The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

The Liberation Trilogy Boxed Set

THE SECOND WORLD WAR

>

SECOND WORLD WAR - THE LIBERATION TRILOGY - GLOSSARY - PART TWO ~ (SPOILER THREAD)

St. John's Episcopal Church

St. John's Episcopal Church

Long known as "the Church of the Presidents," St. John's Episcopal Church has served virtually as the chapel to the White House for nearly two centuries. Every President since James Madison has worshiped here on some occasion. As far back as 1816, records show that a committee was formed to wait on the President of the United States and offer him a pew. James Madison chose pew 54 and insisted on paying the customary annual rental. The next five Presidents in succession--James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren and William Henry Harrison--occupied this pew during their terms of office. Since then, by tradition, pew 54 has been set aside for Presidents of the United States. There are other ways in which the church is further connected with Presidents. Many Presidents have been members of the church. James Madison's wife, Dolly, was baptized and confirmed here. Franklin D. Roosevelt paid homage to tradition by spending a few minutes in prayer here on his two inauguration days.

The church was built in 1816 by Benjamin Latrobe, the noted architect who worked on the Capitol and the White House, as well as the Decatur House. The original Classical style church was built in the form of a Greek Cross, where each arm was equal in length. Latrobe conceived of his churches as meeting houses, with open preaching space unencumbered by piers and columns. As a result, he insisted on simplicity in architecture and a pulpit centrally located so that all might see. St. John's size soon proved inadequate for the growing congregation. In 1820, workmen extended the west transept arm and fronted it with a Roman Doric portico, which resulted in a Latin Cross form.

Over time, further alterations, such as the triple-tiered steeple, significantly altered Latrobe's plan, but the original structure is still recognizable.

Having seen more than its share of national occasions as well as the roster of those who have worshiped in this church, its significance goes without saying. However, there are many notable treasures in the church such as the twenty-seven handsome memorial windows adorning the building. An 18th-century prayer book placed in the President's pew has been autographed by many of the Presidents. A silver chalice and a solid gold communion chalice, encrusted with jewels, are also among its treasures. St. John's is still a living parish in the heart of Washington, DC With its bright yellow stuccoed walls, and golden cupola and dome, St. John's is a lively ornament to Lafayette Square. The church stands as one of the few remaining original buildings left near Lafayette Park today.

(Source: http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/wash/dc2...)

More:

http://www.stjohns-dc.org/article/48/...

http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/l...

http://www.culturaltourismdc.org/thin...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bp0G7N...

http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/29...

by Richard F. Grimmett (no photo)

by Richard F. Grimmett (no photo) by

by

William Stevens Perry

William Stevens Perry  by Robert Benedetto (no photo)

by Robert Benedetto (no photo) by

by

Randi Minetor

Randi Minetor(no image) The Church on Lafayette Square: A History of St. John's Church, Washington, D.C., 1815-1970 by Constance McLaughlin Green (no photo)

Sandhurst

Sandhurst

The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in Surrey is where all Officers in the British Army are trained to take on the responsibilities of leading soldiers.

More than 80% of Officer Cadets are university graduates, but some arrive with A-Levels or equivalent. Others are serving soldiers who have been selected for Officer training and some come from overseas, having been chosen by their own armies to train at the world famous Academy. It is not possible for anyone to undertake training at their own private expense.

The Commissioning Course for Regular Army Officers is 48 weeks long, including recess periods. It runs three times a year, starting in January, May and September. The Territorial Army course is shorter, as is the training course Sandhurst offers for military personnel with professional qualifications in areas such as law and medicine.

Training at Sandhurst covers military, practical and academic subjects and while it is mentally and physically demanding, there's also plenty of time set aside for sport and adventurous training. It's a proud day for Officer Cadets going into the Regular Army when they finally march up the steps of Old College to be commissioned as Officers at the end of the prestigious Sovereign's Parade.

(Source: http://www.army.mod.uk/training_educa...)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_M...

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknew...

http://www.philipjohnston.com/rmas/hi...

http://worldhistoryproject.org/1893/9...

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknew...

http://www.famouswhy.com/List/c/Sandh...

http://www.sandhurstcollection.co.uk/

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/t...

http://www.nndb.com/edu/212/000110879/

by Angela Holdsworth (no photo)

by Angela Holdsworth (no photo) by A.F. Mockler-Ferryman (no photo)

by A.F. Mockler-Ferryman (no photo) by Sandhurst roy. military coll (no photo)

by Sandhurst roy. military coll (no photo)(no image) The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst: 250 Years by

David G. Chandler

David G. Chandler(no image) History Of Sandhurst by Kitty Dancy (no photo)

(no image) Sandhurst by Michael Yardley (no photo)

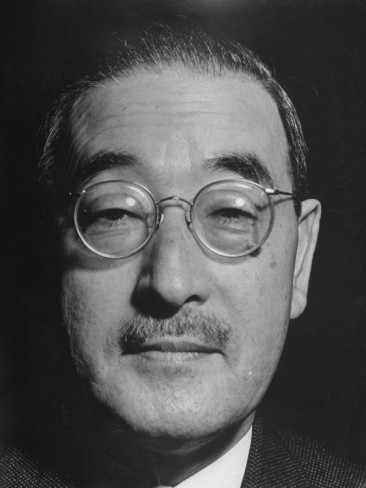

Walter C. Short

Walter C. Short

Walter Short was born on 30 March 1880 in Fillmore, Illinois. He was commissioned in 1901 and served with the American Expeditionary Force in France in World War I as a training officer. On 8 February 1941 he was promoted to lieutenant-general and given command of the Hawaiian Department of the US Army.

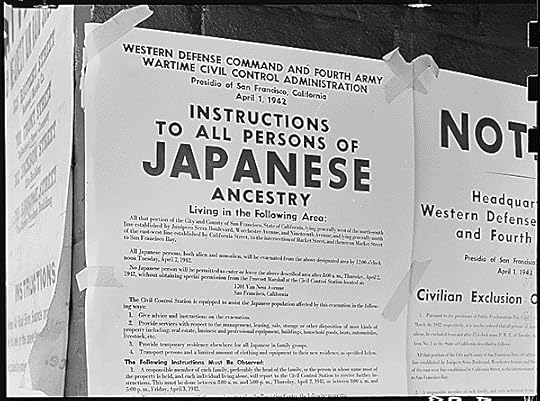

His relationship with the Navy and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel's (Kimmel, Husband E.) headquarters, CinCPAC, was cordial but not close. He felt secure from attack because of the Navy's presence while Kimmel was content that the Army would prevent air attack or invasion of the Hawaiian Islands. Short's chief concern was security against sabotage by the ethnic Japanese in Hawaii, the nisei. When he received a war warning from Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall (Marshall, George C.) on 27 November, he interpreted it in a limited fashion and set guards to watch over aircraft. This involved parking the planes in tight blocks, and thus making them excellent targets from the air.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor he was relieved of his command and reverted to the rank of major-general. He retired from the army in February 1942 and went to work for Ford in Dallas. An investigation into Pearl Harbor found him, with Kimmel, guilty of errors of judgement, but he never got the court martial he felt would vindicate him. He died on 3 September 1949.

(Source: http://ospreypearlharbor.com/encyclop...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_S...

http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/wcsh...

http://www.nationalgeographic.com/pea...

http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/S/h/Short...

http://www.ausa.org/publications/army...

by Charles Robert Anderson (no photo)

by Charles Robert Anderson (no photo) by Edward L. Beach, Jr. (no photo)

by Edward L. Beach, Jr. (no photo) by Frederic L. Borch (no photo)

by Frederic L. Borch (no photo) by Henry C., Clausen (no photo)

by Henry C., Clausen (no photo) by

by

Gordon W. Prange

Gordon W. Prange by Hilary Conroy (no photo)

by Hilary Conroy (no photo)

Margaret Daisy Suckley

Margaret Daisy Suckley

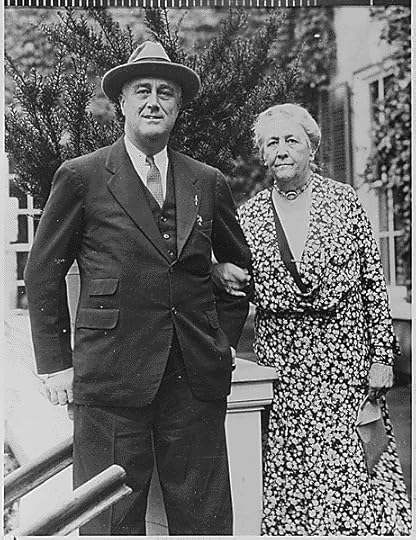

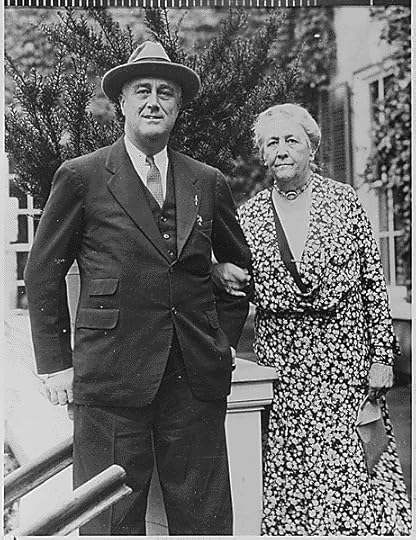

Margaret "Daisy" Suckley, a distant cousin who was also a friend and confidante to Franklin D. Roosevelt, was born in 1891 in Rhinebeck, New York. She gave Roosevelt his famous dog, Fala, and was with him in Warm Springs, Georgia, when he died. Daisy was also one of the first archivists at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum. She was responsible for managing the Library's large photograph collection, using her intimate knowledge of President Roosevelt's life to identify the people and places in the photos. Daisy lived in Rhinebeck, NY until her death in 1991, six months before her 100th birthday.

