The Year of Reading Proust discussion

This topic is about

Swann’s Way

Swann's Way, vol. 1

>

Through Sunday, 13 Jan.: Swann's Way

message 51:

by

Aloha

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Jan 07, 2013 06:57PM

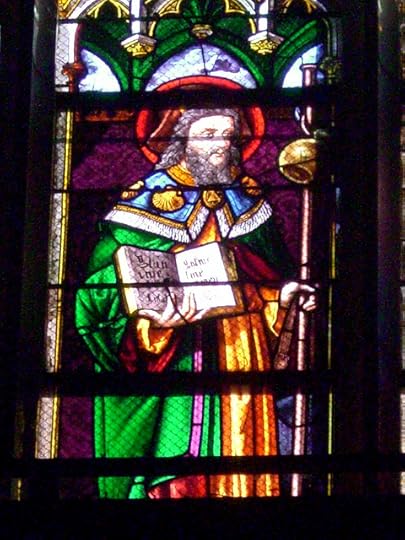

Church of Combray:

Church of Combray:

reply

|

flag

Town of Combray. This section reminds me of the part where he comes upon the cross road of the entrance of the town that reminds him of the apse.

Town of Combray. This section reminds me of the part where he comes upon the cross road of the entrance of the town that reminds him of the apse.

Madame X wrote: "ReemK10 (Got Proust?) wrote: "Had he read the story of the tea and madeleines before you offered them to him? "

Madame X wrote: "ReemK10 (Got Proust?) wrote: "Had he read the story of the tea and madeleines before you offered them to him? "I have no idea. Would it shock you to hear that we didn't get along very well?

& E..." It appears that he was intentionally being rude to you for whatever reasons. It makes for a great anecdotal story though. I hope it hasn't tainted your taste for the cookies. Also, what a lovely opportunity to go visit Illiers-Combray! I'm hoping that Nick will share the pics of his visit there. I know I enjoyed seeing the photos of Tante Leonie's house.

The passages on the steeple is beautiful, spiritual and symbolic. Anybody has a take on its' significance?

The passages on the steeple is beautiful, spiritual and symbolic. Anybody has a take on its' significance?

It's so obviously a phallic symbol, celebrated in place of the phallus as a product of Proust having to hide his sexuality from society.

It's so obviously a phallic symbol, celebrated in place of the phallus as a product of Proust having to hide his sexuality from society.Not really. Just kidding. I think it is just a celebration of something he found beautiful, made stronger by the lens of nostalgia. Also it might link into later themes. eg: for those who have read the whole thing: (view spoiler)

In addition Illiers-Combray isn't the most lively place and the church really stands out, in real life and it seems in Narrator's mind. It is slap bang in the middle of the town and the square, which must have made it the social focal point for a Catholic village of the time, which I am guessing IC was :)

Reem, I will try and share, this forums a bit tricky for pic posting. Also my computer had a bit of a hissy fit trying to export them off the camera...I snuck into the church as it was lunchtime and closed (12-14.00) for the French lunch where life shuts down. Only took a few snaps before I made my escape.

You cheeky monkey, Nick. LOL.

You cheeky monkey, Nick. LOL. I think we need to note the difference between the steeple and the spire, especially as the body of the church is significant in Proust's work. The steeple is the church tower that tapers to the point. The spire is the conical/pyramidal structure of the roof line that goes to the point.

What you said about the spire, Nick, makes me wonder what the meaning of the steeple is, since it is the steeple that "one must return..."

Note what Ruskin said:

"and their security is provided for by strong gabled dormer windows, of massy masonry, which, though supported on detached shafts, have weight enough completely to balance the lateral thrusts of the spires. Nothing can surpass the boldness or the simplicity of the plan; and yet, in spite of this simplicity, the clear detaching of the shafts from the slope of the spire, and their great height, strengthened by rude cross-bars of stone, carried back to the wall behind, occasion so great a complexity and play of cast shadows, that I remember no architectural composition of which the aspect is so completely varied at different hours of the day. [10] But the main thing I wish you to observe is, the complete domesticity of the work; the evident treatment of the church spire merely as a magnified house-roof; and the proof herein of the great truth of which I have been endeavoring to persuade you, that all good architecture rises out of good and simple domestic work; and that, therefore, before you attempt to build great churches and palaces, you must build good house doors and garret windows."

And what is in this section of Swann's Way:

...the apse, crouched muscularly and heightened by the perspective, seemed to spring upwards with the effort which the steeple was making to hurl its spire-point into the heart of heaven—it was always to the steeple that one must return, always the steeple that dominated everything else, summoning the houses from an unexpected pinnacle, raised before me like the finger of God, whose body might have been concealed below among the crowd of humans without fear of my confusing it with them...." (Moncrieff)

I misquoted and meant steeple :P so quite true. (view spoiler)

I misquoted and meant steeple :P so quite true. (view spoiler) The second quote is significant, I think.

