The Pickwick Club discussion

In which Oliver Twist is covered

>

May 15-21 Chapters the Sixteenth through the Twenty-Second

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Another passage that strikes me as bewildering is this:

Another passage that strikes me as bewildering is this:"It seemed just the night when it befitted such a being as the Jew to be abroad. As he glided stealthily along, creeping beneath the shelter of the walls and doorways, the hideous old man seemed like some loathsome reptile, engendered in the slime and darkness through which he moved: crawling forth, by night, in search of some rich offal for a meal." Chapter 19, 3rd paragraph

If it were not for Dickens's horror at finding himself indicted of anti-Semitism by Eliza Davis, and his subsequent reaction of changing all references to Fagin's religion in the second part of the novel as well as how he dealt with Jewish people in Our Mutual Friend, this passage would surely leave a very bad taste in the reader's mouth. However, I think that this exaggeration in presenting Fagin might be put down to Oliver being a child and the omniscient narrator therefore, more or less, adopting the perspective of a child, who might invest very fierce adults with superhuman, demonic qualities.

Tristram wrote: "Another passage that strikes me as bewildering is this:

Tristram wrote: "Another passage that strikes me as bewildering is this:"It seemed just the night when it befitted such a being as the Jew to be abroad. As he glided stealthily along, creeping beneath the shelter..."

I thought it was referring to the serpent in the Garden of Evil -- the representation of evil manipulation of innocence.

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Another passage that strikes me as bewildering is this:

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Another passage that strikes me as bewildering is this:"It seemed just the night when it befitted such a being as the Jew to be abroad. As he glided stealthily along, creeping be..."

You have a point in saying that - as the imagery definitely conjures up ideas of a Serpent, and we have seen many other passages where Dickens represents Fagin as Satan, which is logical if we consider that Fagin tempts young people into crime and prostitution. Seeing the story as a kind of morality play might also be intended by Dickens's chosing the second title "The Parish Boy's Progress".

And yet, the dehumanizing language in the passage above goes against the grain.

That said, however, I want to underline that I do not imply that Dickens was an anti-Semite, given his sincere dismay at Jewish people feeling offended by his frequent use of the term "the Jew" in connection with Fagin. Plus, being more of a supporter of historism, esp. in literature, I endeavour to judge a book firstly in the context of its own time - if this is possible at all - and hardly expect a writer to suit tastes and susceptibilities of generations they could know nothing about.

The introduction to my copy says that "A Parish Boy's Progress" is an allusion to Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, most likely in a satirical sense, for whatever that's worth.

By the way, I'll catch up over the weekend. I'm sorry for the delay gentlemen.

By the way, I'll catch up over the weekend. I'm sorry for the delay gentlemen.

Tristram wrote: "That said, however, I want to underline that I do not imply that Dickens was an anti-Semite,"

Tristram wrote: "That said, however, I want to underline that I do not imply that Dickens was an anti-Semite,"No more than was prevalent in the culture of his time, but that culture was to a fairly meaningful degree anti-Semetic, and Dickens was not immune to the societal values. It wasn't, I think your point is, intentional anti-antisemitism, and I agree. But the general depiction of Jews in Victorian literature was negative, up to Eliot's Daniel Deronda, which was perhaps the first work of Victorian literature to present a major Jewish character in a positive and sympathetic light.

It is exactly what I meant, Everyman: Dickens, while being dyed in the hue of his times and thus not quite mirroring our quotidian views, was not intentionally anti-Semitic. In my copy, it actually says that Fagin was modelled on a notorious Jewish fence by the name of Ikey Solomon. Fagin's demonic qualities can, as I like to think, be attritbuted to the morality play character of the book, which is also in line with the woodcut characters in this novel.

It is exactly what I meant, Everyman: Dickens, while being dyed in the hue of his times and thus not quite mirroring our quotidian views, was not intentionally anti-Semitic. In my copy, it actually says that Fagin was modelled on a notorious Jewish fence by the name of Ikey Solomon. Fagin's demonic qualities can, as I like to think, be attritbuted to the morality play character of the book, which is also in line with the woodcut characters in this novel.19th century literature is often not very favourable of Jewish culture and people - and Daniel Deronda, which many consider Eliot's masterpiece, is a laudable exception. It is ages ago that I read that book, and I was in love with a mirthful and captivating temptress at that time, so I couldn't concentrate too much. Today, having been married for a decade, my powers of concentration are somewhat restored, and I might give the book another go.

