple virus!) and to turn her concept into a game.

When Architect was next (2011) I remember thinking about the fact that (at the time) when you looked at lists of college majors by expected salary, architect was usually listed as the highest-paid major for women.

In fact the story is really cool, this great article discusses the campaign for architect Barbie, effort to convey power via her glasses & hardhat (which she never wears in the photos), & the experiments presenting her to girls to make sure the doll’s professional skill went unquestioned, unlike her computer engineer predecessor.

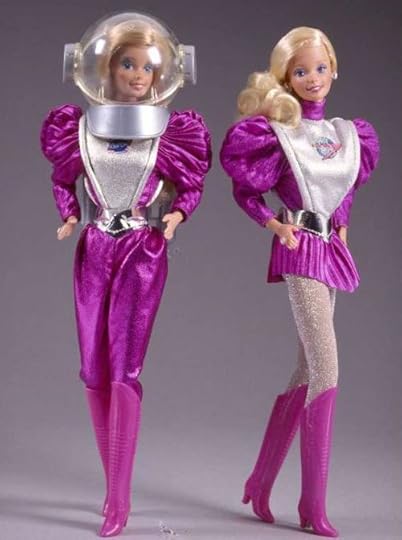

2013 Mars Explorer was the 1st mission-specific space Barbie though there had been several astronauts.

The Career of the Year Mars Explorer Barbie

She was pinker than average though less sparkly than average, and accompanied by many science facts. Below are three earlier astronaut Barbies, for contrast:

2014’s “Entrepeneur” is strangely vague, forgettable, and was much mocked at its release with headlines like “Entrepreneur Barbie will Inspire Girls to Be Vaguely Ambitious.” It was very well researched underneath, made in consultation with some major global feminist leaders like Reshma Saujani, the founder of Girls Who Code, but it struggled to get a clear concept across.

The vagueness of Entrepeneur Barbie for me is an exposure of the strained path-to-wealth archetype in our society, since it’s so much about networking, pitching, acquiring companies, buying out rivals, moving money around rather than making things; hard to describe on a box. The fact that there’s no comprehensible clear thing an entrepreneur Barbie would do or make, other than have money and move money around to make more money, is an example of how hard it is to communicate to kids how power and money really work (and how nonsensical it often is).

2015 Film Director was a clear response to discussion happening at the time about how few female film directors there were in Hollywood. She did come with several types of hair and skin tones (version options on some of these are hard to trace).

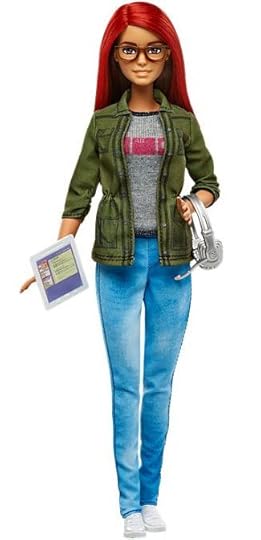

2016 Game Developer was a direct effort to redo and recover from the mistakes of the 2010 computer engineer. She (left) has one of the least pink least feminine outfits ever on a barbie, a silver (not pink) laptop and much more technical info on the box. 2010s on the right.

Here you see game developer Barbie next to her unsuccessful software predecessor:

One Casey Feisler on Flickr did this great compilation comparing the packaging for both plus for the 2018 Robotics Engineer career of the year Barbie. Note the new focus on precisely what she does herself not leaving it to colleagues.

The robotics engineer doll was very similar, still glasses and a laptop, but notable for the black variant being used in publicity images a lot more, almost 50/50 with the white version.

I’m still trying to figure out why there appears to have been no Career of the Year Barbie for 2017. I’ve looked and looked at this strange gap between the two very similar engineering dolls of 2016 and 2018. I’d love for someone to solve the mystery. It’s worth remembering that Mattel had very excitedly made their all-female presidential ticket President & Vice President pair in 2016 and seemed really invested in Hilary’s campaign to be the first female president – was it a morale thing that slowed them down for 2017?

Regardless, after 2018’s robotics engineer, Mattel exploded into the super political with 2019’s Judge Barbie, a clear and extremely not-neutral reference to the activities of RBG on the Supreme Court, and Republican-led stuffing of the courts. And as you can see in the image below, the 2019 judge Barbie, like the presidential set from 2016 and the two engineering Barbies, actively spotlighted its increased diversity in hair color and skin tone in its media:

Judge Barbie is available in a variety of different skin tones and hairstyles.