Margaret “Daisy” Suckley was born December 20, 1891 at her family home, Wilderstein, in Rhinebeck, New York. She was the fifth child and first daughter of her parents, Elizabeth Phillips Montgomery and Robert Bowne Suckley (rhymes with Book-ly). Both parents came from wealthy families. During Daisy’s childhood, her parents’ attempted to continue the lifestyle of a wealthy Hudson River family. In fact, Daisy’s father listed “gentleman” as his occupation on his passport.

The family divided their time between Wilderstein and a residence in Manhattan. However, Wilderstein was expensive to maintain. A period of economic instability forced the Suckleys to close Wilderstein and move to Switzerland, where they would live for the next ten years.

After their return, Daisy’s father wanted his daughter to attend college. She would attend Bryn Mawr College, but only for two years. Afterwards, she returned home to help her mother maintain the home and look after the many guests they were always entertaining. She still led a sheltered life, but World War I helped expand her horizons. She spent summers selling war bonds door-to-door in Rhinebeck and volunteered as a nurse’s aide at a hospital on Ellis Island during the winter. Daisy’s father died suddenly from a heart attack and the family’s fortune lay in the hands of her eccentric brother, Robert.

Following a series of bad investments coupled with the crash of 1929, much of the Suckley wealth was lost. Daisy’s sister, Elizabeth, also returned to Wilderstein with her husband and their three children, having suffered losses of their own. Daisy took a job with her aunt, Sophie Langdon, as a paid companion, and found herself the caretaker of Wilderstein and its inhabitants. She divided her time between Mrs. Langdon’s home in Manhattan and Rhinebeck, using her salary to support her family. By now, Daisy had resigned herself to a life taking care of her family. She accepted her duties, but longed for more.

The Suckleys and Roosevelts had always been friends, but Daisy and FDR’s close relationship began when she attended his 1933 inauguration. In the spring of 1922, Sara Delano Roosevelt invited Daisy to tea at Springwood. Sara told Daisy her son was lonely and she hoped a familiar face and some company would cheer him up. Franklin D. Roosevelt was in Hyde Park that spring recovering from a case of infantile paralysis, which left him paralyzed from the waist down. Daisy saw Franklin a few times that spring, keeping him company while he did his exercises and watching while he struggled to regain control of his legs. It wasn’t until Roosevelt’s 1933 Presidential Inauguration, however, that their real story began. Roosevelt invited Daisy to attend his inauguration that year and afterward a close friendship, one that would last the rest of Roosevelt’s life, began.

Daisy was quiet, unobtrusive, and overlooked by history, but she was also one of Roosevelt’s closest friends. After the 1933 inauguration, Daisy corresponded with Roosevelt regularly. He spoke with her about the presidency and she worried about his health. They also sent each other small gifts and shared secrets. In his letter dated September 23, 1935, Roosevelt writes to Daisy, “Do you know that you alone have known that I was a bit ‘cast down’ these past weeks. I couldn’t let anyone else know it – but somehow I seem to tell you all those things and what I don’t happen to tell you, you seem to know anyway!” Daisy saw Roosevelt almost every time he was in Hyde Park and even visited him in Washington, D. C. When in Hyde Park, Roosevelt would take Daisy for drives and they would explore the Hudson Valley together.

In 1939 the King and Queen of England paid an unprecidented personal visit to the US. They were invited by Roosevelt to Hyde Park where the Royal couple attended church services, took a driving tour with FDR, and enjoyed a hot dog picnic at Top Cottage. Suckley also attended many of those royal festivities and described the details in her diaries, now housed in archival collections at Wilderstein Preservation in Rhinebeck, NY.

On September 22, 1935, Daisy and FDR visited a hill in Dutchess County during one of their drives. Thereafter, Daisy and Roosevelt would affectionately refer to Dutchess Hill as “Our Hill.” They began to discuss plans for a cottage there (eventually Top Cottage would be built on this spot) and Daisy started to collect books for “Our Library.” Eventually, Roosevelt shifted his plans and instead of a cottage for the two of them to disappear to after retirement, he envisioned an escape from life as President. This is what it would eventually become, but Daisy always fondly remembered the time they spent on “Our Hill.”

As time progressed, their correspondence lost the flirtatious undertones, but the closeness remained. Roosevelt confided in Daisy, telling her about secret political meetings, such as the Atlantic Charter Conference. She still visited him in Washington and they continued to meet for tea and go for drives when he came to Hyde Park, but Daisy no longer believed they would be sharing the cottage on top of their hill after Roosevelt retired. Instead, she enjoyed his company, continued their correspondence and cherished the small comforts she could provide for him.

In 1940, Daisy presented President Roosevelt with his Scottie, Fala. A friend of Daisy’s had a litter of Scottie puppies and gave one to Daisy. She trained the puppy for six months before presenting him to President Roosevelt. Fala was Roosevelt’s constant companion for the next five years and is considered one of the most popular Presidential pets. After Roosevelt’s death, Daisy took Fala home with her, believing FDR wished her to care for him. However, after a visit from James Roosevelt (FDR’s son), she returned the dog to Eleanor Roosevelt, who would keep him for the rest of his life.

In September of 1941, FDR hired Daisy as an archivist at the new Franklin D. Roosevelt Library. In 1941, Daisy’s life changed again. Her aunt, Sophie Langdon, passed away on August 3. Daisy had been earning a living and supporting her family by acting as her aunt’s companion since the early thirties. Now, she was without a job and her family was without an income.

In September, Roosevelt gave Daisy a job at the new FDR Library in Hyde Park. She would work part time as a junior archivist, sorting Roosevelt’s personal and family papers, earning $1,000 a year. Not only did this solve Daisy’s financial problems, it gave them more opportunities to see each other regularly.

Daisy worked as an archivist at the FDR Library for 22 years. While Roosevelt was still alive, her job consisted of organizing his papers and books. FDR was constantly bringing new things up to the library – papers, books, and objects for the museum. The original library staff was responsible for organizing the material and arranging the museum. After Roosevelt’s death, the library continued organizing his material. Daisy even cataloged the entire contents of both the President's Study at the Library, and of Top Cottage, room by room, creating a master list of the objects and where they were placed. After FDR's death, Daisy no longer spent much time dealing with the manuscripts in the collection. Instead, she worked with the photographs, identifying subjects and creating a filing system. With Daisy’s help, thousands of photographs were cataloged.

Daisy was with President Roosevelt in Warm Springs, GA when he died on April 12, 1945. She was on the train that bore FDR’s body to Washington, D. C. and attended the burial at Hyde Park, NY. She returned to the library, continuing her work, until 1963. Daisy remained at Wilderstein, caring for her family until she was the only one left. In 1980, Wilderstein Preservation was formed to maintain the legacy of her Hudson River home.

She died in her home on June 29, 1991, her 100th year. The people in Roosevelt’s life never suspected Daisy of being exceptionally close to him and it wasn’t until after Daisy’s death that their close friendship was revealed. (Source: http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/abou...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret...

http://www.biography.com/people/marga...

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/07/tra...

http://www.flickr.com/photos/fdrlibra...

http://www.more.com/entertainment/cel...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franklin...

http://fdrsdeadlysecret.blogspot.com/...

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000...

http://www.hvmag.com/core/pagetools.p...

http://www.newyorksocialdiary.com/nod...

by

by

Geoffrey C. Ward

Geoffrey C. Ward by Cynthia Owen Philip (no photo)

by Cynthia Owen Philip (no photo) by

by

Elliott Roosevelt

Elliott Roosevelt by Kathleen Kinsolving (no photo)

by Kathleen Kinsolving (no photo)(no image) The President as Architect: Franklin D. Roosevelt's Top Cottage by John G Waite Associates (no photo)

(no image) The True Story of Fala by Margaret Suckley (no photo)

Edmund W. Starling

Edmund W. Starling

Colonel Edmund W. Starling was born 5 October 1875 in Christian County in the state of Kentucky. His father wore blue during the war in one of occupied-Kentucky’s Vichy regiments.

