The Fyodor Dostoyevsky Group discussion

This topic is about

The Brothers Karamazov

The Brothers Karamazov

>

Week II - 7/02/2014 - 13/02/2014 - Book III

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Samadrita, Creator cum Novice Moderator

(last edited Jan 08, 2014 01:10AM)

(new)

-

rated it 3 stars

Jan 07, 2014 11:15PM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

His wife, Marfa Ignatyevna, had obeyed her husband's will implicitly all her life, yet she had pestered him terribly after the emancipation of the serfs. (III.1)

His wife, Marfa Ignatyevna, had obeyed her husband's will implicitly all her life, yet she had pestered him terribly after the emancipation of the serfs. (III.1)

The muzhiks listening to the proclamation of the Emancipation Manifesto in 1861 by B. Kustodiev (1907)

The Emancipation Reform of 1861 in Russia (Russian: Крестьянская реформа 1861 года, Krestyanskaya reforma 1861 goda, lit. "The Peasant Reform of 1861") was the first and most important of liberal reforms effected during the reign of Alexander II of Russia. The reform, together with a related reform in 1861, amounted to the liquidation of serf dependence previously suffered by peasants of the Russian Empire. In some of its parts, the serfdom was abolished earlier.

The 1861 Emancipation Manifesto proclaimed the emancipation of the serfs on private estates and of the domestic (household) serfs. By this edict more than 23 million people received their liberty. Serfs were granted the full rights of free citizens, gaining the rights to marry without having to gain consent, to own property and to own a business. The Manifesto prescribed that peasants would be able to buy the land from the landlords. Household serfs were the worst affected as they gained only their freedom and no land.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serfdom_...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emancipa...

Nikolay Nekrasov

Nikolay NekrasovThe lines quoted by Dmitri in III.3 are taken from a poem by Nekrasov (and later Ivan will quote more Nekrasov):

“That's brandy,” Mitya laughed. “I see your look: ‘He's drinking again!’ Distrust the apparition.

Distrust the worthless, lying crowd,(III.3)

And lay aside thy doubts.

Here is Nekrasov's poem (but in French):

http://books.google.fr/books?id=YvMAE...

Found the poem in English:

When from thine error, dark, degrading,

With words of fiery persuading,

I drew thy fallen spirit out;

And thou, thy hands in anguish wringing,

Didst curse, filled with a torment stinging,

The sin that compassed thee about;

When thou, thy conscience dilatory

Chastising with the memory's shame,

Didst there unfold to me the story

Of that which was before I came;

And sudden with thy two hands shielding

In loathing and dismay thy face,

To floods of tears I saw thee yielding,

O'erwhelmed, yea prostrate with disgraceÑ

Trust me! Thy tale did not importune;

I caught each word and tired not.

I understood, child of misfortune!

I pardoned all, and all forgot.

Why is it then, a secret doubting

Still preys upon thee every hour?

The world's opinion, thoughtless flouting,

Holds even thee too in its power?

Heed not the world, its lies dissembling,

Henceforth from all thy doubts be free;

Nor let thy soul, unduly trembling,

Still harbor thoughts that torture thee.

By grieving fruitlessly and vainly

Warm not the serpents in thy breast,

Into my house come bold and free,

Its rightful mistress there to be.

http://www.macalester.edu/~hammarberg...

A snippet of commentary on the use of Nekrasov by Dostoevsky:

http://books.google.fr/books?id=eaoZZ...

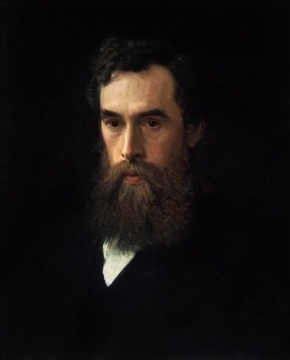

Painting by Kramskoy (1878)

Nikolay Alexeyevich Nekrasov (Russian: Никола́й Алексе́евич Некра́сов, December 10 [O.S. November 28] 1821 – 8 January 1878 [O.S. 28 December 1877]) was a Russian poet, writer, critic and publisher, whose deeply compassionate poems about peasant Russia won him Fyodor Dostoyevsky's admiration and made him the hero of liberal and radical circles of Russian intelligentsia, as represented by Vissarion Belinsky and Nikolay Chernyshevsky.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikolay_...

http://persona.rin.ru/eng/view/f/0/10...

BP, thank you for your posts full of priceless new insights as ever. I had no idea about Nekrasov.

Samadrita wrote: "BP, thank you for your posts full of priceless new insights as ever. I had no idea about Nekrasov."