I tried to come up with some of my own thoughts on anti-Judaism in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice in my review on that play, but otherwise I have hardly ever come across that topic in English literature. Dostoevsky, however, is quite another thing - it's unpleasant for me to have to admit that one of my most beloved writers must have been a downright anti-Semite, but then he also was anti-Polish and anti-German, which, of course, has to be seen in the context of his Slavo-phil(iac?) and extremely religious worldview.

Jonathan wrote: "The introduction to my copy says that "A Parish Boy's Progress" is an allusion to Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, most likely in a satirical sense, for whatever that's worth.

Jonathan wrote: "The introduction to my copy says that "A Parish Boy's Progress" is an allusion to Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, most likely in a satirical sense, for whatever that's worth. By the way, I'll catch u..."

It is probably satirical, and maybe only applied because it sounds so nice, because after all, both Bunyan and Dickens are highly moralistic in their respective tales. Furthermore I cannot spot any criticism Dickens might have made of what Bunyan said.

At this point I would also like to make a request to the majority of silent readers here: Why not contribute to the discussions? I'm sure when so many people read a classic like Oliver Twist there will be many things that come to people's minds, and it's fun not just to read a book but to exchange opionions and collect out-ot-the-way information on it. The more the merrier!

At this point I would also like to make a request to the majority of silent readers here: Why not contribute to the discussions? I'm sure when so many people read a classic like Oliver Twist there will be many things that come to people's minds, and it's fun not just to read a book but to exchange opionions and collect out-ot-the-way information on it. The more the merrier!

Tristram wrote: "It is ages ago that I read that book, and I was in love with a mirthful and captivating temptress at that time, so I couldn't concentrate too much. "

Tristram wrote: "It is ages ago that I read that book, and I was in love with a mirthful and captivating temptress at that time, so I couldn't concentrate too much. "LOL!

Does anybody else think that Oliver is a wimp for letting himself be taken off the street that way? Why didn't he yell for a policeman? Make more of a fuss? I know he was just a boy against two adults, but still.

Does anybody else think that Oliver is a wimp for letting himself be taken off the street that way? Why didn't he yell for a policeman? Make more of a fuss? I know he was just a boy against two adults, but still.

Everyman wrote: "Does anybody else think that Oliver is a wimp for letting himself be taken off the street that way? Why didn't he yell for a policeman? Make more of a fuss? I know he was just a boy against two ..."

Everyman wrote: "Does anybody else think that Oliver is a wimp for letting himself be taken off the street that way? Why didn't he yell for a policeman? Make more of a fuss? I know he was just a boy against two ..."Dickens would probably have argued that Oliver could not have raised hue and cry against his captors and yelled for a policman because after all, he ran away as a parish boy from the workhouse and his being found by the police might have resulted in his return to Bumble and the likes.

But then you could argue that going back to the workhouse could not have been as horrible a thought to Oliver as going back to Fagin. Another counter-argument, even stronger than the first, is that Oliver has proved such a naive dunce throughout the novel - just think of his not realizing where all these handkerchiefs come from and what company he has fallen into - that he would hardly have reasoned in the way I did above.

So he probably is a wimp, but necessarily so because his wimpiness increases the menacing effect of Fagin and Sikes. That being said, however, all this makes it difficult for me as a reader to really care about Oliver since he is such a non-entity.

Tristram wrote: "That being said, however, all this makes it difficult for me as a reader to really care about Oliver since he is such a non-entity.

Tristram wrote: "That being said, however, all this makes it difficult for me as a reader to really care about Oliver since he is such a non-entity."

I understand what you mean, but I look on him sort of as a baby fawn beset by a pack of wolves, and I necessarily root for the fawn.

But he's a strange mix of helplessness and gumption. Running away to London at his age took real gumption. And surviving the workhouse without a totally warped personality says something good about him. But then there's all his wimpiness in other areas. He doesn't seem like a real person, and I'm not sure that Dickens meant us to take him as one. I suspect that Dickens cared less about him as a person in his own right and more as a character around which to rouse public anger against the treatment of poor children.

Everyman wrote: " He doesn't seem like a real person, and I'm not sure that Dickens meant us to take him as one. I suspect that Dickens cared less about him as a person in his own right and more as a character around which to rouse public anger against the treatment of poor children. "

Everyman wrote: " He doesn't seem like a real person, and I'm not sure that Dickens meant us to take him as one. I suspect that Dickens cared less about him as a person in his own right and more as a character around which to rouse public anger against the treatment of poor children. "I completely agree with you here, and would like to think of Oliver as a vehicle of criticism and of arousing emotions conducive to voicing this criticism. On the one hand, Oliver is a living indictment of the cruelty that was exerted on children under the Poor Law - as well as Little Dick, the boy who comes up with purple prose like this: "I heard the doctor tell them I was dying. [...] I know the doctor must be right, Oliver, because I dream so much of Heaven and Angels, and kind faces that I never see when I am awake." This is very moving, but hardly the way a 9-year-old would speak, is it? But probably Dickens knew, or thought, that a genteel public would hardly feel the same emotions if he had his starved children use regional English, drop their aitches and be less prolix. - So Oliver and his fellow-sufferers are hardly real persons, but vehicles of criticism.