Kalliope wrote: "Well, I have to say that with this description of the Church at Combray, I have finally encountered the Proust that I was dreading. I have had to trace back my reading several times so as to be ab..."

I agree with you at first. The description of the church started to wear on me to the point where I just started thinking to myself, please, I hope he can move on soon! Because at least when he introduces a character and their thoughts and then reintroduces the steeple it all makes more sense to me. I have a hard time finding the entirety of that description beautiful because of the fact that it became a chore to me to read it. I believe that having now gotten through it there is value in having read it and I imagine it is a backdrop for the rest of the story. This is one of these deals in longer novels such as 2666 and War and Peace I have resigned myself that I am not going to love every page of it. Of course, I may enjoy it more on a re-read after I have gotten further ahead.

I agree with you at first. The description of the church started to wear on me to the point where I just started thinking to myself, please, I hope he can move on soon! Because at least when he introduces a character and their thoughts and then reintroduces the steeple it all makes more sense to me. I have a hard time finding the entirety of that description beautiful because of the fact that it became a chore to me to read it. I believe that having now gotten through it there is value in having read it and I imagine it is a backdrop for the rest of the story. This is one of these deals in longer novels such as 2666 and War and Peace I have resigned myself that I am not going to love every page of it. Of course, I may enjoy it more on a re-read after I have gotten further ahead.

Here's some help in imagery when reading the church passages, which I agree is a significant backdrop to ISOLT. Most of these are from Wikipedia.

Here's some help in imagery when reading the church passages, which I agree is a significant backdrop to ISOLT. Most of these are from Wikipedia.Apse:

In architecture, the apse (Greek ἀψίς (apsis), then Latin absis: "arch, vault"; sometimes written apsis; plural apses) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome. In Romanesque, Byzantine and Gothic Christian abbey, cathedral and church architecture, the term is applied to a semi-circular or polygonal termination of the main building at the liturgical east end (where the altar is), regardless of the shape of the roof, which may be flat, sloping, domed, or hemispherical.

I can't find a picture of the apse of Combray. Maybe because it's ugly as Proust said, and not good picture material. So this one is the beautiful one in Wiki.

Steeple:

A steeple, in architecture, is a tall tower on a building, often topped by a spire. Steeples are very common on Christian churches and cathedrals and the use of the term generally connotes a religious structure. They may be stand-alone structures, or incorporated into the entrance or center of the building.

Spire:

A spire is a tapering conical or pyramidal structure on the top of a building, particularly a church tower....

Symbolically, spires have two functions. The first is to proclaim a martial power. A spire, with its reminiscence of the spear point, gives the impression of strength. The second is to reach up toward the skies.[2] The celestial and hopeful gesture of the spire is one reason for its association with religious buildings.[citation needed] A spire on a church or cathedral is not just a symbol of piety, but is often seen as a symbol of the wealth and prestige of the order, or patron who commissioned the building.

Steeple and spire of the church of Combray:

I'm noting the points beyond time, where time seemed to not exist. The first is the boy's bed when the world around him is like a magic lantern. The second is the church, where the mortal movement of the town revolves around it.

I'm noting the points beyond time, where time seemed to not exist. The first is the boy's bed when the world around him is like a magic lantern. The second is the church, where the mortal movement of the town revolves around it.

Yes Proust could liken his work to a cathedral but it would be rare for Frank Gehry to liken one of his buildings to the prose of Proust. However it could happen, and probably has, as language is unconstrained, you can say what you want, how you want to say it & make the reader (or writer if you're a reader response theorist) imagine any and every sort of thing in this world and beyond. But remember that the likening of architecture to language can only be done in language. See Derrida here. Language is magic and Proust is a magician.

Yes Proust could liken his work to a cathedral but it would be rare for Frank Gehry to liken one of his buildings to the prose of Proust. However it could happen, and probably has, as language is unconstrained, you can say what you want, how you want to say it & make the reader (or writer if you're a reader response theorist) imagine any and every sort of thing in this world and beyond. But remember that the likening of architecture to language can only be done in language. See Derrida here. Language is magic and Proust is a magician.The first sentence of this week's reading is short but a little marvel, qualifiers within qualifiers, and you know that Proust considered it well, so careful a writer he was, to begin a section. I reread it several times in the Davis & then in the Enright translation until I finally got to an understanding of it which may be different from your understanding and I hope it is, said the 'democratic' me.

"Combray, from a distance, for ten leagues around, seen from the railway when we arrived there the last week before Easter, was no more than a church summing up the town, representing it, speaking of it and for it into the distance, and, when one approached, holding close around its high dark cloak, in the middle of a field, against the wind, like a shepherdess her sheep, the woolly gray backs of the gathered houses, which a vestige of medieval ramparts girdled here and there with a line as perfectly circular as a small town in a primitive painting."