Edmund began his career in railroad security and policing with the Louisville and Nashville, and served in the secret service detail for five presidents from Woodrow Wilson to FDR.

Colonel Edmund W. Starling was the former head of the White House Secret Service.

He served for 30 years in Washington.

A funeral service for Colonel Edmund William Starling, former chief of the Secret Service detail in the White House, was conducted by the Red. George C. Hood, pastor of the Madison Avenue - Presbyterian Church - in the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Church, Madison Avenue and Eighty-first Street.

Colonel Starling died in the St. Luke's Hospital on August 5, 1944 at the age of 68. His ashes were buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

More:

http://www.visithopkinsville.com/even...

http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/ewst...

http://secretservicehistory.blogspot....

http://saicsecretserviceppd.blogspot....

http://kaiology.wordpress.com/tag/edm...

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/art...

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/art...

http://lib.law.virginia.edu/imtfe/con...

http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid...

by Edmund W. Starling (no photo)

by Edmund W. Starling (no photo) by Ronald Kessler (no photo)

by Ronald Kessler (no photo) by Andrew Meier (no photo)

by Andrew Meier (no photo) by Connie Colwell Miller (no photo)

by Connie Colwell Miller (no photo)(no image) The U.S. Secret Service by Ann Gaines (no photo)

(no image)Secret Service Story by Michael Dorman (no photo)

William Stephenson: Code Name Intrepid

William Stephenson: Code Name Intrepid

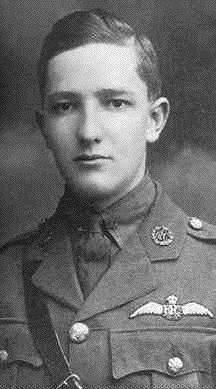

Stephenson was born William Samuel Clouston Stanger on 23 January 1897, in Point Douglas, Winnipeg, Manitoba. His mother was from Iceland, and his father was from the Orkney Islands. He was adopted early by an Icelandic family after his parents could no longer care for him, and given his foster parents' name, Stephenson.

He left school at a young age and worked as a telegrapher. In January 1916 he volunteered for service in the 101st Overseas Battalion (Winnipeg Light Infantry), Canadian Expeditionary Force. He left for England on the S.S. Olympic on 29 June 1916, arriving on 6 July 1916.

World War I

On 15 August 1917, Stephenson was officially struck off the strength of the Canadian Expeditionary Force and granted a commission in the Royal Flying Corps. Posted to 73 Squadron on 9 February 1918, he flew the British Sopwith Camel biplane fighter and scored 12 victories to become a flying ace before he was shot and crashed his plane behind enemy lines on 28 July 1918. During the incident Stephenson was injured by fire from a German ace pilot, Justus Grassmann, by friendly fire from a French observer, or by both. In any event he was subsequently captured by the Germans and held as a prisoner of war until he managed to escape in October 1918.

By the end of World War I, Stephenson had achieved the rank of Captain and earned the Military Cross and the Distinguished Flying Cross. His medal citations perhaps foreshadow his later achievements, and read:

"For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. When flying low and observing an open staff car on a road, he attacked it with such success that later it was seen lying in the ditch upside down. During the same flight he caused a stampede amongst some enemy transport horses on a road. Previous to this he had destroyed a hostile scout and a two-seater plane. His work has been of the highest order, and he has shown the greatest courage and energy in engaging every kind of target."

- Military Cross citation, Supplement to the London Gazette, 22 June 1919.

"This officer has shown conspicuous gallantry and skill in attacking enemy troops and transports from low altitudes, causing heavy casualties. His reports, also, have contained valuable and precise information. He has further proved himself a keen antagonist in the air, having, during recent operations, accounted for six enemy aeroplanes.

- Distinguished Flying Cross citation, Supplement to the London Gazette, 21 September 1928.

World War II

As early as April 1936, Stephenson was voluntarily providing confidential information to British opposition MP Winston Churchill about how Adolf Hitler's Nazi government was building up its armed forces and hiding military expenditures of eight hundred million pounds sterling. This was a clear violation of the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and showed the growing Nazi threat to European and international security. Churchill used Stephenson's information in Parliament to warn against the appeasement policies of the government of Neville Chamberlain.

After World War II began (and over the objections of Sir Stewart Menzies, wartime head of British intelligence) now-Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent Stephenson to the United States on 21 June 1940, to covertly establish and run British Security Coordination (BSC) in New York City, over a year before U.S. entry into the war.

BSC, with headquarters at Room 3603 Rockefeller Center, became an umbrella organization that by war's end represented the British intelligence agencies MI5, MI6 (the Secret Intelligence Service, or SIS), SOE (Special Operations Executive) and PWE (Political Warfare Executive) throughout North America, South America and the Caribbean.

Stephenson's initial directives for BSC were to 1) investigate enemy activities; 2) institute security measures against sabotage to British property; and 3) organize American public opinion in favour of aid to Britain. Later this was expanded to include "the assurance of American participation in secret activities throughout the world in the closest possible collaboration with the British". Stephenson's official title was British Passport Control Officer. His unofficial mission was to create a secret British intelligence network throughout the western hemisphere, and to operate covertly and broadly on behalf of the British government and the Allies in aid of winning the war. He also became Churchill's personal representative to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Stephenson was soon a close adviser to Roosevelt, and suggested that he put Stephenson's good friend William J. "Wild Bill" Donovan in charge of all U.S. intelligence services. Donovan founded the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which in 1947 would become the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). As senior representative of British intelligence in the western hemisphere, Stephenson was one of the few persons in the hemisphere who were authorized to view raw Ultra transcripts of German Enigma ciphers that had been decrypted at Britain's Bletchley Park facility. He was trusted by Churchill to decide what Ultra information to pass along to various branches of the U.S. and Canadian governments.

Under Stephenson, BSC directly influenced U.S. media (including newspaper columns by Walter Winchell and Drew Pearson), and media in other hemisphere countries, toward pro-British and anti-Axis views. Once the U.S. had entered the war in Dec. 1941, BSC went on to train U.S. propagandists from the United States Office of War Information in Canada. BSC covert intelligence and propaganda efforts directly affected wartime developments in Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Venezuela, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Mexico, the Central American countries, Bermuda, Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Stephenson worked without salary.He hired hundreds of people, mostly Canadian women, to staff his organization and covered much of the expense out of his own pocket. His employees included secretive communications genius Benjamin deForest "Pat" Bayly and future advertising wizard David Ogilvy. Stephenson employed Amy Elizabeth Thorpe, codenamed CYNTHIA, to seduce Vichy French officials into giving up Enigma ciphers and secrets from their Washington embassy. At the height of the war Bayly, a University of Toronto professor from Moose Jaw, created the Rockex, the fast secure communications system that would eventually be relied on by all the Allies.

Not least of Stephenson's contributions to the war effort was the setting up by BSC of Camp X in Whitby, Ontario, the first training school for clandestine operations in Canada and North America. Some 2,000 British, Canadian and American covert operators were trained there from 1941 to 1945, including students from ISO, OSS, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, United States Navy and Military Intelligence, and the United States Office of War Information, among them five future directors of what would become the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.

Camp X graduates operated in Europe (Spain, Portugal, Italy and the Balkans) as well as in Africa, Australia, India and the Pacific. They included Ian Fleming (though there is evidence to the contrary), future author of the James Bond books. It has been said that the fictional Goldfinger's raid on Fort Knox was inspired by a Stephenson plan (never carried out) to steal $2,883,000,000 in Vichy French gold reserves from the French Caribbean colony of Martinique.

BSC purchased from Philadelphia radio station WCAU a ten-kilowatt transmitter and installed it at Camp X. By mid-1944, Hydra (as the Camp X transmitter was known) was transmitting 30,000 and receiving 9,000 message groups daily — much of the secret Allied intelligence traffic across the Atlantic.

For his extraordinary service to the war effort, he was knighted into the order of Knights Bachelor by King George VI in the 1945 New Year's Honours List. In recommending Stephenson for knighthood, Winston Churchill wrote: "This one is dear to my heart."

In 1946 Stephenson received the Medal for Merit from President Harry S. Truman, at that time the highest U.S. civilian award; he was the first non-American to receive the medal. General "Wild Bill" Donovan presented the award. The citation paid tribute to Stephenson's "valuable assistance to America in the fields of intelligence and special operations".

The "Quiet Canadian" was recognized by his native land late: he was made a Companion of the Order of Canada on 17 December 1979, and invested in the Order on 5 February 1980.

