The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

The British Are Coming

AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY WAR

>

SPOTLIGHTED BOOK: THE BRITISH ARE COMING: THE WAR FOR AMERICA, LEXINGTON TO PRINCETON, 1775-1777 (THE REVOLUTION TRILOGY #1) - GLOSSARY ~ (Spoiler Thread)

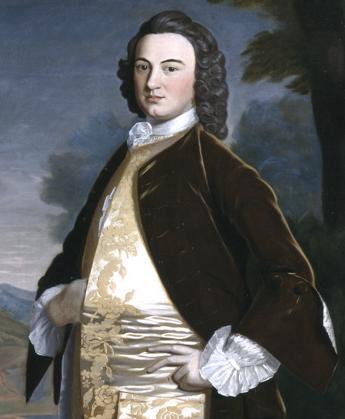

George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was born into a mildly prosperous Virginia farming family in 1732. After his father died when George was eleven, George's mother, Mary, a tough and driven woman, struggled to hold their home together with the help of her two sons from a previous marriage. Although he never received more than an elementary school education, young George displayed a gift for mathematics. This knack for numbers combined with his quiet confidence and ambition caught the attention of Lord Fairfax, head of one of the most powerful families in Virginia. While working for Lord Fairfax as a surveyor at the age of sixteen, the young Washington traveled deep into the American wilderness for weeks at a time.

British Army Service

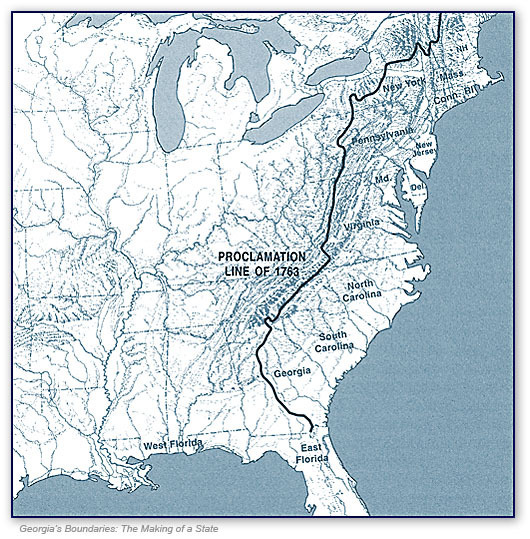

Tragedy struck the young man with the death of his half brother Lawrence, who had guided and mentored George after his father's death. George inherited Mount Vernon from his brother, living there for the rest of his life. At the time, England and France were enemies in America, vying for control of the Ohio River Valley. Holding a commission in the British army, Washington led a poorly trained and equipped force of 150 men to build a fort on the banks of the Ohio River. On the way, he encountered and attacked a small French force, killing a French minister in the process. The incident touched off open fighting between the British and the French, and in one fateful engagement, the British were routed by the superior tactics of the French.

Although hailed as a hero in the colonies when word spread of his heroic valor and leadership against the French, the Royal government in England blamed the colonials for the defeat. Angry at the lack of respect and appreciation shown to him, Washington resigned from the army and returned to farming in Virginia. In 1759, he married Martha Custis, a wealthy widow, and thereafter devoted his time to running the family plantation. By 1770, Washington had emerged as an experienced leader—a justice of the peace in Fairfax County, a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, and a respected vestryman (a lay leader in his church). He also was among the first prominent Americans to openly support resistance to England's new policies of taxation and strict regulation of the colonial economy (the Navigation Acts) beginning in the early 1770s.

A Modest Military Leader

Washington was elected by the Virginia legislature to both the First and the Second Continental Congress, held in 1774 and 1775. In 1775, after local militia units from Massachusetts had engaged British troops near Lexington and Concord, the Second Continental Congress appointed Washington commander of all the colonial forces. Showing the modesty that was central to his character, and would later serve the young Republic so well, Washington proclaimed, "I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with."

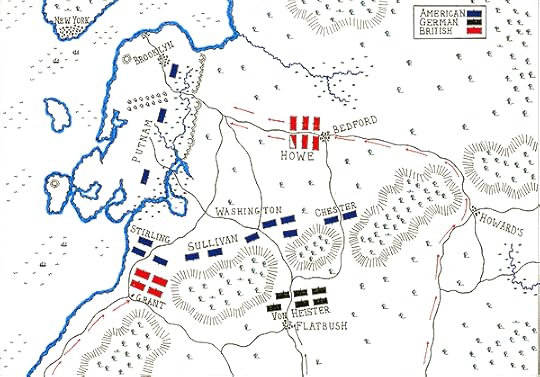

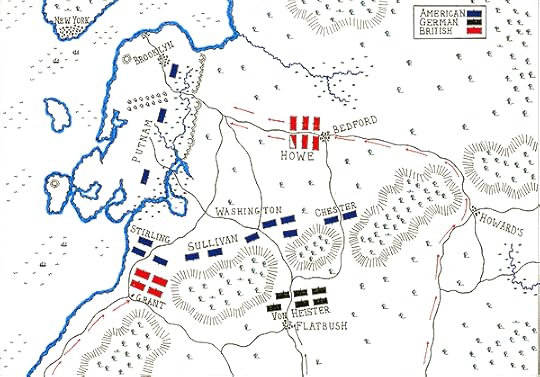

After routing the British from Boston in the spring of 1776, Washington fought a series of humiliating battles in a losing effort to defend New York. But on Christmas Day that same year, he led his army through a ferocious blizzard, crossed the Delaware into New Jersey, and defeated the Hessian forces at Trenton. In May 1778, the French agreed to an alliance with the Americans, marking the turning point of the Revolution. Washington knew that one great victory by his army would collapse the British Parliament's support for its war against the colonies. In October 1781, Washington's troops, assisted by the French Navy, defeated Cornwallis at Yorktown. By the following spring the British government was ready to end hostilities.

King Washington?

Following the war, Washington quelled a potentially disastrous bid by some of his officers to declare him king. He then returned to Mount Vernon and the genteel life of a tobacco planter, only to be called out of retirement to preside at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. His great stature gave credibility to the call for a new government and insured his election as the first President of the United States. Keenly aware that his conduct as President would set precedents for the future of the office, he carefully weighed every step he took. He appointed Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton to his cabinet. Almost immediately, these two men began to quarrel over a wide array of issues, but Washington valued them for the balance they lent his cabinet. Literally the "Father of the Nation," Washington almost single-handedly created a new government—shaping its institutions, offices, and political practices.

Although he badly wanted to retire after the first term, Washington was unanimously supported by the electoral college for a second term in 1792. Throughout both his terms, Washington struggled to prevent the emergence of political parties, viewing them as factions harmful to the public good. Nevertheless, in his first term, the ideological division between Jefferson and Hamilton deepened, forming the outlines of the nation's first party system. This system was composed of Federalists, who supported expansive federal power and Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, followers of Thomas Jefferson's philosophy of states' rights and limited federal power. Washington generally backed Hamilton on key issues, such as the funding of the national debt, the assumption of state debts, and the establishment of a national bank.

Throughout his two terms, Washington insisted on his power to act independent of Congress in foreign conflicts, especially when war broke out between France and England in 1793 and he issued a Declaration of Neutrality on his own authority. He also acted decisively in putting down a rebellion by farmers in western Pennsylvania who protested a federal whiskey tax (the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794). After he left office, exhausted and discouraged over the rise of political factions, Washington returned to Mount Vernon, where he died almost three years later.

Historians agree that no one other than George Washington could have held the disparate colonies and, later, the struggling young Republic together. To the Revolution's last day, Washington's troops were ragged, starving, and their pay was months in arrears. In guiding this force during year after year of humiliating defeat to final victory, more than once paying his men out of his own pocket to keep them from going home, Washington earned the unlimited confidence of those early citizens of the United States. Perhaps most importantly, Washington's balanced and devoted service as President persuaded the American people that their prosperity and best hope for the future lay in a union under a strong but cautious central authority. His refusal to accept a proffered crown and his willingness to relinquish the office after two terms established the precedents for limits on the power of the presidency. Washington's profound achievements built the foundations of a powerful national government that has survived for more than two centuries.

(Source: http://millercenter.org/president/was...)

More:

http://www.mountvernon.org/meet-georg...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_W...

http://www.whitehouse.gov/about/presi...

http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/

http://www.history.org/almanack/peopl...