You also said that there must be something good in Oliver because for all his childhood experiences he never gets warped. This brings us right into the midst of a problem Dickens has: The case of Oliver seems to imply that a noble person will behave nobly and decently in whatever situation and circumstances; a noble spirit cannot be spoiled. This intimation Dickens makes with the case of Oliver is also in line with his critcism of paupers in workhouses living in worse conditions that felons in prisons (in one of the earlier chapters).

On the other hand, what about Nancy - and other examples I keep mum about right now in order not to spill any beans? Nancy has become tainted by Fagin's "education", and yet there seems to be something good inside her. She seems to be making a case for the opposite idea, that good people can be warped by bad experiences and fall into vice.

I wonder if Dickens has noticed this contradiction.

Tristram wrote: "I wonder if Dickens has noticed this contradiction. "

Tristram wrote: "I wonder if Dickens has noticed this contradiction. "That's a really nice observation/question. I hadn't picked up on it, but you're right.

To carry the point maybe a bit further, Dickens has two so far) very poor but good at heart characters who both come into close contact with Fagin, but (so far) one remains pure and one gets corrupted.

I hope it isn't just a matter of gender, but of something else in their characters. Or maybe Dickens just needed these exemplars and isn't all that worried about psychological consistency.

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I wonder if Dickens has noticed this contradiction. "

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I wonder if Dickens has noticed this contradiction. "That's a really nice observation/question. I hadn't picked up on it, but you're right.

To carry the point maybe a bit furth..."

I have come across another passage that may be interesting in the context of our question, but as this aforesaid passage is not part of this week's pensum, not even in a Pickwickian sense, we will just have to bide our time to keep matters go in an orderly fashion.

Referring back, however, to how the Dodger is introduced, I was struck by Dickens mentioning the Dodger's having "little, sharp, ugly eyes", which reminds me of a German saying according to which the eyes are the window to the soul - I don't know if this is also a common saying in English - and which could be read as evidence of the Dodger's innate inclination to crime. This would, then, imply that Dickens believed in some people having an inclination towards crime already rooted in their characters - just think of Sikes and Fagin, who are evil through and through.

Yet another of Dickens's highly-unlikely-coincidences-as-major-plot-elements comes in Chapter 17 where Bumble just happens to bumble over the advertisement about Oliver. The idea that Bumble would read a newspaper in the first place, let alone this newspaper, seems very strained.

Yet another of Dickens's highly-unlikely-coincidences-as-major-plot-elements comes in Chapter 17 where Bumble just happens to bumble over the advertisement about Oliver. The idea that Bumble would read a newspaper in the first place, let alone this newspaper, seems very strained.

Everyman wrote: "Yet another of Dickens's highly-unlikely-coincidences-as-major-plot-elements comes in Chapter 17 where Bumble just happens to bumble over the advertisement about Oliver. The idea that Bumble would..."

Everyman wrote: "Yet another of Dickens's highly-unlikely-coincidences-as-major-plot-elements comes in Chapter 17 where Bumble just happens to bumble over the advertisement about Oliver. The idea that Bumble would..."Your are right: this is rather strained, but I had the feeling that Dickens wanted to keep Mr. Bumble in the story with a view to later events in which the beadle is going to be involved. I'm going to put my second observation in spoiler marks as I don't know if the event in question already fell into this week's pensum:

(view spoiler)

I am thoroughly enjoying these threads after rereading the relevant chapters, even though they are not strictly still "live"! What startled me with this one was that I had made a note of 2 quotations about Fagan - one to show his intentions and one as a rather highly-coloured (let's fact it, the whole novel is highly coloured and populist!) description of him. Imagine my surprise therefore, to see exactly the same two descriptions quoted by Tristram in comments one and two!

I am thoroughly enjoying these threads after rereading the relevant chapters, even though they are not strictly still "live"! What startled me with this one was that I had made a note of 2 quotations about Fagan - one to show his intentions and one as a rather highly-coloured (let's fact it, the whole novel is highly coloured and populist!) description of him. Imagine my surprise therefore, to see exactly the same two descriptions quoted by Tristram in comments one and two!I made lengthy comments on Fagin in the first thread, but there's one element which nobody here seems to have spotted.

