The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Woodrow Wilson

PRESIDENTIAL SERIES

>

WOODROW WILSON: A BIOGRAPHY - GLOSSARY (SPOILER THREAD)

message 151:

by

Bryan

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

May 06, 2013 08:28AM

Indeed, Ann, many industries were owned by foreign companies in the area. It did great create great resentment and entrenched foreign interests.

Indeed, Ann, many industries were owned by foreign companies in the area. It did great create great resentment and entrenched foreign interests.

reply

|

flag

James Slayden:

James Slayden:

a Representative from Texas; born in Mayfield, Graves County, Ky., June 1, 1853; upon the death of his father in 1869 moved with his mother to New Orleans, La.; attended the common schools and Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Va.; moved to San Antonio, Tex., in 1876; became a cotton merchant and ranchman; member of the State house of representatives in 1892; declined to be a candidate for renomination; engaged in agricultural pursuits and mining; appointed by Andrew Carnegie as one of the original trustees of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in October 1910; president of the American Peace Society for several years; elected as a Democrat to the Fifty-fifth and to the ten succeeding Congresses (March 4, 1897-March 3, 1919); declined renomination in 1918; managed an orchard in Virginia, a ranch in Texas, and mines in Mexico; died in San Antonio, Tex., February 24, 1924; interment in Mission Park Cemetery.

(Source: http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/...)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_L...

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/on...

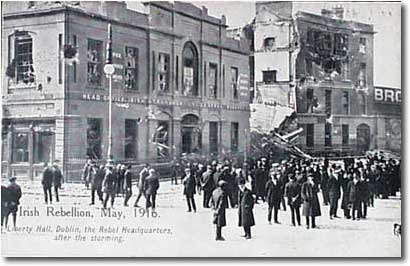

United States occupation of the Dominican Republic:

United States occupation of the Dominican Republic:

The assassination of Cáceres turned out to be but the first act of a frenzied drama that culminated in the republic's occupation by the United States. The fiscal stability that had resulted from the 1905 receivership eroded under Cáceres's successor, Eladio Victoria y Victoria; most of the increased outlays went to support military campaigns against rebellious partisans, mainly in the Cibao. The continued violence and instability prompted the administration of President William H. Taft to dispatch a commission to Santo Domingo on September 24, 1912, to mediate among the warring factions. The presence of a 750-member force of United States Marines apparently convinced the Dominicans of the seriousness of Washington's threats to intervene directly in the conflict; Victoria agreed to step down in favor of a neutral figure, Roman Catholic archbishop Adolfo Alejandro Nouel Bobadilla. The archbishop assumed office as provisional president on November 30.

Nouel proved unequal to the burden of national leadership. Unable to mediate successfully between the ambitions of rival horacistas and jimenistas, he stepped down on March 31, 1913. His successor, José Bordas Valdés, was equally unable to restrain the renewed outbreak of hostilities. Once again, Washington took a direct hand and mediated a resolution. The rebellious horacistas agreed to a cease-fire based on a pledge of United States oversight of elections for members of local ayuntamientos and a constituent assembly that would draft the procedures for presidential balloting. The process, however, was flagrantly manipulated and resulted in Bordas's reelection on June 15, 1914. Both horacistas and jimenistas took offense at this blatant maneuver and rose up against Bordas.

The United States government, this time under President Woodrow Wilson, again intervened. Where Taft had cajoled the combatants with a clear intimation of military action, Wilson delivered an ultimatum: elect a president or the United States will impose one. The Dominicans accordingly selected Ramón Báez Machado as provisional president on August 27, 1914. Comparatively fair presidential elections held on October 25 returned Jiménez to the presidency. Despite his victory, however, Jiménez felt impelled to appoint leaders and prominent members of the various political factions to positions in his government in an effort to broaden its support. The internecine conflicts that resulted had quite the opposite effect, weakening the government and the president and emboldening Secretary of War Desiderio Arias to take control of both the armed forces and the Congress, which he compelled to impeach Jiménez for violation of the constitution and the laws. Although the United States ambassador offered military support to his government, Jiménez opted to step down on May 7, 1916.

Arias never formally assumed the presidency. The United States government had apparently tired of its recurring role as mediator and had decided to take more direct action. United States forces had already occupied Haiti by this time. The initial military administrator of Haiti, Rear Admiral William Caperton, had actually forced Arias to retreat from Santo Domingo by threatening the city with naval bombardment on May 13. The first Marines landed three days later. Although they established effective control of the country within two months, the United States forces did not proclaim a military government until November. Most Dominican laws and institutions remained intact under military rule, although the shortage of Dominicans willing to serve in the cabinet forced the military governor, Rear Admiral Harry S. Knapp, to fill a number of portfolios with United States naval officers. The press and radio were censored for most of the occupation, and public speech was limited.

The surface effects of the occupation were largely positive. The Marines restored order throughout most of the republic (with the exception of the eastern region); the country's budget was balanced, its debt was diminished, and economic growth resumed; infrastructure projects produced new roads that linked all the country's regions for the first time in its history; a professional military organization, the Dominican Constabulary Guard, replaced the partisan forces that had waged a seemingly endless struggle for power. Most Dominicans, however, greatly resented the loss of their sovereignty to foreigners, few of whom spoke Spanish or displayed much real concern for the welfare of the republic.

The most intense opposition to the occupation arose in the eastern provinces of El Seibo and San Pedro de Macorís. From 1917 to 1921, the United States forces battled a guerrilla movement in that area known as the gavilleros. The guerrillas enjoyed considerable support among the population, and they benefited from a superior knowledge of the terrain. The movement survived the capture and the execution of its leader, Vicente Evangelista, and some initially fierce encounters with the Marines. However, the gavilleros eventually yielded to the occupying forces' superior firepower, air power (a squadron of six Curtis Jennies), and determined (often brutal) counterinsurgent methods.

After World War I, public opinion in the United States began to run against the occupation. Warren G. Harding, who succeeded Wilson in March 1921, had campaigned against the occupations of both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In June 1921, United States representatives presented a withdrawal proposal, known as the Harding Plan, which called for Dominican ratification of all acts of the military government, approval of a loan of US$2.5 million for public works and other expenses, the acceptance of United States officers for the constabulary--now known as the National Guard (Guardia Nacional)--and the holding of elections under United States supervision. Popular reaction to the plan was overwhelmingly negative. Moderate Dominican leaders, however, used the plan as the basis for further negotiations that resulted in an agreement allowing for the selection of a provisional president to rule until elections could be organized. Under the supervision of High Commissioner Sumner Welles, Juan Bautista Vicini Burgos assumed the provisional presidency on October 21, 1922. In the presidential election of March 15, 1924, Horacio Vásquez Lajara handily defeated Francisco J. Peynado. Vásquez's Alliance Party (Partido Alianza) also won a comfortable majority in both houses of Congress. With his inauguration on July 13, control of the republic returned to Dominican hands.

(Source: http://www.onwar.com/aced/nation/day/...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1916_Uni...

United States occupation of Haiti (1915):

United States occupation of Haiti (1915):[image error]

Increased instability in Haiti in the years before 1915 led to heightened action by the United States to deter foreign influence. Between 1911 and 1915, seven presidents were assassinated or overthrown in Haiti, increasing U.S. policymakers’ fear of foreign intervention. In 1914, the Wilson Administration sent marines into Haiti who removed $500,000 from the Haitian National Bank in December of 1914 for safe-keeping in New York, thus giving the U.S. control of the bank. In 1915, Haitian president Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam was assassinated and the situation in Haiti quickly became unstable. In response, President Wilson sent the U.S. Marines to Haiti, claiming the invasion was an attempt to prevent anarchy. In reality the Wilson administration was protecting U.S. assets in the area and preventing a possible German invasion.