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/...

http://www.earlyamerica.com/lives/gwl...

by

by

Logan Beirne

Logan Beirne by

by

Ron Chernow

Ron Chernow by

by

David Hackett Fischer

David Hackett Fischer by James Thomas Flexner (no photo)

by James Thomas Flexner (no photo) by

by

Joseph J. Ellis

Joseph J. Ellis by Willard Sterne Randall (no photo)

by Willard Sterne Randall (no photo) by Richard Brookhiser (no photo)

by Richard Brookhiser (no photo) by

by

Edward G. Lengel

Edward G. Lengel by

by

Henry Wiencek

Henry Wiencek

John Adams

John Adams

Adams began his education in a common school in Braintree. He secured a scholarship to Harvard and graduated at the age of 20.

He apprenticed to a Mr. Putnam of Worcester, who provided access to the library of the Attorney General of Massachusetts, and was admitted to the Bar in 1761. He participated in an outcry against Writs of Assistance. Adams became a prominent public figure in his activities against the Stamp Act, in response to which he wrote and published a popular article, Essay on the Canon and Feudal Law. He was married on Oct. 25, 1764 and moved to Boston, assuming a prominent position in the patriot movement. He was elected to the Massachusetts Assembly in 1770, and was chosen one of five to represent the colony at the First Continental Congress in 1774.

Again in the Continental Congress, in 1775, he nominated Washington to be commander-in-chief on the colonial armies. Adams was a very active member of congress, he was engaged by as many as ninety committees and chaired twenty-five during the second Continental Congress. In May of 1776, he offered a resolution that amounted to a declaration of independence from Gr. Britain. He was shortly thereafter a fierce advocate for the Declaration drafted by Thos. Jefferson. Congress then appointed him ambassador to France, to replace Silas Dean at the French court. He returned from those duties in 1779 and participated in the framing of a state constitution for Massachusetts, where he was further appointed Minister plenipotentiary to negotiate a peace, and form a commercial treaty, with Gr. Britain. In 1781 he participated with Franklin, Jay and Laurens, in development of the Treaty of Peace with Gr. Britain and was a signer of that treaty, which ended the Revolutionary War, in 1783. He was elected Vice President of the United States under Geo. Washington in 1789, and was elected President in 1796. Adams was a Federalist and this made him an arch-rival of Thos. Jefferson and his Republican party. The discord between Adams and Jefferson surfaced many times during Adams' (and, later, Jefferson's) presidency. This was not a mere party contest. The struggle was over the nature of the office and on the limits of Federal power over the state governments and individual citizens. Adams retired from office at the end of his term in 1801. He was elected President of a convention to reform the constitution of Massachusetts in 1824, but declined the honor due to failing health.

He died on July 4, 1826 (incidentally, within hours of the death of Thos. Jefferson.) His final toast to the Fourth of July was "Independence Forever!" Late in the afternoon of the Fourth of July, just hours after Jefferson died at Monticello, Adams, unaware of that fact, is reported to have said, "Thomas Jefferson survives."

(Source: http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/...)

More:

http://millercenter.org/president/ada...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Adams

http://www.whitehouse.gov/about/presi...

http://www.nps.gov/adam/john-adams-bi...

http://americanhistory.about.com/od/j...

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/...

http://www.masshist.org/adams/biograp...

by

by

David McCullough

David McCullough by Richard Alan Ryerson (no photo)

by Richard Alan Ryerson (no photo)

by

by

Joseph J. Ellis

Joseph J. Ellis

by

by

John Ferling

John Ferling by Page Smith (no photo)

by Page Smith (no photo)

James Madison

James Madison

Born on March 16, 1751 at his grandmother’s home in Port Conway, Virginia, James Madison was the eldest of the twelve children of James Madison Sr. and Nelly Conway Madison. His early years were spent at Mount Pleasant, the first house built on the Montpelier plantation. At age 12, Madison’s father sent him to Donald Robertson’s school in King and Queen County. There Madison studied arithmetic and geography, learned Latin and Greek, acquired a reading knowledge of French, and began to study algebra and geometry. Madison never forgot his teacher, later acknowledging “all that I have been in life I owe largely to that man.”

After further study with a private tutor at Montpelier, Madison enrolled in college at the College of New Jersey (today known as Princeton University), earning a bachelor’s degree in 1771. He continued his education at Princeton through the next winter, studying Hebrew and ethics . Madison overworked himself in order to complete two years of coursework in one. In poor health, he returned to Montpelier, where he continued to read on a variety of topics, particularly law.

Early Political Career

As tensions increased between Great Britain and the colonies, Madison “entered with the prevailing zeal into the American Cause,” as he later wrote in an autobiographical sketch. Madison gained his first experiences in politics when he was appointed to the Orange Country Committee of Safety in 1774 and was elected to represent Orange in the 1776 Virginia Convention. Madison joined the local militia, but after participating in their exercises, he realized that “the unsettled state of his health and the discourageing feebleness of his constitution” would prevent him from serving in the military.

Madison continued to pursue a political career. After losing the 1777 election for the Virginia Assembly, he was appointed to the Council of State (1777-79). He served as Virginia’s representative to the Continental Congress from 1780 to 1783, and as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates from 1784 to 1787. He returned to Congress in 1787.

Constitutional Convention

In 1787, the Continental Congress called for a Federal Convention to consider revisions to the Articles of Confederation. Madison gave serious thought to the problems facing the nation and made specific proposals for devising a new constitution which, when presented by his state’s delegation, became known as the Virginia Plan. This was the first plan considered by the Convention, and many of its elements were incorporated into the Constitution in its final form. Madison worked tirelessly to encourage the states to ratify the new Constitution, writing 29 of the 85 anonymous essays comprising The Federalist.

Madison was elected to Congress under the new Constitution, where he served from 1789 until 1797. During this period, Madison met and married the widowed Dolley Payne Todd and, by 1797, described himself as “wearied with public life” and eager to “indulge his relish for the intellectual pleasures ... and the pursuits of rural life.” He looked forward to enjoying life at Montpelier with “a partner who favoured these views, and added every happiness to his life which female merit could impart.”

In 1799, Madison returned to politics when he was elected to the Virginia Assembly. In the 1798-99 session of the Virginia legislature, Madison’s anonymous Virginia Resolutions, a response to the federal Alien and Sedition Acts, were adopted. In the 1799-1800 session, Madison served in the House of Delegates where he wrote his Report of 1800, a defense of the Virginia Resolutions. He was appointed to the Electoral College for the election of 1800, an election famously thrown to the House of Representatives when the Electoral College vote was tied between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. The House selected Jefferson, Madison’s longtime friend and neighbor.

Secretary of State & Presidency

Early in his term, Jefferson appointed Madison as his secretary of state (1801-09). Responsible for foreign affairs and some domestic duties, Madison oversaw significant changes to the young nation, including the Barbary Wars, a major embargo, the Lewis and Clark expeditions, and the Louisiana Purchase, which enlarged the nation by 828,000 square miles.

At the conclusion of Jefferson’s second term, Madison was inaugurated as the fourth president of the United States (1809-17), inheriting the unresolved issues stemming from the war between France and Great Britain. Each nation attempted to prevent its rival from trading with the United States. Madison called on Congress to declare war against Great Britain in 1812. Opponents mocked the war as “Mr. Madison’s War” and found fault with his leadership. By war’s end, however, a new spirit of nationalism had emerged, and Madison left office in high regard.

Retirement to Montpelier

Following his retirement from the presidency, Madison took part in one final political event: the 1829 Virginia Convention that revised the state constitution. Madison’s retirement years were occupied with organizing and editing his papers from the 1787 Constitutional Convention, keeping up correspondence, and receiving the many visitors who journeyed to meet the Father of the Constitution.

James Madison died at Montpelier on June 28, 1836. In his eulogy, friend and neighbor Governor James Barbour expressed “hope that the life of Madison ... may become a pillar of light by which some future patriot may reconduct his countrymen to their lost inheritance.”