Which gets us to 2020’s Career of the Year team, the first team and, so far as I can tell, the first politically active Barbie that isn’t focused on the presidency specifically, but could be running for congress, senate, local office, anything.

The distribution of race and body type was clearly carefully calculated, with an African American candidate, a medium-skin-toned POC-looking voter (could be Latina, First Nations, many things), and Mattel’s new heavier body type for the blonde in the role of fundraiser. It’s about teamwork, both the idea that a successful campaign requires many people beyond the candidate, & about the importance of many kinds of races, continuing Judge Barbie’s turn toward branches of government beyond the Presidency.

So many Barbie careers are about celebrity (actress, singer, rapper, princess) & the Presidency is a celebrity position (more so under Trump) so the break with celebrity & focus on non-famous staffers & voters & less spot-lit races is a bigger change for Barbie than it may seem. Mattel’s goal is clear, their contribution to the turn-out-the-vote movement, but I think the attention to teamwork and the importance of non-celebrity people, of the people who aren’t the center of attention, has a potential power beyond the political.

Careers of the Year have always been the one in the spotlight: the director, the architect, the designer, the one who steps on Mars, the president, with little discussion of being on the team, or the fact that movies, buildings, Mars missions are teamwork. So after six presidents or presidential candidates (and one VP) and many other Barbies-in-the-spotlight I hope this teamwork focus will help girls feel like they’re powerful even if they aren’t on the stage, in the spotlight, or in charge. A good message.

My 2020 summary thought: Keep it up, Mattel! This year’s team is great, let’s see more Career of the Year teams! Design teams, surgical teams, the Mission Control team, crisis intervention teams, pharmaceutical development teams, publishing teams (author, editor, publisher, publicist)!

My 2021 addendum: Barbie’s 2021 Career of the Year, music producer, is less remarkable than the last two in many ways, another iteration of Barbie with a pink laptop and headphones, which seems to be Mattel’s signature for Barbie-in-tech, though this one also has the music levels slider board:

Yet there are some interesting elements. Her range of unnatural hair colors is not the first in the career line, and is something Mattel appears to associate with tech as well as with music, but I find her ripped-knee jeans is notable since no earlier career Barbie wore anything quite so casual, except for the “voter” in the team set. Since this doll was certainly in development in 2020, that likely reflects the advance of casual-is-okay -for-work ideas in fashion in the age of work-from-home. That 2021’s doll is not a team does make sense in a world where work from home separated us so much, but it will be interesting to see if the solo Barbie continues to be a pattern. It is neat, though, seeing them once again showcase a job which is part of the fact that media is teamwork, i.e. the producer not the rockstar, similar to when Barbie the Film Director in 2015 directed girls’ attention to a different type of power in Hollywood from the many movie star Barbies of earlier Barbie decades. In a sense it’s a job which showcases teamwork even while alone, and thus very apt for 2020/2021, and perhaps a good sign for Mattel continuing to think about teamwork and plural agency even in their solo dolls. And the fact that it got much less media attention than judge or political team may mean that the forces of capitalism step in to encourage Mattel to try something bolder next year–we must never forget the $$ side of commercial political messaging.

So, what does the Career of the Year sequence show us about Barbie as a mark of centrist feminism? A few things. One is that women-in-tech is definitely a thing, far more in the minds of the organizers than women-in-STEM, since we haven’t seen biologist Barbie or epidemiologist Barbie showcased, only several iterations of tech Barbies, including software and hardware. It also shows through things like entrepreneur Barbie and architect Barbie that sometimes they look a lot at research, especially about income and what are high-paying careers, and think it’s important that Barbie encourage girls to go into high-paid professions not just exciting ones (beloved-yet-underpaid careers like teacher and nurse have been frequent Barbie careers but not showcase ones). They also sometimes run into challenges in communication, i.e. ‘entrepeneur’ is a very important concept but very difficult to communicate in a doll via clothing and accessories, as is true of many careers.

Several of the career Barbies–notably game designer and music producer–have been major steps in more casual clothing, which is a not insignificant message when we think of the target market largely including middle-class suburban mothers (parents buy the toys more often than kids, after all) who are thus expected to consider ripped knees and wild hair a respectable image for girls to aspire to. The increase in tightly-fitted-yet-somewhat-ungendered clothing, which reached its peak with the carefully-planned game designer doll, is also notable. Recalling how much fashion pressures linger in business, how many employers still expect makeup and highly feminine dress for all women, the dolls’ statement that sneakers, jeans, and a shirt and jacket whose only feminine coding lies in the tightness of their fitting and the small amount of pink on the shirt is a genuinely significant change. That 2021’s is a step more feminine in coding even as it is a step more casual is interesting when put in dialog with gender and transgender issues becoming such a hot topic in the past few years.