Stephenson died on 31 January 1989, aged 92, in Paget, Bermuda. (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_...)

More:

http://www.nytimes.com/1989/02/03/obi...

http://commanderbond.net/2399/the-tru...

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...

http://www.trueintrepid.com/

http://www.angelfire.com/va/violettes...

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.co...

https://www.cia.gov/library/center-fo...

http://vault.fbi.gov/sir-william-step...

http://www.winstonchurchill.org/compo...

http://www.cbc.ca/thecurrent/episode/...

by

by

H. Montgomery Hyde

H. Montgomery Hyde by

by

Patrick K. O'Donnell

Patrick K. O'Donnell by William Stevenson (no photo)

by William Stevenson (no photo) by Bill MacDonald (no photo)

by Bill MacDonald (no photo) by Thomas F. Troy (no photo)

by Thomas F. Troy (no photo) by Edward Hymoff (no photo)

by Edward Hymoff (no photo)(no image) Camp X: OSS, Intrepid and the Allies' North American Training Camp for Secret Agents, 1941-1945 by David Stafford (no photo)

All,

This is a great opportunity to take advantage of a free course on the Second World War - this is an open course offered by Harvard:

World War II video lectures

CHARLES S. MAIER, PHD, LEVERETT SALTONSTALL PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

The course World War and Society in the Twentieth Century: World War II is a thematic exploration of the war and its time through feature films, primary sources, and scholarly interpretations.

It seeks to provide a means for analyzing and evaluating what one reads or sees about World War II in terms of historical accuracy and for gaining a broader understanding of different perspectives. Themes include the impact of war on soldiers and civilians, on the home front, women in war, the Japanese and German viewpoints, and postwar issues. Films include Mrs. Miniver, The Pianist, The Winter War, So Proudly We Hail, Taking Sides, The Hiding Place, and The Cranes Are Flying.

The lecture videos

The recorded lectures are from the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences course Historical Study B-54, which was offered as HIST E-1890, an online course at Harvard Extension School.

Watch the lectures as streaming video or audio. Each lecture is 50 minutes

http://www.extension.harvard.edu/open...

This is a great opportunity to take advantage of a free course on the Second World War - this is an open course offered by Harvard:

World War II video lectures

CHARLES S. MAIER, PHD, LEVERETT SALTONSTALL PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

The course World War and Society in the Twentieth Century: World War II is a thematic exploration of the war and its time through feature films, primary sources, and scholarly interpretations.

It seeks to provide a means for analyzing and evaluating what one reads or sees about World War II in terms of historical accuracy and for gaining a broader understanding of different perspectives. Themes include the impact of war on soldiers and civilians, on the home front, women in war, the Japanese and German viewpoints, and postwar issues. Films include Mrs. Miniver, The Pianist, The Winter War, So Proudly We Hail, Taking Sides, The Hiding Place, and The Cranes Are Flying.

The lecture videos

The recorded lectures are from the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences course Historical Study B-54, which was offered as HIST E-1890, an online course at Harvard Extension School.

Watch the lectures as streaming video or audio. Each lecture is 50 minutes

http://www.extension.harvard.edu/open...

Ralph Van Deman

Ralph Van Deman

Ralph Henry Van Deman (1865–1952) was a United States Army officer, sometimes called "The Father of American Military Intelligence."[citation needed] General Van Deman is in the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame.

Early career

Van Deman was born in Delaware, Ohio, and graduated from Harvard in 1888. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant of infantry in 1891 after attending law school, and enrolling in medical school. He received his medical degree from the Miami University Medical School in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1893.

Van Deman then entered the Army as a surgeon, before attending the Infantry and Cavalry School at Fort Leavenworth in early 1895. There he met Arthur L. Wagner who became head of the War Department's Military Information Division in 1896. In June 1897 Van Deman followed Wagner to Washington to work for MID.

Military Intelligence Division

During the Spanish-American War Van Deman collected information on the military capabilities of Spain in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines and had charge of the White House war map. At the end of hostilities he went to Cuba and Puerto Rico to collect cartographic data. He was reassigned to the Philippines in April 1899 as aide to Brigadier-General Robert Patterson Hughes. After two years he was promoted to Captain and was moved to the Bureau of Insurgent Records in Manila, which he helped transform into the Philippine Military Information Division. He organized a counter-intelligence group using locally-recruited agents. (See Philippine-American War).

He returned to the U.S. in late 1902, where he served as aide to the Commanding General, California, and then commanded Company B, 22nd Infantry, based at Fairbault, Minnesota. In 1904 he was one of nine officers selected for the first class of the Army War College (Another was John J. Pershing.) After graduation in 1906, he and Captain Alexander Coxe were sent on a covert mission to China to reconnoiter and map lines of communication around Peking. He returned to Washington in 1907 to become the Chief of the Mapping Section in the Second Division of the new General Staff. (On 26 October 1909 his wife became the first American woman to fly from American soil, being piloted by Wilbur Wright). He returned to the Philippines in 1910. There he resumed his project to map Chinese railways, roads and rivers until Japanese protests led to his expulsion in 1912.

Re-formation of MID

Back in the United States he taught cartography, then became Inspector-General with the 2nd Division. Now a major, he returned to the War College Division in July 1915. He found that there was a general apathy about intelligence-gathering, and the MID had been downgraded from the second division of the General Staff, and merged with the third division, ending its separate identity. Van Deman wrote a history of MID detailing its beginnings in 1885, its rise in 1903, and fall in subsequent years. He was convinced that the Army must have a coordinated intelligence organization if it were to avoid defeat in the near future, especially as it was now obvious that the U.S. would soon be involved in the war in Europe. Eventually Van Deman was able to get an audience with the Secretary of War to present his case. There he convinced the War Department to accept his idea of an intelligence department for U.S. forces. A crucial role was played by Colonel Claude Dansey of the British Security Service in proposing similar ideas to Colonel Edward M. House, a member of an American liaison mission to Britain and one of President Wilson's advisors.

World War I

As the result of these efforts the Military Intelligence Section, War College Division, War Department General Staff, was created on 3 May 1917, with Van Deman, now a Colonel, at its head. His friend and colleague Alexander Coxe was the first officer appointed. By the war's end in 1919, it had grown to 282 officers and 1,159 civilians, most of them specialists. One of these was Herbert Yardley, a cipher clerk with the State Department who Van Deman made a first lieutenant and put in charge of codes and ciphers.

Van Deman modelled his new organization on British Army intelligence, and divided it into several departments:

MI-1 - Administration

MI-2 - Information

MI-3 - Army Section (counterespionage)

MI-4 - Foreign Influence (counterespionage within the civilian community)

MI-5 - Military Attaches

MI-6 - Translation

MI-7 - Maps and Photographs

MI-8 - Codes and Ciphers

MI-9 - Combat Intelligence

MI-10 - News (censorship)

MI-11 - Travel (passport and port control)

MI-12 - Fraud

As well as military intelligence gathering, MID was also tasked with preventing sabotage and subversion by enemy agents or German sympathizers on US soil. Short of manpower, Van Deman relied on private groups which he organized into the American Protective League. He also provided security to government offices, defense plants, seaports, and other sensitive installations. He created a field organization in eight US cities which employed mobilized civilian policemen to perform security investigations. In France, MID provided operational intelligence to the American Expeditionary Force, and Van Deman created the Corps of Intelligence Police (forerunner of the Counter Intelligence Corps), recruiting fifty French-speaking Sergeants with police training. Thus, within a few months, he had created an intelligence organization that could support both domestic and tactical intelligence requirements.

Post-war activities

In 1918 Van Deman went to France to work for Colonel Dennis Nolan, G2 of the AEF, handing over control of the MID to Brigadier-General Marlborough Churchill. After overseeing security at the Paris Peace Commission, he returned to Washington in August 1919 to briefly serve as Deputy Chief of the MID. In March 1920 he returned to the army and commanded the 31st Infantry in the Philippines. He also spent three months on detached service with the British Army in India.

He returned to the US and had a series of tours with the National Guard. He worked in the Washington headquarters of the Militia Bureau, then served as an instructor with the 159th Infantry Brigade in Berkeley, California. As a Brigadier-General he commanded the 6th Infantry Brigade at Fort Rosecrans, San Diego, California from 1927. He was promoted to Major-General in May 1929, and commanded the 3rd Infantry Division at Fort Lewis, Washington. He retired in September 1929 after 38 years of service.

After retiring he used the contacts he had established during World War I in the American Protective League to privately compile files on suspected subversives and foreign agents.