Samadrita wrote: "BP, thank you for your posts full of priceless new insights as ever. I had no idea about Nekrasov."I'm a helpless hoarder of internet links & pics. :) It's surprising that Nekrasov's poetry is not more widely available online.

So, what's your take on Smerdyakov? is he, or isn't he a Karamazov? based on the information given so far, the narrator makes it possible but not a certainty. I've just read his chapter on faith and reason and he proves he can hold his own in an argument with the other members of the family all right.

So, what's your take on Smerdyakov? is he, or isn't he a Karamazov? based on the information given so far, the narrator makes it possible but not a certainty. I've just read his chapter on faith and reason and he proves he can hold his own in an argument with the other members of the family all right.

Algernon wrote: "So, what's your take on Smerdyakov? is he, or isn't he a Karamazov? based on the information given so far, the narrator makes it possible but not a certainty. I've just read his chapter on faith an..."

Yes. I do think Smerdyakov is a Karamazov (perfectly expected of a vile, unconscionable man like Fyodor Pavlovich to impregnate a destitute woman who has lost her mind) and it seems like his horse is hitched to atheism just like Ivan's.

Yes. I do think Smerdyakov is a Karamazov (perfectly expected of a vile, unconscionable man like Fyodor Pavlovich to impregnate a destitute woman who has lost her mind) and it seems like his horse is hitched to atheism just like Ivan's.

I agree with Samadrita, Algernon.

I think Smerdyakov is Fyodor's bastard and that he might have possibly taken advantage (or even raped) his retarded mother, "stinking Lizaveta".

Great posts Book Portrait. I wondered what Dostoevsky thought about those "modern" reforms, specially since despicable Rakitin vouched for the abolition of serfdom and he is presented as a cold, calculating and nihilist character.

I think Smerdyakov is Fyodor's bastard and that he might have possibly taken advantage (or even raped) his retarded mother, "stinking Lizaveta".

Great posts Book Portrait. I wondered what Dostoevsky thought about those "modern" reforms, specially since despicable Rakitin vouched for the abolition of serfdom and he is presented as a cold, calculating and nihilist character.

I also agree with Samadrita's post re Smerdyakov. I don't know if he is a Karamazov but it certainly looks like it...

I also agree with Samadrita's post re Smerdyakov. I don't know if he is a Karamazov but it certainly looks like it... Balaam's ass

I had to look up "Balaam's ass" (ever colorful Fyodor Pavlovitch!), which turns out to be another biblical reference:

“No, no,” he said [to Alyosha]. “I'll just make the sign of the cross over you, for now. Sit still. Now we've a treat for you, in your own line, too. It'll make you laugh. Balaam's ass has begun talking to us here—and how he talks! How he talks!”

Balaam's ass, it appeared, was the valet, Smerdyakov. He was a young man of about four and twenty, remarkably unsociable and taciturn. Not that he was shy or bashful. On the contrary, he was conceited and seemed to despise everybody.

Book III. Chapter 6

Balaam, in his coveteousness, continues to press God, and God finally gives him over to his greed and permits him to go but with instructions to say only what he commands. Balaam thus, without being asked again, sets out in the morning with the princes of Moab and God becomes angry that he went, and the Angel of the Lord is sent to prevent him.

At first the angel is seen only by the donkey Balaam is riding, which tries to avoid the otherwise invisible angel. After Balaam starts punishing the donkey for refusing to move, it is miraculously given the power to speak to Balaam, and it complains about Balaam's treatment. At this point, Balaam is allowed to see the angel, who informs him that the donkey is the only reason the angel did not kill Balaam. Balaam immediately repents, but is told to go on.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balaam

Thanks Dolors. I wonder about that too. That's why I'm planning to read a biography of Dostoevsky...

The ending of the chapter on Smerdyakov is rather ominous!

The ending of the chapter on Smerdyakov is rather ominous!There is a remarkable picture by the painter Kramskoy, called “Contemplation.” There is a forest in winter, and on a roadway through the forest, in absolute solitude, stands a peasant in a torn kaftan and bark shoes. He stands, as it were, lost in thought. Yet he is not thinking; he is “contemplating.” If any one touched him he would start and look at one as though awakening and bewildered. It's true he would come to himself immediately; but if he were asked what he had been thinking about, he would remember nothing. Yet probably he has, hidden within himself, the impression which had dominated him during the period of contemplation. Those impressions are dear to him and no doubt he hoards them imperceptibly, and even unconsciously. How and why, of course, he does not know either. He may suddenly, after hoarding impressions for many years, abandon everything and go off to Jerusalem on a pilgrimage for his soul's salvation, or perhaps he will suddenly set fire to his native village, and perhaps do both. There are a good many “contemplatives” among the peasantry. Well, Smerdyakov was probably one of them, and he probably was greedily hoarding up his impressions, hardly knowing why. (III.6)

"The Meditator" by Ivan Kramskoy

I have reached further ahead to some reminiscing about Elder Zosima childhood and about how serfs were bought and sold as slaves, so I think in general Dostoyevsky stands on the liberal bench when it comes to social reforms and on the conservative one when it comes to spirituality.