First, the easiest thing to do is to determine the main verb of the predicate, separating the sentence into two parts, the subject and the predicate, that which tells what the subject is or does, the verb can only be singular or compound and never complex as subjects and 'objects/attributes' can be which is where I part company with formal grammarians as I break the predicate down into this/these. The idea is not to be correct but to understand what the sentence says and how it says it and in the future to be able to use what one has learned from this breakdown. The verb is "was" the subject is "Combray" the attribute is "church" 'Combray was a church,' is the stripped down sentence, but how could a town be a church, what are the components of the metaphor? Well the rest of the sentence tells us.

What interests me is that Proust strings a series of gerunds in the predicate that modify the metaphoric equation Combray=church, "summing, representing, speaking' and finally "holding", that begins a phrase, which he further qualifies, internally one could say, by an embedded simile, "like a shepherdess…" and an embedded metaphor "the woolly gray backs of the gathered houses" in the phrase that begins with "holding".

You can see why Jean Milly says that the structure of Proust's sentences are similar to the structure of the novel.

With most Proustian long sentences, we have a simple main verb, a relatively simple subject--here qualified by a prepositional phrase/clause--and a very, very complex predicate or what I call an object/attribute of the subject. This is also true of sentences written by the two great 19th century prose stylists, John Ruskin and Walter Pater.

Eugene, to me, his grammatical usage is designed to create a revolution around a particular point. Note how the qualifiers do their job to shift perspectives from the church of Combray.

Eugene, to me, his grammatical usage is designed to create a revolution around a particular point. Note how the qualifiers do their job to shift perspectives from the church of Combray.

Bachelard and Proust:

Bachelard and Proust:I think the connection is reverie: both men valued that wonderful free-floating semi-consciousness half-awake fluid state of free association . . .

Eugene, I think you'd really enjoy Figures III. Genette on narrative theory, using Proust as his main source of examples.

Eugene, I think you'd really enjoy Figures III. Genette on narrative theory, using Proust as his main source of examples.

Nick wrote: "It's so obviously a phallic symbol, celebrated in place of the phallus as a product of Proust having to hide his sexuality from society.

Nick wrote: "It's so obviously a phallic symbol, celebrated in place of the phallus as a product of Proust having to hide his sexuality from society.Not really. Just kidding. I think it is just a celebration ..."

Nick, it might be easier to post them on twitter with the hashtag #Proust2013. Aloha, that is a beautiful photo. Lighting is superb. And lol@me for trying to give Eugene how to try and write like Proust tips. Too funny Reem!

ReemK10 (Got Proust?) wrote: "And lol@me for trying to give Eugene how to try and write like Proust tips. Too funny Reem! "

ReemK10 (Got Proust?) wrote: "And lol@me for trying to give Eugene how to try and write like Proust tips. Too funny Reem! "No difference from me giving tips on the church, Reem!

Cassian wrote: "Bachelard and Proust:

Cassian wrote: "Bachelard and Proust:I think the connection is reverie: both men valued that wonderful free-floating semi-consciousness half-awake fluid state of free association . . ."

I'm halfway into the Bachelard book, and it's terrific. Definitely have to go back and take notes.

I am curious if anyone understood the meaning of this passage:

"Its memorial stones, beneath which the noble dust of the Abbots of Combray who lay buried there furnished the choir with a sort of spirtual pavement, were themselves no longer hard and lifeless matter, for time had softened them and made them flow like honey beyond their proper margins, here oozing out in a golden stream, washing from its place a florid Gothic capital, drowning the white violets of the marble floor, and elsewhere reabsorbed into their limits...." p80 of ML edition

Is he saying that the bodies that were buried have decayed into a honey like substance? And if so, they actually then flowed upward? I read this part this morning and am still puzzling over it. Then later on p82 when he was describing the windows and tapestries (I think):

... - then next instant it had taken on the shimmering brilliance of a peacock's tail, then quivered and rippled in a flaming and fantastic shower that streamed from the groin of the dark and stony vault down the moist walls...

which I could not help but think he was comparing to urnination but why!

I think my favorite part of what I have read of this section so far is when he says the church has four dimensions, one being time and the notion of the building and grounds surviving the epochs.