(Source: http://www.montpelier.org/james-and-d...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Ma...

http://millercenter.org/president/mad...

http://www.whitehouse.gov/about/presi...

http://www.montpelier.org/

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/...

http://www.thejamesmadisonmuseum.org/

http://www.americanpresidents.org/pre...

by Ralph Louis Ketcham (no photo)

by Ralph Louis Ketcham (no photo) by Richard Brookhiser (no photo)

by Richard Brookhiser (no photo) by

by

Garry Wills

Garry Wills by Richard Labunski (no photo)

by Richard Labunski (no photo) by

by

Kevin R.C. Gutzman

Kevin R.C. Gutzman by Robert Allen Rutland (no photo)

by Robert Allen Rutland (no photo) by

by

James Madison

James Madison

message 5:

by

Jerome, Assisting Moderator - Upcoming Books and Releases

(last edited May 04, 2020 03:11AM)

(new)

-

added it

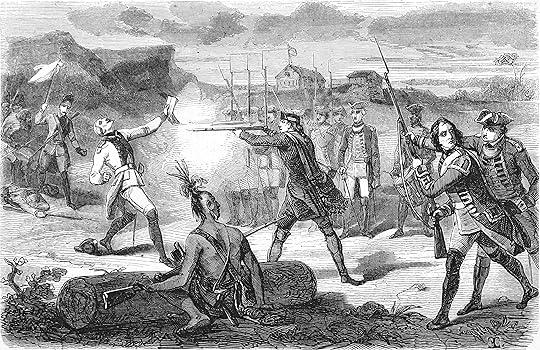

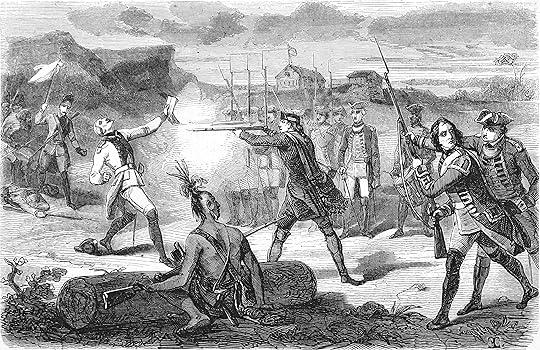

Chief Tanacharison

Tanacharison or Tanaghrisson (c. 1700 – 4 October 1754) was an American Indian leader who played a pivotal role in the beginning of the French and Indian War. He was known to European-Americans as the Half King, a title also used to describe several other historically important American Indian leaders. His name has been spelled in a variety of ways.

Early life

Little is known of Tanacharison's early life. He may have been born into the Catawba tribe about 1700 near what is now Buffalo, New York. As a child, he was taken captive by the French and later adopted into the Seneca tribe, one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. He would later claim that the French boiled and ate his father. His early years were spent on the southeastern shore of Lake Erie in what is now western New York state.

Becoming a leader

Tanacharison first appears in historical records in 1747, living in Logstown (near present Ambridge, Pennsylvania), a multi-ethnic village about 20 miles (30 kilometers) downstream from the forks of the Ohio River. Those Iroquois who had migrated to the Ohio Country were generally known as "Mingos", and Tanacharison emerged as a Mingo leader at this time. He also represented the Six Nations at the 1752 Treaty of Logstown, where he was referred to as "Thonariss, called by the English the half King". At this treaty, he speaks on behalf of the Six Nations' Grand Council, but also makes clear that the Council's ratification was required, in accordance with the Iroquois system of government.

According to the traditional interpretation, the Grand Council had named Tanacharison as leader or "half-king" (as a sort of viceroy) to conduct diplomacy with other tribes, and to act as spokesman to the British on their behalf. However, some modern historians have doubted this interpretation, asserting that Tanacharison was merely a village leader, whose actual authority extended no further than his village. In this view, the title "half king" was likely a British invention, and his "subsequent lofty historical role as a Six Nations 'regent' or 'viceroy' in the Ohio Country was the product of later generations of scholars."

French and Indian War

In 1753, the French began the military occupation of the Ohio Country, driving out British traders and constructing a series of forts. British colonies, however, also claimed the Ohio Country. Robert Dinwiddie, the lieutenant governor of Virginia, sent a young George Washington to travel to the French outposts and demand that the French vacate the Ohio Country. On his journey, Washington's party stopped at Logstown to ask Tanacharison to accompany them as a guide and as a "spokesman" for the Ohio Indians. Tanacharison agreed to return the symbolic wampum he had received from French captain Philippe de Joincaire. Joincaire's first reaction, on learning of this double cross, was to mutter of Tanacharison, "He is more English than the English." But Joincaire masked his anger and insisted that Tanacharison join him in a series of toasts. By the time the keg was empty, Tanacharison was too drunk to hand back the wampum.Tanacharison traveled with Washington to meet with the French commander of Fort Le Boeuf in what is now Waterford, Pennsylvania. The French refused to vacate, however, and to Washington's great consternation, they tried to court Tanacharison as an ally. Although fond of their brandy, he remained a strong francophobe.

Tanacharison had requested that the British construct a "strong house" at the Forks of the Ohio and early in 1754 he placed the first log of an Ohio Company stockade there, railing against the French when they captured it. He was camped at Half King's Rock on May 27, 1754 when he learned of a nearby French encampment and sent word urging an attack to Washington at the Great Meadows, about five miles (8 km) east of Chestnut Ridge in what is now Fayette County, Pennsylvania (near Uniontown). Washington immediately ordered 40 men to join Tanacharison and at sunset followed with a second group, seven of whom got lost in heavy rain that night. It was dawn before Washington reached the Half King's Rock.

After a hurried war council, the English and Tanacharison's eight or nine warriors set off to surround and attack the French, who quickly surrendered. The French commander, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, was among the wounded. With the French words, "Tu n'es pas encore mort, mon père!" (Thou are not yet dead, my father), Tancharison sank his tomahawk in Jumonville's skull, washed his hands with the brains, "and scalped him". Only one of the wounded French soldiers was not killed and scalped among a total of ten dead, 21 captured, and one missing, a man named Monceau who had wandered off to relieve himself that morning.

Monceau witnessed the French surrender before walking barefoot to the Monongahela River and paddling down it to report to Contrecoeur, commanding at Fort Duquesne. Tanacharison sent a messenger to Contrecoeur the following day with news that the British had shot Jumonville and but for the Indians would have killed all the French. A third and accurate account of the Jumonville Glen encounter was told to Jumonville's half-brother, Captain Louis Coulon de Villiers, by a deserter at the mouth of Redstone Creek during his expedition to avenge his brother's murder.

Washington was without Indian allies at the battle of Fort Necessity, his hastily erected stockade at the Great Meadows. Tanacharison scornfully called it "that little thing upon the meadow" and complained that Washington would not listen to advice and treated the Indians like slaves. He and another Seneca leader, Queen Aliquippa, had taken their people to Wills Creek. Outnumbered and with supplies running low, Washington surrendered the fort, later blaming Captains George Croghan and Andrew Montour for "involving the country in great calamity".

Tanacharison was "one of the sachems who had confirmed Croghan in his land grant of 1749" (Wainwright, 49), 200,000 acres minus about two square miles at the Forks of the Ohio for a British Fort. Thomas Penn and Pennsylvania planned to build a stone fort, but Croghan realized that his deeds would be invalid if in Pennsylvania and had Andrew Montour testify before the Assembly in 1751 that the Indians did not want the fort, that it was all Croghan's idea, scuttling the project.

In 1752 Croghan was on the Indian council that granted Virginia's Ohio Company permission to build the fort. Tanacharison's introduction of Croghan to the Virginia commissioners is further evidence that Croghan organized and led the 1748 Ohio Indian Confederation that Pennsylvania recognized as independent of the Six Nations and appointed Croghan as the colony's representative in negotiations.

Brethren, it is a great while since our brother, the Buck (meaning Mr. George Croghan)has been doing business between us, & our brother of Pennsylvania, but we understand he does not intend to do any more, so I now inform you that he is approv'd of by our Council at Onondago, for we sent to them to let them know how he has helped us in our councils here and to let you & him know that he is one of our people and shall help us still & be one of our council, I deliver him this string of wampum.

The Ohio Company fort was surrendered to the French by Croghan's half-brother, Edward Ward, and commanded by his business partner, William Trent, but Croghan's central role in these events remains suppressed, as he himself was in 1777, when Pittsburgh's president judge, Committee of Safety chairman, and person keeping the Ohio Indians pacificed since Pontiac's Rebellion was declared a traitor by General Edward Hand and exiled from the frontier.

It was to Croghan's Aughwick plantation that Tanacharison and Queen Aliquippa took their people in 1754 where the old queen died and Tanacharison became seriously ill and was taken to John Harris.

Tanacharison moved his people east to the Aughwick Valley near present Shirleysburg, Pennsylvania. He would take no active part in the remainder of the war. He died of pneumonia on October 4, 1754 on the farm of John Harris at Paxtang, Pennsylvania (near present-day Harrisburg, Pennsylvania).