I have reached further ahead to some reminiscing about Elder Zosima childhood and about how serfs were bought and sold as slaves, so I think in general Dostoyevsky stands on the liberal bench when it comes to social reforms and on the conservative one when it comes to spirituality.What about his portrayal of women? I got three instances in this book : the innocence of the teenager Lise who provides dome much needed comic relief with her earnestness, the haughty and proud Katya treated like a goddess by the men around her, the earthy, alluring Grushenka. In this book they play second fiddle to the brothers K. but I wonder if later in the book they will get equal, indepth treatment? Iam not making right now any comments about their high strung nerves, because this is an affliction that affects both sexes equally in the book.

Ivan Kramskoi

Ivan KramskoiIvan Nikolaevich Kramskoi (June 8 (O.S. May 27), 1837, Ostrogozhsk – April 6 (O.S. March 24), 1887, Saint Petersburg) was a Russian painter and art critic. He was an intellectual leader of the Russian democratic art movement in 1860-1880.

Self-portrait, 1867

Portrait of Kramskoi by Ilya Repin, 1882.

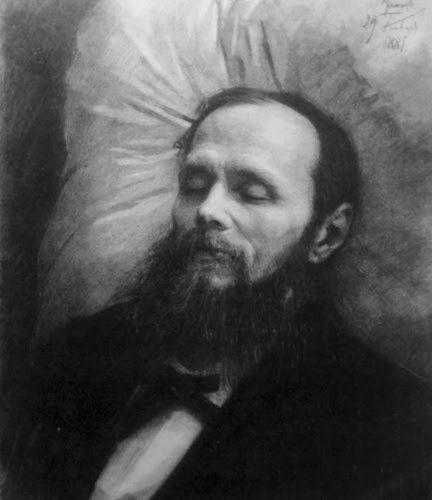

Dostoyevsky on his death bed, drawing by Ivan Kramskoy, 29 January 1881

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivan_Kra...

Collection of Kramskoy paintings at the Tretyakov Gallery:

http://www.tretyakovgallery.ru/en/col...

Moscow merchant and collector of paintings, founder of the Tretyakov Gallery Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov, 1876

Portrait of Vera Tretyakova, 1876

Algernon wrote: "I have reached further ahead to some reminiscing about Elder Zosima childhood and about how serfs were bought and sold as slaves, so I think in general Dostoyevsky stands on the liberal bench when ..."

Algernon wrote: "I have reached further ahead to some reminiscing about Elder Zosima childhood and about how serfs were bought and sold as slaves, so I think in general Dostoyevsky stands on the liberal bench when ..."I'm trying to be good and stick to the schedule (very difficult!) but I started on a biography of Dostoevsky to get a better understanding of his themes and background...

I read that in his youth Dostoevsky loved going to the country house his parents had bought in Darovoïe (French spelling). He was deeply impressed by the goodness in simple good Russian characters: the peasant Mareï (Mark Efremov) and a "village idiot" called Agrafena that he used as inspiration for Lizaveta Smerdyastchaya (Stinking Lizaveta).

Then I showed it [a banknote for five thousand roubles] her in silence, folded it, handed it to her, opened the door into the passage, and, stepping back, made her a deep bow, a most respectful, a most impressive bow, believe me! She shuddered all over, gazed at me for a second, turned horribly pale—white as a sheet, in fact—and all at once, not impetuously but softly, gently, bowed down to my feet—not a boarding-school curtsey, but a Russian bow, with her forehead to the floor. She jumped up and ran away. (III.4)

Then I showed it [a banknote for five thousand roubles] her in silence, folded it, handed it to her, opened the door into the passage, and, stepping back, made her a deep bow, a most respectful, a most impressive bow, believe me! She shuddered all over, gazed at me for a second, turned horribly pale—white as a sheet, in fact—and all at once, not impetuously but softly, gently, bowed down to my feet—not a boarding-school curtsey, but a Russian bow, with her forehead to the floor. She jumped up and ran away. (III.4)Impossible not to notice the parallel between Katerina Ivanovna's Russian bow and Elder Zossima's, both before Dmitri...