"Its memorial stones, beneath which the noble dust of the Abbots of Combray who lay buried there furnished the choir with a sort of spirtual pavement, were themselves no longer hard and lifeless matter, for time had softened them and made them flow like honey beyond their proper margins, here oozing out in a golden stream, washing from its place a florid Gothic capital, drowning the white violets of the marble floor, and elsewhere reabsorbed into their limits...." p80 of ML edition

Is he saying that the bodies that were buried have decayed into a honey like substance? And if so, they actually then flowed upward? I read this part this morning and am still puzzling over it. Then later on p82 when he was describing the windows and tapestries (I think):

... - then next instant it had taken on the shimmering brilliance of a peacock's tail, then quivered and rippled in a flaming and fantastic shower that streamed from the groin of the dark and stony vault down the moist walls...

which I could not help but think he was comparing to urnination but why!

I think my favorite part of what I have read of this section so far is when he says the church has four dimensions, one being time and the notion of the building and grounds surviving the epochs.

I’m new to Proust and very excited to be part of the group. I began Swann’s Way in December and by the beginning of the new year was several weeks ahead, so I decided to put it down for a bit and read something completely different just for a change of pace. Have always been a big Kingsley Amis fan, but had never read Martin Amis, so I picked up his latest. Well, it turns out I’m not such fan of Martin Amis. Though the writing is crisp and sometimes funny, I found the novel to be disturbingly devoid of real emotional content. Plenty of snark, but no soul. It really bothered me, and I had trouble finishing the book, which is unusual for me. Returning to Proust was such a relief. Real feelings, sympathy, real humanity. I didn’t realize how captivated I was by the atmosphere of Swann’s Way. Now I’m pretty sure that at least the unusual strength of my negative reaction to the Martin Amis was due in part to having been immersed in the world of Proust for a few weeks. Wondered if other readers are finding that the Proust experience is affecting them in unexpected ways?

I’m new to Proust and very excited to be part of the group. I began Swann’s Way in December and by the beginning of the new year was several weeks ahead, so I decided to put it down for a bit and read something completely different just for a change of pace. Have always been a big Kingsley Amis fan, but had never read Martin Amis, so I picked up his latest. Well, it turns out I’m not such fan of Martin Amis. Though the writing is crisp and sometimes funny, I found the novel to be disturbingly devoid of real emotional content. Plenty of snark, but no soul. It really bothered me, and I had trouble finishing the book, which is unusual for me. Returning to Proust was such a relief. Real feelings, sympathy, real humanity. I didn’t realize how captivated I was by the atmosphere of Swann’s Way. Now I’m pretty sure that at least the unusual strength of my negative reaction to the Martin Amis was due in part to having been immersed in the world of Proust for a few weeks. Wondered if other readers are finding that the Proust experience is affecting them in unexpected ways?

Jeremy wrote: "I am curious if anyone understood the meaning of this passage:

Jeremy wrote: "I am curious if anyone understood the meaning of this passage: "Its memorial stones, beneath which the noble dust of the Abbots of Combray who lay buried there furnished the choir with a sort of..."

I can check the French in a few hours and see whether I can add anything to this, although, as I said in an earlier post, I found the church section difficult.

Jeremy wrote: "I am curious if anyone understood the meaning of this passage:

"Its memorial stones, beneath which the noble dust of the Abbots of Combray who lay buried there furnished the choir with a sort of..."

The memorial stones - gravestones - have been warped by time. They've been worn into soft and fluid shapes that look poured.

The peacock's tail is light coming in through stained glass windows. A "groin vault" is a technical term - where two barrel-vaulted ceilings cross perpendicularly.

"Its memorial stones, beneath which the noble dust of the Abbots of Combray who lay buried there furnished the choir with a sort of..."

The memorial stones - gravestones - have been warped by time. They've been worn into soft and fluid shapes that look poured.

The peacock's tail is light coming in through stained glass windows. A "groin vault" is a technical term - where two barrel-vaulted ceilings cross perpendicularly.

Jeremy wrote: "I am curious if anyone understood the meaning of this passage:

Jeremy wrote: "I am curious if anyone understood the meaning of this passage: "Its memorial stones, beneath which the noble dust of the Abbots of Combray who lay buried there furnished the choir with a sort of..."

As Kal mentioned in a previous post, French helps us out a little because it supplies us with genders, to distinguish a little between all the different 'theys' and 'thems'. It's not the bodies that time has rendered soft and honey like, but the stones. The stones are oozing beyond their squaring, washing out in a stream. Lots of images of flow, associations with water moving. The church is a living thing, not hard immoveable stone.

Lots of water, yes. I'm not sure, in your second quote, where the translator got the idea of a 'groin', which, doubtless, is suggesting the image of urination. I'm getting blue light that falls like rain from the heights of the vault, then the next bit is the cave, so again, water and then something natural rather than a church.

Apart from the fact that his parents are carrying prayer books, there's never any feeling that the church is anything but a beautiful living thing, rather than a place of devotion to god. Oh, except for Mme Sazerat, but the petits fours seem more important than what she's actually doing on her knees.