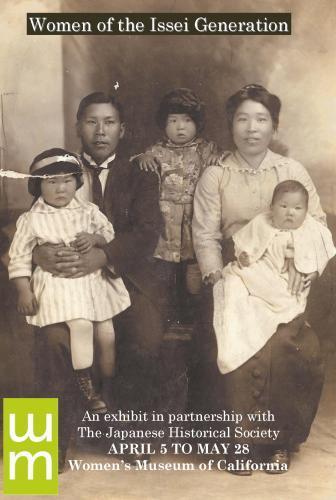

During World War II he acted as a consultant on intelligence matters to the War Department, for which he received a Legion of Merit. Notable among his recommendations was that he sent a passionate defense of Japanese-American citizens to President Roosevelt; the advice that they were not a threat was, however, ignored (leading to the Japanese American internment).

In January 1952, at the age of 86, he died in his home in San Diego.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Va...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Va...

http://huachuca-www.army.mil/files/hi...

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract...

http://projects.militarytimes.com/cit...

http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:...

by Brian McAllister Linn (no photo)

by Brian McAllister Linn (no photo) by Christopher H Sterling (no photo)

by Christopher H Sterling (no photo) by

by

Alfred W. McCoy

Alfred W. McCoy by Roy Talbert, JR. (no photo)

by Roy Talbert, JR. (no photo)(no image) Final Memoranda Major General Ralph H. Van Deman, USA Ret. 1865-1952, Father of U.S. Military Intelligence by Ralph H. Van Deman (no photo)

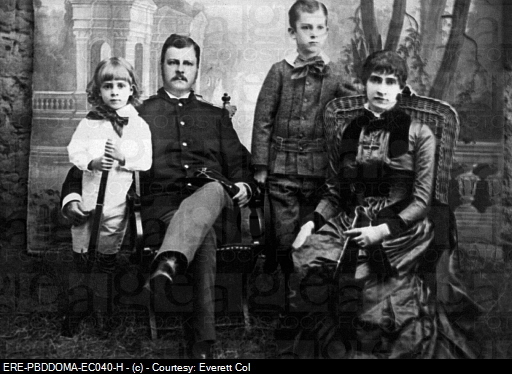

Arthur MacArthur, Jr.

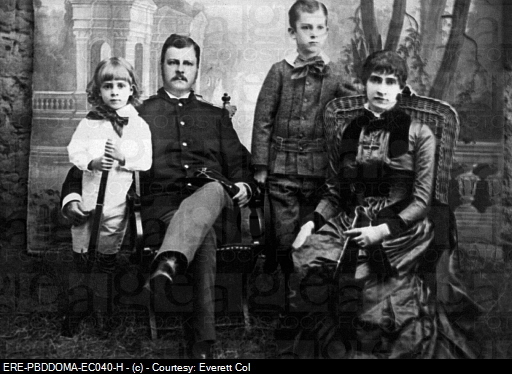

Lieutenant General Arthur MacArthur, Jr. (June 2, 1845 – September 5, 1912), was a United States Army general. He became the military Governor-General of the American-occupied Philippines in 1900 but his term ended a year later due to clashes with the civilian governor, future President William Howard Taft. His son, Douglas MacArthur, was one of only five men ever to be promoted to the five-star rank of General of the Army. In addition to their both being promoted to the rank of general officer, Arthur MacArthur, Jr. and Douglas MacArthur also share the distinction of having been the first father and son to each be awarded a Medal of Honor (the only other pair being Theodore Roosevelt and Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.).

Early life

Born in Chicopee Falls, then part of Springfield, Massachusetts, MacArthur was the father of General Douglas MacArthur, as well as Arthur MacArthur III, a captain in the Navy who was awarded the Navy Cross in World War I. His own father, Arthur MacArthur, Sr., was the fourth governor of Wisconsin (albeit for only four days) and a judge in Milwaukee.

Civil War

At the outbreak of the Civil War, MacArthur was living in Wisconsin. On August 4, 1862, at the age of 17, he was commissioned as a first lieutenant and appointed as adjutant of the 24th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment, seeing action at Chickamauga, Stones River, Chattanooga, the Atlanta Campaign and Franklin.

At the Battle of Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863 during the Chattanooga Campaign, the 18-year-old MacArthur inspired his regiment by seizing and planting the regimental flag on the crest of Missionary Ridge at a particularly critical moment, shouting "On Wisconsin." For these actions, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. He was brevetted colonel in the Union Army the following year. Only 19 years old at the time, he became nationally recognized as "The Boy Colonel" (not to be confused with Henry K. Burgwyn, known as the "Boy Colonel of the Confederacy").

He was promoted to major on January 25, 1864 and to lieutenant colonel on May 18, 1865 - shortly before he was mustered out of service on June 10, 1865.

In recognition of his gallantry in action he received brevets (honorary promotions) to lieutenant colonel and colonel dated March 15, 1865.

Indian Wars

With the conclusion of the Civil War in June 1865, MacArthur resigned his commission and began the study of law. After just a few months, however, he decided this was not a good fit for him, so he resumed his career with the Army. He was recommissioned on February 23, 1866 as a second lieutenant in the Regular Army's U.S. 17th Infantry Regiment, with a promotion the following day to first lieutenant. Because of his outstanding record of performance during the Civil War, he was promoted in September of that year to captain. However, he would remain a captain for the following two decades, as promotion was slow in the small peacetime army.

Between 1866 and 1884, Captain MacArthur and his wife (Mary Pinkney Hardy MacArthur) completed assignments in Pennsylvania, New York, Utah Territory, Louisiana, and Arkansas. Three children were born during this time:

- Arthur MacArthur III (born on August 1, 1876-died December 2, 1923 of Appendicitis)

- Malcolm MacArthur (born October 17, 1878, died 1883 of measles)

- Douglas MacArthur (born January 26, 1880, died April 5, 1964), at the Arsenal Barracks in Little Rock, Arkansas

In 1884, MacArthur became the post commander of Fort Selden, in New Mexico. The following year, he took part in the campaign against Geronimo. In 1889, he was promoted to Assistant Adjutant General of the Army with the rank of major, and was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1897.

Spanish-American War

During the first part of the Spanish American War, MacArthur was serving as the adjutant general of the III Corps in Georgia. In June 1898 he was promoted to a temporary Brigadier General in the volunteer army and commanded the Third Philippine Expedition. When he arrived in the Philippines he took command of the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, VIII Corps and led it at the Battle of Manila (1898). He was appointed Major General of volunteers on August 13, 1898.

Philippine-American War

MacArthur was stationed in the Dakota Territory when the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898 and was commissioned a Brigadier General of U.S. Volunteers. He led the U.S. 2nd Division, VIII Corps during the Philippine-American War at the Battle of Manila (1899), the Malolos campaign and the Northern Offensive. When the American occupation of the Philippines turned from conventional battles to guerrilla warfare, MacArthur commanded the Department of Northern Luzon. In January 1900, he was appointed Brigadier General in the regular army and was appointed military governor of the Philippines and assumed command of the VIII Corps, replacing General Elwell S. Otis.

He authorized the expedition, under General Frederick Funston, that resulted in the capture of Emilio Aguinaldo. MacArthur persuaded the captured Aguinaldo to cease fighting and to swear allegiance to the United States. He was promoted to major general in the Regular Army on February 5, 1901.

After the war, President William McKinley named him Military Governor of the Philippines, but the following year, William Howard Taft was appointed as Civilian Governor. Taft and MacArthur clashed frequently. So severe were his difficulties with Taft over U.S. military actions in the war that MacArthur was eventually relieved and transferred to command the Department of the Pacific, where he was promoted to lieutenant general.

Return to the United States

In the years that followed, he was assigned to various stateside posts and in 1905 was sent to Manchuria to observe the final stages of the Russo-Japanese War and served as military attaché to the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo. He returned to the U.S. in 1906 and resumed his post as Commander of the Pacific Division. That year the position of Army Chief of Staff became available and he was then the highest-ranking officer in the Army as a lieutenant general (three stars). However, he was passed over by Secretary of War William Howard Taft. He never did realize his dream of commanding the entire Army.

Retirement

MacArthur retired from the Army on June 2, 1909, having reached the mandatory retirement age of 64. He was one of the last officers on active duty in the Army who had served in the Civil War.

MacArthur was elected a member of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS) in 1868 and was assigned insignia number 648. On May 6, 1908 he was elected commander of the Wisconsin Commandery of MOLLUS. He was elected as the Order's senior vice commander in chief on October 18, 1911 and became the Order's commander in chief upon the death of Rear Admiral George T. Melville on March 12, 1912.

On September 5, 1912, he went to Milwaukee to address a reunion of his Civil War unit. While on the dais, he suffered a heart attack and died there, aged 67. He was originally buried in Milwaukee on Monday, September 7, 1912, but was moved to Section 2 of Arlington National Cemetery in 1926. He is buried among other members of the family there, while his son, Douglas chose to be buried in Norfolk, Virginia.

(Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_....)

More:

http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/amac...