Father Zossima moved towards Dmitri and reaching him sank on his knees before him. Alyosha thought that he had fallen from weakness, but this was not so. The elder distinctly and deliberately bowed down at Dmitri's feet till his forehead touched the floor. (II.6)

Fyodor Pavlovitch, agent provocateur extraordinaire, further loosened by some Cognac, talks about Staret Zossima:

Fyodor Pavlovitch, agent provocateur extraordinaire, further loosened by some Cognac, talks about Staret Zossima:“Listen, Alyosha, I was rude to your elder this morning. But I was excited. But there's wit in that elder, don't you think, Ivan?”

“Very likely.”

“There is, there is. Il y a du Piron là-dedans. He's a Jesuit, a Russian one, that is. As he's an honorable person there's a hidden indignation boiling within him at having to pretend and affect holiness.”

“But, of course, he believes in God.”

“Not a bit of it. Didn't you know? Why, he tells every one so, himself. That is, not every one, but all the clever people who come to him. He said straight out to Governor Schultz not long ago: ‘Credo, but I don't know in what.’ ”

“Really?”

“He really did. But I respect him. There's something of Mephistopheles about him, or rather of ‘The hero of our time’ ... Arbenin, or what's his name?... You see, he's a sensualist. He's such a sensualist that I should be afraid for my daughter or my wife if she went to confess to him. (III.8)

Piron

My edition is not annotated but my sleuthing concluded that the Piron in question is Alexis Piron (1689–1773), a French writer famous (at the time?) for his epigrams:

Alexis Piron by Jean-Jacques Caffieri. Dijon, Musée des beaux-arts

Piron is compared to the Elder in The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Pavlovich as a compliment of wit.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexis_P...

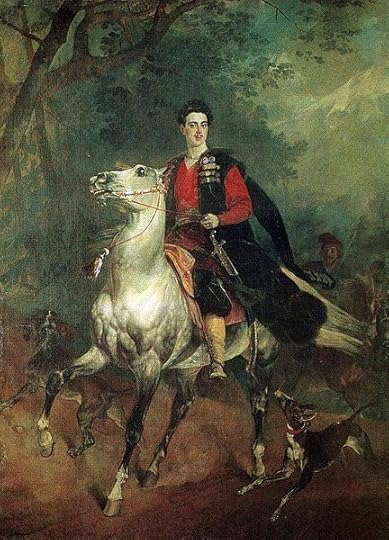

Mikhaïl Lermontov

A Hero of Our Time was written by Mikhaïl Lermontov and features anti-hero Pechorin.

Mikhail Lermontov in 1837

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov (1814–1841), a Russian Romantic writer, poet and painter, sometimes called "the poet of the Caucasus", became the most important Russian poet after Alexander Pushkin's death in 1837. Lermontov is considered the supreme poet of Russian literature alongside Pushkin and the greatest figure in Russian Romanticism. His influence on later Russian literature is still felt in modern times, not only through his poetry, but also through his prose, which founded the tradition of the Russian psychological novel.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mikhail_...

A Hero of Our Time (Russian: Герой нашего времени, Geroy nashevo vremeni) is a novel by Mikhail Lermontov, written in 1839 and revised in 1841. It is an example of the superfluous man novel, noted for its compelling Byronic hero (or anti-hero) Pechorin and for the beautiful descriptions of the Caucasus. There are several English translations, including one by Vladimir Nabokov and Dmitri Nabokov in 1958.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Hero_o...

Demidov

Demidov"He did Demidov, the merchant, out of sixty thousand." (III.8)

The Demidov (Russian: Деми́довы) family, also Demidoff, were an influential Russian merchant, industrialist and noble family, possibly second only to the Tsar himself in wealth during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The family still exists.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demidov

I don't know which Demidov Fyodor is talking about!

Count Nikolai Nikitich Demidov (9 October/November 1773, Chirkovitsy, Saint Petersburg Governorate - 22 April 1828, Florence) was a Russian industrialist, collector and arts patron of the Demidov family.

Count Anatoly (called Anatole) Nikolaievich Demidov, 1st Prince of San Donato (Russian: Анатолий Николаевич Демидов; 5 April OS: 24 March 1813 – 29 April 1870), was a Russian industrialist, diplomat and arts patron of the Demidov family.

[Alyosha] “Brother, let me ask one thing more: has any man a right to look at other men and decide which is worthy to live?”

[Alyosha] “Brother, let me ask one thing more: has any man a right to look at other men and decide which is worthy to live?”[Ivan]“Why bring in the question of worth? The matter is most often decided in men's hearts on other grounds much more natural. And as for rights—who has not the right to wish?”