The invasion ended with the Haitian-American Treaty of 1915. The articles of this agreement created a Haitian gendarmerie, essentially a military force made up of Americans and Haitians and controlled by the U.S. marines. The United States gained complete control over Haitian finances, and the right to intervene in Haiti whenever the U.S. Government deemed necessary. The U.S. Government also forced the election of a new pro-American President, Philippe Sudré Dartiguenave, by the Haitian legislature in August of 1915. The selection of a President that did not represent the choice of the Haitian populace increased unrest in Haiti.

Following the successful manipulation of the 1915 elections, the Wilson Administration attempted to strong-arm the Haitian legislature into adopting a new constitution in 1917. This constitution allowed foreign land ownership, which had been outlawed since the Haitian Revolution as a way to prevent foreign control of the country. The legislature was extremely reluctant to change the long-standing law and rejected the new constitution. Law-makers began drafting a new anti-American constitution, but the United States forced President Dartiguenave dissolve the legislature, which did not meet again until 1929.

(Source: http://history.state.gov/milestones/1...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_S...

Mary A. Renda

Mary A. Renda Hans Schmidt

Hans Schmidt

Jones Act (Philippines):

Jones Act (Philippines):was an Organic Act passed by the United States Congress. The law replaced the Philippine Organic Act of 1902 and acted like a constitution of the Philippines from its enactment until 1934 when the Tydings–McDuffie Act was passed (which in turn led eventually to the Commonwealth of the Philippines and to independence from the United States). The Jones Law created the first fully elected Philippine legislature.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jones_La...)

More:

http://countrystudies.us/philippines/...

http://www.gov.ph/the-philippine-cons...

Paul A. Kramer

Paul A. Kramer

Bright's Disease:

Bright's Disease:is a historical classification of kidney diseases that would be described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. The term is no longer used, as diseases are now classified according to their more fully understood causes.

It is typically denoted by the presence of serum albumin (blood plasma protein) in the urine, and frequently accompanied by edema and hypertension.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bright%2...)

Herbert Hoover:

Herbert Hoover:

Herbert Clark Hoover was born on August 10, 1874. For the first nine years of his life, he lived in the small town of West Branch, Iowa, the place of his birth. His Quaker father, Jessie Clark Hoover, a blacksmith and farm equipment salesman, suffered a heart attack and died when Herbert was six years old. Three years later, the boy's mother, Huldah Minthorn Hoover, developed pneumonia and also passed away, orphaning Herbert, his older brother Theodore, and little sister Mary. Passed around among relatives for a few years, Hoover ended up with his uncle, Dr. John Minthorn, who lived in Oregon.

The young Hoover was shy, sensitive, introverted, and somewhat suspicious, characteristics that developed, at least in part, in reaction to the loss of his parents at such a young age. He attended Friends Pacific Academy in Newberg, Oregon, earning average to failing grades in all subjects except math. Determined, nevertheless, to go to the newly established Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, Hoover studied hard and barely passed the university's entrance exam. He went on to major in geology and participated in a host of extracurricular activities, serving as class treasurer of the junior and senior student bodies and managing the school baseball and football teams. To pay his tuition, Hoover worked as a clerk in the registration office and showed considerable entrepreneurial skill by starting a student laundry service.

Career and Monetary Success

During the summers, Hoover worked as a student assistant on geological survey teams in Arkansas, California, and Nevada. After his graduation in 1895, he looked hard to find work as a surveyor but ended up laboring seventy hours a week at a gold mine near Nevada City, California, pushing ore carts. Luck came his way with an office job in San Francisco, putting him in touch with a firm in need of an engineer to inspect and evaluate mines for potential purchase. Hoover then moved to Australia in 1897 and China in 1899, where he worked as a mining engineer until 1902. A string of similar jobs took him all over the world and helped Hoover become a giant in his field. He opened his own mining consulting business in 1908; by 1914, Hoover was financially secure, earning his wealth from high-salaried positions, his ownership of profitable Burmese silver mines, and royalties from writing the leading textbook on mining engineering.

His wife, Lou Henry Hoover, traveled with him everywhere he went. Herbert and Lou met in college, where she was the sole female geology major at Stanford. He proposed to her by cable from Australia as he prepared to move to China; she accepted by return wire and they married in 1899. The couple was in China during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, a time when Lou helped nurse wounded Western diplomats and soldiers while Herbert assisted in the fighting to defend Tianjin, a city near the uprising. By the time the couple returned home to America in 1917, Lou had learned to shoot a gun and had mastered eight languages.

Humanitarian Efficiency

Over the course of his career as a mining engineer and businessman, Hoover's intellect and understanding of the world matured considerably. Hoover was raised a Quaker and although he rarely went to Meeting as an adult, he internalized that faith's belief in the power of the individual, the importance of freedom, and the value of "conscientious work" and charity. Hoover also applied the ethos of engineering to the world in general, believing that scientific expertise, when employed thoughtfully and properly, led to human progress. Hoover worked comfortably in a capitalist economy but believed in labor's right to organize and hoped that cooperation (between labor and management and among competitors) might come to characterize economic relations. During these years, Hoover repeatedly made known to friends his desire for public service.

Politically, Hoover identified with the progressive wing of the Republican Party, supporting Theodore Roosevelt's third-party bid in 1912. World War I brought Hoover to prominence in American politics and thrust him into the international spotlight. In London when the war broke out, he was asked by the U.S. consul to organize the evacuation of 120,000 Americans trapped in Europe. Germany's devastating invasion of Belgium led Hoover to pool his money with several wealthy friends to organize the Committee for the Relief of Belgium. Working without direct government support, Hoover raised millions of dollars for food and medicine to help desperate Belgians.

In 1917, after the United States entered the war, President Woodrow Wilson asked Hoover to run the U.S. Food Administration. Hoover performed quite admirably, guiding the effort to conserve resources and supplies needed for the war and to feed America's European allies. Hoover even became a household name during the war; nearly all Americans knew that the verb "to Hooverize" meant the rationing of household materials. After the armistice treaty was signed in November 1918, officially ending World War I, Wilson appointed Hoover to head the European Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. In this capacity, Hoover channeled 34 million tons of American food, clothing, and supplies to war-torn Europe, aiding people in twenty nations.

His service during World War I made Hoover one of the few Republicans trusted by Wilson. Because of Hoover's knowledge of world affairs, Wilson relied him at the Versailles Peace Conference and as director of the President's Supreme Economic Council in 1918. The following year, Hoover founded the Hoover Library on War, Revolution, and Peace at Stanford University as an archive for the records of World War I. This privately endowed organization later became the Hoover Institution, devoted to the study of peace and war. No isolationist, Hoover supported American participation in the League of Nations. He believed, though, that Wilson's stubborn idealism led Congress to reject American participation in the League.

(Source: http://millercenter.org/president/hoo...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_...

http://www.whitehouse.gov/about/presi...

George H. Nash

George H. Nash

Cecil Spring-Rice:

Cecil Spring-Rice:

Cecil Arthur Spring-Rice was born 27 February 1859, son of Charles and Elizabeth Spring-Rice. He was educated at Eton College then Balliol College, Oxford. In 1904 he married Florence Lascelles (daughter of Sir Frank Lascelles), with whom he had one son and one daughter.