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/macarthu...

http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/dicti...

http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/wlhba...

http://www.spanamwar.com/macarthur.htm

by

by

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur

by D. Clayton James (no photo)

by D. Clayton James (no photo)

by Kenneth Ray Yound (no photo)

by Kenneth Ray Yound (no photo)

by James H. Willbanks (no photo)

by James H. Willbanks (no photo)

by

by

William Raymond Manchester

William Raymond Manchester

edited by David S. Heidler (no photo)

edited by David S. Heidler (no photo)

Lieutenant General Arthur MacArthur, Jr. (June 2, 1845 – September 5, 1912), was a United States Army general. He became the military Governor-General of the American-occupied Philippines in 1900 but his term ended a year later due to clashes with the civilian governor, future President William Howard Taft. His son, Douglas MacArthur, was one of only five men ever to be promoted to the five-star rank of General of the Army. In addition to their both being promoted to the rank of general officer, Arthur MacArthur, Jr. and Douglas MacArthur also share the distinction of having been the first father and son to each be awarded a Medal of Honor (the only other pair being Theodore Roosevelt and Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.).

Early life

Born in Chicopee Falls, then part of Springfield, Massachusetts, MacArthur was the father of General Douglas MacArthur, as well as Arthur MacArthur III, a captain in the Navy who was awarded the Navy Cross in World War I. His own father, Arthur MacArthur, Sr., was the fourth governor of Wisconsin (albeit for only four days) and a judge in Milwaukee.

Civil War

At the outbreak of the Civil War, MacArthur was living in Wisconsin. On August 4, 1862, at the age of 17, he was commissioned as a first lieutenant and appointed as adjutant of the 24th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment, seeing action at Chickamauga, Stones River, Chattanooga, the Atlanta Campaign and Franklin.

At the Battle of Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863 during the Chattanooga Campaign, the 18-year-old MacArthur inspired his regiment by seizing and planting the regimental flag on the crest of Missionary Ridge at a particularly critical moment, shouting "On Wisconsin." For these actions, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. He was brevetted colonel in the Union Army the following year. Only 19 years old at the time, he became nationally recognized as "The Boy Colonel" (not to be confused with Henry K. Burgwyn, known as the "Boy Colonel of the Confederacy").

He was promoted to major on January 25, 1864 and to lieutenant colonel on May 18, 1865 - shortly before he was mustered out of service on June 10, 1865.

In recognition of his gallantry in action he received brevets (honorary promotions) to lieutenant colonel and colonel dated March 15, 1865.

Indian Wars

With the conclusion of the Civil War in June 1865, MacArthur resigned his commission and began the study of law. After just a few months, however, he decided this was not a good fit for him, so he resumed his career with the Army. He was recommissioned on February 23, 1866 as a second lieutenant in the Regular Army's U.S. 17th Infantry Regiment, with a promotion the following day to first lieutenant. Because of his outstanding record of performance during the Civil War, he was promoted in September of that year to captain. However, he would remain a captain for the following two decades, as promotion was slow in the small peacetime army.

Between 1866 and 1884, Captain MacArthur and his wife (Mary Pinkney Hardy MacArthur) completed assignments in Pennsylvania, New York, Utah Territory, Louisiana, and Arkansas. Three children were born during this time:

- Arthur MacArthur III (born on August 1, 1876-died December 2, 1923 of Appendicitis)

- Malcolm MacArthur (born October 17, 1878, died 1883 of measles)

- Douglas MacArthur (born January 26, 1880, died April 5, 1964), at the Arsenal Barracks in Little Rock, Arkansas

In 1884, MacArthur became the post commander of Fort Selden, in New Mexico. The following year, he took part in the campaign against Geronimo. In 1889, he was promoted to Assistant Adjutant General of the Army with the rank of major, and was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1897.

Spanish-American War

During the first part of the Spanish American War, MacArthur was serving as the adjutant general of the III Corps in Georgia. In June 1898 he was promoted to a temporary Brigadier General in the volunteer army and commanded the Third Philippine Expedition. When he arrived in the Philippines he took command of the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, VIII Corps and led it at the Battle of Manila (1898). He was appointed Major General of volunteers on August 13, 1898.

Philippine-American War

MacArthur was stationed in the Dakota Territory when the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898 and was commissioned a Brigadier General of U.S. Volunteers. He led the U.S. 2nd Division, VIII Corps during the Philippine-American War at the Battle of Manila (1899), the Malolos campaign and the Northern Offensive. When the American occupation of the Philippines turned from conventional battles to guerrilla warfare, MacArthur commanded the Department of Northern Luzon. In January 1900, he was appointed Brigadier General in the regular army and was appointed military governor of the Philippines and assumed command of the VIII Corps, replacing General Elwell S. Otis.

He authorized the expedition, under General Frederick Funston, that resulted in the capture of Emilio Aguinaldo. MacArthur persuaded the captured Aguinaldo to cease fighting and to swear allegiance to the United States. He was promoted to major general in the Regular Army on February 5, 1901.

After the war, President William McKinley named him Military Governor of the Philippines, but the following year, William Howard Taft was appointed as Civilian Governor. Taft and MacArthur clashed frequently. So severe were his difficulties with Taft over U.S. military actions in the war that MacArthur was eventually relieved and transferred to command the Department of the Pacific, where he was promoted to lieutenant general.

Return to the United States

In the years that followed, he was assigned to various stateside posts and in 1905 was sent to Manchuria to observe the final stages of the Russo-Japanese War and served as military attaché to the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo. He returned to the U.S. in 1906 and resumed his post as Commander of the Pacific Division. That year the position of Army Chief of Staff became available and he was then the highest-ranking officer in the Army as a lieutenant general (three stars). However, he was passed over by Secretary of War William Howard Taft. He never did realize his dream of commanding the entire Army.

Retirement

MacArthur retired from the Army on June 2, 1909, having reached the mandatory retirement age of 64. He was one of the last officers on active duty in the Army who had served in the Civil War.

MacArthur was elected a member of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS) in 1868 and was assigned insignia number 648. On May 6, 1908 he was elected commander of the Wisconsin Commandery of MOLLUS. He was elected as the Order's senior vice commander in chief on October 18, 1911 and became the Order's commander in chief upon the death of Rear Admiral George T. Melville on March 12, 1912.

On September 5, 1912, he went to Milwaukee to address a reunion of his Civil War unit. While on the dais, he suffered a heart attack and died there, aged 67. He was originally buried in Milwaukee on Monday, September 7, 1912, but was moved to Section 2 of Arlington National Cemetery in 1926. He is buried among other members of the family there, while his son, Douglas chose to be buried in Norfolk, Virginia.

(Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_....)

More:

http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/amac...

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/macarthu...

http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/dicti...

http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/wlhba...

http://www.spanamwar.com/macarthur.htm

by

by

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur by D. Clayton James (no photo)

by D. Clayton James (no photo) by Kenneth Ray Yound (no photo)

by Kenneth Ray Yound (no photo) by James H. Willbanks (no photo)

by James H. Willbanks (no photo) by

by

William Raymond Manchester

William Raymond Manchester edited by David S. Heidler (no photo)

edited by David S. Heidler (no photo)

Field Marshal Sir John Dill

Field Marshal Sir John Dill

Dill was born in Lurgan on 25 December 1881, son of the local bank manager. He attended Cheltenham College and the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. In 1901 he joined the 1st battalion of the Leinster regiment and saw action in the Second Boer War.

On the outbreak of the World War I he became brigade-major of the 25th brigade (8th division) in France where he was present at Neuve Chapelle, Alvers Ridge and Bois Grenier. By the end of the war he was a brigadier general, had been wounded in action and mentioned in despatches eight times. After the war he gained a reputation as a gifted army instructor. He was promoted to major general in 1930, taking up appointments at the Staff College and then in the War Office.

Dill commanded British forces in Palestine (1936 - 1937). He was commander of I Corps in France (1939-40), returning to the UK in April 1940 when he was appointed Vice Chief of the Imperial General Staff by the then Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. In May 1940, after Churchill had replaced Chamberlain, Dill was appointed as CIGS. Later in 1940, he became ADC General to King George VI.

By the time Churchill worked with Dill as Chief of the Imperial General Staff it was clear how poorly the two men got on. Dill gained a reputation as obstructive and unimaginative. To get him out of the way, Churchill posted him to Washington as his personal representative in 1941 where he became Chief of the British Joint Staff Mission, then Senior British Representative on the Combined Chiefs of Staff.

In Washington Dill found his feet, excelling as a diplomatic military presence. In 1943 alone he attended the Conferences in Quebec, Casablanca and Tehran, and also meetings in India, China and Brazil. He served briefly on the combined policy committee set up by the British and United States governments under the Quebec Agreement to oversee the construction of the atomic bomb.