“Not for another man's death?”

“What even if for another man's death? Why lie to oneself since all men live so and perhaps cannot help living so. Are you referring to what I said just now—that one reptile will devour the other? In that case let me ask you, do you think me like Dmitri capable of shedding Æsop's blood, murdering him, eh?” (III.9)

My sleuthing fails here. What is Ivan referring to when he talks about 'one reptile devouring the other' and 'shedding Aesop's blood'?

Algernon wrote: "So, what's your take on Smerdyakov? is he, or isn't he a Karamazov? based on the information given so far, the narrator makes it possible but not a certainty. I've just read his chapter on faith an..."

Algernon wrote: "So, what's your take on Smerdyakov? is he, or isn't he a Karamazov? based on the information given so far, the narrator makes it possible but not a certainty. I've just read his chapter on faith an..."I am wondering if Fyodor is Ivan's father.

p102 Fyodor is speaking of Sofya, Ivan & Alexei's mother. How he seduced her and kept her "fascinated" with him; the altercation between him and Belyavsky (who courted his wife & made a habit of visiting & slapped Fyodor in his own home...could he be the father?); Sofya called for a duel; Fyodor brought her to the monastery to bring her to her senses...here I thought of Fyodor's assertion that Fr. Zosima was a "sensualist" (p 100...could he be the father of Ivan?).

Alexei reacts just as his mother did. "He's upset about his mother, his mother," he muttered to Ivan.

"'But she was my mother, too, I believe, his mother. Was she not?' said Ivan with uncontrolled anger and contempt. The old man shrank before his flashing eyes. But something very strange had happened, though only for a second; it seemed really to have escaped the old man's mind that Alyosha's mother was actually Ivan's mother too.

'Your mother' he muttered, not understanding. 'What do you mean? What mother are you talking about? Was she?...Why, damn it! of course she was yours too! Damn it! My mind's gone back on me, that never happened before. Excuse me, why, I was thinking, Ivan...He, he he!' He stopped. A broad, drunken, half senseless grin spread over his face." p103

Or is Alexei Fr Zosima's son? The door is open for Alexei's return to the monastery even though it is usually closed at that hour...and Zosima speaks of him on his deathbed. He knows Alexei must go out into the world.

Or was Sofya made to raise another woman's child?

There is so much subterranean in this family. Secrets. Confessionals. Confusion. It's a timeless story. And a page turner!

Did anyone else wonder what this confusion was all about?

TBK, NY Heritage Press

I was struck with Fr Zosima's inability to hear confession on the same day that Alexei served as confessor for his family...Katerina, a clear glimpse of Gruschenka...Smerdyakov speaks...and the pink blush love letter from Lise. We learn that Alexei is a sensualist as well.

I was struck with Fr Zosima's inability to hear confession on the same day that Alexei served as confessor for his family...Katerina, a clear glimpse of Gruschenka...Smerdyakov speaks...and the pink blush love letter from Lise. We learn that Alexei is a sensualist as well."Alyosha read the note in amazement, read it through twice, thought a little, and suddenly laughed a soft, sweet laugh. He started. That laugh seemed to him sinful. But a minute later he laughed again just as softly and happily." p119 He utters a prayer as he peacefully falls asleep.

TBK, NY Heritage Press

Samadrita wrote: "BP, thank you for your posts full of priceless new insights as ever."

Samadrita wrote: "BP, thank you for your posts full of priceless new insights as ever."I echo Samadrita's gratitude. Beautiful to drink in the images...and invaluable to enhance the world of TBK.

Ce Ce wrote: "There is so much subterranean in this family. Secrets. Confessionals. Confusion. It's a timeless story. And a page turner!"

Ce Ce wrote: "There is so much subterranean in this family. Secrets. Confessionals. Confusion. It's a timeless story. And a page turner!"The plot thickens!

I didn't imagine that Fyodor was not the father of Dmitri, Ivan and Alexei. Maybe the background chapters on the family were so dense that the clues escaped me! I'm trying to focus on the political and religious discourses and then I miss all the family drama! I agree that Dostoevsky's writing reads like a page-turner, full of foreshadowing and drama! :)

I've been wondering about the illnesses running in the family. Sofia and Alexei suffer from something mysterious:

In the end this unhappy young woman, kept in terror from her childhood, fell into that kind of nervous disease which is most frequently found in peasant women who are said to be “possessed by devils.” At times after terrible fits of hysterics she even lost her reason. (I.3)

And Smerdyakov has the same illness as Dostoevsky himself:

A week later he had his first attack of the disease to which he was subject all the rest of his life—epilepsy. (...) as soon as he heard of his illness, he showed an active interest in him, sent for a doctor, and tried remedies, but the disease turned out to be incurable. (III.6)

Isn't it strange that Fyodor would suddenly pay attention to Smerdyakov because he is sick?