Kalliope wrote: "Jeremy wrote: "I am curious if anyone understood the meaning of this passage:

Kalliope wrote: "Jeremy wrote: "I am curious if anyone understood the meaning of this passage: "Its memorial stones, beneath which the noble dust of the Abbots of Combray who lay buried there furnished the choir..."

This one confused me too, but I think it's the marble of the tombstones that is flowing like honey. Note that the engraved letters are sliding and distorting with the flow. I wasn't aware that marble could flow like honey; I even thought of trying to do a Google image search on this phenomenon to see if I could find an example.

Edited to add: Oops, this one's already been answered. I should have refreshed! I'm not used to Goodreads threads moving this fast.

"but, either because a ray of sunlight had gleamed through it or because my own shifting glance had sent shooting across the window, whose colours died away and were rekindled by turns, a rare and flickering fire—the next instant it had taken on the shimmering brilliance of a peacock’s tail, then quivered and rippled in a flaming and fantastic shower that streamed from the groin of the dark and stony vault down the moist walls, as though it were along the bed of some grotto glowing with sinuous stalactites that I was following my parents," (ML)

"mais soit qu’un rayon eût brillé, soit que mon regard en bougeant eût promené à travers la verrière tour à tour éteinte et rallumée un mouvant et précieux incendie, l’instant d’après elle avait pris l’éclat changeant d’une traîne de paon, puis elle tremblait et ondulait en une pluie flamboyante et fantastique qui dégouttait du haut de la voûte sombre et rocheuse, le long des parois humides, comme si c’était dans la nef de quelque grotte irisée de sinueux stalactites que je suivais mes parents, "

Although I'm not fluent in French, to me, the French has no urination reference. It seems to me that it's saying that the sun's ray is like a brilliant fire that moves like a Peacock's tail, trembling and swaying, and raining down from the ceiling and walls. In a nutshell, anyway. But no urination similarity like the English translation. I think that's Moncrieff's poetic take on this.

Let me find the passage regarding the Abbots of Combray in French.

Great responses! This is very helpful to my understanding. That makes much more sense that it is the stones and not the bodies.

I have now passed the part where the Narrator has met his Uncle's "friend" and unwittingly shared the information with his own parents and thus ending the relationship with his uncle!

But that whole part is surrounded by the bit of his reasoning at why being indoors is a better situation for him sensing the outdoors than actually being outside and being overwhelmed by all of the senses!

This is where I would like to have that auxiliary book with all of the paintings so I could see the frescoes that he is describing and comparing the kitchen girl to.

I have now passed the part where the Narrator has met his Uncle's "friend" and unwittingly shared the information with his own parents and thus ending the relationship with his uncle!

But that whole part is surrounded by the bit of his reasoning at why being indoors is a better situation for him sensing the outdoors than actually being outside and being overwhelmed by all of the senses!

This is where I would like to have that auxiliary book with all of the paintings so I could see the frescoes that he is describing and comparing the kitchen girl to.

Daniel wrote: "I'm only halfway through this week's readings, but the discussion so far is helping me immensely. The sections about the church were also difficult for me.

It seems to me that these people are usi..."

I really appreciate these thoughts Daniel as I remember that part about the sun but another part of that encounter with M.Legrandin really stuck out for me and consumed more of my thoughts:

"On our way home from mass we would often meet M. Legrandin, who, detained in Paris by his professional duties as an engineer, could only (except in the regular holiday seasons) visit his house at Combray between Saturday evenings and Monday mornings. He was one of that class of men who, apart from a scientific career in which they may well have proved brilliantly successful, have acquired an entirely different kind of culture, literary or artistic, for which their professional specialization has no use but by which their conversation profits. More lettered than many men of letters (we were not aware at this period M. Legrandin had a distinct reputation as a writer, and were greatly astonished to find that a well-known composer had set some verses of his to music), endowed with greater "facility" than many painters, they imagine that the life they are obliged to lead is not that for which they are really fitted and they bring their regular occupations either an indifference tinged with fantasy, or a sustained and haughty application, scornful, bitter, and conscientious."

I think this could apply to anyone who has trained for and entered a certain field and yearns to be in another. Yet it turns out that I am an engineer who yearns to be a writer or to have a career otherwise in literature so it struck home with me.

It seems to me that these people are usi..."

I really appreciate these thoughts Daniel as I remember that part about the sun but another part of that encounter with M.Legrandin really stuck out for me and consumed more of my thoughts:

"On our way home from mass we would often meet M. Legrandin, who, detained in Paris by his professional duties as an engineer, could only (except in the regular holiday seasons) visit his house at Combray between Saturday evenings and Monday mornings. He was one of that class of men who, apart from a scientific career in which they may well have proved brilliantly successful, have acquired an entirely different kind of culture, literary or artistic, for which their professional specialization has no use but by which their conversation profits. More lettered than many men of letters (we were not aware at this period M. Legrandin had a distinct reputation as a writer, and were greatly astonished to find that a well-known composer had set some verses of his to music), endowed with greater "facility" than many painters, they imagine that the life they are obliged to lead is not that for which they are really fitted and they bring their regular occupations either an indifference tinged with fantasy, or a sustained and haughty application, scornful, bitter, and conscientious."