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tanachar... )

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_o...

http://www.shmoop.com/french-indian-w...

http://www.helium.com/items/1130288-c...

http://burnpit.legion.org/2010/05/bat...

http://www.offthebeatenpath.ws/Battle...

http://suite101.com/article/the-battl...

by Walter R. Borneman (no photo)

by Walter R. Borneman (no photo)

by Fred Anderson (no photo)

by Fred Anderson (no photo)

by William M. Fowler Jr. (no photo)

by William M. Fowler Jr. (no photo)

by Ruth Sheppard (no photo)

by Ruth Sheppard (no photo)

by Jesse Russell (no photo)

by Jesse Russell (no photo)

by Neville B. Craig (no photo)

by Neville B. Craig (no photo)

Tanacharison or Tanaghrisson (c. 1700 – 4 October 1754) was an American Indian leader who played a pivotal role in the beginning of the French and Indian War. He was known to European-Americans as the Half King, a title also used to describe several other historically important American Indian leaders. His name has been spelled in a variety of ways.

Early life

Little is known of Tanacharison's early life. He may have been born into the Catawba tribe about 1700 near what is now Buffalo, New York. As a child, he was taken captive by the French and later adopted into the Seneca tribe, one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. He would later claim that the French boiled and ate his father. His early years were spent on the southeastern shore of Lake Erie in what is now western New York state.

Becoming a leader

Tanacharison first appears in historical records in 1747, living in Logstown (near present Ambridge, Pennsylvania), a multi-ethnic village about 20 miles (30 kilometers) downstream from the forks of the Ohio River. Those Iroquois who had migrated to the Ohio Country were generally known as "Mingos", and Tanacharison emerged as a Mingo leader at this time. He also represented the Six Nations at the 1752 Treaty of Logstown, where he was referred to as "Thonariss, called by the English the half King". At this treaty, he speaks on behalf of the Six Nations' Grand Council, but also makes clear that the Council's ratification was required, in accordance with the Iroquois system of government.

According to the traditional interpretation, the Grand Council had named Tanacharison as leader or "half-king" (as a sort of viceroy) to conduct diplomacy with other tribes, and to act as spokesman to the British on their behalf. However, some modern historians have doubted this interpretation, asserting that Tanacharison was merely a village leader, whose actual authority extended no further than his village. In this view, the title "half king" was likely a British invention, and his "subsequent lofty historical role as a Six Nations 'regent' or 'viceroy' in the Ohio Country was the product of later generations of scholars."

French and Indian War

In 1753, the French began the military occupation of the Ohio Country, driving out British traders and constructing a series of forts. British colonies, however, also claimed the Ohio Country. Robert Dinwiddie, the lieutenant governor of Virginia, sent a young George Washington to travel to the French outposts and demand that the French vacate the Ohio Country. On his journey, Washington's party stopped at Logstown to ask Tanacharison to accompany them as a guide and as a "spokesman" for the Ohio Indians. Tanacharison agreed to return the symbolic wampum he had received from French captain Philippe de Joincaire. Joincaire's first reaction, on learning of this double cross, was to mutter of Tanacharison, "He is more English than the English." But Joincaire masked his anger and insisted that Tanacharison join him in a series of toasts. By the time the keg was empty, Tanacharison was too drunk to hand back the wampum.Tanacharison traveled with Washington to meet with the French commander of Fort Le Boeuf in what is now Waterford, Pennsylvania. The French refused to vacate, however, and to Washington's great consternation, they tried to court Tanacharison as an ally. Although fond of their brandy, he remained a strong francophobe.

Tanacharison had requested that the British construct a "strong house" at the Forks of the Ohio and early in 1754 he placed the first log of an Ohio Company stockade there, railing against the French when they captured it. He was camped at Half King's Rock on May 27, 1754 when he learned of a nearby French encampment and sent word urging an attack to Washington at the Great Meadows, about five miles (8 km) east of Chestnut Ridge in what is now Fayette County, Pennsylvania (near Uniontown). Washington immediately ordered 40 men to join Tanacharison and at sunset followed with a second group, seven of whom got lost in heavy rain that night. It was dawn before Washington reached the Half King's Rock.

After a hurried war council, the English and Tanacharison's eight or nine warriors set off to surround and attack the French, who quickly surrendered. The French commander, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, was among the wounded. With the French words, "Tu n'es pas encore mort, mon père!" (Thou are not yet dead, my father), Tancharison sank his tomahawk in Jumonville's skull, washed his hands with the brains, "and scalped him". Only one of the wounded French soldiers was not killed and scalped among a total of ten dead, 21 captured, and one missing, a man named Monceau who had wandered off to relieve himself that morning.

Monceau witnessed the French surrender before walking barefoot to the Monongahela River and paddling down it to report to Contrecoeur, commanding at Fort Duquesne. Tanacharison sent a messenger to Contrecoeur the following day with news that the British had shot Jumonville and but for the Indians would have killed all the French. A third and accurate account of the Jumonville Glen encounter was told to Jumonville's half-brother, Captain Louis Coulon de Villiers, by a deserter at the mouth of Redstone Creek during his expedition to avenge his brother's murder.

Washington was without Indian allies at the battle of Fort Necessity, his hastily erected stockade at the Great Meadows. Tanacharison scornfully called it "that little thing upon the meadow" and complained that Washington would not listen to advice and treated the Indians like slaves. He and another Seneca leader, Queen Aliquippa, had taken their people to Wills Creek. Outnumbered and with supplies running low, Washington surrendered the fort, later blaming Captains George Croghan and Andrew Montour for "involving the country in great calamity".

Tanacharison was "one of the sachems who had confirmed Croghan in his land grant of 1749" (Wainwright, 49), 200,000 acres minus about two square miles at the Forks of the Ohio for a British Fort. Thomas Penn and Pennsylvania planned to build a stone fort, but Croghan realized that his deeds would be invalid if in Pennsylvania and had Andrew Montour testify before the Assembly in 1751 that the Indians did not want the fort, that it was all Croghan's idea, scuttling the project.

In 1752 Croghan was on the Indian council that granted Virginia's Ohio Company permission to build the fort. Tanacharison's introduction of Croghan to the Virginia commissioners is further evidence that Croghan organized and led the 1748 Ohio Indian Confederation that Pennsylvania recognized as independent of the Six Nations and appointed Croghan as the colony's representative in negotiations.

Brethren, it is a great while since our brother, the Buck (meaning Mr. George Croghan)has been doing business between us, & our brother of Pennsylvania, but we understand he does not intend to do any more, so I now inform you that he is approv'd of by our Council at Onondago, for we sent to them to let them know how he has helped us in our councils here and to let you & him know that he is one of our people and shall help us still & be one of our council, I deliver him this string of wampum.

The Ohio Company fort was surrendered to the French by Croghan's half-brother, Edward Ward, and commanded by his business partner, William Trent, but Croghan's central role in these events remains suppressed, as he himself was in 1777, when Pittsburgh's president judge, Committee of Safety chairman, and person keeping the Ohio Indians pacificed since Pontiac's Rebellion was declared a traitor by General Edward Hand and exiled from the frontier.

It was to Croghan's Aughwick plantation that Tanacharison and Queen Aliquippa took their people in 1754 where the old queen died and Tanacharison became seriously ill and was taken to John Harris.

Tanacharison moved his people east to the Aughwick Valley near present Shirleysburg, Pennsylvania. He would take no active part in the remainder of the war. He died of pneumonia on October 4, 1754 on the farm of John Harris at Paxtang, Pennsylvania (near present-day Harrisburg, Pennsylvania).

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tanachar... )

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_o...

http://www.shmoop.com/french-indian-w...

http://www.helium.com/items/1130288-c...

http://burnpit.legion.org/2010/05/bat...

http://www.offthebeatenpath.ws/Battle...

http://suite101.com/article/the-battl...

by Walter R. Borneman (no photo)

by Walter R. Borneman (no photo) by Fred Anderson (no photo)

by Fred Anderson (no photo) by William M. Fowler Jr. (no photo)

by William M. Fowler Jr. (no photo) by Ruth Sheppard (no photo)

by Ruth Sheppard (no photo) by Jesse Russell (no photo)

by Jesse Russell (no photo) by Neville B. Craig (no photo)

by Neville B. Craig (no photo)

William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray was born in Calcutta, India, in 1811, to parents both of Anglo-Indian descent. Upon his father's death Thackeray went to England to live at age five. He attended several boarding schools, which experiences (including exceedingly dry lessons and canings) later provided material for Thackeray's writing. They also led him to find escape by reading the popular fiction of the day, including Sir Walter Scott and Pierce Egan. He entered Cambridge University in 1819. Not an outstanding student, he survived only two years of an inaccessible mentor and a preference for wine parties and gambling before he left.