In 1882 he entered the Foreign Office and was Assistant Private Secretary to Lord Granville and précis writer for Lord Rosebery. He held a series of diplomatic posts including: Secretary of Legation in Brussels, Washington, Tokyo, Berlin and Constantinople [Istanbul]; Charge d'Affaires Tehran (1900); British Commissioner of the Public Debt in Cairo (1901); 1st Secretary St Petersburg (1903); Minister and Consul General Persia [Iran](1906); Minister in Sweden (1908-1913); and British Ambassador in Washington (1912-1917). Spring-Rice was also a poet and the author of "I vow to thee my country", the famous hymn. He died on 14 February 1918.

(Source: http://janus.lib.cam.ac.uk/db/node.xs...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecil_Sp...

David Henry Burton

David Henry Burton

Sir Edward Grey:

Sir Edward Grey:

Edward Grey, the son of Lieutenant-Colonel George Henry Grey, and grand-nephew of Earl Grey, was born in 1862. Educated at Winchester and Balliol College, Oxford, he was a strong supporter of the Liberal Party.

In the 1885 General Election Grey was elected to represent Bereick-on-Tweed. Following the 1892 General Election William Gladstone appointed Grey as Secretary for Foreign Affairs.

After the defeat of the Liberal Party in the 1895 General Election, Grey sat on the opposition benches until recalled to the post as Secretary of Foreign Affairs in the government formed by Henry Cambell-Bannerman in 1905.

Grey became concerned by the arms spending of Germany. In 1906 he argued: "The economic rivalry and all that do not give much offence to our people, and they admire (Germany's) steady industry and genius for organization. But they do resent mischief making. They suspect the Emperor of aggressive plans of Weltpolitik, and they see that Germany is forcing the pace in armaments in order to dominate Europe and is thereby laying a horrible burden of wasteful expenditure upon all the other powers."

Kaiser Wilhelm II gave an interview to the Daily Telegraph in October 1908: "Germany is a young and growing empire. She has a world-wide commerce which is rapidly expanding and to which the legitimate ambition of patriotic Germans refuses to assign any bounds. Germany must have a powerful fleet to protect that commerce and her manifold interests in even the most distant seas. She expects those interests to go on growing, and she must be able to champion them manfully in any quarter of the globe. Her horizons stretch far away. She must be prepared for any eventualities in the Far East. Who can foresee what may take place in the Pacific in the days to come, days not so distant as some believe, but days at any rate, for which all European powers with Far Eastern interests ought steadily to prepare?"

Grey replied to these comments in the same newspaper: "The German Emperor is ageing me; he is like a battleship with steam up and screws going, but with no rudder, and he will run into something some day and cause a catastrophe. He has the strongest army in the world and the Germans don't like being laughed at and are looking for somebody on whom to vent their temper and use their strength. After a big war a nation doesn't want another for a generation or more. Now it is 38 years since Germany had her last war, and she is very strong and very restless, like a person whose boots are too small for him. I don't think there will be war at present, but it will be difficult to keep the peace of Europe for another five years."

Grey made the defence of France against Germany aggression the central feature of British foreign policy through a number of private pledges but reduced their deterrent value by not making them public at the time. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28th July, 1914, brought the crisis to a head. The following month George Buchanan, the British ambassador to Russia, wrote to Grey about the discussions he had following the assassination: "As they both continued to press me to declare our complete solidarity with them, I said that I thought you might be prepared to represent strongly at Vienna and Berlin danger to European peace of an Austrian attack on Serbia. You might perhaps point out that it would in all probability force Russia to intervene, that this would bring Germany and France into the field, and that if war became general, it would be difficult for England to remain neutral. Minister for Foreign Affairs said that he hoped that we would in any case express strong reprobation of Austria's action. If war did break out, we would sooner or later be dragged into it, but if we did not make common cause with France and Russia from the outset we should have rendered war more likely."

Grey replied to Buchanan on the 25th July: "I said to the German Ambassador that, as long as there was only a dispute between Austria and Serbia alone, I did not feel entitled to intervene; but that, directly it was a matter between Austria and Russia, it became a question of the peace of Europe, which concerned us all. I had furthermore spoken on the assumption that Russia would mobilize, whereas the assumption of the German Government had hitherto been, officially, that Serbia would receive no support; and what I had said must influence the German Government to take the matter seriously. In effect, I was asking that if Russia mobilized against Austria, the German Government, who had been supporting the Austrian demand on Serbia, should ask Austria to consider some modification of her demands, under the threat of Russian mobilization."

Grey wrote to on Theobold von Bethmann Hollweg on 30th July, 1914: "His Majesty's Government cannot for one moment entertain the Chancellor's proposal that they should bind themselves to neutrality on such terms. What he asks us in effect is to engage and stand by while French colonies are taken and France is beaten, so long as Germany does not take French territory as distinct from the colonies. From the material point of view the proposal is unacceptable, for France, without further territory in Europe being taken from her, could be so crushed as to lose her position as a Great Power, and become subordinate to German policy. Altogether apart from that, it would be a disgrace to us to make this bargain with Germany at the expense of France, a disgrace from which the good name of this country would never recover. The Chancellor also in effect asks us to bargain away whatever obligation or interest we have as regards the neutrality of Belgium. We could not entertain that bargain either."

Grey later wrote in his autobiography, Twenty-five Years (1925) "That, if war came, the interest of Britain required that we should not stand aside, while France fought alone in the West, but must support her. I knew it to be very doubtful whether the Cabinet, Parliament, and the country would take this view on the outbreak of war, and through the whole of this week I had in view the probable contingency that we should not decide at the critical moment to support France. In that event I should have to resign; but the decision of the country could not be forced, and the contingency might not arise, and meanwhile I must go on."

Raymond Gram Swing, a journalist working for the Chicago Daily News, was asked by Theobold von Bethmann Hollweg to go to London to pass a message to Sir Edward Grey, the British foreign secretary. Bethmann-Hollweg warned him: "I must caution you... not a word of this in the newspapers. If it is published, I shall have to say I never said it." Swing wrote about his meeting in his autobiography, Good Evening (1964): "I had little firsthand knowledge of the British at that time. I knew how the Germans regarded them, Sir Edward Grey in particular. He was considered the arch-conspirator, the passionless builder of Germany's ring of enemies, and especially dangerous because of his ability to speak hypocritically about moral virtues - while acting in farsighted national interest. The Sir Edward Grey I met was a revelation. He had the personal appearance of a shaggy ascetic. He was tall, erect, slender, with thin but untidy hair. His clothes were not well pressed. At the time, I knew nothing about Sir Edward Grey, the naturalist, of the breed of Englishmen he represented -sensitive, shy, and complex - or that he was one of the best-educated men in the world. I delivered my message from Herr von Bethmann-Hollweg and ended with the instructions I had received to return to him and repeat what Sir Edward had to say in reply. Sir Edward's face turned crimson when I spoke the word "indemnity." I thought of Baroness von Schroeder's explanation of it and almost blurted it out. But Sir Edward gave me no time to blurt out anything. He ignored what I said about no annexations in Belgium and Belgian independence. He struck at the word "indemnity" with a kind of high moral fury, and launched into one of the finest speeches I had heard. Did not Herr von Bethmann-Holhweg know what must come from the war? It must be a world of international law where treaties were observed, where men welcomed conferences and did not scheme for war. I was to tell Herr von Bethmann-Holhveg that his suggestion of an indemnity was an insult and that Great Britain was fighting for a new basis for foreign relations, a new international morality."

On the outbreak of the First World War Grey believed that he had no alternative but to fulfill Britain's "obligations to honour" by joining France in its war with Germany. Grey's secret diplomacy was strongly criticised by the Labour Party and some members of his own party, including Charles Trevelyan, Secretary of the Board of Education, for these private promises made to the French government. Trevelyan resigned from the government over this issue and joined with E.D. Morel, George Cadbury, Ramsay MacDonald, Arthur Ponsonby, Arnold Rowntree and other critics of the Grey's foreign policy to form the Union of Democratic Control (UDC).