I think this could apply to anyone who has trained for and entered a certain field and yearns to be in another. Yet it turns out that I am an engineer who yearns to be a writer or to have a career otherwise in literature so it struck home with me.

Jeremy wrote: This is where I would like to have that auxiliary book with all of the paintings so I could see the frescoes that he is describing and comparing the kitchen girl to.

Jeremy wrote: This is where I would like to have that auxiliary book with all of the paintings so I could see the frescoes that he is describing and comparing the kitchen girl to. There's a picture of Giotto's Charity over at Book Drum: http://www.bookdrum.com/books/in-sear...

Larry wrote: "I’m new to Proust and very excited to be part of the group. I began Swann’s Way in December and by the beginning of the new year was several weeks ahead, so I decided to put it down for a bit and ..."

Larry wrote: "I’m new to Proust and very excited to be part of the group. I began Swann’s Way in December and by the beginning of the new year was several weeks ahead, so I decided to put it down for a bit and ..."Welcome, Larry. I'm glad you're enjoying it.

Jeremy, welcome!

Jeremy, welcome!Found another excellent source for Proust questions while trying to find out what a "bleu" was (the pink lady uses the term: “Couldn’t he come to me some day for ‘a cup of tea,’ as our friends across the Channel say? He need only send me a ‘blue’ in the morning?”. It's called Proust Ink and here's the page that explains "bleu": http://www.proust-ink.com/library/pro...

Jeremy wrote: "I am curious if anyone understood the meaning of this passage:

Jeremy wrote: "I am curious if anyone understood the meaning of this passage: "Its memorial stones, beneath which the noble dust of the Abbots of Combray who lay buried there furnished the choir with a sort of..."

Back at home now and I just checked the French, but Karen and Madame X above have already identified it is the stones that are turning to honey.

The French text:

Ses pierres tombales , sous lesquelles la noble poussière des abbés de Combray, enterrés là, faisait au chœur comme un pavage spirituel, n’étaient plus elles-mêmes de la matière dure, car le temps les avait rendus douces et fait couler comme du miel hors le limite du propre équarrissure qu’ici elles avaient dépassées d’un flot blond, entrainant à la dérive une majuscule gothique en fleurs, noyant les violettes blanches du marbre.

I'm glad to have you here, Valerie. I thought Proust is ideal for relaxation and de-stressing. I'm going back and forth between analytical books about Proust and the Proust. I need to mix it up often. Good luck on your dissertation.

I'm glad to have you here, Valerie. I thought Proust is ideal for relaxation and de-stressing. I'm going back and forth between analytical books about Proust and the Proust. I need to mix it up often. Good luck on your dissertation.

In an earlier post (and I think under the Karpeles thread) I put an illustration of a King from a stained glass with a Jesse Tree motif. Looking at pictures of the actual church at Illiers-Combray, I have found the ones Proust must have had in mind. They do look like playing cards, but they are not Kings, but Saints (when I read “kings” I had to think of the Jesse trees, because it is rare to find worldly figures in Medieval stained glass). These Illiers windows are not really medieval either, but of a later late, at least from the Renaissance, or in the style of the Renaissance.

In an earlier post (and I think under the Karpeles thread) I put an illustration of a King from a stained glass with a Jesse Tree motif. Looking at pictures of the actual church at Illiers-Combray, I have found the ones Proust must have had in mind. They do look like playing cards, but they are not Kings, but Saints (when I read “kings” I had to think of the Jesse trees, because it is rare to find worldly figures in Medieval stained glass). These Illiers windows are not really medieval either, but of a later late, at least from the Renaissance, or in the style of the Renaissance.

The one in the Middle is St-Jacques, or Santiago (San Jaime) with the accoutrements of a pilgrim (see image below). Illiers was on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela in North West Spain. Please note the yellow Shells that this Saint has on the upper part of his cape. These shells are the origin of the famous madeleines.

Aloha wrote: ""but, either because a ray of sunlight had gleamed through it or because my own shifting glance had sent shooting across the window, whose colours died away and were rekindled by turns, a rare and ..."

Aloha wrote: ""but, either because a ray of sunlight had gleamed through it or because my own shifting glance had sent shooting across the window, whose colours died away and were rekindled by turns, a rare and ..."This discussion of groin vaults and sunlight may be misleading if one does not realizes that groin vault is a technical term. It is interesting that Proust refers to the height of the vault but the English has the groin of the vault, playing with the technical term. It is too bad that this terminological confusion interferes with Proust's lovely description of the flowing light streaming through the church.