Deciding his best route to an education was through extensive reading and educational travel, Thackeray set out for continental Europe. He led the dissipated lifestyle of a young gentleman even after losing much of his inheritance. But he began to supplement his income by contributing to newspapers, often about his travels. Then in Paris he met and married Isabella Shawe in 1836. Determined to support his family, Thackeray began writing in earnest. He published literary and art criticism, general articles, essays, travel books, and fiction, usually under a comic pseudonym.

Thackeray's travel writing frequently took him away from home, and when at home he often went to the quiet of men's clubs to work. Thus he missed the early signs of his wife's growing illness and depression. But after the birth of their third child, Isabella became almost completely withdrawn. Thackeray began searching for a cure, taking his wife to various doctors and health spas, all to no avail. She eventually went insane.

In the meantime, Thackeray still needed to write to support his wife and two surviving daughters. It is believed that his wife's illness began Thackeray's lifelong study of the situation of women in Victorian England, and his creating the memorable and believable female characters that appear in his masterpieces, Vanity Fair (1847), The History of Henry Esmond, Esq. (1852), and others. With his growing success, critics began to compare him to authors such as Charles Dickens. Thackeray enjoyed literary relationships with several authors and editors, including Dickens. The two men often had minor literary disagreements and still remained friends, until a breach that lasted years caused by Thackeray's publicly letting slip information about Dickens' mistress. This was healed only a few months prior to Thackeray's death, when Dickens and Thackeray met by chance in the street and shook hands.

Thackeray also produced numerous magazine publications, for a five-year period publishing an average of 59 articles per year in addition to working on his novels. Part of Thackeray's creative process included interaction with people: talk was a "necessary ingredient" of his research. He continued to travel and to visit and work with friends. He contributed numerous critiques on the writings of his contemporaries, including Dickens and Edward Bulwer Lytton. An artist as well as an author, Thackeray's lifetime output was so great that to this day no comprehensive bibliography of his publications has been compiled. Toward the end of his life he noted that his writing had earned him back his wealth, and he was proud that he could leave his daughters an inheritance. He died of a stroke in 1863, and an estimated 2000 people attended his funeral.

(Source: http://lib.byu.edu/exhibits/literaryw...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_...

http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/w...

http://www.online-literature.com/thac...

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...

http://www.wmthackeray.com/chronology...

http://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature...

http://www.biography.com/people/willi...

http://www.gradesaver.com/author/will...

(no image) William Makepeace Thackeray: A Literary Life by Peter L. Shillingsburg (no photo)

by Catherine Peters (no photo)

by Catherine Peters (no photo)

by

by

D.J. Taylor

D.J. Taylor

by Lewis Melville (no photo)

by Lewis Melville (no photo)

by Herman Merivale (no photo)

by Herman Merivale (no photo)

by John Camden Hotten (no photo)

by John Camden Hotten (no photo)

by

by

William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray was born in Calcutta, India, in 1811, to parents both of Anglo-Indian descent. Upon his father's death Thackeray went to England to live at age five. He attended several boarding schools, which experiences (including exceedingly dry lessons and canings) later provided material for Thackeray's writing. They also led him to find escape by reading the popular fiction of the day, including Sir Walter Scott and Pierce Egan. He entered Cambridge University in 1819. Not an outstanding student, he survived only two years of an inaccessible mentor and a preference for wine parties and gambling before he left.

Deciding his best route to an education was through extensive reading and educational travel, Thackeray set out for continental Europe. He led the dissipated lifestyle of a young gentleman even after losing much of his inheritance. But he began to supplement his income by contributing to newspapers, often about his travels. Then in Paris he met and married Isabella Shawe in 1836. Determined to support his family, Thackeray began writing in earnest. He published literary and art criticism, general articles, essays, travel books, and fiction, usually under a comic pseudonym.

Thackeray's travel writing frequently took him away from home, and when at home he often went to the quiet of men's clubs to work. Thus he missed the early signs of his wife's growing illness and depression. But after the birth of their third child, Isabella became almost completely withdrawn. Thackeray began searching for a cure, taking his wife to various doctors and health spas, all to no avail. She eventually went insane.

In the meantime, Thackeray still needed to write to support his wife and two surviving daughters. It is believed that his wife's illness began Thackeray's lifelong study of the situation of women in Victorian England, and his creating the memorable and believable female characters that appear in his masterpieces, Vanity Fair (1847), The History of Henry Esmond, Esq. (1852), and others. With his growing success, critics began to compare him to authors such as Charles Dickens. Thackeray enjoyed literary relationships with several authors and editors, including Dickens. The two men often had minor literary disagreements and still remained friends, until a breach that lasted years caused by Thackeray's publicly letting slip information about Dickens' mistress. This was healed only a few months prior to Thackeray's death, when Dickens and Thackeray met by chance in the street and shook hands.

Thackeray also produced numerous magazine publications, for a five-year period publishing an average of 59 articles per year in addition to working on his novels. Part of Thackeray's creative process included interaction with people: talk was a "necessary ingredient" of his research. He continued to travel and to visit and work with friends. He contributed numerous critiques on the writings of his contemporaries, including Dickens and Edward Bulwer Lytton. An artist as well as an author, Thackeray's lifetime output was so great that to this day no comprehensive bibliography of his publications has been compiled. Toward the end of his life he noted that his writing had earned him back his wealth, and he was proud that he could leave his daughters an inheritance. He died of a stroke in 1863, and an estimated 2000 people attended his funeral.

(Source: http://lib.byu.edu/exhibits/literaryw...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_...

http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/w...

http://www.online-literature.com/thac...

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...

http://www.wmthackeray.com/chronology...

http://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature...

http://www.biography.com/people/willi...

http://www.gradesaver.com/author/will...

(no image) William Makepeace Thackeray: A Literary Life by Peter L. Shillingsburg (no photo)

by Catherine Peters (no photo)

by Catherine Peters (no photo) by

by

D.J. Taylor

D.J. Taylor by Lewis Melville (no photo)

by Lewis Melville (no photo) by Herman Merivale (no photo)

by Herman Merivale (no photo) by John Camden Hotten (no photo)

by John Camden Hotten (no photo)

by

by

William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray

message 7:

by

Jerome, Assisting Moderator - Upcoming Books and Releases

(last edited May 04, 2020 03:11AM)

(new)

-

added it

Continental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in their revolt against the rule of Great Britain. The Continental Army was supplemented by local militias and other troops that remained under control of the individual states. General George Washington was the commander-in-chief of the army throughout the war.

Most of the Continental Army was disbanded in 1783 after the Treaty of Paris ended the war. The 1st and 2nd Regiments went on to form the nucleus of the Legion of the United States in 1792 under General Anthony Wayne. This became the foundation of the United States Army in 1796.

The Continental Army consisted of troops from all 13 colonies, and after 1776, from all 13 states. When the American Revolutionary War began at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the colonial revolutionaries did not have an army. Previously, each colony had relied upon the militia, made up of part-time citizen-soldiers, for local defense, or the raising of temporary "provincial regiments" during specific crises such as the French and Indian War. As tensions with Great Britain increased in the years leading up to the war, colonists began to reform their militia in preparation for the potential conflict. Training of militiamen increased after the passage of the Intolerable Acts in 1774. Colonists such as Richard Henry Lee proposed creating a national militia force, but the First Continental Congress rejected the idea.

The minimum enlistment age was 16 years of age, or 15 with parental consent.

On April 23, 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress authorized the raising of a colonial army consisting of 26 company regiments, followed shortly by similar but smaller forces raised by New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. On June 14, 1775, the Second Continental Congress decided to proceed with the establishment of a Continental Army for purposes of common defense, adopting the forces already in place outside Boston (22,000 troops) and New York (5,000). It also raised the first ten companies of Continental troops on a one-year enlistment, riflemen from Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware and Virginia to be used as light infantry, who later became the 1st Continental Regiment in 1776. On June 15, the Congress elected George Washington as Commander-in-Chief by unanimous vote. He accepted and served throughout the war without any compensation except for reimbursement of expenses.

Four major-generals (Artemas Ward, Charles Lee, Philip Schuyler, and Israel Putnam) and eight brigadier-generals (Seth Pomeroy, Richard Montgomery, David Wooster, William Heath, Joseph Spencer, John Thomas, John Sullivan, and Nathanael Greene) were appointed in the course of a few days. Pomeroy declined and the position was left unfilled.