The reframing of the plot around the Fyodor/Grushenka/Dmitri love triangle struck me:

The reframing of the plot around the Fyodor/Grushenka/Dmitri love triangle struck me:Towering like a mountain above all the rest stood the fatal, insoluble question: How would things end between his father and his brother Dmitri with this terrible woman? (III.10)

Katerina Ivanovna's desire to "save" Dmitri was another surprisingly dramatic scene. I agree with Algernon that we have a cast of rather high strung characters!

these emotional outburst are not limited to Dostroyevsky. Some of my favorite Russian movies express a similar tendency to extrovert manifestation, linking the Slav spirit more to the Latin (Italian, French) exuberance rather than to the reticent British or Nordic cultures.

these emotional outburst are not limited to Dostroyevsky. Some of my favorite Russian movies express a similar tendency to extrovert manifestation, linking the Slav spirit more to the Latin (Italian, French) exuberance rather than to the reticent British or Nordic cultures.

Algernon wrote: "...a similar tendency to extrovert manifestation, linking the Slav spirit more to the Latin (Italia..."

Algernon wrote: "...a similar tendency to extrovert manifestation, linking the Slav spirit more to the Latin (Italia..."I didn't know that. I started reading a short biography of Dostoïevski and he seemed to be a volatile, passionate, extreme character himself!

I enclose an article I found in a Catalan newspaper which refers to the significance of the names in TBK.

It seems that kara means black in tartar language, which might refer to the fateful bleakness of the soul of these brothers. And amazingly, smerdet is a Russian verb which means "stink".

Nothing in this novel is coincidental, I am afraid.

http://www.ara.cat/premium/llegim/fut...

It seems that kara means black in tartar language, which might refer to the fateful bleakness of the soul of these brothers. And amazingly, smerdet is a Russian verb which means "stink".

Nothing in this novel is coincidental, I am afraid.

http://www.ara.cat/premium/llegim/fut...

Book Portrait wrote: "The reframing of the plot around the Fyodor/Grushenka/Dmitri love triangle struck me:

Towering like a mountain above all the rest stood the fatal, insoluble question: How would things end between ..."

That was very shocking for me as well. Women in War & Peace were presented in a much more composed and almost pious fashion. Dostoevky's female characters are volcanoes about to burst. Grusha is a walking temptation, a sort of femme fatale, with impassioned nature and sort of manipulative drive. Katya appears of a more lofty nature but equally exasperating. Liza is conceited and fastidious yet innocent. I am afraid Dostoevsky had his own opinion regarding women and it wasn't precisely unbiased. You know, where there is money and women, sure trouble to come! :)

Towering like a mountain above all the rest stood the fatal, insoluble question: How would things end between ..."

That was very shocking for me as well. Women in War & Peace were presented in a much more composed and almost pious fashion. Dostoevky's female characters are volcanoes about to burst. Grusha is a walking temptation, a sort of femme fatale, with impassioned nature and sort of manipulative drive. Katya appears of a more lofty nature but equally exasperating. Liza is conceited and fastidious yet innocent. I am afraid Dostoevsky had his own opinion regarding women and it wasn't precisely unbiased. You know, where there is money and women, sure trouble to come! :)

Book Portrait wrote: "Ce Ce wrote: "There is so much subterranean in this family. Secrets. Confessionals. Confusion. It's a timeless story. And a page turner!"

Book Portrait wrote: "Ce Ce wrote: "There is so much subterranean in this family. Secrets. Confessionals. Confusion. It's a timeless story. And a page turner!"The plot thickens!

I didn't imagine that Fyodor was not t..."

I returned to Book I and II. Sofya gave birth to Ivan and Alexei. If there is mystery it seems it is Alexei.

Although Alexei's mother died when he was four he remembered her.

"He remembered one still summer evening, an open window, the slanting rays of the setting sun (that he recalled the most vividly of all; in a corner of the room the holy image, before it a lighted lamp, and on her knees before the image his mother, sobbing hysterically with shrieks and moans, snatching him up in both arms, squeezing him close till it hurt, and praying for him to the Mother of God, holding him out in both arms to the Mother's protection...and suddenly a nurse runs in and snatches him from her in terror." p12

Alyosha seeks out is mother's grave. Fyodor has forgotten its location. Grigory leads Alyosha to it; Grigory had arranged for the headstone rather than Fyodor.