Here we are with the fragmentation of the self again, the passage on reading in the garden, there's a juxtaposition of different states of consciousness, moving from the inside to the outside, these concurrent states that are reminiscent of a dream, but a dream that we can remember, intense emotions, pure interior, then a slightly less interior imagining of the places he's reading about until finally he moves outwards to a consciousness of his physical state, where he's sitting and suddenly hearing the chimes of the clock ringing the hour, that he hadn't heard while he was so engrossed.

Here we are with the fragmentation of the self again, the passage on reading in the garden, there's a juxtaposition of different states of consciousness, moving from the inside to the outside, these concurrent states that are reminiscent of a dream, but a dream that we can remember, intense emotions, pure interior, then a slightly less interior imagining of the places he's reading about until finally he moves outwards to a consciousness of his physical state, where he's sitting and suddenly hearing the chimes of the clock ringing the hour, that he hadn't heard while he was so engrossed.There's that movement again too between different stages of life of The Narrator representing to us very directly the boy seeing the book in the other shop in Combray that Francoise doesn't go to, and recalling that it had been recommended to him, the boy lifting his eyes to the horizon as he reads, but then also the older narrator, the man of experience who knows that searching for these imaginary places in real life will only deal in disappointment, who is looking back from today over a whole life, and seeing how the heart has changed over the stretch of that life.

It's magnificent how he moves in and out, interior and exterior, and also backwards and forwards in time. There's an ease and a breadth to it that is breathtaking.

Karen wrote: "Here we are with the fragmentation of the self again, the passage on reading in the garden, there's a juxtaposition of different states of consciousness, moving from the inside to the outside, thes..."

Karen wrote: "Here we are with the fragmentation of the self again, the passage on reading in the garden, there's a juxtaposition of different states of consciousness, moving from the inside to the outside, thes..."I also liked that passage, and you bring out the aspects so very well...!!

Aloha Wrote: "...to me, his grammatical usage is designed to create a revolution around a particular point. Note how the qualifiers do their job to shift perspectives from the church of Combray."

Aloha Wrote: "...to me, his grammatical usage is designed to create a revolution around a particular point. Note how the qualifiers do their job to shift perspectives from the church of Combray."Aloha, Interesting, could you expand on what you say, thank you; are you speaking of that sentence or of successive ones about the church?

Jeremy wrote: "This is where I would like to have that auxiliary book with all of the paintings so I could see the frescoes that he is describing and comparing the kitchen girl to. "

Jeremy wrote: "This is where I would like to have that auxiliary book with all of the paintings so I could see the frescoes that he is describing and comparing the kitchen girl to. "Jeremy, this is where the Internet comes in very handy! Just do a google image search on "Giotto virtues and vices" and great pics will pop up. Here is the gallery I was using while reading but there are hundreds to choose from: http://www.flickr.com/photos/28433765...

I have to say that Proust is right, these Virtues appear pretty unidealized.

Looking at my search history, I also looked up "Bellini Mohammed II" last night to see what Bloch looked like (without the goatee, of course).

Nick wrote: "...I think you'd really enjoy Figures III. Genette on narrative theory, using Proust as his main source of examples.

Nick wrote: "...I think you'd really enjoy Figures III. Genette on narrative theory, using Proust as his main source of examples. Nick, you're my man; you recommended Bales, I bought it & found Malcolm Bowie's Proust & the Art of Brevity inside; you recommend Genette's Figures III & I just bought it used in NJ for $11.91, thanks.

Aloha wrote: "the steeple of Combray is the fixed point, while the Narrator sees the steeple from varying angles. This is the reverse of last week's Narrator as child in bed scene, where the bed is the fixed point while everything else revolves around it, with the Magic Lantern as a nice symbol for that. And then there's the apse again in relation to the steeple:"

Just wanted to chime in to say that I hadn't perceived this inversion so clearly when I read & it's a really brilliant comment.

Personally, I see the point of this as being something like porousness or interlacing. The way that the the stone is worn into fluid shapes by time or the colors of the stained glass windows bleed, also, is in a similar vein. Things aren't ever solid or isolated; they exist in context, spatial or metaphorical or personal or, obviously, temporal.

Sometimes we have to work to get the context, like the narrator moving all over the town and describing all the different views of the church - different from every spot, like those Monet paintings of hay that change with every hour of the day. But sometimes the things themselves provide the context, as the stones that melt and the windows that bleed.

Just wanted to chime in to say that I hadn't perceived this inversion so clearly when I read & it's a really brilliant comment.

Personally, I see the point of this as being something like porousness or interlacing. The way that the the stone is worn into fluid shapes by time or the colors of the stained glass windows bleed, also, is in a similar vein. Things aren't ever solid or isolated; they exist in context, spatial or metaphorical or personal or, obviously, temporal.