He was immensely important in making the Chiefs of Staff committee - which included members from both countries - function, often smoothing ruffled feathers in the clash of cultures that followed. He was particularly friendly with General George Marshall (he of the Marshall Plan) and the two exercised a great deal of influence on President Roosevelt who described Dill as "the most important figure in the remarkable accord that has been developed in the combined operations of our two countries".

Dill served in Washington until his death in November 1944. Following a memorial service in Washington Cathedral he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. He was posthumously awarded an American Distinguished Service Medal in 1945 as well as receiving an unprecedented joint resolution of Congress appreciating his services.

An equestrian statue in his honour was unveiled by President Harry S Truman in Arlington National Cemetery in November 1950.

(Source: http://www.ulsterhistory.co.uk/dill.htm)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dill

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-hi...

http://www.kingscollections.org/catal...

http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/jgdi...

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg....

http://www.marshallfoundation.org/pdf...

http://www.thepeerage.com/p38211.htm

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/t...

http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/PSF...

http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307...

http://www.defensemedianetwork.com/st...

by

by

Rick Atkinson

Rick Atkinson by

by

William Raymond Manchester

William Raymond Manchester  by

by

John Keegan

John Keegan(no image) Dictionary of Field Marshals of the British Army by T.A. Heathcote (no photo)

(no image) Very Special Relationship: Field-Marshall Sir John Dill and the Anglo-American Alliance, 1941-44 by

Alex Danchev

Alex Danchev

Kathleen Harriman

Kathleen Harriman

Kathleen Harriman Mortimer, the younger of the two daughters of W. Averell Harriman and his first wife Kitty Lanier Lawrance, died at age ninety-three on February 17th in her cottage at Arden, New York. Mrs. Mortimer grew up in town houses in New York City and estates on Long Island, Aiken, South Carolina, and in a 100,000 square foot house designed by Carrere & Hastings, perched at the highest point in the Ramapo River Valley with sweeping views. Commissioned by her grandfather, Union Pacific Railroad magnate Edward Henry Harriman, Arden House had a funicular for taking guests and supplies up the mountain and even the occasional horse, either for riding or a visit to the halls of the house, which happened on more than one occasion. Growing up in a large house with a massive organ in a cathedral-ceilinged music room had its drawbacks. Mrs. Mortimer was made by her grandmother the richest woman in America upon the death of her husband to sit through endless Sunday recitals of guest organists, which put her off organ music for the rest of her life. Like her father, Mrs. Mortimer was a fearless, natural athlete: a crack shot, tennis and golf player, fisherwoman, and, at the Foxcroft School, a member of the elite riding team distinguished by their Garibaldi-style lamb's fur hats. Instead of attending one of the more traditional Seven Sisters women's colleges, Mrs. Mortimer chose Bennington, where she was a member of its fourth graduating class. There she skied on Mount Washington before going on to become a leading racer on the East Coast as well as one of the champion women skiers at the resort of Sun Valley, Idaho, founded in 1936 by her father, as a destination for the Union Pacific Railroad. In 1940, Mrs. Mortimer was chosen as an alternate for the U.S. Olympic Ski Team, but decided to stay in college and graduate rather than train. Well into her 70s she could be seen schussing down Sun Valley runs with her friend Gretchen Fraser, the first American to win an Olympic gold medal for skiing, in 1948.

At age twenty-three, in 1941, Mrs. Mortimer joined her father in London where he was administrator for the Lend-Lease Act and served as the principal liaison between President Roosevelt and the British government. She had only planned to stay a short time but instead became a reporter for Hearst's International News Service and Newsweek magazine. In London she shared an apartment with Pamela Digby Churchill and turned over her paycheck to the always strapped for cash daughterin-law of the prime minister. Thirty years later her former roommate would become her step-mother. It was in the middle of a birthday party given for her by Prime Minister Winston Churchill at his country estate Chequers on December 7, 1942 that Churchill and the other guests learned of the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

When her father was appointed Ambassador to Russia in 1943, he took his daughter, who acted as his hostess at Spaso House in Moscow where Lillian Hellman stayed for a while in Mrs. Mortimer's sitting room recovering from pneumonia. George F. Kennan, the senior career Foreign Service officer in Moscow, commented that blessedly Mrs. Mortimer had--very un-Harriman-like--a sense of humor. During that time, Mrs. Mortimer worked at the Office of War Information, visited hospitals, came in third in the 1943 Moscow slalom championships, acted as her father's interpreter with her basic Russian, and accompanied him everywhere meeting every important figure in Europe and Russia during World War II.

In 1944 Ambassador Harriman placed his daughter in the middle of one of the most highly sensitive situations of the war--the Soviet attempt to escape blame for the massacre of the Polish Army officers when the Russian Army occupied eastern Poland. That year, along with seventeen western correspondents, Mrs. Mortimer was transported by a luxurious train and then driven into the Katyn Forest where the mass graves had been opened, and the thousands of disintegrating bodies had been laid out in tents, so autopsies could be observed. Based on her and the other reporters' notes, Germany was blamed. The Russians continued to deny responsibility for the massacre until 1990.

At the beginning of 1945 Mrs. Mortimer boarded a train to Yalta two weeks in advance of the conference attended by Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin in order to prepare accommodations for the large American contingent at the climatic meeting of the war. She came away very skeptical about Stalin. Two months later the U.S.-Soviet relationship had disintegrated. In January, a year later, Mrs. Mortimer left Moscow with her father via the Far East where they met with Chiang Kai-shek and General George Marshall. Several months later two Russian thoroughbred stallions called Fact and Boston arrived in New York as a farewell gift to the Harrimans from Stalin.

According to Harriman biographer Rudy Abramson, Having been pursued through the war by journalists, diplomats, and military officers, including Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr., Kathleen returned to New York and became engaged to Stanley G. Mortimer, Jr. who had grown up in Tuxedo Park just down the road from Arden. Mr. Mortimer was a Standard Oil heir and advertising executive, and had been married to Barbara Cushing Paley.

Mrs. Mortimer was indefatigable in campaigning for her father in his runs for political office as governor of New York State in 1954 and 1958 as well as for the candidacy for the Democratic Presidential Nomination in 1952, and again in 1956 when he was endorsed by Truman. Harriman lost, both times, to Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson.

An activist, but raised with old school beliefs and finding notoriety unseemly, Mrs. Mortimer was greatly influenced by her aunt Mary Harriman Rumsey, who founded the Junior League in 1901 as a Barnard College student and mobilized eighty of her friends, including Eleanor Roosevelt, to work to improve settlement houses in New York. Mrs. Mortimer followed her aunt's example and remained engaged throughout her life in health care, educational, public policy, and philanthropic interests. She was on the board of trustees of the Visiting Nurse Service, The Harriman Institute, the Foundation for Child Development, The American Assembly, Bennington College, among other organizations, and she was president of the Mary W. Harriman Foundation. Several years ago a foundation was renamed the Mary and Kathleen Harriman Foundation in honor of Mrs. Mortimer and her sister Mary Fisk.

Mrs. Mortimer remained a competitive amateur athlete all her life and seemed prouder of her three sons' athletic achievements than anything else. She and her husband hosted spaniel field trials in Arden, and she continued to exercise horses into her mid 80s. She is survived by her sons, David, Jay, and Averell Mortimer of New York, her stepson, Stanley G. Mortimer III of Palm Beach and stepdaughter, Amanda M. Burden of New York; ten grandchildren, and seven great grandchildren.

(Source: http://www.recordonline.com/apps/pbcs...)

More:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/20/us/...

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm1540465/bio

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obitu...

http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid...

http://www.vanityfair.com/society/fea...

http://lawandconversation.com/tag/kat...

http://bangordailynews.com/2008/09/25...

http://doug-stern.com/blog/tag/kathle...

http://newdeal.feri.org/kiosk/profile...

http://www.smokershistory.com/Harrima...

http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/obi...

by

by

William Raymond Manchester

William Raymond Manchester  by

by

Lynne Olson

Lynne Olson by

by

Doris Kearns Goodwin

Doris Kearns Goodwin by

by

Jon Meacham

Jon Meacham by

by

Michael Dobbs

Michael Dobbs by Frank Costigliola (no photo)

by Frank Costigliola (no photo)

William F. Friedman

William F. Friedman

Wolfe Frederick Friedman was born on 24 September 1891 in Kishinev, then part of imperial Russia, now Chisinau, capital of Moldova. His father, an interpreter for the Czar's postal service, emigrated to the United States the following year to escape increasing anti-Semitic regulations; the family joined him in Pittsburgh in 1893. Three years after that, when the elder Friedman became a U.S. citizen, Wolfe's name was changed to William.

After receiving a B.S. and doing some graduate work in genetics at Cornell University, William Friedman was hired by Riverbank Laboratories, what would today be termed a "think tank," outside Chicago. There he became interested in the study of codes and ciphers, thanks to his concurrent interest in Elizebeth Smith, who was doing cryptanalytic research at Riverbank. Friedman left Riverbank to become a cryptologic officer during World War I, the beginning of a distinguished career in government service.