Grey was also deeply shocked by how his policies had failed to prevent war and prophesied that: "The lamps are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them in our lifetime." Grey's Balkan diplomacy was blamed for turning Turkey and Bulgaria against Britain and was excluded by Herbert Asquith from his Inner war cabinet.

Grey, the longest serving Secretary of Foreign Affairs in British history, was removed from office by David Lloyd George in December, 1916. He was granted the title Viscount Grey of Fallodon and became leader of the House of Lords. In retirement, Grey wrote his autobiography, Twenty Five Years (1925) and the best-selling, The Charm of Birds (1927).

Sir Edward Grey died 7th September 1933.

(Source: http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_G...

http://www.firstworldwar.com/bio/grey...

(no image)Twenty-Five Years, 1892-1916 by

Edward Grey

Edward Grey

Wilson's Second State of the Union, Part One:

Wilson's Second State of the Union, Part One:The session upon which you are now entering will be the closing session of the Sixty-third Congress, a Congress, I venture to say, which will long be remembered for the great body of thoughtful and constructive work which it has done, in loyal response to the thought and needs of the country. I should like in this address to review the notable record and try to make adequate assessment of it; but no doubt we stand too near the work that has been done and are ourselves too much part of it to play the part of historians toward it.

Our program of legislation with regard to the regulation of business is now virtually complete. It has been put forth, as we intended, as a whole, and leaves no conjecture as to what is to follow. The road at last lies clear and firm before business. It is a road which it can travel without fear or embarrassment. It is the road to ungrudged, unclouded success. In it every honest man, every man who believes that the public interest is part of his own interest, may walk with perfect confidence.

Moreover, our thoughts are now more of the future than of the past. While we have worked at our tasks of peace the circumstances of the whole age have been altered by war. What we have done for our own land and our own people we did with the best that was in us, whether of character or of intelligence, with sober enthusiasm and a confidence in the principles upon which we were acting which sustained us at every step of the difficult undertaking; but it is done. It has passed from our hands. It is now an established part of the legislation of the country. Its usefulness, its effects will disclose themselves in experience. What chiefly strikes us now, as we look about us during these closing days of a year which will be forever memorable in the history of the world, is that we face new tasks, have been facing them these six months, must face them in the months to come,-face them without partisan feeling, like men who have forgotten everything but a common duty and the fact that we are representatives of a great people whose thought is not of us but of what America owes to herself and to all mankind in such circumstances as these upon which we look amazed and anxious.

War has interrupted the means of trade not only but also the processes of production. In Europe it is destroying men and resources wholesale and upon a scale unprecedented and appalling, There is reason to fear that the time is near, if it be not already at hand, when several of the countries of Europe will find it difficult to do for their people what they have hitherto been always easily able to do,--many essential and fundamental things. At any rate, they will need our help and our manifold services as they have never needed them before; and we should be ready, more fit and ready than we have ever been.

It is of equal consequence that the nations whom Europe has usually supplied with innumerable articles of manufacture and commerce of which they are in constant need and without which their economic development halts and stands still can now get only a small part of what they formerly imported and eagerly look to us to supply their all but empty markets. This is particularly true of our own neighbors, the States, great and small, of Central and South America. Their lines of trade have hitherto run chiefly athwart the seas, not to our ports but to the ports of Great Britain and of the older continent of Europe. I do not stop to inquire why, or to make any comment on probable causes. What interests us just now is not the explanation but the fact, and our duty and opportunity in the presence of it. Here are markets which we must supply, and we must find the means of action. The United States, this great people for whom we speak and act, should be ready, as never before, to serve itself and to serve mankind; ready with its resources, its energies, its forces of production, and its means of distribution.

It is a very practical matter, a matter of ways and means. We have the resources, but are we fully ready to use them? And, if we can make ready what we have, have we the means at hand to distribute it? We are not fully ready; neither have we the means of distribution. We are willing, but we are not fully able. We have the wish to serve and to serve greatly, generously; but we are not prepared as we should be. We are not ready to mobilize our resources at once. We are not prepared to use them immediately and at their best, without delay and without waste.

To speak plainly, we have grossly erred in the way in which we have stunted and hindered the development of our merchant marine. And now, when we need ships, we have not got them. We have year after year debated, without end or conclusion, the best policy to pursue with regard to the use of the ores and forests and water powers of our national domain in the rich States of the West, when we should have acted; and they are still locked up. The key is still turned upon them, the door shut fast at which thousands of vigorous men, full of initiative, knock clamorously for admittance. The water power of our navigable streams outside the national domain also, even in the eastern States, where we have worked and planned for generations, is still not used as it might be, because we will and we won't; because the laws we have made do not intelligently balance encouragement against restraint. We withhold by regulation.

I have come to ask you to remedy and correct these mistakes and omissions, even at this short session of a Congress which would certainly seem to have done all the work that could reasonably be expected of it. The time and the circumstances are extraordinary, and so must our efforts be also.

Fortunately, two great measures, finely conceived, the one to unlock, with proper safeguards, the resources of the national domain, the other to encourage the use of the navigable waters outside that domain for the generation of power, have already passed the House of Representatives and are ready for immediate consideration and action by the Senate. With the deepest earnestness I urge their prompt passage. In them both we turn our backs upon hesitation and makeshift and formulate a genuine policy of use and conservation, in the best sense of those words. We owe the one measure not only to the people of that great western country for whose free and systematic development, as it seems to me, our legislation has done so little, but also to the people of the Nation as a whole; and we as clearly owe the other fulfillment of our repeated promises that the water power of the country should in fact as well as in name be put at the disposal of great industries which can make economical and profitable use of it, the rights of the public being adequately guarded the while, and monopoly in the use prevented. To have begun such measures and not completed them would indeed mar the record of this great Congress very seriously. I hope and confidently believe that they will be completed.

And there is another great piece of legislation which awaits and should receive the sanction of the Senate: I mean the bill which gives a larger measure of self-government to the people of the Philippines. How better, in this time of anxious questioning and perplexed policy, could we show our confidence in the principles of liberty, as the source as well as the expression of life, how better could we demonstrate our own self-possession and steadfastness in the courses of justice and disinterestedness than by thus going calmly forward to fulfill our promises to a dependent people, who will now look more anxiously than ever to see whether we have indeed the liberality, the unselfishness, the courage, the faith we have boasted and professed. I can not believe that the Senate will let this great measure of constructive justice await the action of another Congress. Its passage would nobly crown the record of these two years of memorable labor.

But I think that you will agree with me that this does not complete the toll of our duty. How are we to carry our goods to the empty markets of which I have spoken if we have not the ships? How are we to build tip a great trade if we have not the certain and con,;tpnt means of transportation upon which all profitable and useful commerce depends? And how are we to get the ships if we wait for the trade to develop without them? To correct the many mistakes by which we have discouraged and all but destroyed the merchant marine of the country, to retrace the steps by which we have.. it seems almost deliberately, withdrawn our flag from the seas.. except where, here and there, a ship of war is bidden carry it or some wandering yacht displays it, would take a long time and involve many detailed items of legislation, and tile trade which we ought immediately to handle would disappear or find other channels while we debated the items.

The case is not unlike that which confronted us when our own continent was to be opened up to settlement and industry, and we needed long lines of railway, extended means of transportation prepared beforehand, if development was not to lag intolerably and wait interminably. We lavishly subsidized the building of transcontinental railroads. We look back upon that with regret now, because the subsidies led to many scandals of which we are ashamed; but we know that the railroads had to be built, and if we had it to do over again we should of course build them, but in another way. Therefore I propose another way of providing the means of transportation, which must precede, not tardily follow, the development of our trade with our neighbor states of America. It may seem a reversal of the natural order of things, but it is true, that the routes of trade must be actually opened-by many ships and regular sailings and moderate charges-before streams of merchandise will flow freely and profitably through them.