It was perhaps a year before he [Alexei] visited the cemetery again. But this little episode was not without its influence upon Fyodor Pavlovich - and a very peculiar one. He suddenly took a thousand roubles to our monastery to pay for requiems for the soul of his wife; but not for the second, Alyosha's mother, the 'possessed woman,' but for the first, Adelaida Ivanovna, who used to thrash him. In the evening of the same day he got drunk and abused the monks to Alyosha." p15

"Perhaps his [Alexei] memories of childhood brought back our monastery, to which his mother may have taken him to mass. Perhaps the slanting sunlight and the holy image to which his poor 'possessed' mother had held him up still acted upon his imagination. Brooding on these things, he may have come to us perhaps only to see whether here he could sacrifice all or only 'two roubles,' and in the monastery he met this elder [Zosima]..." p18

With the arrival of his two brothers, Dmitri & Ivan...he more quickly made friends with his half-brother, Dmitri. After months even though Ivan and Alyosha met frequently they still were not close.

Alyosha was naturally reserved, and he seemed to be expecting something, ashamed of something, while is brother Ivan, though Alyosha noticed at first that he looked long and curiously at him, seemed soon to have left off thinking about him. Alyosha noticed it with some embarrassment. He ascribed his brother's indifference at first to the disparity of their age and education. But he also wondered whether the absence of interest and sympathy in Ivan might be due to some other cause entirely unknown to him." p21

TBK, NY Heritage Press

Book Portrait wrote: "The reframing of the plot around the Fyodor/Grushenka/Dmitri love triangle struck me:

Book Portrait wrote: "The reframing of the plot around the Fyodor/Grushenka/Dmitri love triangle struck me:Towering like a mountain above all the rest stood the fatal, insoluble question: How would things end between ..."

The triangle of Dmitri/Katerina/Ivan

The triangle of Katerina/Dmitri/Grushenka (it was shocking when Grushenka walked out from behind the curtain at Katerina's to play out a near seduction of Katerina)

The triangle of Fyodor/Alexei/Zosima

Dolors wrote: "I enclose an article I found in a Catalan newspaper which refers to the significance of the names in TBK.

Dolors wrote: "I enclose an article I found in a Catalan newspaper which refers to the significance of the names in TBK.It seems that kara means black in tartar language, which might refer to the fateful bleakn..."

Yes, definitely, the names are significant.

The Kara=black, is one theory another is that the root of kara gives words for punishment and to punish in Russian and the mazov suggests something like to smear or to paint, so the name might mean something along the lines of punishment-smeared!

Dostoevsky giving his own name Fyodor to the Karamozov patriarch is interesting.

Ivan is the classic Russian man's name, Alexei the man of God well, have a look:

http://orthodoxwiki.org/Alexios_the_M...

Dmitri is a russification of Demetrius which in turn is the male version of the goddess Demeter (fertility, nature etc)

Dolors wrote: "I enclose an article I found in a Catalan newspaper which refers to the significance of the names in TBK.

Dolors wrote: "I enclose an article I found in a Catalan newspaper which refers to the significance of the names in TBK.It seems that kara means black in tartar language, which might refer to the fateful bleakn..."

I think the article is premium content. There's only the first few lines. :(

I didn't know "kara" means black! Isn't it a terrible for Smerdyakov that his name is an insult? This is the other character (besides Ivan) that I'd worry about. Smerdyakov has to endure some treatment by Fyodor! I would be surprised if he didn't harbor plans to exact some revenge... In fact it feels as if all four sons would have a motive to want to harm Fyodor. Why is the self-professed buffon allowing them all in his house?

Jan-Maat wrote: "Dolors wrote: "I enclose an article I found in a Catalan newspaper which refers to the significance of the names in TBK.

Jan-Maat wrote: "Dolors wrote: "I enclose an article I found in a Catalan newspaper which refers to the significance of the names in TBK.It seems that kara means black in tartar language, which might refer to the..."

In greek, Alex means "help" and "protection", like in Alex-andros

Ce Ce wrote: "I returned to Book I and II. Sofya gave birth to Ivan and Alexei. If there is mystery it seems it is Alexei..."

Ce Ce wrote: "I returned to Book I and II. Sofya gave birth to Ivan and Alexei. If there is mystery it seems it is Alexei..."So much violence mixed in with love and spirituality in Sofia 's death scene... The fact that all three mothers of the four sons are dead heightens the possible need for some sort of revenge against Fyodor...

I was surprised that Ivan and Alyosha didn't get along better when they reunited...

Jan-Maat wrote: "Yes, definitely, the names are significant.