General George Washington was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army on June 15, 1775. As the Continental Congress increasingly adopted the responsibilities and posture of a legislature for a sovereign state, the role of the Continental Army was the subject of considerable debate. There was a general aversion to maintaining a standing army among the Americans; but, on the other hand, the requirements of the war against the British required the discipline and organization of a modern military. As a result, the army went through several distinct phases, characterized by official dissolution and reorganization of units.

Soldiers in the Continental Army were citizens who had volunteered to serve in the army (but were paid), and at various times during the war, standard enlistment periods lasted from one to three years. Early in the war, the enlistment periods were short, as the Continental Congress feared the possibility of the Continental Army evolving into a permanent army. The army never reached over 17,000 men. Turnover was a constant problem, particularly in the winter of 1776-77, and longer enlistments were approved. Broadly speaking, Continental forces consisted of several successive armies, or establishments:

In addition to the Continental Army regulars, local militia units, raised and funded by individual colonies/states, participated in battles throughout the war. Sometimes, the militia units operated independently of the Continental Army, but often local militias were called out to support and augment the Continental Army regulars during campaigns. (The militia troops developed a reputation for being prone to premature retreats, a fact that was integrated into the strategy at the Battle of Cowpens.)

The financial responsibility for providing pay, food, shelter, clothing, arms, and other equipment to specific units was assigned to states as part of the establishment of these units. States differed in how well they lived up these obligations. There were constant funding issues and morale problems as the war continued. This led to the army offering low pay, often rotten food, hard work, cold, heat, poor clothing and shelter, harsh discipline, and a high chance of becoming a casualty.

At the time of the Siege of Boston, the Continental Army at Cambridge, Massachusetts, in June 1775, is estimated to have numbered from 14-16,000 men from New England (though the actual number may have been as low as 11,000 because of desertions). Until Washington's arrival, it remained under the command of Artemas Ward, while John Thomas acted as executive officer and Richard Gridley commanded the artillery corps and was chief engineer.

The British force in Boston was increasing by fresh arrivals. It numbered then about 10,000 men. Major Generals Howe, Clinton, and Burgoyne, had arrived late in May and joined General Gage in forming and executing plans for dispersing the rebels. Feeling strong with these veteran officers and soldiers around him—and the presence of several ships-of-war under Admiral Graves—the governor issued a proclamation, declaring martial law, branding the entire Continental Army and supporters as "rebels" and "parricides of the Constitution." Amnesty was offered to those who gave up their allegiance to the Continental Army and Congress in favor of the British authorities, though Samuel Adams and John Hancock were still wanted for high treason. This proclamation only served to strengthen the resolve of the Congress and Army.

After the British evacuation of Boston (prompted by the placement of Continental artillery overlooking the city in March 1776), the Continental Army relocated to New York. For the next five years, the main bodies of the Continental and British armies campaigned against one another in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. These campaigns included the notable battles of Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown, and Morristown, among many others.

The Continental Army was racially integrated, a condition the United States Army would not see again until the Korean War. African American slaves were promised freedom in exchange for military service in New England, and made up one fifth of the Northern Continental Army.

Throughout its existence, the Army was troubled by poor logistics, inadequate training, short-term enlistments, interstate rivalries, and Congress's inability to compel the states to provide food, money or supplies. In the beginning, soldiers enlisted for a year, largely motivated by patriotism; but as the war dragged on, bounties and other incentives became more commonplace. Two major mutinies late in the war drastically diminished the reliability of two of the main units, and there were constant discipline problems.

The army increased its effectiveness and success rate through a series of trials and errors, often at great human cost. General Washington and other distinguished officers were instrumental leaders in preserving unity, learning and adapting, and ensuring discipline throughout the eight years of war. In the winter of 1777-1778, with the addition of Baron von Steuben, of Prussian origin, the training and discipline of the Continental Army began to vastly improve. (This was the infamous winter at Valley Forge.) Washington always viewed the Army as a temporary measure and strove to maintain civilian control of the military, as did the Continental Congress, though there were minor disagreements about how this was carried out.

Near the end of the war, the Continental Army was augmented by a French expeditionary force (under General Rochambeau) and a squadron of the French navy (under the Comte de Barras), and in the late summer of 1781 the main body of the army travelled south to Virginia to rendezvous with the French West Indies fleet under Admiral Comte de Grasse. This resulted in the Siege of Yorktown, the decisive Battle of the Chesapeake, and the surrender of the British southern army. This essentially marked the end of the land war in America, although the Continental Army returned to blockade the British northern army in New York until the peace treaty went into effect two years later, and battles took place elsewhere between British forces and those of France and its allies.

A small residual force remained at West Point and some frontier outposts until Congress created the United States Army by their resolution of June 3, 1784.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continen...)

More:

http://www.history.army.mil/books/Rev...

http://www.mountvernon.org/educationa...

http://www.sonofthesouth.net/revoluti...

http://www.masshist.org/revolution/wa...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continen...

http://www.army.mil/article/40819/

http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h399...

http://www.history.army.mil/books/Rev...

http://www.ushistory.org/valleyforge/...

http://www.usahistory.info/Revolution...

(no image) Rag, Tag and Bobtail The Story of the Continental Army 1775 - 1783 by Lynn Montross (no photo)

by E. Wayne Carp (no photo)

by E. Wayne Carp (no photo)

by Charles Neimeyer (no photo)

by Charles Neimeyer (no photo)

by Charles Royster (no photo)

by Charles Royster (no photo)

by

by

Edward G. Lengel

Edward G. Lengel

by James Kirby Martin (no photo)

by James Kirby Martin (no photo)

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in their revolt against the rule of Great Britain. The Continental Army was supplemented by local militias and other troops that remained under control of the individual states. General George Washington was the commander-in-chief of the army throughout the war.

Most of the Continental Army was disbanded in 1783 after the Treaty of Paris ended the war. The 1st and 2nd Regiments went on to form the nucleus of the Legion of the United States in 1792 under General Anthony Wayne. This became the foundation of the United States Army in 1796.

The Continental Army consisted of troops from all 13 colonies, and after 1776, from all 13 states. When the American Revolutionary War began at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the colonial revolutionaries did not have an army. Previously, each colony had relied upon the militia, made up of part-time citizen-soldiers, for local defense, or the raising of temporary "provincial regiments" during specific crises such as the French and Indian War. As tensions with Great Britain increased in the years leading up to the war, colonists began to reform their militia in preparation for the potential conflict. Training of militiamen increased after the passage of the Intolerable Acts in 1774. Colonists such as Richard Henry Lee proposed creating a national militia force, but the First Continental Congress rejected the idea.

The minimum enlistment age was 16 years of age, or 15 with parental consent.

On April 23, 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress authorized the raising of a colonial army consisting of 26 company regiments, followed shortly by similar but smaller forces raised by New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. On June 14, 1775, the Second Continental Congress decided to proceed with the establishment of a Continental Army for purposes of common defense, adopting the forces already in place outside Boston (22,000 troops) and New York (5,000). It also raised the first ten companies of Continental troops on a one-year enlistment, riflemen from Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware and Virginia to be used as light infantry, who later became the 1st Continental Regiment in 1776. On June 15, the Congress elected George Washington as Commander-in-Chief by unanimous vote. He accepted and served throughout the war without any compensation except for reimbursement of expenses.

Four major-generals (Artemas Ward, Charles Lee, Philip Schuyler, and Israel Putnam) and eight brigadier-generals (Seth Pomeroy, Richard Montgomery, David Wooster, William Heath, Joseph Spencer, John Thomas, John Sullivan, and Nathanael Greene) were appointed in the course of a few days. Pomeroy declined and the position was left unfilled.

General George Washington was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army on June 15, 1775. As the Continental Congress increasingly adopted the responsibilities and posture of a legislature for a sovereign state, the role of the Continental Army was the subject of considerable debate. There was a general aversion to maintaining a standing army among the Americans; but, on the other hand, the requirements of the war against the British required the discipline and organization of a modern military. As a result, the army went through several distinct phases, characterized by official dissolution and reorganization of units.

Soldiers in the Continental Army were citizens who had volunteered to serve in the army (but were paid), and at various times during the war, standard enlistment periods lasted from one to three years. Early in the war, the enlistment periods were short, as the Continental Congress feared the possibility of the Continental Army evolving into a permanent army. The army never reached over 17,000 men. Turnover was a constant problem, particularly in the winter of 1776-77, and longer enlistments were approved. Broadly speaking, Continental forces consisted of several successive armies, or establishments:

In addition to the Continental Army regulars, local militia units, raised and funded by individual colonies/states, participated in battles throughout the war. Sometimes, the militia units operated independently of the Continental Army, but often local militias were called out to support and augment the Continental Army regulars during campaigns. (The militia troops developed a reputation for being prone to premature retreats, a fact that was integrated into the strategy at the Battle of Cowpens.)