Sometimes we have to work to get the context, like the narrator moving all over the town and describing all the different views of the church - different from every spot, like those Monet paintings of hay that change with every hour of the day. But sometimes the things themselves provide the context, as the stones that melt and the windows that bleed.

"Combray, from a distance, for ten leagues around, seen from the railway when we arrived there the last week before Easter, was no more than a church summing up the town, representing it, speaking of it and for it into the distance, and, when one approached, holding close around its high dark cloak, in the middle of a field, against the wind, like a shepherdess her sheep, the woolly gray backs of the gathered houses, which a vestige of medieval ramparts girdled here and there with a line as perfectly circular as a small town in a primitive painting."

"Combray, from a distance, for ten leagues around, seen from the railway when we arrived there the last week before Easter, was no more than a church summing up the town, representing it, speaking of it and for it into the distance, and, when one approached, holding close around its high dark cloak, in the middle of a field, against the wind, like a shepherdess her sheep, the woolly gray backs of the gathered houses, which a vestige of medieval ramparts girdled here and there with a line as perfectly circular as a small town in a primitive painting."He starts with "Combray", to confirm it as the focal point.

from a distance - We are moved to "a distance" from Combray

seen from a railway - we are moved to looking at Combray from a railway

Then Combray breathes into the town:

summing up the town

representing it

speaking of it and for it

Then, the movement of "when one approached"

holding close around its high dark cloak, etc., etc....

with a line as perfectly circular...

He's looking at Combray from varying angles in much the same way as if he's looking at the church. Note how the "line as perfectly circular" can be the apse of the church.

This is also in response to Madame X's post. My hunch is that he's repeating the layout of the cathedral in his stories, the town of Combray, etc. I recall from art school that each part of the cathedral layout has a symbolic significance, as are the direction that the areas are pointing. I may be wrong, but I think he's pointing out special focal points according to how he weave words, the rotations, the equilibrium points. I'm making notes of the tension between areas according to how he words it, and how he weaves time. This is when I wish I was fluent in French. This is how he's building the layout of the metaphorical cathedral in this novel.

This is only a hunch, though. I've only read the first book. I hope this makes sense.

Just as this one, in the smoking room where my uncle was wearing his plain jacket to receive her, generously diffused her soft and sweet body, her dress of pink silk, her pearls, the elegance that emanates from the friendsip of a grand duke, so in the sme way she had taken some insignificant remark of my father's, had worked it delicately, turned it, given it a precious appellation, and enchasing it with one of her glances of the finest water, tinged with humility and gratitude, had given it back changed into an artistc jewel, into something "completely exquisite." (79-80) What a sentence.

Just as this one, in the smoking room where my uncle was wearing his plain jacket to receive her, generously diffused her soft and sweet body, her dress of pink silk, her pearls, the elegance that emanates from the friendsip of a grand duke, so in the sme way she had taken some insignificant remark of my father's, had worked it delicately, turned it, given it a precious appellation, and enchasing it with one of her glances of the finest water, tinged with humility and gratitude, had given it back changed into an artistc jewel, into something "completely exquisite." (79-80) What a sentence.This woman in the pink dress and pearls eating her tangerine and the way the narrator regards her makes me wonder why you all are going on and on about the church of Combray when this is where the narrator is at his finest. #just sayin ;)

Thanks, P. It'll be fun being detectives and catching all the beautiful subtleties. I think it helps "seeing" and feeling how the novel flows.

Thanks, P. It'll be fun being detectives and catching all the beautiful subtleties. I think it helps "seeing" and feeling how the novel flows.

Proustitute wrote: "ReemK, I think the emphasis on the church is important given Proust's remark that his novel was structured like a cathedral, notably after he had read Ruskin's work which gave him the key to how to..."

Proustitute wrote: "ReemK, I think the emphasis on the church is important given Proust's remark that his novel was structured like a cathedral, notably after he had read Ruskin's work which gave him the key to how to..."I'm just teasing. I have great admiration for beautiful architecture and have appreciated the discussion the group has been having. However, this woman as viewed by the narrator is quite intriguing!

"Crazed with love for the lady in pink"

Reem, we can chip in with what we each notice. It doesn't have to be limited to one aspect. Feel free to note what appeals to you.

Reem, we can chip in with what we each notice. It doesn't have to be limited to one aspect. Feel free to note what appeals to you.

Books mentioned in this topic

Proust in Love (other topics)Textual Awareness: A Genetic Study of Late Manuscripts by Joyce, Proust, and Mann (other topics)

Proust's Additions: The Making of 'A la recherche du temps perdu' (other topics)

The Lemoine Affair (other topics)

Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (other topics)

More...