Hence the pending shipping bill, discussed at the last session but as yet passed by neither House. In my judgment such legislation is imperatively needed and can not wisely be postponed. The Government must open these gates of trade, and open them wide; open them before it is altogether profitable to open them, or altogether reasonable to ask private capital to open them at a venture. It is not a question of the Government monopolizing the field. It should take action to make it certain that transportation at reasonable rates will be promptly provided, even where the carriage is not at first profitable; and then, when the carriage has become sufficiently profitable to attract and engage private capital, and engage it in abundance, the Government ought to withdraw. I very earnestly hope that the Congress will be of this opinion, and that both Houses will adopt this exceedingly important bill.

(Source: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/ind...)

Wilson's Second State of the Union, Part Two:

Wilson's Second State of the Union, Part Two:The great subject of rural credits still remains to be dealt with, and it is a matter of deep regret that the difficulties of the subject have seemed to render it impossible to complete a bill for passage at this session. But it can not be perfected yet, and therefore there are no other constructive measures the necessity for which I will at this time call your attention to; but I would be negligent of a very manifest duty were I not to call the attention of the Senate to the fact that the proposed convention for safety at sea awaits its confirmation and that the limit fixed in the convention itself for its acceptance is the last day of the present month. The conference in which this convention originated was called by the United States; the representatives of the United States played a very influential part indeed in framing the provisions of the proposed convention; and those provisions are in themselves for the most part admirable. It would hardly be consistent with the part we have played in the whole matter to let it drop and go by the board as if forgotten and neglected. It was ratified in May by the German Government and in August by the Parliament of Great Britain. It marks a most hopeful and decided advance in international civilization. We should show our earnest good faith in a great matter by adding our own acceptance of it.

There is another matter of which I must make special mention, if I am to discharge my conscience, lest it should escape your attention. It may seem a very small thing. It affects only a single item of appropriation. But many human lives and many great enterprises hang upon it. It is the matter of making adequate provision for the survey and charting of our coasts. It is immediately pressing and exigent in connection with the immense coast line of Alaska, a coast line greater than that of the United States themselves, though it is also very important indeed with regard to the older coasts of the continent. We can not use our great Alaskan domain, ships will not ply thither, if those coasts and their many hidden dangers are not thoroughly surveyed and charted. The work is incomplete at almost every point. Ships and lives have been lost in threading what were supposed to be well-known main channels. We have not provided adequate vessels or adequate machinery for the survey and charting. We have used old vessels that were not big enough or strong enough and which were so nearly unseaworthy that our inspectors would not have allowed private owners to send them to sea. This is a matter which, as I have said, seems small, but is in reality very great. Its importance has only to be looked into to be appreciated.

Before I close may I say a few words upon two topics, much discussed out of doors, upon which it is highly important that our judgment should be clear, definite, and steadfast?

One of these is economy in government expenditures. The duty of economy is not debatable. It is manifest and imperative. In the appropriations we pass we are spending the money of the great people whose servants we are,-not our own. We are trustees and responsible stewards in the spending. The only thing debatable and upon which we should be careful to make our thought and purpose clear is the kind of economy demanded of us. I assert with the greatest confidence that the people of the United States are not jealous of the amount their Government costs if they are sure that they get what they need and desire for the outlay, that the money is being spent for objects of which they approve, and that it is being applied with good business sense and management.

Governments grow, piecemeal, both in their tasks and in the means by which those tasks are to be performed, and very few Governments are organized, I venture to say, as wise and experienced business men would organize them if they had a clean sheet of paper to write upon. Certainly the Government of the United States is not. I think that it is generally agreed that there should be a systematic reorganization and reassembling of its parts so as to secure greater efficiency and effect considerable savings in expense. But the amount of money saved in that way would, I believe, though no doubt considerable in itself, running, it may be, into the millions, be relatively small,-small, I mean, in proportion to the total necessary outlays of the Government. It would be thoroughly worth effecting, as every saving would, great or small. Our duty is not altered by the scale of the saving. But my point is that the people of the United States do not wish to curtail the activities of this Government; they wish, rather, to enlarge them; and with every enlargement, with the mere growth, indeed, of the country itself, there must come, of course, the inevitable increase of expense. The sort of economy we ought to practice may be effected, and ought to be effected, by a careful study and assessment of the tasks to be performed; and the money spent ought to be made to yield the best possible returns in efficiency and achievement. And, like good stewards, we should so account for every dollar of our appropriations as to make it perfectly evident what it was spent for and in what way it was spent.

It is not expenditure but extravagance that we should fear being criticized for; not paying for the legitimate enterprise and undertakings of a great Government whose people command what it should do, but adding what will benefit only a few or pouring money out for what need not have been undertaken at all or might have been postponed or better and more economically conceived and carried out. The Nation is not niggardly; it is very generous. It will chide us only if we forget for whom we pay money out and whose money it is we pay. These are large and general standards, but they are not very difficult of application to particular cases.

The other topic I shall take leave to mention goes deeper into the principles of our national life and policy. It is the subject of national defense.

It can not be discussed without first answering some very searching questions. It is said in some quarters that we are not prepared for war. What is meant by being prepared? Is it meant that we are not ready upon brief notice to put a nation in the field, a nation of men trained to arms? Of course we are not ready to do that; and we shall never be in time of peace so long as we retain our present political principles and institutions. And what is it that it is suggested we should be prepared to do? To defend ourselves against attack? We have always found means to do that, and shall find them whenever it is necessary without calling our people away from their necessary tasks to render compulsory military service in times of peace.

Allow me to speak with great plainness and directness upon this great matter and to avow my convictions with deep earnestness. I have tried to know what America is, what her people think, what they are, what they most cherish and hold dear. I hope that some of their finer passions are in my own heart, --some of the great conceptions and desires which gave birth to this Government and which have made the voice of this people a voice of peace and hope and liberty among the peoples of the world, and that, speaking my own thoughts, I shall, at least in part, speak theirs also, however faintly and inadequately, upon this vital matter.

We are at peace with all the world. No one who speaks counsel based on fact or drawn from a just and candid interpretation of realities can say that there is reason to fear that from any quarter our independence or the integrity of our territory is threatened. Dread of the power of any other nation we are incapable of. We are not jealous of rivalry in the fields of commerce or of any other peaceful achievement. We mean to live our own lives as we will; but we mean also to let live. We are, indeed, a true friend to all the nations of the world, because we threaten none, covet the possessions of none, desire the overthrow of none. Our friendship can be accepted and is accepted without reservation, because it is offered in a spirit and for a purpose which no one need ever question or suspect. Therein lies our greatness. We are the champions of peace and of concord. And we should be very jealous of this distinction which we have sought to earn. just now we should be particularly jealous of it because it is our dearest present hope that this character and reputation may presently, in God's providence, bring us an opportunity such as has seldom been vouchsafed any nation, the opportunity to counsel and obtain peace in the world and reconciliation and a healing settlement of many a matter that has cooled and interrupted the friendship of nations. This is the time above all others when we should wish and resolve to keep our strength by self-possession, our influence by preserving our ancient principles of action.

From the first we have had a clear and settled policy with regard to military establishments. We never have had, and while we retain our present principles and ideals we never shall have, a large standing army. If asked, Are you ready to defend yourselves? we reply, Most assuredly, to the utmost; and yet we shall not turn America into a military camp. We will not ask our young men to spend the best years of their lives making soldiers of themselves. There is another sort of energy in us. It will know how to declare itself and make itself effective should occasion arise. And especially when half the world is on fire we shall be careful to make our moral insurance against the spread of the conflagration very definite and certain and adequate indeed.