The financial responsibility for providing pay, food, shelter, clothing, arms, and other equipment to specific units was assigned to states as part of the establishment of these units. States differed in how well they lived up these obligations. There were constant funding issues and morale problems as the war continued. This led to the army offering low pay, often rotten food, hard work, cold, heat, poor clothing and shelter, harsh discipline, and a high chance of becoming a casualty.

At the time of the Siege of Boston, the Continental Army at Cambridge, Massachusetts, in June 1775, is estimated to have numbered from 14-16,000 men from New England (though the actual number may have been as low as 11,000 because of desertions). Until Washington's arrival, it remained under the command of Artemas Ward, while John Thomas acted as executive officer and Richard Gridley commanded the artillery corps and was chief engineer.

The British force in Boston was increasing by fresh arrivals. It numbered then about 10,000 men. Major Generals Howe, Clinton, and Burgoyne, had arrived late in May and joined General Gage in forming and executing plans for dispersing the rebels. Feeling strong with these veteran officers and soldiers around him—and the presence of several ships-of-war under Admiral Graves—the governor issued a proclamation, declaring martial law, branding the entire Continental Army and supporters as "rebels" and "parricides of the Constitution." Amnesty was offered to those who gave up their allegiance to the Continental Army and Congress in favor of the British authorities, though Samuel Adams and John Hancock were still wanted for high treason. This proclamation only served to strengthen the resolve of the Congress and Army.

After the British evacuation of Boston (prompted by the placement of Continental artillery overlooking the city in March 1776), the Continental Army relocated to New York. For the next five years, the main bodies of the Continental and British armies campaigned against one another in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. These campaigns included the notable battles of Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown, and Morristown, among many others.

The Continental Army was racially integrated, a condition the United States Army would not see again until the Korean War. African American slaves were promised freedom in exchange for military service in New England, and made up one fifth of the Northern Continental Army.

Throughout its existence, the Army was troubled by poor logistics, inadequate training, short-term enlistments, interstate rivalries, and Congress's inability to compel the states to provide food, money or supplies. In the beginning, soldiers enlisted for a year, largely motivated by patriotism; but as the war dragged on, bounties and other incentives became more commonplace. Two major mutinies late in the war drastically diminished the reliability of two of the main units, and there were constant discipline problems.

The army increased its effectiveness and success rate through a series of trials and errors, often at great human cost. General Washington and other distinguished officers were instrumental leaders in preserving unity, learning and adapting, and ensuring discipline throughout the eight years of war. In the winter of 1777-1778, with the addition of Baron von Steuben, of Prussian origin, the training and discipline of the Continental Army began to vastly improve. (This was the infamous winter at Valley Forge.) Washington always viewed the Army as a temporary measure and strove to maintain civilian control of the military, as did the Continental Congress, though there were minor disagreements about how this was carried out.

Near the end of the war, the Continental Army was augmented by a French expeditionary force (under General Rochambeau) and a squadron of the French navy (under the Comte de Barras), and in the late summer of 1781 the main body of the army travelled south to Virginia to rendezvous with the French West Indies fleet under Admiral Comte de Grasse. This resulted in the Siege of Yorktown, the decisive Battle of the Chesapeake, and the surrender of the British southern army. This essentially marked the end of the land war in America, although the Continental Army returned to blockade the British northern army in New York until the peace treaty went into effect two years later, and battles took place elsewhere between British forces and those of France and its allies.

A small residual force remained at West Point and some frontier outposts until Congress created the United States Army by their resolution of June 3, 1784.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continen...)

More:

http://www.history.army.mil/books/Rev...

http://www.mountvernon.org/educationa...

http://www.sonofthesouth.net/revoluti...

http://www.masshist.org/revolution/wa...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continen...

http://www.army.mil/article/40819/

http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h399...

http://www.history.army.mil/books/Rev...

http://www.ushistory.org/valleyforge/...

http://www.usahistory.info/Revolution...

(no image) Rag, Tag and Bobtail The Story of the Continental Army 1775 - 1783 by Lynn Montross (no photo)

by E. Wayne Carp (no photo)

by E. Wayne Carp (no photo) by Charles Neimeyer (no photo)

by Charles Neimeyer (no photo) by Charles Royster (no photo)

by Charles Royster (no photo) by

by

Edward G. Lengel

Edward G. Lengel by James Kirby Martin (no photo)

by James Kirby Martin (no photo)

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton

Hamilton was born in 1757 on the island of Nevis, in the Leeward group, British West Indies. He was the illegitimate son of a common-law marriage between a poor itinerant Scottish merchant of aristocratic descent and an English-French Huguenot mother who was a planter's daughter. In 1766, after the father had moved his family elsewhere in the Leewards to St. Croix in the Danish (now United States) Virgin Islands, he returned to St. Kitts while his wife and two sons remained on St. Croix.

The mother, who opened a small store to make ends meet, and a Presbyterian clergyman provided Hamilton with a basic education, and he learned to speak fluent French. About the time of his mother's death in 1768, he became an apprentice clerk at Christiansted in a mercantile establishment, whose proprietor became one of his benefactors. Recognizing his ambition and superior intelligence, they raised a fund for his education.

In 1772, bearing letters of introduction, Hamilton traveled to New York City. Patrons he met there arranged for him to attend Barber's Academy at Elizabethtown (present Elizabeth), NJ. During this time, he met and stayed for a while at the home of William Livingston, who would one day be a fellow signer of the Constitution. Late the next year, 1773, Hamilton entered King's College (later Columbia College and University) in New York City, but the Revolution interrupted his studies.

Although not yet 20 years of age, in 1774-75 Hamilton wrote several widely read pro-Whig pamphlets. Right after the war broke out, he accepted an artillery captaincy and fought in the principal campaigns of 1776-77. In the latter year, winning the rank of lieutenant colonel, he joined the staff of General Washington as secretary and aide-de-camp and soon became his close confidant as well.

In 1780 Hamilton wed New Yorker Elizabeth Schuyler, whose family was rich and politically powerful; they were to have eight children. In 1781, after some disagreements with Washington, he took a command position under Lafayette in the Yorktown, VA, campaign (1781). He resigned his commission that November.

Hamilton then read law at Albany and quickly entered practice, but public service soon attracted him. He was elected to the Continental Congress in 1782-83. In the latter year, he established a law office in New York City. Because of his interest in strengthening the central government, he represented his state at the Annapolis Convention in 1786, where he urged the calling of the Constitutional Convention.

In 1787 Hamilton served in the legislature, which appointed him as a delegate to the convention. He played a surprisingly small part in the debates, apparently because he was frequently absent on legal business, his extreme nationalism put him at odds with most of the delegates, and he was frustrated by the conservative views of his two fellow delegates from New York. He did, however, sit on the Committee of Style, and he was the only one of the three delegates from his state who signed the finished document. Hamilton's part in New York's ratification the next year was substantial, though he felt the Constitution was deficient in many respects. Against determined opposition, he waged a strenuous and successful campaign, including collaboration with John Jay and James Madison in writing The Federalist. In 1787 Hamilton was again elected to the Continental Congress.

When the new government got under way in 1789, Hamilton won the position of Secretary of the Treasury. He began at once to place the nation's disorganized finances on a sound footing. In a series of reports (1790-91), he presented a program not only to stabilize national finances but also to shape the future of the country as a powerful, industrial nation. He proposed establishment of a national bank, funding of the national debt, assumption of state war debts, and the encouragement of manufacturing.

Hamilton's policies soon brought him into conflict with Jefferson and Madison. Their disputes with him over his pro-business economic program, sympathies for Great Britain, disdain for the common man, and opposition to the principles and excesses of the French revolution contributed to the formation of the first U.S. party system. It pitted Hamilton and the Federalists against Jefferson and Madison and the Democratic-Republicans.

During most of the Washington administration, Hamilton's views usually prevailed with the President, especially after 1793 when Jefferson left the government. In 1795 family and financial needs forced Hamilton to resign from the Treasury Department and resume his law practice in New York City. Except for a stint as inspector-general of the Army (1798-1800) during the undeclared war with France, he never again held public office.