Friedman's contributions thereafter are well known-- prolific author, teacher, and practitioner of cryptology. Perhaps his greatest achievements were introducing mathematical and scientific methods into cryptology and producing training materials used by several generations of pupils. His work affected for the better both signals intelligence and information systems security, and much of what is done today at NSA may be traced to William Friedman's pioneering efforts.

To commemorate the contributions of the Friedmans, in 2002 the OPS1 building on the NSA complex was dedicated as the William and Elizebeth Friedman Building.

(Source: http://www.nsa.gov/about/cryptologic_...)

More:

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/t...

http://www.nsa.gov/public_info/_files...

http://www.loc.gov/vets/stories/intel...

http://history.howstuffworks.com/amer...

http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_...

http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstrac...

http://marshallfoundation.org/library...

http://www.giac.org/paper/gsec/431/co...

http://www.nku.edu/~christensen/secti...

http://intellit.muskingum.edu/cryptog...

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10...

(no image) The Story of Magic: Memoirs of an American Cryptologic Pioneer by Frank B. Rowlett (no photo)

(no image) The Man Who Broke Purple: The Life of the World's Greatest Cryptologist, William F. Friedman by Ronald William Clark (no photo)

by

by

James Gannon

James Gannon by David Kahn (no photo)

by David Kahn (no photo)

by William F. Friedman (no photo)

by William F. Friedman (no photo)

Hamilton Fish, III

Hamilton Fish, III

Hamilton Fish, (son of Hamilton Fish [1849-1936], grandson of Hamilton Fish [1808-1893], and father of Hamilton Fish, Jr. [1926-1996]), a Representative from New York; born in Garrison, Putnam County, N.Y., December 7, 1888; attended St. Marks School; was graduated from Harvard University in 1910; elected as a Progressive to the New York State assembly, 1914-1916; commissioned on July 15, 1917, captain of Company K, Fifteenth New York National Guard (colored), which subsequently became the Three Hundred and Sixty-ninth Infantry; was discharged as a major on May 14, 1919; decorated with the Croix de Guerre and the American Silver Star and also cited in War Department general orders; colonel in the Officers’ Reserve Corps; delegate, Republican National Convention, 1928; elected as a Republican to the Sixty-sixth Congress to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Edmund Platt; reelected to the Sixty-seventh and to the eleven succeeding Congresses and served from November 2, 1920, to January 3, 1945; unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1944 to the Seventy-ninth Congress; author; was a resident of Cold Spring, N.Y., until his death there on January 18, 1991; interment in Cemetery of Saint Philip’s Church in the Highlands, Garrison, N.Y.

(Source: http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamilton...

http://digitalhistory.hsp.org/node/5246

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg....

http://www.nndb.com/people/911/000364...

http://newstalgia.crooksandliars.com/...

http://youtu.be/TYJLP8LkKls

http://articles.latimes.com/1991-01-2...

http://www.hudsonrivervalley.org/libr...

http://desmondfishlibrary.org/lisa/li...

http://www.footballfoundation.org/Pro...

(no image) FDR: The Other Side Of The Coin by Hamilton Fish (no photo)

(no image) Tragic Deception: FDR and America's Involvement in World War II by Hamilton Fish (no photo)

(no image) Americans, Save Your Freedom And Your Lives by Hamilton Fish (no photo)

(no image) Americans, Save Your Freedom And Your Lives by Hamilton Fish (no photo)

by Martin B. Gold (no photo)

by Martin B. Gold (no photo) by Hatsue Shinohara (no photo)

by Hatsue Shinohara (no photo) by Hamilton Fish (no photo)

by Hamilton Fish (no photo)

USS Arizona

USS Arizona

USS Arizona, a 31,400 ton Pennsylvania class battleship built at the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, New York, was commissioned in October 1916. After shakedown off the east coast and in the Caribbean, she operated out of Norfolk, Virginia, until November 1918, when she made a brief cruise to France. She made a second cruise to European waters in April-June 1919, proceeding as far east as Turkey. During much of 1920-21, the battleship was in the western Atlantic and Caribbean areas, but paid two visits to Peru in 1921 in her first excursions into the Pacific. From August 1921 until 1929, Arizona was based in Southern California, making occasional cruises to the Caribbean or Hawaii during major U.S. Fleet exercises.

In 1929-31, Arizona was modernized at the Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Virginia, emerging with a radically altered appearance and major improvements to her armament and protection. In March 1931, she transported President Herbert Hoover and his party to Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. In August of that year, Arizona returned to the Pacific, continuing her operations with the Battle Fleet during the next decade. From 1940, she, and the other Pacific Fleet battleships, were based at Pearl Harbor on the orders of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Arizona was moored in Pearl Harbor's "Battleship Row" on the morning of 7 December 1941, when Japanese carrier aircraft attacked. She was hit by several bombs, one of which penetrated her forecastle and detonated her forward ammunition magazines. The resulting massive explosion totally wrecked the ship's forward hull, collapsing her forward superstructure and causing her to sink, with the loss of over 1100 of her crewmen. In the following months, much of her armament and topside structure was removed, with the two after triple 14" gun turrets being transferred to the Army for emplacement as coast defense batteries on Oahu.

The wrecked battleship's hull remained where she sank, a tomb for many of those lost with her. In 1950, she began to be used as a site for memorial ceremonies, and, in the early 1960s a handsome memorial structure was constructed over her midships hull. This USS Arizona Memorial, operated by the National Park Service, is a permanent shrine to those Americans who lost their lives in the attack on Pearl Harbor and in the great Pacific War that began there.

(Source: http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/sh...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Ariz...

http://www.nps.gov/valr/index.htm

http://www.ussarizona.org/

http://www.library.arizona.edu/exhibi...

http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/s...

http://www.hnsa.org/ships/arizona.htm

by Joy Waldron Jasper (no photo)

by Joy Waldron Jasper (no photo) by Maureen Picard Robins (no photo)

by Maureen Picard Robins (no photo) by Norman Friedman (no photo)

by Norman Friedman (no photo) by

by

Daniel Lenihan

Daniel Lenihan by

by

Gordon W. Prange

Gordon W. Prange

Tripartite Pact (1940)

Tripartite Pact (1940)

On this day in [September 27] 1940, the Axis powers are formed as Germany, Italy, and Japan become allies with the signing of the Tripartite Pact in Berlin. The Pact provided for mutual assistance should any of the signatories suffer attack by any nation not already involved in the war. This formalizing of the alliance was aimed directly at "neutral" America--designed to force the United States to think twice before venturing in on the side of the Allies.

The Pact also recognized the two spheres of influence. Japan acknowledged "the leadership of Germany and Italy in the establishment of a new order in Europe," while Japan was granted lordship over "Greater East Asia."

(Source: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-hi...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triparti...

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/j...

http://histclo.com/essay/war/ww2/camp...

https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hQ_Fda...

by Source Wikipedia (no photo)

by Source Wikipedia (no photo) by Bernhard Kroener (no photo)

by Bernhard Kroener (no photo) by Wippich Rolf-Ha (no photo)

by Wippich Rolf-Ha (no photo) by Gordon A. Craig (no photo)

by Gordon A. Craig (no photo)(no image) Japan at War: An Encyclopedia by Louis G Perez (no photo)

message 167:

by

Jerome, Assisting Moderator - Upcoming Books and Releases

(new)

Sara Delano Roosevelt

Sara Delano Roosevelt (SDR) was the daughter of Warren Delano, a wealthy merchant who made a fortune in the tea and opium trade in China, and after losing it, returned to make a second fortune. Sara grew up in Hong Kong from 1862-65 and in Algonac, the family estate on the Hudson River near Newburgh, New York. She was educated at home, except for a short period in 1867 when she attended a school for girls in Dresden, Germany. Sara Delano was tall and radiantly beautiful and had many suitors. At twenty-six, to the surprise of her friends, she married James Roosevelt, a widower who was twice her age. By all accounts, she found great happiness in her marriage and in life on her husband's Hyde Park, New York, estate. After the birth of Franklin Delano Roosevelton January 30, 1882, she was advised to have no more children. She became absorbed in raising her only son, reading to him, giving him baths, and directing his activities herself rather than leaving these tasks to servants. After the death of her husband in 1900, she became still more single-mindedly focused on her son and his welfare. She moved temporarily to Boston when he attended Harvard in order to be near him. No mother could have been more devoted. She was also strong willed, controlling, opinionated, and inflexible. She does not seem to have been enthusiastic about any of the young women her son courted and, when he fell in love and proposed marriage to Eleanor Roosevelt, she tried to change his mind and insisted that the engagement be kept secret for a year.