Let us remind ourselves, therefore, of the only thing we can do or will do. We must depend in every time of national peril, in the future as in the past, not upon a standing army, nor yet upon a reserve army, but upon a citizenry trained and accustomed to arms. It will be right enough, right American policy, based upon our accustomed principles and practices, to provide a system by which every citizen who will volunteer for the training may be made familiar with the use of modern arms, the rudiments of drill and maneuver, and the maintenance and sanitation of camps. We should encourage such training and make it a means of discipline which our young men will learn to value. It is right that we should provide it not only, but that we should make it as attractive as possible, and so induce our young men to undergo it at such times as they can command a little freedom and can seek the physical development they need, for mere health's sake, if for nothing more. Every means by which such things can be stimulated is legitimate, and such a method smacks of true American ideas. It is right, too, that the National Guard of the States should be developed and strengthened by every means which is not inconsistent with our obligations to our own people or with the established policy of our Government. And this, also, not because the time or occasion specially calls for such measures, but because it should be our constant policy to make these provisions for our national peace and safety.

(Source: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/ind...)

Wilson's Second State of the Union, Part Three:

Wilson's Second State of the Union, Part Three:More than this carries with it a reversal of the whole history and character of our polity. More than this, proposed at this time, permit me to say, would mean merely that we had lost our self-possession, that we had been thrown off our balance by a war with which we have nothing to do, whose causes can not touch us, whose very existence affords us opportunities of friendship and disinterested service which should make us ashamed of any thought of hostility or fearful preparation for trouble. This is assuredly the opportunity for which a people and a government like ours were raised up, the opportunity not only to speak but actually to embody and exemplify the counsels of peace and amity and the lasting concord which is based on justice and fair and generous dealing.

A powerful navy we have always regarded as our proper and natural means of defense, and it has always been of defense that we have thought, never of aggression or of conquest. But who shall tell us now what sort of navy to build? We shall take leave to be strong upon the seas, in the future as in the past; and there will be no thought of offense or of provocation in that. Our ships are our natural bulwarks. When will the experts tell us just what kind we should construct-and when will they be right for ten years together, if the relative efficiency of craft of different kinds and uses continues to change as we have seen it change under our very eyes in these last few months ?

But I turn away from the subject. It is not new. There is no new need to discuss it. We shall not alter our attitude toward it because some amongst us are nervous and excited. We shall easily and sensibly agree upon a policy of defense. The question has not changed its aspects because the times are not normal. Our policy will not be for an occasion. It will be conceived as a permanent and settled thing, which we will pursue at all seasons, without haste and after a fashion perfectly consistent with the peace of the world, the abiding friendship of states, and the unhampered freedom of all with whom we deal. Let there be no misconception. The country has been misinformed. We have not been negligent of national defense. We are not unmindful of the great responsibility resting upon us. We shall learn and profit by the lesson of every experience and every new circumstance; and what is needed will be adequately done.

I close, as I began, by reminding you of the great tasks and duties of peace which challenge our best powers and invite us to build what will last, the tasks to which we can address ourselves now and at all times with free-hearted zest and with all the finest gifts of constructive wisdom we possess. To develop our life and our resources; to supply our own people, and the people of the world as their need arises, from the abundant plenty of our fields and our marts of trade to enrich the commerce of our own States and of the world with the products of our mines, our farms, and our factories, with the creations of our thought and the fruits of our character,-this is what will hold our attention and our enthusiasm steadily, now and in the years to come, as we strive to show in our life as a nation what liberty and the inspirations of an emancipated spirit may do for men and for societies, for individuals, for states, and for mankind.

(Source: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/ind...)

Augustus Gardner:

Augustus Gardner:

a Representative from Massachusetts; born in Boston, Mass., November 5, 1865; attended St. Paul’s School, Concord, N.H., and was graduated from Harvard University in 1886; studied law in Harvard Law School, but never practiced, devoting himself to the management of his estate; captain and assistant adjutant general on the staff of Gen. James H. Wilson during the Spanish-American War; member of the State senate 1900 and 1901; elected as a Republican to the Fifty-seventh Congress by special election, to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of United States Representative William H. Moody, and reelected to the eight succeeding Congresses (November 4, 1902-May 15, 1917); resigned from Congress to enter the Army; chairman, Committee on Industrial Arts and Expositions (Fifty-ninth and Sixtieth Congresses); during the First World War served at Governors Island and in Macon, Ga., as colonel in the Adjutant General’s Department, and later was transferred at his own request to the One Hundred and Thirty-first Regiment, United States Infantry, with the rank of major; died at Camp Wheeler, Macon, Ga., January 14, 1918; interment in Arlington National Cemetery.

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustus...

http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/agar...

Gilbert Hitchcock:

Gilbert Hitchcock:

a Representative and a Senator from Nebraska; born in Omaha, Nebr., September 18, 1859; attended the public schools of Omaha and the gymnasium at Baden-Baden, Germany; graduated from the law department of the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor in 1881; admitted to the bar and commenced practice in Omaha, Nebr., in 1882; continued the practice of law until 1885, when he established and edited the Omaha Evening World; purchased the Nebraska Morning Herald in 1889 and consolidated the two into the Morning and Evening World Herald; unsuccessful Democratic candidate for election in 1898 to the Fifty-sixth Congress; elected as a Democrat to the Fifty-eighth Congress (March 4, 1903-March 3, 1905); unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1904 to the Fifty-ninth Congress; elected as a Democrat to the Sixtieth and Sixty-first Congresses (March 4, 1907-March 3, 1911); did not seek renomination in 1910, having become a candidate for the United States Senate; elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate January 18, 1911; reelected in 1916 and served from March 4, 1911, to March 3, 1923; unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1922 and for election in 1930; chairman, Committee on the Philippines (Sixty-third through Sixty-fifth Congresses), Committee on Foreign Relations (Sixty-fifth Congress), Committee on Forest Reservations and Game Protection (Sixty-sixth Congress); resumed newspaper work in Omaha, Nebr.; retired from active business in 1933 and moved to Washington, D.C., where he died on February 3, 1934; interment in Forest Lawn Cemetery, Omaha, Nebr.

(Source: http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gilbert_...

http://nebraskahistory.org/lib-arch/r...

(no image)Gilbert Hitchcock Of Nebraska: Wilson's Floor Leader In The Fight For The Versailles Treaty by Thomas W. Ryley

Birth of a Nation:

Birth of a Nation:

A controversial, explicitly racist, but landmark American film masterpiece - these all describe ground-breaking producer/director D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation (1915). The domestic melodrama/epic originally premiered with the title The Clansman in February, 1915 in Los Angeles, California, but three months later was retitled with the present title at its world premiere in New York, to emphasize the birthing process of the US. The film was based on former North Carolina Baptist minister Rev. Thomas Dixon Jr.'s anti-black, 1905 bigoted melodramatic staged play, The Clansman, the second volume in a trilogy.

Its release set up a major censorship battle over its vicious, extremist depiction of African Americans, although Griffith naively claimed that he wasn't racist at the time. Unbelievably, the film is still used today as a recruitment piece for Klan membership - and in fact, the organization experienced a revival and membership peak in the decade immediately following its initial release. And the film stirred new controversy when it was voted into the National Film Registry in 1993, and when it was voted one of the "Top 100 American Films" (at # 44) by the American Film Institute in 1998.