While gaining stature in the law, Hamilton continued to exert a powerful impact on New York and national politics. Always an opponent of fellow-Federalist John Adams, he sought to prevent his election to the presidency in 1796. When that failed, he continued to use his influence secretly within Adams' cabinet. The bitterness between the two men became public knowledge in 1800 when Hamilton denounced Adams in a letter that was published through the efforts of the Democratic-Republicans.

In 1802 Hamilton and his family moved into The Grange, a country home he had built in a rural part of Manhattan not far north of New York City. But the expenses involved and investments in northern land speculations seriously strained his finances.

Meanwhile, when Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied in Presidential electoral votes in 1800, Hamilton threw valuable support to Jefferson. In 1804, when Burr sought the governorship of New York, Hamilton again managed to defeat him. That same year, Burr, taking offense at remarks he believed to have originated with Hamilton, challenged him to a duel, which took place at present Weehawken, NJ, on July 11. Mortally wounded, Hamilton died the next day. He was in his late forties at death. He was buried in Trinity Churchyard in New York City.

(Source: http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/char...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexande...

http://www.ushistory.org/brandywine/s...

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/hamilton/

http://www.treasury.gov/about/history...

http://www.alexanderhamiltonexhibitio...

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/...

by

by

Ron Chernow

Ron Chernow

by

by

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton by Richard Brookhiser (no photo)

by Richard Brookhiser (no photo) by Willard Sterne Randall (no photo)

by Willard Sterne Randall (no photo) by

by

Thomas J. Fleming

Thomas J. Fleming by

by

Forrest McDonald

Forrest McDonald by Stephen F. Knott (no photo)

by Stephen F. Knott (no photo) by Noble E. Cunningham Jr. (no photo)

by Noble E. Cunningham Jr. (no photo) by John Chester Miller (no photo)

by John Chester Miller (no photo)

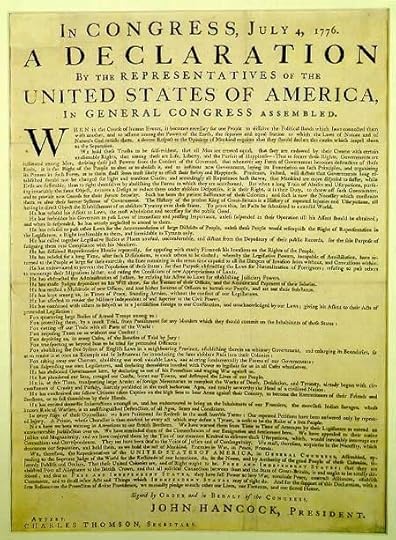

Continental Currency

Continental Currency

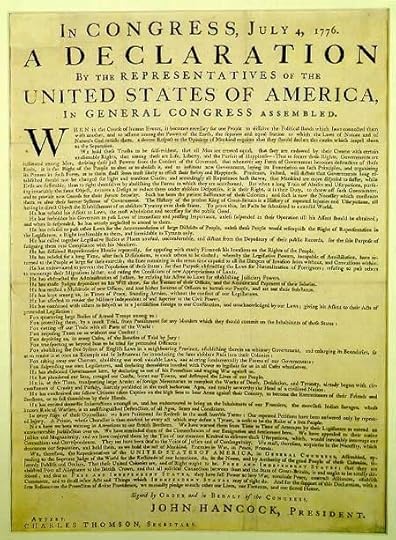

Early American currency went through several stages of development in the colonial and post-Revolutionary history of the United States. Because few coins were minted in the thirteen colonies that became the United States in 1776, foreign coins like the Spanish dollar were widely circulated. Colonial governments sometimes issued paper money to facilitate economic activity. The British Parliament passed Currency Acts in 1751, 1764, and 1773 that regulated colonial paper money.

During the American Revolution, the colonies became independent states; freed from British monetary regulations, they issued paper money to pay for military expenses. The Continental Congress also issued paper money during the Revolution, known as Continental currency, to fund the war effort. Both state and Continental currency depreciated rapidly, becoming practically worthless by the end of the war.

To address these and other problems, the United States Constitution, ratified in 1788, denied individual states the right to coin and print money. The First Bank of the United States, chartered in 1791, and the Coinage Act of 1792, began the era of a national American currency.

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_A...)

More:

http://www.frbsf.org/education/teache...

http://etext.virginia.edu/users/brock/

http://www.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3...

http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/mi...

http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/fl...

by Eric P. Newman (no photo)

by Eric P. Newman (no photo) by Robert E. Wright (no photo)

by Robert E. Wright (no photo) by Larry Allen (no photo)

by Larry Allen (no photo)(no image) The Currency Of The American Colonies, 1700 1764: A Study In Colonial Finance And Imperial Relations by Leslie V. Brock (no photo)

(no image) Money and Politics in America, 1755-1775 by Joseph Ernst (no photo)

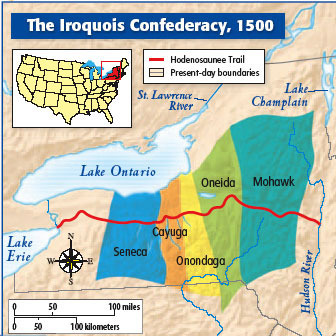

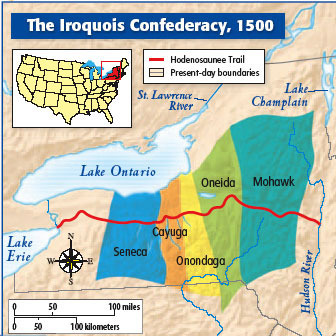

Iroquois Confederacy

Iroquois Confederacy, also called Iroquois League, Five Nations, or (from 1722) Six Nations, confederation of five (later six) Indian tribes across upper New York state that during the 17th and 18th centuries played a strategic role in the struggle between the French and British for mastery of North America. The five Iroquois nations, characterizing themselves as “the people of the longhouse,” were the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca. After the Tuscarora joined in 1722, the confederacy became known to the English as the Six Nations and was recognized as such at Albany, New York (1722).

Tradition credits the formation of the confederacy, between 1570 and 1600, to Dekanawidah, born a Huron, who is said to have persuaded Hiawatha, an Onondaga living among Mohawks, to abandon cannibalism and advance “peace, civil authority, righteousness, and the great law” as sanctions for confederation. Cemented mainly by their desire to stand together against invasion, the tribes united in a common council composed of clan and village chiefs; each tribe had one vote, and unanimity was required for decisions. The joint jurisdiction of 50 peace chiefs, known as sachems, embraced all civil affairs at the intertribal level.

The Iroquois Confederacy differed from other American Indian confederacies in the northeastern woodlands primarily in being better organized, more consciously defined, and more effective. The Iroquois used elaborately ritualized systems for choosing leaders and making important decisions. They persuaded colonial governments to use these rituals in their joint negotiations, and they fostered a tradition of political sagacity based on ceremonial sanction rather than on the occasional outstanding individual leader. Because the league lacked administrative control, the nations did not always act in unison; but spectacular successes in warfare compensated for this and were possible because of security at home.

During the formative period of the confederacy about 1600, the Five Nations remained concentrated in what is now central and upper New York state, barely holding their own with the neighbouring Huron and Mohican (Mahican), who were supplied with guns through their trade with the Dutch. By 1628, however, the Mohawk had emerged from their secluded woodlands to defeat the Mohican and lay the Hudson River valley tribes and New England tribes under tribute for goods and wampum. The Mohawk traded beaver pelts to the English and Dutch in exchange for firearms, and the resulting depletion of local beaver populations drove the confederacy members to wage war against far-flung tribal enemies in order to procure more supplies of beaver. In the years from 1648 to 1656, the confederacy turned west and dispersed the Huron, Tionontati, Neutral, and Erie tribes. The Andaste succumbed to the confederacy in 1675, and then various eastern Siouan allies of the Andaste were attacked. By the 1750s most of the tribes of the Piedmont had been subdued, incorporated, or destroyed by the league.

The Iroquois also came into conflict with the French in the later 17th century. The French were allies of their enemies, the Algonquins and Hurons, and after the Iroquois had destroyed the Huron confederacy in 1648–50, they launched devastating raids on New France for the next decade and a half. They were then temporarily checked by successive French expeditions against them in 1666 and 1687, but, after the latter attack, led by the marquis de Denonville, the Iroquois once again carried the fight into the heart of French territory, wiping out Lachine, near Montreal, in 1689. These wars were finally ended by a series of successful campaigns by New France’s governor, the comte de Frontenac, against the Iroquois in 1693–96.