Jan-Maat wrote: "Yes, definitely, the names are significant.The Kara=black, is one theory another is that the root of kara gives words for punishment and to punish in Russian and the mazov s.."

Very interesting! I was also surprised that Dostoevsky gave his first name to the character who is the most evil one, basically the apparent villain of the story. And he gives his epilepsy to Smerdyakov...

I really like that Alexios the Man of God icon for Alexei:

Yann wrote: "In greek, Alex means "help" and "protection", like in Alex-andros "

Yann wrote: "In greek, Alex means "help" and "protection", like in Alex-andros "And andros means "man"? So Alexei would the protector/helper? Things might not turn out too badly for him... but only after a lot of suffering I imagine... {please don't spoiler me! :)}

Dolors wrote: "Book Portrait wrote: "The reframing of the plot around the Fyodor/Grushenka/Dmitri love triangle struck me:

Towering like a mountain above all the rest stood the fatal, insoluble question: How wou..."

Trouble trouble indeed. And it act as a reminder that the book so far is primarily about Fathers and Sons rather than Mothers and Daughters.

Great post about the significance of names too Dolors. As for Smerdyakov being a Karamazov, I'll have my mild doubts till I come across some closure w/r/t that because I can't ignore Aloyasha's words about his father: Your heart is better than your head.

And this thread full of priceless comments. Thank you all.

Towering like a mountain above all the rest stood the fatal, insoluble question: How wou..."

Trouble trouble indeed. And it act as a reminder that the book so far is primarily about Fathers and Sons rather than Mothers and Daughters.

Great post about the significance of names too Dolors. As for Smerdyakov being a Karamazov, I'll have my mild doubts till I come across some closure w/r/t that because I can't ignore Aloyasha's words about his father: Your heart is better than your head.

And this thread full of priceless comments. Thank you all.

Smerdyakov, "the stinking one", inheriting the stink of his mother, living in proximity to the "stinking" little local stream.

Smerdyakov, "the stinking one", inheriting the stink of his mother, living in proximity to the "stinking" little local stream.Bad smells. Enlightened people make a thing of "tolerating" them- in fact, nothing can be done at all about a bad smell, so there is no special virtue in toleration. One reacts with an expression of disgust, another bears the offense impassively...

Smerdyakov bears this onus, like a cross. He was born under its sign.

Bastardy.

All of this in his relation to his papa, in formal terms his master, his employer, his BENEFACTOR.

And the readership of the world knows him as a murderer, similar in soul to Judas... "A lacky soul"

O gentle reader, will you damn him?

-Sam

Dostoevsky never attached any importance whatsoever to the mystery aspect of murder. His Russian worldview valued the moral courage of candor in deed.

Dostoevsky never attached any importance whatsoever to the mystery aspect of murder. His Russian worldview valued the moral courage of candor in deed.But as to Smerdyakov, he's very intelligent, with the misfortune of a low caste, relegated to entertainment for the masters, who like to play him against Grigory.

My 3rd, and last, commentary on Smerdyakov.

My 3rd, and last, commentary on Smerdyakov.He is not introduced, along with his mother, until Sensualists.

His sensualism is in relation to Alyosha as the closest to him in age among the boys. In his uniquely oppressed and burdened soul, his development bears the shock of recognition.

The torture and killing of animals, together with ritualistic play- morbidity. I believe this was Dostoevsky's indication of satanic practice- "partaking of satan's pride" as fr Zosima put it.

Returning from Moscow in a greatly aged, desiccated condition, together with great attention to personal style- shining his boots like mirrors... This indicates advanced heroin use.

His musical ability- singing in falsetto, with guitar, an emotional and melancholy register- certainly not without talent.

His disinterest in the opposite sex.

We have here the profile of a member of any given witch house band.

By this Dostoevsky was saying something about the state of the arts in the West, via Smerdyakov as a Russian touchstone for Western influences... And wanting the reader to compare all this with Alyosha's writings of remembered talks and homilies of his dearly departed in god elder Zosima.

Dostoevsky is telling the reader something about life and art- the immortal life of classic art as opposed to the fashionable oblivion of what we know as hipster art.

Thus Dostoevsky leads us down the novel's path, by critique and example, to belief in god and immortal life- the classic work of genius and it's abiding contribution to world civilization- a goal that has been abandoned- even with a curse, ever since Vincent Van Gogh.

Smerdyakov, subject to the same corrupting forces as van Gogh, was destroyed... But van Gogh was able to achieve greatness in spite of all because of his own individual and idiosyncratic Alyosha-like beliefs.

Books mentioned in this topic

Dostoïevski (other topics)A Hero of Our Time (other topics)