Film scholars agree, however, that it is the single most important and key film of all time in American movie history - it contains many new cinematic innovations and refinements, technical effects and artistic advancements, including a color sequence at the end. It had a formative influence on future films and has had a recognized impact on film history and the development of film as art. In addition, at almost three hours in length, it was the longest film to date. However, it still provokes conflicting views about its message.

Director Griffith's original budget of $40,000 (expanded to $60,000) quickly ballooned, so Griffith appealed to businessmen and other investors to help finance the film - that eventually cost $110,000! The propagandistic film was one of the biggest box-office money-makers in the history of film, partly due to its exorbitant charge of $2 per ticket - unheard of at the time. This 'first' true blockbuster made $18 million by the start of the talkies. [It was the most profitable film for over two decades, until Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937).]

The subject matter of the film caused immediate criticism by the newly-created National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for its racist and "vicious" portrayal of blacks, its proclamation of miscegenation, its pro-Klan stance, and its endorsement of slavery. As a result, two scenes were cut (a love scene between Reconstructionist Senator and his mulatto mistress, and a fight scene). But the film continued to be renounced as "the meanest vilification of the Negro race." Riots broke out in major cities (Boston, Philadelphia, among others), and it was denied release in many other places (Chicago, Ohio, Denver, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Minneapolis, eight states in total). Subsequent lawsuits and picketing tailed the film for years when it was re-released (in 1924, 1931, and 1938).

The resulting controversy only helped to fuel the film's box-office appeal, and it became a major hit. Even President Woodrow Wilson during a private screening at the White House is reported to have enthusiastically exclaimed: "It's like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all terribly true." To his credit, Griffith later (by 1921) released a shortened, re-edited version of the film without references to the KKK.

In its explicitly caricaturist presentation of the KKK as heroes and Southern blacks as villains and violent rapists and threats to the social order, it appealed to white Americans who subscribed to the mythic, romantic view (similar to Sir Walter Scott historical romances) of the Old Plantation South. Many viewers were thrilled by the love affair between Northern and Southern characters and the climactic rescue scene. The film also thematically explored two great American issues: inter-racial sex and marriage, and the empowerment of blacks. Ironically, although the film was advertised as authentic and accurate, the film's major black roles in the film -- including the Senator's mulatto mistress, the mulatto politican brought to power in the South, and faithful freed slaves -- were stereotypically played and filled by white actors - in blackface. [The real blacks in the film only played in minor roles.]

Its climactic finale, the suppression of the black threat to white society by the glorious Ku Klux Klan, helped to assuage some of America's sexual fears about the rise of defiant, strong (and sexual) black men and the repeal of laws forbidding intermarriage. To answer his critics, director Griffith made a sequel, the magnificent four story epic about human intolerance titled Intolerance (1916). A group of independent black filmmakers released director Emmett J. Scott's The Birth of a Race in 1919, filmed as a response to Griffith's masterwork, with a more positive image of African-Americans, but it was largely ignored. Prolific black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux's first film, the feature-length The Homesteader (1919), and Within Our Gates (1919) more effectively countered the message of Griffith's film.

Its pioneering technical work, often the work of Griffith's under-rated cameraman Billy Bitzer, includes many techniques that are now standard features of films, but first used in this film. Griffith brought all of his experience and techniques to this film from his earliest short films at Biograph, including the following:

-the use of ornate title cards

-special use of subtitles graphically verbalizing imagery

-its own original musical score written for an orchestra

-the introduction of night photography (using magnesium flares)

-the use of outdoor natural landscapes as backgrounds

-the definitive usage of the still-shot

-elaborate costuming to achieve historical authenticity and accuracy

-many scenes innovatively filmed from many different and multiple angles

-the technique of the camera "iris" effect (expanding or contracting circular masks to either reveal and open up a scene, or close down and conceal a part of an image)

-the use of parallel action and editing in a sequence (Gus' attempted rape of Flora, and the KKK rescues of Elsie from Lynch and of Ben's sister Margaret)

-extensive use of color tinting for dramatic or psychological effect in sequences

-moving, traveling or "panning" camera tracking shots

the effective use of total-screen close-ups to reveal intimate expressions

-beautifully crafted, intimate family exchanges

-the use of vignettes seen in "balloons" or "iris-shots" in one portion of a darkened screen

-the use of fade-outs and cameo-profiles (a medium closeup in front of a blurry background)

-the use of lap dissolves to blend or switch from one image to another

-high-angle shots and the abundant use of panoramic long shots

-the dramatization of history in a moving story - an example of an early spectacle or epic film with historical costuming and many historical references (e.g., Mathew Brady's Civil War photographs)

-impressive, splendidly-staged battle scenes with hundreds of extras (made to appear as thousands)

-extensive cross-cutting between two scenes to create a montage-effect and generate excitement and suspense (e.g., the scene of the gathering of the Klan)

-expert story-telling, with the cumulative building of the film to a dramatic climax

The film looks remarkably genuine and authentic, almost of documentary quality (like Brady's Civil War photographs), vividly reconstructing a momentous time period in history - and it was made only 50 years after the end of the Civil War. Its story includes the events leading up to the nation's split; the Civil War era; the period from the end of the Civil War to Lincoln's assassination; the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era detailing the struggle over the control of Congress during Andrew Johnson's presidency and actions of the Radical Republicans to enfranchise the freed slaves, and the rise of the KKK.

(Source: http://www.filmsite.org/birt.html)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Birt...

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0004972/

Thomas Dixon Jr.

Thomas Dixon Jr. Michael R. Hurwitz

Michael R. Hurwitz

Thomas Dixon:

Thomas Dixon:

Born in the rural North Carolina Piedmont a year before the Civil War ended, Thomas Dixon lived to see the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and the end of World War II. Between 1902 and 1939 he published 22 novels, as well as numerous plays, screenplays, books of sermons, and miscellaneous nonfiction. Educated at Wake Forest and Johns Hopkins, Dixon was a lawyer, state legislator, preacher, novelist, playwright, actor, lecturer, real-estate speculator, and movie producer. Familiar to three presidents and such notables as John D. Rockefeller, he made and lost millions, ending up an invalid court clerk in Raleigh, N.C.

Paradoxically, Dixon is among the most dated and most contemporary of southern writers. In genre an early 19th-century romancer, thematically Dixon argued for three interrelated beliefs still current in southern life: the need for racial purity, the sanctity of the family centered on a traditional wife and mother, and the evil of socialism.

In the Klan trilogy—The Leopard's Spots (1902), The Clansman (1905), The Traitor (1907)— and in The Sins of the Fathers (1912), Dixon presents racial conflict as an epic struggle, with the future of civilization at stake. Although Dixon personally condemned slavery and Klan activities after Reconstruction ended, he argued that blacks must be denied political equality because that leads to social equality and miscegenation, thus to the destruction of both family and civilized society. Throughout his work, white southern women are the pillars of family and society, the repositories of all human idealism. The Foolish Virgin (1915) and The Way of a Man (1919) attack women's suffrage because women outside the home become corrupted; with the sacred vessels shattered, social morality is lost. In his trilogy on socialism—The One Woman (1903), Comrades (1909), The Root of Evil (1911)—he attacks populist socialism expressed in such works as Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward, arguing that it is impossible for all classes to be equal in a society. Dixon's last novel, The Flaming Sword (1939), written just before he suffered a crippling cerebral hemorrhage, combines the threats of socialism and racial equality, presenting blacks as communist dupes attempting the overthrow of the United States. Through all his work runs an impassioned defense of conservative religious values.