Victorian society placed a lot of value and emphasis on industry, capitalism and individualism. And who embodies this most successfully? Fagin - who operates in the illicit businesses of theft and prostitution! His "philosphy" is that the group’s interests are best maintained if every individual looks out for himself, saying,

"a regard for number one holds us all together, and must do so, unless we would all go to pieces in company."

This is indeed heavy irony on Dickens's part, and adds to Fagan's multi-layered personality. As I remember, there are clues in the novel that he has his origins in circus folk from Eastern Europe. Apart from the long cloak and flamboyant charades though, I haven't picked up any info as to that yet.

There was a criticism that there was an inconsistency in Dickens's portrayal that (in Tristram's words) "a noble person will behave nobly and decently in whatever situation and circumstances; a noble spirit cannot be spoiled." This seemed to be agreed on. Nancy, however "seems to be making a case for the opposite idea, that good people can be warped by bad experiences and fall into vice." (Tristram again).

That is not an inconsistency in Dickens writing, it is what happens in Real Life (or if you will have it, good psychology)! Here's an example. I am a retired deputy head teacher. There have been many instances - generations sometimes - where I have seen siblings have virtually the same experiences in terms of their family and day-to-day events. Mostly their experiences have been fine and within "normal" limits, but others may have had to deal with heart-breaking events which would challenge an adult never mind a child, or emotional impoverishment, or cruelty...

The point is that there is a colossal variation between their reactions. I have been constantly surprised by how I can be dealing with a troubled damaged child one year, and then their sibling the next is as sunny-tempered as they come. People would say, "Oh - look at what they have to deal with" for the first one...so what explains the next? (This is obviously a rhetorical question.)

It would be so easy for an author to take a stereotypical view of children having early influences which then inform their later behaviour and ethics to such a ridiculous extent that they all behave the same way. Dickens can be guitly of "persuasive literary techniques" yes; he likes to tell us what to think. But he is too great an author to put his characters into straitjackets for this purpose. Diversity of characterisation is one of his great strengths. Look at the plethora of characters in The Pickwick Papers.

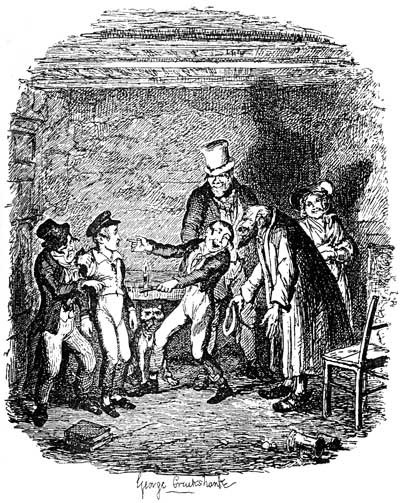

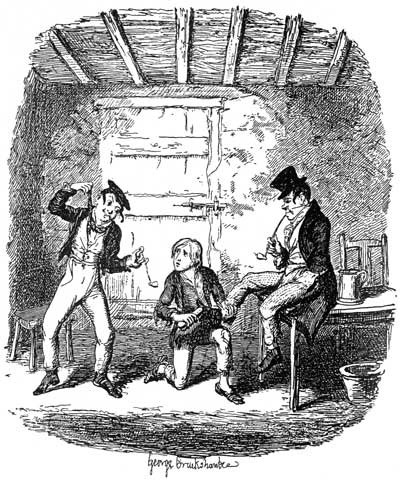

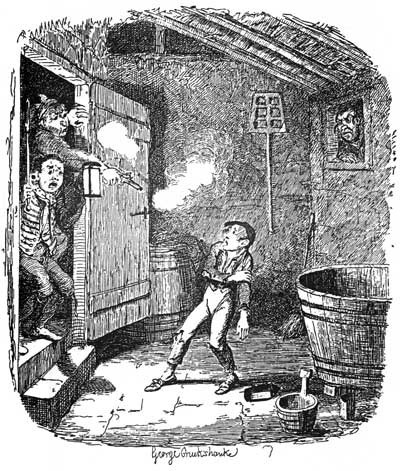

Thanks for the thoughts - and the original illustrations! On to the next chapters :)

What I find rather interesting here is that despite all the black-and-white-oppositions and sentimentality Oliver Twist may be guilty of Dickens gives us a rather realistic account of how Fagin tries to change Oliver's mindset and make him an obedient member of his gang, nameley by shutting him off completely from any form of social contact for quite a while. Cf. chapter 18, final paragraph:

It is quite astonishing that on the one hand Dickens prove so much insight into human nature and the ways of manipulating it, whereas on the other side, Oliver still remains so unaffected by this crafty procedure. Here Dickens defies realism with a vengeance, the only question being, why.