Several of the career Barbies–notably game designer and music producer–have been major steps in more casual clothing, which is a not insignificant message when we think of the target market largely including middle-class suburban mothers (parents buy the toys more often than kids, after all) who are thus expected to consider ripped knees and wild hair a respectable image for girls to aspire to. The increase in tightly-fitted-yet-somewhat-ungendered clothing, which reached its peak with the carefully-planned game designer doll, is also notable. Recalling how much fashion pressures linger in business, how many employers still expect makeup and highly feminine dress for all women, the dolls’ statement that sneakers, jeans, and a shirt and jacket whose only feminine coding lies in the tightness of their fitting and the small amount of pink on the shirt is a genuinely significant change. That 2021’s is a step more feminine in coding even as it is a step more casual is interesting when put in dialog with gender and transgender issues becoming such a hot topic in the past few years.

And, of course, we saw with judge Barbie and the political candidate team Barbie that a lot of people who consider themselves politically fairly neutral/centrist, including Mattel, felt that the wake of Trump’s election and the midst of the authoritarian surge of 2016-2020 was an important moment to step forward, become more active, and, for the first time in Barbie’s history, to take a semi-overt political stance, since celebrating judge Barbie in the midst of so much focus on Ruth Bader Ginsburg, is not explicitly pro-Democratic-party but it’s extremely clear the way it leaned. Many organizations that strive for party neutrality, from Mattel to the ACLU to the science journal Nature, felt that Trump’s second run was the moment to use that history of neutrality for an important end, since breaking a multi-decade string of never endorsing one party over the other makes the moment when one does speak out that much more powerful. That 2021’s doll is far less political, except for being pro women-in-tech, raises the question whether we should view the renewed projection of party neutrality as a happy return to normal, or as a scary sign that the wave of sudden political engagement sparked in 2016-20 is fading again, and that voter turnout may wane with it.

In sum, since news and social media both tend to magnify radical voices on both sides, things like Mattel’s carefully-calculated political stances can be a valuable window on the often-quieter middle, though whether it really is the middle or just attempting to claim “this should be the middle!” as the real middle moves left and right is another question. And the fact that the fashion-focused “Fashionistas” line and new sets like the glamorous bond-movie style “Spy Squad” Barbie set persist alongside our career Barbies also shows that the extremely gendered Hollywood femme fantasy side of Barbie is still just as strong in the moderate center of this particular feminine ideal as all the politically-progressive versions are (if not stronger since the fashion focused Barbie lines are usually much larger than the career sets). Of the nine dolls in the 2016 splash add below, one-third are narrative-free fashion-consumers, one-third Hollywood fanatsy babes, and one-third career role models, a telling microcosm of the imagery proportions kids are pelted with. Ongoing food for thought.

August 7, 2021

5 News Items: Podcast, Online Teaching, Gene Wolfe, Audiobooks, & Perhaps the Stars

Hello, friends – I have a proper essay underway, but short-term I have a five pieces of exciting news:

My new podcast,An online history course I’ll be teaching this fall through U Chicago’s Graham school, which isn’t free but can be taken by anyone from anywhere.My Introductions to Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun,A new Terra Ignota audiobook series is coming soon from Graphic AudioThe approaching publication of Perhaps the Stars, the fourth and final volume of Terra Ignota.First I have a podcast now!It’s called Ex Urbe Ad Astra

Partnering with my good friend and fellow author & history lover Jo Walton (more on her below), we interview fellow writers, historians, researchers, editors, and other friends, talking about the craft of writing, history, food, gelato, and other nifty topics, with some episodes of just me and Jo having the kinds of intense writing or history discussions we enjoy. You can listen for free on Libsyn, on Apple Podcasts, and YouTube. Those who support me on Patreon get new episodes early (and new ExUrbe posts early too.)

Sample Episode: Speculative Resistance with Malka Older

The episodes in this first season are modeled on the kinds of panel discussions one has at science fiction conventions, and are long (an hour plus), and since our interviewees are all so interesting! Episodes of this season will come out monthly, with occasional bonus episodes, those are the ones with just me and Jo.