Young Dixon's religious and political beliefs were melded in a crucible shaped by his region's military defeat and economic depression and by the fiercely independent, Scotch-Irish Presbyterian faith of the North Carolina highlands. As a student reading Darwin, Huxley, and Spencer, he suffered a brief period of religious doubt. But his faith rebounded stronger than ever, and Dixon sought the grandest pulpit he could find. He abandoned a successful Baptist ministry in New York for the larger nondenominational audience he could reach as a lecturer and, after the success of The Leopard's Spots, as a novelist and playwright. With the movie Birth of a Nation (based on The Clansman), Dixon believed he had found the ideal medium to educate the masses, to bring them to political and religious salvation. Although his work is seldom read today, both in his themes and as a political preacher seeking a national congregation through mass media, Thomas Dixon clearly foreshadowed the politicized television evangelists of the modern South.

(Source: http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/dixo...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_D....

Thomas Dixon Jr.

Thomas Dixon Jr. Michele K. Gillespie

Michele K. Gillespie Anthony Slide

Anthony Slide

Horace Lurton:

Horace Lurton:

was born in Newport, Kentucky, on February 26, 1844, and raised in Clarksville, Tennessee. He attended the University of Chicago in 1860 but joined the Confederate Army at the outbreak of the Civil War. Captured by Union soldiers, he soon escaped, but was recaptured and released from prison just before the War ended. Lurton resumed his studies and was graduated from Cumberland University Law School in 1867. He returned to Clarksville and began the practice of law. In 1875, at the age of thirty-one, he was appointed by the Governor of Tennessee to the Sixth Chancery Division of Tennessee and became the youngest Chancellor in the history of the state. He resigned after three years and resumed his law practice. Lurton was elected to the Tennessee Supreme Court in 1886, and became its Chief Judge in 1893. Later that year, President Grover Cleveland appointed Lurton to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, where he served for sixteen years. President William H. Taft nominated Lurton to the Supreme Court of the United States on December 20, 1909. The Senate confirmed the appointment on January 3, 1910. Lurton served on the Supreme Court for four years. He died on July 12, 1914, at the age of seventy.

(Source: http://www.supremecourthistory.org/hi...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horace_H...

http://www.fjc.gov/servlet/nGetInfo?j...

http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entr...

Edith Galt:

Edith Galt:

Edith Bolling Wilson, Woodrow Wilson's second wife, is sometimes described as America's first woman President because of the role she played after the President's massive stroke in October 1919. Choosing to admit or turn away visitors and deciding what papers Wilson did or did not see, she was a controversial figure at the time and has remained so ever since. For her part, Edith Wilson described her role as that of a steward. She wrote in her 1939 memoirs that as First Lady, she "never made a single decision regarding the disposition of public affairs." In fact, she claimed powers over only "what was important and what was not" and "when to present matters to my husband."

Edith was introduced to the President in early 1915, about six months after the death of Ellen Axson Wilson, his first wife. Wilson liked her at once and began sharing state secrets with her in an effort to charm her. After a brief but passionate courtship, the two became secretly engaged. But Wilson's political advisers felt that his remarriage less than a year after the death of Ellen Wilson would offend the American public and damage his reelection prospects; they even concocted a scheme to prevent him from marrying Edith. Despite their machinations, the couple was married in December 1915.

As First Lady, Edith, far more than Ellen Wilson, invested herself in the President's political affairs. She became his confidante and personal assistant, particularly attempting to break off his relations with those she believed had tried to torpedo her marriage to the President. She was familiar with the pressing issues of the administration, including the war

raging in Europe. Not greatly interested in the traditional role of the First Lady, she hired a secretary to meet the demands of her limited social calendar. She then used the American declaration of war in 1917 as an excuse to eliminate official entertaining altogether. Public tours of the White House ended, the annual Easter Egg Roll and New Year's Day reception ceased, and formal dinners were kept to a minimum.

Throughout the war, the First Lady, who preferred to be called "Mrs. Woodrow Wilson," set an example for economy and patriotism. Like other American housewives, she wore thrift clothing, observed rationing, and "Hooverized" the White House, adopting "meatless Mondays" and "wheatless Wednesdays." Instead of paying a gardening crew to maintain the White House lawn, Edith borrowed twenty sheep from a nearby farm and donated the wool to charitable auctions aiding the American cause -- sales of the auctioned wool ultimately netted $50,000. She knitted trench helmets; sewed pajamas, pillowcases, and blankets; promoted war bonds; responded to soldiers' mail; named thousands of vessels; and volunteered with the Red Cross at Union Station. Unlike the typical American homemaker, however, Edith Wilson also helped the war effort by decoding military messages and giving advice to the President on his dealings with Congress.

At the war's end, the First Lady went to Europe with the President. She urged the President to include more Republicans on the commission, but Wilson demurred. In Europe, some of the President's popularity also rubbed off on the First Lady. She enjoyed her status and spent her time in France touring hospitals and visiting American troops. In February 1919, when Wilson presented the plan for the League of Nations to the peace conference, she persuaded the presiding officer, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, to let her attend the session.

When Wilson decided, in the late summer of 1919, to travel across the country speaking in support of the League of Nations, Edith worried that his health was too frail to stand the strain. As she feared, he collapsed on September 25, and she rushed him back to Washington, where he suffered a massive stroke on October 2. Although the President was paralyzed and unable to carry out the duties of his office, Edith insisted that he must not resign because she believed that losing office would kill him. This was the single most important decision she made during Wilson's illness, and from it followed all the rest -- her concealment of the severity of his debility from the cabinet and the press, her determination that almost no one be admitted to the sickroom, her screening of the papers and issues that would be brought to his attention, and her assumption of the role of secretary, reporting the President's decisions to government officials. Until January 1920, Wilson had almost no contact with anyone outside his circle of family and doctors; he did not meet with his cabinet until April 1920.

Edith Wilson never intended to usurp her husband's power nor to become the "first woman President." As she told Wilson's doctor, "I am not thinking of the country now, I am thinking of my husband." But in seeking to protect the man she loved, she did in fact assume a major political role. In excluding visitors and deciding which issues should be presented to him, she made political decisions without meaning to do so. At bottom, however, the fault was not hers -- she merely loved her husband -- it was a deficiency of the American political system that, until the adoption of the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the Constitution in 1967, made no provision for the disability of the President.

(Source: http://millercenter.org/president/wil...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_Bo...

http://www.whitehouse.gov/about/first...

http://www.firstladies.org/biographie...

(no image)My Memoir by Edith Bolling Wilson

Kristie Miller

Kristie Miller Phyllis Lee Levin

Phyllis Lee Levin

Sinking of Lusitania:

Sinking of Lusitania:

The British ocean liner RMS Lusitania, famous for its luxurious accommodations and speed capability, primarily ferried people and goods across the Atlantic Ocean between the United States and Great Britain. On May 1, 1915, the Lusitania left port in New York for Liverpool to make her 202nd trip across the Atlantic. On board were 1,959 people, 159 of whom were Americans.

Since the outbreak of World War I, ocean voyage had become dangerous. Each side hoped to blockade the other, thus prevent any war materials getting through. German U-boats (submarines) stalked British waters, continually looking for enemy vessels to sink.

All ships headed to Great Britain were instructed to be on the lookout for U-boats and take precautionary measures such as travel at full speed and make zigzag movements. Unfortunately, on May 7, 1915, Captain William Thomas Turner slowed the Lusitania down because of fog and traveled in a predictable line.

Approximately 14 miles off the coast of Southern Ireland at Old Head of Kinsale, neither the captain nor any of his crew realized that the German U-boat, U-20, had already spotted and targeted them. At 1:40 p.m., the U-boat launched a torpedo. The torpedo hit the starboard (right) side of the Lusitania. Almost immediately, another explosion rocked the ship.